1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, will releasing the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles to be reviewed. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

-oOo-

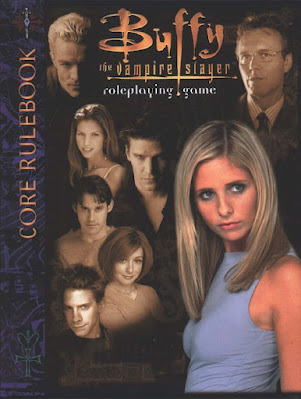

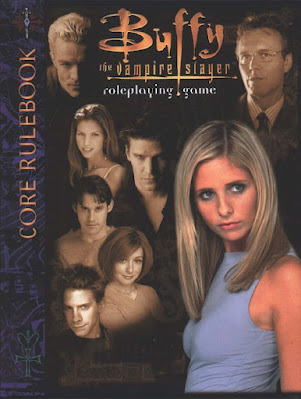

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game was published in 2002. Published by

Eden Studios, Inc., best known for the definitive roleplaying game of zombie action and survival,

All Flesh Must be Eaten, it is an adaptation of the cult television series which ran between 1997 and 2003. Set in the California town of Sunnydale, it depicts the lives, loves, and conflicts of a group of friends who fight vampires. Or rather a group of friends who help out Buffy Summers, a girl in high school who becomes the ‘Slayer’, or Vampire Slayer, chosen and empowered fate to battle against vampires, demons and other forces of darkness. Despite wanting to live a normal life, Buffy is constantly stalked and attacked by vampires, whilst other powers—known in the series as ‘Big Bads’—plot against her, all attracted to Sunnydale because it sits atop a Hellmouth. As a Slayer, Buffy is aided by a Watcher, who guides, teaches and trains her, and helped by her friends, who are collectively known as the ‘Scooby Gang’ in reference to the long running cartoon. As much as the term ‘Scooby Gang’ is appropriate,

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is very much a more modern approach to the idea of monster hunting, reflected in the look and tone of the series, dealing up three parts action-horror, irony, and feeling combined with strong positive roles and depictions of its characters, especially the female ones.

The

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is designed to be played in two ways. First, it can be played using the cast from the television series, and to that end, character sheets are provided for the series’ protagonists up until season five. This is perfect for one shots or convention games, and like many licensed roleplaying games is an attractive means to introduce fans of a particular intellectual property to the concept of roleplaying. However, the second way is playing using characters of the players’ own creation, as is standard in most roleplaying games. That comes up against an issue. Which is, who plays the Slayer? There is only meant to be one Slayer, although as the Buffyverse expands, this is not the case. This ranges from the initially canonical there can only be the one Slayer or one and a replacement Slayer to a handful of Slayers and male or canine Slayers! It all depends on how far the gaming group wants to diverge from the television series. In part, who gets to roleplay the Slayer is important because just as in the television series, the Slayer in the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is very powerful, the other roles less so (although over time they can grow into their own).

A character in the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is defined by Attributes, Qualities and Drawback, and Skills, as well as Drama Points. The six attributes are Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Intelligence, Perception, and Willpower. Qualities are advantages and Drawbacks are disadvantages. Attributes typically range between one and five, but can be higher depending on character type and Qualities selected. Skills range between zero and ten in value. Character creation begins with selecting a Character Type, each of which defines the number of points which can be assigned to Attributes, Qualities and Drawback, and Skills. Three are given—White Hat, Hero, and Experienced Hero. White Hats are ordinary folk, like Xander Harris or Willow Rosenberg, specialised in particular skills, such as magic, knowledge, or the occult, and who on their own, have difficulty facing a vampire. Heroes are stronger and faster, able to face a vampire one-on-one and destroy it, such as Buffy or Riley of the Initiative. Experienced Heroes are even stronger and represent Buffy later in the television series, but are not recommended for starting play. Although there is no Character Type for it, some of the Scooby Gang from the series are designed as Experienced White Hats. Once a Character Type is chosen, it is a matter of assigning the points and designing the character, often building out from a Quality based on the player’s concept, for example, a Watcher character requires the Watcher Quality or a warlock or wizard would need the Sorcery Quality. The character creation is not difficult and is clearly explained, plus the book includes not only twelve starting Player Characters or archetypes as examples, including New Slayer, Watcher, Former Vampire Groupie, Psychic, Beginner Witch, and more, but also character sheets for all of the major cast and members of the Scooby Gang, including Spike and Angel, with adjustments season by season, from seasons one to five.

Theodore Buckner is from Philadelphia, but has been sent to Sunnydale to live with his grandmother, whilst his parents are working abroad. He has learned to be self-sufficient and strong willed because he has been bullied at school ever since he can remember, whilst at home, he has learned to keep an eye on his grandmother and her medications, as she is often housebound. He loves reading and playing

Dungeons & Dragons, and was fascinated by some books he found in his grandmother’s library which revealed that magic is real. Now he can play his favourite character Class, a Warlock!

NAME: Theodore BucknerCHARACTER TYPE: White HatCHARACTER CONCEPT: Gamer turned WarlockLife Points: 28Drama Points: 20ATTRIBUTESStrength 1 Dexterity 2 Constitution 2 Intelligence 4* Perception 3 Willpower 5*(1 Level from Nerd Quality)

QUALITIES (+8 from Drawbacks)Good Luck-2 (+2), Hard to Kill-2 (+2), Nerd (+3), Occult Library (+1), Sorcery-2 (+10)

DRAWBACKSUnattractive (-1), Clown (-1), Misfit (-2), Dependent (Grandmother) (-2), Teenager (-2)

SKILLSAcrobatics 0 Art 0 Computers 2 Crime 0 Doctor 1 Driving 0 Getting Medieval 0 Gun Fu 0 Influence 1 Knowledge 4 Kung Fu 1 Languages 1 Mr. Fix-It 0 Notice 0 Occultism 1 Science 3 Sports 0 Wild Card (

Dungeons & Dragons) 2Manoeuvres / Bonus / Base / Damage NotesDodge / 2 / — / Defense actionMagic / 8 / Varies By spellStake / 2 / 0 / Slash/stab (Through the Heart) 0 2 ×5 vs. vampiresTelekinesis / 7 / 2 × Success Levels Bash or Slash/stab

Mechanically, the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game uses the

Unisystem mechanics first seen in

All Flesh Must Be Eaten. Or rather, it uses a stripped-down version called

Cinematic Unisystem designed for faster, more dynamic play, which would go on to be used in several of Eden Studios, Inc.’s other roleplaying games, including the

Angel Roleplaying Game,

Army of Darkness Roleplaying Game, and

Ghosts of Albion Roleplaying Game. To have his character undertake an action, a player rolls a ten-sided die, and adds either the appropriate attribute and skill or double the attribute if no skill is involved, plus any bonuses from appropriate Qualities. The roll itself can be modified for difficulty and other factors, but the aim is always to roll nine or more. A typical White Hat will be adding five or six to this roll at most, whilst a Slayer, even a starting Slayer, will be adding twelve in combat. The aim here is not just to succeed, but to roll multiple Success Levels, one for every two points above nine. This determines how well the Player Character performed or how much of a task he completed, or how much extra damage he inflicted in combat. Besides standard actions, the rules cover research, fear checks or ‘getting the wiggins’, but the main focus is upon combat.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is an action-horror television series and the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is an action action-horror roleplaying game, and both cinematic in style. In fact, it is also a martial arts action-horror roleplaying game, because the Slayer in particular, will be engaging in jump kicks and spin kicks and sweep kicks, slam tackles, and more as well as decapitations, feints, dodges, wrestling holds, and so on, not forgetting of course, Through the Heart stake action. Gun combat is covered in the rules, but

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is all about the cinematic, martial arts action rather than shooting things—which would attract the police—and so all of those martial arts manoeuvres are built into the roleplaying game, and whilst the players should be noting them down on their character sheet, there is very handy list and their effects in the back of the book. Success Levels count for a lot in the game as the greater the number of Success Levels a Player Character can generate, the more damage he can inflict, and in some cases, the greater the multiplier to determine the damage inflicted. Most notably, the damage done when attempting to stake a vampire through the heart. This is not instant in the game, it is possible to miss the heart, but if the damage exceeds the target vampire’s Life points, then he is done and dusted. This modelled by applying a multiplier of five to the Success Levels to determine the damage done.

With Qualities such as Slayer and Hard to Kill, as well as high physical attributes and combat skills, the Slayer will find herself rolling with the punches, spin kicking vamps, and dusting them to death (again) with alacrity. Not so, the White Hats. Even the weakest, newest of vampires represents a severe challenge for them, and unless they get lucky, they are toast. Fortunately, they have two means of withstanding vampire attacks. First is teamwork, hopefully work together until the Slayer can land the final stake. The second is Drama Points. Drama Points are a balancing factor in the game. White Hats have double the number that Heroes have—and they need them.

There are five uses of Drama Points—‘Heroic Feat’, ‘I Think I’m Okay’, ‘Righteous Fury’, ‘Plot Twists’, and ‘Back from the Dead’. ‘Heroic Feat’ grants a +10 bonus to a single roll, in and out of combat; ‘I Think I’m Okay’ halves all of the damage that the Player Character has suffered so far; ‘Righteous Fury’ gives +5 to all combat rolls for a whole fight; ‘Plot Twists’ enables the player to add or change an aspect the game; and ‘Back from the Dead’ does exactly that for characters who are dead. However, once spent, Drama Points are used and cannot be regenerated. Instead, they have to be earned or purchased. The latter uses Experience Points and costs more for a Hero than a White Hat—again enforcing the one advantage that the White Hat has over a Hero. They are earned for coming up with funny, quotable lines in game, for committing heroic acts, and for when something bad happens to a character.

Magic, as per the television series is primarily used as a narrative device, requiring research to determine if a spell is available in the Player Character’s Occult Library, which only contains a limited number of spells until more volumes are found. The rules allow for some magic spells to be cast in combat, but emphasises rituals rather than quickly unleashed bolts of fire. A handful of spells is listed, but the likelihood is that the Player Character Witch or Warlock will be building spells from scratch, which the rules do focus on. To cast a spell, the Witch or Warlock’s player adds the character’s Willpower, Occultism, and Sorcery to a roll of the die. It is not enough to succeed, but the Success Levels rolled must equal the Power Level of the spell, for example, the Power Level of seven for

Amy’s ‘Rat-Ification’ Spell. If the number of Success Levels is lower than the Power Level, then there are side effects, and there is a table to determine what they are, which allows for plenty of input from the Director. Lastly, magic using characters can use telekinesis for various things, including attacks. The magic system is fairly short, and would be greatly expanded upon with

The Magic Box supplement. For the Player Character Witch or Warlock this supplement is a must, since the core rules really only explore the subject so far… Consequently, this is perhaps where the B

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is at its weakest.

For the Director—as the Game Master is known in the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game—there background on Sunnydale and stats and backgrounds for all of its important NPCs. Monsters and vampires have their own chapter too, primarily focusing on vampires and demons, and as well as the means for the Director to create her own, there are stats for just every monster, vampire, Big Bad, and more included in the book. For the most part, the NPC and monster stats are kept simple, with just three attributes— Muscle, Combat, and Brains, along with simplified abilities intended to make them easier to use in play. In addition, there is advice for the Director on setting up and running a series, in particular, how to start with the Big Bad and work out from there, defining his aims and resources, when he will appear in episodes, working out the plot and adding subplots, and then doing the same with episodes. Particular attention is paid to special episodes—season premieres and season finales, all of which should help the Director build a season which emulates the format and structure of the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game. It is a very well-done piece of analysis rewritten as advice for the Director.

Then the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game puts all of that advice into practice with the scenario, ‘Sweeps Week’. Set in Sunnydale with the Player Characters in Sunnydale, it presents an intriguing pop culture mystery with more than a few red herrings and plenty of action. It is a great starting adventure which comes with plenty of tips for the Director, gets the tone of the television series rights, and showcases how beginning adventures in rulebooks do not have to be an afterthought. A good adventure in the core showcases the types of adventures it is intended to handle and what the Player Characters should be doing in play, and ‘Sweeps Night’ does that very well.

Physically, the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is incredibly well presented. It is liberally illustrated with photographs from the series, and where artwork is used, such as in the sample archetypes, that too is very nicely done. The book uses the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer trade dress very well and similarly, the book is incredibly well written, designed for both the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer fan new to roleplaying and the roleplayer new to

Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The opening fiction sets the scene, as does the overviews of the first five seasons of the television series, with explanations of what the book is in between. Whilst there is no example of character generation, there are numerous examples of Player Characters, both members of the cast and starting archetype characters. The latter are accompanied by backgrounds and roleplaying notes as well, all ready to hand out to the players. Interspersed throughout are quote after quote from the series, further enforcing the feel of the series in the roleplaying game, backed up by the glossary of ‘Buffy Speak’ at the back of the book. This is followed by glossary of gaming terms, reference tables, and an index, and there plenty of examples of the rules in play throughout too, including an extended example of combat, something that modern roleplaying games all too often omit.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer was a very geeky television series, a combination of action, horror, comedy, and drama, all served up with a very knowing sense of irony. The the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game captures that and not only puts it on the page, but makes it playable.

The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game, published by Decipher, Inc. also in 2002, would go on to win the

Origins Award for Best Roleplaying Game 2002. As a licensed adaptation of its source material, the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is undeniably the superior design and implementation, showing a wonderfully enjoyable and insightful understanding of the source material. Under any circumstances, the

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Roleplaying Game is one of the outstanding roleplaying adaptations, which if there was a list of top licensed roleplaying games, deserves to go in the top five, if not the top three.

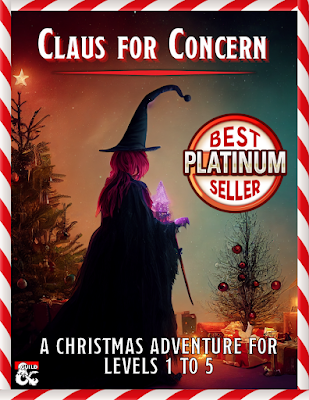

Almost like films on the Hallmark channel, Christmas brings with it festively-themed scenarios for Dungeons & Dragons. Typically, they involve Santa Claus getting kidnapped or Santa’s grotto or toy workshop at the North Pole being invaded, and the Player Characters having either to rescue him or deliver presents down all of the chimneys in the world and into children’s stockings everywhere. And the whole affair is wrapped in a kitsch swathe of red, green, and white, whether that is wrapping paper, bows, candy cane sweets, baubles, and whatnot, all of which is being invaded by someone who is monstrously grey and wants to spread misery rather than joy, but who only needs to be shown some love and the error of their ways so that they once again enjoy the bonhomie of Christmas. It is both a well-worn cliché and extremely American. Claus for Concern: A Holiday One-Shot for Christmas is no different. Published on the Dungeon Masters Guild, it is a scenario for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition.

Almost like films on the Hallmark channel, Christmas brings with it festively-themed scenarios for Dungeons & Dragons. Typically, they involve Santa Claus getting kidnapped or Santa’s grotto or toy workshop at the North Pole being invaded, and the Player Characters having either to rescue him or deliver presents down all of the chimneys in the world and into children’s stockings everywhere. And the whole affair is wrapped in a kitsch swathe of red, green, and white, whether that is wrapping paper, bows, candy cane sweets, baubles, and whatnot, all of which is being invaded by someone who is monstrously grey and wants to spread misery rather than joy, but who only needs to be shown some love and the error of their ways so that they once again enjoy the bonhomie of Christmas. It is both a well-worn cliché and extremely American. Claus for Concern: A Holiday One-Shot for Christmas is no different. Published on the Dungeon Masters Guild, it is a scenario for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition.