Across the patchwork of city-states, dukedoms, baronies, and petty kingdoms that make up Brancalonia, great generals ride at the head of their armies into war. Elsewhere honourable knights face down ferocious dragons, save the princess, and win both her hand and her father’s seat. Mighty wizards study the greatest of magical tomes revealing fantastic secrets and learn spells capable of warping reality itself. Brave adventurers and treasure-seekers delve into the ruins and underground complexes of the ancient Kingdom of Plutonia, the collapse of which led to the Thousand Years’ War, returning with treasures and secrets of the long past. The Kingdom of Brancalonia is a land of opportunity and adventure—but fighting wars, killing dragons, saving princesses, studying hard, and exploring deep underground, they are not your adventures, and they are not your opportunities. You might see that brave knight, mighty army, or learned wizard ride by as you step out of the House of Mother Josephine’s Rest into the sunshine, a plate of ‘Extreme Unction’ macaroni* in one hand and a cup of Troglodyte of Panduria** in the other, before you go back inside and return to the revelry you were engaged in before you got distracted by the noise outside. Perhaps to throw your wine and breakfast aside and leap into the brawl which has broken out in the meantime. After all, it is a matter of principle to support the members of your fellow brotherhood. Or you want to discuss your next job, for the silver is running short, your gear is looking shoddy, and who knows when the next bowl of zuppa di topi Bianchi or bottle of Fil de Ferro will come along? You are a knave, a ne’er do well, a scoundrel, a swindler, or a layabout—if not all four, with a misdeed or misdemeanour to your name or two (or three or…) and minor bounty (or two) on your head. You are not a villain though, but just someone from the dregs of society who knows that life is cheap and anything but fair, and so you are going to make the best of it. Just like the fellow members of your brotherhood.

*Consume with care. Known to cause fits of tears and heart-attacks.

**One of the finest wines ever to come out of Ausonia. This is not a good vintage, but it is wine.

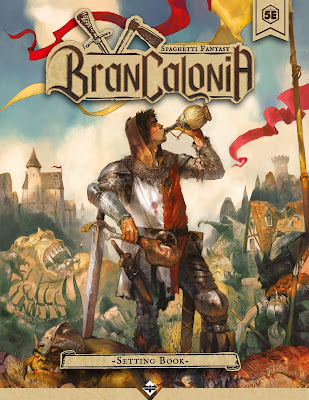

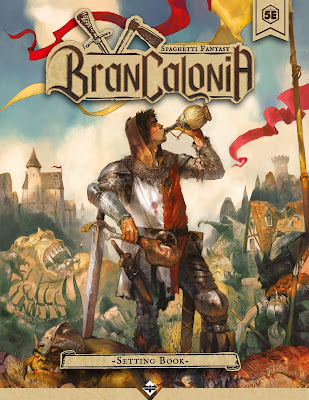

This is the world of Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy, a bawdy, sun-drenched, low fantasy campaign setting for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, inspired by Italian tradition, folklore, history, landscapes, literature, and pop culture. Published by Acheron Books following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it is set in a ‘back-to-front’ version of Medieval Italy—even the gorgeous map is flipped from left to right—in which low life heroes, the Player Characters, form Bands and hopefully get hired by hopefully rich merchants, petty nobles, and desperate warlords to undertake the odd job or two, typically illicit, dangerous, and deniable. That is when they are not concocting their own schemes and running into curses, demons, witches, and angry, abandoned spouses. To a wider audience, the most well-known for Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy will be the films Ladyhawke, Flesh + Blood, and The Princess Bride, along with Carl Collodi’s Pinnochio, but the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book numerous others. All of which are likely to be less familiar to a wider audience. And that is a bit a problem because not all of the inspiration is easily available. However, if instead you think of Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy as being distinctly European fantasy—so there is definitely going to be mud and worse underfoot, not unlike Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, but with better weather, better cooking, and definitely better wine, and then directed by Sergio Leone (with Terry Gilliam as second unit director), then you have the feel of the setting.

The Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book, which won the Gold Ennie for Best Electronic Book in 2021 (plus Silver Awards for Product of the Year, Best Writing, and Best Setting) keeps its fantasy low in a number of ways. First, Player Characters can only advance as high as Sixth Level. Second, whilst it provides five new Races, it does not provide any new Classes. Instead, it gives twelve new Subclasses, one each for the twelve Classes in the Player’s Handbook, along with new Feats and Backgrounds. Third, it gives rules for brawling, intentionally non-lethal combat, which typically takes place in a tavern or other dive before the Player Characters scarper after being accused of a Breach of the Peace and another bounty put on their heads. Fourth, their arms, armour, and other equipment is likely to be shoddy, poorly maintained, and will probably fall apart at the least opportune moment. It eschews the use of Alignment, and even if used, discourages any Player Character choosing to be evil, as Knaves are rogues rather than villains. The setting for the most part is humancentric and does not include the traditional Races of Dungeons & Dragons, although they are not unknown.

Besides Humans, the five new Races in the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book are the Gifted, the Malebranches, the Marionettes, the Morgants, and the Sylvans. The Gifted are Humans who know a little bit more magic; Malebranche are Devils who proclaimed the Great Refusal and climbed out of the Inferno, typically via the Eternal Gate which stands in the great chasm into which Plutonia fell and now stands, and who still have diabolic features such as Hellwings and the Hellvoice; Marionettes are animated puppets, often in the form of Pinnochio or the Paladin-like Pupo, who can remove and use their limbs in a brawl; Morgants are tall ‘demi-giants’ with great strength and appetite, known as fearless brawlers and champions often stationed at the vanguard of an army; and Sylvans are rustics at home in the forest. In addition, each Race has its brawl feature which gives it an advantage in nonlethal fight. The first of the twelve new Classes in the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book is the Pagan, a Barbarian subclass, inhabitants of the Pagan Plain who favour speed, anger, and violence; the Harlequin is a Bard as street entertainer; the Miraculist is a Cleric who follows the calendar and favours the saints, and knows several defensive or helpful spells; the Benadante is a Druid as a forest sorcerer capable of interacting with and defending against the undead; the Swordfighter is a duelling archetype for the Fighter; the Friar is a Monk turned religious brawler; the Knight-Errant is the Paladin as rambling protector of the good, and likely the most courageous of any Knave; the Matador, a Ranger who hunts beasts and monsters in the wilds and fights them in the arena; the Brigand is a Rogue who steals from the wealthy and redistributes what he steals, and can always catch his targets by surprise; the Superstician is a very lucky Sorcerer who can also cast protective rituals; the Jinx is a Warlock who has the districting power of the Evil Eye and even cause misfortune; and the Guiscard is a Wizard who specialises in tomb robbing and treasure hunting.

To these Subclasses are added backgrounds such as the Brawler, the Finagler, and the Fugitive, as well as Feats like Ancient Culinary Art, Apothecary, Jibber-Jabber, and Peasant Soul. There are rules too for advancing beyond Sixth Level, but each new Level only grants an Emeriticence, such as Professional Brawler or Blessed Luck. In addition to creating their Player Characters, they come together to create their Bounty Brothers’ den, a comfortable place where they can rest up and hide. It might be an abandoned farmhouse occupied by brigands, matadors, and smugglers, or a tower in plain sight inhabited by knights-errant, swordsmen, and mercenaries, but all begin with one and can be improved with further Grand Luxuries such as Black Market or a Cantina. This though takes gold and Knaves typically only have silver, so there is a community improvement element to play as the Knaves pool their funds. The Den is also where they ‘Rollick’ and rest—the long rest in Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book is seven days long, too long to take place during actual play—and perhaps improve their Den, reflect on the Job just done (and note any misdeeds and misdemeanours that lead to further bounties being placed on their heads), and plan for the next Job. This will probably result in some kind of hazard as a result of their past activities, and it can be partially offset by going into hiding for a while. And Knaves being who they are, can also engage in Revelry, a few days of good food, good wine, and good company, and so fritter away some of what they just earned…

Other activities the Knaves can engage in are brawls and dive games. Brawls are not like combat in that Hit Points are not lost. Instead, a Brawl attack inflicts Whacks, most Knaves being able to suffer five of them before being knocked unconscious. Brawlers can pick up props, essentially the things around them, and attack with them or use them to defend themselves with. These are divided between common props—pots, dishes, bottles, stools, and so on, and epic props—tables, barrels, chandeliers, suits of armour, and more. In general, a prop has a beneficial effect like gaining a bonus attack or increasing a Knave’s Armour Class, rather than increasing the whacks inflicted. Knaves also have Moves, which are divided into General Moves, Magic Moves, Class Brawl Features, and so. There are Stray Dangers, like ‘Rain of Stools’ or ‘It’s Raining ham’ which the Condottiero—as the Game Master is known in the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book is called—can add to a brawl. The brawl rules are definitely designed to be cinematic in style and add a sense of action and comedy to play.

In addition to brawling in Dives, a Knave likes to play games and gamble—though that is illegal in the Bounty Kingdom. The Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book includes several different Dive games. These include the card game, Poppycock; Barrel Beating, a combined drinking-barrel smashing game in which the winner smashes the barrel and wins the wagers inside; Brancalonian Buffet, an eating contest. There are also rules for shoddy equipment, counterfeiting, equipment for the setting, like the Scudetto, a medium shield which bears the emblem of a city and is thus a symbol of pride for followers of the local Draconian Football Team, concoctions—tonics and the like for what ails you, and even some magical junk. Lastly, there is memorabilia, items of no ecumenic value, but perhaps personal value to their owning Knaves. A Knave begins play with one, but this is not obvious until much later in the book.

For the Game Master—or Condottiero—there is good advice on running Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy. This is to keep the tone light-hearted, magic low, make the game one of tragicomedy and even ‘Grand Guignolesque’, so there is room here for horror too. There is in effect no budget for special effects, or little else, so a game of Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy should be like a film done on the cheap—recycling character actors and redressing extras, natural backdrops and ruins, and so on. Plus, the brawls of ‘brawly’ fantasy to cut down on the bloodshed, but keep up the tension. There is advice as to what to avoid in play—unnecessary violence, sexual themes—though nature of Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy does skirt the issue, and of course, any bigotry. This is the equivalent to safety tools. Plus, there is advice on handling bounties and the law, creating adventures, dives, random roads which may or may go somewhere, and more. There is also a good overall guide to the Bounty Kingdom, its history, its various regions, and even the kingdoms beyond its borders. Each is given a couple of pages, but each includes suggestions as to the types of Jobs that the Knaves might undertake there, and overall, there is just about enough to make each region different and provide the Condottiero with further inspiration.

Penultimately, Condottiero is given a six-part campaign, ‘In Search of Quatrins’ to run. It begins with ‘Little People of the Grand Mount’ and ‘Rugantino: Tales of Love and the Knife’, both of which are for First Level Player Characters, but the first is specifically written as an introductory adventure, one that younger players can roleplay, but also sets up the rest of the scenarios. To this end the Knaves are offered an easy job and the chance to join a company by Roughger of Punchrabbit. The Jobs include treasure hunts, monster hunts, missing marionettes, and more. All together ‘In Search of Quatrins’ should provide a group with several sessions’ worth of play and give them a thorough taste of life in the Bounty Kingdom. They do need some development in places, but the Condottiero should be able to do that as part of preparation. Lastly, Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book includes a bestiary of new monsters and a section of ready to use NPCs.

Physically, the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book looks to be superbly presented, with really good artwork and excellent maps. However, it is a translation from Italian and the localisation and editing is not as good as it could have been. In addition, the index is anaemic, so finding anything in the book will be a challenge. The book could also have been done with a step-by-step guide to creating Player Characters for the setting, as there are several aspects of the process which do not appear until much later in the book. Similarly, a glossary would have been incredibly useful.

Ultimately, whether or not you like the Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book will depend on your feelings towards Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. The new rules presented here do add to Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, but at the same time, they add and enforce the setting and genre of Brancalonia—the brawling, the shoddy equipment, and much, much more. Whether you like it or not, the Bounty Kingdoms setting of Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy jumps from every page into uproarious, tankard banging, wine quaffing, lustily voiced song and then at the end of the night, down in the cups mutterings, before another job presents itself the next day even as you are trying to get over a hangover. Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book presents a delightfully different take upon fantasy, for which even if you do not know the inspiration, the book is inspiring in itself, and you should be creating a cast list (for which Oliver Reed should be your number one choice) even as you read the book and prepare your first adventure. Once you have finished reading Brancalonia – Spaghetti Fantasy Setting Book and prepared your first adventure, you should be ready to bring an inglorious fantasy to the table.

Okay. Remember back in 2017 and that weird thing when colouring books were popular once again. Not just for children, but for adults. Walk into any bookshop and you could find a colouring book on any subject or for any intellectual property you care to name, from the Harry Potter Colouring Book, the Vogue Colouring Book, and The Kew Gardens Exotic Plants Colouring Book to the Lonely Planet Ultimate Travelist Colouring Book, the Day of the Dead Colouring Book, and the Escape to Shakespeare’s World: A Colouring Book Adventure. I gave them as presents, but in all honesty, I had and have no interest in colouring books. Except that Chaosium, Inc. published a colouring book, one inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft. It being from Chaosium, Inc. and it being inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft piqued my interest enough to want to review it, but the main reason to do so was to see if I could review an actual colouring book. Well, I could, and the result was a review of Call of Cthulhu – The Coloring Book: 28 Eldritch Scenes of Lovecraftian for you to Color. However, it turns out it was not the only Lovecraft-inspired colouring book.

Okay. Remember back in 2017 and that weird thing when colouring books were popular once again. Not just for children, but for adults. Walk into any bookshop and you could find a colouring book on any subject or for any intellectual property you care to name, from the Harry Potter Colouring Book, the Vogue Colouring Book, and The Kew Gardens Exotic Plants Colouring Book to the Lonely Planet Ultimate Travelist Colouring Book, the Day of the Dead Colouring Book, and the Escape to Shakespeare’s World: A Colouring Book Adventure. I gave them as presents, but in all honesty, I had and have no interest in colouring books. Except that Chaosium, Inc. published a colouring book, one inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft. It being from Chaosium, Inc. and it being inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft piqued my interest enough to want to review it, but the main reason to do so was to see if I could review an actual colouring book. Well, I could, and the result was a review of Call of Cthulhu – The Coloring Book: 28 Eldritch Scenes of Lovecraftian for you to Color. However, it turns out it was not the only Lovecraft-inspired colouring book.