It is impossible to ignore the influence of Dungeons & Dragons and the effect that its imprint has had on the gaming hobby. It remains the most popular roleplaying game some forty or more years since it was first published, and it is a design and a set-up which for many was their first experience of roleplaying—and one to which they return again and again. This explains the popularity of the Old School Renaissance and the many retroclones—roleplaying games which seek to emulate the mechanics and play style of previous editions Dungeons & Dragons—which that movement has spawned in the last fifteen years. Just as with the Indie Game movement before it began as an amateur endeavour, so did the Old School Renaissance, and just as with the Indie Game movement before it, many of the aspects of the Old School Renaissance are being adopted by mainstream roleplaying publishers who go on to publish retroclones of their own. Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game, published by Goodman Games is a perfect example of this. Other publishers have been around long enough for them to publish new editions of their games which originally appeared in the first few years of the hobby, whilst still others are taking their new, more contemporary games and mapping them onto the retroclone.

Yet there are other roleplaying games which draw upon the roleplaying games of the 1970s, part of the Old School Renaissance, but which may not necessarily draw directly upon

Dungeons & Dragons. Some are new, like

Forbidden Lands – Raiders & Rogues in a Cursed World and

Classic Fantasy: Dungeoneering Adventures, d100 Style!, but others are almost as old as

Dungeons & Dragons. One of these is

The Fantasy Trip, published by Metagaming Concepts in 1980. Designed by Steve Jackson, this was a fantasy roleplaying game built around two earlier microgames, also designed by Steve Jackson,

MicroGame #3: Melee in 1977 and

MicroGame #6: Wizard in 1978. With the closure of Metagaming Concepts in 1983,

The Fantasy Trip and its various titles went out of print. Steve Jackson would go on to found Steve Jackson Games and design further titles like

Car Wars and

Munchkin as well as the detailed, universal roleplaying game, GURPS. Then in December, 2017, Steve Jackson

announced that he had got the rights back to

The Fantasy Trip and then in April, 2019, following a successful

Kickstarter campaign Steve Jackson Games republished

The Fantasy Trip. The mascot version of

The Fantasy Trip is of course,

The Fantasy Trip: Legacy Edition.

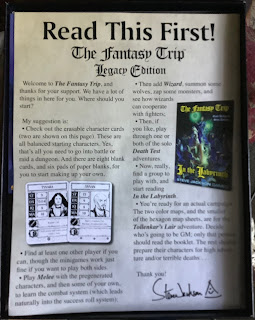

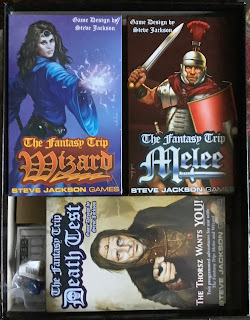

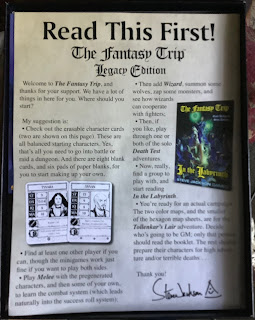

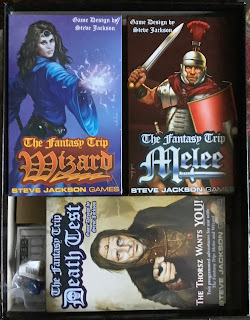

The Fantasy Trip: Legacy Edition

The Fantasy Trip: Legacy Edition is a big box of things, including the original two microgames. So instead of reviewing the deep box as a whole, it is worth examining the constituent parts of

The Fantasy Trip: Legacy Edition one by one, delving ever deeper into its depths bit by bit. The first of these is

Melee, quick to set up, quick to play game of man-to-man combat, followed by

Wizard, which did exactly the same for sorcerers and other magic-users. The third part of this triumvirate is

Death Test, which combined the two original scenarios—‘Death Test’ and ‘Death Test 2’—both originally published as

MicroQuest 1: Death Test and

MicroQuest 1: Death Test 2 in 1980. bringing the trilogy of mini-boxed sets together is

The Fantasy Trip: In the Labyrinth. This is not yet another mini-box, but a book which combines their content into one volume and expands upon with further rules, expansions, and options which lift

Melee and

Wizard up from being combat and magical skirmish games respectively into an actual roleplaying game. What it lacks though is the counters and maps to be found both in

Melee and

Wizard, but that is not an issue with

The Fantasy Trip: Legacy Edition.

The Fantasy Trip: In the Labyrinth

The Fantasy Trip: In the Labyrinth is a combination of three books for

The Fantasy Trip. The first two are

Advanced Melee and

Advanced Wizard which provided expanded rules for

Melee and

Wizard respectively. The third is

In the Labyrinth: Game Masters’ Campaign and Adventure Guide, published originally in 1980, which added a role-playing system and a fantasy-world background for the whole of

The Fantasy Trip line, as well as introducing a point-buy skill system for the system as whole—rather than just spells in

Wizard. The new version of In the Labyrinth collates all of that content into one supplement for

The Fantasy Trip Legacy Edition. It includes rules for creating characters, the core mechanics, notes on designing labyrinths, rules for both advanced combat and advanced magic, and it introduces the setting of Cidri, including a lengthy bestiary. All that, that there are two notable aspects to

In the Labyrinth. First, the Game Master and her players could just start with

In the Labyrinth as their introduction to

The Fantasy Trip, instead of

Melee and

Wizard (and

Death Test). That might steepen the learning curve though, and there is something to be said of the experience of trying out the basics of both games prior to coming to In the Labyrinth, though the supplement does serve as the capstone for

The Fantasy Trip. Second,

In the Labyrinth and

The Fantasy Trip look like any other generic fantasy system, but dig down into the mechanics and the setting details, and whilst on one level, it does look fairly generic—and could be run as generic fantasy, it really is quite a bit different.

After introducing and explaining the concept of roleplaying,

In the Labyrinth introduces the world of Cidri. This is a large world with an Earth-like gravity and environments, which until a few hundred years ago was the playground of an ancient all-powerful race of dimension travellers called the Mnoren. It was one of many worlds they created before they disappeared, but this has many continents, many of them connected by magical gates, and many peoples imported from the original Earth. Consequently, historical faiths and cultures of Earth can be found on Cidri, so Vikings, Aztecs, Persians, Samurai, and so on, can all be found on the world—somewhere. As can adherents of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, as well as those faith to gods and goddesses and pantheons unknown on Earth. Notably, whilst there are numerous faiths and religions to be found on Cidri, along with their priests, churches, and temples, the gods themselves do not appear in the world, and it is actually possible for the devout to achieve apotheosis. This mix of the fantastic and the real explains the cover to

In the Labyrinth, which shows a wizard, a priest, a Norman knight, and a Roman legionnaire together best by monsters, a mix which otherwise be incongruous. What it also means is that almost any fantasy or historical setting can be dropped into the Cidri, such is the scale and scope of the planet.

In comparison to most fantasy settings, Cidri is relatively technologically advanced, gunpowder being known, but expensive—requiring dragon dung, and gunpowder weapons being unreliable. Despite these technological advances, magic is more prevalent and the Wizards’ Guild holds no little influence and power—far more than the Mechanicians’ Guild. Other guilds include the Thieves’ Guild, the Scholars’ Guild, the Mercenaries’ Guild. Alongside the guilds,

In the Labyrinth covers various jobs and occupations which the Player Characters can have when not actually adventuring and so earn an honest (or dishonest depending upon occupation) income.

A character in

In the Labyrinth and thus

The Fantasy Trip is defined by three attributes—Strength (ST), Dexterity (DX), and Intelligence (IQ). Strength covers how many hits a character has, what weapons he can use, how effective he is in hand-to-hand combat, and for a Wizard, how many spells he can cast, each spell having a cost that is paid in Strength points, not only to cast the spell, but also maintain it if necessary. Dexterity covers how easily a Hero or Wizard can hit an opponent, disengage from the enemy, and how quickly he can attack. Intelligence governs the number of spells a Wizard knows, the maximum level of spells he knows—each spell has an IQ rating between eight and sixteen which the Wizard’s Intelligence must match for him to know, and his resistance to illusions and Control spells. With

In the Labyrinth, Intelligence is also how many Talents a character knows. Both Heroes and Wizards can learn spells and Talents, but Heroes learn spells with great difficulty, just as Wizards learn Talents with great difficulty.

In the Labyrinth and

The Fantasy Trip is not a Class and Level system, but a Class and Spell or Talent system. It has only has the two Classes—Hero and Wizard. Yet, a Hero need not be the fighter of

Melee and a

Wizard need not be the classic adventuring wizard a la

Dungeons & Dragons, guidelines being included to cover everything from the barbarian, the gadgeteer, and the merchant to the martial wizard, townsman wizard, and the wizardly thief. It is possible to create a priest, which can be a simple cleric or monk, or may actually know a limited number of spells. However, technically such priests would be Wizards with a Talent or two or a Hero who knows a spell or two.

In the Labyrinth expands upon Wizard to include over one-hundred-and-fifty spells. These all have a minimum IQ rating to understand, from IQ 8 to IQ 20 and a ST cost to cast, and if necessary, to maintain. So they range from the simple Blur at IQ 8, a defensive spell which levies a penalty on DX when attacking the caster and costs 1 ST to cast and maintain to the IQ 20 Word of Command which costs 3 ST and affects those that fail their save for a whole minute. Typical words include ‘Believe’, ‘Come’, and ‘Quiet’, and the Wizard needs to learn the spell for each word. Similarly, it adds a range of Talents, which again have a minimum IQ rating for a character to know, from IQ 7 to IQ 14. These have a purchase cost, so the IQ 7 Talent of Brawling costs a point to purchase, whilst the IQ 14 Talent of Alchemy costs three points. Most grant the simple ability to use something like a knife or do something like diplomacy or undertake a profession such as Engineer or Theologian. Many Talents have prerequisites, so that Unarmed Combat I grants the ability to attack punches and kicks more effectively, and then Unarmed Combat II increases the effectiveness and adds ability to throw opponents or evade them, and so on up to Unarmed Combat V.

To create a character, a player takes a base character with ST 8, DX 8, and IQ 8, and divides eight points between them with ten being the human average. Dwarves, Elves, Goblins, and Halflings have different starting values. Then, if a Wizard, the player has points equal to his character’s IQ with which to purchase spells, whilst similarly with a Hero, the player has points equal to his character’s IQ with which to purchase Talents. The process is relatively easy, but a random character generator is provided to speed the process up.

Deodato Patriarca

Human – Hero – HealerMotivation: Desire for adventure

Appearance: Average (5)Bravery: Brave (9)Friendliness: Friendly (8)Honesty: Less than truthful (5)Mood: Shy (4)

Strength 08Dexterity 12Intelligence 12MA 08

Talents: Diplomacy (1), Naturalist (1), Detect Lies (2), Physicker (2), Expert Naturalist (2), Woodsman (1), Courtly Graces (1), Unarmed Combat (1)

Mechanically,

In the Labyrinth and

The Fantasy Trip are simple and straightforward. Whether a character undertakes an action, such as striking an opponent with a sword or following some tracks, or needs to make a Save to avoid an unpleasant or difficult situation, such withstanding the effects of a spell or dodging a falling log trap, his player rolls three six-sided dice and attempts to roll under the appropriate attribute. Rolls of three, four, and five indicate degrees of critical success, whilst rolls of sixteen, seventeen, and eighteen, indicate degrees of critical failure. The attribute may be adjusted, whether that is due to wearing armour or environmental conditions, but the main means of adjusting the difficulty of a task is by increasing or reducing the number of dice a player has to roll, and guidelines cover both critical successes and failures with the adjusted number of dice. It is simple and it is quick, and as a logical extension of both Melee and Wizard it presents a relatively easy learning curve.

Where

In the Labyrinth and

The Fantasy Trip becomes complex is in the advanced rules for both combat and magic. Advanced Combat is designed to cover just about every situation imaginable, starting from the combat order and options such as dodging, charging, disengaging, and casting spells to weapon types, fighting on broken ground, stairs, and in narrow tunnels, ambushes, unarmed combat, gunpowder bombs, taking prisoners, and more… The options are neatly explained and the Advanced Combat rules are backed up with a solid example of combat in play. Magic is treated as comprehensively in Advanced Magic. Thus types of spells—missile and thrown spells, control spells, illusions—including their limitations and even their disbelief by animals, and casting from both books and spells. Both of the latter take more time, but where casting from a scroll can be done in combat, casting from a book cannot. There is a complete guide to casting that most wanted spell, Wish, plus Advanced Magic takes the Wizard away from adventuring and into the laboratory with rules for alchemy, the enchantment of magical items, and more, accompanied by lists of potions and magical items that the Wizard can manufacture, or perhaps when adventuring, discover with his fellow Wizards and Heroes.

Expanding upon

Melee and

Wizard, the bestiary for the world of Cidri in

In the Labyrinth includes over hundred different entries, from humanoids, intelligent monsters, and ghosts, wights, and revenants to water creatures, plants, and nuisance creatures—the latter amusingly including children! All of the humanoid races are playable, with Orcs being more vicious rather than evil, Goblins being crafty and capable of giving and keeping their word rather than again being evil or nasty, and Gargoyles turn out to be tough and trustworthy, but distrust others because their gallbladders are used by alchemists in various different potions. The only addition to the humanoids on Cidri are the silly, annoying Prootwaddles, whilst the major addition to intelligent races are Octopi, which are capable of walking on land and wielding weapons and shields, but are cowardly, greedy, and dishonest! In the main, the various entries in

In the Labyrinth’s bestiary will be familiar from other fantasy roleplaying games, but in many cases, there are little differences which will make adventuring on Cidri a different experience. So Vampires and Werewolves are actually suffering from a disease which they can pass on and can be cured of, and Wights, whilst undead, have a physical form that can attack and be attacked, and further, may not necessarily be evil. In some ways, it is this bestiary which showcases the default setting for

The Fantasy Trip the best.

In addition,

In the Labyrinth includes rules and guidelines on creating and stocking labyrinths and on taking the game beyond the confines of such a labyrinth. Along with a few random tables to help stock both locations, these sections are relatively short, almost as if the actual labyrinths are not necessarily the focus despite the title of the supplement. There is a sample labyrinth included though, just a few locations and it is used in the example of combat later in the supplement. That said, the labyrinths do look weird done on hex maps rather than the square maps we are used to after decades of

Dungeons & Dragons. Rounding out

In the Labyrinth are descriptions of the village of Bendwyn and the Duchy of Dran in Southern Elyntia, both a couple of pages in length. These are very much a starting point for the prospective Game Master to develop, so a little basic, but nevertheless with a few hooks that she can employ.

Physically,

In the Labyrinth looks a little old-fashioned by being black and white throughout, and whilst the artwork varies in quality, some of it is excellent and some of it feels anachronistic in places. Nevertheless, it is a cleanly presented book and it is all very readable.

Despite originally having been published in 1980,

In the Labyrinth feels modern. Part of this is down to the presentation—clean, bright, and tidy, just as you would expect from Steve Jackson Games, but in the main, it is due to it being a point-buy system. In fact, one of the earliest of point-buy systems and probably one of the simplest. That simplicity is where

In the Labyrinth shines, providing the means to run a fantasy roleplaying system that the Game Master and her group with a solid starting point upon which to add the advanced rules. The simplicity also provides a flexibility in terms character creation, suggestions being given to create numerous different types of character, but still only using what are effectively, two different Classes. Another reason that

In the Labyrinth feels modern is that in its design can be seen the genesis of Steve Jackson Games’ other great roleplaying design—

GURPS. So many of the elements of

In the Labyrinth would go on to inform or even appear in one of the great generic point-buy roleplaying systems.

As much as

In the Labyrinth effectively explains and showcases the mechanics of The Fantasy Trip, it is less successful at showcasing the world of Cidri. At best the description of the giant multi-continent world of Cidri is an introduction to and explanation of why it is, but at worst, that explanation is bland and uninteresting. The problem here is that Cidri is presented as an every-world, a world that can have every historical setting in it plus fantasy, and whilst that gives the Game Master a lot of scope, it is also intimidating and it really does not give the Game Master a starting point. It should feel fantastic, but despite being fantasy, it does not. A more experienced Game Master will have less of a problem with this and be able to develop more of the setting herself, playing around with the potentially intriguing mix of real world and fantasy cultures rubbing up against each other.

In the Labyrinth is a great supplement, packing a lot of well-explained and well-presented options into its pages. The result lifts the combat and magic-focused play of

Melee and

Wizard into a fully rounded

The Fantasy Trip roleplaying game.

Name: Prisoners’ DilemmaPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: Prisoners’ DilemmaPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.