Monster Brains

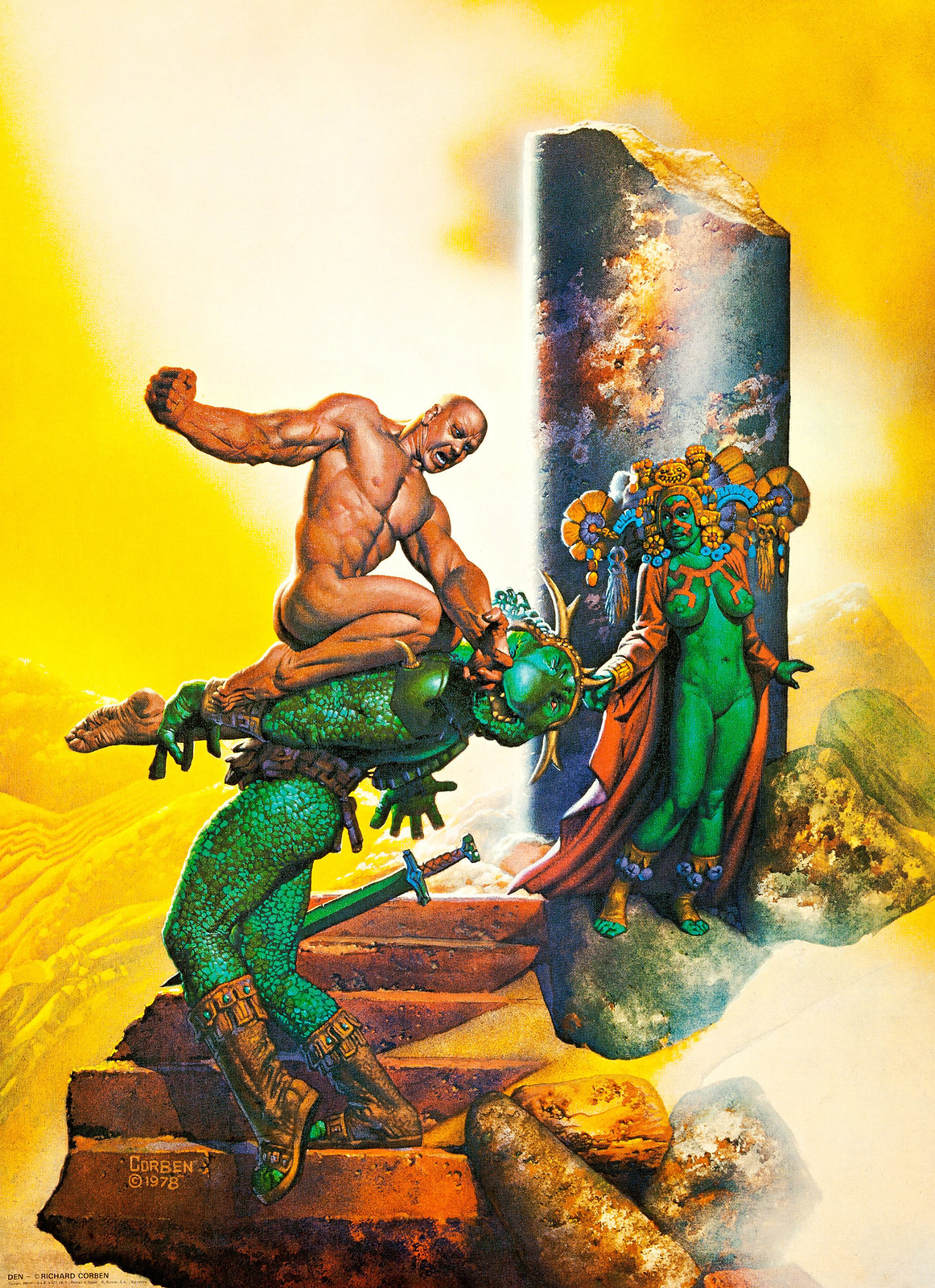

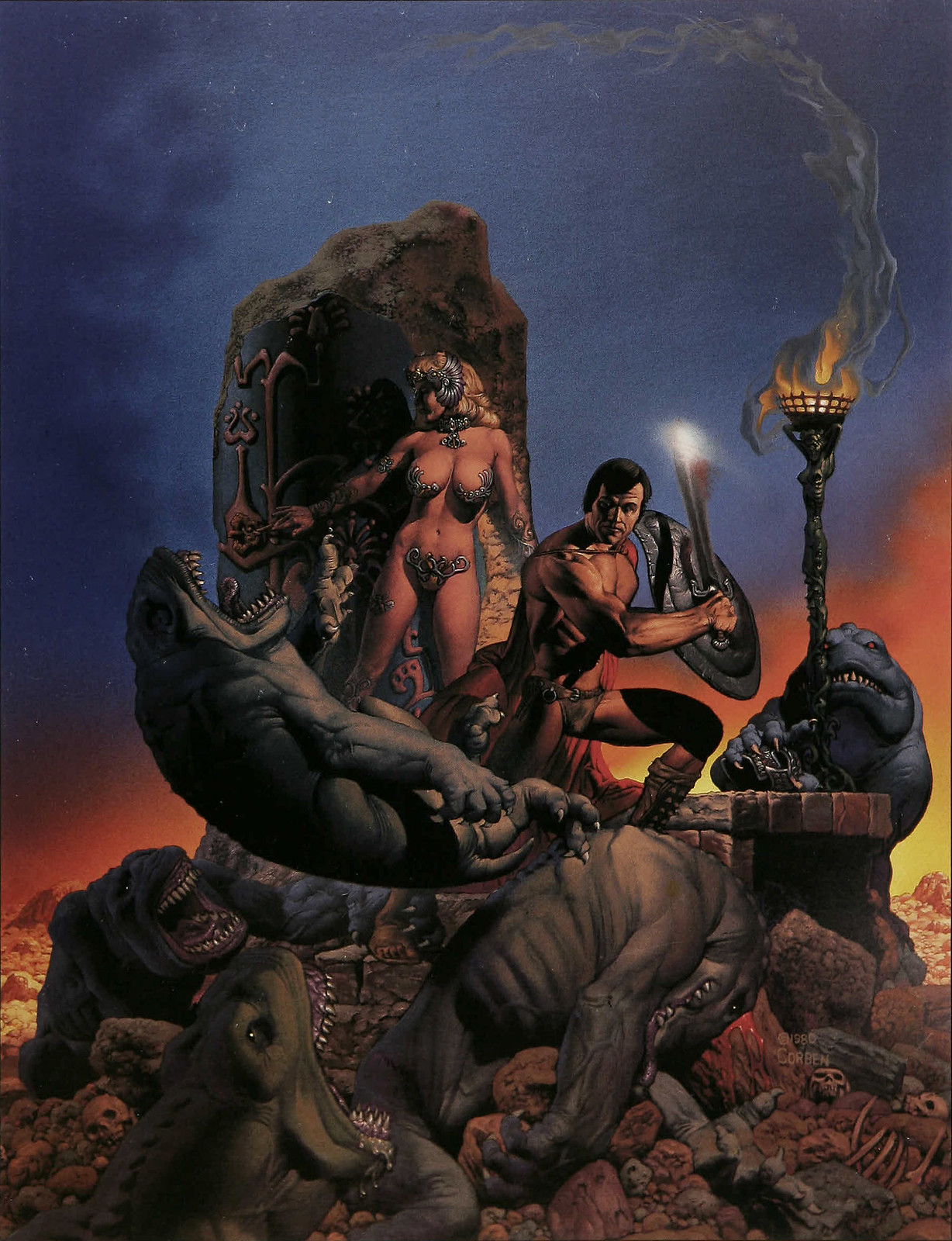

Horacio Salinas Blanch - Cover Art for "Super Fiction Collection" 1976 – 1986

"Downward to the Earth" by Robert Silverberg, 1981

"Downward to the Earth" by Robert Silverberg, 1981

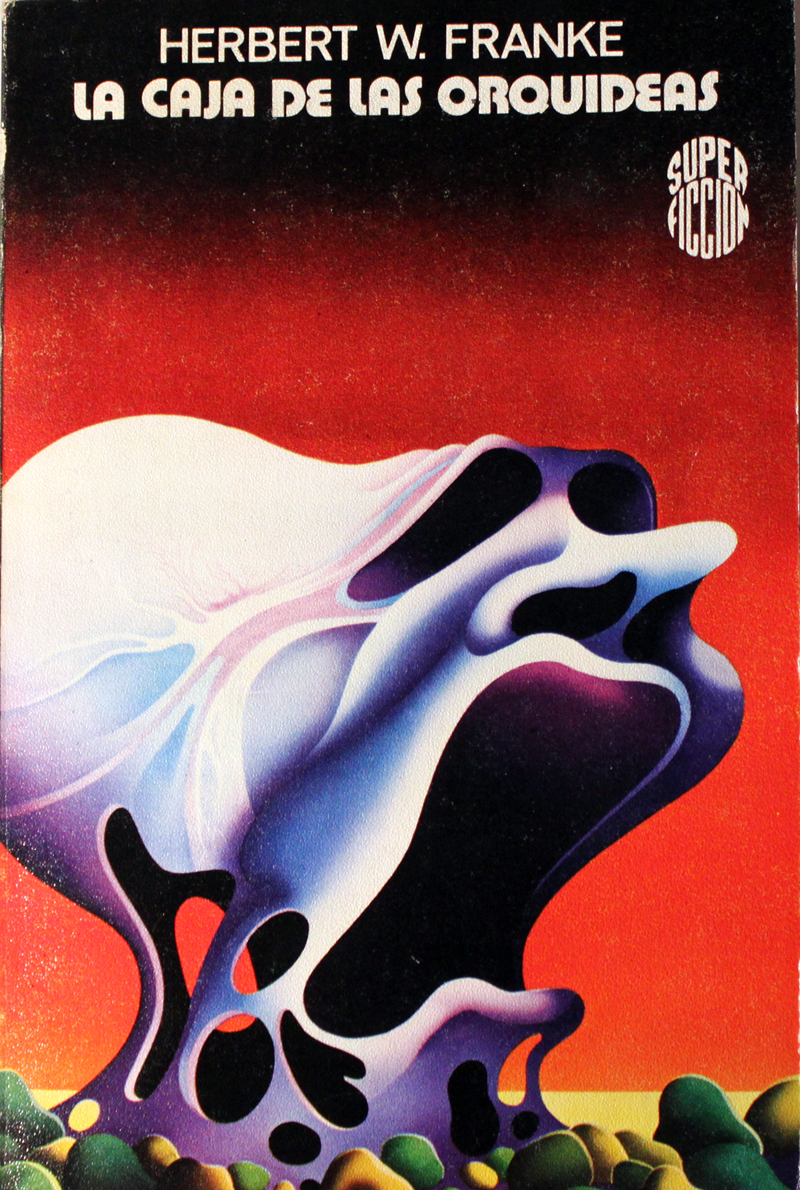

"The Orchid Cage" by Herbert W. Franke, 1978

"The Orchid Cage" by Herbert W. Franke, 1978

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum, 1977

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum, 1977

"Brainrack" by Gerry Davis/Kit Pedler, 1976

"Brainrack" by Gerry Davis/Kit Pedler, 1976

"Desert of Fog and Ashes" by Joan Trigo, 1978

"Desert of Fog and Ashes" by Joan Trigo, 1978

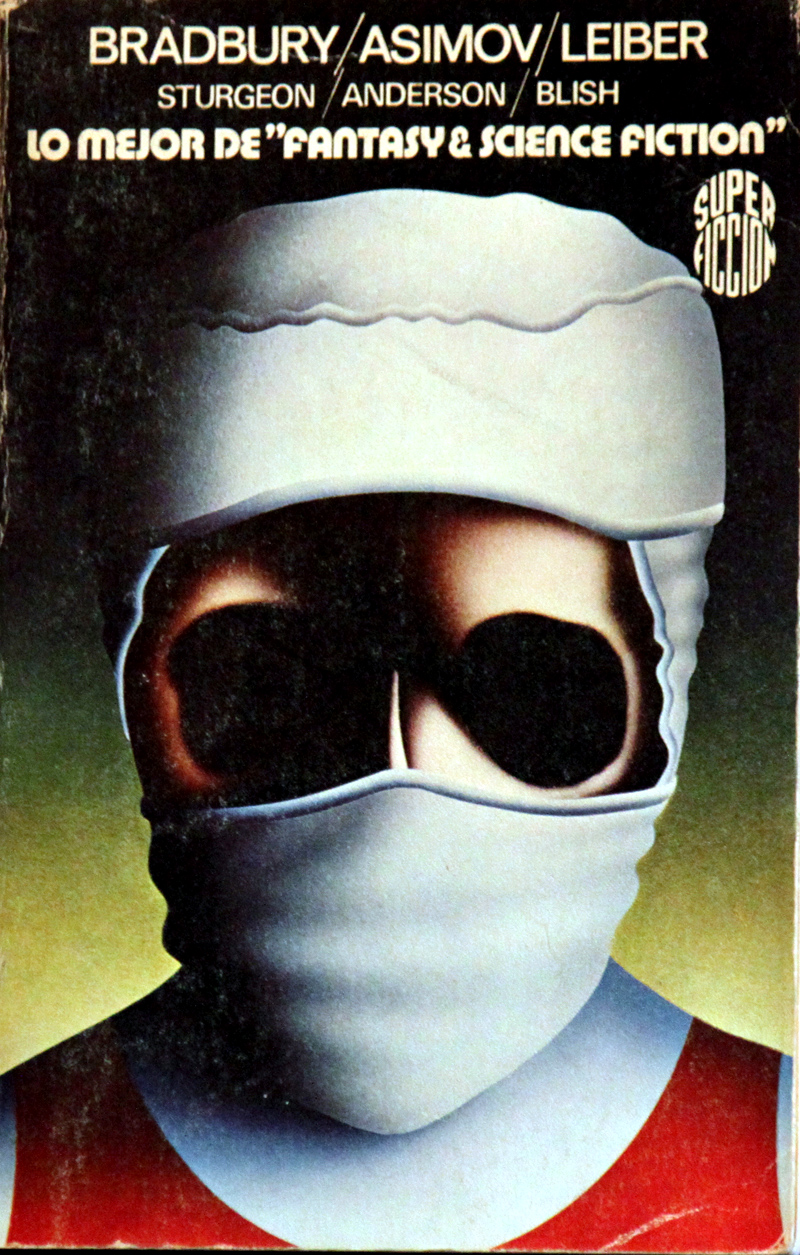

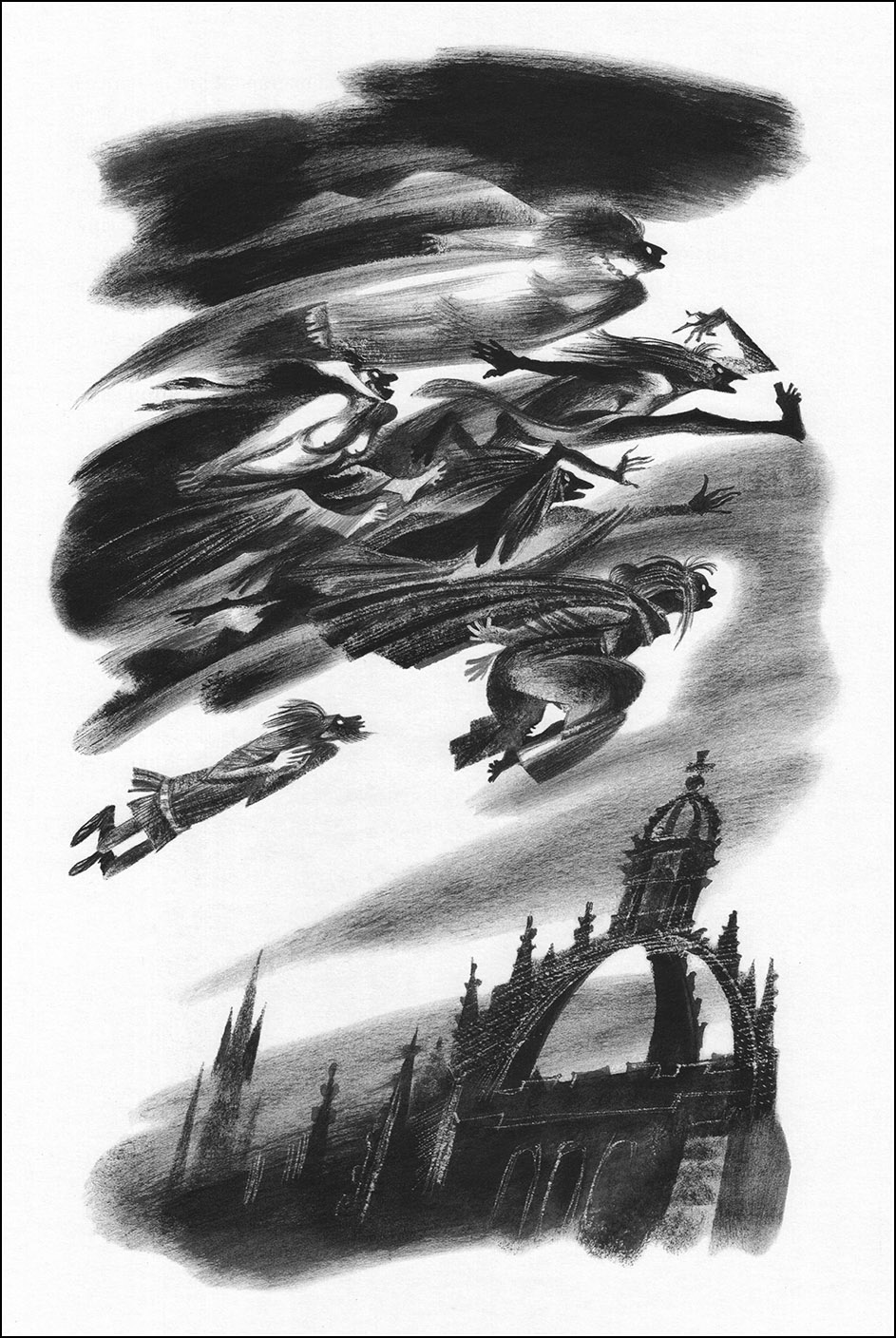

The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, 25th Anniversary Anthology, 1976

The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, 25th Anniversary Anthology, 1976

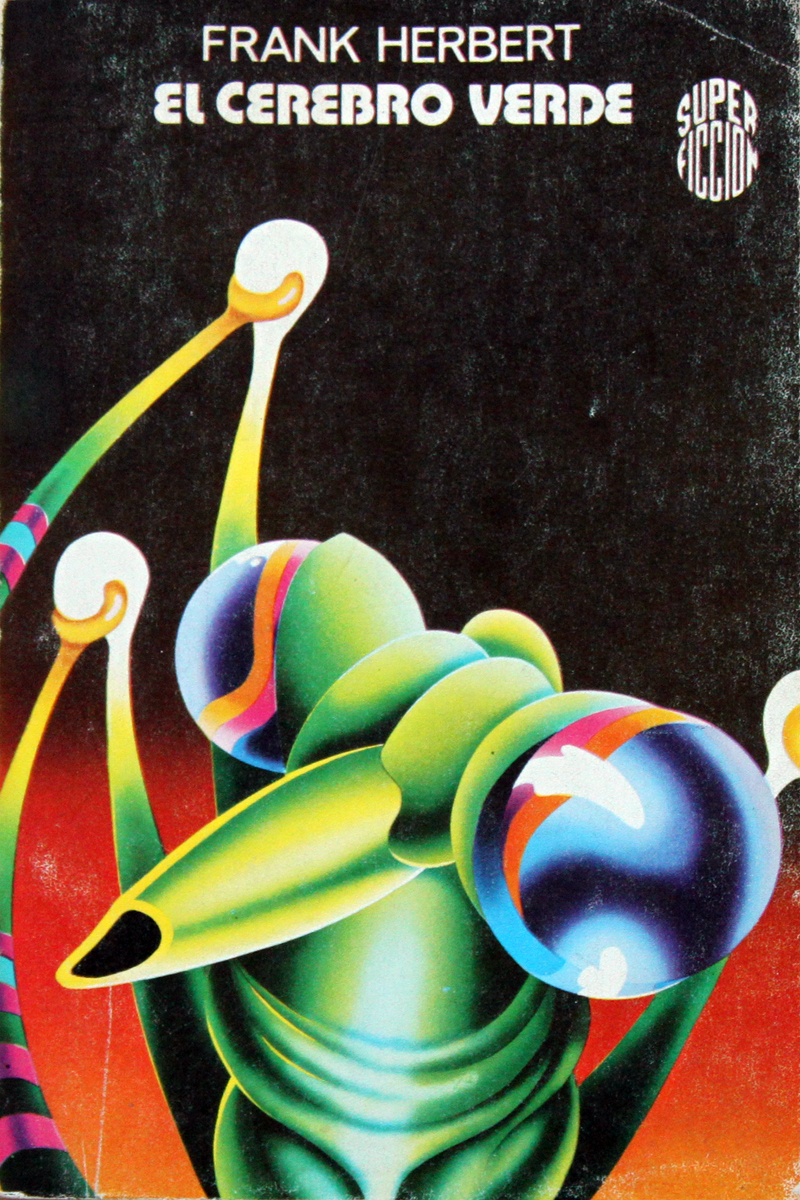

"The Green Brain" by Frank Herbert, 1978

"The Green Brain" by Frank Herbert, 1978

"The I. Q. Merchant" by John Boyd, 1977

"The I. Q. Merchant" by John Boyd, 1977

"Our Children's Children" by Clifford D. Simak, 1976

"Our Children's Children" by Clifford D. Simak, 1976

"Before the Golden Age" Isaac Asimov, 1976

"Before the Golden Age" Isaac Asimov, 1976

"In 1976, the year after the death of Spanish military dictator Francisco Franco, Barcelona publisher Ediciones Martínez Roca launched its Colección "Super Ficción series—an eclectic collection of science fiction novels—with Los Hijos de Nuestros Hijos, a Spanish translation of Clifford Simak’s Our Children’s Children. Los Hijos de Nuestros Hijos and the titles that initially followed it featured cover art created for UK publisher Penguin’s science fiction series. They were the work of David Pelham, who was then Penguin’s art director, as well as the artist behind many of the company’s most memorable covers (one of the best-known being Penguin’s 1972 re-release of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange). ""While in the process of commissioning German surrealist "Konrad Klapheck to provide covers for 1974 reissues of several of J.G. Ballard’s early novels, Pelham took it upon himself, at Ballard’s urging, to realize some of the ideas himself, and it was these that Penguin ended up using.

For the cover of its edition of Jack Williamson’s The Legion of Space, the ninth release in the series, Ediciones Martínez Roca turned to artist Horacio Salinas Blanch. Over the following decade, Salinas Blanch would produce dozens of covers for Colección "Super Ficción". Although his illustration for La Legión del Espacio was relatively restrained, Salinas Blanch’s work—presumably under the instructions of the publishers—took as its template the airbrushed aesthetic of "Pelham’s Ballard covers, where odd juxtapositions of forms rendered with eerie smoothness hovered in isolation against brooding backgrounds. Salinas Blanch, though, approached the concept through his own otherworldly, idiosyncratic lens: pop culture reimagined as art, reimagined once again as pop culture, a circular transformation of which it seems reasonable to presume Ballard would have approved. Salinas Blanch’s" mixture of airbrushed unreality, pop-art surrealism, and lunatic dreamscapes reads like some crazed cocktail of Pelham and the other artists of the day who were working in a similar visual idiom—names like Peter Haars, Peter Tybus, Heinz Edelmann, Peter Lloyd, Bob Pepper, and Alan Aldridge.

No slouch at an inspired rip-off (see his take on Pelham’s cover for Fred Hoyle’s October the First Is Too Late, which Ediciones Martínez Rocahad already used for its cover of a collection of Robert Heinlein’s Lazarus Long stories), Salinas Blanch was not above directly cannibalizing his inspirations, as in this cover art for 1978’s Del Triunfo a la Derrota by Spanish anarchist journalist Jacinto Toryho, where he recycles "Pelham’s Big Boy from the cover of The Terminal Beach, adding a series of powerful details—the low light source, long shadows, and target on the ground. Salinas" Blanch’s other work included cover art for the Spanish translation of Mary Lee Dunn and John Maguire’s book on the Jonestown mass suicide, Hold Hands and Die!, where he offered up a compellingly dreamlike revisitation of an image as famous as it is awful.

Cynical plagiarist, pragmatic jobbing scribbler, or a genuine visionary? It’s hard to say—practically no information about Horacio Salinas Blanch is to be found outside of his corpus of work: his covers, which inhabit the happy intersection of crowd-pleasing commercial interest and fine art inspiration passed through many hands as in a game of telephone, creating something at once known and strange, like some shared archetypal folk memory.

It’s one of the great truisms and paradoxes that it’s occasionally imitation—especially imitation of the crassest, most commercially-driven type—that highlights the essence of what makes something engaging, either by contrasting it with an inferior copy or, as in the case of Horacio Salinas Blanch, by reiterating and mutating the source material until a perfect synthesis of what makes it strange and beautiful has been achieved—and until the imitation itself has become something strange and beautiful too." - quote taken from an excellent article on the artist with additional artworks at We Are The Mutants.

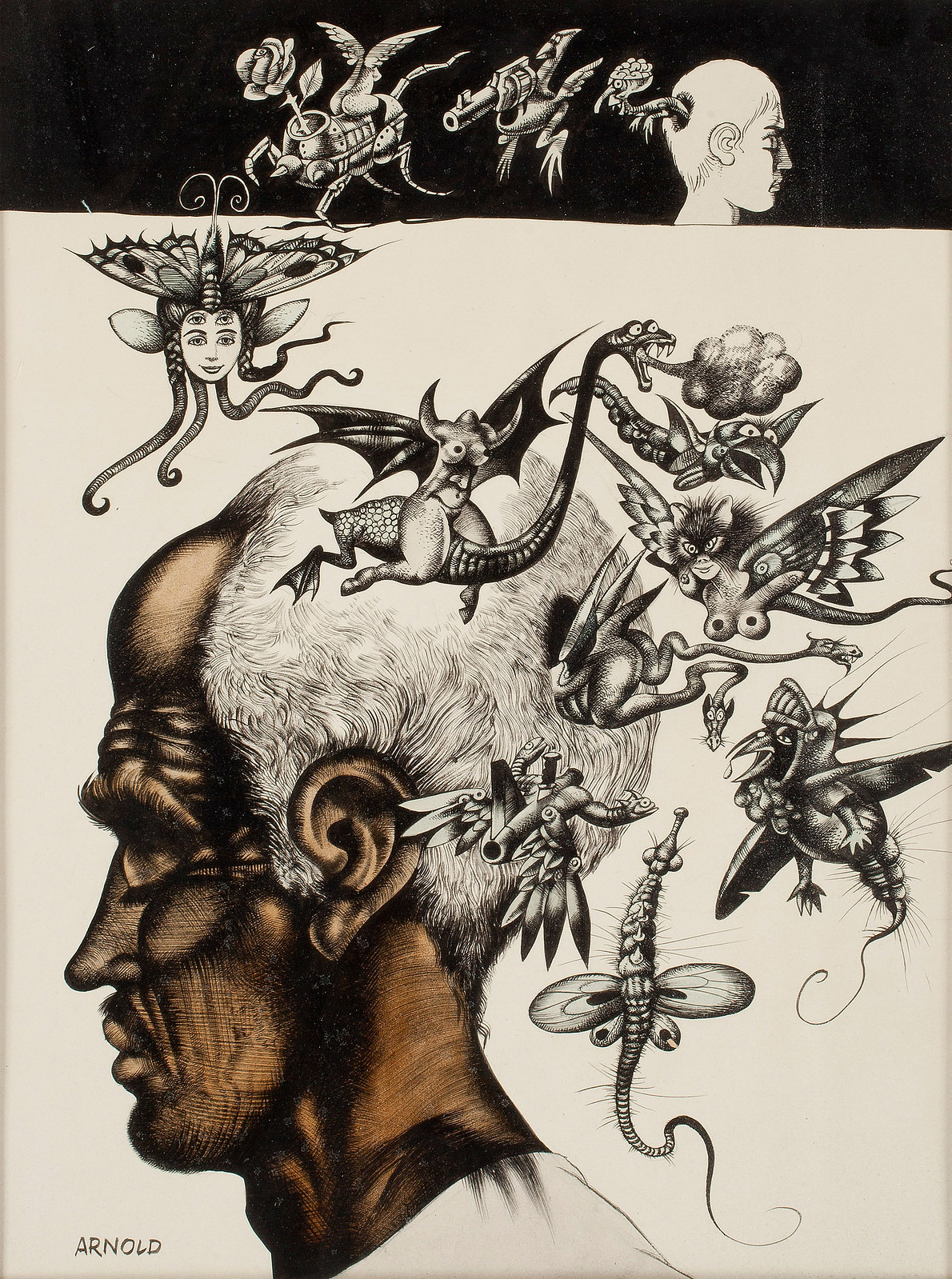

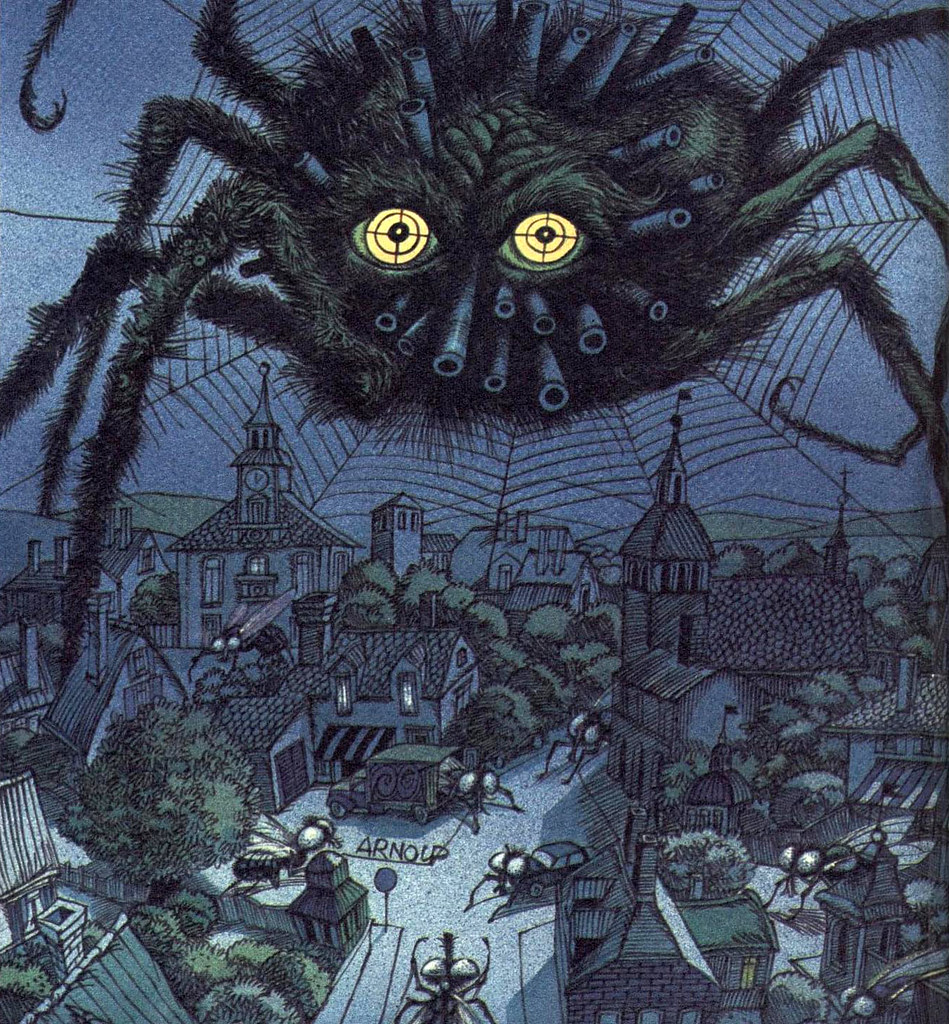

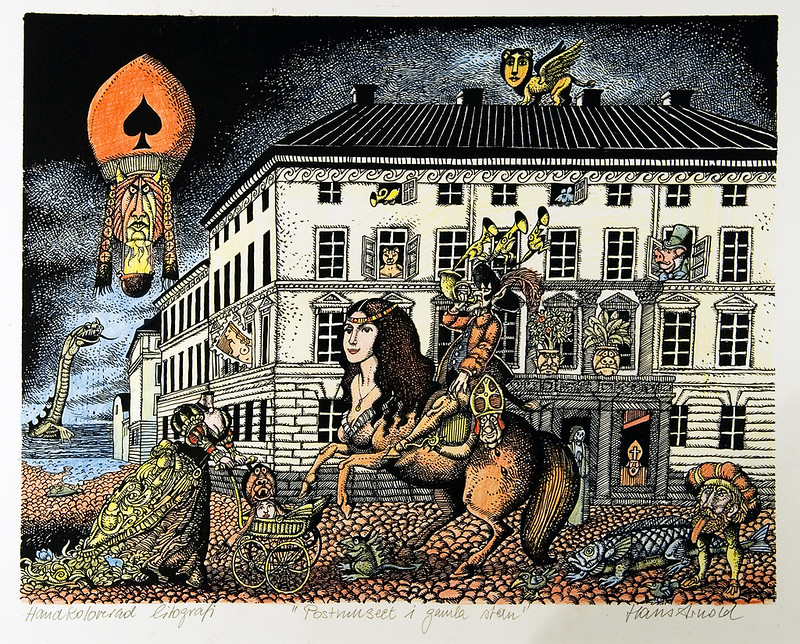

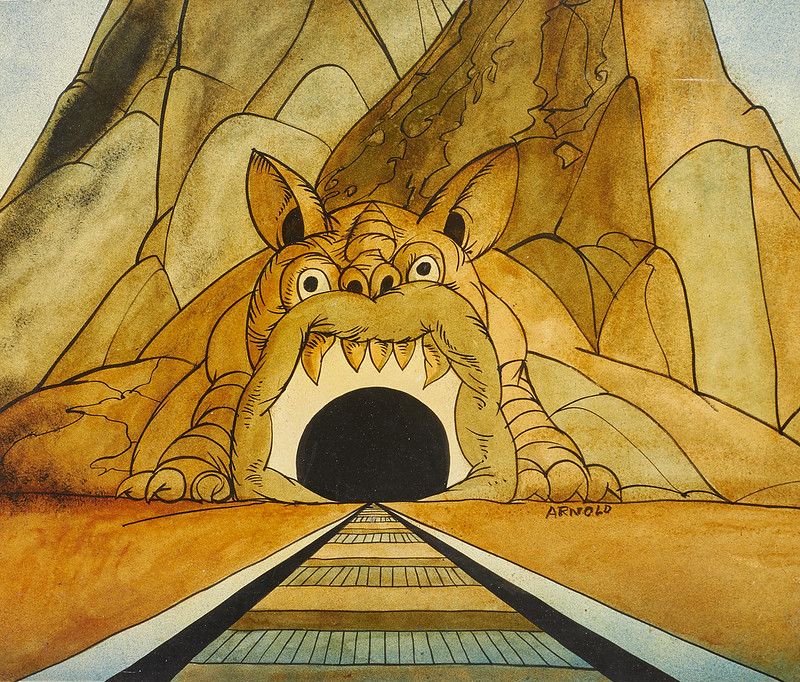

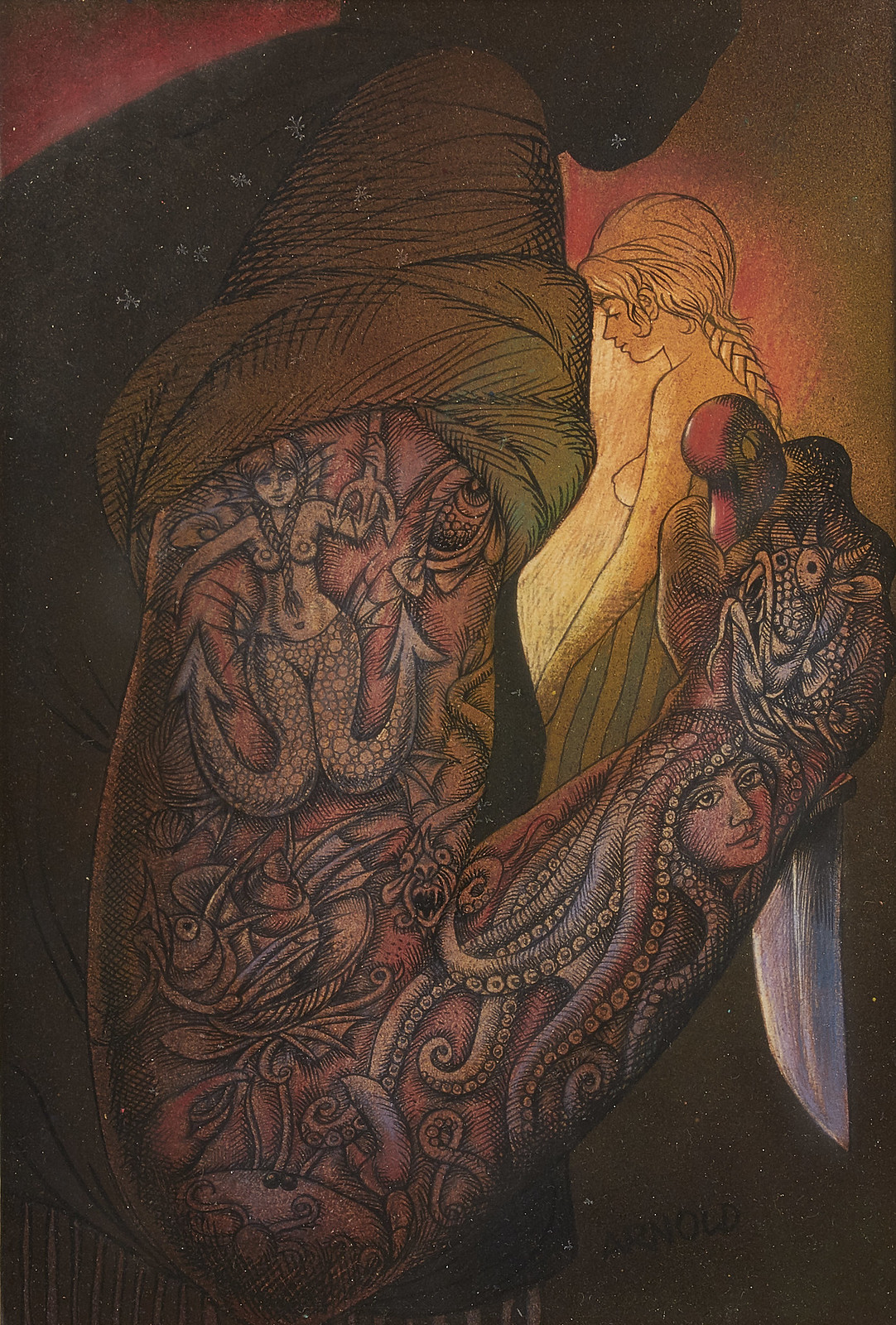

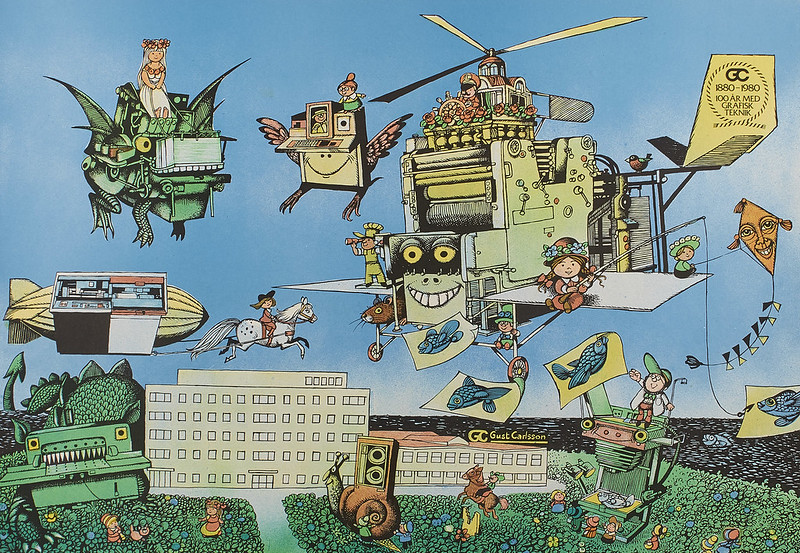

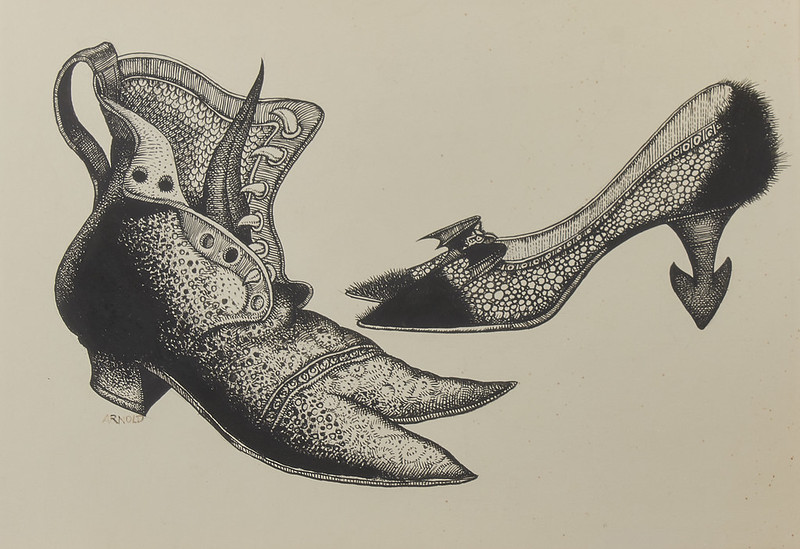

Hans Arnold (1925 - 2010)

See dozens more artworks by Hans Arnold, previously shared here.

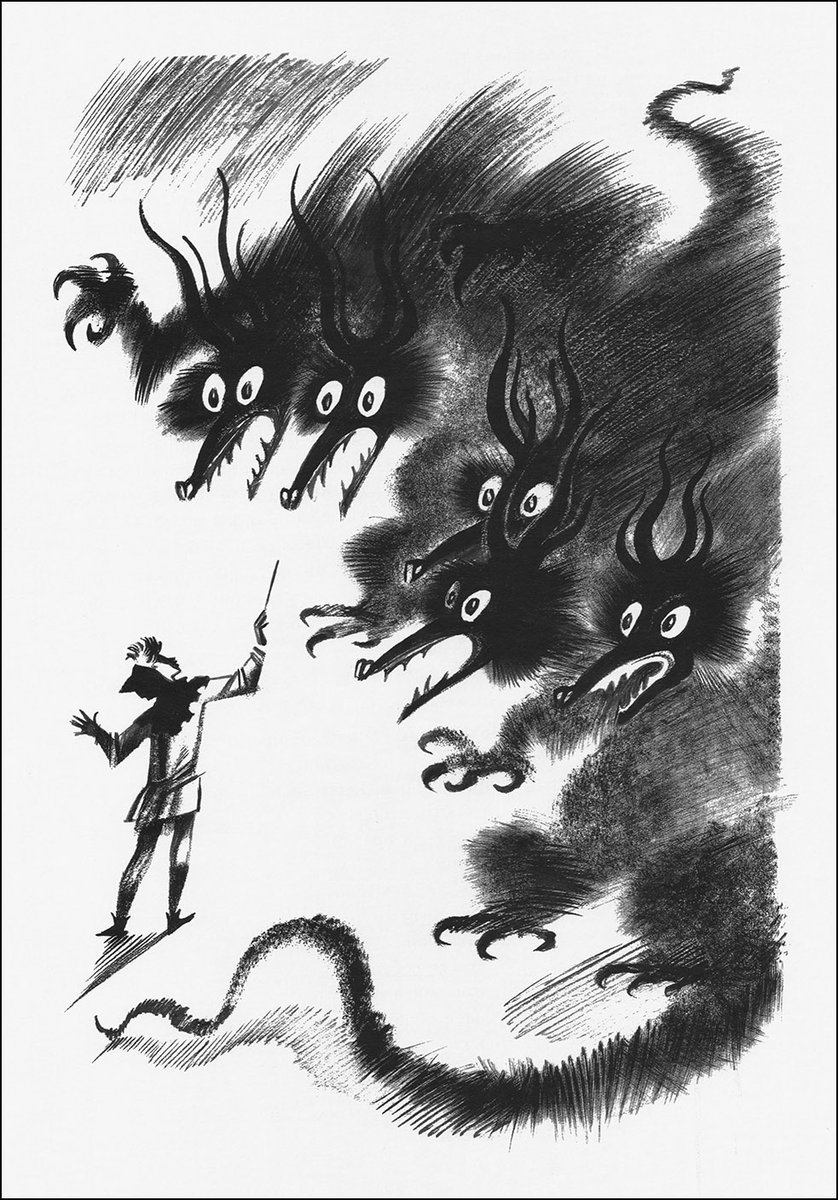

Benon Liberski - They Surround Us On All Sides, 1982

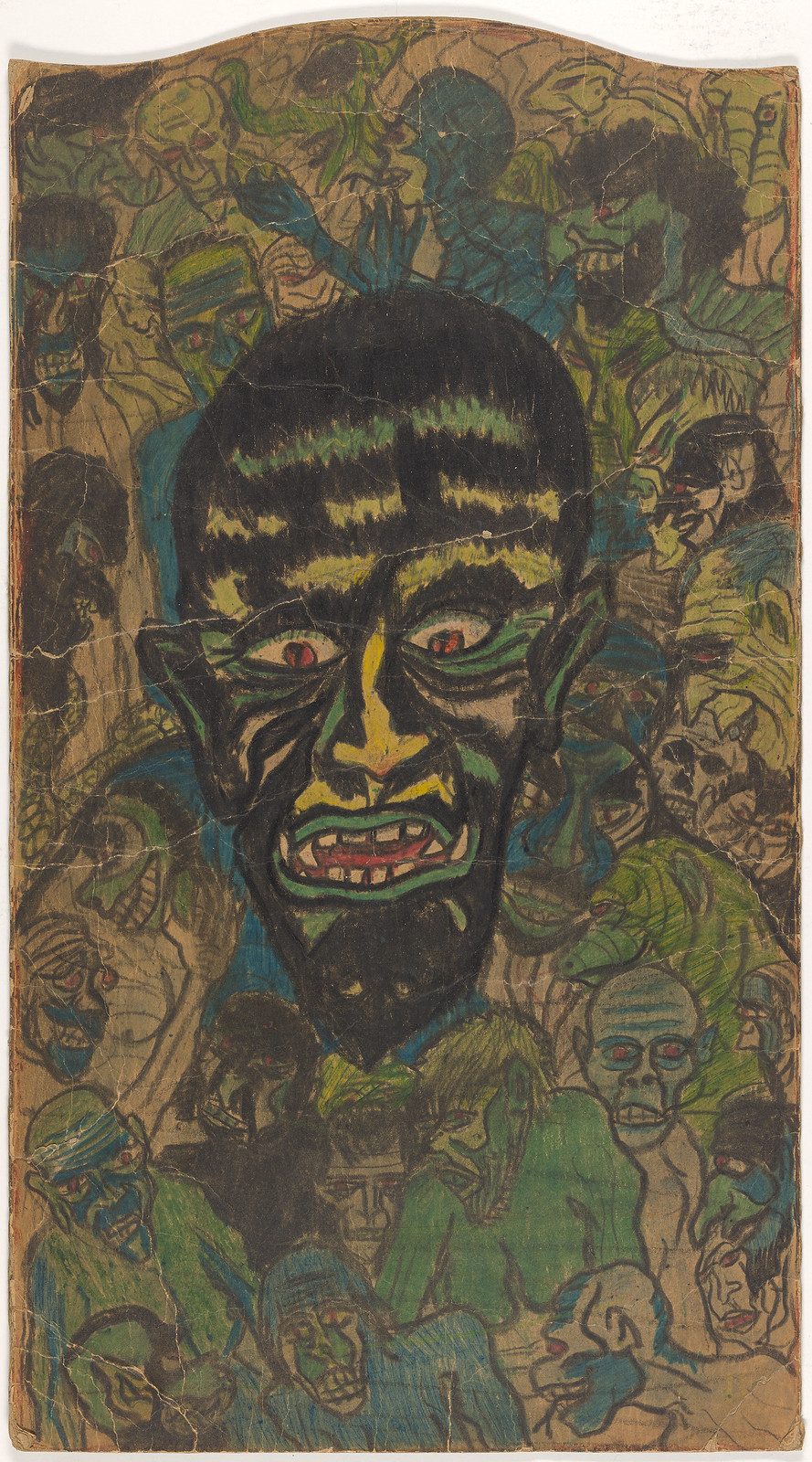

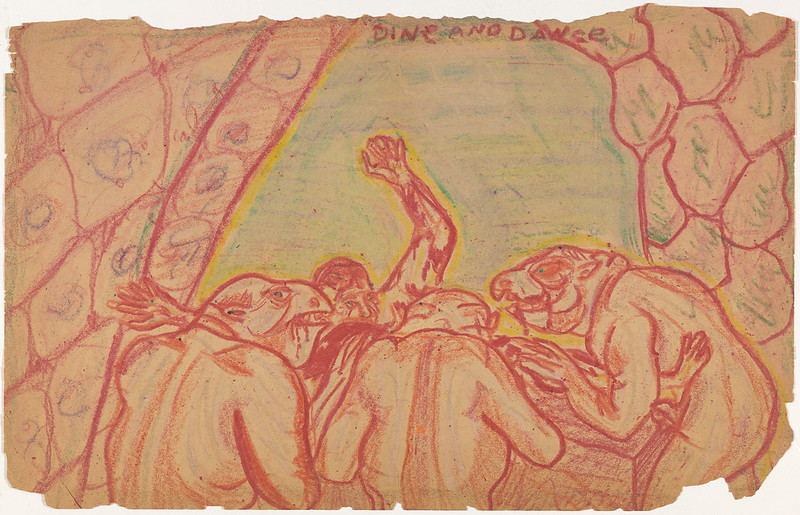

Robert Bloch - H.P Lovecraft Drawings, 1933

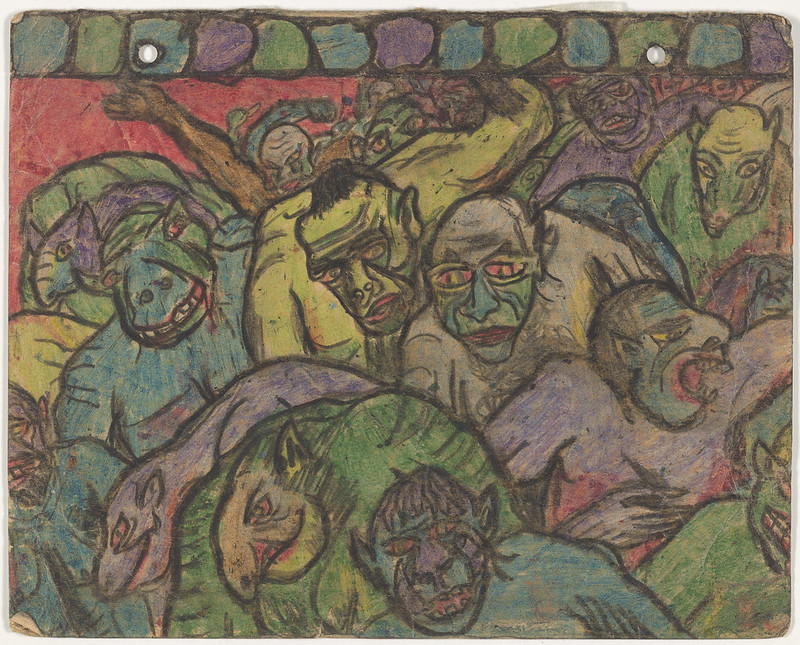

Untitled Lovecraft Artwork

Untitled Lovecraft Artwork  Dine and Dance

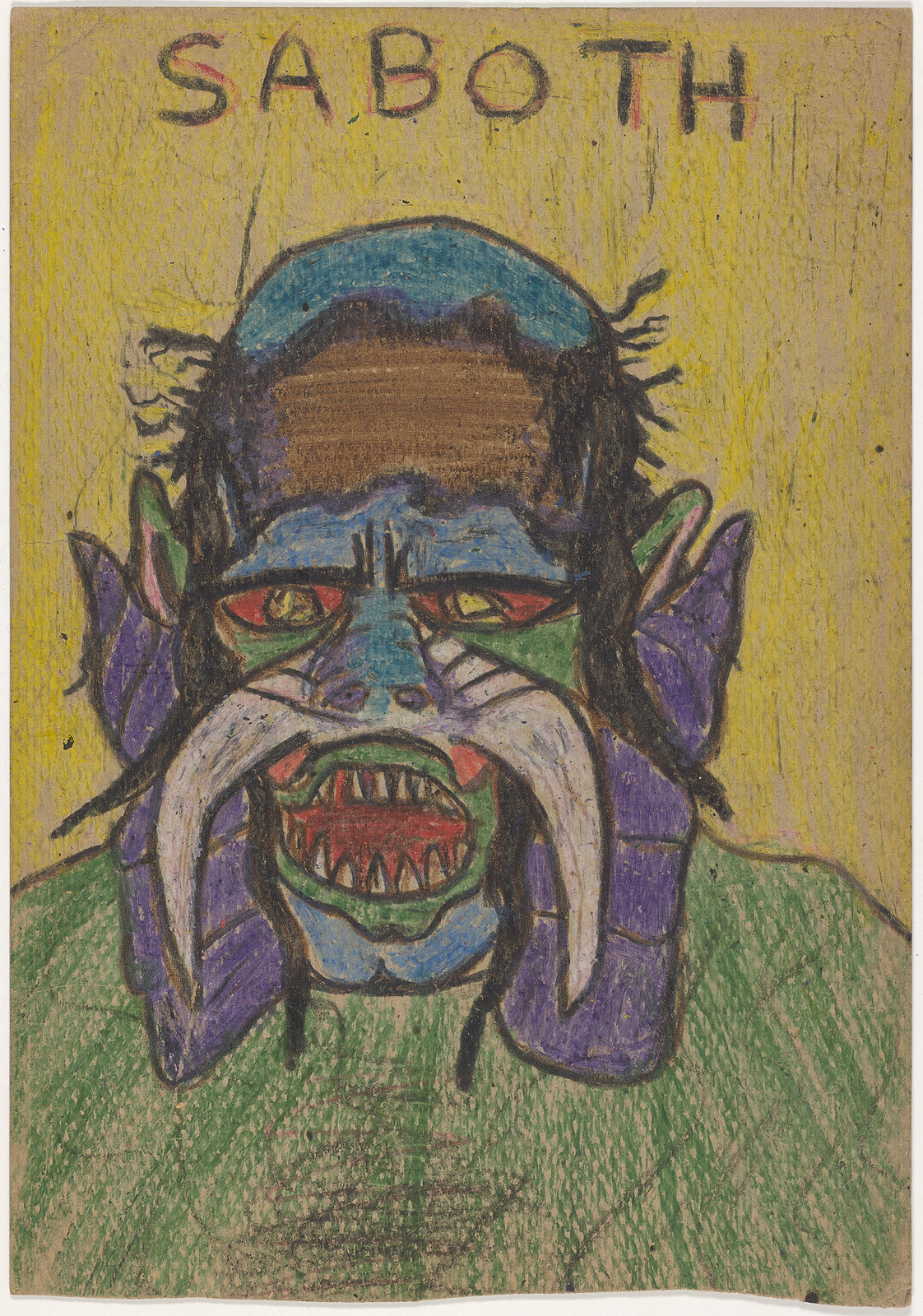

Dine and Dance  Saboth

Saboth  Explorer

Explorer  Untitled Lovecraft Artwork

Untitled Lovecraft Artwork  Abdul Alhazred writing the Necronomicon

Abdul Alhazred writing the Necronomicon  The Ghoul

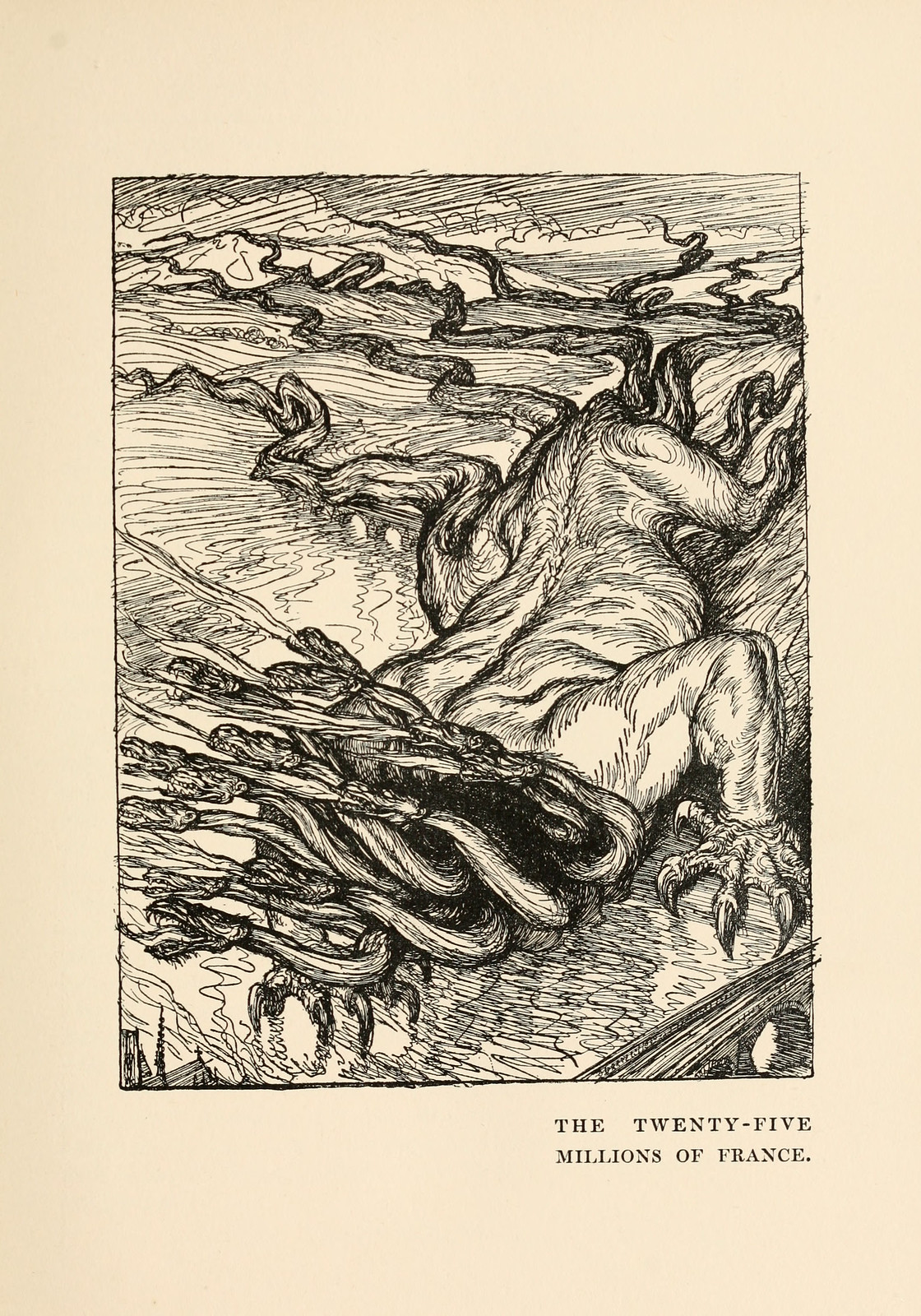

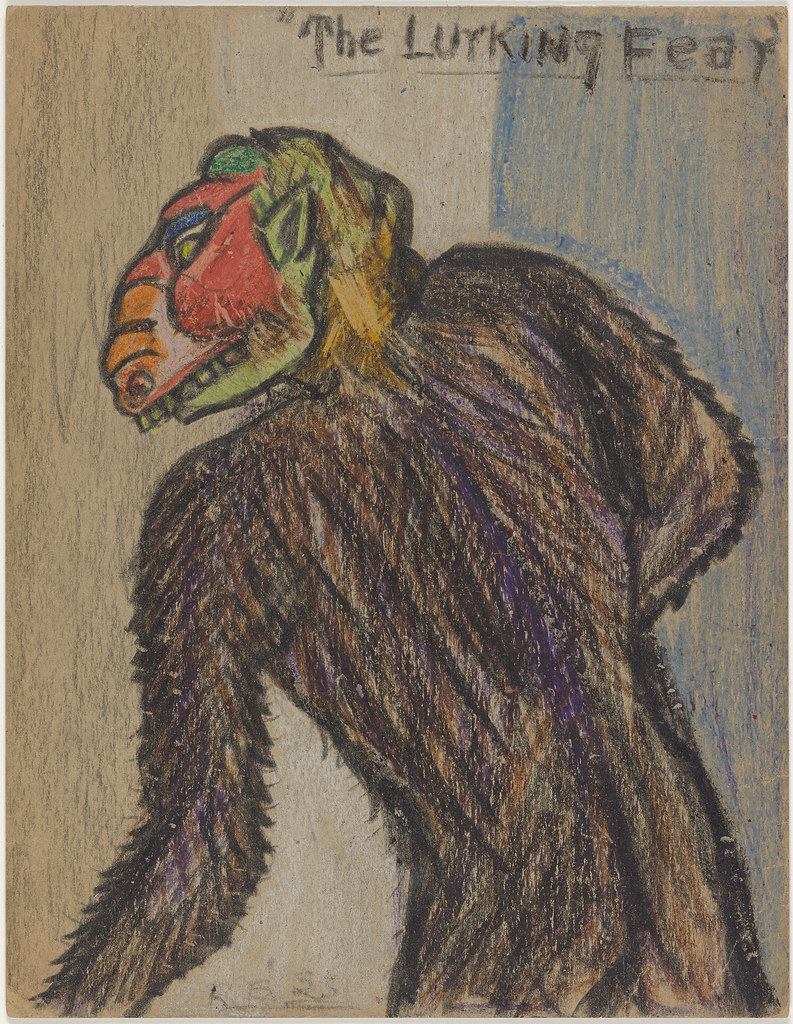

The Ghoul  The Lurking Fear

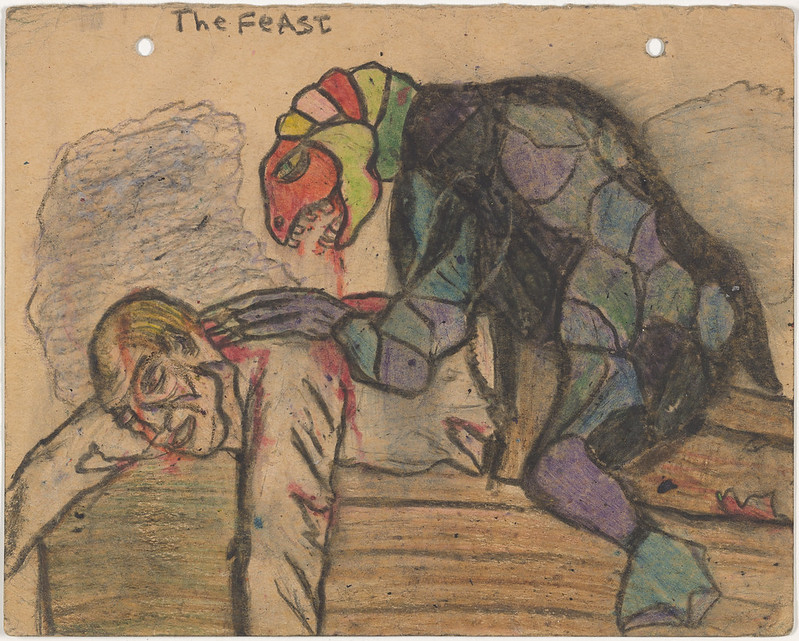

The Lurking Fear  The Feast

The Feast  The Whisperer in the Darkness

The Whisperer in the Darkness  Yagath

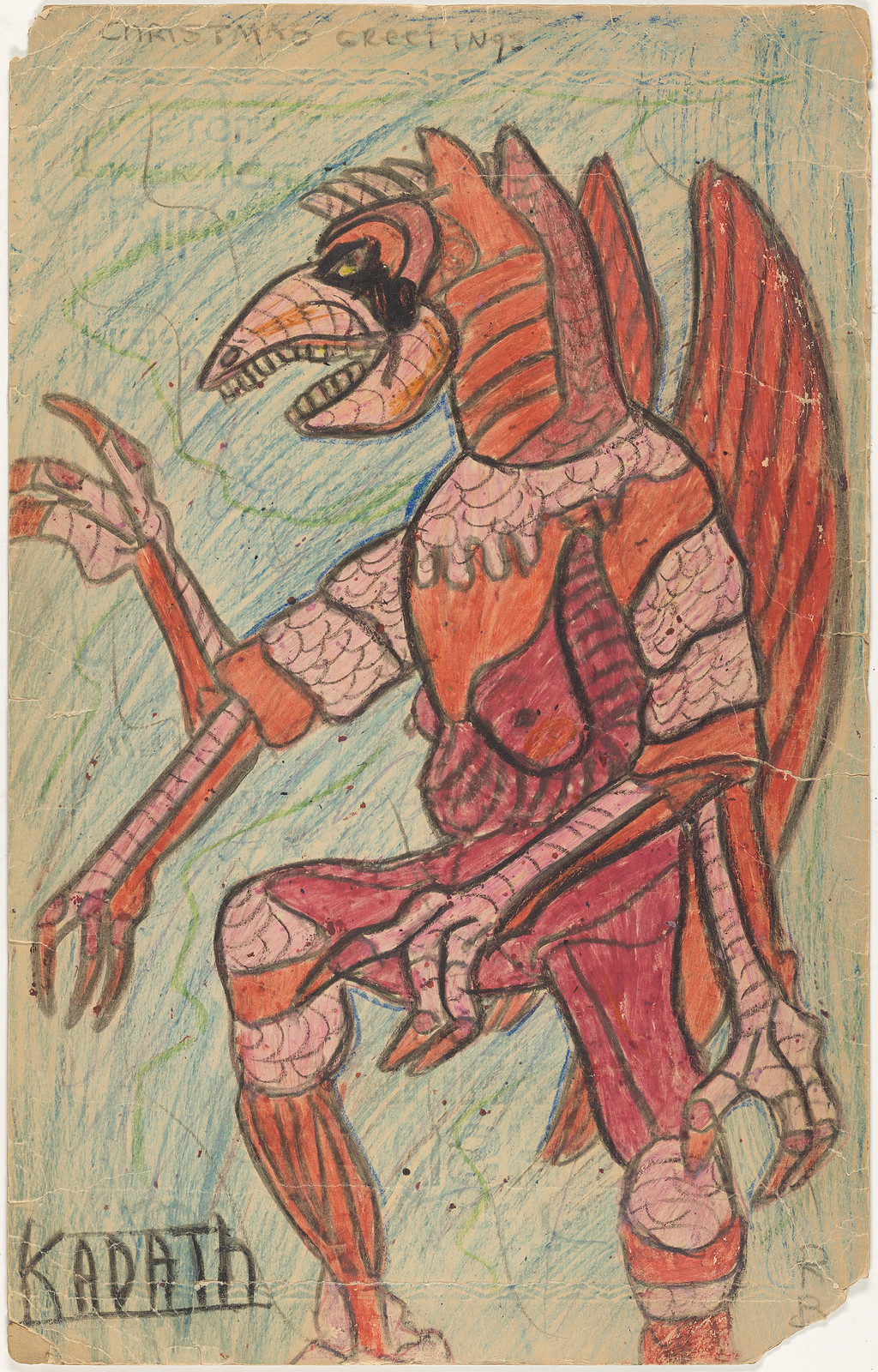

Yagath  Kadath

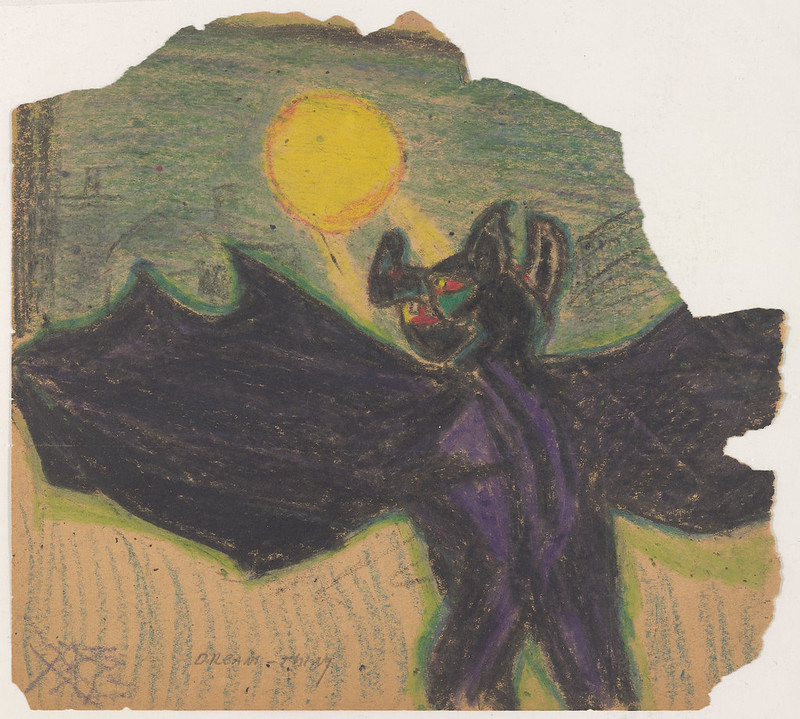

Kadath  Dream-Thing

Dream-Thing  IÄA. Shub-Niggurath Y'A

IÄA. Shub-Niggurath Y'A "During the 1930s, Bloch was an avid reader of the pulp magazine Weird Tales. H. P. Lovecraft, a frequent contributor to that magazine, became one of his favorite writers. As a teenager, Bloch befriended and corresponded with Lovecraft, who gave the promising youngster advice on his own fiction-writing efforts.[1] Bloch's first professional sales, at the age of just seventeen, were to Weird Tales with the short stories "The Feast in the Abbey" and "The Secret in the Tomb". Bloch's early stories were strongly influenced by Lovecraft, and a number of his stories were set in, and extended, the world of Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. It was Bloch who invented, for example, the oft-cited Mythos texts De Vermis Mysteriis and Cultes des Goules. The young Bloch even appears, thinly disguised, as the character "Robert Blake" in Lovecraft's story "The Haunter of the Dark", which is dedicated to Bloch. In this story, Lovecraft kills off the Bloch character, repaying a courtesy Bloch paid Lovecraft with his tale "The Shambler from the Stars", in which the Lovecraft-inspired figure dies; the story goes so far as to use Bloch's then-current street address in Milwaukee. (Bloch even had a signed certificate from Lovecraft [and some of his creations] giving Bloch permission to kill Lovecraft off in a story.) Bloch later wrote a third tale, "The Shadow From the Steeple", picking up where "The Haunter of the Dark" finished. After Lovecraft's death in 1937, Bloch continued writing for Weird Tales, where he became one of its most popular authors. He also began contributing to other pulps, such as the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories. He gradually evolved away from Lovecraftian imitations towards a unique style of his own. One of the first distinctly "Blochian" stories was "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper", which was published in Weird Tales in 1943. The story was Bloch's take on the Jack the Ripper legend, and was filled out with more genuine factual details of the case than many other fictional treatments.[2] Bloch followed up this story with a number of others in a similar vein dealing with half-historic, half-legendary figures such as the Man in the Iron Mask ("Iron Mask", 1944), the Marquis de Sade ("The Skull of the Marquis de Sade", 1945) and Lizzie Borden ("Lizzie Borden Took an Axe...", 1946)." - quote source

Artworks found at the Brown University Library.

Another artwork from Robert Bloch was previously shared here.

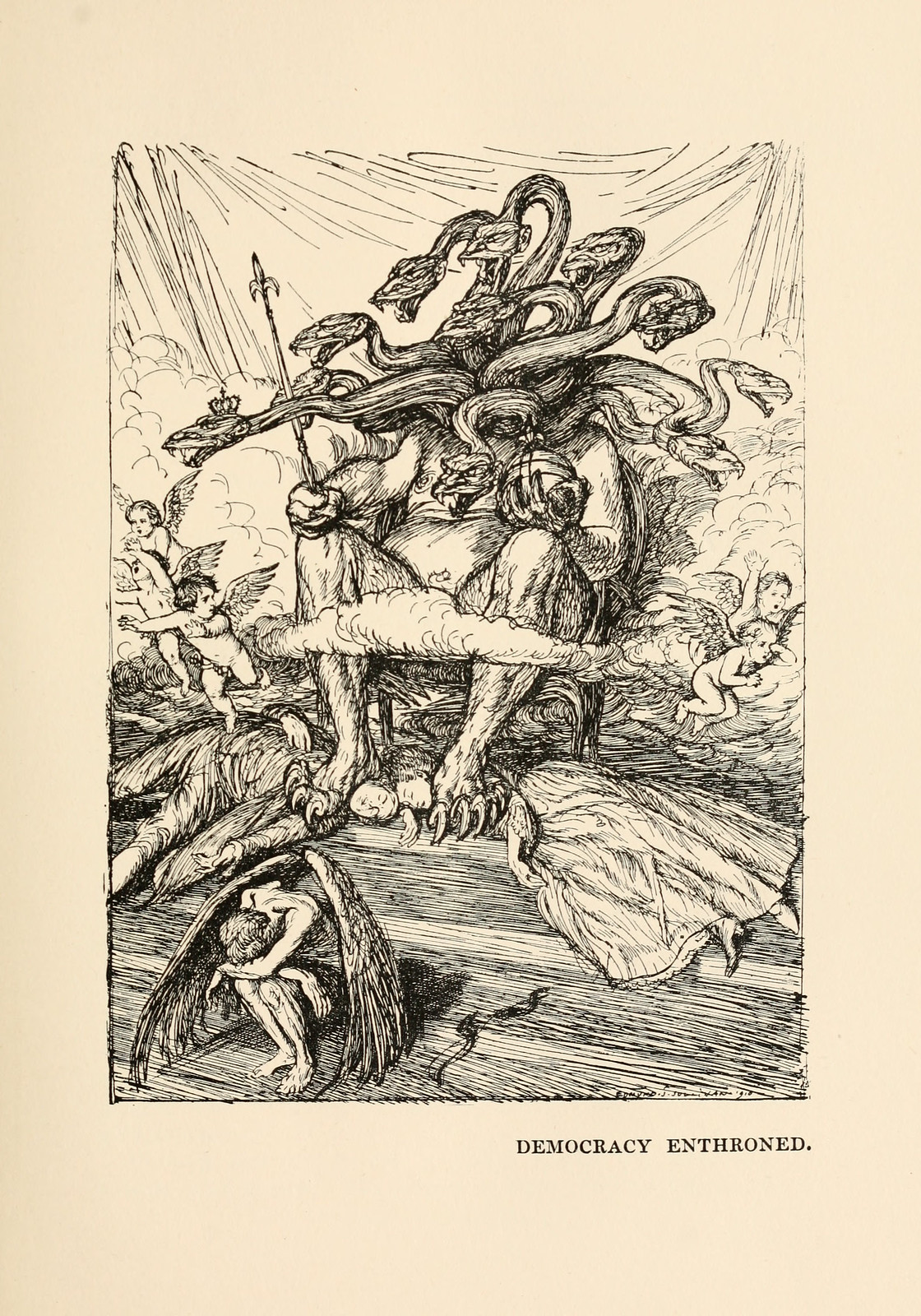

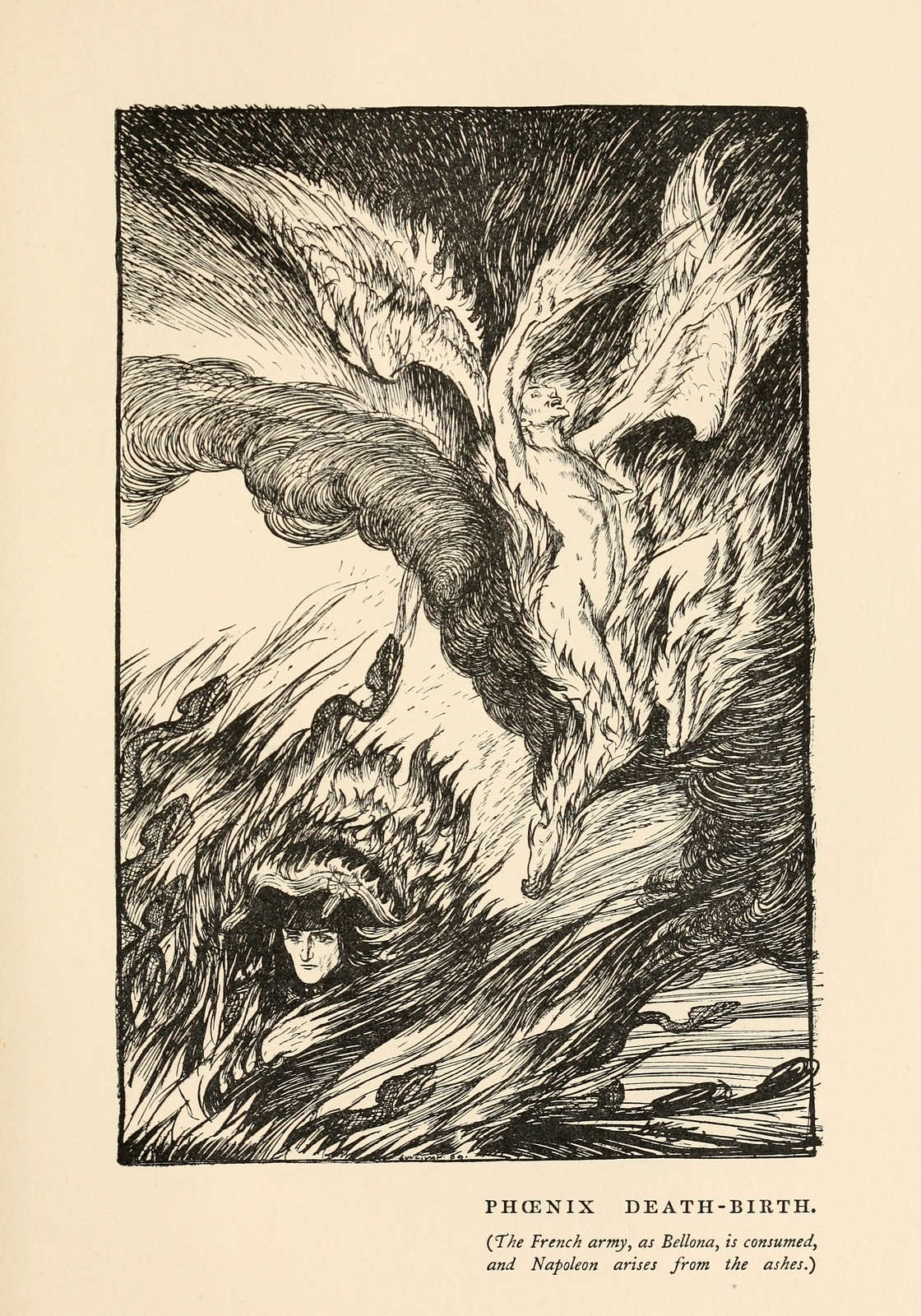

Edmund Joseph Sullivan - Illustrations from Thomas Carlyle's "The French Revolution" 1910

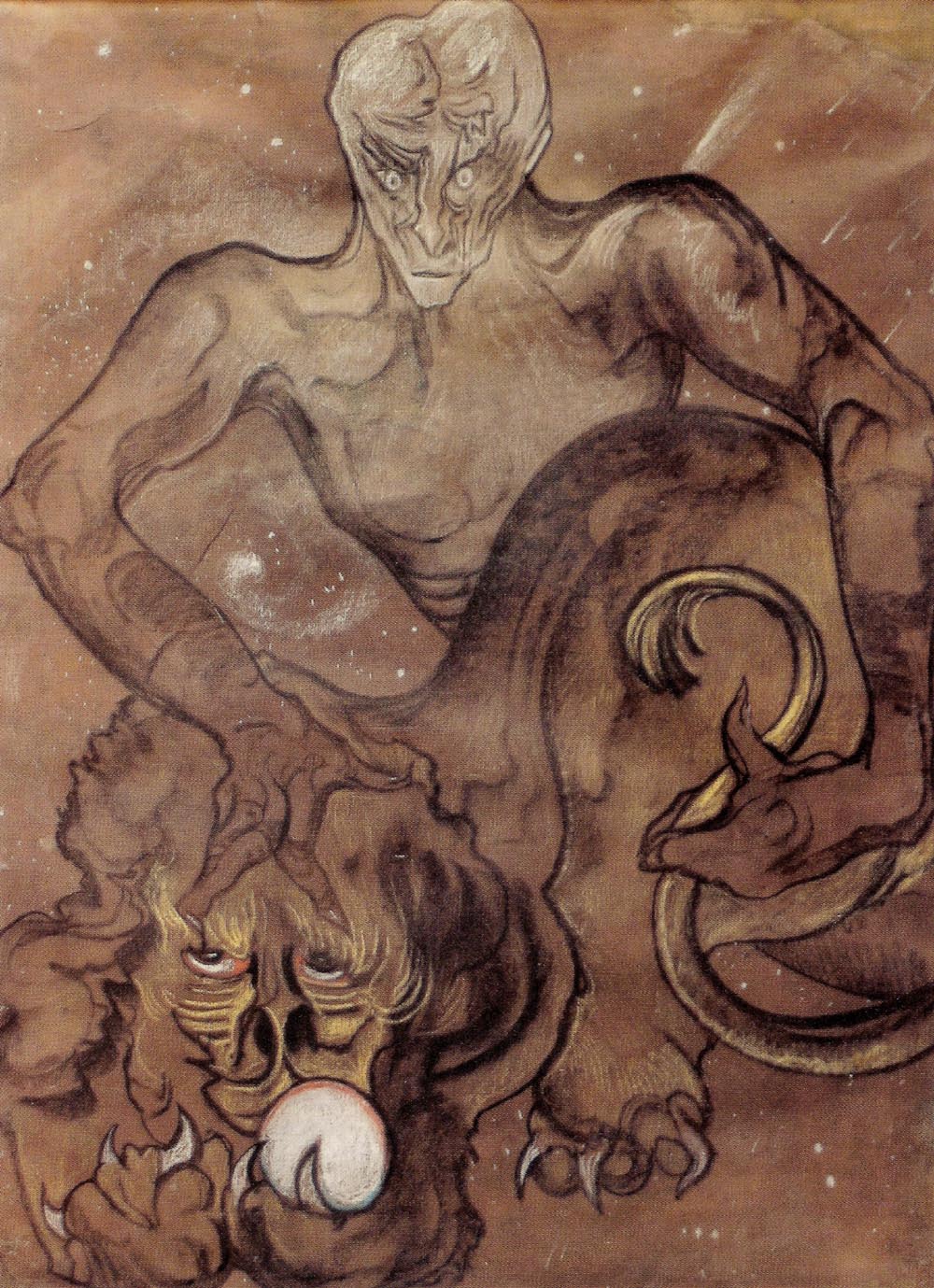

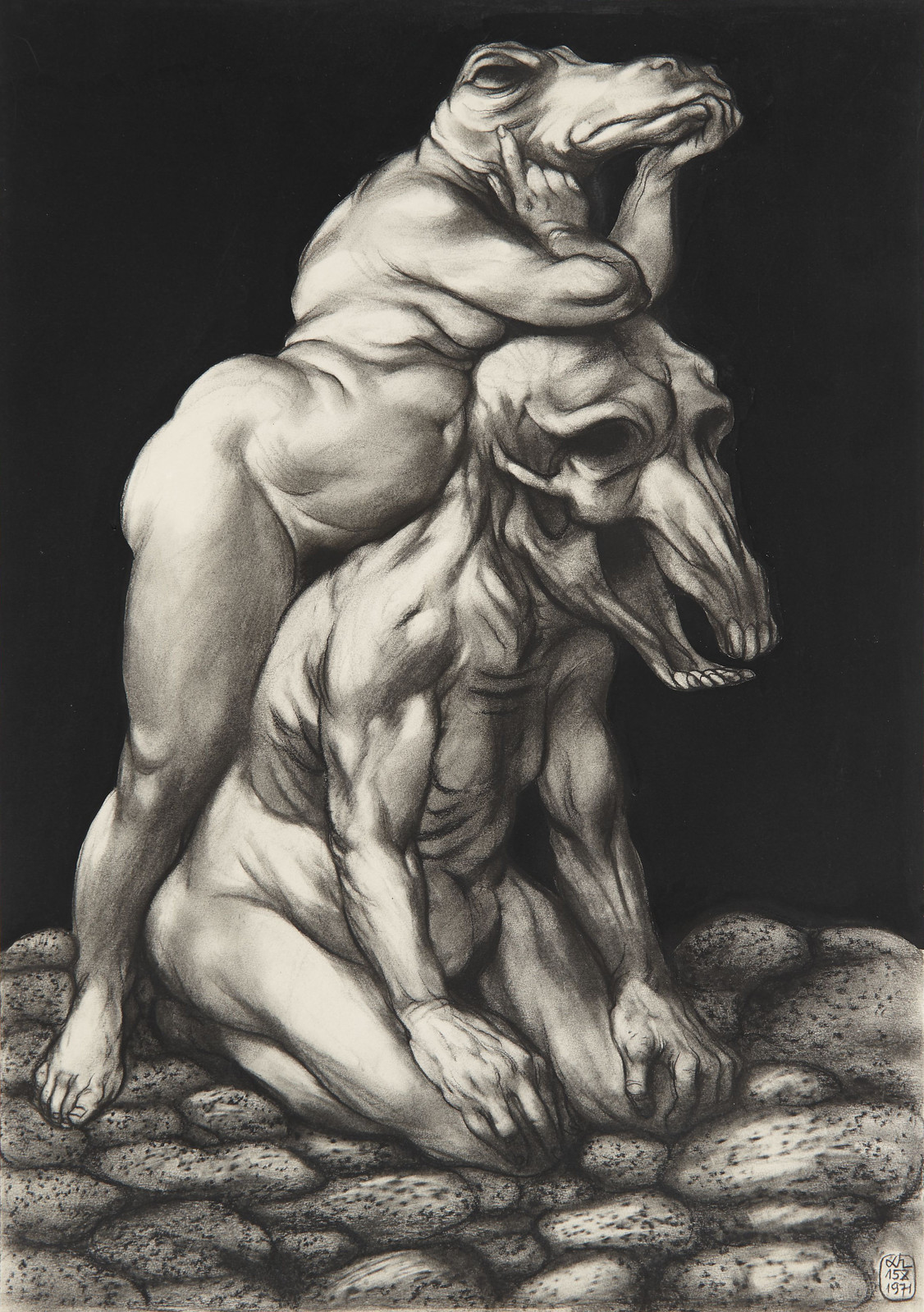

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885 - 1939)

Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Arsenic (from the cycle of chemical compositions)

Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Arsenic (from the cycle of chemical compositions)

Fantastic Composition (Vision with masks), 1920

Fantastic Composition (Vision with masks), 1920

Marysia and Burek in Ceylon, 1920-21

Marysia and Burek in Ceylon, 1920-21

"A struggle between nonsensical and indescribable things. A row of chambers turned into an underground circus. Strange beasts appeared in the loges. The crowd was a mixed bag, an audience half-animal, half-human. The loges turned into bathtubs, connected to urinals in the Mexican or Aztec style. A sense at times of two layers of visibility: the images in the depths were chiefly black and white, while the background had putrid red and dirty lemon-yellow diagonal stripes. The majority of the visions had beasts of land and sea and horrible human faces. Giraffes whose necks and heads turned into snakes growing out of their bodies. A ram with a flamingo nose hung with pink guts. Indian cobras slithered out of the ram, then the whole thing crumbled into a mass of snakes." - quote excerpt from the artist describing tripping on peyote, read more here.

"Shortly after Poland was invaded by Germany in September 1939, Witkiewicz escaped with his young lover Czesława to the rural frontier town of Jeziory, in what was then eastern Poland. After hearing the news of the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939, Witkacy committed suicide on 18 September by taking a drug overdose and trying to slit his wrists. He convinced Czesława to attempt suicide with him by consuming Luminal, but she survived. The film Mystification 2010, written and directed by Jacek Koprowicz proposed that Witkiewicz faked his own death and lived secretly in Poland until 1968." - quote from biography on the artist found at Wikipedia.

Nika Goltz (1925–2012)

Illustration from "The Snow Queen"

Illustration from "The Snow Queen"  Illustration from "The Little Witch"

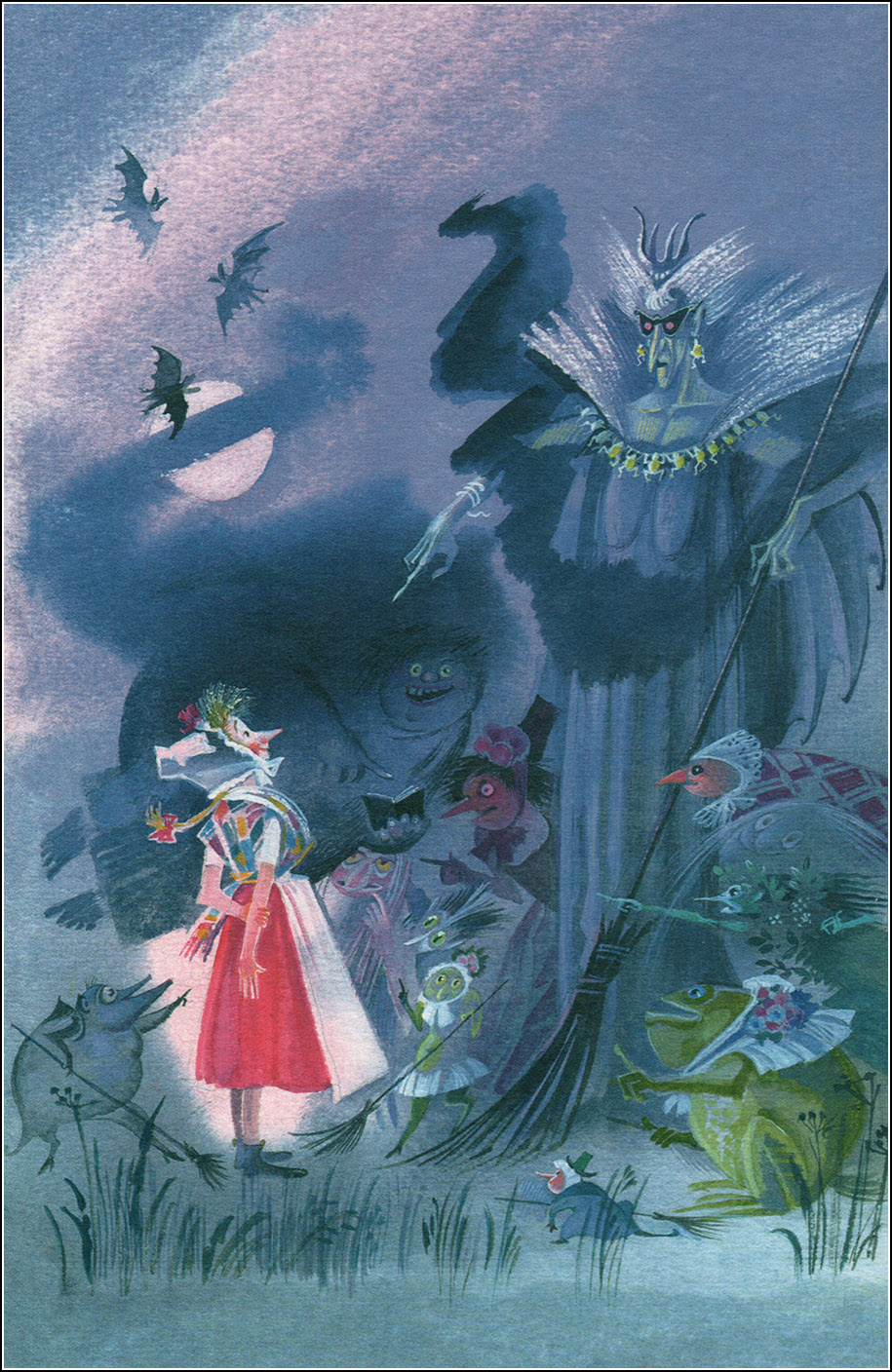

Illustration from "The Little Witch"  Illustration from Alexander Sharov's "Wizards Come to the People" The book about Fairy Tales and Storytellers.

Illustration from Alexander Sharov's "Wizards Come to the People" The book about Fairy Tales and Storytellers.  Illustration from Otfried Preussler's "The Little Water-Sprite"

Illustration from Otfried Preussler's "The Little Water-Sprite"

Illustrations from "English Folk Tales"

Illustrations from "English Folk Tales"

Illustrations from Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid"

Illustrations from Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid"

Illustrations from "Scottish Folk Tales and Legends"

Illustrations from "Scottish Folk Tales and Legends"

Illustrations from Otfried Preußler's "The Little Ghost"

Illustrations from Otfried Preußler's "The Little Ghost"Most artworks found at Book Graphics.

Artist previously shared here.

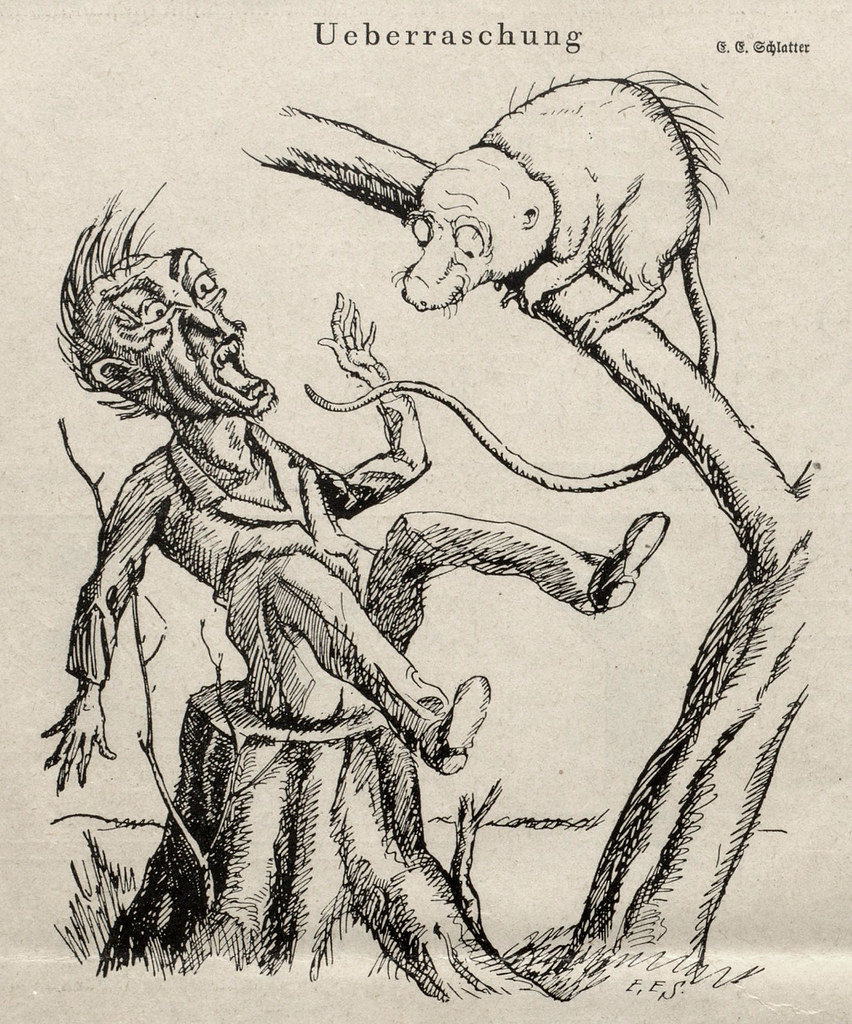

Ernst Emil Schlatter (1883 - 1954)

The Great Horror - Nebelspalter, 1924

The Great Horror - Nebelspalter, 1924

The New Teachings - Nebelspalter, 1922

The New Teachings - Nebelspalter, 1922

Message From Far Away - Nebelspalter, 1922

Message From Far Away - Nebelspalter, 1922

Education - Nebelspalter, 1923

Education - Nebelspalter, 1923

The Frightened - Nebelspalter, 1920's

The Frightened - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Court Session - Nebelspalter, 1924

Court Session - Nebelspalter, 1924

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1923

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1923

Internalized Walk - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Internalized Walk - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Pursuit - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Pursuit - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Indoctrination - Nebelspalter, 1923

Indoctrination - Nebelspalter, 1923

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1924

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1924

Penitential Sermon - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Penitential Sermon - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Artworks originally published in Swiss humor magazine "Nebelspalter" from the 1920's.

Richard Taylor (1902 - 70) - The Document

"Although Taylor is most known for his gag cartoons which poked fun at society, and humorous illustrations for a variety of books (Fractured French, My Husband Keeps Telling Me To Go To Hell, Half a Dollar Is Better Than None etc), it seems his private passion–and one he would pursue til late in life without seeking commercial benefit–was fantasy art. Taylor created a fantasy world called Frodokom, in which he based an entire series of watercolor, print and oil paintings that featured surrealistic creatures and landscapes. Maurice Horn’s Encyclopedia of Cartooning says of Taylor’s work “There is an individuality to his large-eyed, heavy lidded characters that makes one think of fairy tales and other worlds…” In the mid 1930s, he created 40 illustrations for Worm’s End, an adult fantasy book by Lionel Reed." - quote source.

Artwork found at Heritage Auctions.

A selection of Arkham House book covers by Taylor were previously shared here.

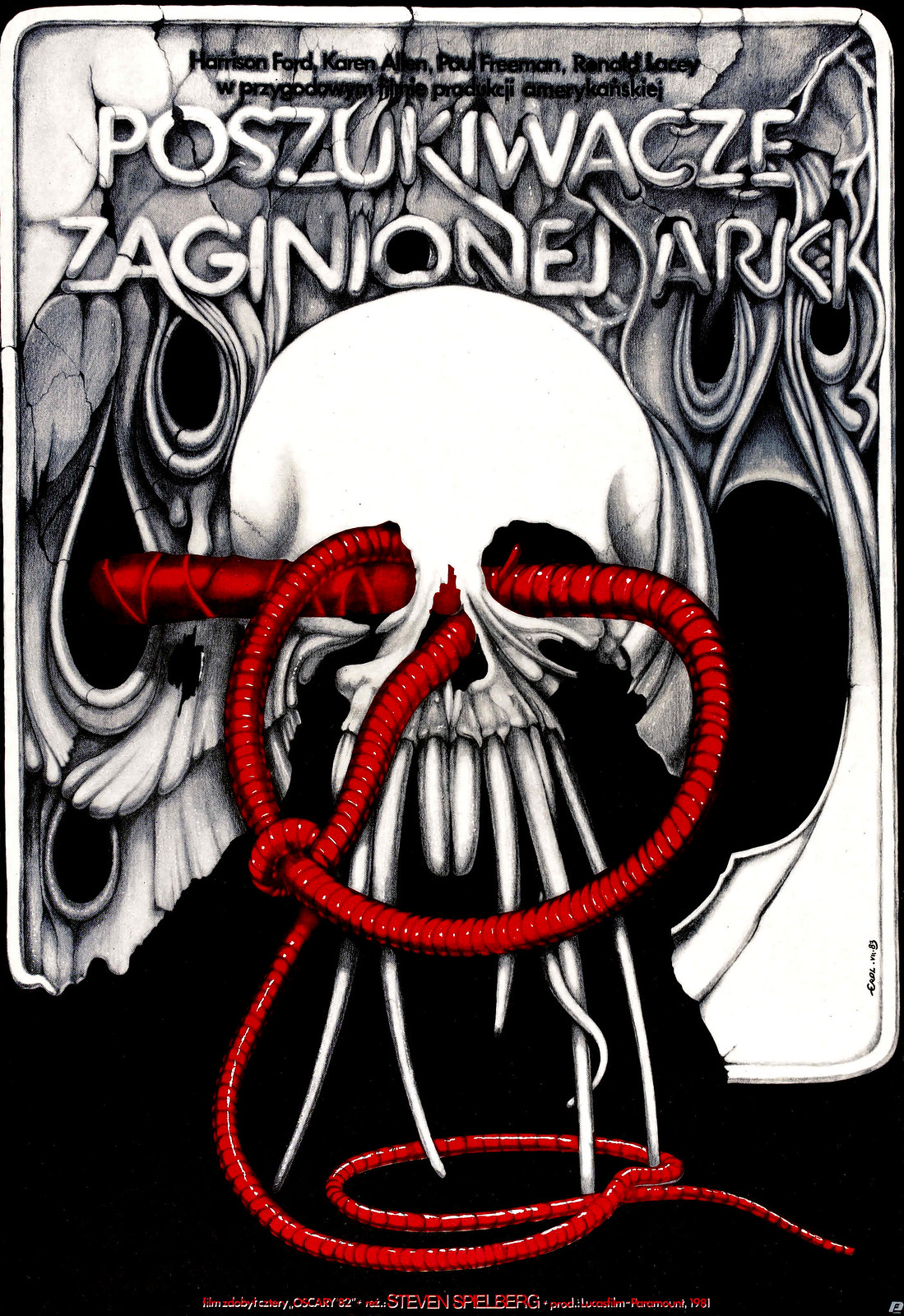

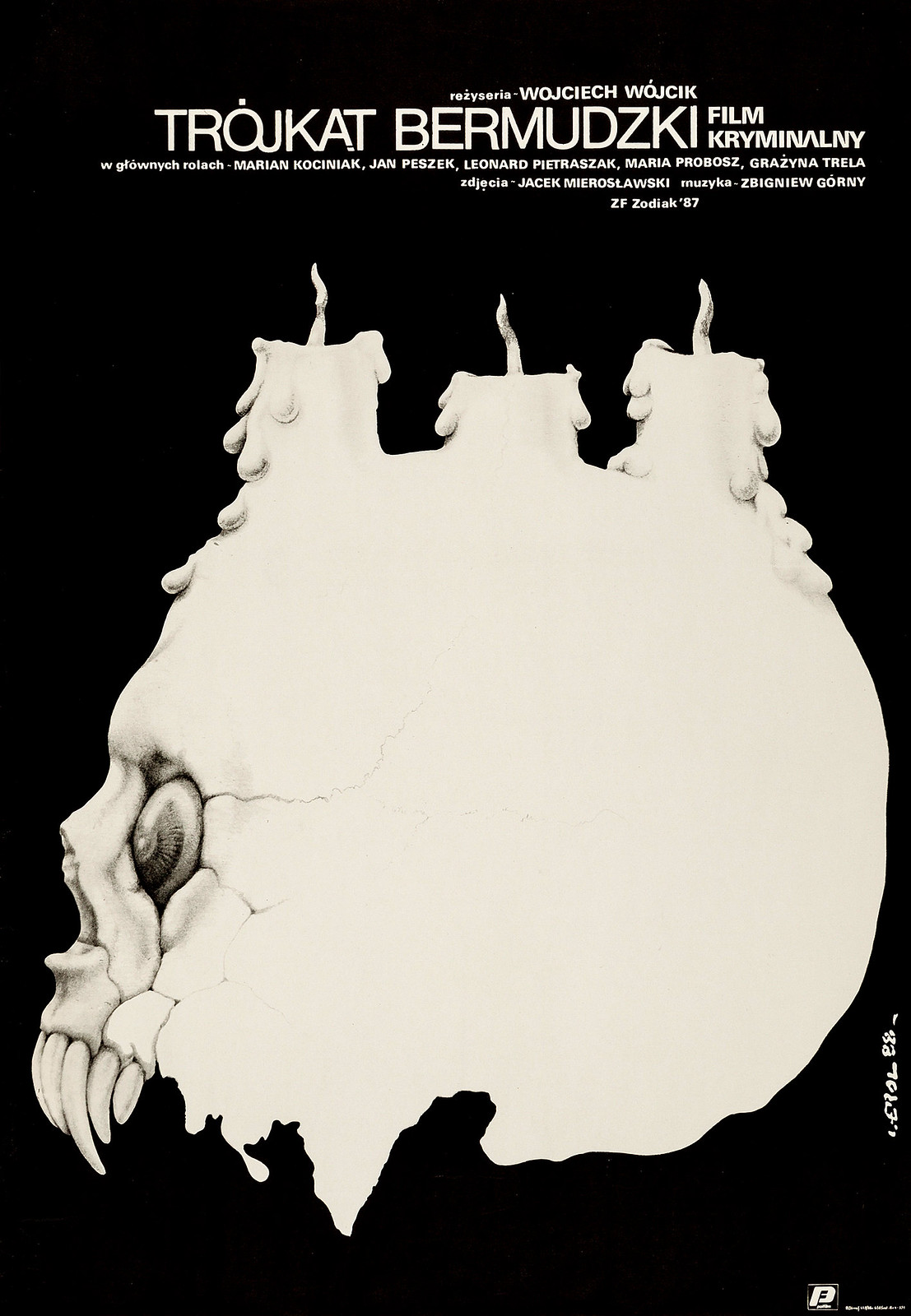

Jakub Erol (1941 - 2018) Polish Film Posters

Adam Hoffmann (1918 - 2001)

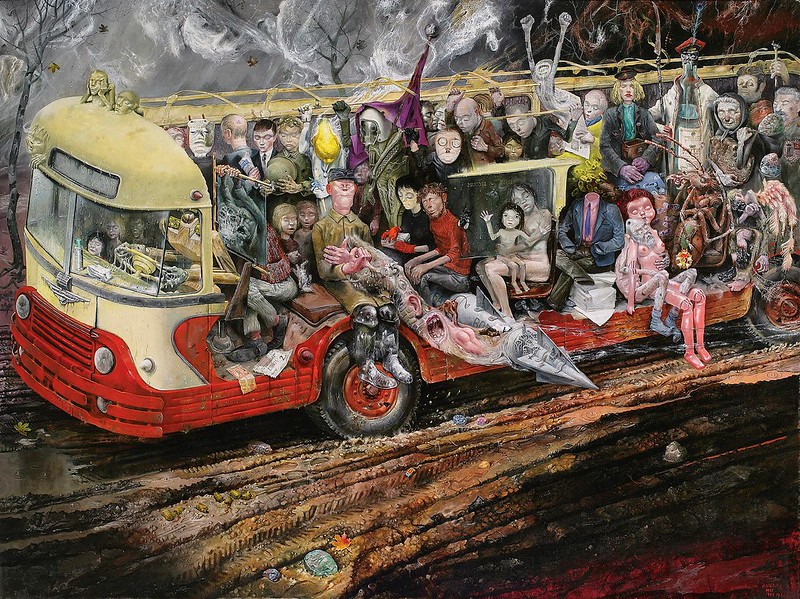

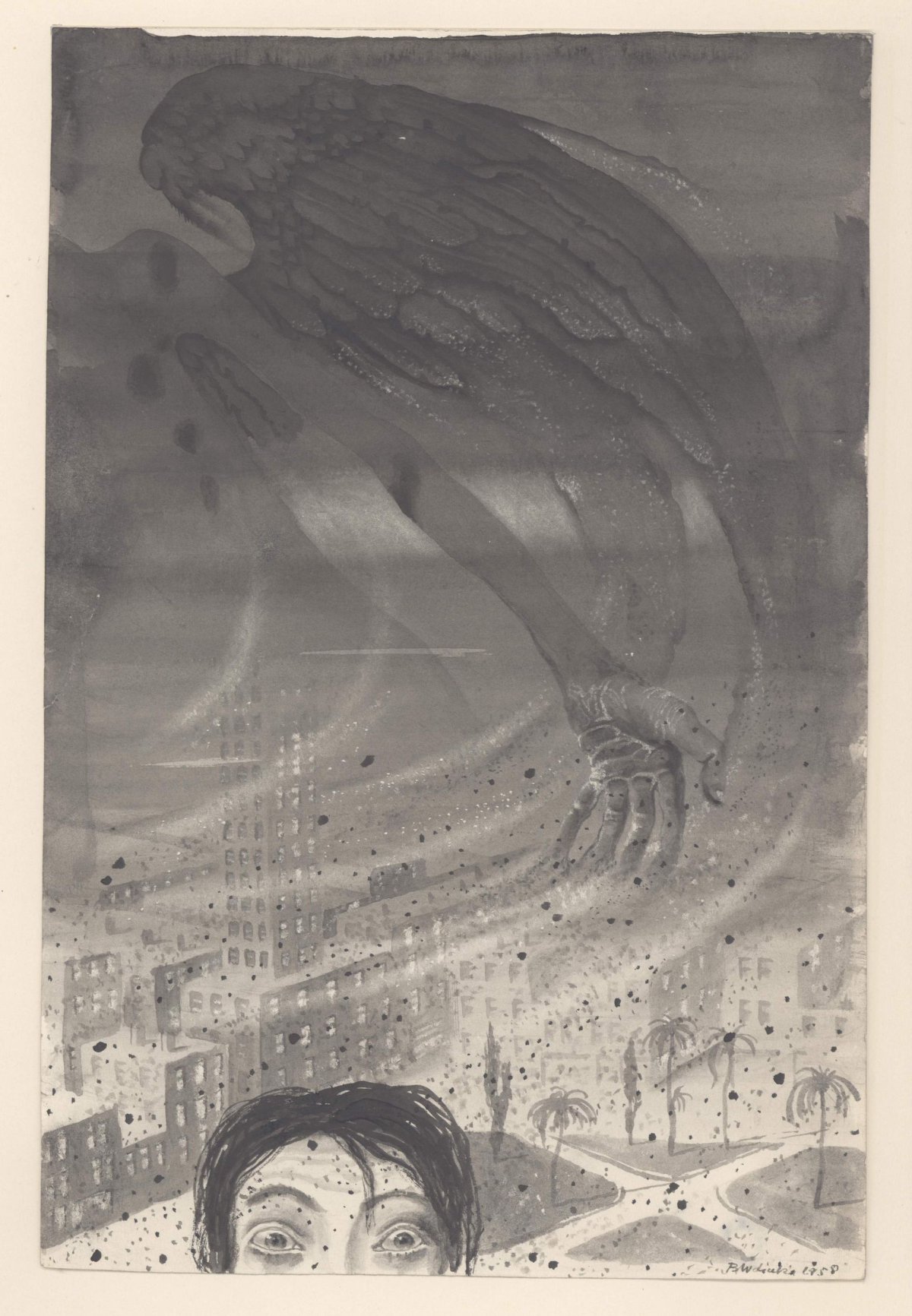

Bronisław Wojciech Linke (1906 - 1962)

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

A biography on the artist's life can be found here.