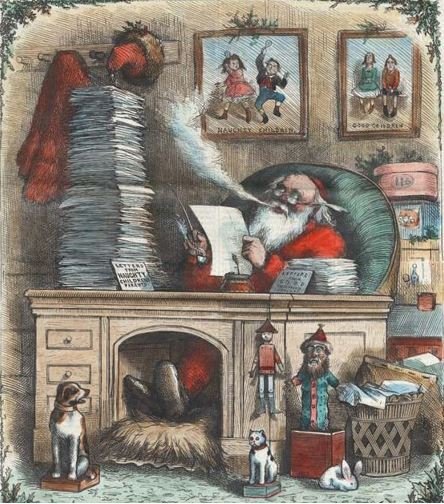

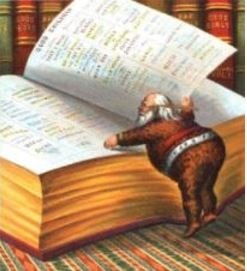

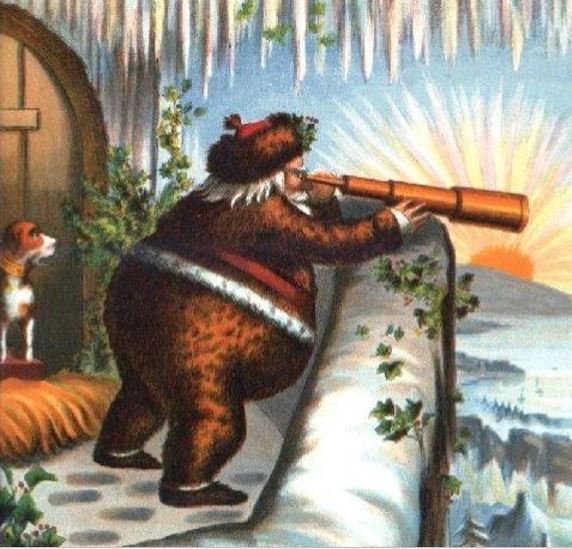

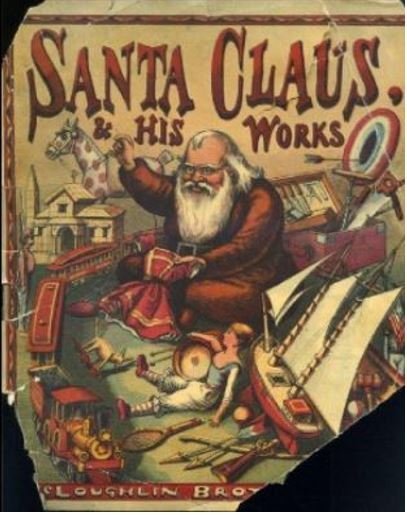

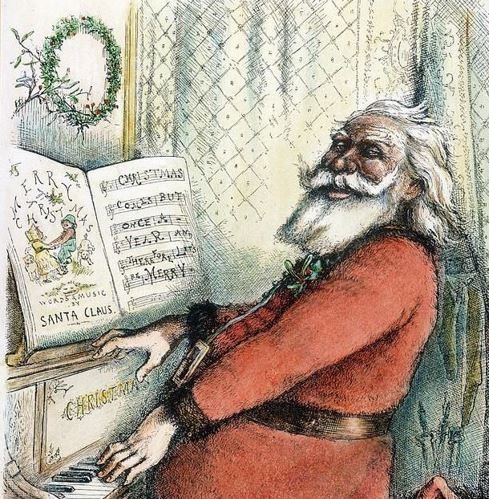

You probably know that Thomas Nash is very much behind the main features of the American Christmas experience. He is the reason we Americans generally don't do plum puddings, wassails, crackers, mumming, christmas plays, etc that were in vogue in some US cities after Dicken's popularized them. Nash was a German immigrant, and his art brought American Christmasses their trees, stockings, gingerbread, reindeer, Santa Clauses, and Sugar Plums (a slangy term for any shiney first class trinket or confection) this art might have remained a New York regional affair had the Civil War not brought those New York periodicals by Railroad to the military camps all around the country, where local and military newspapers often shamelessly pirated the images, increasing their ubiquity. Not that these concepts were entirely new, a century of "dutch" immigration (dutch being a term applied to all german and east european newcomers) had planted some colonies in diverse places like Alexandria Louisiana, St. Louis Mo., Richmond Virginia, Chicago NY, and California. And the old european traditions were already working into midwinter revels. But the threads of Christmas were still woven mostly of the Colonial midnight bonfires, random fusilades of gunfire into the air, fireworks, pumpkin pudding, roasting chestnuts, ice skating balls, and heavy drinking. Strangely enough Christmas was actually outlawed in the old puritan regions...such as Massachusetts, and would stay that way until Reconstruction, when Republican politics pushed it hard as a reconciliation measure for the whole reunited Republic. The Dickensonian Christmas with it's methodist humanist concentration on piety, gratitude, service, charity, and English tradition was a new thing only recently overcoming the prejudices and resentments of post War of 1812 America, but eagerly adopted in the Southern "section" especially.(as might be expected in the 1840-1860 era because cultural and commercial ties between Big Cotton and John Bull were very strong, while the industrialists and capitalists of the North (many doubly anti-english Scotsmen) were in stiff and angry competition with English manufactures and tariffs.

In many ways Southerners were more likely to celebrate Christmas than Northerners in 1860. For instance the otherwise religious New Bedford Whaleships didn't even offer a tot of grog, nor any other recognition of so "Romish" a holiday, despite the crews being the most heterogeneous bunch of jack tars imaginable.

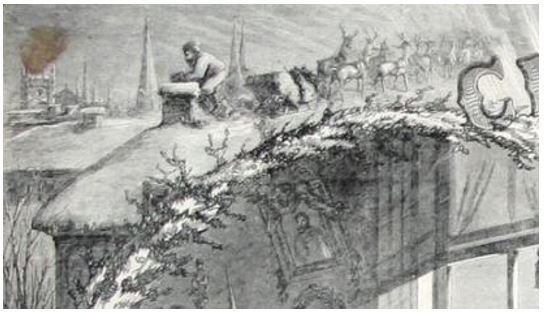

So it was war, the terrors and miseries thereof that sought some solace as loved ones pined for one another, or wept over vacant chairs, and the cultural vogue for Romantic maudlin emotion craved an outlet that latched onto the magical elf that could reach over distance and bring gifts, love, sentiment, and cheer from the hearth of home to the cold damp campaign tents of the camps, effected by the military Post, the railroads, and even the first illustrated post cards (forerunners of Christmas cards) in both North and South the war blended the cold piety of the Religious Observance damping the exubrant fire of Boozy colonial excess, and lifting the winsome wistfulness of Coming Home to some warm emotional embrace of loved ones.