It is 1979. Those that find themselves not fitting into ordinary society, feeling like an outsider, or being rejected because they do not fit the norms in terms of gender, sexuality, and identity have the need to escape, to find a place not only where they will fit in, but where they are also the norm. Not easy in this day and age, when to be gay or lesbian or transgendered is reason enough to be despised and decried, to be regarded as monstrous or perverse. There is, though, such a place. Isolated and on the edge of America as far from middle America—both geographically and figuratively—as you can get. This is Roseville Beach. Located on a barrier island just a short ferry ride off the coast of the North American Atlantic or Gulf Coast, this is a community where ‘queer’ is the norm. Where visitors come because it is accepted and those that stay do so because they find acceptance and a family that they create for who they are. A family that they also have to rely upon, for the authorities and particularly the police rarely bother with Roseville Beach—and if they did, it would not be to the benefit of anyone within the community. Thus, if the ‘queerdom’ of Roseville Beach have an issue, it is they who sort it out, but it is not just because they are queer that see to their own and prefer to deal with their own problems, for the community of Roseville Beach has other secrets. As much as it is a haven for ‘queerdom’, it is also a haven for magic and the supernatural, for the witch and the wizard, for the shapechanger, for the familiar without a mistress or master, for secret societies and cabals. They are not the norm within Roseville Beach, but they are known, and there are members of the town’s ‘queerdom’ who have gifts and magics themselves and will use it to investigate the strange and the supernatural, the mysterious and the magical, all to keep the community safe and avoid the undue attentions of the authorities on the mainland.

This is the set-up for

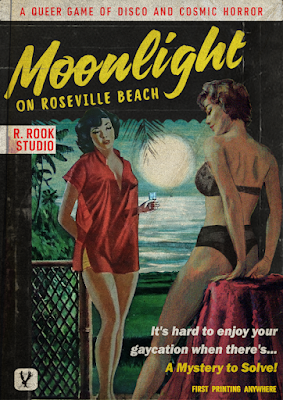

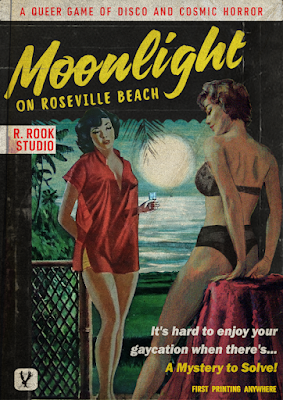

Moonlight on Roseville Beach: A Queer Game of Disco & Cosmic Horror, an urban fantasy roleplaying game in which the Player Characters are part of both communities in Roseville Beach and thus outsiders twice over. Published by

R Rook Studio following a successful

Kickstarter campaign, this is a storytelling roleplaying game of magic and mystery, community and care, and of family and fear. This is very much a roleplaying game for mature and accepting players, for it is set in a town where the majority of the population is LGBTQIA+ and it is explicit about this—though that does not mean that the roleplaying game is either explicit or exploitative in other ways. In other words, it is explicit in its social acceptance of LGBTQIA+ being the norm. However, there are issues attached to this. One is that it is not obviously accepting of all norms when it comes to people of colour. This is not to say that they are not present in the setting of Roseville Beach, but rather they are not depicted as being present in the roleplaying game’s artwork. This is because the artwork is public domain, all taken from LGBTQIA+ pulp novels and whilst thematically appropriate, the characters, luridly, suggestively depicted, are all Caucasian. The book does acknowledge that this is an issue, one caused by the artwork rather by intent. Another issue is with the term ‘queer’. The author uses it as a catchall to describe all members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and whilst it is period appropriate, it was used as a slur. It is not the intent of the author to use it in the pejorative sense, but there are members of the LGBTQIA+ community who may see it as an insult. Thus, as part of her Session Zero of

Moonlight on Roseville Beach, the Game Master may want to discuss what is an appropriate term to use in her game.

A Player Character in Roseville Beach has an Origin which Provides a Background and Skills, as possible Troubles. They will also have a Job which provides a further Skill, a Strange Event that they had, plus Allies and Comforts. There are six Origins and each grants a special ability. The Fresh Face is the new kid who has fled his family to find out who he is in Roseville Beach and has the ‘Beginner’s Luck’ ability to let his player reroll ones when undertaking an action. The Scandalous has fled to Roseville Beach to avoid media attention and gains an extra contact, though it may not be one that the Player Character wants. Both the Fresh Face and the Scandalous have more Backgrounds and Skills than the other Origins. The Shifter can shift into an animal form and back again, and has two banes that force him into his animal form. The Witch has the Witch Background and Sorcery Skill and also knows three Words of Power that fuel his magic. The Familiar was once attached to a sorcerer, but no longer is, so knows a lot of magic and Words of Power, but is stuck in his animal form and must communicate telepathically and needs help to perform magic. Plus of course, the Familiar does not have a Job. The Stranger has come from somewhere else, and knows a little bit of magic, some of it innate, and has worked hard to acclimatise himself to the world of men. The Strange Event is shared between two players and their characters, such ‘The Monolith’, which seemed to follow them both, but was never seen to move, or ‘The Starry Form in the Dunes’, a glimmering figure seen in the dunes west of town one night which called something to either Player Character. The Strange Event can leave the Player Character with an extra Skill, an Ally, or Word of Power, or a Scare, a Trouble, or even an Injury. Besides an Ally, the three Comforts a Player Character has are a ‘Special Place’, a ‘Special Memento’, and a ‘Special Person’. During downtime, spending time with a Comfort can help to remove a Scare. Lastly, the Player Characters share a Bungalow. This is used as both a base of operations and a potential source of supplies, although that does not necessarily mean guns. Certainly, the Player Characters do not have ready access to guns and their use can lead to a Player Character suffering a Scare.

To create a character, a player selects an Origin and chooses his character’s Comforts and Allies. He then rolls for a Background, Skills, Troubles, Scandals, Words of Power, and so on as appropriate. Then the players establish the Strange Event between their characters and determine its effect.

Lana Jorgeson

Origins: The Witch

Age: 24

Backgrounds: Witch, Magic Shop

Skills: Sorcery, First Aid, Stagecraft, Charming

Job: Piano Player at Cedar Point Hotel

Words of Power: Flood, Bless, Heal

Troubles: Someone in Roseville Beach helped set me up with somewhere to live, a job, and some money.

People I Owe: Jon Amos

Ally: Ghost in the Bungalow

Strange Element: The Poltergeist

Comforts: Special Place – Violet Flame Candles &Gifts, Special Memento – Grandmother’s locket, Special Person – Mrs Esther Neilson (Oblivious Grandma)

Mechanically,

Moonlight on Roseville Beach: A Queer Game of Disco & Cosmic Horror uses dice pools of six-sided dice, rolled whenever a Player Character undertakes a Risky Action. To assemble a dice pool, a player starts with a single die and adds further dice for relevant Backgrounds, Skills, for the situation being a Golden Opportunity, and if the Player Character is protecting a housemate, ally, and so on. These are all rolled with the aim being to roll as high as is possible on each die. No matter the results, they are then assigned individually to different tables. The standard set of tables are ‘Goal’, ‘Injured’, ‘Scared’, ‘Clue’, and ‘Trouble’. The Game Master decides which tables come into play, depending upon the situation and what the Player Character is trying to do. ‘Goal’ is the base table, but if the Player Character is investigating something, the Game Master will add the ‘Clue’ table, and if there is a chance of the Player Character being injured or scared as result of his actions, those tables are added to. The ‘Trouble’ table is added if the player has not rolled enough high results and wants to roll an extra die. However, it places an Ally, Trouble, or Comfort in danger. If the player does not have enough dice to assign to the tables the Game Master has set out, he either decides to approach the situation in another way to reduce the number of tables, or if he rolls, any tables without dice are counted as if ones are assigned to them—which is not good. In general, results of four or more on all of the tables bar the ‘Trouble’ table indicate progress or a positive outcome, but it is always the player who decides where the dice are placed and thus decides on the degree of success or failure for the action.

Magic uses the same mechanics. The Player Character must be a Witch, Familiar, or Stranger, possess the Sorcery skill, knows one or more appropriate Words of Power, and can gain more dice for taking time, having someone with the Sorcery spell help, using a spell book, casting the spell at an auspicious time, and so on. Magic always involves the ‘Scare’ table and always adds a table of its own which determines if control of the magic is lost.

For example, Lana has been lured to the house of a local dignitary after a strange magical encounter only to discover what she thinks is ritual that will see her mind supplanted by the dignitary’s. The dignitary’s aide, Georgina Wellman, has a revolver, a Saturday night special pointed at Lana in order to persuade her to co-operate. It is approaching midnight when the ritual needs to be performed and Lana, not liking the odds either way, decides upon a brute force solution. She will cast a spell using the ‘Flood’ Word of Power, drawing from the swimming pool outside the house, the aim being to disarm Georgina, disrupt the ritual, and cause chaos. Her player assembles the dice pool, beginning with the base, plus one each for the Witch Background, the Sorcery Skill, and the Game Master allows an extra die because it is an auspicious moment or midnight. That gives the player four dice to roll.

The Game Master lays out the tables that the player will be assigning dice too. These are ‘Goal’, ‘Injured’, ‘Scared’, and ‘Magic’. The player rolls two, three, five, and six. He assigns the six to the ‘Goal’ table, which means it is achieved and the five to the ‘Magic’ table, which means that Lana does not lose control of the magic. The two and three are assigned to the ‘Scared’ and the ‘Injured’ tables, meaning that either Lana or an ally is injured, and everyone is scared. The Game Master narrates how the water from the pool surges up and in through the window of the house and swirls around the room that Lana and Georgina are in. Both are knocked to the floor and bruised and battered as the furniture is shifted. The gun is knocked from Georgina’s hand and everyone screams in terror!

Moonlight on Roseville Beach is thus mechanically quite simple and has two consequences. The first is that the Game Master will need to place the various results tables on the table before the players so that they can consult them and make choices. The second is that the players can make these choices. They determine the degree of outcome, which the Game Master narrates.

One odd addition is a set of Guest Stars that allow other players to step in and participate in a mystery on an occasional basis. Alternatively, these could be used as NPCs, but either way they include an interventive cast of characters, such as ‘The Haunted Ice Cream Vendor’, ‘Definitely Not An Occultist’, and ‘The Oblivious Grandma’, amusingly unaware of anything out of the ordinary going on in Roseville, either in terms of the LGBTQIA+ community or the outré. These are fantastically well-drawn characters, ones that contrast sharply with the standard types that the players roleplay, so that if the roleplaying game were being run as if it were a television series, they could potentially make highly memorable appearances. They could even be used as potential scenario ideas. For the Game Master, there is deeper background on the various locations in and around Roseville Beach, including a hotel whose young owner is missing, a rocky island occupied by overly curious otters, of bronze monoliths that are never seen to move, but clearly do, and more. These locations do come with hooks, some more detailed than others. There are threats discussed here too, some of which does involve the bigotry of the era. There is advice on setting up a mystery, giving out clues, and handling romance. The advice for the latter is nicely done and provides advice for relations between Player Characters and NPCs and between Player Characters. There are also several ready-to-play scenarios as well.

Physically,

Moonlight on Roseville Beach: A Queer Game of Disco & Cosmic Horror is fantastically presented in its use of its period book covers and graphical style that luridly hint secrets and truths, of just somethings that are different at the edge of society. The book is also well written and an engaging read.

Moonlight on Roseville Beach: A Queer Game of Disco & Cosmic Horror is a roleplaying game about the othering of minorities and their agency. The othering of minorities is simply and directly handled—it is normalised. Roseville Beach normalises the LGBTQIA+ community in a way which could almost never happen in 1979 when it is set, and makes the Player Characters intrinsically part of it and wanting to be part of it. Then it normalises it by having the players accept and roleplay this norm. In doing so, it gives room to both characters and players to explore and investigate the second othering present in Roseville Beach, that of magic and the supernatural, as well as the agency to do so. The characters within the setting and the players within the mechanics that give them the capacity to decide the outcomes of their characters’ risky actions. It is a powerful combination in terms of storytelling and resolution.

Moonlight on Roseville Beach: A Queer Game of Disco & Cosmic Horror is a fantastic combination of acceptance and community with pulp horror and mystery, that like its setting of Roseville Beach, gives a space for the marginalised and scope to tell their stories as they confront horrors and mysteries, and so protect their new homes and family. This is a great storytelling roleplaying game, good for one-shots and conventions as it is for telling longer summer seasons.