Models & Toys

Gaming Figures from China

These are all very high quality both in terms of the sculpts and the production value.

Publius Goblins

LOD: Greek Mythology Pantheon of the Gods.

TihonFigureN: Dwarves - Axe, Beer, Beard.

Lakeshore Royal Kingdom Adventure Castle

3D Printed Random Figures

3D printing is almost certainly the future for high end figures of all types. It is still fairly expensive to print the figures compared to mass production, but that may change in the coming years. Below are the first 3D printed figures I purchased off of ebay. The are a random assortment of super cool poses. These are in 54mm scale. It would be easy to spend a fortune on these figures. I intend to be very particular about the ones I buy going forward.

Biplant: Elves and Dragonriders.

Back from the Dead!

Photo stolen from a demon.

Photo stolen from a demon.Hello you wonderful people, monsters and other dungeon crawlers. I am back from my long absence.

Around three years ago, I was diagnosed with life changing health issues. Issues for which medical science has no effective treatments. So, my priorities changed and I went on a personal journey of exploration to find alternative treatments and solutions. My path turned a bit dark and eventually drew the attention of law enforcement resulting in a host of criminal charges. My trial was an absolute circus with the prosecution recklessly tossing around terms like "atrocity" and "ritual sacrifice." I fought the good fight in court but the deck was stacked against me. The final result was my sad, and untimely, execution by the State.

Fortunately, my younger brother has a real talent for unspeakable acts of necromancy. This past solstice he pulled me back from my convalescence in the grave. Sure, I had to give him back his soul and his spell makes me cluck like a chicken whenever he says the word "burrito," but that is a small price to pay for a new lease on life. I do mean lease as I must pay the rent every equinox and solstice from now on and eat a very restricted diet, if you know what I mean. At least I was able to get a lot of work done while in the dirt and I will now be able to get back to regular weekly posts for the next several months. I have a lot of new figures to catch up with. I hope you will all enjoy.

Beleriand Toy Soldiers: J. R.R. Tolkien's Children of Hurin.

Beleriand Toy Soldiers of Russia has released a super high quality series of 60mm figure sets based on J.R.R. Tolkien's Children of Hurin. They are among the best figures ever to come out of Russia. They are very expensive ($10-$15 each fig). Sadly, they are made of a very soft material that can distort under pressure. That makes storage a little complicated.

Set #1 Children of Hurin.

Set #2 Orcs.

Set #3 Donath

Set # 3.1 Donath

Set #4 Nargothrond

Set #5 Dorlomin

Set 5.1 Dorlomin.

Set #6 Beren & Luthien

Kool Kelly’s Place: True Confessions of an ’80s Bedroom

Recollections / December 17, 2024

ROBERTS: I can’t believe I let you guys talk me into this, but I suppose it has to be done. A few months ago my dad sent me a whole bunch of pictures on a flash drive. This was one of them. It’s my bedroom in 1987. I’m 15. I think it’s winter: you can see a couple of LPs on the bed—Mad Parade’s A Thousand Words and The Cure’s Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me—that came out in early ’87, but you can also see a Punisher comic (#5) that came out around November (the cover date is January, but comics were future-dated so kids like me didn’t think they were old). Given all the tokens of war and violence in view, it’s somewhat incredible that I didn’t turn out to be crazier than I am. This is Reagan’s America, baby!—Even though I was a staunch Democrat and was already gearing up to pass out Dukakis bumper stickers and buttons at school. You can also see “SKT4 ” and “WAR SUCKS” written on the wall. Was I trying to suggest something about the duality of man? The Jungian thing?

” and “WAR SUCKS” written on the wall. Was I trying to suggest something about the duality of man? The Jungian thing?

I also had a thing for vigilantes, as you can see. Along with the Dark Knight (Frank Miller’s series came out in 1986, changing comics and pop culture forever), Wolverine, and The Punisher, I was an avid Mack Bolan fan (the poster next to the baseball lamp). And all those yellow bags? They’re from Tower Records, which had recently displaced California Comics as my favorite destination. I was either working at the video store at the time or working at the mall (selling personalized children’s books!), or both. You see where the money went, for the most part—my skateboarding gear is not in view. And yeah, that’s a waterbed, suckers! My dad “got a deal.”

Things were about to change, though: I would stop collecting comics within a few months, Bolan would be cast aside for “classic literature,” and all of those posters would come down. We would move soon—in ‘88 or ‘89. I was about to buy my first electric guitar and my first amp. Kool Kelly—bless my dad, who designed and painted that when I was around 10—was going full teen.

I’m pretty sure that my parents took this photo because I was a slob and they wanted formal evidence of that fact. Now the whole world knows.

MCKENNA: What’s that expression you lot over there use to express incredulity? “Hoo boy!”? Well, hoo-fucking-boy! I knew when Kelly announced he had this picture that it would be good, but I presumed it would just be very telling about—and punishingly humiliating for—Kelly. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine it would be an absolutely on-the-nose perfect metaphor factory for a whole fucking country. Because it feels like all of the demented soup that is your great nation is in there. The “War sucks” within five feet of multiple images of people blasting their enemies into oblivion that you’ve mentioned above. The toy submachine gun right next to the panda plushie. The vast inflatable Shamu that looks like it’s being used as the world’s least comfortable pillow. The phone, presumably trailing one of those forty-mile-long cords that you lot love. The weirdly feeble plug sockets. It’s as if someone turned an American Mind inside out.

Where to start? Not with the tissues. We’ll leave the tissues well enough alone. Or with that weird pickled thing in the bell jar. Or the way American beds always seem to look like a cross between a medieval voivode’s funeral catafalque and a dismantled piano. Let’s start with the elephant that is literally in the room: the writing. Mike, you share a nationality with Kelly—what the hell is going on here? And what the hell is a “baseball lamp”?

GRASSO: What’s going on here is the quintessential late-1980s suburban American boy’s materialistic id unleashed. Well, maybe there’s a bit of ego and superego in here as well, let’s be fair. I will say straight off: my bedroom in 1987 wasn’t quite this overloaded with my precious material possessions (that year I was in that awkward edge-of-adolescence period between putting away childish things—my Hasbro universe G.I. Joe/Transformers obsession—and falling head-first into Dungeons & Dragons), but ’87 was the year I discovered comics. I was into Marvel as well, Kelly, but more into the mutant titles like Uncanny X-Men, X-Factor, and New Mutants than Punisher and The Dark Knight Returns.

But hey, speaking of D&D, when we first shared this image around the Mutants campfire, we were trying to identify the suspiciously LP-shaped item in the extreme bottom right of the photo. It was a long search. I had this weird feeling it was a group of musicians and I wondered what kind of jazz fusion group the nerdy beardos on the back cover of that thing could be. Lo and fucking behold, Kelly’s unwavering commitment to pop culture detective work ended with him discovering it’s the 1987 Dragonlance Legends art calendar, which not only helped us date this photo but put a real spring in my old-school 1980s AD&D nerd step. Much props, Kelly. While I wasn’t into vigilantes or the Bones Brigade, any kid with a Dragonlance calendar earns much 1987-Mike respect. We should roll up some 1st edition Krynn player characters sometime!

ROBERTS: I was just getting out of D&D at this point, Mike. But the year before, on the 8th grade “outdoor ed” camping trip, we were all playing the first Dragonlance modules, and I had read and loved the first set of Dragonlance novels. As far as comics, The Uncanny X-Men and The Amazing Spider-Man were my favorite titles at the time, although nothing here would lead you to that conclusion. I did sacrifice a comic to put the brilliant fight sequence from Uncanny X-Men #173 on my wall. Those Punisher posters—penciled by the great Mike Zeck and airbrushed by Phil Zimelman—were released on the heels of the first limited series, which did extremely well and launched the first ongoing series.

You can see The Damned’s Phantasmagoria cassette on my bed. I can’t make out any of the others, but I was very much a post-punk kind of guy (still am). How did I reconcile all of this at the time? Skateboarding, The Damned and The Cure (the goths at school were not my biggest fans), comic books, a baseball boy lamp, vigilantes and the Vietnam War? Also, what’s in that filing cabinet? How did I sleep here?

And Richard, no one uses “hoo boy” over here any more. You’ll get beat up for that.

MCKENNA: You beat me to it with the filing cabinet. Was that just standard issue American youth furnishing? Bed, bedside table, filing cabinet? I mean, I don’t doubt you had important files to put in there—and judging from the state of your room, I’m guessing files on the people you were planning to make pay for the imagined wrongs they’d done to you. But still, right next to the bed? Yep, files and a fixation with vengeful Vietnam vets—definitely in no way worrying. Also, very sub-optimal speaker positioning.

Perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but despite the fact that you could probably have found variations of everything in this picture in kids’ bedrooms in the UK, there’s a kind of cultural brashness and confidence about it that I’m not sure you could have gotten away with over our way. I don’t know how “Kool Kelly’s Place” in foot-high letters played to eventual visitors to your bedroom, but unless you were absolutely faultlessly cool, I feel like something similar would have been a social death warrant in Britain. Thatcher’s manifesting or liberating—depending on your reading of it—the individualism the country had been repressing since WWII was still in relatively early days, and acting cocky or showing off—i.e. just being mildly confident—was still a bit of a taboo gauntlet to run. This particular bedroom wall in the same period in the UK would have been a bit like daubing “Witchcraft done here” on the door of your condo in 1690s Salem. How did it play with people when they first walked in and saw you vaunting your alleged coolness like it was a Nasdaq ticker display?

Oh, and I’m still completely in the dark as to what a “baseball lamp” is, because nothing in this picture looks like a baseball.

GRASSO: As I may have mentioned in past Mutants outings, I was a pretty spoiled only child of the ’80s. To put it bluntly, I had a lot of stuff. That stuff definitely skewed towards the nerdier books-and-toys-and-things side of the ledger—I didn’t really get into sports posters or equipment or anything—but I do recall my tiny bedroom being packed full of crap. Just so Kelly’s not too alone in being embarrassed, my own bedroom had a very prominent space given over on the inside of my door to the (form) letter I received from Carl Sagan’s Planetary Society and the glossy Voyager photo of Saturn’s rings I received from same—just like the kids in that Brooklyn classroom in Episode 7 of Cosmos! As I’ve mentioned here before, my childhood idols were definitely less Mack Bolan and Frank Miller and more sensitive types like Jim Henson and Sagan.

I really dig that beige-ass push-button phone extension, Kelly. It got me thinking of when I had various electronic appliances of my own in my bedroom. I probably got my own TV in around 1985. One of the first things I remember staying up to watch was the BBC Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series on PBS. Before that, we did have a little household communal 12-inch-or-so portable black and white(!!!) TV that we moved around the house for various purposes. For someone who was arguably raised by the television, having my own cable hookup in my bedroom meant spending even less time with my folks in the living room. I think I got my own phone a couple of years later; there wouldn’t be much call for it before then, but when I got it, I used the hell out of it. I got my own stereo right around ’88, most likely, when I moved into the larger space in the basement where the IBM-compatible PC lived.

By the time I was Kool Kelly’s age in the early ’90s, my growing love of alternative rock was starting to take over my walls, along with my rapidly exploding CD collection. (As I said in Mutant Chat, Kelly, I love the Vans shoebox marked “TAPES”; this rang so true to me.) And while I never had a steel filing cabinet (which, honestly, I probably would’ve loved) I definitely had a desk to stow all my juvenilia—my stories, drawings, maps, and other scribblings. Was my room as messy as Kool Kelly’s Place? I’d like to say no, but I’m pretty sure it at least occasionally was. I’m still envying the waterbed in 2024, to be honest.

But we did live amidst great abundance, didn’t we, Kelly? As Richard points out, the same “grab all you can” strivingly materialistic impulses that were sinking into the British psyche were going truly overboard in the U.S., and kids were, as we’ve noted elsewhere, an important consumer demographic to be marketed to. From every age, the commercials bombarded us with commodities to fetishize and status symbols we needed to keep up with the classmates. Playing with Transformers or G.I. Joes with the kids in the neighborhood around 1985 was a truly fraught exercise in class envy and false consciousness. Did they have Omega Supreme or the U.S.S. Flagg? I ended up thinking a lot about whether my grade school “friends” were hanging out with me for me… or for my toys. Whether it’s something as “cool” as a computer or something as inexplicable as an inflatable Shamu (heh, sorry Kelly), our “stuff” defined us socially in a way that sometimes gave short shrift to ourselves. Pretty good training for adulthood in materialistic America now that I think about it.

ROBERTS: Yeah, you really got to the heart of it, Mike. At no other time were kids courted on such a massive scale, and never was there so much stuff to have and hold—or covet, as was often the case. It was a culture entirely to itself, entirely for kids (adults had no interest in reading our books, watching our movies, etc., and it was fucking great), and if your family didn’t have the money for these things, there was a social cost. And yeah, we did make friends with the kid down the street to get to his ColecoVision and Kenner’s AT-AT. He was a dick and held it over us, so I don’t hate myself too much. By this time I was making my own money—the real American way, under the table!—although I may still have been getting an “allowance” (if you know, you know). I was not saving a damn penny, that’s for sure.

I was pretty embarrassed by “Kool Kelly’s Place” at this point, Richard, and I was trying to cover it up with paper, graffiti, whatever. It was “kool” when I was 10—not so much when I was 15. But what a gift to get when you’re 10! My dad loved building stuff, fixing stuff, and painting projects; in the condo we lived in before this, he painted some ‘70s supergraphics all the way up the stairwell walls. I wish I had a picture of that.

A few notes: the file cabinet was a cast-off from one of my parent’s offices and used primarily as a perch for my record player; I really have no idea what I kept inside of it. The baseball boy lamp (not a “weird pickled thing,” Richard!) was probably from the ‘50s—my grandmother ran her own antique shop in Texas and sent us various vintage knick-knacks. Shamu was a show at SeaWorld featuring several performing orcas—I vaguely remember a trip to the San Diego Wild Animal Park around this time, and we must have gone to nearby SeaWorld as well. No idea how I ended up with a pool float (we did not have a pool).

MCKENNA: After looking at it for the hundredth time, I think the thing that stands out to me in this photo as being decisively American—apart from that fucking ridiculous horizontal wardrobe of a bed—is that phone. Phones were such a use-only-when-necessary thing in the UK, at least as I remember it. Maybe it was just the milieu I inhabited, but the combination of the faintly WWII-ish “keep lines free for urgent communications” vibe, an obsession with penny-pinching, and the very public placement of the phone in what was often the draughtiest point of the house, meant that making a call was usually more of a pain in the arse than it was worth. It was less hassle just to get on my bike and go round their house. So coming from that, a phone in a kids room seems like such an insane extravagance. I mean, come on: who the fuck does a kid actually need to phone? And yet it also implies a very different reality for kids, one where they maybe have more agency? Where it’s accepted that they have their own lives and their own communications needs? I don’t know, I find the whole thing quite confusing while also being immensely jealous. And with that admission, I will bid adieu to the sleek metropolitan chic of, ahem, Kool Kelly’s Room. I can sleep easy now knowing that my dreams aren’t being spied on by some weird little baseball golem.

GRASSO: When I was 8 or 9 I had some friends over to play and one of them knocked over and broke a Snoopy lamp I’d had since I was really little. (Peanuts was another media franchise I was really into when I was younger, with all the merchandising that entailed.) Oh man, I cried and cried; I was inconsolable for ages. In retrospect, it was one of those formative lessons in loss that looms larger in retrospect than you can ever fully internalize when you’re little. The attachments children have to “stuff” can be an important part of the natural process of emotional maturity, self-actualization, and ego formation. Letting that stuff go, especially when you’re anxious and attachment-prone, can be inestimably harder.

I’ve come to believe that the process of “managed loss” accompanies us throughout our lives, and it changes as we get older. I’ve radically lost the acquisitive impulses I had when I was in my twenties: chasing the newest technology, the newest gadgets, the newest phones. Why on Earth would I need more stuff? In countless moves to new apartments and houses I’ve left behind objects that once I considered sacrosanct; and now, with the benefit of time, they don’t even tug at me anymore.

Things pass away, but memories and emotions remain. If I suddenly lost the glossy books on Galaxies and the Voyager program that my grandmother got me around that time, it wouldn’t take my memories of her away from me. Those memories, specifically around how well she knew the things I loved, that she wanted to encourage my love of learning, will always live within me. This photo, and the ambiguous feelings teenage (and middle-aged!) Kelly might have had about the Kool Place his dad built, seems to fall in that bittersweet zone of how the things we possessed and the relationships we treasure intersect in our nostalgic memories.

ROBERTS: I guess what hits me hardest about this photo is that I am middle-aged Kelly (distinctly uncool), something I would have thought impossible as a high school freshman reading comics and listening to records in this pig-sty of a room. I still don’t understand how it’s possible! My oldest kid just turned 13—two years away from where I was here. Time doesn’t fly—it gushes.

Which brings us to the phone, yes? Because the 13-year-old I just mentioned and her 10-year-old sister really, really want one, but not in the way I wanted one. Not even close. When I was a teenager, it was important so that you could (a) figure out where you were going to meet up with your friends, and (b) talk to girls/boys without your parents listening. Phones now are your Identity Discs, and so many of the things represented in this photo are now mediated by the phone, or they’ve been replaced entirely by the screen. There’s good and there’s bad, I guess. As we said above, we grew up in a time of too much physical stuff, but we’re no less materialistic now. We just buy apps and streaming services and devices instead of books and records and video tapes.

Anyway, it’s not the things I’m interested in; it’s what’s inside of them: stories, music, illustration, film, games. You know—art. And I’m still obsessed with the same kinds of pop culture I was obsessed with when I was 15. Just take a look around the site. It’s all here. This is our room.

Ain’t No Golden Age: On the Banality of Nostalgia Memes

Features / November 27, 2024

In my mind and in my carWe can’t rewind we’ve gone too farPictures came and broke your heartPut the blame on VCR

—The Buggles, “Video Killed the Radio Star”

ROBERTS: I saw this on Facebook the other day and had to call an emergency round robin. I don’t know the original image source but I’ve seen it on several clickbait nostalgia pages at this point. The amount of “sad but true” comments is staggering, made more perplexing by the fact that most of these comments are from people who claim to have lived through the ’60s and ’70s. The image is important because it captures something desperately tragic about where we’re at and how we see ourselves. It is, quite simply, Big Brother level propaganda. This version of 1974 never existed (we’ll get to 2024 later). Nothing about it is right. Where are the cigarettes and ashtrays? Where are the beer bottles? Why is everyone bronze-white? Where are the tablecloths (is this 1974 or 1874?)? Why the fuck is that giant window there? Is that a chess board on the table? The answer is so ironic that I can hardly stand it: the cartoon was generated by AI, which is the product of the (alleged by the second panel) grim and joyless and mercenary technological age that the cartoon attempts to condemn.

GRASSO: Yeah, we can very safely put aside all the aesthetic elements of this atrocity that are attributable to the fact that it’s AI: the color grading, the inimitable and easily discernible Escherian uncanniness to all the visual elements, the kitsch factor, the utter lifelessness of the art itself. That’s all baked into the material reality of AI art. We’re dealing with a nostalgia meme made for Facebook here, for Christ’s sake—of course it’s going to bore a hole of distilled banality into the viewer’s skull. But still: someone, some actual human somewhere had to feed this thing a prompt. Some part of it came from an actual human mind. And what that mind wanted to convey with this thing is “wasn’t it better when social spaces were truly social and we weren’t all sitting around on our phones, isolated from each other?”

Leaving aside another grand irony—the fact that this meme ended up finding fertile ideological purchase on the internet, on those very same phones—there is a certain libidinal thrill in all these generational memes, whether visual or textual: a violent, agitated staking of psychological territory, projected in a threatened, growling voice onto the younger generations on the internet, a statement of misplaced solidarity and pride: “REMEMBER WHEN WE DRANK FROM THE GARDEN HOSE, GENERATION X? REMEMBER HOW WE USED TO SPEAK TO EACH OTHER AND LAUGH IN PUBS? NOT LIKE THESE MILLENNIALS AND ZOOMERS, ALWAYS ON THEIR PHONES.” The implied distance between the “good old days” and today is shrunk down to the most elemental of caveman emotional urgings: “then happy, now sad; we from then, we better than you.”

The vibe here is almost poignantly desperate in a way, giving the impression that the older generation is almost glad things are this bad in 2024, because it allows them to stand in smug superiority against those “young people always on their phones.” When the past is a frozen tableau, painted by AI, nothing can harm it anymore or expose the truth about those 1974 pubs and bars: they weren’t all limned in golden sunlight, full of happy people singing and chatting. In fact, they were often grotty, violent, and full of alcoholics just as hypnotized by their beers as the millennials and Zoomers are by their phones in the 2024 image.

MCKENNA: At a guess, this is from my side of the pond, because us Brits—or more specifically us simple English folk—just love this kind of shit. And if that is the case, a few of the incongruities do kind of make sense. Even the absence of any ethnic minorities can probably be explained by a combination of extra-urban demographics, varying cultural attitudes to boozing, a general diffidence towards outsiders, as well as pretty widespread bigotry. To be honest, in the late eighties the majority of pubs outside metropolitan Bohemian zones weren’t all that welcoming even to your average random straight white male, so anyone not belonging to that group would have been forgiven for thinking twice before popping in for a disgusting pint of Skol or Harp ten years earlier. As would anyone who spoke with an Irish accent, given that the Provisional IRA had begun carrying out attacks in mainland Britain the year before—1974 was in fact the year the Birmingham Pub Bombings happened—so suspicion of strangers was through the roof. The whole year in the UK was pretty fucking horrible, to be honest. Bagpuss debuting on TV was about the only good thing that happened.

But though pubs like this do—or did—sort of exist, the vibe feels more like a wish-fulfilment melding of the atmosphere of some twatty village pub in the Cotswolds, where the farmhands still live in some Wicker Man-esque idyll of rural submission to the local landlord, with that of a working men’s club, places which I remember as having a much more balanced mix of the sexes and a very different and more cheerful mood. To give you an idea, the only picture I have of my dad drinking a pint (of shit lager, natch), he was in a working men’s club: the man won’t set foot in a pub. And as Mike says, pubs could be hostile places, full of aggro alkies looking to start on anyone who looked a bit odd.

Anyway, the main things missing are the dense cloud of acrid smoke and the bitter cold, which is my abiding memory of the few times I entered a pub before I was ten, and the frequent air of lurking threat from some pissed-up yobbo, which is my abiding memory of pubs in the ’80s and ’90s. Oh, and the stench, which is admittedly hard to render in pixels. Most pubs got fitted carpets at some point post-WWII, and most pubs never changed them, so years of absorbing revolting yeast-heavy spilled beer—and probably a surprising amount of urine—meant that the places often fucking reeked. A friend and bandmate very kindly got us some occasional work cleaning the pub his stepdad ran in a small provincial town on our dinner breaks from school, and the reek of sour beer in the place was fucking nuclear. I actually preferred cleaning the toilets, because at least the urinal cakes drowned out the various other stenches. And this was not a smelly pub, it was a well-looked-after one! So yes, this is a combination of good-old-days nonsense with the kind of idyllic, cozy vision of pub life CAMRA (Campaign for Real Ale) was aggressively pushing in opposition to the increasingly corporate mindset governing what had visibly become an industry.

ROBERTS: The question of where it comes from is an interesting one. Many of these nostalgia sites are run out of Europe (several from the Netherlands), but they generally target American clicks. The pint glasses would explain the absence of bottles if these weirdly Stepfordian people were in Britain, but look at the “band,” at least two of them clutching instruments that don’t exist in the real world! And look at all the gleaming wood, and the curtains! Add a couple of cowboy hats and we might be in the small-town world of Little House on the Prairie, which was itself a nostalgic idealization of American frontier life in the late 19th century. It was a hugely successful TV show that premiered in—you guessed it—1974, a little over a month after Nixon resigned. The year also saw mile-long gas lines, stagflation, smog sieges, kidnappings, hijackings, and parents were still smoking cigarettes in cars with the windows rolled up. For a lot of Americans, 1974 was less like a country band jamboree and more like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Listen, I do lament the fact that so many people, including me, are buried in their phones for too much of their lives. We don’t, as societies, talk as much as we used to. We don’t have the physical spaces that we used to have that gave us common ground and a shared reality that actually resembled reality. But the most Orwellian thing about 2024 is not people looking at iPhones, it’s Trump, whose slogan is the fuel behind this poisonous meme.

GRASSO: A few weeks ago comedian Conner O’Malley and a cohort of fellow millennial comedians put out an hour-long film called Rap World. Set in January 2009, right before the Obama inauguration, and shot on period-appropriate equipment, it tells the story of a single night in the lives of a bunch of aimless young people in the Pennsylvania exurbs recording an “intelligent” rap album. Much of the commentary on this very funny film came in the form of younger millennials and Zoomers enviously noticing how much “simpler” and less distracting life was, or at least seemed in… 2009! Cell Phones existed, but most of them didn’t give us full access to the internet; there was more of an overarching monoculture, more opportunity and desire to be social in real space. Think about how many of the most beloved nostalgia pieces of the past half-century—American Graffiti, Dazed and Confused, hell, even the music video for the Beastie Boys’ “Hey Ladies”!—mine the cultural and social touchstones of only a decade or so in the past! Juxtaposed with this Boomer/Gen X AI atrocity… Well, I guess what I’m getting at is that every generation can fall into their own traps of thinking things were cooler and better and easier, that they just missed out on the Best Era Ever. One can always locate a perfect moment in the past, even as that distance between idealized history and harsh present shrinks more and more as technology peddles nostalgia to keep us from asking the very pertinent question, “What is to be done?”

Obviously we’ve talked a lot about nostalgia at We Are the Mutants over the years. One could even argue it’s all we’ve talked about in one way or another. I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about nostalgia myself recently; nostalgia and Trumpism, nostalgia and political reaction, nostalgia and dissatisfaction with the world we’ve handed down to ourselves (because ultimately, we’re all responsible for the atomized world we’ve inherited). If things were so much better “back then,” why do we collectively find it so hard to make a world we do want to see and live in now? We have a blueprint, after all, thanks to this idiotic AI image and countless thousands of others just like it. What elements of our present world are so irrevocable and irreversible that we can’t just pick ourselves up, put our phones away, and go to a pub and hang out with our friends? What, substantively and specifically, are the obstacles to a better, more meaningful life with richer, more fulfilling social experiences? If we were to start asking deeper, more specific questions like these, answers might emerge that some people—the ones who profit most from our current system—might not like us to have awareness of: economic and employment precarity, a deliberate closing down of public third spaces, sky-high rent that prevents working- and middle-class people from opening their own third spaces, less free time because of the demands of a 24/7 workplace, and the lack of energy that comes along with it that discourages us from planning and attending social events. One can blame technology, “phones,” for all of this, but that’s only identifying the symptom of the underlying disease. That disease is within us all and it’s called capitalism, kids. Sorry to be the kind of strident communist bore you’d probably slowly disengage from down t’pub.

MCKENNA: Of the three of us, I’m probably the one least irked by nostalgia. Partly because of a desire, however clumsy, to maintain a link with your past and your past emotions in a world where commerce demands that things change constantly seems pretty natural. And partly because—perhaps too forgivingly—I tend to see nostalgia more like a repressed acknowledgement of how terrifying the passage of time is than something more worrying. Seeing the past reminds us of the diminishing amount of future we have left, and that’s distressing, so instinctively we cling onto it. So there’s a part of me—namely most of me—that does empathize with the nostalgic. But then there are these scumbags eager to channel that distress into the hideous pipelines they’ve constructed with the goal of getting attention, or clout, or power, or just riling people up or whatever. People like the dickheads who made this picture.

That said, go into any pub, at least in the UK, and I am fairly certain you won’t see anything like the bottom scene. I mean, you’ll 100% see horrible, soulless structures all painted grey or whatever modish color scheme is currently in vogue—it’s got that right. And you’ll see a few people on their phones, ignoring everyone else. But you don’t need a phone to ignore everyone else—the world’s full of people who are quite capable of ignoring you even while they sit across from you and pretend to have a conversation with you. If you go into a pub, though, I’d say most of the people will be engaged, be it with each other or with getting absolutely rat-arsed on revoltingly overpriced IPAs. They’ll be talking shit, much of which will be stupid and possibly offensive, but they’ll be talking. So, while I agree that phones are unhealthy and we spend way too much time on them, I’m unwilling to subscribe to the phonophobia the pic wants to elicit. Without phones I’d be far, far less in touch with friends and family. I’d never have met you two. Wouldn’t have done the website. And the implicit presumption that people doing something on their phones is supposedly less—productive? Worthy?—than them just staring into space, or reading some shit book, also seems a bit optimistic, as if reading is axiomatically valuable even if what you’re reading is absolute dog turds, while whatever appears on a phone screen is automatically drivel.

Basically, I’d be lying if I said that the top pic, despite everything fake and stupid about it, didn’t pluck faintly at my heartstrings—because I’m exactly the kind of idiot this shit is designed to hook. At the same time, the comparison with the bottom pic is exactly the kind of fraudulent bollocks this stupid meme wants you to believe it’s railing against.

ROBERTS: I’ll tell you why this image made me so angry. Because at first glance, I bought it. I thought to myself: “Jesus, life was so much better in ‘74.” And then I saw the “singer” with the microphone stand jutting out of his wrist, and the zombified faces of the old men in the band, and the distorted dart board, and the non-existent musical instruments, and so on. We’re all susceptible, especially those of us born before the internet took hold. I’ve said before that nostalgia is a fantasy, and I enjoy it as such. But unchecked, it becomes something much worse: delusional Golden Ageism that’s often empowered by contempt for people who are different than you.

I don’t know what’s to be done. I think we have to start by being honest with ourselves about a lot of different things. I think we are always going to look back and yearn for the glory days—it’s part of getting older and being human, and every generation does it. But we have to recognize that this idea of looking backwards for a way forward has become a pernicious social and political obsession. I can’t say I’m a communist, Mike—I know you’ll forgive me. I’m a boring old RFK (the good one, not the shitty one) Democrat. I do believe that when money controls the tools that can make life better for everyone, it’s a good bet that life will only get better for those with money. And when the combined technology of AI and smartphones and social media is leveraged to venerate a time before the technology of AI and smartphones and social media, you can be sure that making life better for everyone is an idea whose time has come.

“An Important Place in Their Lives”: Musicland Sales Brochure, 1978

Recollections / November 12, 2024

ROBERTS: I don’t know if I told you guys this, but I worked at Musicland/Sam Goody for a couple of years in the early ‘90s, a pretty good time for popular music. I was actually a store manager for a few months—yes, Richard, it’s true—before my location closed down (there was another Musicland down the street in the mall). That’s what you did back then—you worked in stores that sold the stuff you liked so you could buy more of the stuff you liked. This brochure is before my time, and that’s probably why I find it so fascinating. The ‘70s aesthetic is in full effect, and I forgot just how much merch you could get at “the record store”: stereo systems, speakers, transistor radios, tape recorders, sheet music—even guitars! But it’s the intimacy and immediacy of this environment that gets me. How do you describe to someone who hasn’t experienced it before exactly how it felt to walk into the record store before the internet? When music was your life.

GRASSO: I first took a trip to the record store in what would have been late 1982 or early 1983: it was the Medford, Massachusetts location of the Northeastern US chain Strawberries and I came in search of 45s of two songs that had been in heavy rotation on our newly-acquired cable box’s channel 25, MTV: Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me With Science” and Toto’s “Africa.” I found a lot more there, though, thanks to the giant sales catalog, bigger than a city Yellow Pages, full of import and (presumably) out-of-print vinyl. I was only seven years old, so I was a little overwhelmed by it all, but thanks to that Big Book and the help of my dad and the clerk I was able to grab a copy of Dolby’s The Golden Age of Wireless, which I seem to remember being in short supply in the record racks.

It’s kind of amazing that I’m able to access those memories 40-plus years later—but that’s the impact that very first trip to the record store had on me. I’d drift away from music after my initial early-’80s spate of 45-purchasing (Tracey Ullman’s “They Don’t Know,” Yes’s “Leave It,” and the Kinks’ “Come Dancing” were some of my other early-MTV-inspired singles purchases); it wouldn’t be until junior high in 1987 that I’d start going to the mall on my own to buy cassettes and eventually CDs. Our record chains in Boston—Strawberries, Newbury Comics, and the big HMV and Tower Records outlets in Harvard Square—were great for finding import CD singles and discovering new local favorites, but I also treasured a little hole-in-the-wall used record store on Route 1 in Saugus, whose name very sadly escapes me at this time.

These stores all had knowledgeable clerks who, if you were able to demonstrate your cred by asking for the “right” album, would put a young, uncertain music fan on the path to finding new artists who’d join your personal pantheon of favorites. Posters, music periodicals, merch of all kinds, ways of proving your fandom: the local record store was a place to equip yourself for doing battle in the trenches of junior high and high school music-cred combat.

MCKENNA: Hmm, what a peculiar coincidence: you were a store manager, Kelly—and then the store closed down, you say? Yep, that definitely sounds like the fault of the other Musicland in the mall, not of the vision-impaired management style that almost deprived the world of the best Phil Collins article that has ever been written. Anyway, you two city slickers seem to be forgetting something: like John Denver, I’m a country boy, and in the provinces of Airstrip One, record shop history follows a slightly different timeline. The chains like Our Price, HMV, and Virgin Megastores didn’t arrive anywhere outside of London until way later than in the States, and when they eventually did, the light-years-out-of-my-league goth girl I fancied from school started working in the only one I could get to, which did not exactly incentivize me to spend my supermarket trolley-boy and lettuce picking money there.

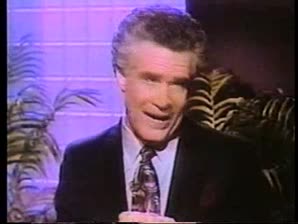

In any case, at least as I remember it, record buying in Northern England at the time was more likely to be in independent shops like Jumbo in Leeds or Red Rhino in York, or in the more institutional environs of a Sydney Scarborough or a Bradleys. If you were seeking the full beige rainbow of corporate experience, the music departments of the W.H. Smiths shops dotted around the country were for a long time perhaps the nearest thing a lot of us outside London had to something like Musicland. The people running the Smiths’ music departments often seemed to have a weirdly free hand about what they could have in stock (which could be good, or could mean the LP section suffocating under the weight of the thirty least-appetizing Zappa LPs). Was that similar to what went on at Musiclands, or was the choice of stuff more corporate generic? Also, where can I get a copy of that killer Moody Blues poster? And Kelly: which of the Musicland management styles modeled in the brochure photo top left were you channeling? Stranger Danger, Cromwell henchman, Lawyer who thinks he’s outsmarted Columbo, Italo-American SFX tech at the Academy Awards, John Boy Walton, or that slick MF on the right?

ROBERTS: I’m not sure I had a style other than “you watch the store while I smoke and I’ll watch the store while you smoke,” because we were all pounding Marlboro Reds in the back room whenever we could. I remember pulling all-nighters at various stores to put all the cassettes and CDs into the new security trays (“shrinkage” was every retail operation’s worst nightmare). The manager would order pizza and during “lunch” we would wander around the dark, empty mall and the corridors behind the stores. To answer your question, Richard, we did not really have a free hand in what we stocked—it was a pretty corporate environment—but we did get to open and play “store copies” of new music, and we could special order the obscure stuff we wanted to hear. I remember playing the first Weezer and Sunny Day Real Estate LPs, Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, Nirvana’s In Utero, Cypress Hill’s Black Sunday, PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me. As long as the district manager was not around or rumored to be around, we were good.

Record stores were where we bought our concert tickets too, although we didn’t do that at Musicland. There was another store called Music Plus (we had a lot of chains in SoCal) that was the go-to for tickets. One of the employees would bring out a binder, show you a layout of the venue, and tell you how much the tickets were for each section. But nothing beat Tower Records—I still have dreams about sifting through the import section, discovering lost albums from my favorite bands. As we’ve talked about time and again (ad nauseam to some, I’m sure), these physical spaces were designed to take your money, but they were also where we discovered art and, yeah, meaning. Remember that line from Dawn of the Dead? Francine asks Stephen why all the zombies are trying to get into the mall and he says: “Some kind of instinct… Memory of what they used to do. This was an important place in their lives.” That’s me. I’m one of the undead now.

GRASSO: Probably as good a time as any for me to get (historical) materialist about the mall record store from the consumer side, seeing as how I have no behind-the-scenes memories of working at one (my college job was at a video rental joint, which had its own set of amazing fringe benefits, not the least of which was free unlimited borrowing privileges).

After my MTV-inspired single-purchasing in 1983, my music-collecting years with my own hard-earned money kicked off in earnest in the late 1980s, and thus I was fortunate enough to get in on buying compact discs on the ground floor. My friends who were just a few years older than me had massive cassette collections they’d assembled throughout the ’80s; honestly, I don’t remember many of them owning much vinyl at all. And dollars to donuts, I bet the seedling of most of those tape collections were courtesy the Columbia House Record Club, the infamous direct-mail outfit that would send you “8 tapes for a penny” and then shackle you to an onerous “negative option billing” obligation that could be very difficult to weasel out of. Score one more for the friendly local record store.

So yes, from the very beginning of my time as a music consumer—around 1987, 1988—CDs were my format of choice. Remember longboxes? Those massive, wasteful cardboard sleeves were developed for the CD specifically because physical record stores didn’t want to refit their LP-sized storage racks (and because, like tapes, CDs shorn of these boxes were easy to nick before the rise of anti-theft RFID tags). Sort of laughable to think about these half-empty cardboard sleeves cluttering up shelf space and landfills just so the record stores would promote this new format, but the music industry has always tried to get consumers to (re-)buy their favorite music on an “exciting” new format, going all the way back to Thomas Edison.

The CD also outpaced the LP and cassette on price during this era: I cringe to think of blowing my meager early-’90s wages on a few $14.99 CDs a week while vinyl and tapes were still going for, like, $7.99 or so. (Let’s see, a $15 compact disc in 1990 would be the equivalent of dropping nearly thirty-seven 2024 dollars on a new album, according to the always-shocking Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index calculator.) Sure, the artists didn’t get a huge cut of my afterschool job money (RIP Steve Albini, who nailed the state of the record industry and its exploitative garbage at this very moment in history pretty much perfectly), but at the end of the day the artists got some of it, and I had a physical emblem, a totem, a real piece of art—yes, even in CD jewelboxes!—that served as a testament to my love for a band.

Think about all the jobs that existed in this very conspicuously late-20th century supply chain: the execs, the artists and repertoire scouts, the producers, technicians and engineers, the bands and their entourages, the label designers, comms personnel, promoters, the radio DJs playing the records, the manufacturing plants, the intermediaries bringing the CDs, posters, buttons, and merch to the record stores, and all those Marlboro-smoking clerks like Kelly in malls across the country. A good chunk of these jobs just don’t exist anymore. Seems pretty obvious which end of the labor pyramid got screwed over the past 30 years—and it wasn’t the execs.

Of course, when the 20th century ended and the nascent Internet enabled file sharing to take off, the industry bigwigs definitely panicked about the future of music. But in the end it wasn’t the suits who lost their livelihoods—it was the artists. And for the past quarter-century, pop musicians have been bifurcated into a two-class system: giga-stars whose (over)exposure ensures they never have to worry about a paycheck again, and touring musicians forced to sell merch like carnival barkers just to make a (barely) living wage. Like everything else under late capitalism, the music industry has materially consolidated, diluted its product’s quality and diversity, and turned a thriving, living underground into a manicured garden where spontaneity and apprenticeship have largely vanished as concepts. As Kelly says, the locus at the base of that massive commercial pyramid was the local record store, where taste was made, music was shared, and fans’ connections with the band were consolidated.

MCKENNA: One thing that saves me from feeling like some deranged, backwards-looking nostalgist troglodyte, constantly harping on about how things used to be better back in the Mesozoic, is that one of my day jobs involves teaching Zoomers. Their fascination with the random, uncurated physical realities that used to be part and parcel of engaging with music, art, people, and the world in general—before business got so good at interring you inside your interests—reinforces my feeling that having stuff like Musicland around actually was just objectively healthier. Yes, it was an anodyne corporate product of aggressive capitalism, and yes, more egalitarian situations that foster a wholesome tactile involvement in the world are definitely imaginable, but as shitty as it might have been, it was at least real, ergo better.

This is something that I think gets lost in the—sorry for using the horror word—discourse around these things: there’s this implicit idea that as a society we just naturally evolve past certain realities, and that to think of them fondly, or even—god help us—think they might have been better is somehow axiomatically regressive. I think that’s bullshit for several reasons, but mainly because we didn’t evolve past them at all: they were removed in service of someone else evolving themselves more money. Like I say, you can argue that they were in any case the products of unfair wealth and extrusions of capitalism into our imaginations, and you’d be right, but isn’t the way things are today an even more brutal product of those forces?

When I reminisce with people my age about the immersion in physical reality that was necessary to buy, say, the 12” of Genesis’s Mama, their perspective is often purely one of convenience, but if I talk about it with a 16-year-old, their reaction is often ecstatic shock, because they sense the increased possibilities that the less curated experiences inherent in the kinds of spaces you two are talking about offered. Even when they were the kind of shitty corporate boxes that would employ someone as musically illiterate as Kelly.

ROBERTS: Look, we’ve all discovered quite a bit of great music cruising around the internet, and we’ve written about a ton of it, from library music and ambient to ‘80s pop and sci-fi synthesizer epics. Sometimes, the algorithm works (God bless Sounds of the Dawn, for instance). Was the record store better? I don’t fucking know. We’d have to ask more of Richard’s students. What I know is this: if I ask Pandora or Spotify to make me a playlist based on, say, This Mortal Coil’s cover of “Song to the Siren,” I’m going to hear a lot of good stuff. If I ask you guys to make me a playlist (or, better, a mixtape) based on that same song, I’m going to hear a lot more good stuff—as long as you don’t fuck around and throw Phil Collins into the mix. The difference is that you know me, and the algorithm doesn’t, and it never will.

Also, the process of discovering music was fundamentally different when we were young. One of my favorite albums is The Chameleons’ Strange Times (1986). I heard the first American single, “Swamp Thing,” on KROQ’s Rodney on the ROQ, a late night LA radio show that played underground/alternative music. I had never heard anything like it—I was obsessed. Every night (for days? A week? Two weeks?) I waited for Rodney to play it again, a blank tape ready in my boombox, my fingers ready on the orange-red record button. He finally did, and I taped it (the songs weren’t always introduced before they were played, so you had to be quick), and I listened to it over and over again. Bought the LP when it came out in the States. How did I know when the album came out? I kept asking the clerks in the record store. I still remember pulling the record out of the bin at Tower, marveling at the cover, taking it home, putting it on my record player. Would the whole thing be as good as the single? (Yes!) I still smell the cardboard and the plastic sleeves that protected the vinyl. I still see the labels on the middle of the LPs (Strange Times is a double album). It was a physical experience—call it crass and materialistic—and a spiritual experience all at once: from the radio to the record store to the home record player. Every time I hear the album, all of the emotions inherent in that process of discovery are embedded in the experience of the music itself.

There. I have tried my best to describe to someone who hasn’t experienced it before exactly how it felt to discover music before the internet.

Tubular Terrors: ‘The Possessed’

Reviews / October 25, 2024

The Possessed

The PossessedDirected by Jerry Thorpe

NBC (1977)

The ladies, eh? Can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em and all the perfectionism, repressed frustrations, sexual/sibling rivalries, and fear of aging that make them the perfect conduits for Evil to manifest itself.

Before I’m rent limb from limb by justly enraged women, let me explain that those are not my sentiments: they’re the thesis that, at least superficially, seems to underpin 1977 TV Exorcist knock-off The Possessed. Because women—sorry, I mean Evil—is up to its old tricks as the academic year comes to an end in the Helen Page School for Girls in, natch, Salem. Not that Salem, though—Salem in Oregon, though the school is actually snooty Reed College in Portland, going incognito here because, despite annual tuition fees today of around $70,000, you presumably can never have enough cash to guarantee the kids of the elite the basic amenities they require.

Never fear, though: sullen ex-priest Kevin Leahy (James Farentino, who I will refer to mononymously as just “Farentino” not out of any desire to sound like a proper writer but rather because, like Sembello, when you’ve got a surname that punchy, the Christian name feels like it’s just dangling there to no real purpose) is here to pace gloomily and seemingly randomly around the corridors of the school until Evil is kicked the fuck back to hell. We first meet him still frocked but with his faith in tatters, sucking on a bottle of Jack Daniels in the sacristy and morosely pronouncing mass in a doomed-pilot-episode-esque flashback prologue. Driving home from the day job that evening, he drunkenly totals his car against a utility pole and finds himself facing the final judgement. He’s fallen from God’s grace, he’s informed, and his only hope for redemption is to “seek out evil and fight that evil by whatever means… possible.” Next thing you know, he’s been Lazarused back to life with a powerful “in this week’s episode” vibe.

Cut to the Helen Page School, where graduation is coming up. Our introduction to the place is an incongruous and oddly unnerving scene of screaming girls riding bikes along the school’s corridors, which is a nice way of evoking the charged atmosphere: the girls are restless to get the hell out of there, and the following year the school’s going co-ed, so everyone’s a little itchy, especially brittle and unhappy-seeming headmistress Louise Gelson (Joan Hackett), whose widower sister Ellen Sumner (Claudette Nevins) is a teacher at the school. Before long things start bursting into flames—curtains, pieces of paper, girls’ clothes. What’s the cause? Is it some kind of prank by the student body, bored teenage girls famously a nexus for mischief in the popular imagination? Is it Ellen’s daughter Weezie (Ann Dusenberry) pulling a Carrie? No—counterintuitively, it’s Han Solo.

Because the cause of the upset turns out to be hunky biology teacher Paul Winjam, played by a young Harrison Ford in what looks like his last role before Star Wars. After breaking off his secret fling with headmistress Louise, Paul’s now taken to fooling around with her niece Weezie. Plus, he’s also kind of a dick in other ways, as evidenced by his edgelord biology lessons where he gets his yuks by putting the girls on the spot to nominally teach them important lessons about fear. Before long, though, Winjam gets his comeuppance in a scene that feels weirdly and cathartically like the Indiana Jones franchise terminating itself with purifying flame. The film culminates in a poolside battle between good and evil that’s resolved by Farentino meting out a couple of hysteria-resolving, patriarchy-affirming slaps before nonsensically jumping into the water and disappearing into the limbo where un-picked-up pilots go to be judged.

Blatantly trying to ride the audience numbers of 1973’s The Exorcist, the same year’s Satan’s School for Girls, and 1976’s The Omen and Carrie, The Possessed is, predictably, imbued with the whole period’s ubiquitous post-Watergate feeling of gloom and hopelessness—so grim and overheated that at times even the stolid Farentino looks afraid. It’s almost as if the real supernatural force at play is the dumb joie de vivre of the almost-Gen-X teen schoolgirls pushing against the cynicism, fatalism, and malaise of the conscientious but emotionally misshapen adults. “Is this happening because of me?” asks a tormented Weezie. No, Weezie—it’s happening because of depressed boomers.

Written by John Sacret Young, who also wrote We Are the Mutants “favorite” (trauma nexus) Testament, directed by stalwart Jerry Thorpe, and starring a cast of troopers so seasoned they would never need refrigeration, The Possessed is more a work of competence than inspiration. And yet. Despite everything daft, derivative, pedestrian, and flagrantly sexist about it, The Possessed does somehow contrive to be unsettling. Like all horror that actually horrifies, as opposed to performing the spectacle of “horror,” there’s a vague sensation that even the people making it didn’t really grasp quite what they were channeling. It’s a feeling that lurks in inoffensive yet surreal scenes like the one where a group of girls prank their roommate by covering her bed with a disgusting pile of gunk, or that strange introductory image of the girls riding bikes through the corridors. I’ll be honest, I went into this review half-hoping to write a smug guffawing takedown, but the unhealthy miasma of repressed and unacknowledged emotion that fills the school and the film—and maybe Hollywood itself?— wrongfooted me completely.

As is often the case, the dreariness of the plot and the film’s visuals—which presage 1980’s The Changeling—actually contribute to its oppressive mood, and the cast all put in far more effort than a cheapo TV knock-off like this probably deserves. The poolside denouement is both oddly underwhelming and deeply strange—who the fuck ever got machine-gunned with the Nails of Christ?—and the possession make-up weirdly effective, however low-rent. And I can’t think of many other films where the sensations of being physically hot or cold seem quite so tangible.

In conclusion, The Possessed is gloomy fun, and it’s a shame it didn’t end up getting commissioned as a series. Who in their right mind wouldn’t have wanted to watch an episode of this shit every week to wash the foul taste of Highway to Heaven out of their mouth?

Alien Renaissance: An Interview with Illustrator Bob Fowke

By Richard McKenna / May 6, 2024

Of all the visionary artists to emerge from the illustration boom of the ’60s and ’70s, Bob Fowke must be one of the most unfairly neglected.

I first became aware of his idiosyncratic visions through his covers for Sci-Fi 1, 2 and 3, anthologies of specially commissioned science fiction stories for young children published by Armada books in the mid-’70s. To an extremely literal-minded (though people who knew youthful me might say simple-minded) child like myself, obsessed with very literal-minded depictions of spaceships and alien worlds, Fowke’s pictures hit me like a bucketful of acid dumped into the South Yorkshire water supply. Beguilingly tactile and alluring with their bright colors and odd forms and technologies, they were at the same time worryingly surreal, seemingly communicating things that they weren’t overtly saying.

Even among the plethora of gifted artists working in the field at the time—particularly the stable of his peers at art agency Young Artists, which included Les Edwards, John Harris, Colin Hay and Peter Elson—Fowke’s vision stood out, at once playful and disconcertingly strange. Once aware of him, I started noticing his work all over the place: on Angela Carter books, on the cover of Nicholas Fisk’s great juvenile SF gem Flamers in the library, and in 1980’s faux galactic travelogue coffee-table book Tour of the Universe.

So sincere thanks to Bob for agreeing to be interviewed, and to his wife Pinney for being the trigger for it happening. Please visit www.bobfowke.co.uk to learn more about him and see more of his work. All of the images used in this article are © Bob Fowke, with all rights reserved by Mr. Fowke.

* * *

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

FOWKE: I’ve always been interested in art—I’m hardly alone in that—but perhaps no more than in literature and some other subjects. After school, I completed a foundation art course at Eastbourne College of Art, but I was more determined to learn the craft of painting than I was ambitious to be an “artist,” whatever that meant at that time. I would have preferred an apprentice system such as artists received in the Renaissance period. With this in mind, I went to Taunton College where I was able to study the craft of illustration under John Raynes, a well-known commercial artist of the 1950s/60s. His style is completely different to mine, but his discipline and the opportunity to watch a very competent professional artist at work were invaluable.

MCKENNA: How did you first find yourself involved in book jacket illustration?

FOWKE: Given that my work is, I hope, imaginative, book jackets, which are advertisements for products of the imagination, were by their nature where I would be at home and where I could get commissions. I painted some record sleeves and adverts, but book jackets were my bread and butter.

MCKENNA: Did you have any interest in the science fiction and fantasy genres before you began working in the field?

FOWKE: Perhaps sci-fi attracts young men because it tends to privilege concepts and plot over emotion, even if the best sci-fi writers often encompass emotion as well. So, I read science fiction/fantasy as an adolescent but as part of wider reading.

MCKENNA: How did you become involved with Young Artists and what were your experiences working with them?

FOWKE: On leaving Taunton, I sent some sample paintings to Young Artists, a remarkable illustrators’ agency of that period, and they were accepted immediately; I was fortunate that there was no period when I was searching for work. The images I sent were completely off the wall but John Spencer, who started the agency, saw something in them despite them being a bit mad. It was very good luck, and very kind of him to see something in my work.

Young Artists were wonderful. We illustrators were scattered all round the country because we could work anywhere, and there was a wonderful party once a year, held in their warehouse offices in Camden town, when we all descended from our scattered studios in the provinces and elsewhere. They were a great agency to work with and, as it turns out, quite historically significant.

MCKENNA: What are your memories of working in that period? Which of the projects you worked on were most memorable and why?

FOWKE: I moved to Shrewsbury with my young family and worked hard, putting my finished artwork on “red star,” a same-day delivery service by train to London. In my case there was a sort-of tri-weekly turnover of work I should say. There were no personal computers, no fax even.

There were so many projects, I can’t say which was most memorable. Perhaps it was painting the little dinosaur cards that went in Kellogg’s cereal packets, although not for artistic reasons. The artwork was very small and I worked so many hours each day that my eyes grew weak until, by the end, it took five 100-watt bulbs directed at the artboard for me to be able to see what I was painting. The eyes recovered, fortunately.

MCKENNA: Which artists—or films, authors, musicians, etc.—have exerted the biggest influence on you over the course of your career, and are they the same ones you find compelling now?

FOWKE: My tastes are boringly similar to a lot of people’s. To name but a few: Mozart and Beethoven, Samuel Palmer, Bosch, Constable. There’s a reason why these people are so famous.

MCKENNA: At least to me, your artwork seems to inhabit a space where Renaissance and surrealist visual sensibilities bleed into one another to create something that evokes both, but which feels very much like its own thing. Am I way off the mark?

FOWKE: You’re spot on. When I started painting book jackets I was especially influenced by Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Durer and some of the Italians, as well as by Magritte and the surrealists—-but I attempted to use their visual language to create a subjective reality of my own.

MCKENNA: You did your foundation at Eastbourne School of Art. Do you think that growing up on the South Coast of England informed your art?

FOWKE: I was brought up in Brighton and attended Marlborough College, then Brighton and Hove Grammar School, as it then was. Like most artists, I’m always influenced by the landscape around me, and in those days it was the South Downs, but I doubt the influence goes beyond that.

MCKENNA: How do you typically approach the composition of a piece?

FOWKE: Pencil, paper and free-association first, then work into it.

MCKENNA: I have the impression that your work has perhaps been a bit neglected because it’s somewhat less literal in its visions than some of your contemporaries. Would you say that’s a fair judgement?

FOWKE: I think you’re right. I wanted to paint my own subjective visions and those are things that are hard to pin down—-and who’s to say if they’re always what other people want—-if they don’t fit neatly into a particular genre.

MCKENNA: When and why did you begin to move out of illustration and into publishing?

FOWKE: It’s a very solitary occupation and at a certain point I needed others around me. Then, of course, I took up writing and that’s also solitary. A fool is a fool is a fool!

MCKENNA: What are you up to nowadays? And are you still painting?

FOWKE: I live in South Shropshire and I’m still painting and writing as well as helping others publish their books through YouCaxton Publications. There’s a lot to do.

MCKENNA: Is there a project that you’d like to paint but have never yet managed to get around to?

FOWKE: Several projects.

MCKENNA: Is there one painting of yours that you think represents particularly well what you wanted to accomplish with your art?

FOWKE: If I were to select a “Desert-Island” painting, I would choose one of the three I painted in India in 1980 for Alien Landscapes. I had a lot of time for each one and the level of detail in those paintings, if I say so myself, is exceptional; you need a magnifying glass to really appreciate them. I was illustrating Brian Aldiss’s story Hothouse, which involves a tree that covers the world, and for the first painting I took a room at the Theosophical Society in Chennai, which has one of the world’s largest banyan trees in its grounds. I ended up painting a small square of ground at its feet and no tree in the painting—a long way to go for a small square of ground but such are the workings of the subconscious.

MCKENNA: And finally: if you could pick any painting by any artist to hang in your otherworldly residence, what would it be and why?

FOWKE: Right now I would go for a Fragonard, The Swing obviously, or a Boucher, or even a ceiling by Tiepolo. In fact the ceiling would be the best value because I would get more of it. I love the exuberance and optimism of the Rococo style. But I might change my mind tomorrow.

One of Bob’s more recent pieces, Why I Like Angels

![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being one day rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being one day rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Truckin’ for Souls: Explo ’72 and the Jesus Revolution

Michael Grasso / February 21, 2024

Near the end of Richard Nixon’s first term, the forces of conservatism and reaction were in the ascendancy in America. This public resurgence of “traditional values” was itself a counter-revolution against the turmoil unleashed by the young in their opposition to the Vietnam War and their support for the civil rights struggle, which had swept through America’s streets over the previous decade. America’s traditional power structures did not ignore this radical wave of change; under both Lyndon Johnson and Nixon, the government unleashed all the instruments of the state to try to quash these movements. And many parties on the side of the Establishment within this new generational “culture war” found themselves looking for ways to co-opt and capitalize upon the more superficial aspects of the youth revolution.

Nowhere was this more evident than in mainstream American Christianity. Upon seeing the counterculture’s exploration of new spiritual and numinous experience in defiance of their technocratic Cold War suburban childhoods, Evangelical Christian sects saw that in order to compete in America’s vaunted “marketplace of ideas,” they would need to divert idealistic youth, many of them exploring psychedelics and Eastern religions in search of deeper meaning, back to the bosom of church and pastor. A fusion of hip, Aquarian awareness with the radical promise of early Christianity had already begun to take root within pop culture on stage and screen, as well as within the various churches, communes, and outreach programs that comprised the nascent Jesus Movement. But the big Evangelical preachers and churches who had spent the years since World War II expanding their enterprises by way of mass media were largely outsiders to the Jesus Movement, which had grown from within the nominal grassroots of Evangelical thought, especially on the West Coast. Apocalyptic preachers were reaching out to the young by meeting them where they were: using music, comic books, and other elements of popular culture.

The Campus Crusade for Christ, which was founded by Evangelical candy magnate Bill Bright and his wife Vonette in 1951 at UCLA, had allied with postwar megapastor and confidante of presidents and celebrities Billy Graham (after the Brights’ falling out with ultraconservative Evangelical preacher Bob Jones Sr.). In the first two decades of its existence, the CCC had performed “conversion events” at campuses such as Berkeley that had long been hotbeds of left-wing activism. But by the late 1960s and early ’70s, the Campus Crusade for Christ was toiling in the same vineyards as the Jesus Movement—and reaping many fewer conversions. The old-school Evangelical power brokers were never going to have the broader, hipper, more ecumenical appeal that the Jesus Movement inherently possessed. What the more traditional Evangelicals did have going for them was their access to the traditional levers of media and to temporal and monetary power.

From Bright and his allies came the idea for Explo ’72, a mass meeting meant to bridge the gap between the new Jesus People and their older Evangelical forebears. Explo’s name was “meant to suggest a spiritual explosion,” but also evoked the recent worldwide success of Expo ’67 in Montreal and Expo ’70 in Osaka. Explo ’72 organizer Paul Eshleman, 30 years old at the time of the event, had been a crucial part of CCC’s activities during the late ’60s at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, a campus that was one of the most fervent homes of protest against the military-industrial complex (in the person of Dow Chemical‘s recruiting of students). Eshleman was given the monumental task of organizing a week-long event that Bright envisioned would encompass tens of thousands of college-age evangelists, musical acts, pastoral instruction and networking, and a public relations program that would entice young people across America not only to come to Christ but “To evangelize the world in our generation.”

In The Explo Story: A Plan to Change the World, published soon after the June 1972 event held in the Dallas, Texas metroplex, Eshleman and co-author Norman Rohrer present highlights from the many activities and events at Explo. Bill Bright’s bombastic foreword dispenses with the occasional light-hearted humility of Eshleman and Rohrer’s text, celebrating the worldwide impact of the event. Bright eerily predicts that “Explo ’72 was part of a plan, part of a world-wide strategy dedicated to the fulfillment of the Great Commission by the target date of 1980.” While the entire world did not come to Christ in the next eight years, Evangelicals would elect a President in 1980 who would bring their millenarian dreams of Christian conversion and conquest to the fore of American society.

To be fair to both Bright and Eshleman, the organizers of Explo ’72 did have a lot to celebrate; the event was a truly massive effort. (The final chapter, wittily titled “How God Did It,” is actually about how many individual members of CCC contributed to the event’s success.) While the text does kick off its first chapter by having a good-natured laugh at all of the logistical difficulties that the young participants experienced in accommodations and transportation, the remainder of the book takes up the mantle of Bright’s braggadocious joy. The photos included in the book run the gamut: crowd shots at the nightly revival meetings held at the Cotton Bowl, views of the Explo “campsite” set up for overflow after Dallas-area hotels had been filled (the chapter titled “Mud, Mosquitoes and Miracles” offers clear parallels to the much larger crowd at Woodstock three years previous), and intimate shots of young people singing and shouting praise together.

This foregrounding of the younger generation in the book is a constant. The Reverend Graham, in a press conference with Bright, makes the ironic statement that “Many of the great movements of world history have begun with students.” (Considering the youth revolts in the streets of the West and the Cultural Revolution sputtering to a close in the People’s Republic of China, one wonders if Graham’s evocation of left-wing youth insurgency on campus was wholly intentional.) Explo did succeed in co-opting one aspect of the Jesus Movement—its forays into Christian music. Giants of the Jesus Movement (and what would one day become known as Christian Contemporary music) such as Larry Norman shared the stage with giants of the mainstream: Kris Kristofferson, Johnny Cash, and June Carter. All of them literally went on the record in support of Explo with the 1972 LP Jesus Sound Explosion. The threads of country, gospel, contemporary Christian rock, and old-time religion mingled freely on stages that evoked the new ’70s trend towards massive arena rock tours. Additionally, professional athletes and coaches made appearances to spread “the Message in Muscle.” Dozens of NFL players, current and retired, showed up, including Paul Eshleman’s father “Doc” Eshleman, then-chaplain of the NFL.

But whatever moments of joy and cultural relevance emanated from the Explo gathering, deep down the organizers knew what the event was all about: bringing the “lost sheep” of the Baby Boom back into the fold of conservative Christianity. All throughout The Explo Story, the anxieties of a world that had changed in the blink of an eye over the previous five years are laid bare. Eshleman and Rohrer are assiduous in making sure that the reader knows this gathering was designed to be multiracial and multicultural: “Explo drew the largest number of blacks and other minority groups of any Christian gathering of its kind in history.” Later in the text it is discovered that this “largest” percentage of Black Christians was “[a]pproximately three per cent—about 3,000 delegates—of the Explo crowd.” A frankly patronizing conversion story appears in chapter 4, “A City of ‘One Way!’ Streets,” where a young white woman overflowing with the “spiritual rekindling of Explo” met a Black man on the street who “held up both hands. ‘These are the hands of a criminal,’ he hissed. ‘Can your whitey God forgive me?'” Of course, the young woman evangelist prays with the Black man for twenty minutes, inducing him to release his worries of “selling out my people to believe in a white God,” and another soul is won for Christ.