You Can Only Watch 20 Films for the Rest of Your Life

Features / August 14, 2025

Mike and Kelly believe the Dude really ties the room together. Richard’s a fuckin’ nihilist.

GRASSO: I hate Top Whatever lists.

Not the kind of Top X lists that are based on sales or airplay or objective criteria or what have you, but being asked to come up with, say, a Top 20 Personal Albums or Sports Figures or, indeed, Favorite Movies of All Time. How am I supposed to do that? My opinions on movies can sometimes change during the course of a single (re)viewing or conversation with someone! Also, there’s that whole “putting your intimate aesthetic tastes out there to be judged” thing that I’m constantly afraid of doing. Especially with respect to film, which seems to have one of the most contentious communities online these days. So, naturally, when Kelly asked each of us to come up with “20 Films for the Rest of Your Life,” I was grumblingly resistant. I still don’t know how I ended up being the one who finished his list first!

My process entailed just thinking about the movies I’ve watched most, and picking which ones I would still need to have a copy of in Kelly’s “desert island” situation. Then I filled some of the holes in with oddball personal choices and films that, as I was considering my “bubble” of movies in the low-20s, that I just couldn’t bear to see out of contention. I’m incredibly self-conscious about the aesthetic and genre elements of the movies on this list, but I’m sure I’ll get a chance to expand on and justify my choices in my next turn. Here you go, then: Mike Grasso’s Top 20 Movies of, yes, All Time.

Persona (1966)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii (1972)

Network (1976)

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Apocalypse Now (1979)

UFOs Are Real (1979)

Blade Runner (1982)

Videodrome (1983)

Manhunter (1986)

Goodfellas (1990)

JFK (1991)

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992)

Casino (1995)

Boogie Nights (1997)

The Big Lebowski (1998)

24 Hour Party People (2002)

Inherent Vice (2014)

Mandy (2018)

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

MCKENNA: Jesus Christ. While very much not the first time Kelly has demanded we do something excruciating, he definitely raised the bar with the outrageousness of this one. Once you’re over 50, what is the likelihood of having less than, say, a hundred “favorites” of anything—if you even still like it all? I probably have more than 20 ailments that I’m sort of fond of.

But this weasel-words “You Can Only Watch 20 Films for the Rest of Your Life” phrasing has allowed wily lowlife Roberts to cunningly avoid the inevitable refusal to cooperate that a request for a top 20 would have elicited while, as Mike has pointed out, making the selection even more embarrassingly revealing of the limits of and gaps in one’s own actual tastes. It feels like taking off my jumper at the third year end-of-term disco to reveal the Genesis “Shapes” tee I was wearing underneath it.

Anyway, the older I get, the less “stories” and “plots” and “resolution” feel relevant to the experience of existing, so I’m going to go with films I love and have either seen loads of times or not enough times and which basically put me into a fugue state while also pressing the specific aesthetic buttons inside me that I like having pushed. There are films I’ve loved very much since childhood, like CE3K and Star Wars, that I’d have put in, but I’ve seen them so many times I think I’ve basically internalized them—I don’t think I need to watch them again, they’re kind of part of the architecture of my brain at this point.

But anyway, how about we make it thirty?

This Island Earth (1955)

Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

THX 1138 (1971)

The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973)

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974)

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Eraserhead (1977)

Stalker (1979)

Alien (1979)

The Fog (1980)

Southern Comfort (1981)

Litan (1982)

The Dead Zone (1983)

Manhunter (1986)

Sonatine (1993)

Solaris (2002)

Werckmeister Harmonies (2000)

Dredd (2012)

Evolution (2015)

Petite Maman (2021)

(Okay, great—Kelly’s just informed me that, according to his made-up rules, TV movies aren’t actually movies. Meaning presumably TV dinners aren’t dinners either? That means I can no longer include the film I was planning to include—Journey Through the Black Sun, the amazing Space: 1999 “TV movie” that was made by cobbling together a couple of episodes of the TV show. Fine, let’s just not include one of the greatest human artifacts ever just because, why not. Okay, fuck it, you know what I’m going to include? The 2012 Dredd. So stick that in your pipe and smoke it, brother Rico.)

We all have Alien, right? Right?

ROBERTS: Listen, I don’t know what you guys are complaining about: one of my movies revolves around inept dinosaur puppets. I’ve been laid bare once again. Yes, it’s basically the “desert island” experiment, but in my version you can’t bullshit and say you want Bitches Brew for that last slot when you really want Toto IV (yes, I know, they’re both great albums). As Richard says, this exercise is “embarrassingly revealing of the limits of and gaps in one’s own actual tastes.” That’s the point. You won’t find any Godard or Kurosawa or Altman films on this list not because I don’t admire those directors, but because, if I had to choose, I’d rather watch spiky-haired Kevin Bacon save a small, god-fearing town from dancelessness. If I were in my twenties, my list would look incredibly different; I might even have chosen (bravely, or rashly) 20 movies I’d never seen before. But I just turned 50-something and, you know what?—I want to watch the films that still, after a lifetime of watching films, move me, or simply make me happy.

Think about the list strategically. It’s for the rest of your life! What will you watch when you’re sad? When you’re high? When the holidays roll around? When you’ve got the flu? When you want to believe in magic? When you need to believe that goodness prevails? When you want to visit a future that you won’t be around to see?

These are not the 20 greatest films ever made. These are the 20 films I can’t live without.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

The Poseidon Adventure (1972)

The Land That Time Forgot (1974)

Star Wars (1977)

Watership Down (1978)

Alien (1979)

The Black Hole (1979)

Escape from New York (1981)

Blade Runner (1982)

E.T. (1982)

Mad Max 2 (1982)

The Thing (1982)

Footloose (1984)

The Karate Kid (1984)

Aliens (1986)

Dazed and Confused (1993)

Sense and Sensibility (1995)

The Big Lebowski (1998)

Master and Commander (2003)

You thought Kelly was kidding about dinosaur puppets. Nope.

GRASSO: So first things first, before I get to picking apart both of your lists (just kidding; how could I ever, especially considering the overlap Kelly and I have!), an apologia for my picks (of course): I’m thoroughly and embarrassingly aware of how there are no women directors on my list and how “dudes rock” so many of the films are. I can’t help it. There’s no scenario where I go without watching Goodfellas and Casino for the rest of my life. I’ve watched them, along with JFK, enough times to be able to recite huge wodges of the dialogue purely from memory. If society ever plummets into a Fahrenheit 451 scenario where we need to preserve films using the oral tradition, please assign me these three movies. But yeah, there’s a lot of crime flicks here, psychological thrillers, a fair smattering of science fiction, and big political films (leaving off mid-’70s paranoid stuff like The Conversation, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men, and Three Days of the Condor hurt, but they were all definitely on my bubble). These types of movies are who I am and I can neither deny or excuse it.

So many of my movie preferences were formed in the first quarter-century of my life; as you can see, I’ve only included four films from the 21st century and most of my other picks dwell in the last quarter of last century, the 25 years that overlap with my 20th-century lifespan. These are movies that maybe I didn’t see in the theater when they came out, but definitely caught on TV, cable, or VHS as I became a film buff from childhood into adolescence (thank you again Dana Hersey and The Movie Loft). Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Network, and 2001 are three films I met at a very early age and they will live in my head and my heart forever.

Two directors—Paul Thomas Anderson and Martin Scorsese—appear twice. Ashamed to say that despite Kubrick’s and Cronenberg’s and Lynch’s and Coppola’s inviolable places in my pantheon of auteurs, I only picked one from each director that embodies what I love about their work so much. Maybe I rewatch Blue Velvet or Mulholland Dr. more frequently than I do the harrowing Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, but for my money everything “Lynch” is in the latter, and for that reason it stands alone, much like Videodrome for Cronenberg and Apocalypse Now for Coppola.

The ones I consider “oddball choices” here are where my other interests intersect with film. Pink Floyd Live at Pompeii and Michael Winterbottom’s impressionistic postmodern tale of the Manchester music scene 24 Hour Party People are two of the best films featuring/about music I could think of, and I need some music on my desert island. I could’ve easily included stuff like Scorsese’s The Last Waltz or Led Zeppelin’s toxically self-indulgent The Song Remains the Same, but both really don’t rise to the level of “must-haves.” Low-rent UFO documentary UFOs Are Real, well, I’ve written about the hauntological impact of that movie extensively for Mutants, and it too is a film that repeated childhood viewings made part of, as Richard suggested with some of his leave-offs, my permanent matrix of obsessions. Unlike Richard, I desperately need that cinematic comfort food.

Whew. Richard, tell us a little about your picks!

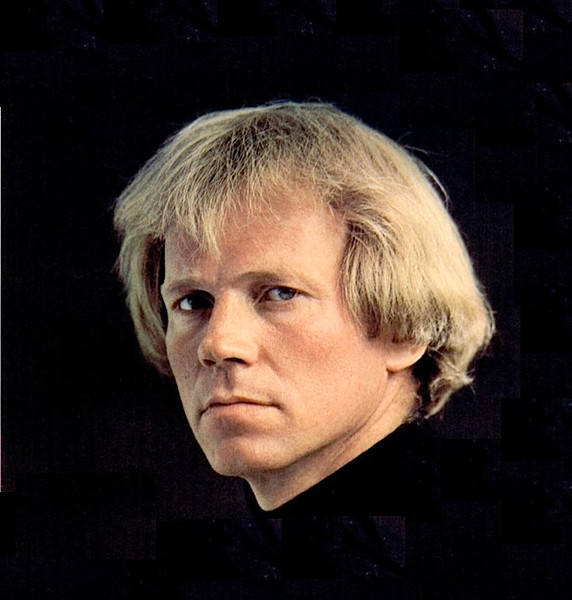

Only Michael Mann could make a dude riding an elevator look like an ecstatic vision. And yet Kelly would rather “cut loose / Footloose / Kick off the Sunday Shoes”?

MCKENNA: Christ on a bike, this is torture. Why are we doing this to ourselves? Coming back to my selection is even more agonizing than choosing the bloody things in the first place. I really don’t need to be reminded that my whole personality is just a lame blend of regressive nostalgist who refuses to relinquish the psychic atmospheres he immersed himself in as a kid and the kind of try-hard insecure idiot who cares so much about the opinions of other people—even the hypothetical other people who won’t even read this—that his decisions are always shaped by trying to impress them. I already know that, I said it before!

Looking at this list again I’d probably change half the films I put in there, but I suppose we have to commit at some point, so fuck it—let the shit film choices fall where they may. It looks like the guiding principle with my list is things that put me somewhere oneiric? I mean, I put This Island Earth, but it could just as easily have been It Came from Outer Space, or Invaders from Mars, or Forbidden Planet: anything that shunts me through the veil that separates us from the dreamworld will do. This Island Earth has a particular appeal for me, though, because it feels to me like a film where the mood is the story, and I suppose that’s kind of a theme that runs through my list. And good to see that we’re overlapping on Manhunter, Mike.

Like I said before, some films that I love I really feel like I’ve seen enough times to make watching them again a bit redundant, and then there’s other stuff that I love and haven’t seen much, or maybe only once, but don’t really have any interest in seeing again. I suppose it’s a bit like the saying “Friends for a reason, friends for a season, friends for life,” which I’ve always (perhaps idiosyncratically) interpreted as meaning that people can be important to you in different but equally valid ways. Some films are friends for a season—I love them but that season’s gone—and others are friends for a reason. Whereas Jason and the Argonauts feels like a friend for life, like I’m entering some sort of eternal mythical dream-space where each visit takes me deeper into something? Myself? The collective imagination? I appreciate that’s a bit bombastic when talking about a film whose main draw (for me) is the stop-motion skeletons, but much as I love, say, Pasolini’s Medea or Cocteau’s Orphée, just to give two examples of other films that engage with the mythical, I’m not compelled to rewatch them in the same way. Is it just nostalgia for the me that watched Harryhausen a shitload when I was a kid, or does Jason and the Argonauts genuinely access some different part of my brain? Does it even matter? Probably not.

Choosing Alien feels pretty stupid—it’s one of the most famous films in the world, and it’s been franchised into absolute shit. And yet it’s still something that affects me in a strange way every time I watch it. I have my own history with it, but it also feels fresh every time. Mythical, you might say.

Anyway, enough of the babbling, let’s get down to what’s important—Footloose, Kelly? Are you fucking kidding? I mean, I’ll give you Sense and Sensibility, I could watch Hugh Grant writhe with discomfort all day, but Footloose? Was proposing this feature just a way for you to indulge some weird public humiliation fetish that risks taking blameless Mike and me down with you? Explain yourself!

ROBERTS: Like both of you said, some of these films are here because of how much they affected me when I was young and impressionable, before my core being solidified. But then, why Footloose and not a dozen other films (WarGames, The Goonies, Legend, Tron, Red Dawn) that obsessed me when they came out in a way that Footloose didn’t? Plus, dancing is stupid! I think it’s because, underneath all the ‘80s (fun) silliness, there’s something incredibly authentic to me, a suburban only child who grew up in the shadow of Reagan, about these small-town teenagers resisting an oppressive and repressive adult regime at a time when young people were patronized, scapegoated, and exploited—punished, in a way, for the sins of the counterculture. (E.T. is on here for exactly the same reason). It still gives me chills when Ren makes his case at the town council for having the school dance, and when Lithgow gives the sermon asking everyone in the town “to guide them in their endeavors.” There’s a mythic (this word keeps popping up, doesn’t it?) or allegorical quality there, at least to me. To answer your question, Richard: I need it. In a way that I don’t need another movie I love, Over the Edge, probably the best movie about teenage rebellion ever made.

At first I thought I didn’t need Star Wars because I’ve seen it so many times and essentially absorbed it into myself—but I can’t stand the thought of it not being there. So I do need it. But why? And why Star Wars and not the better sequel, The Empire Strikes Back? I could go on and on in this way, questioning each of my choices, trying to make sense of this list. But the word need is pretty basic, and that’s what it comes down to.

Mike, you have to explain Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii to me. I love it and watched it religiously as a young guitar player, but wouldn’t the soundtrack suffice? Are you that big of a Floyd fan?

And Richard, why Southern Comfort? There are much better Walter Hill movies, and this one is kind of a rip of Deliverance, no?

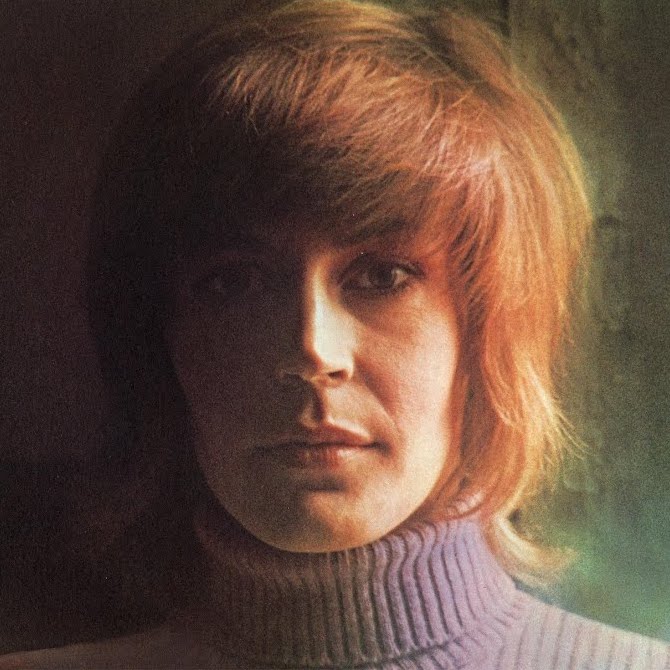

Richard was the only one to honor the great Tarkovsky. Too bad he betrayed the auteur’s memory by also including… the Solaris remake?

GRASSO: Richard: Alien definitely is on my bubble and you should feel no shame about selecting it whatsoever; for Ridley Scott representation, it and Blade Runner are a tossup and, honestly, I feel like Blade Runner edges it out purely thanks to the immortal musical efforts of one Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou at his absolute fucking peak. I totally get what you’re saying about This Island Earth, too: it may be one of the thematically hokier entries in classic ’50s scifi, but visually, even up against the often trippy Forbidden Planet, it’s a phantasmagoria, isn’t it? Honestly, most of your films are visual tours de force: The Fog is probably the most memorably-shot Carpenter next to Halloween, and Manhunter stands head and shoulders above most 1980s thrillers and most of Michael Mann’s already formidable corpus. (I still feel like my jury is out on your abiding love of The Dead Zone, but its chilly, detached vision as you’ve described it now seems like a harbinger of Cronenberg’s late-career turn into the cold, clinical, and cerebral.) As for mythic echoes, I get what you’re saying about selections like Jason and the Argonauts and Alien—and of course you managed to expertly dovetail Manhunter with Dragonslayer in the Mutants book. Now I’m considering THX-1138 as an example of the hero’s journey long before Lucas met Joseph Campbell and, God help me, it fits!

And Kelly, the middle of your list of picks—from Star Wars to Aliens—really does constitute what I would call the late ’70s/’80s “mall movie theater core curriculum,” maybe with the addition of stuff like Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Night of the Comet. The Thing is the kind of choice I see on a list and smack my forehead as to how I left it off (probably the easiest explanation is that I’m not the world’s hugest John Carpenter fan; I know, I know). I probably saw E.T. three or four times in the mall movie theater when I was a little kid. Footloose and The Karate Kid are a pair of pop culture touchstones of my youth, although those two are more likely movies I internalized from repeated cable viewings. Underdog stories—boy, we really did love those in Reagan’s America, huh?

As for my ranking Live at Pompeii, well, I mentioned The Song Remains the Same as its chief competitor because basically I need one “heady” music film on the list that I can get stoned and zone out to on my desert island. I probably like Zeppelin’s music a fair bit more than Floyd’s, but Pompeii‘s mix of sound and trippy, ancient visuals is the winner over Zep by a nose.

The outliers on each of your lists I would love to hear more about: Richard, I love Herzog but I would never put Kaspar Hauser on my list of favorites of his. Also, I’ve never seen Werckmeister Harmonies but loads of people swear by it as superb. And Kelly, I am gonna give you shit for Sense and Sensibility just because I’ve been lassoed into watching countless British adaptations of various Regency novels of manners by my goodly spouse and have hated all of them. Also, I’m kicking myself now for leaving off Dazed and Confused, speaking of good movies to watch stoned.

MCKENNA: Kelly, why the fuck are you trolling me about Empire Strikes Back being better than Star Wars? Why? We’re better than this. We’re more mature than this. We’ve read clever books, we’ve written a book (that nobody read): we don’t need to spend our time trying to provoke each other with self-evidently foolish positions about bloody Star Wars. That said, fuck you, because Empire Strikes Back is the turd that Star Wars shat out (Hoth and Bespin sequences excepted)!

Okay, now I’ve got that off my chest, I actually love both of your lists. In the sense that I think it would probably be possible to reconstruct the pair of you bodily from them like Jeff Bridges from a hair in Starman, or Oddbod Junior from a toe in British comedy horror masterpiece Carry on Screaming, which I’m now kicking myself for not including (even just for Fenella Fielding). And why have none of us included Starman, come to think of it? I hate doing this.

I get what you mean though, Kelly, about “needing” certain films. It’s as though they have a language built into their interiors that you need to run through your speakers now and then, the way you sometimes need to play back experience in your mind to remind yourself of how you got to be who you are. Calling it “nostalgia” is, I think, reductive (don’t worry, fans of bloviating, I have a long and tedious article on this very concept in the pipeline)—it’s more like refreshing your operating system, or sharpening a knife.

Mike, I want to thank you for the Alien support and also for locating THX-1138 as an example of the hero’s journey—this is exactly why we need that Grasso laser insight here at WATM. Because, let’s be honest, Roberts and McKenna are not providing it: in classic Gen-X style, vibes is all we’ve got.

Anyway, to answer you two’s questions, I don’t really know why Southern Comfort as opposed to Hill’s other films. I’m kind of a one-note person, and I think it’s the same thing I’ve already said: there’s something about how sleek, reductive, even derivative, it is that takes it into the landscape of the mythical. Plus, it’s basically like four other films that I like rolled in one. And Mike, Kaspar Hauser‘s a film I saw around the same time I saw Truffaut’s The Wild Child, when I was probably eight or nine. They used to show stuff like that in the early evening on BBC2 in the ‘70s, incredibly. Both films affected me very deeply, and I didn’t know which of the two to choose, but decided on Kaspar Hauser for the soundtrack and for its pervasive mood of intense outsiderness. Come on, we all feel like we’re seeing stars in the daytime occasionally and don’t know how to behave in polite company! There’s a case to be made, I suppose, that Werckmeister Harmonies is one of Bela Tarr’s “easier” films, which I suppose in a way it might be, but despite its gloomy themes, watching it in its entirety always feels very… healthy? It feels like you’ve been through a ritual cycle of humanity that in some way is renewing? To be honest, that might be the unifying thread running through all my choices.

I feel a bit shit but apart from fucking Footloose—insert facepalm emoji—I don’t really have any questions about either of your lists. Like I say, I feel like they’re authentic representations of the pair of you. What were the films you two nearly put in but didn’t, and why?

Ridley Scott is the most represented director on our combined lists. John Carpenter is second.

ROBERTS: That’s an interesting question, Richard, so I’m going to give everyone five more selections. Now you can watch 25 films for the rest of your life. See mine below, with notes.

You make a good point about Mike providing the insight here, because I had no idea how many of my picks are in fact about the underdog against all odds. Ripley, Max, Luke Skywalker, Snake Plisken/R.J. MacReady, Ren McCormack, Daniel LaRusso, even the rabbits in Watership Down! Jesus. It certainly says something about me. It’s Samuel Beckett, I guess—“…you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on”—but mixed with some… John Wayne? Irish pessimism meets American exceptionalism?

Mike notes that many of Richard’s films are visually compelling, which is true, but they have something else in common: they’re about people/beings who don’t fit in, who are overwhelmed by a “reality” that is often alien, irrational, and unstable. The Man Who Fell to Earth is the obvious example, but it’s also the core theme of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, and you can make a good case for Eraserhead (the mood perfected in Lynch’s next film, The Elephant Man), Manhunter, The Dead Zone, Southern Comfort, Evolution, THX 1138, et al.

With Mike, it’s the intersection of media, politics, and conspiracy. He’s obsessed with the screen, its ability to reflect and/or remake reality. Network and Videodrome are explicit satires on television, but screens have a profound role in many of these other films: the projector and projected images in Persona, the home videos in Manhunter, the TVs that reveal Devil’s Tower in Close Encounters, the prolific “evidence” in UFOs Are Real (mostly photographs made to appear as video), the ubiquitous Zapruder film in JFK. Another thing that’s interesting about Mike’s list: only one of his last 10 films—that is, every film from 1990 on—takes place in the present day. All others are interpretations of the past—the late ‘60s through 1990, when The Big Lebowski takes place. (You could argue that the outlier, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, actually falls into the same category, given the ambiguity of time in the film and its ironic ‘50s mood and aesthetic.) This is our area of concentration at WATM, yes, but there’s something else here. A few of these films posit or suggest an alternate history—what kind of world might we have had if Rick and Cliff had killed the Manson Family? If a government conspiracy to kill JFK had been proven?—but most are tragedies that illustrate why we can’t have that better world: big dreams momentarily fulfilled but ultimately and irrevocably corrupted, mostly by greed.

In short: you are both far more complicated than me.

As for Sense and Sensibility, Mike, you have to remember that I was strictly a Western Canon guy well into my thirties, and Jane Austen is a favorite. This is a faithful and beautifully acted and directed adaptation of my favorite Austen novel, and it’s got a big, fat, happy, romantic ending. Every once in a while, I need one of those.

The Magnificent Seven (1960) (I love Westerns, and this is my favorite, although 1972’s The Cowboys and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly are extremely close. It’s about… underdogs.)

The Time Machine (1960) (George Pal’s best.)

Jason and the Argonauts (1963) (Harryhausen’s best.)

Outland (1981) (Yet another underdog story, an early sci-fi noir with one of my favorite monologues of all time.)

Conan the Barbarian (1982) (The greatest fantasy action film ever made [sorry, Peter Jackson], and Milius’s finest hour. It’s a retelling of Apocalypse Now, believe it or not.)

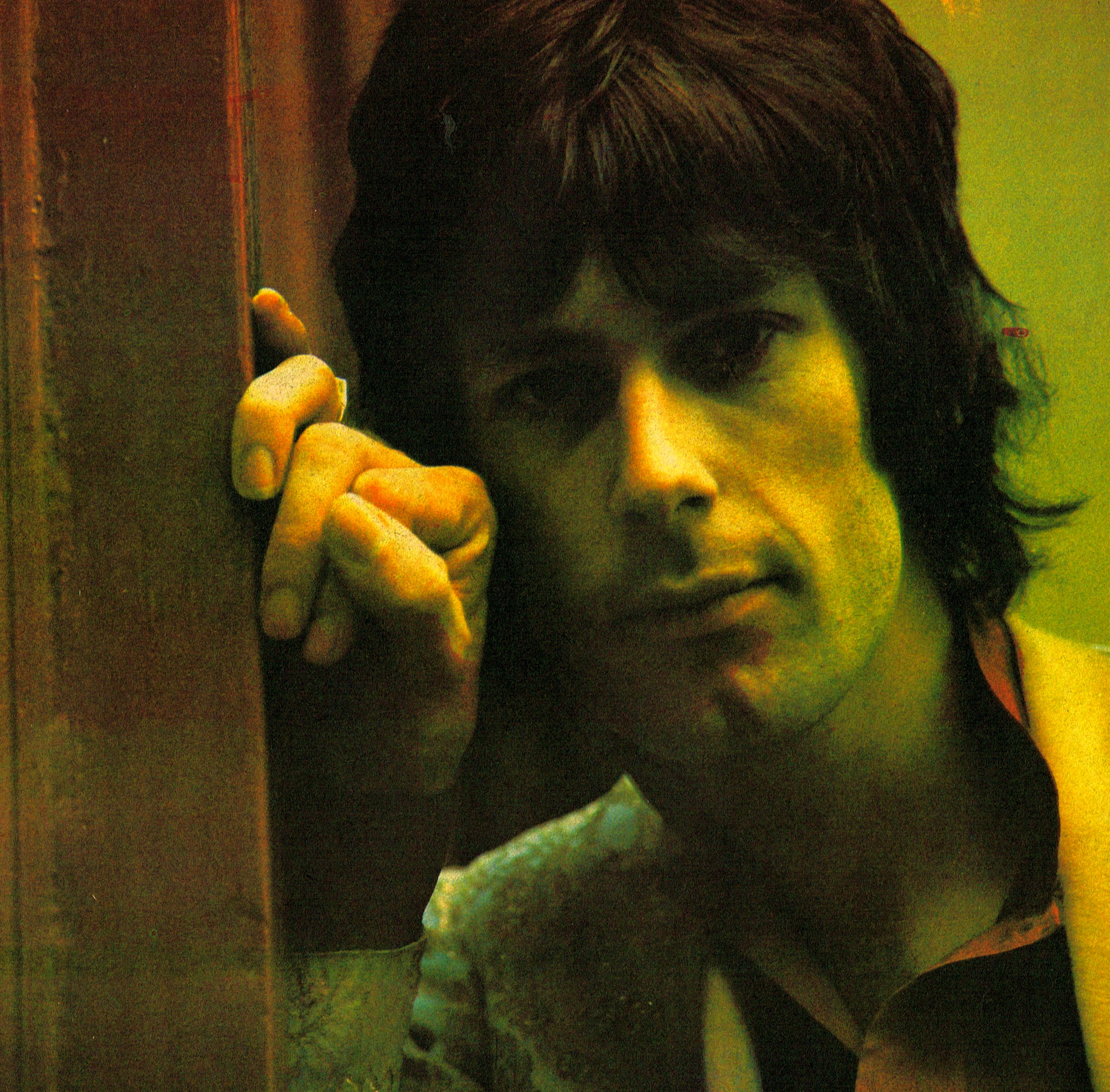

Not even Cliff can save us from our psychotic past. Also, Mike is the only one who repped Tarantino.

GRASSO: Yep, you got it in one, Kelly: paranoia, television, and nostalgia, my three great interwoven lifetime obsessions. I can’t think of one of my movies that doesn’t fit neatly into one or more of these themes. Did you design this seemingly fun and innocent critical assignment as a psychological test? Oh wait, maybe that’s my paranoia talking again. To get Mythic Outsider Richard and Paranoid Hauntological Mike to lay bare our entire psyches in a list of 25 movies… that’s pretty damn devious.

Speaking of devious, paranoid personality tests, one of my five bubble films fits that bill perfectly:

The Godfather Part II (1974)

The Parallax View (1974)

The Ninth Configuration (1980)

Slacker (1990)

Uncut Gems (2019)

I may have agonized over these five as much as the previous 20. I think you guys may have seen an earlier version of this list in our shared document that had five completely different movies! The Godfather is, we must concede, a perfect movie, but I like Part II‘s overstuffed historical sprawl (and oblique nods to CIA-Mob parapolitics in Cuba and elsewhere) a tiny bit better, not to mention that John Cazale’s performance as Fredo beats any other performance in Coppola’s trilogy—and perhaps in the entirety of the 1970s—handily. I chose The Parallax View over All the President’s Men and Three Days of the Condor primarily for its higher quotient of Weirdness and its direct invocation of the American intelligence community’s complicity in the wave of domestic political assassinations in the 1960s. On that note, I was thinking Winter Kills (1979) for a while as well, but to my mind William Peter Blatty’s The Ninth Configuration is a better parable about how all our imperialist wars blow back onto the domestic front. I pondered Dazed and Confused for a bit until I realized that Richard Linklater has an even more rewatchable film in Slacker, and one that speaks to me far more personally (and generationally). And finally, one of the two movies I saw (along with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood) in a theater before COVID hit, Uncut Gems, a great gritty New York City crime yarn in the tradition of my Scorsese and Coppola selections with a killer electronic score from Daniel Lopatin that rivals the aforementioned Vangelis soundtrack for Blade Runner.

One of my favorite parts of conceiving the Mutants book was coming up with all those great double features that may not have looked like they worked on paper… at least until we went on about them for three to five thousand words. I feel the same about these lists: they each offer a curriculum in filmmaking and film critique where the constituent movies inform, illuminate, and complement each other. One thing’s for sure: there are a bunch of films on Richard’s list I’ve never seen before as opposed to Kelly’s, where I’ve seen 23 or 24 of them. And just one more snipe here as I close things out, Richard: Soderbergh’s Solaris instead of Tarkovsky’s??? I can’t believe I missed that! What?

Linklater times two.

MCKENNA: It’s a fucking rocker, Mike! Obviously takes a very different tack to the Tarkovsky version (which I do love, but have to admit that—shallow fool that I am—overfamiliarity with Italian comedy Fantozzi has put an aesthetic crimp in for me, for reasons that will become obvious if you see it), but it’s a powerful, moving film about loss, love, and the nature of existence that captures the sadness and strangeness of the book, is aesthetically genuinely beautiful, and has a great cast and great (and much ripped-off) soundtrack by Cliff Martinez. And yes, it is another oneiric, unreliable world whose nebulous laws a cipher of a person tries to come to terms with—thanks for reducing my whole personality to this, Kelly. Anyway, along with Sex, Lies and Videotape, I think it’s Soderbergh’s best film and best real shot at movie immortality—it has such a beautiful elegiac mood. I think it suffered from people thinking it was trying to be a remake of the version by Tarkovsky—around whom an unfortunate aura of secular sainthood has ossified over the decades—as opposed to just a different attempt to adapt the book. But apparently Stanisław Lem hated both versions, which is pretty much standard Stanisław Lem.

Anyway, talking of realizing you’re a caricature, here’s my five extras. Note Orson Welles’s The Trial—how’s that for on the nose?

Mon oncle (1958)

The Trial (1962)

Judex (1963)

Aliens (1986)

American Movie (1999)

Ack, that was even more grueling than choosing 20. My main takeaway from this is how frustrating it is. There are so many films I love—some of which are absolute excrement—but when you sit down to try and create a canon, it’s hard not to get a bit stuffy. Plus, my memory’s atrocious: as soon as we post this, I’ll remember the films that I should have put in. Ah well, at least this nightmare’s nearly over.

Without wishing to get all solipsistic, it’s odd seeing our tastes laid out this cleanly and realizing the kind of triple Venn diagram the three of us form, with at its central intersection… I don’t know, a UFO? Where is it that we all overlap?

ROBERTS: I think the Solaris pick is clearly the worst of the lot—the only explanation I can think of is that Richard has a thing for Clooney, who has done roughly 800 better movies (including Soderbergh’s Out of Sight, which almost made my list). On the other hand, including the great American Movie—a riveting and hilarious documentary charting the life and death of the American Dream—in your final five is a stroke of genius. I kind of thought we would have more picks in common, to be honest! Mike and I have three (2001, Blade Runner, and The Big Lebowski), Richard and I have three (Alien, Aliens, and Jason and the Argonauts), and Mike and Richard have only one (Manhunter). The three of us? Womp womp. Zero! I blame this on both of you, because how could any mutant not include, at the very least, 2001, Alien, and Blade Runner? Well, as we’ve discovered, there’s no accounting for taste.

Is there a common theme? What’s the overlap? I think a UFO is close. The Stranger? The Visitor? The Outsider? I think “not belonging” is not exclusive to Richard’s list. From my out-of-town underdogs to Richard’s unquiet wanderers to Mike’s criminals, searchers, and bums, it’s clearly a condition that we all share. And a condition that compels us. And possibly renews us? (Speaking of compulsion and renewal, I’m surprised no one chose Logan’s Run!)

The second guessing lingers on. I swapped The Time Machine for Stalker at the last minute. Should I switch them back? I’ve got so much drama and so little comedy—what can I take out to get Midnight Run in the lineup? Or The Bad News Bears? Or The Nice Guys? Or the great Sullivan’s Travels, about why movies move us in the first place? Do I really like white people dancing as much as I think I do?

Everybody relax. There’s no need to panic. We can watch any of these movies at any time. We don’t have to choose. It was just an experiment. It doesn’t mean anything. We’ll forget it ever happened…

” and “WAR SUCKS” written on the wall.

” and “WAR SUCKS” written on the wall.

The Possessed

The Possessed

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

“Dear Diary”

“Dear Diary” “The Tale of the Giant Stone Eater”

“The Tale of the Giant Stone Eater” “Enigma”

“Enigma”

“Heartache Avenue”

“Heartache Avenue” “Eve of Destruction”

“Eve of Destruction” “Angie Baby”

“Angie Baby”

“Excerpt from ‘A Teenage Opera’”

“Excerpt from ‘A Teenage Opera’”