A Year in the Iso-Cubes: The Mutants Recap 2020

2020 in action

MCKENNA: Christ on a bike, it has been a year. Who would have imagined back when we started 2020 with a frivolous piece on little plastic spacemen the grim turn things were about to take? And to think, back in a previous end-of-year mutants communiqué, we were hubristic enough to say that 2018 had been punishing, jejune fools that we were! 2020 didn’t like that and decided to show us what punishing really meant: an appalling bastard physically, mentally, and financially that has put immense numbers of people through nightmarish shit. So what better way to indulge in a bit of propitiatory magic in the hope of a better 2021 than by quickly listing a few of the gems your faithful muties have been fortunate enough to find embedded in the continent-sized turd that has been the year? So Mike, Kelly—what have you two stumbled across in the last twelve months that’s given you a glimmer of optimism?

GRASSO: Richard, first things first: when Jenny and I were going through our own presumed COVID infection back in the spring, one of the things that kept me going was chatting with you early in the mornings, whinging about symptoms, lamenting my suddenly swiss-cheesed brain, worrying about… well, nearly everything. So friends have absolutely kept me going this year, and having you and Kelly as comrades and creative partners for a fifth year has been the lifeline that’s largely kept me going.

Like I may have mentioned, much of everything before our recovery in about June is a bit of a blur, sadly. I did stay sane like many people during the first months of the pandemic by watching, yes, Tiger King, which, by the time it was over, got me wanting to watch an earlier, much better Netflix documentary on the tension created by the collision of cultic belief with American capitalist culture, Wild Wild Country. Both of these, though, paled in comparison to the recent release of Heaven’s Gate: The Cult of Cults on HBO Max, a terrific and nuanced look at the individuals who found themselves so damaged by a society that denied them wonder and companionship that they marched off to their deaths for beliefs that seemed insane to everyone outside the group. People were talking about it around the election for precisely the wrong reasons, I found.

Honestly, though, I haven’t had the attention span for much visual media this year. I’ve been doing far more reading and listening. I’ll start with Carl Neville’s fascinating novel of a sideways Earth where an out of control right-accelerationist America faces off against a mostly-Communist rest of the world (including the UK), Eminent Domain. Its deep, detail-packed examination of a “utopia with dystopian characteristics”—a largely post-scarcity “People’s Republic of Britain” where a 1990s revolution against the CEOs and toffs has allowed an ostensibly classless technologically-driven society to flourish—is a political thriller, a spy novel, an exploration of alternate-history culture and art, and in the character that I identified with most—a young American college student who falls in love with the PRB thanks to its cultural products, art, and music—a simultaneous celebration and warning about falling in love with a place you’ve never been. It changed my life in a lot of ways and I’m unimaginably proud I got together with Carl to talk about it back during the summer.

ROBERTS: A blur is right. It’s almost like I’m existing in somebody’s demented time-lapse photography experiment. These (so far) nine months have been hard and they have certainly changed my life—the extent of that change won’t be clear to me until some sense of normality (what does that word mean anymore?) reasserts itself (or my mind inserts it). With a full-time-plus job in a public university health system and two kids at home who are deeply bored and sometimes furious at the inadequacies of Zoom, I haven’t had a hell of a lot of time or energy for discoveries. But I did re-watch a lot of disaster movies, a genre we subsequently (and rather angrily, on my part) wrote about here.

And we did get some great news in 2020: we signed a contract with Repeater to do a book exploring the themes of reaction and resistance in American film from about 1967 through 1987, and it’s been a lot of fun, as well as a welcome distraction, watching so many films from the era and finalizing the chapter list with you guys. It’s also been really hard, because we have no choice but to leave out so many movies we love and admire. I’m really excited about the final list, though, a mix that’s heavy on genre but also includes a few blockbusters, a couple of documentaries, some exploitation classics, and some absolute gems that have all but disappeared from the public eye. The idea is that each chapter will pair two films that may not have much in common on the surface, but connect profoundly on a deeper level.

This project, as well as the videocasts we’ve done, has gone a long way in keeping me sane.

MCKENNA: Yes, having you two to shoot the breeze with has been good—well, those of you two that aren’t a grumpy, monosyllabic Californian. Naming no names. But this year’s definitely brought home how fortunate I am. Work’s been tough but at least there’s been some, which is more than a lot of people have had. I was sick in March—fuck knows what it was but I’ve never had such weird symptoms (annotated list available on request—really). It only lasted a week, but I was still in a weird state when it finished, because work was at a complete standstill, I spent it in bed, and for some reason it seemed to make sense to devote the time to watching or re-watching a lot of Bela Tarr films. At the risk of sounding a bit precious, it was an oddly therapeutic experience that I’d recommend, if you’re lucky enough to have the time. And even though I’m sick to the back teeth of Lovecraft, have had enough Nic Cage to do me for the next few decades and never had much time for Richard Stanley in the first place, I actually found myself quite enjoying 2019’s The Color out of Space.

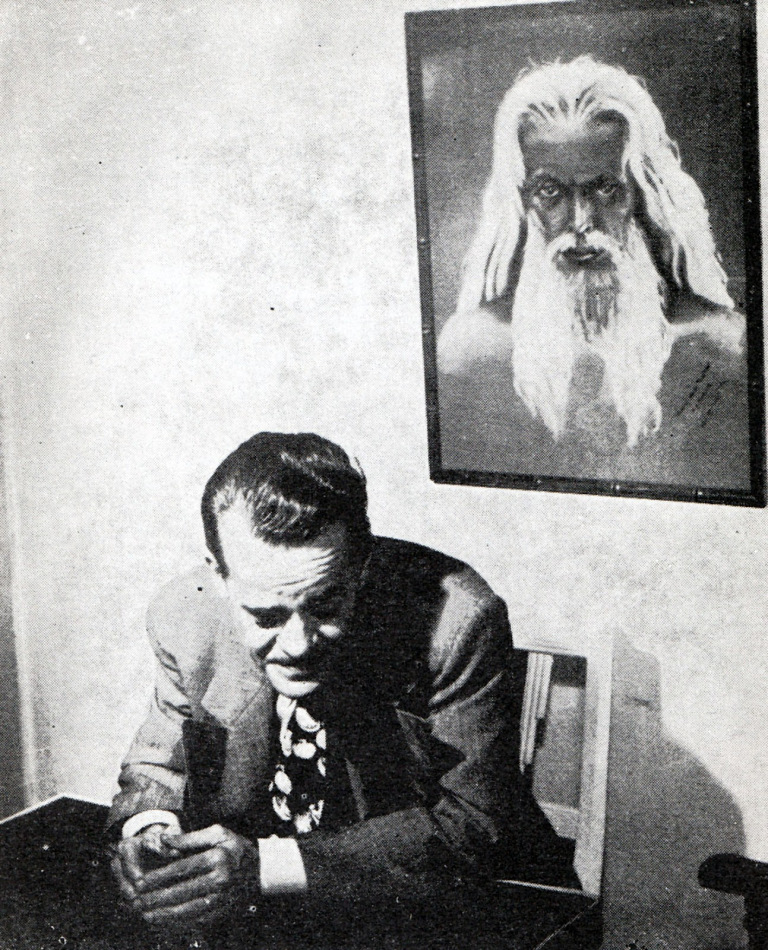

Despite the numbing effect of events, one thing that did make a big impact on me was James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art. There’s so much beautifully rendered art around nowadays, but (and it may just be because I’m getting older) it often seems a bit too perfect—so intimidatingly slick that it can come off as strangely impersonal and unaffecting. That’s not the case with Cawthorn’s stuff—it’s like getting zapped with a cattleprod. I read John Varley’s Gaea trilogy, which I started off thinking was everything I dislike about SF but which turned out to be a lot that I love about it, and, prompted by the website Science Fiction Ruminations, I also read Nancy Kress’s brilliant Alien Light, Suzy McKee Charnas’s brilliant Walk to the End of the World, and finally read some Tanith Lee, which was even better than I’d been hoping since I first meant to read her in 1984.

Music-wise, I fell in love with Fushigi, a 1986 album by Akina Nakamori, Caterina Barbieri’s latest, 2019 Ecstatic Computation, which is just as great as its predecessors, and Yasmine Hamdan’s Arabology (after a tip off by fellow mutant Daniele Cassandro). And of course, a shitload of Hawkwind, after a review copy of Joe Banks’s brilliant Hawkwind: Days of the Underground (review on its way, but in the meantime Joe has written us a great article on the band) spurred me to pull out all my old Hawkwind records and blast myself into the cosmos.

GRASSO: I remember finding myself, immediately after recovering from COVID, really needing music on a near visceral level, spending hours listening to NTS Radio and ordering countless vinyl and DVD compilations from Numero Group, getting into micro-genres and musical scenes I’d never really delved into before. That died off somewhere in the autumn, as I began to mourn what really always attracted me to music, and that is the communal experience of listening and talking about it, which didn’t translate into my isolated life all that well. (One of the exceptions was listening to mixes made by friends and artists I love, but I’ll come back to that in a bit.)

But there was one musical experience in that very difficult autumn that did evoke a sense of community, and that was the release of Oneohtrix Point Never’s semi-eponymous masterpiece LP Magic Oneohtrix Point Never. Given the fact that I was already acquaintances with quite a few fans of Daniel Lopatin’s work, getting to share the experience of listening to and diving deep into the themes and symbolism around this intensely personal album was a delight. Lopatin has always acted as a theorist of nostalgia and media history, and on this album, he uses the conceit of a single day on old-school terrestrial radio, replete with “dayparts” aimed at distinct audiences and demographics, to explore his own career obsessions with the bits of our lives that fall through the cracks of a lifetime bombarded by media. Lopatin’s obsessions around our once-mighty collective pop culture monoculture, its historical fragmentation, and its digital afterlife spoke to me in a year where our collective isolation grew more grim:

“There’s a kind of thesis in [album closer “Nothing’s Special”]. It was a really rough fucking year and it’s been hard for everybody. Something that’s always given me a lot of solace when I’m in a funk is that I notice that I’ve become disenchanted. The thing that can kind of re-enchant me very quickly when I get there is to remember that—like the Philip K. Dick quote said—everything is kind of divine, and everything is interesting, including the stuff between the dials. The noise.

Honestly I did find myself revisiting what you might call media “comfort food” at various points in 2020; I did a complete re-read of James Ellroy’s Underworld USA trilogy and did (er, multiple) rewatches of my favorite Scorsese films—Goodfellas, Casino, and new entrant to the Scorsese pantheon The Irishman—all those tales of white men behind the scenes in the shadows acting badly, those paeans to what Mark Fisher called a “desensitization [to] capitalist realism.” Somehow those old-fashioned, bloody, up-close-and-personal brutalities and cruelties seemed easier to take than the impersonal mass slaughter going on outside our quarantined walls. At least in a Scorsese film or an Ellroy novel you (might) get to look in the eyes of the guy who kills you.

One other old favorite author who surprised this year was Don DeLillo, whose efforts in the ’10s have become almost like prose-poetry: spare, evocative, sketching the edges of our collective collapse. In his slim but powerful 2020 release The Silence, he imagines the loss of our digital commons on possibly the most media-laden holy day of our American calendar: Super Bowl Sunday. Given the dislocations that coronavirus has wrought on all our senses of time and place (especially in relation to using professional sports to orient ourselves in our yearly cycles and how badly COVID scrambled these collective rituals), I found DeLillo’s haunting novella to be both a valedictory for his own career and for an older world of media and parapolitical action that he has helped explain and explore.

But mostly what got me through 2020 were my friends. As acutely painful as it was for me to be physically separated from those friends for a full year, they invariably kept me sane, safe, solvent, and prevented the worst of the demons from knocking at my door. Whether it was gathering online to play Among Us (I have lots of thoughts on why a video game based around betrayal and suspicion became the year’s biggest hit) or just hanging out in those cursed Zoom boxes, without this minimal level of contact I would have surely lost my mind completely. I started a new tabletop RPG campaign online this year, set in the Weird Seventies, and my players have knocked me out time and time again with their own worldbuilding, character development, and exploration of the game’s themes that have been for me much like a magickal Working. This includes, yes, a mix of psychedelic rock, funk, folk, soul, and Motorik music from ’69 to ’73 contributed by player and comrade Leonard Pierce that was a delight to discover and listen to over and over this year. So thanks to the URIEL team. And yes, the planning and writing of the Mutants book (in addition to the Repeater media channel I’ve been working on) has me excited to throw myself into new projects in 2021. So to everyone who’s stuck with us through a once-in-a-century calamity, who’s submitted their own thoughts to our pages, who has shared or commented on our pieces during this difficult time—thank you, yet again. You’re the reason why we keep at it, why we keep plugging away.

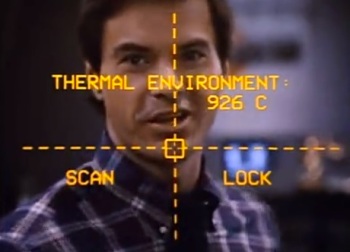

ROBERTS: When I have had a couple of hours to myself, I’ve been rewatching a lot of stuff from the late ’80s and early ’90s, starting with Predator and Predator 2, inspired by Alex Evans’s great piece on the first one. And you know what? I really like 2010’s Predators too. Everybody says Adrien Brody was miscast, but that’s bullshit. He’s great in it. He’s great in everything and people are always saying he’s miscast because he doesn’t look like Brad fucking Pitt. I also love 2004’s Alien vs. Predator—no, I will not be taking comments at this time. From there I revisited a really enjoyable Predator/Terminator rip-off called I Come in Peace (1990), starring my man Dolph Lundgren and, ahem, Brian Benben, who many of you will remember from HBO’s long-running series Dream On. It’s certainly nothing you haven’t seen before, but the chemistry between Dolph, the renegade cop, and Benben, the by-the-book FBI geek, is great, and the evil alien (Matthias Hues) shooting tubes into his victims’ brains to suck out the endorphins (an addictive drug on his home planet) is a nice touch.

Another buried treasure from that high-’80s period is Cherry 2000. I saw it when it came out on video (it did not receive a theatrical release in the US) and didn’t remember much, but it’s got a lot of spirit, and the plot is, er, unique: in 2017(!), a businessman’s sex robot shorts out, and he is so in love with it/her (a Cherry 2000 model) that he hires a tracker (human tough gal Melanie Griffith) to take him into Zone 7 (which turns out to be a destroyed Las Vegas) to find and bring home a replacement. I am in no shape to take on the sexual politics right now, but the film is really colorful and uses a lot of kitschy design elements from the ’50s and ’60s to describe its post-apocalyptic setting, there are some excellent action sequences, and supporting turns from Tim Thomerson (the bad guy, who ends up crucified on a Las Vegas casino sign) and legend Ben Johnson (Shane, The Last Picture Show) make up for the stilted performances of the leads. Director Steve De Jarnatt also directed Miracle Mile (1988), another low-budget cult classic that I watched again and still love.

Aside from research on the book, I’ve read literally jack shit this whole year. My mind can’t do it. Music is an endless loop of the Charlie XCX channel (apparently there is something called hyperpop, and I dig it), New Age ’80s ambient, and anything that resembles the ’80s output of Toto, Rick Springfield, and The Cars.

MCKENNA: I Come in Peace is a fucking rocker, on that we can all agree. And I also agree that Adrien Brody deserves more credit, not least for being one of the few credibly punk faces in a film (Spike Lee’s 1999 Summer of Sam). Anyway, as Mike has so eloquently put it, thank you on behalf of all of us to all of you who have taken the time to read We Are the Mutants this year and anyone who’s supported us in any way, whether by contributing or by commenting, or retweeting, or forking out cash, or whatever—it really is much appreciated. And while I’m at it, thank you two for putting up with me too! With so many going through so much shit, wishing anyone “Happy New Year” sounds a bit empty, but fuck it, Happy New Year anyway!

Snowbeast

Snowbeast

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art