Alex Adams / January 31, 2022

As Godzilla walked away into the sea in the closing shot of Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), Japanese film studio Toho seemed to kiss their bellicose lizard goodbye forever. After fifteen explosive (and increasingly audacious) films over the course of 21 delirious years, the curtain finally fell and the lights finally came up. But of course, Godzilla is immortal: after nine long years, Toho resurrected the creature for Godzilla 1984, a thirtieth anniversary blank slate follow-up to the 1954 original. Also known as The Return of Godzilla and simply Godzilla, Godzilla 1984 is what we would now call a reboot: part remake, part sequel, a fresh start that retrieved some things from Godzilla’s past while discarding others.

And it discarded a lot. Every character and event—every wacky monster, every alien invasion—featured in every previous sequel, from the often-overlooked quickie follow-up Godzilla Raids Again (1955) to Terror of Mechagodzilla, was unceremoniously chucked in the bin. Retrieved: the aesthetic restraint and doom-laden tone of Ishiro Honda’s 1954 original. Godzilla was back, and it was mean. This new iteration, the last of the Cold War period, is something of an outlier in the Godzilla canon: stylistically distinct from the movies that precede and follow it, with a unique monster design and a feel all of its own. But it is also an interesting oddity among pop culture of the time, because the movie shows the Soviet and American nuclear powers, usually at one another’s throats, cooperating to eliminate an existential threat bigger than either of them. The film also reflects with unusual frankness on Japan’s geopolitical position as a minor power forced to stand up to both the US and the Russians, and, much like other high-profile sci-fi of the age, it is a powerful warning about the perils—and futility—of nuclear confrontation. A Godzilla movie of unusual sobriety, Godzilla 1984 tells us a lot about Cold War Japan, and the film’s Americanization as Godzilla 1985 a year later tells us perhaps even more about the politics of Cold War cultural production in the United States.

Close to the Brink: Godzilla 1984 and Nuclear Confrontation

Godzilla 1984 has a straightforward plot that interweaves two main stories, one focused on the scientific attempts to understand and contain Godzilla, and the other on the political ramifications of the monster’s unexpected rebirth. When Godzilla (played here with characteristic muscularity by Heisei-era suit actor Kenpachiro Satsuma) bursts out of a volcano, the Japanese authorities attempt, at first, to keep its re-emergence a secret, hoping that the creature will lay low and not cause any trouble. However, Godzilla soon forces their hand by destroying a Soviet submarine and almost provoking a catastrophic confrontation between the two nuclear superpowers. The uncovering of this secret quells the international tension, as it proves that no intentional provocation took place. Soon enough, however, Godzilla rampages through Tokyo, devastating the city and causing a Soviet nuclear missile to be remotely launched by accident. The Japanese Self-Defense Forces stop Godzilla with cadmium bombs and the US military launches a counter-missile, detonating the rogue warhead in the atmosphere above Tokyo. But the fallout from the blast reanimates Godzilla once again, and the only way to stop the beast is to lure it into another volcano using the insights gleaned from the scientific research of Professor Hayashida (Yosuke Natsuki). Falling back into the flames and lava of the underworld, Godzilla burns to death.

Godzilla 1984 is, then, the most direct engagement with Cold War themes to be found in the Godzilla series. Where the earlier films of the Shōwa period (1954-1975) addressed geopolitical matters playfully and obliquely through surreal symbolism and space opera allegory, Godzilla 1984 has explicit political themes front and center and throughout. Godzilla’s rebirth is the trigger event so widely dreaded in the 1980s: a sudden, destabilizing, and unpredictable crisis that threatens the delicate geopolitical balance and pushes the world closer to mutually assured destruction.

But though World War 3 may loom menacingly, Godzilla 1984 dispels the threat of nuclear war relatively quickly. The film’s concern is not the fear that an apocalyptic exchange of annihilations will take place between the nuclear powers, because, as mentioned above, the revelation of Godzilla’s responsibility for the destruction of the nuclear submarine quickly calms these fears. The specific and more nuanced fear that the film exploits is that a “slippery slope” effect could result from the use of nuclear weapons in this emergency. Times of crisis are, after all, times of temptation: when things get tough, the option to discard sensitive ethical principles and use brute force to solve problems seems ever more persuasive—as the Japanese were, of course, well aware, having been the victims of American nuclear aggression. Godzilla 1984 is that rare cultural artifact that doesn’t portray crisis as a time when an exception can be made. Instead, the movie foregrounds the struggle to stand by one’s principles when they are most sorely tested.

This concern is most pronounced in a scene roughly halfway through the film. American and Soviet negotiators attempt to persuade the Japanese Prime Minister Seiki Mitamura (Keiju Kobayashi) to allow the use of nuclear weapons against Godzilla on Japanese territory. Harangued on both sides, the Prime Minister eventually stands firm in his anti-nuclear convictions. Pacifist principles mean nothing, he says, if we abandon them when they become inconvenient. More than anything, then, the film is a reaffirmation of Japan’s anti-militarist credo, enshrined into their post-war constitution in the form of a commitment to never again wage war. Even using nuclear weapons “defensively” is rejected: any deployment at all will legitimize their use and thus set a precedent that will encourage, however indirectly, their use in the future. (Of course, nuclear weapons are used, as a US missile intercepts the rogue Soviet warhead; but this is a tragic eventuality, an outcome that shows that the only justified use of nuclear weapons is itself anti-nuclear.)

This long negotiation scene also articulates a clear and passionate commentary on the Japanese national position during the Cold War. When the Japanese Prime Minister, once he’s finished discussing matters with his cabinet, plainly refuses to allow nuclear weapons to be used against Godzilla, he finishes his remarks by asking by what right the USA or Russia can demand to use these weapons on Japanese soil. “You accuse us of acting out of national pride, and maybe we are guilty of that. But what of your attitude? What right do you have to say that we should follow you? You are being selfish too.” Like the much later Shin Godzilla (2016), which sees Japanese authorities collaborating with American and French forces in their attempts to destroy the monster, Godzilla 1984 shows a Japan that can assert itself as a nation among equals, refusing to be dictated to. There is a certain nationalism here, of course, but also a tentative anti-imperialism. Both the US and Soviet ambassadors are pushy, aggressive, overconfidently combative; the Japanese PM is calm, reserved, above all human, his hands trembling as he holds his cigarette in his office and explains to his ministers how he finally managed to resolve the situation. Unlike the representatives of the nuclear powers, who seem to feel they have finally found the opportunity they crave to push the nuclear button, the Japanese—the only nation to have actually been on the receiving end of a nuclear strike—have a uniquely intimate insight into the human costs of nuclear aggression. This insight demands that they exhibit the vigilance and courage to say no, always, to nuclear weapons.

Rebirth, Resurrection

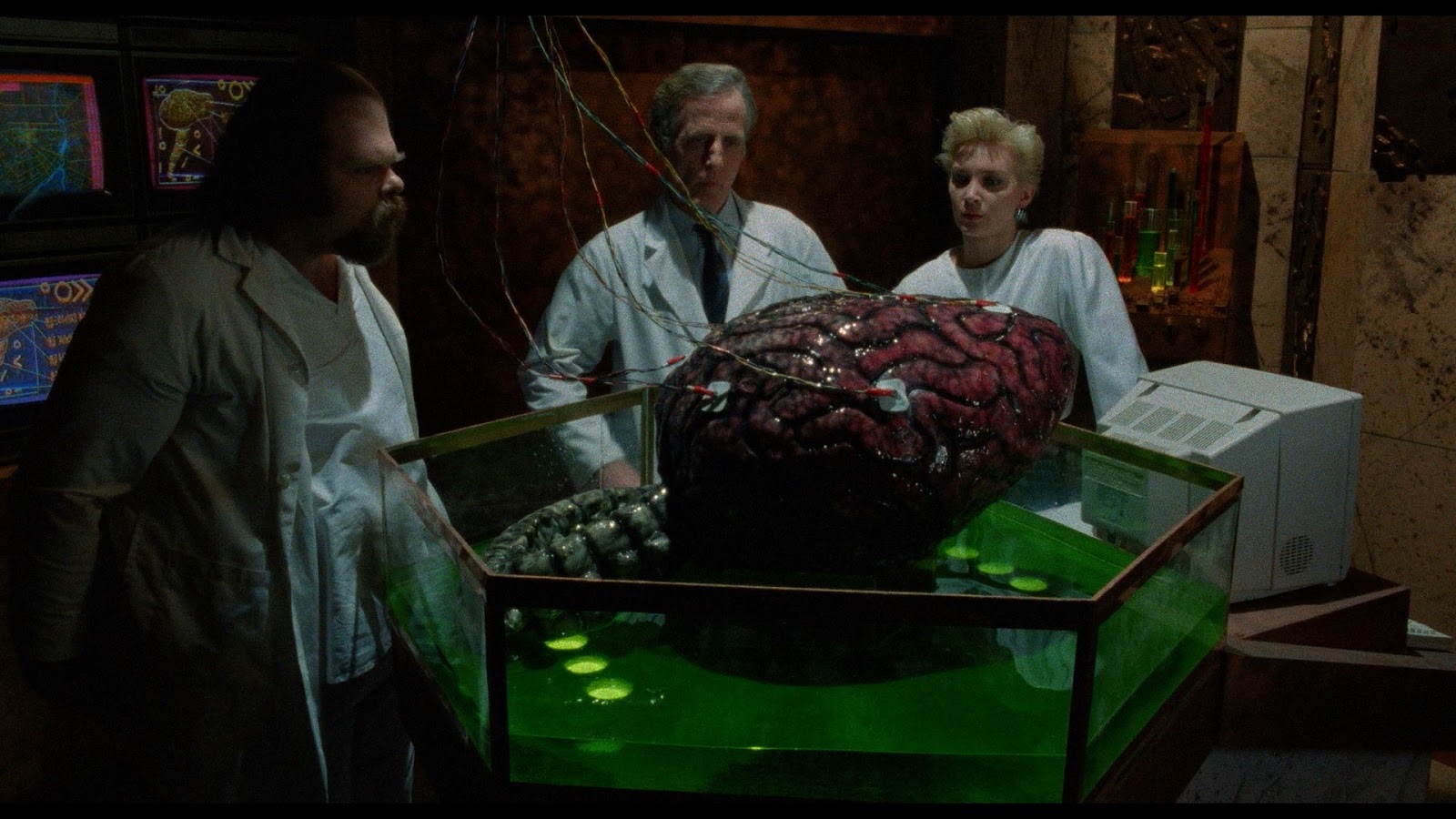

It’s not only the film’s more open approach to its political commitments that sets Godzilla 1984 apart from previous Godzilla movies. It also has grittier visuals and a more realist narrative approach, blending elements of the horror and political thriller genres into a more stylistically austere version of giant monster science fiction. The tone is darker, tragic, more serious; there are no more victory dances, special moves, speech bubbles, child protagonists, or plucky kaiju sidekicks. In place of these fun, carnivalesque elements that characterize many of Godzilla’s later Shōwa features, Godzilla 1984 prioritizes Godzilla annihilating Tokyo by night while the itchy trigger fingers of global superpowers threaten nuclear winter. The film’s opening has a pulpy horror feel, featuring spooky green lighting, grisly gloop and grue, and corpses sucked dry by a giant facehugger-esque sea-tick. Its closing movement is slow, quiet, elegiac, full of moments of aching stillness as the confused monster is led to its doom. Like only three other Godzilla films (the original, Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Godzilla, and Shin Godzilla), Godzilla does not fight another monster, allowing the primal majesty of the monster itself to take center stage.

This majesty feels a little understated, though, as Godzilla’s redesign is only partially successful. There is lots to love, particularly in the creature’s auditory profile. The crashes and booms of its stomping feet are satisfyingly cacophonous, and the roar is more animalistic, guttural, and thunderous—more, in short, like the roar found in the original Godzilla and less like the more jovial skreeonk heard throughout the comparatively light-hearted sequels of the 1960s and ’70s. On the other hand, the suit often looks goofy due to its clunky articulation and static, inexpressive eyes; and compared with Godzilla’s previous destructive antics, the rampage through Tokyo feels lukewarm and low-energy. But it is the characterization of Godzilla as what director Koji Hashimoto calls “a living conflict of evil and sadness” that ultimately makes the new Godzilla an effective beast. Though critics have dismissed Godzilla’s slow movement in this movie as aimless, dawdling, and boring, the monster seems more sympathetic, and more interesting, when interpreted as a confused, hapless, and hungry creature struggling to understand the world around it. Neither a conquering embodiment of sheer, malicious onslaught or a swashbuckling, child-friendly superhero, Godzilla appears here as a tragic, doomed figure, lost in a baffling and hostile environment. This iteration of Godzilla speaks to the confusion and helplessness felt by many in the face of the absurd yet terrifyingly real nuclear threat.

The deliberate strategy of positioning Godzilla 1984 as more grown-up, more aesthetically mature, is an attempt to refurbish Godzilla’s reputation, to wipe away the embarrassment of the increasingly goofy Shōwa years. Many fans (myself included) love the more freewheeling 1970s films, with their wackier stories and more outré characterizations—such as the space cockroaches using an amusement park to infiltrate human society in Godzilla Vs. Gigan (1972), the sentient robot Jet Jaguar who helps Godzilla destroy an avenging hollow earth cockroach in Godzilla Vs. Megalon (1973), and the dog-god King Caesar who helps destroy Godzilla’s metal doppelganger in Godzilla Vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). But Steve Ryfle, in his book Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star, speaks for many when he calls the post-Destroy All Monsters (1968) movies Godzilla’s “dark days” because of the dramatic drop in both seriousness and production value.

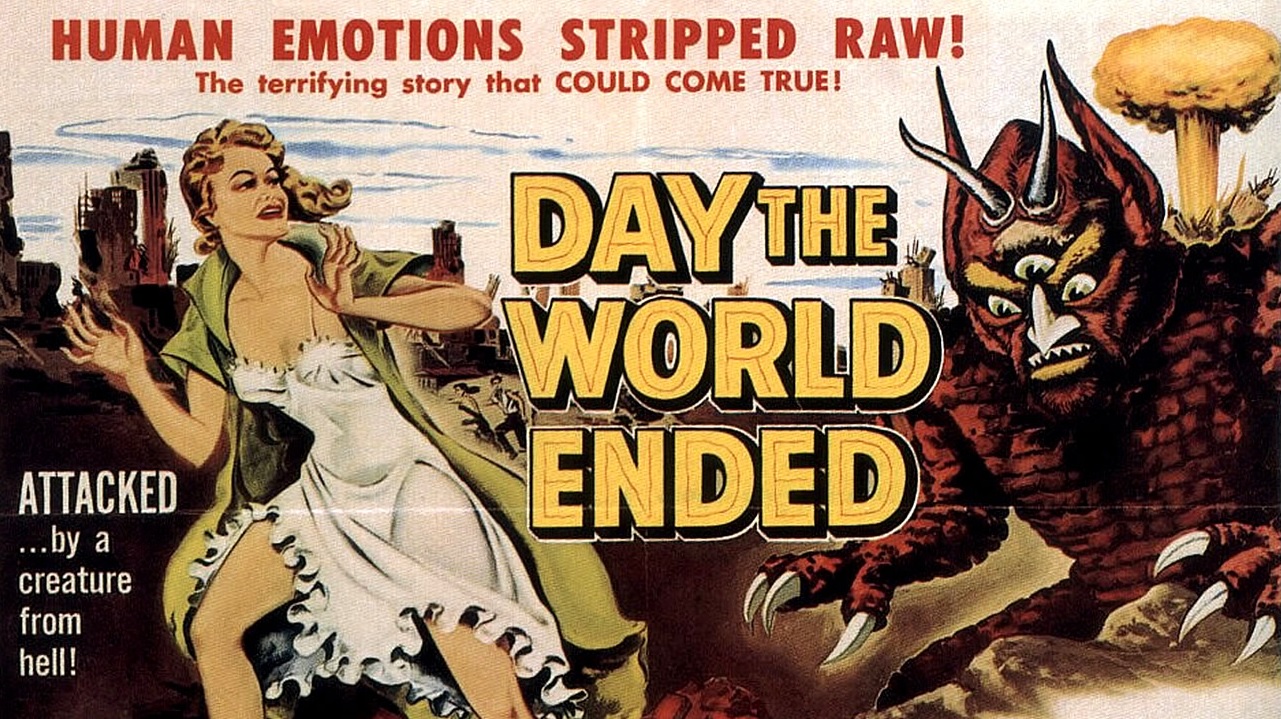

And it is true that these later stock footage-laden sequels were made on lower budgets, catered to a younger audience, and saw decreasing ticket sales. The rise of TV kept audiences away from the cinema, and genre competition from the likes of American import Star Wars, rival studio Daiei’s turtle kaiju Gamera, and TV sensation Ultraman dethroned Godzilla from his status as King of the Monsters, demoting him into a mid-field also-ran no longer able to dominate at the box office. This reduction in quality is reflected in the critical consensus around these later movies, which very often dismisses them as tacky pop culture crap that reflects poorly on the brooding arthouse gravitas of the 1954 original. “Americans in particular,” writes Den of Geek, “were coming to see Godzilla films as a punchline, as the cheapest of the cheap and the dumbest of the dumb.” The child-friendly animation series by Hanna-Barbera (1978-79), with its fairy-tale tone, grating levity, and the Scrappy Doo-esque mini-monster Godzooky, did nothing to counter this reputation.

These judgements about the cultural value of entertainment clearly influenced the creative process of Godzilla 1984. If this new incarnation was to be taken as seriously as its creators felt Godzilla deserved, the film needed to comprehensively parade its seriousness. It has its moments of humor and brightness, of course, but the movie’s color palette is dominated by blacks, grays, and reds; its soundtrack is an opulent mixture of the heavily percussive and the orchestrally mournful; and its conclusions (both narrative and philosophical) are somber. For some critics—notably the condescending Roger Ebert, who said in his error-filled one-star review that the movie deliberately echoed “the absurd dialogue, the bad lip-synching, the unbelievable special effects, the phony profundity” of the original—this was not a task worth taking time over. But for others, the return to darkness is a return to form, and the movie was successful enough to initiate a run of six increasingly flamboyant sequels. From 1989 to 1995, a new series of “versus films” would feature wild, bizarre plots worthy of the Shōwa era and a newly threatening, grimly charismatic Godzilla.

Your Favorite Fire-Breathing Monster… Like You’ve Never Seen Him Before!

Godzilla’s history is, to an extent at least, a history of cross-cultural communication. As Japan modernized rapidly in the decades after the Second World War, its popular cultural export business, including anime and manga (from the surreal darkness of Akira and Ghost in the Shell to the melancholy whimsy of Studio Ghibli), extreme horror movies by auteurs such as Takashi Miike (whose 1999 Audition and 2001 Ichi the Killer pushed the horror envelope at home and abroad), video gaming platforms and characters including Nintendo, PlayStation, and Pokemon, and popular toy lines such as Gundam Wing and Bandai’s two brands Transformers and Machine Robo (known in the West as Gobots), constituted one of the most important aspects of its economic recovery. Tokusatsu—special effects movies, including kaiju movies—were no small part of this outpouring of soft power.

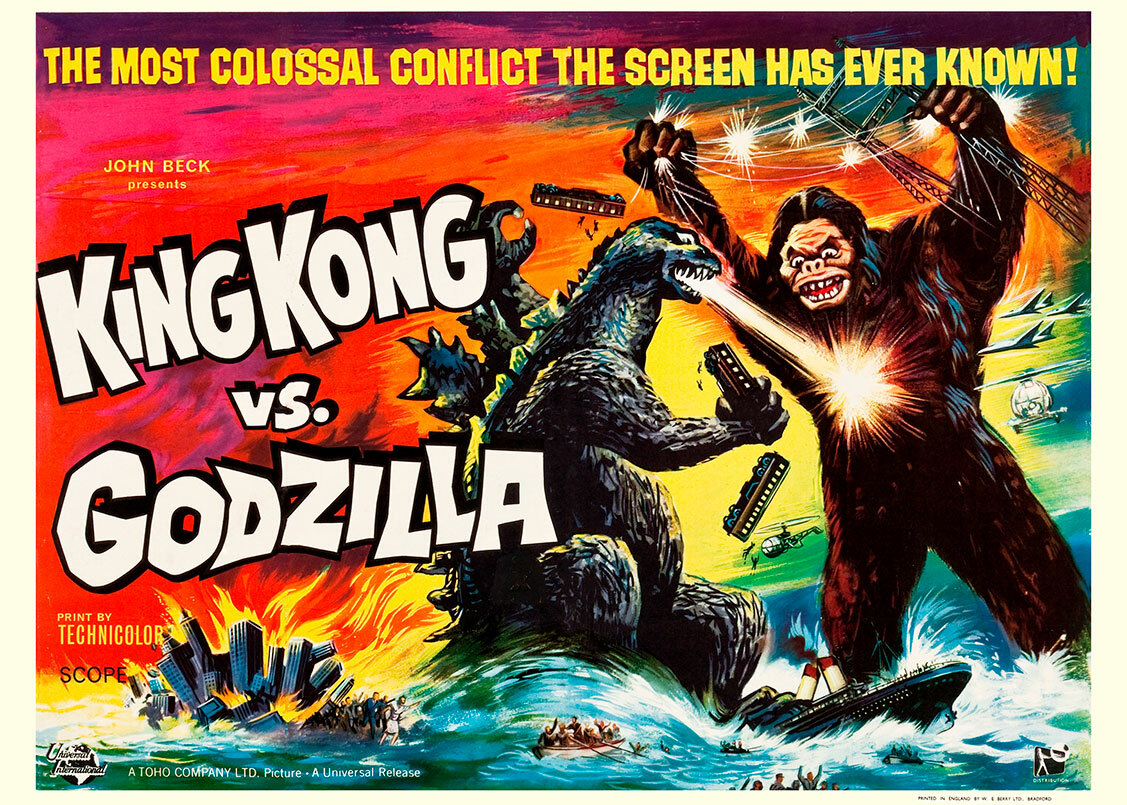

But Godzilla’s history in the West is also, in large part, a history of bowdlerization. Godzilla: King of the Monsters! (1956) was a tonally sympathetic adaptation of the 1954 original; it retained a great deal of the original performances and much of the best effects work, adding Steve Martin (Raymond Burr), an American journalist functioning as a focalizing character who narrated the plot more or less directly to the audience. For years, however, Toho’s poor grasp of overseas licensing meant that US distributors (keen to exploit the films financially, but utterly unsentimental about their content) were often free to butcher subsequent movies willy-nilly, adding stock footage, new music, and comically bad dubbing. Though the rationale for these editorial intrusions was usually that such changes were intended to make the films more accessible to non-Japanese audiences, some of the interventions seem brutal and ludicrous to later viewers, many of whom prefer to see the films as close to the way their original creators intended as possible. Godzilla’s first sequel, Godzilla Raids Again, was recut and retitled Gigantis! The Fire Monster (1959)—as well as stuffing it with stock footage and giving it a patronizing explanatory voice-over, the adaptors even changed Godzilla’s name—and sequel number two, King Kong Vs. Godzilla, had vital scenes of exposition, comedy, and characterization stripped out and replaced with a talking head newscaster who directly and listlessly explained the plot to the audience.

Compared with rough handling like this, Godzilla 1985 is a mostly thoughtful and considerate adaptation of Godzilla 1984. Much as the Japanese version is a blank slate reboot of the original Godzilla, the American recut is a direct sequel to Godzilla: King of the Monsters! And, like its predecessor, Godzilla 1985 features a light-touch streamlining of the narrative, a reasonably proficient dub, and the retention of much of the original score. That said, Godzilla 1985 has its share of problems. Reviews were generally poor, with critics often targeting the special effects, which seemed old-fashioned and underwhelming to US audiences now used to the visual wonders experienced in films like Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982), and The Terminator (1984). “Though special-effects experts in Japan and around the world have vastly improved their craft in the last 30 years,” wrote the New York Times, “you wouldn’t know it from this film.” Elsewhere, the adaptation process itself took flak. A redundant sub-plot featuring American military characters, which is shot on a visibly flimsy set and padded with silly jokes, was added. On this count, Steve Ryfle is particularly withering, noting that this narrative element makes Godzilla 1985 “a dead serious Japanese monster movie interrupted every ten minutes or so by pointless vignettes featuring (mostly bad) American actors, including a wisecracking military punk who should be shot.”

But this is the least of it. Godzilla 1985 is now notorious for its extraordinarily heavy-handed Dr Pepper product placement. Dr Pepper stumped up a proportion of the cash for the reshoots, and they demanded a lot in return. As a result, the American characters approvingly sip the beverage in the war room and converse in front of a dazzlingly bright vending machine. In the campy tie-in promo adverts, Godzilla attacks Tokyo in search of the soft drink, and his picky girlfriend Lady Godzilla demands the diet version. Though the tonal reset of Godzilla 1984 sought to distance Godzilla from the sillier aspects of the monster’s reputation, the studios responsible were clearly happy enough to exploit this reputation for marketing and promotional purposes.

Perhaps most importantly, however, Raymond Burr reprises his role as the journalist Steve Martin, appearing here as a world-weary father figure summoned by the US military for his insight into the original disaster. Legend has it that Burr had a profound influence on the project, rewriting or extemporizing lines, refusing to drink Dr Pepper, and forcing the production team to take the subject matter seriously. Whether or not these stories are apocryphal—a recent piece in fanzine Kaiju Ramen suggests that there is little evidence to actually support such tales—Burr definitely brings a certain hammy seriousness to the new scenes without which they would be much the poorer. Much as the Japanese Prime Minister is the voice of conscience in Godzilla 1984, in Godzilla 1985 Martin is a grizzled and wise elder who dampens the youthful enthusiasm of the American military officers with his cynical testimony from the past. Martin offers nuggets of expertise about Godzilla’s behavior, expertise gained from his exposure to the beast but also, it is implied, from years of thoughtful reflection on the matter. He is clear, for instance, that military force will yield no results. “Firepower of any kind or magnitude is not the answer,” he states. “Godzilla’s like a hurricane or a tidal wave. We must approach him as we would a force of nature. We must understand him, deal with him, perhaps even try to communicate with him.”

The movie closes with an ominous monolog delivered by Burr, which is rich in metaphysical claims about humanity’s inability to challenge the colossal natural forces that Godzilla represents:

Nature has a way sometimes of reminding man of just how small he is. She occasionally throws up the terrible offsprings of our pride and carelessness to remind us of how puny we really are in the face of a tornado, an earthquake, or a Godzilla. The reckless ambitions of man are often dwarfed by their dangerous consequences. For now, Godzilla, that strangely innocent and tragic monster, has gone to her. Whether he returns or not, or is never again seen by human eyes, the things he has taught us remain.

Godzilla 1985 is, then, much more didactic than Godzilla 1984, and by hammering the message home so hard it also loses a lot of its subtlety and sophistication. Much of the complexity of the negotiation scenes is stripped out, for example, replacing the debate among the Japanese cabinet with a straightforward refusal to countenance nuclear weapons. This retains the superficial anti-nuclear message of Godzilla 1984 but cuts out the discussion of Japan’s right to participate as an international equal, reducing the thorny discussion of Japan’s delicate geopolitical position to a flat and peremptory rejection of nuclear weapons. Removing these scenes and inserting far less interesting pontifications on man’s relationship with nature—“Godzilla’s a product of civilization. Men are the only real monsters,” says Professor Hayashida—may make the film more palatable to international audiences (although it’s not clear how we would know whether this is really true), but they do so at the cost of dampening and impoverishing the movie’s political insights. Godzilla 1984 gives us a glimpse into Japan’s Cold War position; Godzilla 1985 gives us pompous platitudes about the power of nature.

This distortion is found throughout other American adaptations of Godzilla. In Emmerich’s Godzilla, the monster is awoken by French nuclear testing in the Pacific, and Gareth Edwards’s Godzilla (2014) reframes US nuclear testing in the 1950s as attempts to kill Godzilla. Edwards’s film (as well as its sequel, 2019’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters) does feature Dr. Serizawa’s father’s stopped pocket watch, a family heirloom from Hiroshima, but in general there is a tendency in US adaptations to minimize American historical responsibility for the actual use of nuclear weapons against human targets. Godzilla 1985 is notable in this regard, as perhaps its most striking change is that the Russians are transformed into nuclear aggressors. Where the Russian officer tries desperately to stop the launch in Godzilla 1984, in Godzilla 1985 this scene is subtly recut to indicate that the Russian’s dying struggle is in fact motivated by his desire to ensure that the missile is launched. To the last breath, the Soviets are murderous villains.

This extraordinary political about-face, in which the movie is changed from a piece of anti-nuclear pacifism to a piece of Reaganite anti-Soviet propaganda, is explained, in part at least, by the conservative politics of the owners of New World Pictures. Originally started by B-movie legend Roger Corman, by 1985 New World was owned by execs Larry Kupin, Harry E. Sloan, and Larry A. Thompson, whose conservative affiliations led to the studio cutting out valuable scenes examining Japan’s right to refuse the demands of the two nuclear superpowers, as well as cynically turning the Soviets into villains. For many viewers this change is not only nonsensical and ridiculous but actively undermines the longstanding political commitments of the Godzilla franchise. Another reviewer writes that in Godzilla 1985 “the Russians take the place of all those goofy alien races that populated the 1960s and 70s-era Godzilla movies.” The Kilaaks and Xiliens were, I have written elsewhere, allegories for aggressive imperial powers; in this light, it is particularly disappointing that Godzilla 1985 makes this change. Where Toho’s previous films—and, indeed, Godzilla 1984—are critical of imperialism, Godzilla 1985 is a piece of imperial propaganda directly engaged in the Reaganite public relations project of demonizing Communism.

In the final analysis, however, Godzilla 1985 is perhaps more interesting than Godzilla 1984. Its distortions of the Japanese version throw light on what is most compelling about the original, and there is a lot of apocrypha to go around to boot. It is fun, for instance, to imagine the trepidation of the production staffer tasked with asking Raymond Burr to approvingly quaff Dr Pepper before delivering a line about man’s fragility in the face of the overwhelming mystery of nature. And home video sales of Godzilla 1985 were a major success, contributing massively to the continued overseas popularity of Godzilla. It is only a shame, then, that no official home video release of Godzilla 1985 exists, at least not here in the UK where I’m writing from. While Toho is putting out Godzilla hot sauce, Godzilla coffee, and Godzilla drinking chocolate, it remains the task of amateur preservationists to ensure that the films themselves remain in circulation.

Godzilla 1984 generated six sequels over the next eleven years, with a revamped Godzilla battling old foes King Ghidorah, Mothra, and Mechagodzilla, as well as new creatures Biollante, Spacegodzilla, and Destoroyah. These Heisei-era versus films represent the franchise’s first sustained attempt at the sort of inter-film continuity that modern audiences recognize and expect, with a consistent set of characters, later films following up on previous movies, and something of a long-term narrative arc. For me, this sequence of films also represents some of the highest points of the entire franchise, as they feature glittering and pyrotechnically adventurous practical effects at their most wondrous, monster design that is iconic and inventive, and some of the most interesting themes in the series, from the dystopian vision of bioweaponry and espionage in Godzilla Vs Biollante (1989), to the hopeful environmentalism of Godzilla Vs Mothra (1992), to the detonation-heavy antimilitarism of Godzilla Vs Mechagodzilla II (1993). The late Cold War oddity of Godzilla 1984, then, and its much-maligned recut Godzilla 1985, would be the catalyst for a resurgence in Toho’s tokusatsu fortunes that continued long after the tensions the movie took as its subject matter were permanently transformed. The world may change around the monster, but the monster itself is immortal.

Alex Adams is a cultural critic and writer based in North East England. His most recent book, How to Justify Torture, was published by Repeater Books in 2019. He loves dogs.

Alex Adams is a cultural critic and writer based in North East England. His most recent book, How to Justify Torture, was published by Repeater Books in 2019. He loves dogs.

![]() Ty Matejowsky is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. He is a Libra who enjoys sunsets and long walks on the beach.

Ty Matejowsky is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. He is a Libra who enjoys sunsets and long walks on the beach.