M.L. Schepps / August 6, 2020

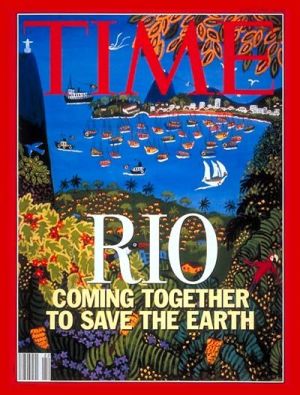

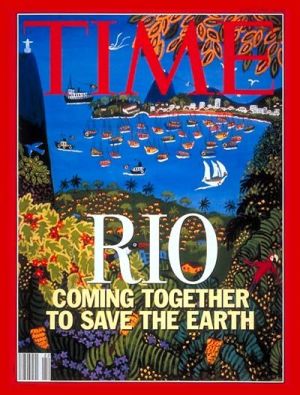

At the break of dawn upon the beach, a thousand representatives of the “Female Planet”—ranging from white-clad Canbomblé, damp in honor of the ocean goddess Yemoja, to realtors from Anchorage—raised mirrors to the pallid sky, seeking to reflect the light of their hope towards the sprawling Riocentro Convention Center that was the focus of the world’s attention. Amid a sense of urgency, representatives from 178 nations gathered for what was the largest United Nations conference in history. Activists, scientists, prominent entrepreneurs, entertainers, and world leaders alike urged unity and immediate action, while one representative of the youth environmental movement emphasized that “we’re all in this together.” The year was 1992, and the Earth Summit was underway in Rio de Janeiro.

At the break of dawn upon the beach, a thousand representatives of the “Female Planet”—ranging from white-clad Canbomblé, damp in honor of the ocean goddess Yemoja, to realtors from Anchorage—raised mirrors to the pallid sky, seeking to reflect the light of their hope towards the sprawling Riocentro Convention Center that was the focus of the world’s attention. Amid a sense of urgency, representatives from 178 nations gathered for what was the largest United Nations conference in history. Activists, scientists, prominent entrepreneurs, entertainers, and world leaders alike urged unity and immediate action, while one representative of the youth environmental movement emphasized that “we’re all in this together.” The year was 1992, and the Earth Summit was underway in Rio de Janeiro.

Over 40,000 delegates had flown in for this ambitious conference, which sought global cooperation in the face of rising pollution, global warming, and deforestation. Delegates and performers included the headlining Placido Domingo, the Dalai Lama, Shirley Maclaine, and a “who’s-who” of early ‘90s hotness, with River Phoenix, Jeremy Irons, and Edward James Olmos in attendance among what one British paparazzo referred to as “all the nutters in the world.” By the end of the conference, it was already considered a failure. President Bush’s refusal to sign on to the keynote agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, had drawn fiery attacks by the presumptive Democratic nominee, Bill Clinton, who asserted that Bush had “abdicated both national and international leadership” in environmentalism, making the United States the “lone holdout” in a world that recognized the urgency of action. In response, Bush defended his record, emphasizing that “environmental protection makes growth sustainable.”

The world hinged on a great axis. The Berlin Wall had fallen only months prior and capitalism stood astride the global stage, triumphant. The American way of life had won, and all that remained was saving the planet. Bill Clinton would go on to be the first baby boomer president, setting the stage for that cohort to at last live up to the world-changing aspirations of their adolescence. It was to be a new and transformative era, one in which the mandates of capitalist economic expansion might be constrained in the service of sustainability. The Secretary General of the conference, Maurice Strong, acknowledged that the road ahead would be a difficult one, but “it will also be a journey of renewed hope, of excitement, challenge and opportunity, leading as we move into the 21st century to the dawning of a new world.”

And it was a new world—but not at all the one the organizers anticipated. 1992 heralded a significant turning point in the mechanisms that define our society: the neoliberal consensus became inviolate and fully bipartisan, with devastating consequences for the environment. Neoliberalism is a word that is often used—and overused—without explanation. George Monbiot has pointed out certain ideological hallmarks that can be taken as representative of the term: the primacy of the individual over the collective; that individual action should be expressed through consumer choices and consumerism; the exaltation of capital and a free market protected by the rule of law but unfettered via regulation; and reduced taxation, increased austerity, and governmental assistance for corporations instead of individuals, coupled with a devotion to privatization of public goods and services.

And it was a new world—but not at all the one the organizers anticipated. 1992 heralded a significant turning point in the mechanisms that define our society: the neoliberal consensus became inviolate and fully bipartisan, with devastating consequences for the environment. Neoliberalism is a word that is often used—and overused—without explanation. George Monbiot has pointed out certain ideological hallmarks that can be taken as representative of the term: the primacy of the individual over the collective; that individual action should be expressed through consumer choices and consumerism; the exaltation of capital and a free market protected by the rule of law but unfettered via regulation; and reduced taxation, increased austerity, and governmental assistance for corporations instead of individuals, coupled with a devotion to privatization of public goods and services.

It is this ideology, shared by centrist Democrats and “mainstream” Republicans alike for at least the last 40 years, that is responsible for unmitigated inequality, looming environmental collapse, and “our” complete inability—or refusal—to stop any of it.

Despite these realities, my childhood recollection of the early ‘90s is one of hope and determination. “Everyone” knew and believed certain truths, it seemed: global warming was real and an imminent danger, the Amazon Rainforest was being destroyed, dolphins were bloodily decimated to produce tuna. The corollary to this knowledge was the bone-deep conviction that, yes, these problems were real—but they were being taken care of. The good guys (Democrats) were now in charge, and the bad guys (Republicans) were in the rear view. Things seemed set to be sustainably tubular, organically rad, and bodaciously green.

Two pop culture artifacts from the era reflect this sense of optimism: 1990’s Captain Planet and 1992’s FernGully: The Last Rainforest. Both are products of the same “boomer ascendant” zeitgeist as the Earth Summit, full of laudable messages aimed at raising environmental consciousness. And both address the fundamental flaw in mainstream environmental movements—the neoliberal rot embedded at the roots. Their approach to this overarching issue, however, varies dramatically.

***

Billionaire futurist Ted Turner had a simple belief. He was “the second smartest thing on the planet” behind only one entity: “cartoons, because they speak every language.” Possessed of messianic leanings, Turner’s desire to “save the world” fit in nicely with his desire to increase market share through the acquisition of cartoon conglomerate Hanna-Barbera.

Turner and his “chief environmental watchdog,” Barbara Pyle, were both involved in organizing the Rio Earth Summit, and both left feeling disappointed. They felt that the conference had achieved perhaps “ten percent” of its potential due to the compromises demanded by the United States in its pre-conference negotiations, with Pyle going on to say that the summit was more of a “jazz funeral… a wake.” In the run up to the Earth Summit, Turner and Pyle collaborated on a cartoon broadcast on Turner’s networks with a simple if wide-reaching aim: “to arm a generation with the knowledge to find more sustainable ways of living on the planet.” The successes and failures of that cartoon can be seen as a metonym for the successes and failures of the mainstream Western environmental movement operating within the liberal, or neoliberal, paradigm.

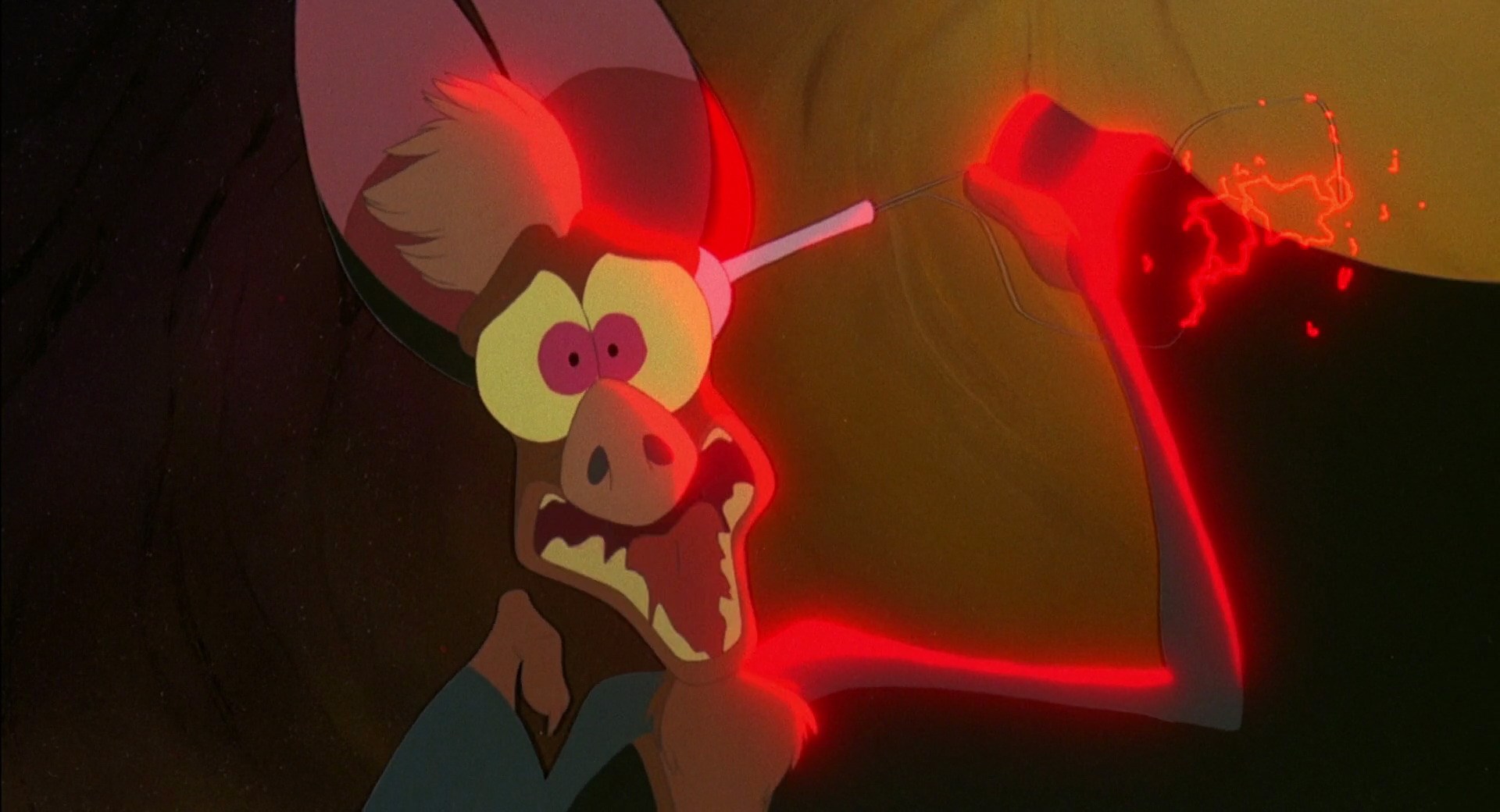

The first image of the first episode of Captain Planet and the Planeteers (1990-1992), “A Hero For Earth,” shows an idyllic, prelapsarian forest. Light shines upon a white rabbit hopping about, first in contentment, then in fear. The forest is being destroyed. Trees shatter, birds fall from their nests. A giant walking robot is the agent of this destruction. In the control room sits a grotesque, porcine figure in a pastiche of military uniforms. He snorts with glee and delivers exposition, in the curmudgeonly tone of Ed Asner: “Ha ha ha, with this giant land blaster I’ll be able to drill for oil anywhere!” His crony, Rigger, a wiry caricature of a “good ol’ boy” crossed with Salacious Crumb, responds affirmatively: “he he he, yeah boss, even in a wildlife sanctuary!”

The drill is extended from the walking machine. It penetrates the river below, thrusting through the water and into a glowing pink crack, smashing into a glass barrier. A single drop of liquid falls from the drill and lands on the face of a sleeping woman, draped in vaguely Medditeranean robes. She is awakened. She is Gaia, the living embodiment of the ecosphere.

This “subtext” is hardly sub. Captain Planet, the television show, begins with a rape—that of earth herself by the forces of industrialism. Gaia dismisses the invasion easily enough and repairs the fault, then remarks that she’s been asleep for a century and is now curious as to what those “silly humans” have been up to. We are treated to a flash of all the horrors of the 20th century’s environmental record.

Gaia decides that it is time to fight back. She summons adolescents from different regions of the world (with little more specificity for some beyond “Asia”) and includes a representative of the Soviet state. These are to be her soldiers: a diverse, multicultural coalition, speaking the international language (English with an accent), each one controlling a ring that corresponds to a different elemental control. The fifth team member from South America is given control over “heart.”

Gaia decides that it is time to fight back. She summons adolescents from different regions of the world (with little more specificity for some beyond “Asia”) and includes a representative of the Soviet state. These are to be her soldiers: a diverse, multicultural coalition, speaking the international language (English with an accent), each one controlling a ring that corresponds to a different elemental control. The fifth team member from South America is given control over “heart.”

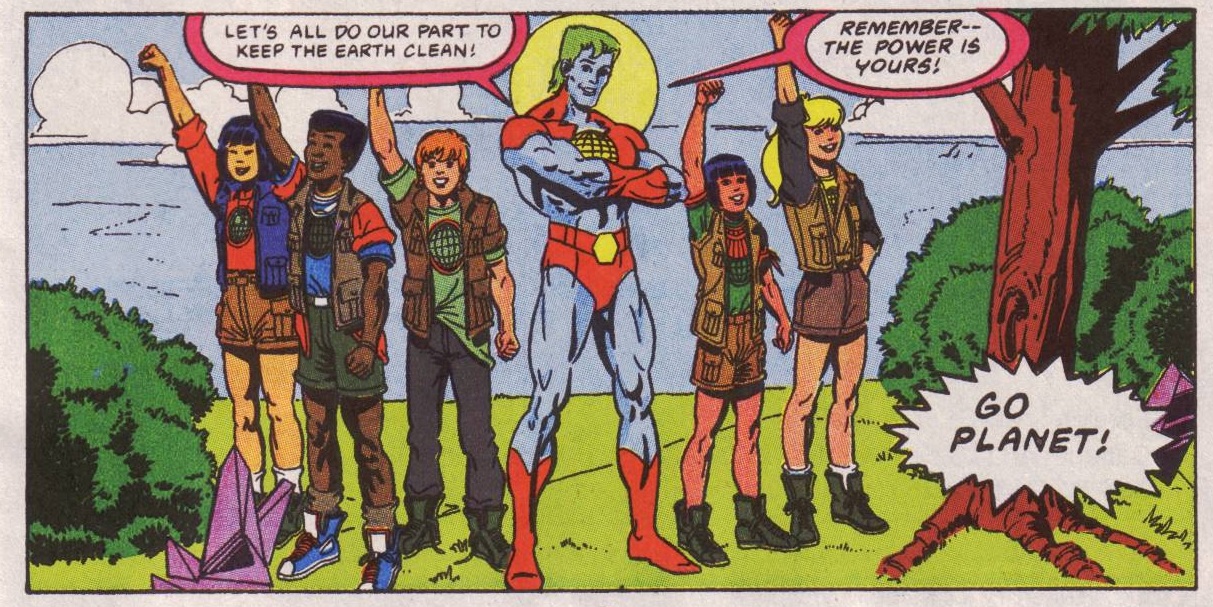

The Planeteers, teleported to Gaia’s base of “Hope Island” (the geography is very unclear), then fly north (in a carbon-emitting jet, despite Gaia’s proven ability to teleport) to confront the eco-villain. They are greeted by walruses covered in oil as the robot (now resembling an oil rig) drills. They fight the robot-drill but are forced to withdraw when the pigman threatens to spill his oil on the defenseless walrus. The team escalates, evoking the gestalt effect. By giving up their individual powers they can summon a greater warrior: Captain Planet himself, a mulleted superhero, the white, male, American leader of a diverse multicultural coalition. Again, the subtext is skin deep.

Captain Planet defeats the villains. Greedley escapes, though, and Rigger is given the equivalent of a slap on the wrist (dumped head first into a trash can) for abetting the destruction of a pristine ecosystem. In terms of semiotics, Greedley is the military-industrial complex and escapes any form of consequence; Rigger, just a “good-ol-boy” in search of a job, suffers no real punishment beyond temporary humiliation.

This first episode encapsulates the plot of essentially every episode: an “eco-villain” breaks the rules of conscientious capitalism and is confronted by the Planeteers, but ultimately defeats or traps them, after which they summon Captain Planet who, in turn, defeats the initial villain. The group then teaches the viewer, in an explicitly pedagogical segment, the ways they can help “save the planet.”

It is in this call to action (“the power is yours!”) that the fundamental flaws in the neoliberal approach to activism are most apparent. The Planeteers urge nothing but individual choices: encourage your family to drive less, carpool if you can, turn off the lights when you leave the room. In short: the problems are real but they are caused by consumer choices instead of systemic dysfunction, economic expansion, and unenforced regulation. It is this diffusion of responsibility that has proven a boon again and again to the system itself.

It is in this call to action (“the power is yours!”) that the fundamental flaws in the neoliberal approach to activism are most apparent. The Planeteers urge nothing but individual choices: encourage your family to drive less, carpool if you can, turn off the lights when you leave the room. In short: the problems are real but they are caused by consumer choices instead of systemic dysfunction, economic expansion, and unenforced regulation. It is this diffusion of responsibility that has proven a boon again and again to the system itself.

The effectiveness of this strategy is powerful. It can be seen in the way that disposable plastics manufacturers and soda companies devised the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign, absolving themselves of blame while shaming consumers for litter. It’s how 20 fossil fuel companies that have produced 35% of all carbon dioxide and methane released by human activities since 1965 have managed to get away with it.

Diffusion of responsibility is the voice that whispers, “Ah, the oceans are drowning in plastic? Should’ve recycled! Global warming threatens the vast majority of life in the biosphere? Well, it’s on you—should’ve carpooled!” It is the voice of the Planeteers when they tell us that “the power is yours,” but, crucially, not “ours.” There is no place for collective action in this conception of the world. The capitalist system itself is never questioned. The only role for the Planeteers is that of enforcing the “rules” of that system (“yeah boss, even in a wildlife sanctuary!”) and punishing the “eco-villains” (not Exxon or Dow, of course, but purposely exaggerated pigmen) that cause trouble. As a force, the Planeteers are reactive in response to pollution, never proactive in addressing the systems that cause and encourage these behaviors.

***

FernGully was released in 1992, the same year as the Earth Summit, and, much like Captain Planet, sought to instill a message of environmentalism to its viewership. Unlike Captain Planet, however, FernGully directly addresses the systemic issues responsible for unsustainability and places the blame fully on human agency and ideology.

In revisiting the movie, I was surprised by its maturity. I recalled a simplistic fable in which “fairies fight a pollution-monster with Robin Williams as comic relief.” The reality was far more complex and adult. The fairies are disconcertingly sexualized, with the protagonist Crysta seemingly modeled after a “Dancing in the Dark”-era Courtney Cox, her curves accentuated by crop-top and thigh-slit dress. Her romantic interest Zak is a bronzed-blonde, big-sneakered, mulleted-hunk with a Walkman and baggy jeans. They are both, as described later in the film, “Bodacious Babes.”

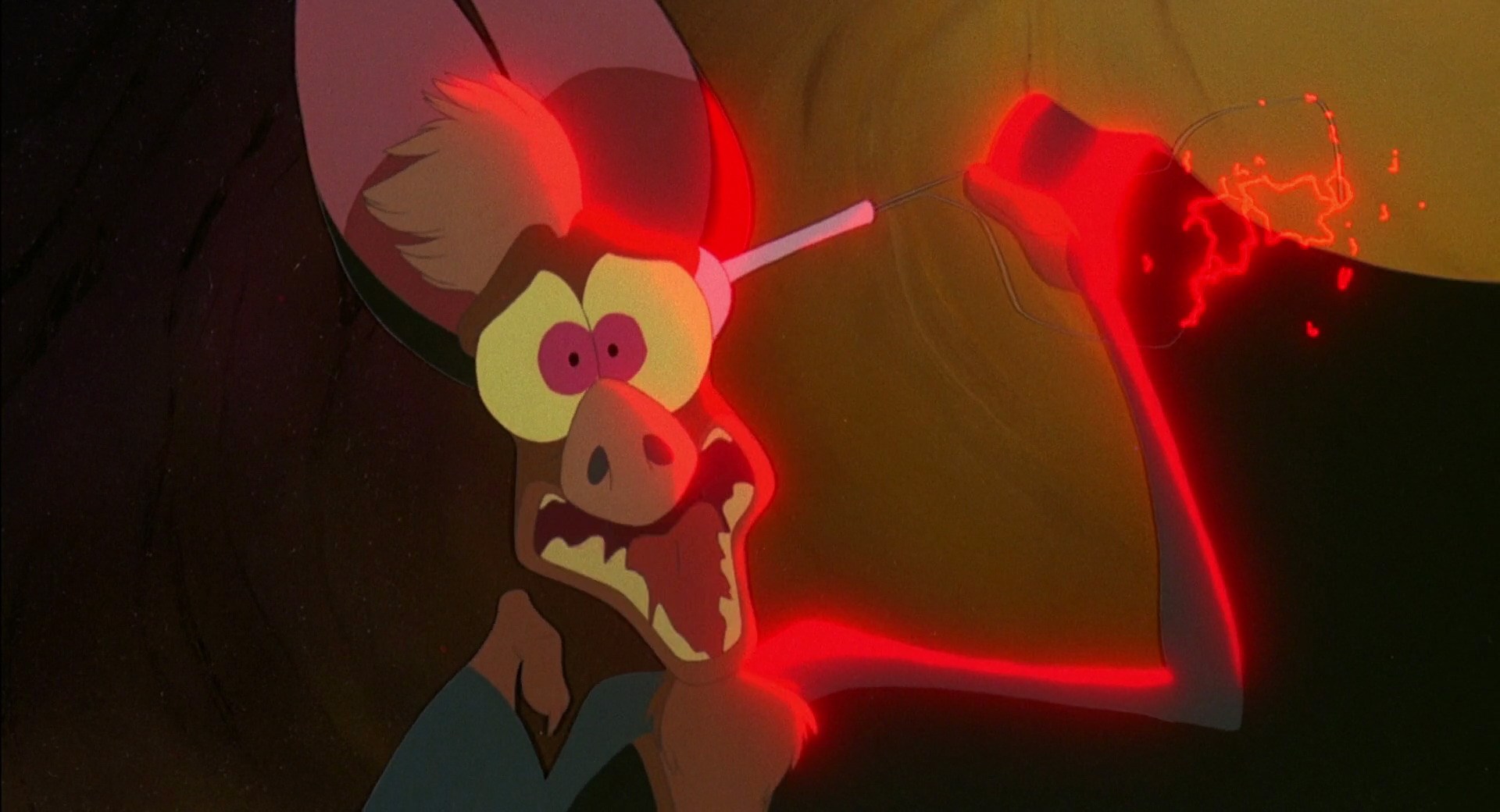

The part of the film I remembered most was Robin Williams’s Batty Koda. I recalled a character that was, much like Aladdin’s Genie, just an extension of his persona: a font of manic riffing and out-of-place impressions. Those aspects are there, of course, but the predominant trait of the character is the severe debilitation of trauma in the wake of torture at the hands of humans. Every aspect of the character is a testament to the fundamental evil of humanity’s relationship with nature. Batty (a bat) is a mauled escapee from a biology lab, the loose wires jammed into his brain depicted with pathos and visceral body horror. He suffers periodic seizures and dissociative episodes as a result of post-traumatic stress. He relates a trauma-rap (with that indelible early-’90s tone) wherein he describes being “brain-fried, electrified, infected and injectified, vivosectified and fed pesticides.” It is humor of the darkest kind, and the movie does not shy from it.

The part of the film I remembered most was Robin Williams’s Batty Koda. I recalled a character that was, much like Aladdin’s Genie, just an extension of his persona: a font of manic riffing and out-of-place impressions. Those aspects are there, of course, but the predominant trait of the character is the severe debilitation of trauma in the wake of torture at the hands of humans. Every aspect of the character is a testament to the fundamental evil of humanity’s relationship with nature. Batty (a bat) is a mauled escapee from a biology lab, the loose wires jammed into his brain depicted with pathos and visceral body horror. He suffers periodic seizures and dissociative episodes as a result of post-traumatic stress. He relates a trauma-rap (with that indelible early-’90s tone) wherein he describes being “brain-fried, electrified, infected and injectified, vivosectified and fed pesticides.” It is humor of the darkest kind, and the movie does not shy from it.

In short, this was not the trite, childish eco-fantasy I’d remembered, but rather one aimed at the kind of audience that might appreciate Tone Loc playing a hungry lizard and Cheech and Chong appearing as beetle-wranglers. This film was intended for a far wider and more discerning audience than Captain Planet and was the product of an independent animation studio adapting an original story with blatant environmental themes. Australian producer Wayne Young, enriched by the enormous success of 1986’s Crocodile Dundee, spent 15 years adapting the earnest environmental novel, which was written by his former wife Diane. The big-name stars of the movie worked for scale, forgoing significant payment due to the environmentalist message of what Young described in a 1992 issue of the Montreal Gazette as “a classically simple story… It won’t bend anyone’s brain to figure out what it’s all about.”

The plot of the film concerns a fairy society living in the lush Gondwana Rainforest near Mount Warning, part of what is today Wollumbin National Park in Australia. The fairies are tree guardians living in harmony with the natural world, and most have never seen a human. The movie begins with exposition from the leader, Magi, as she relates a story of long ago, when a primal force of destruction named Hexxus helped sever the harmonious bond between the tree fairies and the Aboriginal peoples of the region following a volcanic eruption. It is here that Hexxus’s identification with exploitative Western modes of thought is most apparent, his presence serving to separate the Indigenous Australians from FernGully itself. Hexxus was subsequently trapped in a tree and fairy society continued.

Crysta, her ‘90s bangs immaculate, is the protege of Magi and chafes under the restrictions of her society. One day she violates taboo by flying above the treeline. She sees a much wider world than she’d ever imagined, a vision of unending green marred by a plume of smoke in the distance. She then meets the aforementioned Batty, who seeks to warn the fairies of the horrors of encroaching humanity, his very body a testament; but, like Cassandra of Troy, he is unable to convince them of the impending threat. Batty’s presence as a victim of humanity is explicit and serves as an indictment of the original sin of Western environmental thought: humankind’s violent dominion over nature.

Crysta sets out to see the plume for herself, traveling through a defiled landscape to a logging site. She passes severed trees, their stumps marked with a bleed of red paint. The viewer is then introduced to mankind in the form of “the leveler,” a piece of forestry equipment based on a leveling track harvester but depicted as a horrific, smoking robot. It is this harvester that is most clearly coded as an abhorrence. The operators, Tony and Ralph, are depicted as bumbling slobs—but they are not evil. The machine itself—gleaming, fuming, jagged technology—is the force of evil. The act of technologically abetted forestry is explicitly identified as wrong.

Crysta sets out to see the plume for herself, traveling through a defiled landscape to a logging site. She passes severed trees, their stumps marked with a bleed of red paint. The viewer is then introduced to mankind in the form of “the leveler,” a piece of forestry equipment based on a leveling track harvester but depicted as a horrific, smoking robot. It is this harvester that is most clearly coded as an abhorrence. The operators, Tony and Ralph, are depicted as bumbling slobs—but they are not evil. The machine itself—gleaming, fuming, jagged technology—is the force of evil. The act of technologically abetted forestry is explicitly identified as wrong.

Crysta sees Zak Young, a young forester, and rescues him from a falling tree, accidentally shrinking him to fairy-size in the process. The two return to FernGully, where Zak at first hides his responsibility for the encroaching deforestation and generally just bros out with the fae, introducing them to cassette tape jams and accompanying Crysta to a narrow aquatic cave for a moist make-out that fades to black.

The leveler, meanwhile, cuts down and processes the tree imprisoning Hexxus, freeing him. Hexxus manifests as sludge (voiced by Tim Curry) and is delighted by the “clever, helpful” humans and the technology they’ve developed, expressing his belief that they’re “destined to be soulmates” with a bump-n-grind burlesque extolling the pleasure of “Toxic Love.” It is his intention to use “the machine they have provided” to convert the natural environment into capital, visualized as animals and trees turning into coins and bills. He then exercises his sole agency throughout the entire movie: impersonating Tony and Ralph’s boss through the radio and directing them to head to FernGully. The mechanism for their coercion is clear, as they are both excited at the prospect of “beaucoup overtime.”

This is a rich scene and one very much at odds with Captain Planet’s depiction of a well-regulated system subject to the malice of rule-breaking “Eco-villains.” It is capitalist consumerism—neoliberalism itself—that is the “machine they have provided” for the spirit of destruction. Hexxus revels in the machine, but it is not his: it is a human invention. Hexxus is clearly identified as the nameless, faceless voice of capitalism, the invisible engine powering the machine. He does not destroy, however—he provides economic incentives and lets the system work for him.

Back at FernGully, the disruption to the ecosystem is apparent in the poisoned rivers and dying vegetation. Crysta investigates and sees a vast clear-cut above the treeline. When she questions Magi as to whether or not it can be healed, Magi responds that she cannot because “a force outside of nature” is responsible, further identifying humanity as aberrant. Zak confesses, acknowledging that “humans did it. Humans did it all.” Zak informs them that their threat is a machine, defined as a “thing for cutting down trees.”

Back at FernGully, the disruption to the ecosystem is apparent in the poisoned rivers and dying vegetation. Crysta investigates and sees a vast clear-cut above the treeline. When she questions Magi as to whether or not it can be healed, Magi responds that she cannot because “a force outside of nature” is responsible, further identifying humanity as aberrant. Zak confesses, acknowledging that “humans did it. Humans did it all.” Zak informs them that their threat is a machine, defined as a “thing for cutting down trees.”

The fairies seem to accept their inevitable defeat and appear to retreat to a sacred tree, with Magi sacrificing herself to provide Crysta with a magic seed. The leveler, ridden by a laughing Hexxus, approaches the tree at the sacred heart of FernGully, its saws whirring implacably. Zak attempts to confront the leveler but is knocked to the ground.

Batty rescues Zak and tries to flee. Zak repays the rescue by physically manipulating the wires inserted in Batty’s brain, inducing a rapid-fire set of dissociative episodes that play out as Robin William’s comic impersonations set to a cocaine cadence. Batty is coerced into confronting the leveler when Zak triggers a “John Wayne”-type personality that charges the machine. Zak is thrown from Batty and lands on the windshield of the leveler, attempting to warn Tony and Ralph of his presence. They dismiss the warning until they see the actual physical manifestation of Hexxus and flee the cab, allowing Zak to enter and turn the machine off.

Hexxus is instantly diminished by the machine’s shutdown, wondering “what happened to the energy?” After a moment of audience relief, Hexxus rallies, now embodied as the fire from the burning fuel tank, growing as it prepares to consume FernGully after all. Crysta sacrifices herself by flying within Hexxus’s gaping maw, holding the seed. This is enough of a signal for the rest of the fairies to take collective action and “help it grow,” because “we all have a power and it grows when it shares.” This act sparks the regenerative power of nature to again bind Hexxus within a tree. Crysta is then reborn within a petal blossoming atop the tree.

Hexxus is instantly diminished by the machine’s shutdown, wondering “what happened to the energy?” After a moment of audience relief, Hexxus rallies, now embodied as the fire from the burning fuel tank, growing as it prepares to consume FernGully after all. Crysta sacrifices herself by flying within Hexxus’s gaping maw, holding the seed. This is enough of a signal for the rest of the fairies to take collective action and “help it grow,” because “we all have a power and it grows when it shares.” This act sparks the regenerative power of nature to again bind Hexxus within a tree. Crysta is then reborn within a petal blossoming atop the tree.

Crysta is reunited with Zak, rapturous that “Hexxus can never harm FernGully again.” Zak disabuses her of that notion by countering that Hexxus might not, but “humans still could,” explaining that he must return to human society to protect FernGully from further encroachment. He is returned to human size and finds Tony and Ralph, telling them “things have gotta change.” The forest, aided by the fairies, regenerates as a farewell gesture, and the movie ends with a dedication: “for our children and our children’s children.”

FernGully’s depiction of humanity as an inherently malevolent force in thrall to consumerism is a powerful one, but it was not all that far-reaching. The movie itself barely made back its budget, either because of its overt environmental messaging or simply because it wasn’t Disney. Its $32 million box office gross was about six-percent of Robin Williams’s other animated release that year, Aladdin.

Unlike Captain Planet’s individualist-consumerist approach to environmentalism, FernGully depicts a world where trees and the ecosphere have fundamental rights, and where real change is possible only through collective action and sacrifice. The “machine” can be stopped, but not permanently, not as long as the system that built it and set it loose remains in place.

***

When surveying the wreckage of the natural world and the inevitability of devastating climate change, deep ecological grief (or solastalgia) is a reasonable response. But there must also be anger over the possibilities that were stolen from us by the neoliberal consensus. Nearly everything we know today about the effects of pollution and the reality of climate change was known in 1992. The past thirty years have been a concerted effort by the forces of capital to engage in predatory delay: ensuring that the longer we wait to make changes, the more disruptive and difficult (and unlikely) they’ll be. The distinction between the left and the right on this topic is meaningless; it’s one where an ostensibly progressive president can oversee a vast increase in American gas production through the environmentally devastating use of hydraulic fracturing and still be considered “green.”

Things could have been very different after the Earth Summit. The reforms we might have made would have been relatively painless compared to the societal transformation that is now imperative if earth is to remain habitable. The world of “might have been” and “if only” is a painful one to revisit. Now, in a time shaped by the nihilism of the international right, the future of environmental collapse feels imminent. Decades of carefully calibrated and incremental environmental “progress” have been gleefully jettisoned by Republican revanche with no greater justification needed beyond destroying the biosphere to own the libs. In the face of this catastrophic intransigence, the conscious consumer can do little more than swear off plastic straws.

Duncan Macpherson/Toronto Star, 1992

Barbara Pyle saw the failures of the Rio Summit in real time, and was correct in predicting the influence of Captain Planet upon a generation. Millennials, staring down the barrel of our second economic collapse, recognize the urgency of immediate action. It is a recognition that is, unfortunately, worthless in the face of the gerontocratic stewards of the Democratic Party. We have been told all our lives that our prime civic contribution is to vote, that through “our powers combined” we might channel a force that is truly bigger than all of us. This generational yearning, growing increasingly urgent as time narrows, is constrained by the limits of what is possible in a neoliberal democracy. The current so-called “progressive voices” of our desperation are the same millionaire centrist old guard (Pelosi, Biden, Schumer, Feinstein, et al.) that have been in power all throughout the unraveling of our hopes—and our biosphere.

As the inherent tensions of America’s rapidly decaying society are exposed via a pandemic response that emphasizes individual choices at the expense of public health—fueled by the environmental consequences of now-irreversible global warming—the limits of individual, consumer-oriented activism are laid bare. Attempts to reform the system from within through electoralism remain stymied by the hard limits of the system itself. There are no superheroes or tree-fairies that we can call upon to deliver us from impending disaster.

This does not have to be the prelude to despair, however. Civil disobedience through collective action (as separate from the feel-good parades that characterize a great deal of public protest in the United States) remains the prime lever by which grassroots societal change is achieved. Over the past several years both Extinction Rebellion and the Black Lives Matter movement have engaged in collective action that emphasizes disruption outside of the inherently constrained limits of “peaceful protest.” We are also seeing an activist movement to remove the entrenched politicians on the “left” that have sleep-walked through the destruction of the biosphere; more diverse and progressive voices like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Jamaal Bowman have won primary victories and reflect a very real demand for immediate action and change. Proposed programs like the Green New Deal have the potential to mitigate the ongoing crisis of environmental and ecological collapse while also being broadly popular with a majority of the American public. However, elected progressives remain a small portion of the whole, and have the full force of capital, inertia, and predatory delay arrayed against them.

When the once hopelessly hopeful millennial, now approaching forty, surveys the ruins of the moment via the lens of their childhood pop culture, the gulf between the world we were promised and the world we now inhabit is dizzying. The challenges are overwhelming. We were raised to succeed in a society that no longer exists and—quite possibly—never did. But there are lessons to be found in the fables and allegories that shaped our worldview. We are not powerless. Widespread social change is possible, but it requires collective effort on a mass scale. The power was never “yours.” The power is ours.

M.L. Schepps lives in federally occupied Portland, where he takes many photos of birds. He spent the last year developing a deep appreciation of Kate Bush while also writing a book about 19th century Chinese immigration and Arctic exploration. Find more of his work at MLSchepps.com.

M.L. Schepps lives in federally occupied Portland, where he takes many photos of birds. He spent the last year developing a deep appreciation of Kate Bush while also writing a book about 19th century Chinese immigration and Arctic exploration. Find more of his work at MLSchepps.com.

Tom Brokaw popularized the term “The Greatest Generation” in 1998 to describe the Americans—and especially the American men—who survived the Depression and fought against Nazism in World War II. Brokaw saw this cohort in valedictory, heroic terms.

Tom Brokaw popularized the term “The Greatest Generation” in 1998 to describe the Americans—and especially the American men—who survived the Depression and fought against Nazism in World War II. Brokaw saw this cohort in valedictory, heroic terms.![]() Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

The Ecotopians are much more cagey about whether their society is “socialist” or not; certainly, the seizure of corporate capital in the first months of the Ecotopian revolution qualifies as classically socialist (“the forced consolidation of the basic retail network constituted by Sears, Penneys, Safeway, and a few other chains,” Weston notes), but Ecotopia is more properly classified as a mixed economy, as a private market and currency backed by a central bank does still exist. But it’s clear that at its base, Ecotopia is an essentially syndicalist-socialist state, with self-determination regarding labor being its organizing principle. Small groups of people numbering in the few dozens spontaneously form communes, farms, factories, educational foundations, and research facilities based on their common interests and goals. In addition, work assignments change depending on need and demand; students spend more time in university trying out different occupations, and every Ecotopian inevitably ends up owing service to their society outside their own job. The nuclear family has been largely upended by the Ecotopian revolution, with Ecotopian children raised by their “village.” On the larger scale, Ecotopian living communities are smaller and more self-contained. Along with the nuclear family, the commuter suburb has been destroyed in favor of self-sufficient “ring towns” surrounding larger urban conurbations, all linked by low-pollution high-speed trains. These basic changes in living structures have, within a generation, altered the Ecotopian psyche deeply. There is a greater openness to experience and to emotion, a greater sense of the interconnectedness of all Ecotopians.

The Ecotopians are much more cagey about whether their society is “socialist” or not; certainly, the seizure of corporate capital in the first months of the Ecotopian revolution qualifies as classically socialist (“the forced consolidation of the basic retail network constituted by Sears, Penneys, Safeway, and a few other chains,” Weston notes), but Ecotopia is more properly classified as a mixed economy, as a private market and currency backed by a central bank does still exist. But it’s clear that at its base, Ecotopia is an essentially syndicalist-socialist state, with self-determination regarding labor being its organizing principle. Small groups of people numbering in the few dozens spontaneously form communes, farms, factories, educational foundations, and research facilities based on their common interests and goals. In addition, work assignments change depending on need and demand; students spend more time in university trying out different occupations, and every Ecotopian inevitably ends up owing service to their society outside their own job. The nuclear family has been largely upended by the Ecotopian revolution, with Ecotopian children raised by their “village.” On the larger scale, Ecotopian living communities are smaller and more self-contained. Along with the nuclear family, the commuter suburb has been destroyed in favor of self-sufficient “ring towns” surrounding larger urban conurbations, all linked by low-pollution high-speed trains. These basic changes in living structures have, within a generation, altered the Ecotopian psyche deeply. There is a greater openness to experience and to emotion, a greater sense of the interconnectedness of all Ecotopians.

Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop

Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop