Joe Banks / December 23, 2020

Hawkwind live in 1973. Photo from the Japanese single for “Urban Guerilla”

Hawkwind are an indelible part of the UK’s underground culture. It’s been over 50 years since they formed in the seedy cradle of London’s Ladbroke Grove, but they still enjoy a fanatical cult following both in Britain and around the world. They may never have scaled the commercial heights of Pink Floyd or Led Zeppelin, but the influence they’ve exerted on modern music is profound. You can break down the components of their sound—barbarian psychedelia, propulsive rhythms, raw electronics—but what’s far harder to quantify is Hawkwind’s distinctive persona, their essential otherness within the story of rock.

In many ways, they’re a sub-genre to themselves, the house band of the British counterculture during the 1970s and beyond. There’s a parallel often made with the Grateful Dead in the US, and certainly from that period they share a similar sense of communal self-sufficiency (plus a propensity for extended jamming, though of a very different stripe to the blues ragas of Jerry Garcia’s crew). But whereas the Dead evoked a mystic vision of Americana, Hawkwind channelled the apocalyptic spirit of the age, fuelled by a combination of Cold War paranoia and pulp science fiction.

Along with the fearsome, if sometimes surprisingly complex, noise they made, it’s the SF-derived image and mythology that built up around Hawkwind that makes them truly unique in the annals of popular music, and that’s what I’m going to talk about in this article. My book Days Of The Underground – Radical Escapism In The Age Of Paranoia is an analysis of the band’s music and cultural impact during their “classic years” of the 1970s, and it looks at some depth into their sci-fi connections—but Hawkwind were still a potent force and SF nexus point in the early ‘80s, which was when I first seriously began to get into them.

Actually, I’d already had a head start; my older brother had a copy of their 1975 album Warrior On The Edge Of Time, which I would hear blasting out of his bedroom—its crashing riffs, rampaging Mellotron, and thunderous drumming loudly announcing a band that seemed to exist outside of the ‘70s rock continuum of Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, and Queen. But there were two features in particular that both fascinated and slightly unnerved my pre-teen self. Warrior’s sleeve depicted a silhouetted knight on horseback dwarfed by a garishly colored vision of the edge of time, with a mirror image of the same scene (minus the knight) on the back cover. The sleeve folded out and down to reveal a plunging panorama of the abyss below—but flip it over, and an impressive Shield of Chaos is revealed, giving a clue to the presence of a special guest within…

However, if the unusual sleeve created a frisson, the album’s spoken word interludes positively freaked me out. The bleak, pulsating chill of “Standing At The Edge” evokes a purgatorial nether zone of lost souls condemned to live forever, a voice full of petulant affront declaiming, “We’re tired of making love.” It’s like the final nail in the coffin of the hippie dream, calling time on the long ‘60s as the cold grip of the ‘70s takes hold. Elsewhere, the gentleman delivering “The Wizard Blew His Horn” and “Warriors” sounds alternately in the grip of mild hysteria and robotic possession.

Taking a closer look at the credits a few years later, I discovered that the voice behind those last two pieces belonged to none other than Michael Moorcock, whose Eternal Champion books the album is very roughly based around. Moorcock had first drifted into Hawkwind’s orbit in 1971, being also based in Ladbroke Grove. From here, he edited and published New Worlds magazine, the key journal of the so-called science fiction New Wave, as epitomized by the writings of J.G. Ballard. Moorcock could often be found of a weekend manning a second-hand book stall in the local market (as part of the constant effort to keep New Worlds afloat) or helping to organize open-air gigs under the Westway, the concrete overpass that looms above the area. Hawkwind too would play for free in the same location, and when Moorcock asked if he could do some readings with them, the band jumped at the opportunity to get a bona fide sci-fi author on board.

Moorcock’s first impressions of the band are telling, describing them as “barbarians with electronics” and “like the mad crew of a long-distance spaceship who had forgotten their mission.” And when I interviewed him for the book, he admitted that Hawkwind felt like a band he’d conjured into existence, so perfectly did they fit into his entropic universe. The first piece he wrote and performed with them has become Hawkwind’s most iconic spoken word track: “Sonic Attack.” While its title is often used as short-hand for the brain-blasting shock and awe of Hawkwind in full flight, the track itself is all creeping dread and terror, a blackly comic parody of WW2 propaganda broadcasts distorted by the chilly logic of the Cold War, and very much a piece of New Wave SF.

Of course, discovering Moorcock’s connection with Hawkwind further piqued my interest in the band. As a young teen, I had moved seamlessly from reading Target’s Doctor Who novelizations to greedily consuming Moorcock’s Eternal Champion books. At the same time, it was becoming apparent that the one thing I was really interested in was music, and coming from a market town in the East Midlands, this almost inevitably meant heavy metal. If you combine those elements together, then it almost inevitably leads you to Hawkwind, particularly their early ‘80s incarnation. Yet even if you weren’t a big music fan, but were the type of young person who dug SF, Hawkwind would still find you one way or another, so embedded were they in British sci-fi and fantasy culture.

Of course, discovering Moorcock’s connection with Hawkwind further piqued my interest in the band. As a young teen, I had moved seamlessly from reading Target’s Doctor Who novelizations to greedily consuming Moorcock’s Eternal Champion books. At the same time, it was becoming apparent that the one thing I was really interested in was music, and coming from a market town in the East Midlands, this almost inevitably meant heavy metal. If you combine those elements together, then it almost inevitably leads you to Hawkwind, particularly their early ‘80s incarnation. Yet even if you weren’t a big music fan, but were the type of young person who dug SF, Hawkwind would still find you one way or another, so embedded were they in British sci-fi and fantasy culture.

Working my way through Moorcock’s dizzying output—how had this man managed to produce so many books?—meant regular visits to the local library, which also had an eclectically stocked record section, and it was here that I had my next close encounter with Hawkwind. Flicking through the racks, I was literally stopped in my tracks by the front cover of their 1973 live album Space Ritual. Etched in retina-sizzling technicolor, and featuring a stylized cosmic messiah flanked by gape-mouthed star cats, it was as though I’d stumbled across some bizarre alien artifact. Like a portal to another world, it was illustrated and designed by Colin Fulcher, aka Barney Bubbles, the man responsible for creating Hawkwind’s striking visual identity, from record sleeves, posters, and adverts. He even painted their equipment. As both a skilled professional designer and mystically-inclined freak, Bubbles was instrumental in creating an image for the band as sci-fi warriors and sages waging a sonic assault on the staid conventions of the straight world.

Hearing Space Ritual for the first time is an unforgettable experience. Lemmy—perhaps the band’s most famous ex-member—memorably described Hawkwind as being “a black fucking nightmare – a post-apocalypse horror soundtrack,” and this was surely the album he had in mind when he made that comment. It begins with what sounds like some deep space transmission, a massive interstellar hulk slowly heaving into view, before the ship’s grimy engines fire and you’re pushed back into your seat by the inertial intensity of opening track “Born To Go.” It’s dark, dense, and blurry, a nuclear-powered battering ram smashing through the cosmos, threatening to tear a hole in the fabric of space-time.

I can’t say it was love at first hearing, because it felt so outside my normal listening experience then, which was the relatively polite hard rock pyrotechnics of bands such as Rainbow and Judas Priest. But as I was eventually to realize, Space Ritual simply doesn’t sound like anything else, certainly not any other band. Yet staring at that sleeve as the record’s strange combination of cyclical riffs, chanted vocals, and electronic bleeps, howls, and whooshes poured out of the speakers, the thing it did sound like was science fiction—futuristic and dystopian, but with a vague sense of wonder still peeking through the cosmic gloom. And that was before “The Awakening,” the first spoken word piece on the album, and my first encounter with Robert Calvert, space-age poet extraordinaire.

More so than even Moorcock and Bubbles, Calvert was the man responsible for transforming Hawkwind into a science fiction band, first building a mythos around them as star-faring freedom fighters and prophets, then using SF as a vehicle for satire and social comment in the latter half of the 1970s, when he became their full-time singer and frontman. One of the first things he did for the band was to create (alongside Bubbles) The Hawkwind Log, a booklet that came with 1971’s In Search Of Space album. It tells the discontinuous, Burroughs-esque story of Hawkwind’s mission to liberate the human race from its essential emptiness, but sees them compressed “into a disc of shining black, spinning in eternity.” This depiction of Hawkwind as space travelling saviors puts the band themselves at the heart of an SF-inspired narrative, rather than merely writing songs about flying saucers and aliens.

More so than even Moorcock and Bubbles, Calvert was the man responsible for transforming Hawkwind into a science fiction band, first building a mythos around them as star-faring freedom fighters and prophets, then using SF as a vehicle for satire and social comment in the latter half of the 1970s, when he became their full-time singer and frontman. One of the first things he did for the band was to create (alongside Bubbles) The Hawkwind Log, a booklet that came with 1971’s In Search Of Space album. It tells the discontinuous, Burroughs-esque story of Hawkwind’s mission to liberate the human race from its essential emptiness, but sees them compressed “into a disc of shining black, spinning in eternity.” This depiction of Hawkwind as space travelling saviors puts the band themselves at the heart of an SF-inspired narrative, rather than merely writing songs about flying saucers and aliens.

It was Calvert who had come up with the concept behind the Space Ritual tour—the dreams of a crew of starbound explorers held in suspended animation—but even if the idea of staging a “space opera” was ultimately abandoned, traces of its storyline are still discernible, particularly in “The Awakening.” Calvert had first appeared on stage with Hawkwind reading his poems between songs, with “The Awakening” being part of a longer piece entitled “First Landing On Medusa.” Against plaintive warbles from the electronic chorus line, Calvert contemplates the cryogenically frozen members of his crew, his voice a chilly combination of precision and dispassion, his words full of ear-catching rhymes and imagery: “The nagging choirs of memory / The tubes and wires worming from their flesh to machinery / I would have to cut.” In the concluding part of the poem, the crew set foot on Medusa, and are quickly turned to stone.

There are a number of other readings from Calvert on the album that firmly locate the band in the New Wave SF universe of Ladbroke Grove. There’s the aforementioned “Sonic Attack,” bleakly Darwinian instructions for surviving a future war—“Do not panic! Think only of yourself!” —delivered by Calvert with malicious intent. “The Black Corridor,” another Moorcock piece that uses the opening lines of his novel of the same name, is typical of Hawkwind’s take on space as “a remorseless, senseless, impersonal fact.” And there are two other Calvert-penned pieces: “10 Seconds Of Forever” is a countdown through the last moments of someone’s life, while “Welcome To The Future” is a concentrated hit of eco-terror—“Welcome to the oceans in a labelled can / Welcome to the dehydrated lands.” Both are indebted to the apocalyptic landscapes of Ballard’s inner space.

But it wasn’t just Calvert writing from a science fictional perspective, with Space Ritual also highlighting other members’ take on the genre. Band leader Dave Brock had been writing in a paranoid, pessimistic vein from the first album onwards, with “Time We Left This World Today” neatly encapsulating Hawkwind’s philosophy of radical escapism, decrying an oppressive society controlled by “brain police” and calling for immediate off-world evacuation. Similarly, saxophonist and singer Nik Turner expresses a desire not to “turn android” and recommends flight in “Brainstorm,” while “Master Of The Universe” finds the alien demi-god of the title sorely disappointed by the affairs of man: “If you call this living, I must be blind.”

By the time that Hawkwind played the shows that would be recorded for Space Ritual in late 1972, they were by far the biggest band in the UK’s underground scene, performing to thousands of fans every night—in fact, with the unexpected success earlier in the year of their single “Silver Machine,” which got to number three in the charts and would go on to sell a million copies worldwide, Hawkwind were in danger of becoming a mainstream rock act. But if their science fiction associations enamored them to their fanatical following, who were more than happy to buy into their mythos, it both bemused and intimidated the music press, who continually wrote them off as, at best, a “people’s band,” at worst, a joke.

By the time that Hawkwind played the shows that would be recorded for Space Ritual in late 1972, they were by far the biggest band in the UK’s underground scene, performing to thousands of fans every night—in fact, with the unexpected success earlier in the year of their single “Silver Machine,” which got to number three in the charts and would go on to sell a million copies worldwide, Hawkwind were in danger of becoming a mainstream rock act. But if their science fiction associations enamored them to their fanatical following, who were more than happy to buy into their mythos, it both bemused and intimidated the music press, who continually wrote them off as, at best, a “people’s band,” at worst, a joke.

While rock culture itself still liked to adopt an “outsider” stance, even as it transformed into a multi-million dollar industry, science fiction remained a proper outsider culture in the ‘70s (pre-Star Wars), and was for the most part looked down on by the critical establishment. Yet for a lot of young people, rock and SF shared similar characteristics and attractions—as well as both being escapist mediums, they were also forward moving and excited by the idea of the future, a disruptive threat to straight society’s status quo. While both could be garish and naïve, they were also capable of smuggling new ideas and perspectives into consumers’ heads. And books such as Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings (first published in paperback in 1965), Heinlein’s Stranger In A Strange Land (1961), and Herbert’s Dune (1965) had been foundational texts of the original psychedelic counterculture, depicting battles between old and new worlds, and anticipating the coming of revolutionary messiahs.

From the late ‘60s onwards, during Britain’s progressive rock era, there were plenty of bands who included songs with science fictional themes in their repertoire: Pink Floyd’s “Let There Be More Light,” Van Der Graaf Generator’s “Pioneers Over C,” Black Sabbath’s “Into The Void,” Genesis’s “Watcher of The Skies,” etc. And some of the cover art of the time suggested an engagement with the fantastical, Roger Dean’s sleeves for Yes in particular, plus the covers to ELP’s Tarkus and Brain Salad Surgery (the latter illustrated by Alien designer H.R. Giger). David Bowie was also adept at sneaking SF-related themes into his work—“Space Oddity,” “Starman,” “1984,” etc.—and took the lead role in Nic Roeg’s cerebral SF flick The Man Who Fell To Earth (Hawkwind appeared in Robert Fuest’s adaptation of Moorcock’s The Final Programme, but literally for the blink of an eye). And both avant-jazz pioneer Sun Ra and French art proggers Magma drew inspiration from the idea of leaving Earth and setting up home on a new world.

But it was only Hawkwind who specifically defined themselves via numerous SF tropes, who sounded like the roaring of a mighty spacecraft, whose visual imagery was full of galactic heraldry and pulp magazine homages, and who actually had a series of post-apocalyptic SF novels written about them, where they effectively save the world. It’s what makes them the ultimate science fiction band, adding a cosmic spin to the turbulent “no future” culture of 1970s Britain.

Once I’d fully digested Space Ritual, and recognized it for the towering work of outsider genius that it clearly was, I needed more Hawkwind in my life. And as luck would have it, the next item I bought was a “twofer” cassette of the band’s late ‘70s albums, Quark, Strangeness And Charm (1977) and PXR5 (1979). Having achieved some kind of space rock singularity on Space Ritual, Hawkwind’s music became (relatively) more nuanced through the middle part of the decade and veered into fantasy territory (see Warrior)—but when Robert Calvert re-joined them as full-time singer and conceptualist, the band’s profile as sci-fi provocateurs par excellence was boosted once more.

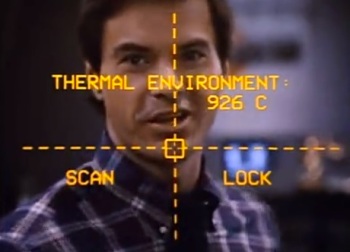

Quark and PXR5 are full of songs animated by Calvert’s quicksilver imagination, one which had moved on from early Hawkwind’s millenarian space chants to embrace SF as the New Wave had intended, as a way of interrogating the modern world and unravelling the technocratic, sometimes psychopathic, forces that increasingly ruled it. “Spirit Of The Age” is the band’s defining song from this era, a vision of the future where bored astronauts light years from home make love to android replicas of their long dead girlfriends, only to complain, “When she comes, she moans another’s name.” It’s also a paean to the plight of the clone, where individuality is unattainable: “Oh for the wings of any bird / Other than a battery hen.”

On saying that, “Uncle Sam’s On Mars” pushes it close, Calvert’s angry take-down of (as he saw it) America’s colonialist approach to space exploration, including pops at its fast food culture and consumerist worldview. He also presciently makes reference to global warming—“Layers of smoke in the atmosphere / Have made the earth too hot to bear”—and suggests that the money and technology involved in putting a man on Mars would be better used repairing our own planet. This was also the period of Hawkwind when the titles of classic sci-fi novels would be co-opted by Calvert as a springboard for his lyrics—in the case of “Damnation Alley” and “Jack Of Shadows” (both Roger Zelazny books), this resulted in reasonably faithful interpretations of the stories, whereas for “High Rise,” just the title of Ballard’s novel was taken. A personal favorite of mine is “Robot,” which references Asimov’s Three Laws, but riffs on the idea of the white collar suburban worker as a slave machine to capitalism.

The Atomhenge tour, 1976

Calvert left Hawkwind in 1979, and, in truth, the band would never subsequently pull off the rock + science fiction equation as inventively and authentically as when he was on board. But in the wider scheme of things, it didn’t particularly hinder the band’s progress, so strong was their brand with the people that mattered—their fans. In fact, the clutch of albums they released after Calvert’s departure all charted higher than Quark or PXR5—while both are now rightly regarded as highlights of the band’s back catalog, it’s possible that at the time they were just too literary in places, Calvert’s clever wordsmithing obstructing the flow of Hawkwind’s sonic attack.

And that takes us now to me sitting in my bedroom with that twofer in my hand, wondering what to listen to next. So I checked out what they were currently doing, and that meant 1982’s double-headed offering of Church Of Hawkwind and Choose Your Masques. The former is more electronically-inclined, while the latter is almost cosmic industrial, but they still contained those sci-fi rock essentials of engine room rhythms, distress call synth, robot vocals, future-themed lyrics, and all recorded the day after tomorrow. And Choose Your Masques in particular had a very cool sleeve. These albums might have lacked the finesse and sophistication of the Calvert era, but Hawkwind still sounded like no other band.

And that’s surely why they’ve continued to this day. They’ve certainly stretched the space rock template along the course of their journey, absorbing techno and ambient influences, especially during the ‘90s, but they’ve consistently traded in science fictional imagery and themes without ever having to resort to trad rock subject matter or the need to be more commercial, contemporary, or “edgy.” They’ve had their wilderness years, but the last decade has seen a significant revival of their fortunes, with perhaps the stand-out release from this period being The Machine Stops (2016), a concept album based on E.M. Forster’s story of civilization living inside a vast mechanical hive—its citizens are electronically connected, but they live alone in their cells.

Michael Moorcock once said that science fiction and rock ‘n’ roll were the two great despised art forms of the 20th century. It’s no wonder then that Hawkwind, in which the combination of the two reached its apotheosis, have come in for so much grief throughout their existence. But as my teenage self would have told the haters, you’re entitled to your opinion, but you’re missing out on something really quite special.

Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground – Radical Escapism In The Age Of Paranoia by Joe Banks is published by Strange Attractor.

Joe Banks is a London-based music writer whose work has appeared in various publications, including The Guardian, MOJO, Prog, Shindig!, Electronic Sound, and The Quietus. Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground is his first book. For endless Hawkwind trivia, follow him on Twitter: https://twitter.com/JoeBanksWriter.

Joe Banks is a London-based music writer whose work has appeared in various publications, including The Guardian, MOJO, Prog, Shindig!, Electronic Sound, and The Quietus. Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground is his first book. For endless Hawkwind trivia, follow him on Twitter: https://twitter.com/JoeBanksWriter.

![]() Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.

Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.