Halloween Horror '86

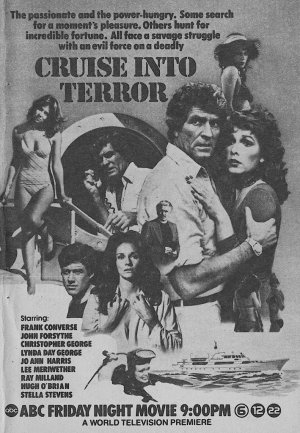

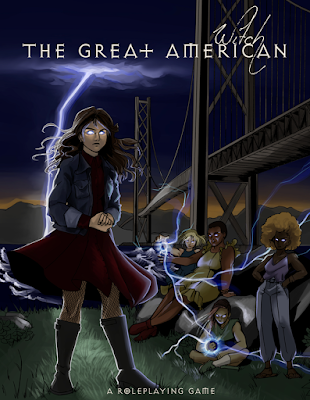

The Dare is a Call of Cthulhu scenario which very much wears its influences on its sleeve. It is a horror scenario of Cosmic Horror, so obviously H.P. Lovecraft and Call of Cthulhu. It is a haunted house scenario, so obviously any number of haunted house horror films and short stories, but also—just a little bit, ‘The Haunting’, the classic introductory scenario for Call of Cthulhu, which goes all of the way back to 1980 and Call of Cthulhu, First Edition. It is inspired by Call of Cthulhu, Third Edition, Call of Cthulhu, Fourth Edition, and Call of Cthulhu, Fifth Edition—certainly for its look. It is inspired by the horror films of the late 1970s and 1980s, including Halloween, Poltergeist, Evil Dead, The Lost Boys, and more. Above all, it is inspired by the kids’ adventure and kids in peril films of the 1980s, so The Goonies, Stand By Me, Monster Squad, E.T., and more. This rich source of inspiration has been mined in recent years by Roleplaying Games such as Free League Publishing’s Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the '80s That Never Was, Renegade Game Studios’ Kids on Bikes, and Bloat Games’ Dark Places & Demogorgons: The Roleplaying Game, but also most obviously on the silver screen by Stranger Things.

The Dare is a Call of Cthulhu scenario which very much wears its influences on its sleeve. It is a horror scenario of Cosmic Horror, so obviously H.P. Lovecraft and Call of Cthulhu. It is a haunted house scenario, so obviously any number of haunted house horror films and short stories, but also—just a little bit, ‘The Haunting’, the classic introductory scenario for Call of Cthulhu, which goes all of the way back to 1980 and Call of Cthulhu, First Edition. It is inspired by Call of Cthulhu, Third Edition, Call of Cthulhu, Fourth Edition, and Call of Cthulhu, Fifth Edition—certainly for its look. It is inspired by the horror films of the late 1970s and 1980s, including Halloween, Poltergeist, Evil Dead, The Lost Boys, and more. Above all, it is inspired by the kids’ adventure and kids in peril films of the 1980s, so The Goonies, Stand By Me, Monster Squad, E.T., and more. This rich source of inspiration has been mined in recent years by Roleplaying Games such as Free League Publishing’s Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the '80s That Never Was, Renegade Game Studios’ Kids on Bikes, and Bloat Games’ Dark Places & Demogorgons: The Roleplaying Game, but also most obviously on the silver screen by Stranger Things.So The Dare is a scenario for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, in which the players take the role of preteens who are dared by a school bully to enter a haunted house on Halloween. Published by Sentinel Hill Press—best known as the publisher of the Arkham Gazette, following a successful Kickstarter campaign, The Dare is written by Call of Cthulhu veteran Kevin Ross. Designed as a one-shot, ideally for four or five kids and ideally to be played on Halloween, it began life as a tournament scenario, which has now been updated to be run for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. As a one shot set in the eighties, The Dare works as a palette cleanser for veteran players, likely going all in on the period motifs—Sony Walkman, leg warmers, genre knowledge gleaned from video nasties, and so on, but it also works as an introduction to Call of Cthulhu for new players, made all the easier by its parred back ‘The Call of Kid-thulhu’ mechanics designed to fit the genre. It could in fact, be the defining experience with Cosmic Horror for the kid investigators, who as adults grow up to become investigators into the Mythos in the nineties, noughties, and beyond!

The set-up for The Dare is simple. School bully Roger Simmons has dared several of his victims to enter the Barnaker House, an abandoned and dilapidated home on the edge of town, and spend not just any night there, but Halloween! As the house wheezes and groans around them, their senses assaulted by the stench of mould and decay, of animal urine and faeces, the sound of scuttling in the walls and from room to room as the light from their torches skitter about them, a storm blows up and it looks like the investigators are there for the long haul… As they suffer the taunts and jibes of their bully, will the investigators find out if the house is really haunted? What horrors await them as they try to last the night?

To support this, The Dare is fully plotted out together with floor plans of the Barnaker House, stats and descriptions of all of the NPCs and the monsters. This includes suggestions as to what the NPCs will do location from location, but also gives suggestions as to how to adjust the tone of the scenario from location to location. These are set at the US film ratings of PG and R, the former minimising the violence, the gore, and the death, emphasising menace and anxiety, the latter being more visceral in its inclusion of gore, violence, and injury. Essentially, the difference between The Goonies and Evil Dead.

Mechanically, The Dare uses the Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition rules. It presents the core rules to the roleplaying game, but it also strips them back to present what it calls ‘The Call of Kid-thulhu’, a simplified version of the rules. Notably, the rules condense the eighty or so skills of Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition down to just fifteen. So instead of Psychology, Be a Pal, Be Bossy rather than Intimidate and Persuade, Sneaky in place of Sleight of Hand and Stealth, and Spooky Stuff rather than Occult and Cthulhu Mythos. The most notable addition to these skills is Play with Matches, which covers setting things alight, building traps, using chemicals, and so on, all of which should serve as a spur for the investigators’ invention. Overall, these stripped-down rules could easily be used to run other ‘The Call of Kid-thulhu’ type scenarios, or even slotted into an anthology of ‘Gateway’-type scenarios in which the investigators are kids.

Rounding out The Dare is a short essay by Brian M. Sammons, ‘Grab the Machete or: How I Learned to Stop Going Insane and Love 80s Horror Movies’. It provides a brief overview of the genre and suggests ten films that the Keeper and her players should watch as inspiration. The Dare also comes with ten ready-to-play ‘The Call of Kid-thulhu’ investigators. These are all designed to be played as girls or boys, and come with alternative names and space for boy or girl photos. There are some thirty or illustrations included in the pages of The Dare—each based upon a photograph submitted by one of the Kickstarter backers, which can be used by the players to illustrate their kid.

In terms of its horror, The Dare really revolves around its PG and R ratings and the classic confined space of the haunted house. Played using just the PG rating and it would even work as a scare ridden one-shot suitable for a younger, even preteen audience. Switched to the R rating and The Dare becomes a more visceral affair, much in the mode of the film It—though without the coulrophobia—and so is better suited for mature players. For the Keeper there are plenty of staging notes throughout, though she will need to handle one NPC with care. One option might be for the NPC to be played as a Player Character Investigator working hand-in-hand with the Keeper, but if not, and the players work out what is going on beforehand, it really is up to them to roleplay within the genre until their Investigators know.

Physically, The Dare stands out because although written for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, the layout for it is of Call of Cthulhu, Third Edition. It not only fits the period setting of the scenario, but it fits the scenario’s sense of nostalgia too and gives it a certain, delightful charm. The maps are perhaps a little plain and it needs a slight edit in places, but the artwork is excellent. The theme is applied to the front and back cover, which is done as the cover of a video cassette.

The Dare is a superb one-shot, one that manages the odd combination of being both nasty and charming, all infused with eighties nostalgia, from start to finish. Not just in the style of the story, its tone, and set-up, which can be creepy or horrible depending on the rating selected, but very much with its look. The Dare also suggests a style of play and provides a set of mechanics to support that, both of which deserve revisiting in future releases. Whether you are visiting the eighties for the first time or going back again for another go around, The Dare successfully double dares you with a one-shot of Halloween horror.