In Search of Nocticula

I want to introduce what I hope will be a new semi-regular feature here at the ole' Other Side.

"In Search of" will delve into odd, esoteric topics from my games in search of their origins and their relationship to myths, legends or even just a good story. The obvious tribute to the old 70s-80s TV series "In Search of..." featuring Leonard Nimoy. I am going to go back and retag some posts with this new "In Search of" label since this is not really a new idea for me. My hope here is this takes the place of "One Man's God" in my rotations of posts.

Let us start my first In Search of looking for a demon who captured my attention back in the 1980s.

Back in the Monster Manual II days, we were treated to a long list of demons that were also powerful members of the abyssal Hordes. These included a few demon lords (L) and oddly enough some that were tagged as being female (F). It seems odd to call that out now, but this was the 1980s.

But that is not why I am posting today. I was cleaning up some minis the other days and noticed one in particular. Maybe because I have been thinking of various monsters and monster books I decided to go back to an old search.

Who Is Nocticula: Part 1 History

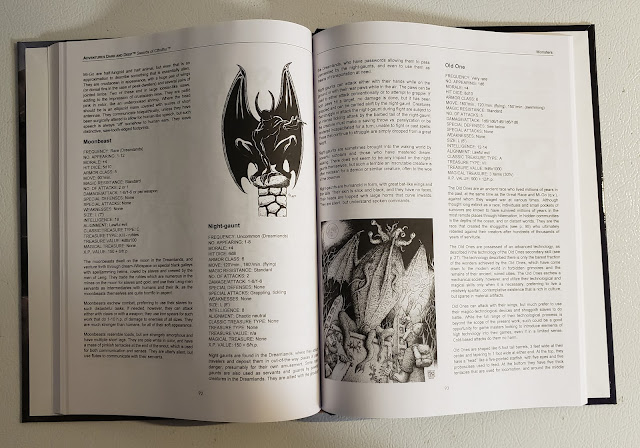

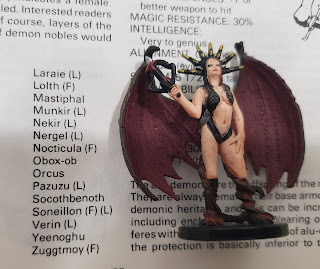

This is the mini and an entry in question.

Originally she was obviously some sort of demon related to the night. She is not listed as a "Lord" so we assume she must be of higher rank along with Lolth and Zuggtmoy.

Obviously, the name caught my attention then as it does now. Though there is almost nothing about her in any products outside of the MMII.

She does get name-dropped in the 1981 made-for-TV horror movie Midnight Offerings. When I saw it back in 2019 I wondered at the time if Gygax/TSR got the name from the movie. Though now it seems likely the name came from various occult books from the 1970s.

It would not be until the 1990s that I would run across her again.

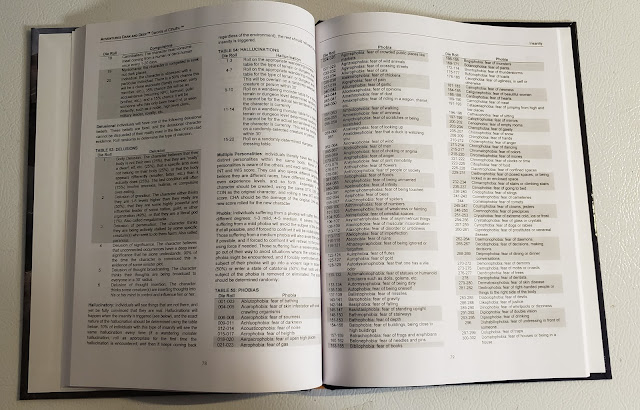

My first encounter with her was during the Netbook craze of the Pre-OGL Internet. While many people were still blissfully unaware of what the Internet could do AD&D players were on LISTSERVs on Bitnet sharing "Netbooks." These fan mad creations often lacked any sort of editorial control, art, or often even playtesting. But they made up for all of that in pure enthusiasm. If you were lucky you found one that had been formatted like a "real book" in Microsoft Word 2.0. One such book was "The Complete Netbook of Demons and their Relatives." This ancient and dusty tome was full of new demons. It was a great little treasure, to be honest. It did have an entry for Nocticula and Socothbenoth (I'll get to why that is important later). Their entries were:

Nocticula(F)-a patron of witches. Could only find one reference on her....

Socothbenoth-Another female (harem) like deity turned into a male demon.

That obviously had my attention. So I was already doing deep dive research into witches at this point for my "Netbook of Witches and Warlocks" so I added her name as one to be on the lookout for. Now keep in mind that at this time people were very, very wary of being sued by TSR for any copyright violations. So I had no real plans to use Nocticula in my books, I was just curious about her.

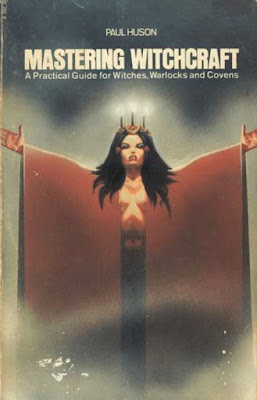

That obviously had my attention. So I was already doing deep dive research into witches at this point for my "Netbook of Witches and Warlocks" so I added her name as one to be on the lookout for. Now keep in mind that at this time people were very, very wary of being sued by TSR for any copyright violations. So I had no real plans to use Nocticula in my books, I was just curious about her.In my reading, I came across "Mastering Witchcraft: A Practical Guide for Witches, Warlocks, and Covens" by Paul Huson, 1970. Nocticula is mentioned many times. Likely as a "dark aspect" of Hecate or Habondia (or Habundia). That name is not in my "Dictionary of Classical Mythology" by J.E. Zimmerman. Huson adds that Noctiula is "Ruler of the Dead and Warden of the Tower Adamantine" and she walks at night. He also claims that the title of "Nocticula" meaning "little night" comes from the 12th century.

I do have to admit that the paperback cover of Mastering Witchcraft makes for a good depiction of Nocticula.

Gerald Gardner, the father of modern Wicca, even mentions her in his "Witchcraft Today" (1954). He also associates her with the figure of Bensozia. I guess that removes the fear of copyright issues, but I was still hesitant to use her preferring to come up with my own.

While all this is going on I got a copy of Dungeon #5 and found the adventure with Shami-Amourae, the demon queen of Succubi. She, along with Nocticula and Malcanthet have all been contenders for the title "Queen of the Succubi."

This bit didn't last long really and with the publication of Green Ronin's Armies of the Abyss and later the Book of Fiends we get a new look on Nocticula.

Part 2: Green Ronin & The d20 Years

Part 2: Green Ronin & The d20 YearsGreen Ronin brought Nocticula into the new Millennium with the various fiend books. Chris Pramas had worked on a few Planescape and devil-related books for Wizards of the Coast in the waning years of TSR. So he was in a great position to bring all of that knowledge to Green Ronin during the d20 boom. Armies of the Abyss (2002) covered demons and introduced us to a new Nocticula. Or rather, gave us Nocticula since so little detail had really been published about her so far. (Note. I am coming back to the Armies of the Abyss later in this series.)

Here she is demon lady of night yes, but also of women, dark fey, the natural world, psychotropic drugs, and earthly sensuality. Known as the Princess of Moonlight she revels in all things pleasurable, earthly, and chaotic. She very much is the patroness of "living deliciously." The description of her followers can only be described as "witches."

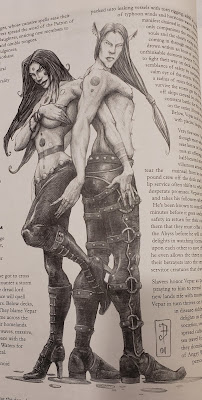

She has a twin brother, Socothbenoth, the demon lord of perversion, with whom she has an incestuous relationship with. Socothbenoth is basically the mind of Aleister Crowley in the body of Lord Byron and the sexual appetites of both.

I have used him before as a witch's patron based on the movies Byleth: The Demon of Incest (1972) and Il Sesso Della Strega (1973).

She only gets a mention in Fiendish Codex I: Hordes of the Abyss, a little more than what she got in the MMII nearly 20 years prior. She gets the title "The Undeniable" and her concerns are "Night" and she makes her realm on the 72nd layer of the Abyss called Darklight.

Part 3: Pathfinder

Our Queen of the Night fares better in her Pathfinder version where she is a major Demon Lord. Her history is largely that of what was seen in the Green Ronin books. Indeed all of that is kept to the extent the OGL will allow. However, she is taken further in Pathfinder when she is given the ability to kill other demon lords. This gives her a connection to assassins.

Here she appeared in a number of Pathfinder products, in particular the Book of the Damned, which covered the demons and devils of the Pathfinder game.

At some point, she grew tired of killing demon lords and sought out redemption as the Goddess of Artists. I am not sure I completely like this idea, but hey Pathfinder can do what they like really.

Now to be fair, Pathfinder added a ton of material to Nocticula, and a lot of it is good. I could easily use any amount of it, to be honest.

Part 4: Nocticula in my World

I have a lot of great information and details. But not all of them are great for my games. So. How can I rebuild Nocticula for my games and in particular my War of the Witch Queens campaign?

Part of her background is she was one of the first Succubi. That's fine and all, but I feel there is a tendency to make a female demon a type of succubus. Sure I get it and her background supports it to a degree, but it feels lazy to me. I mean there are SO MANY "first" Succubi. There is Malcanthet, Shami-Amourae, Xinivrae, and Lynkhab. Do we need Nocticula to be a succubus? Not really.

I do like keeping Socothbenoth as her brother/lover. I like keeping them both as being fairly depraved as well. They are demons after all. I even like the assassin idea from later Pathfinder books. Given her name I would like to get back to her association to the night and things of the night. In some ways the evil counterpart to my Nox.

In this, Nocticula is the demon lord of Night. She is honored by witches, warlocks, prostitutes, and assassins. Anyone committing an evil act at night will say a benediction to Nocticula. She is the daughter of Nox by Camazotz, the demon lord of bats and vampires (or maybe Orcus?). She is the twin sister to and lover of the demon lord Socothbenoth (the demon lord of perversion).

Given that her first "D&D" appearance was in the Monster Manual II from 1983, I would draw on sources from 1982 and before for my influences on her.

Obviously, I would need to write her up for AD&D 1st Edition. I would use some of her Pathfinder details (what is allowed under the OGL) and go back to the earliest ideas about her.

--

NOCTICULA

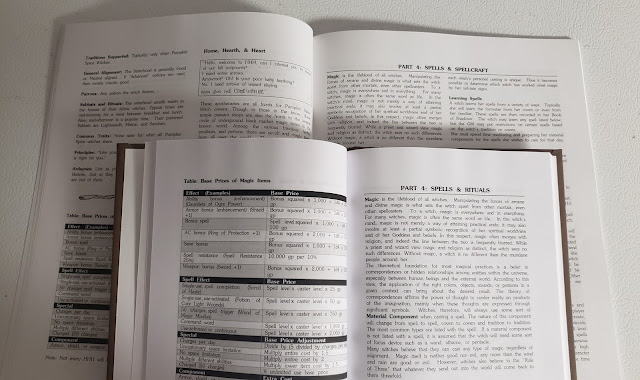

NOCTICULA FREQUENCY: Unique (Very Rare)NO. APPEARING: 1

ARMOR CLASS: -2

MOVE: 18" / 24" (MC: C)

HIT DICE: 13+39 (97 hp)

% IN LAIR: 0%

TREASURE TYPE: Q (x10), U

NO. OF ATTACKS: 2

DAMAGE/ATTACK: Whip 1d6+1d4 (fire) (x2)

SPECIAL ATTACKS: Witch spells

SPECIAL DEFENSES: +2 or better weapon to hit

MAGIC RESISTANCE: 25%

INTELLIGENCE: Genius

ALIGNMENT: Chaotic Evil

SIZE: M (6')

PSIONIC ABILITY: See below

LEVEL/X.P. VALUE: IX/8250 + 18/hp (9,996 xp)

Nocticula is the Demon Lady of the Night. Witches, warlocks, assassins, and all those who make illicit trades or bargains under the cover of darkness are her followers. She hears their prayers when none of the gods will. She is also the patron of creatures of the night like vampires, shadow creatures, and even alu-demons and succubi.

She will always appear as a very attractive member of the gender and species the observer prefers. In a mixed company, she will attempt to provide as many attractive qualities as she can. She can do this via a limited form of telepathic awareness that is not quite ESP. It is a subtle power, like many of her gifts, and can only be blocked by magic or psionic ability specifically designed to do so. It also gives her the ability to speak any language known.

Nocticula is a lover, but also a capable fighter. She wields a whip of fire that she can attack with twice per round. The whip will do 1d6 points of damage and the fire an additional 1d4. She can cast spells as a Mara Witch of the 13th level.

She also has the following spell-like powers.

- At will: Detect Good (Law), Detect Invisible, Detect Magic, Darkness 10' Radius, Glamour, Telekinesis (250 lbs / 25,000 GP weight), Tongues.

- 3 times per day: Astral Projection, Charm Monster/Person, Read languages, Read magic, Shape change, Teleport without Error, Trap the Soul.

- 1 time per day: Gate, Polymorph any object.

Like all demons, she is affected by acid, iron weapons, magic missiles, and poison, (full). Cold, electricity, fire (dragon, magical), and gas (half). She has 25% magic resistance, but this does not apply

She has wings, but these can be hidden away. Despite her appearances and appetites, she is not a succubus or any sort of Lilim. She does have many succubi attendants and servants. Her preferred servants though are humans and some elves and fae. She may gate in 1d6 Succubi or 1d8 alu-demons to aid her. These are from her personal retinue and not easily replaced. She can also summon 2d8 shadow demons to do her bidding. Either of these can be done once per day (1/day). She can compel any vampire she encounters (as a charm-like ability they are not immune to) to do her bidding, but she can't summon vampires.

Rumors of her always appearing nude when summoned were created by clerics and scholars who rarely left their scriptoriums. However, to approach her in her layer in the Abyss one must be completely unclothed. This includes armor and weapons.

Relationships

Nocticula has the best relationship with her brother and lover Socobenoth, the Demon Lord of Perversion. It is a good relationship as far as two chaotic evil demons can have. She respects Lilith, the Demon Queen as the two are fine as long as they remain out of each other's business. Her rivalry with, and enmity of, Malcanthet is legendary. Equally so is her distaste of the demon Lord Graz'zt but none remember how this all began. Her relationship with Camazotz is one of pure hatred and each hates the other's claim as the demonic patron of vampires. A hatred she does not extend to Lilith or even Orcus, whom she refers to as "Grandfather." Whether this is an acknowledgment of paternity or an honorific is unknown. Orcus also extends this recognition to Nocticula.

Unknown to most, Nocticula is an assassin of demon lords and even a minor god. She has discovered that when she kills them she can take on their powers. She successfully assassinated Vyriavaxus, the former demon lord of shadows. Now shadow demons begrudgingly show her patronage. Presently Nocticula sits and carefully plans her next kill.

--

Looking forward to seeing what I can do next in my new In Search Of feature.

--

Links

- The Greyhawk Wiki

- The Succubus Wiki

- Pathfinder SRD

- Pathfinder Wiki