On the tail of Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with

Chess and

Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showcased how another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—

Dungeons & Dragons,

RuneQuest, and

Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

Since 2008 with the publication of

Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one

Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will be compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it.

Labyrinth Lord and

Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has

Swords & Wizardry.

Black Pudding is a fanzine that is nominally written for use with

Labyrinth Lord and so is compatible with other Retroclones, but it is not a traditional

Dungeons & Dragons-style fanzine. For starters, it is all but drawn rather than written, with artwork that reflects a look that is cartoonish, a tone that is slightly tongue in cheek, and a gonzo feel. Its genre is avowedly Swords & Sorcery, as much Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser as Conan the Barbarian. Drawn from the author’s ‘

Doomslakers!’ house rules and published by

Random Order via

Square Hex,

Black Pudding’s fantasy roleplaying content that is anything other than the straight-laced fantasy of

Dungeons & Dragons, but something a bit lighter, but still full of adventure and heroism. Issues

one,

two, and

three have showcased the author’s ‘Doomslakers!’ house rules with a mix of new character Classes, spells, magic items, monsters, NPCs, and adventures.

Black Pudding #4 included a similar mix of new Classes, NPCs, and an adventure, but also included the author’s ‘OSR Play book’, his reference for running an Old School Renaissance game, essentially showing how he runs his own campaign. Published in August 2018,

Black Pudding #5 is more of a return to form, a mix of new character Classes, spells, magic items, monsters, NPCs, and adventures. It does, however, begin to suggest a campaign setting.

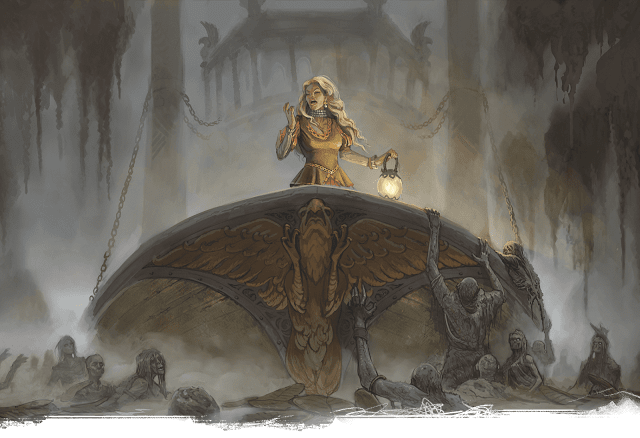

Black Pudding #5 opens with ‘Standing Stones of Marigold Hills’. This is a mini-sandbox consisting of a series of hills strewn with tombstones and graves, with many of the latter occupied with the undead and the region by the spirits of the dead. Some of these occupants are given thumbnail descriptions for easy portrayal by the Labyrinth Lord. The tombstones were once tended to by the Marigold Witch, but although she is long gone, it is said that she left her spellbook behind. Perhaps it is in one of the tombs?

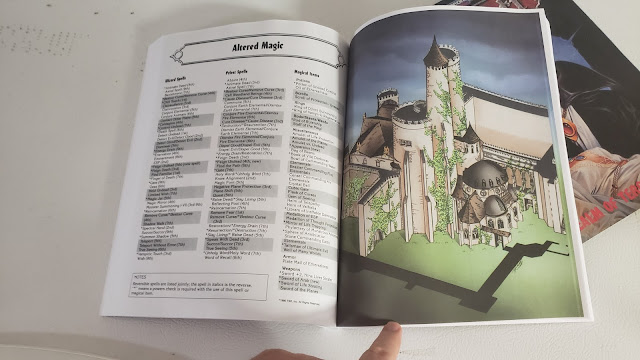

The Book of Marigold is also detailed as is the fact that it will avoid being ‘captured’ and the three spells it contains. These spells are cartoonishly inventive, such as

Arrow Road, which creates path of arrows which the targets of the spell must follow, and

Marigold Charm, which creates a sphere of pungent aroma that renders those inside immune to poison, gas, and insect attacks, but at the cost of a reaction penalty and inability to surprise anyone.

The second adventure is ‘The Rat Queen Dies Tonight’, designed for Player Characters of Fourth and Fifth Levels. It is a thirteen-location, fairly linear cavern complex, sparsely written, but nicely detailed. The Player Characters trail a band of marauding rats to this complex and discover what appears to be at first a scavenged tomb then hot and steamy caves. The secret is that the Rat Queen has entered a pact with a demon and according to that pact, she dies tonight! Are the Player Characters the means of fulfilling that pact or is there another solution? There is lots of treasure to be found, including

Malefysto’s Grimoire of Nefarious Incantations, another book of spells. These are all fire-themed, such as

Malefysto’s Hands of Fire, which gives the caster flaming fists that he can even throw them like mini-fireballs, and

Malefysto’s Eyes of Doom which turns the caster’s eyes black and his gaze capable of vaporising anyone he looks upon! The spellbook will be a suitable reward for any Wizard, but there is plenty of treasure to go around and the scenario itself is fun.

‘Adventures in the North’. The details a small region taken from the land of Yria, the ‘Doomslakers’ campaign, dotted with independent villages and dwarf strongholds, the latter abandoned after the blue giants known as the Norg drove them out. Even now, the dwarves plan to take their lands back. It takes the traditional concept of the barbarian north and its frosty weather, adds big tables of encounters and rumours of the north, and new monsters and magical items. The new monsters include the Ice Witch, a twisted, cold-hearted woman who lives in an icy house or cloister with her sisters, can cast numerous cold and ice-themed spells, and can be healed from or even reflect cold attacks. When slain, they can rise again as Witch Wights which seek out the warmth of the living, and some Ice Witch matriarchs carry a

Staff of the Ice Witch, which will might freeze anyone who grasps it, can cast further spells than those of the Witch Wight, and once a month, conjure a blizzard! There is a lot packed into the four pages of this and it is great to some setting content from the author’s own campaign. Hopefully this will be supported with an adventure or two and more support in future issues.

Black Budding is renowned for its one-page, slightly tongue-in-cheek new character Classes and

Black Pudding #5 is no exception with a total of three. The first is the Ninja, which does everything you would expect. The Ninja cannot wear metal armour or wield two-handed weapons, but is good with ranged weapons, a better backstab attack than the Thief potentially inflicting a deathblow, is adept at stealth and can throw flash and smoke bombs. Each Ninja comes from one of eight Ninja Orders which sets certain requirements for being a Ninja, such as the Red Finger order requiring its members to wear red gloves and those of the Morbid Moons to honour the undead! The Ninja Class feels nicely done, but perhaps slightly overly potent in comparison to other Classes.

The Orbii is an ancient race of protectors, said to have served the Daughters of the Moon. They fight as Thieves, but each has a single special talent like being able to forge weapons and armour, including magical weapons and armour at Fifth Level or being able to track and forage. They can also pray to the Moon Goddess once per day to gain ‘Moon Luck’, such as a kiss which heals the supplicant or teleporting the character and his allies anywhere they like! The Boola is the buxom matron of wild places and mother to secrets, who fights as a Cleric, can listen to nature to learn its secrets, and is accompanied by one or more animal companions. Both are thematically strong, the Boola essentially a variant upon the Druid Class.

The monsters in the issue begin with a quartet of unconnected and a quartet of connected creatures. The former includes the Star Troll, wise in cosmic wisdom and with a penchant for Elf flesh; the Ipzee , a cave-dwelling many-toothed thing which cannot be pushed over, swallows its treasure, and whose teeth can be turned into wands; the Ninja Devil, packs of miniature devils which practice Ninjitsu and assassination; and the Angry Shell, a grumpy if multi-lingual sea beast with a great shell who hates to be disturbed, but which might be bribed to talk. The connected creatures are the Arqod Illuminara, the Arqod Champion, the Arqod Dreadling, and the Arqod Sauropod. The Arqod Illuminara are ancient mind-bending, hyper-intelligent humanoids from the time before, always accompanied by their fearsome zealot Arqod Champions, almost suicidal, perpetually hungry for live flesh (and brains and bones) Arqod Dreadlings, and perhaps riding a great Arqod Sauropod, whose ichor can be harvested for its magical properties, and when not serving as beast of burden, likes to play practical jokes by pretending to be small hills. There is something very much of the

Alien Universe in these creatures, the Arqod Illuminara being a little like the Engineer for example. Each of these creatures is accompanied by thumbnail descriptions—sometimes a little more, illustrations, and stats, all enough to be both entertaining and playable.

One of the best on-going features in

Black Pudding is ‘Meatshields of the Bleeding Ox’, a collection of NPCs ready for hire by the Player Characters (or in a pinch, replacement Player Characters). There is a decent range of NPCs given here, such as Iko Rain, a Fourth Level Ninja whose turn-ons are infiltration and turn-offs are yaks, turtles, and big fights, and The Beast of Bogl, a Four Hit Dice Beast who likes food and fighting, hates talking and not eating, and will not carry anything. Much like the monsters, they each come with full stats, thumbnail description and portrait, as well as a list of their abilities and how much they can be hired for. Unfortunately, seventeen is too many, just as they did in

Black Pudding #4, and as inventive and as fun as these are, they do begin to like place fillers rather than actual gaming content.

‘They Come… But What Are They?’ is a one-page NPC/monster generator. With a roll of a handful of dice, the Labyrinth Lord can create the encounter’ looks, alignment, magic, special defences and attacks, toughness, and more. It is quick and dirty and useful. Rounding out

The Black Pudding #5 is a quartet of detailed magical weapons. Zam is a +2 sword which can read magic and grant levitation once a day, but really wants to kill Dark Elves; Traumch, a Chaotic +2 battle axe which can smash armour and deals double damage against unarmoured opponents and the undead; and Riveredge and Moonbeam are +1 swords, the first granting water breathing, increased swimming speed, and the ability to walk on water, whilst the second inflicts double damage on lycanthropes and can capture moonlight and shine like a torch. All four are nicely themed and interesting enough that any character capable of wielding them would have fun with them. Lastly, on the back of the issue is a new character sheet for the retroclone, this time laid out as the face of the demon statue being plundered on the cover of the

Player’s Handbook for

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, First Edition. It is silly certainly, but a bit of fun, and a nice nod to the origins of the game.

Physically,

Black Pudding #5 adheres to the same standards set by the previous issues. So plenty of good, if cartoonish artwork to give it a singular, consistent look and lots of quite short articles, that are in places are underwritten. The obvious issue with

Black Pudding #5—and indeed, any of its issues, is that its tone may not be compatible with the style of

Dungeons & Dragons that a Labyrinth Lord or Game Master is running. The tone of

Black Pudding is lighter, weirder, and in places just sillier than the baseline

Dungeons & Dragons game, so the Game Master should take this into account when using the content of the fanzine, but

Black Pudding #5 does something that previous issues have to dated avoided. That is, showcase parts of the author’s ‘Doomslakers!’ campaign and that lifts

Black Pudding out of just being a madcap medley of monsters, Classes, and NPCs.

Again, just as in previous issues,

Black Pudding #5 has too many NPCs and whilst there is still room for ‘Meatshields of the Bleeding Ox’, it should ideally be reduced in size to make way for other content. Especially the author’s ‘Doomslakers!’ campaign which deserves more attention in the pages of the fanzine. Once again,

Black Pudding #5 combines a slightly gonzo style and look in a professionally published package offering fun new content and the promise of more of the ‘Doomslakers!’ campaign setting.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/kddo/knock-down-drag-out-1?ref=theotherside

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/kddo/knock-down-drag-out-1?ref=theotherside