Friday Fantasy: The Incandescent Grottoes

The Incandescent Grottoes is a scenario published by Necrotic Gnome. It is written for use with Old School Essentials, the Old School Renaissance retroclone based on the version of Basic Dungeons & Dragons designed by Tom Moldvay and published in 1980. It is designed to be played by a party of First and Second Level Player Characters and is a standalone affair, but could be connected to another scenario from the publisher, The Hole in the Oak. Plus there is scope in the adventure to expand if the Referee so desires. Alternatively, it could simply be run on its own as a self-contained dungeon adventure. The scenario is intended to be set underneath a great mythic wood, so is a perfect addition to the publisher’s own Dolmenwood setting, but would be easy to add to the Game Master’s own campaign setting. Further, like so many other scenarios for the Old School Renaissance, The Incandescent Grottoes is incredibly easy to adapt to or run using the retroclone of the Referee’s choice. The tone of the dungeon is weird and earthy, part of the ‘Mythic Underworld’ where strangeness and a degree of inexplicability and otherworldly dream logic is to be expected.

The Incandescent Grottoes is a scenario published by Necrotic Gnome. It is written for use with Old School Essentials, the Old School Renaissance retroclone based on the version of Basic Dungeons & Dragons designed by Tom Moldvay and published in 1980. It is designed to be played by a party of First and Second Level Player Characters and is a standalone affair, but could be connected to another scenario from the publisher, The Hole in the Oak. Plus there is scope in the adventure to expand if the Referee so desires. Alternatively, it could simply be run on its own as a self-contained dungeon adventure. The scenario is intended to be set underneath a great mythic wood, so is a perfect addition to the publisher’s own Dolmenwood setting, but would be easy to add to the Game Master’s own campaign setting. Further, like so many other scenarios for the Old School Renaissance, The Incandescent Grottoes is incredibly easy to adapt to or run using the retroclone of the Referee’s choice. The tone of the dungeon is weird and earthy, part of the ‘Mythic Underworld’ where strangeness and a degree of inexplicability and otherworldly dream logic is to be expected.The Incandescent Grottoes is, like the other official scenarios for Old School Essentials very well organised. The map of the whole dungeon is inside the front cover, and after the introduction, the adventure overview provides a history of the dungeon, an explanation of its factions and their relationships, and details—but definitely not any explanations—of its unanswered mysteries. The latter can be left as they are, unexplained, or they can be potentially tied into the rumours which will probably push the Player Characters into exploring its depths. Or of course, they can be tied into the Referee’s greater campaign world and lead to other adventures, or even developed from the players’ own explanations and hypothesises should the Referee be listening carefully. Besides the table of rumours, the adventure includes a listing of the treasure to be found in the dungeon and where, and a table of ‘Random Happenings’ (or encounters). These are not merely random encounters with wandering monsters, but a mix of those along with strange things like a sudden aura of cold that sends a shudder down the backs of the Player Characters or a floating skeletal hand which points to the nearest treasure before crumbling to dust.

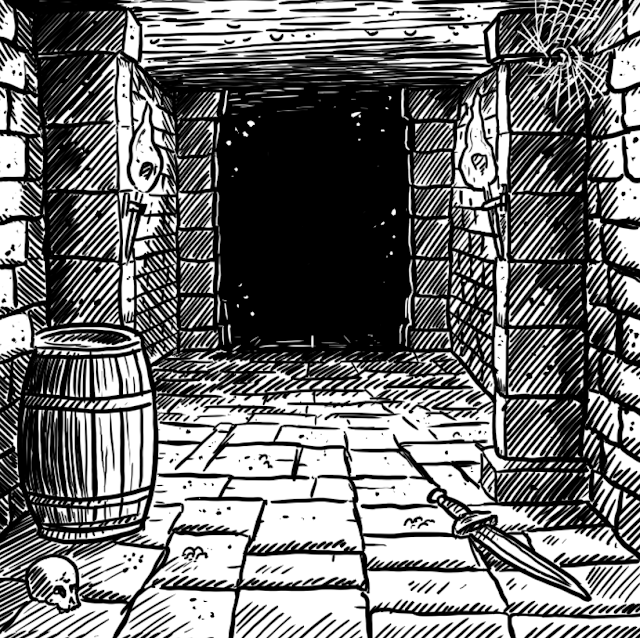

In between are the descriptions of the rooms below The Incandescent Grottoes. All fifty-seven of them. These are arranged in order of course, but each is written in a parred down style, almost bullet point fashion, with key words in bold with details in accompanying parenthesis, followed by extra details and monster stats below. For example, the ‘Ritual Robes’ area is described as containing “Dark stone blocks (pockmarked, walls, ceiling 10’). Green tiled floor (zig-zag pattern). Black robes (flank the corridor, hanging from hooks).” It expands up this with “North (from Area 16): Intermittent crackles and blues flashes.” It expands upon this with descriptions of the door to another area and what happens when the Player Characters examine the black robes. There is a fantastic economy of words employed here to incredible effect. The descriptions are kept to a bare minimum, but their simplicity is evocative, easy to read from the page, and prepare. The Incandescent Grottoes is genuinely easy to bring to the table and made all the easier to run from the page because the relevant sections from the map are reproduced on the same page. In addition, the map itself is clear and easy to read, with coloured boxes used to mark locked doors and monster locations as well as the usual room numbers.

In places though, the design and layout does not quite work. This is primarily where single rooms require expanded detail beyond the simple thumbnail description. It adds complexity and these locations are not quite as easy to run straight from the page as other locations are in the dungeon.

The dungeon itself is driven by factions and their associated rumours. The factions include a demonic cult that has all but collapsed, a band of troglodytes riven by factionalism, a Necromancer who is using the caves as a base of operations, an Imperial Illusionist hiding out, and more… All are given quite simple motivations and wants, often clashing with each other, so that when the Player Characters do interreact with them, the dungeon will come to life and be more than a simple series of rooms, traps, and encounters. The Incandescent Grottoes definitely has the feel of a location on the edge of abandonment, one which swings back and forth between the weirdness and whimsy of caves and grottoes run through with strange crystals and mushrooms and the corridors and rooms of worked stone. Notably, the areas previously occupied by the cult are laced with deadly traps and puzzles, only adding to the often highly dangerous nature of the dungeon. Whilst this deadly nature is befitting of the Old School Renaissance, arguably The Incandescent Grottoes verges on being too deadly and dangerous for First and Second Level Player Characters especially if run as a first-time dungeon for players new to the genre. If so, it is perhaps better run as the deadlier half of The Hole in the Oak. Of course, there will be plenty of Game Masters who will see this as a feature rather than a negative aspect of the adventure and so will not have the potential issue. Either way, The Game Master should at least know beforehand and once at the table, it will encourage careful play, just as any classic Old School Renaissance dungeon or scenario should, and the likelihood is that the Player Characters will be making two or three delves down into it before exploring its fullest reaches.

Physically, The Incandescent Grottoes is a handsome little affair. The artwork is excellent, the cartography clear, and the writing to the point.

The Incandescent Grottoes can be used as an introductory dungeon—and it would be perfect for that, but it begs to be worked into a woodland realm of its own, its various details and connected rumours used by the Referee to connect it to the wider world and so develop context. Whichever way it is used, The Incandescent Grottoes is a superbly designed, low level dungeon, full of whimsy and weirdness and fungal flavour and crystalline detail that bring its complex of caves and rooms alive, all presented in a format that makes it incredibly accessible and easy to run.

Requirements Your last action was to Raise a Shield. You adopt a wide stance, ready to defend both yourself and your chosen ward. Select one adjacent creature. As long as your shield is raised and the creature remains adjacent to you, the creature gains a +1 circumstance bonus to their AC, or a +2 circumstance bonus if the shield you raised was a tower shield.

Requirements Your last action was to Raise a Shield. You adopt a wide stance, ready to defend both yourself and your chosen ward. Select one adjacent creature. As long as your shield is raised and the creature remains adjacent to you, the creature gains a +1 circumstance bonus to their AC, or a +2 circumstance bonus if the shield you raised was a tower shield. Range 60 feet; Targets your familiar You draw upon your patron's power to momentarily shift your familiar from its solid, physical form into an ephemeral version of itself shaped of mist. Your familiar gains resistance 5 to all damage and is immune to precision damage. These apply only against the triggering damage. Heightened (+1) Increase the resistance by 2.

Range 60 feet; Targets your familiar You draw upon your patron's power to momentarily shift your familiar from its solid, physical form into an ephemeral version of itself shaped of mist. Your familiar gains resistance 5 to all damage and is immune to precision damage. These apply only against the triggering damage. Heightened (+1) Increase the resistance by 2.