#Dungeon23 Tomb of the Vampire Queen, Level 1, Room 11

Across from Room 10 is a similarly configured room.

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

Photo by Pixabay from PexelsA secret door in the floor reveals a sack of 150 GP. The coins are ancient and unknown to the PCs.

Original Roleplaying Concepts

Across from Room 10 is a similarly configured room.

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels

Photo by Pixabay from PexelsA secret door in the floor reveals a sack of 150 GP. The coins are ancient and unknown to the PCs.

Up from Room #8 and across from Room #9 is Room #10.

It appears to be of the same dimensions as the previous rooms 5 through 9.

Virgil Finlay

Virgil FinlayOnce the room is entered, a group of semi-human Phantoms appears.

The Phantoms can not attack, but a failed saving throw vs. Spells will cause anyone to run out of the room in fear. Once out of the room the fear effect dissipates.

They have 1-1 HD and 1 hp. Magic weapons are required to hit. There are 10 and their AC is 9.

The phantoms can be Turned by a cleric. A bless or dispel evil spell will also destroy them. The entire group is effected by these magics.

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

Name: The Souls of BriarcroftPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: The Souls of BriarcroftPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.Much like the Miskatonic Repository for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, the Jonstown Compendium is a curated platform for user-made content, but for material set in Greg Stafford’s mythic universe of Glorantha. It enables creators to sell their own original content for RuneQuest: Roleplaying in Glorantha, 13th Age Glorantha, and HeroQuest Glorantha (Questworlds). This can include original scenarios, background material, cults, mythology, details of NPCs and monsters, and so on, but none of this content should be considered to be ‘canon’, but rather fall under ‘Your Glorantha Will Vary’. This means that there is still scope for the authors to create interesting and useful content that others can bring to their Glorantha-set campaigns.

—oOo— What is it?

What is it?It is a fifty-two page, full colour, 32.56 MB PDF.

The layout is clean and tidy. The artwork is excellent.

Where is it set?

The Temple of Twins is set in Prax. It is a sequel, but not a direct sequel, to The Gifts of Prax and Stone and Bone.

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

50 Fathoms: High Adventure in a Drowned World was the second Plot Point setting to be published by Great White Games/Pinnacle Entertainment and the second Plot Point setting to published. Like the first, Evernight, it was published in 2003 and introduced both a complete setting and a campaign, in this case, a Plot Point campaign. A Plot Point campaign can be seen as a development of the Sandbox style campaign. Both allow a high degree of player agency as the Player Characters are allowed to wander hither and thither, but in a Sandbox style campaign there is not necessarily an overarching plot, whereas in a Plot Point campaign, there is. This is tied to particular locations, but not in a linear fashion. The Player Characters can travel wherever they want, picking up clues and investigating plots until they have sufficient links and connections to confront the threat at the heart of the campaign. In 50 Fathoms the threat consists of a trio of Sea Hags who are downing the world of Caribdus, literally under fifty fathoms!

50 Fathoms: High Adventure in a Drowned World was the second Plot Point setting to be published by Great White Games/Pinnacle Entertainment and the second Plot Point setting to published. Like the first, Evernight, it was published in 2003 and introduced both a complete setting and a campaign, in this case, a Plot Point campaign. A Plot Point campaign can be seen as a development of the Sandbox style campaign. Both allow a high degree of player agency as the Player Characters are allowed to wander hither and thither, but in a Sandbox style campaign there is not necessarily an overarching plot, whereas in a Plot Point campaign, there is. This is tied to particular locations, but not in a linear fashion. The Player Characters can travel wherever they want, picking up clues and investigating plots until they have sufficient links and connections to confront the threat at the heart of the campaign. In 50 Fathoms the threat consists of a trio of Sea Hags who are downing the world of Caribdus, literally under fifty fathoms! Traveller is one of the hobby’s oldest Science Fiction roleplaying games and still its preeminent example outside of licensed titles such as Star Wars and Star Trek. It is the roleplaying of the far future, its setting of Charted Space, primarily in and around the feudal Third Imperium is placed thousands of years into the future. Since its first publication in 1977, Traveller has been a roleplaying setting built around mercantile, exploratory, mercenary and military, and adventuring campaigns. Inspired by the Science Fiction of fifties and sixties, the rules in Traveller can also be adapted to other Science Fiction settings, though it requires varying degree of effort depending upon the nature of the setting. The Traveller: Explorer’s Edition is presented as introduction to the current edition of the roleplaying game, published by Mongoose Publishing. It is designed for scenarios and campaigns that focus on exploration beyond the frontier and provides the tools for such a campaign, including rules for creating Player Characters, handling skills and challenges, combat, spaceship operation and combat, plus equipment, animals, and the creations of worlds to explore.

Traveller is one of the hobby’s oldest Science Fiction roleplaying games and still its preeminent example outside of licensed titles such as Star Wars and Star Trek. It is the roleplaying of the far future, its setting of Charted Space, primarily in and around the feudal Third Imperium is placed thousands of years into the future. Since its first publication in 1977, Traveller has been a roleplaying setting built around mercantile, exploratory, mercenary and military, and adventuring campaigns. Inspired by the Science Fiction of fifties and sixties, the rules in Traveller can also be adapted to other Science Fiction settings, though it requires varying degree of effort depending upon the nature of the setting. The Traveller: Explorer’s Edition is presented as introduction to the current edition of the roleplaying game, published by Mongoose Publishing. It is designed for scenarios and campaigns that focus on exploration beyond the frontier and provides the tools for such a campaign, including rules for creating Player Characters, handling skills and challenges, combat, spaceship operation and combat, plus equipment, animals, and the creations of worlds to explore. What is it?

What is it? On the glacier moon of Myung’s Misstep, perpetually enshrouded in ice and snowstorms, the Player Characters have been contracted to transport and guard a locked box from Out of Order, the site of the moon’s still not functioning space elevator to the water-farm town of Plankton Downs. The safest means of travel is aboard a low-bodied hovercraft fitted with a heat spike it can use to anchor itself when a severe storm strikes. The Player Characters are booked aboard the Nantucket Sleigh Ride, one of these vessels with an adequate record in terms of punctuality, safety, and comfort. If the Player Characters are expecting a thoroughly uninteresting journey, then they are going to be disappointed. Amidst all of the colonial cyborgs, Martian nuns, alien tourists, and macrame owls aboard, a body is found missing its head! Then another one! And the way they died, their heads are all mangled... Could a monster out of galactic myth be stalking the halls and cabins of the Nantucket Sleigh Ride?

On the glacier moon of Myung’s Misstep, perpetually enshrouded in ice and snowstorms, the Player Characters have been contracted to transport and guard a locked box from Out of Order, the site of the moon’s still not functioning space elevator to the water-farm town of Plankton Downs. The safest means of travel is aboard a low-bodied hovercraft fitted with a heat spike it can use to anchor itself when a severe storm strikes. The Player Characters are booked aboard the Nantucket Sleigh Ride, one of these vessels with an adequate record in terms of punctuality, safety, and comfort. If the Player Characters are expecting a thoroughly uninteresting journey, then they are going to be disappointed. Amidst all of the colonial cyborgs, Martian nuns, alien tourists, and macrame owls aboard, a body is found missing its head! Then another one! And the way they died, their heads are all mangled... Could a monster out of galactic myth be stalking the halls and cabins of the Nantucket Sleigh Ride?Announcements / January 1, 2023

If you haven’t heard, we wrote a book! And it’s out right now! If you’ve followed us over the last six plus years, you know our MO: we get deep down into the berserk array of popular and outsider media produced during the Cold War and talk about what these various artifacts—lost, forgotten, seemingly disposable—mean in the larger arenas of politics and culture, then and now. We Are the Mutants: The Battle for Hollywood from Rosemary’s Baby to Lethal Weapon takes that approach and applies it to American films released between the arrival of US combat troops in Vietnam and the end of President Ronald Reagan’s second term—probably the most discussed and beloved stretch of movies in Hollywood history.

Read more about the book at our publisher, Repeater.

We talk about the book in an interview with Joe Banks at The Quietus.

Check out Andrew Nette’s review at Pulp Curry.

Have a look at Johnny Restall’s review at Diabolique.

You can buy the book pretty much anywhere books are sold, including bookshop.org, Amazon, and Penguin Random House. If you dig it, please rate it and/or review it. We need all the word of mouth we can get. Thank you and keep an eye on the site—we’ll be back soon in some (altered) way, shape or form.

Since 2001, Reviews from R’lyeh have contributed to a series of Christmas lists at Ogrecave.com—and at RPGaction.com before that, suggesting not necessarily the best board and roleplaying games of the preceding year, but the titles from the last twelve months that you might like to receive and give. Continuing the break with tradition—in that the following is just the one list and in that for reasons beyond its control, OgreCave.com is not running its own lists—Reviews from R’lyeh would once again like present its own list. Further, as is also traditional, Reviews from R’lyeh has not devolved into the need to cast about ‘Baleful Blandishments’ to all concerned or otherwise based upon the arbitrary organisation of days. So as Reviews from R’lyeh presents its annual (Post-)Christmas Dozen, I can only hope that the following list includes one of your favourites, or even better still, includes a game that you did not have and someone was happy to hide in gaudy paper and place under that dead tree for you. If not, then this is a list of what would have been good under that tree and what you should purchase yourself to read and play in the months to come.

—oOo— Dice Men: The Origin Story of Games Workshop

Dice Men: The Origin Story of Games Workshop Frontier Scum: A Game About Wanted Outlaws Making Their Mark on a Lost Frontier

Frontier Scum: A Game About Wanted Outlaws Making Their Mark on a Lost Frontier Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England

Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England The Electrum Archive Issue #1

The Electrum Archive Issue #1 Heat: Pedal to the MetalDays of Wonder ($80/£60)From the designers of Flamme Rouge, the board game of cycling ‘Grand Tours’, Heat: Pedal to the Metal is a board game of tense car races in which drivers jockey for position, manage their car’s speed and energy, requiring careful hand management of movement cards to ensure they can keep ahead of the pack and if not that, then at least, keep up. The base game is fast and furious, with a real sense of speed as the cars career around corners and accelerate onto the straights, but expansions and advanced rules add weather, road conditions, and events, which can make even a single race more challenging, let alone a whole championship. Designed for solo play or up to six players, Heat: Pedal to the Metal can be played by the family, but the expansions will appeal to petrolheads and board gamers alike as it lets the players race like it was in the sixties!

Heat: Pedal to the MetalDays of Wonder ($80/£60)From the designers of Flamme Rouge, the board game of cycling ‘Grand Tours’, Heat: Pedal to the Metal is a board game of tense car races in which drivers jockey for position, manage their car’s speed and energy, requiring careful hand management of movement cards to ensure they can keep ahead of the pack and if not that, then at least, keep up. The base game is fast and furious, with a real sense of speed as the cars career around corners and accelerate onto the straights, but expansions and advanced rules add weather, road conditions, and events, which can make even a single race more challenging, let alone a whole championship. Designed for solo play or up to six players, Heat: Pedal to the Metal can be played by the family, but the expansions will appeal to petrolheads and board gamers alike as it lets the players race like it was in the sixties! The One Ring: Roleplaying in the World of Lord of the Rings

The One Ring: Roleplaying in the World of Lord of the Rings Everybody Wins: Four Decades of the Greatest Board Games Ever Made

Everybody Wins: Four Decades of the Greatest Board Games Ever Made Gran Meccanismo: Clockpunk Roleplaying in da Vinci’s Florence

Gran Meccanismo: Clockpunk Roleplaying in da Vinci’s Florence Bones DeepTechnical Grimoire Games ($30/£30)

Bones DeepTechnical Grimoire Games ($30/£30) Judge Dredd: The Game of Crime-Fighting in Mega-City One

Judge Dredd: The Game of Crime-Fighting in Mega-City One Slaying the Dragon: A Secret History of Dungeons & Dragons

Slaying the Dragon: A Secret History of Dungeons & Dragons Odd Jobs: RPG Micro Settings Volume I

Odd Jobs: RPG Micro Settings Volume I Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England extends the reach of the Cthulhu Mythos and Lovecraftian investigative horror into the late Georgian period, a period synonymous with the novels of Jane Austen such as Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, it is these novels which this supplement for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition draws from to create a highly stratified setting that is very much one of pride and propriety, reputation and rumour, and scandal and sobriety. Both gaming and roleplaying have visited the period before, but only in a limited fashion, for example, Jane Austen’s Matchmaker and its expansion, Jane Austen’s Matchmaker with Zombies and Good Society: A Jane Austen RPG, but for the most part have preferred to visit the earlier Georgian period of the eighteenth century or the later Victorian Era of the nineteenth century with roleplaying games such as Dark Streets and Cthulhu by Gaslight respectively. Regency Cthulhu provides everything a Keeper and her players needs to explore the period and mind both their manners and the Mythos, including an overview of the period, new Investigator Occupations, new rules for Reputation, a setting, and two scenarios, as well as appendices.

Regency Cthulhu: Dark Designs in Jane Austen’s England extends the reach of the Cthulhu Mythos and Lovecraftian investigative horror into the late Georgian period, a period synonymous with the novels of Jane Austen such as Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, it is these novels which this supplement for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition draws from to create a highly stratified setting that is very much one of pride and propriety, reputation and rumour, and scandal and sobriety. Both gaming and roleplaying have visited the period before, but only in a limited fashion, for example, Jane Austen’s Matchmaker and its expansion, Jane Austen’s Matchmaker with Zombies and Good Society: A Jane Austen RPG, but for the most part have preferred to visit the earlier Georgian period of the eighteenth century or the later Victorian Era of the nineteenth century with roleplaying games such as Dark Streets and Cthulhu by Gaslight respectively. Regency Cthulhu provides everything a Keeper and her players needs to explore the period and mind both their manners and the Mythos, including an overview of the period, new Investigator Occupations, new rules for Reputation, a setting, and two scenarios, as well as appendices. 1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

Gangbusters: 1920’s Role-Playing Adventure was published by TSR, Inc. in 1982, the same year that the publisher also released Star Frontiers. It is set during the era of Prohibition, during the twenties and early thirties, when the manufacture and sale of alcohol was banned and criminals, gangs, and the Mafia stepped up to ensure that the American public still got a ready supply of whisky and gin it wanted, so making them incredibly wealthy on both bootlegging whisky and a lot of other criminal activities. Into this age of corruption, criminality, and swaggering gangsters step local law enforcement, FBI agents, and Prohibition agents determined to stop the criminals and gangsters making money, arrest them, and send them to jail, as meanwhile the criminals and gangsters attempt to outwit the law and their rivals, and private investigators look into crimes and mysteries for their clients that law enforcement are too busy to deal with and local reporters dig deep into stories to make a big splash on the front page. In Gangbusters, the players take on the roles of Criminals, FBI Agents, Newspaper Reporters, Police Officers, Private Investigators, and Prohibition Agents, often with different objectives that oppose each other. In a sense, Gangbusters takes the players back to the explanation commonly given at the start of roleplaying games, that a roleplaying game is like playing ‘cops & robbers’ when you were a child, and actually lets the players roleplay ‘cops & robbers’.

Gangbusters: 1920’s Role-Playing Adventure was published by TSR, Inc. in 1982, the same year that the publisher also released Star Frontiers. It is set during the era of Prohibition, during the twenties and early thirties, when the manufacture and sale of alcohol was banned and criminals, gangs, and the Mafia stepped up to ensure that the American public still got a ready supply of whisky and gin it wanted, so making them incredibly wealthy on both bootlegging whisky and a lot of other criminal activities. Into this age of corruption, criminality, and swaggering gangsters step local law enforcement, FBI agents, and Prohibition agents determined to stop the criminals and gangsters making money, arrest them, and send them to jail, as meanwhile the criminals and gangsters attempt to outwit the law and their rivals, and private investigators look into crimes and mysteries for their clients that law enforcement are too busy to deal with and local reporters dig deep into stories to make a big splash on the front page. In Gangbusters, the players take on the roles of Criminals, FBI Agents, Newspaper Reporters, Police Officers, Private Investigators, and Prohibition Agents, often with different objectives that oppose each other. In a sense, Gangbusters takes the players back to the explanation commonly given at the start of roleplaying games, that a roleplaying game is like playing ‘cops & robbers’ when you were a child, and actually lets the players roleplay ‘cops & robbers’.There had, of course, been crime-related roleplaying games set during the Jazz Age of the twenties and the Desperate Decade of the thirties before, most notably the Gangster! RPG from Fantasy Games Unlimited and even TSR, Inc. had published one in the pages of Dragon magazine. This was ‘Crimefighters’, which appeared in Dragon Issue 47 (March 1981). Similar roleplaying games such as Daredevils, also from Fantasy Games Unlimited and also published in 1982, and Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes, published Blade, a division of Flying Buffalo, Inc., the following year, all touched upon the genre, but Gangbusters focused solely upon crime and law enforcement during the period. Lawrence Schick, rated Gangbusters as the ‘Top Mystery/Crime System’ roleplaying game in his 1991 Heroic Worlds: A History and Guide to Role-Playing Games.

Although Gangbusters is a historical game, and draws heavily on both the history of the period and on the films which depict that history, it does veer into the ahistorical terms of setting. Rather than the city of Chicago, which would have been the obvious choice, it provides Lakefront City as a setting. Located on the shores of Lake Michigan, this is a sort of generic version of the city, perfectly playable, but not necessarily authentic. Whilst the ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ in Appendix Three of the Gangbusters rulebook does provide full stats for Al Capone—along with innumerable notorious gangsters and mobsters and upstanding members of the law, Lakefront City even has its own version of ‘Scarface’ in the form of Al Tolino! To the younger player of Gangbusters, this might not be an issue, but for the more historically minded player, it might be. Rick Krebs, co-designer of Gangbusters, addressed this issue in response to James Maliszewski’s review of the roleplaying game, saying, “With eGG and BB eager to have a background in their childhood city (if you thought Gary’s detail on ancient weapons was exacting, so was his interest in unions and the Chicago ward system), TSR's marketing research leaned toward the original fictional approach.”

Gangbusters was first published as a boxed set—the later second edition, mislabelled as a “New 3rd Edition”, was published in 1990. (More recently, Mark Hunt has revisited Gangbusters beginning with Joe’s Diner and the Old School Renaissance-style Gangbusters 1920s Roleplaying Adventure Game B/X). Inside the box is the sixty-four-page rulebook, a sixteen-page scenario, a large, thirty-five by twenty-two-inch double-sided full-colour map, a sheet of counters, and two twenty-sided percentile dice, complete with white crayon to fill in the numbers. The scenario, ‘“Mad Dog” Johnny Drake’, includes a wraparound card cover with a ward map of Lakefront City in full colour on the front and a black and white ward map marked with major transport routes on the inside. The large map depicted Downtown Lakefront City in vibrantly coloured detail on the one side and gave a series of floorplans on the other.

Gangbusters followed the format of Star Frontiers in presenting the basic rules, standard rules, and then optional expert rules. However, Star Frontiers only got as far as providing the Basic Game Rules and the Expanded Game Rules. It would take the release of the Knight Hawks boxed supplement for it to achieve anything in the way of sophistication. In Gangbusters, that sophistication is there right from the start. The basic rules are designed to handle fistfights, gunfights, car chases and car crashes, typically with the players divided between two factions—criminal and law enforcement—and playing out robberies, raids, car chases, and re-enactments of historical incidents. This is done without the need for a Judge—as the Game Master is called in Gangbusters—and played out on the map of Downtown Lakefront City, essentially like a single character wargame. In the basic game, the Player Characters are lightly defined, but the standard rules add more detail, as does campaign play. In this, the events of a campaign are primarily player driven and plotted out from one week to the next. So, the criminal Player Character might plan and attempt to carry out the robbery of a jewellery store; a local police officer would patrol the streets and deal with any crime he comes across; the FBI agent might go under surveillance to identify a particular criminal; a local reporter decides to investigate the spate of local robberies, and so on. Where these plot lines interact is where Gangbusters comes alive, the Player Characters forming alliances or working together, or in the case of crime versus the law, against each other, the Judge adjudicating this as necessary. Certainly, this style of play would lend itself to would have been a ‘Play By Post’ method of handling the planning before the action of anything played out around the table and on the map.

Yet despite this sophistication in terms of play, the crime versus the law aspect puts player against player and that can be a problem in play. Then if a criminal Player Character is sent to jail, or even depending upon the nature of his crimes, executed—the Judge is advised to let the Player Character suffer the consequences if roleplayed unwisely—what happens then? There are rules for parole and even jury tampering, but what then? The obvious response would have been to focus campaigns on one side of the law or the other, rather than splitting them, but there is no doubting the storytelling and roleplaying potential in Gangbusters’ campaign mode. Gangbusters is problematic in three other aspects of the setting. First is ethnicity. The default in the roleplaying game is ‘Assimilated’, but several others are acknowledged as options. The second is the immorality of playing a criminal and conducting acts of criminality. The third is gender, which is not addressed in terms of what roles could be taken. Of course, Gangbusters was published in 1982 and TSR, Inc. would doubtless have wanted to avoid any controversy associated with these aspects of the roleplaying game, especially at a time when the moral panic against Dungeons & Dragons was in full swing, and given the fact that it was written for players aged twelve and up, so it is understandable that these subjects are avoided. (The irony here is that Gangbusters was seen as an acceptable roleplaying game by some because you could play law enforcement characters and it was thus morally upright, whereas despite the fact that the Player Characters were typically fighting the demons and devils in it, the fact that it had demons and devils in it, made Dungeons & Dragons an immoral, unwholesome, and unchristian game.)

In the Basic Rules for Gangbusters, a Player Character has four attributes—Muscle, Agility, Observation, and Presence, plus Luck, Hit Points, Driving, and Punching. Muscle, Agility, Observation, Luck, and Driving are all percentile values, Presence ranges between one and ten, and Punching between one and five. Punching is the amount of damage inflicted when a character punches another. To create a character, a player rolls percentile dice for Muscle, Agility, and Observation, and adjusts the result to give a result of between twenty-six and one hundred; rolls a ten-sided for Presence and adjusts it to give a result between three and ten; and rolls percentile dice and halves the result for the character’s Luck. The other factors are derived from these scores.

Jack Gallagher

Muscle 55 Agility 71 Observation 64 Presence 5 Luck 36

Hit Points 18

Driving 68 Punching 3

At this point, Jack Gallagher as a basic character is ready to play the roleplaying game’s basic rules, which cover the base mechanic—a percentile roll versus an attribute, plus modifiers, and roll under, then fistfights, including whether the combatants want to fight dirty or fight fair, gunfights, and car chases. Luck is rolled either to avoid immediate death and typically leaves the Player Character mortally wounded, or to succeed at an action not covered by the attributes. Damage consists of wounds or bruises, gunshots and weapons inflicting the former, fists the latter. If a Player Character suffers more wounds and bruises than half his Hit Points, his Muscle, Agility, Observation, and movement are penalised, and he needs to get to a doctor. The basic rules include templates for things like line of sight, rules for automatic gunfire from Thompson Submachine Guns and Browning Automatic Rifles, and so on. The rules are supported by some excellent and lengthy examples of play and prepare the player to roleplay through the scenario, ‘“Mad Dog” Johnny Drake’.

So far so basic, but Gangbusters gets into its stride with its campaign rules. These begin with adding small details to the Player Character—age, height and weight, ethnic background, rules for age and taxes (!), and character advancement. Gangbusters is not a Class and Level roleplaying game, but it is a Level roleplaying game. As a Player Character earns Experience Points, he acquires Levels, and each Level grants his player a pool of ‘X.P. to Spend’, which can be used to improve attributes, buy skills, and improve already known skills. So, for example, at Second Level, a player has 10,000 X.P., 20,000 X.P. to spend at Third Level, and so on, to spend on improvements to his character. It costs between 2,000 and 5,000 X.P. to improve attributes and 20,000 X.P. to improve Presence! New skills range in cost between 5,000 X.P. and 100,000 X.P.

Thirty-five skills are listed and detailed, ranging from Auto Theft, Fingerprinting, and Lockpicking to Jeweller, Art Forgery, and Counterfeiting. Some are exclusive to particular careers. Each skill is a percentile value whose initial value is determined in the same way as Muscle, Agility, and Observation. When a Player Character is created for the campaign, in addition to a few extra details, he also receives one skill free as long as it costs 5,000 X.P. This list includes Auto Theft, Fingerprinting, Lockpicking, Photography, Pickpocketing, Public Speaking, Shadowing, Stealth, Wiretapping.

In addition to acquiring ‘X.P. to Spend’ at each new Level, a Player Character might also acquire a new Rank. So, a Rookie Local Police Officer is likely to be promoted to a Patrolman and then a Patrolman to a Master Patrolman, but equally, could remain a Patrolman for several Levels without being promoted.

Jack Gallagher

Ethnicity: Irish American Age: 25

Height: 5’ 9” Weight: 155 lbs.

Features: Brown hair and eyes, crooked nose

Muscle 55 Agility 71 Observation 64 Presence 5 Luck 36

Hit Points 18

Driving 68 Punching 3

Skill: Auto Theft 89%

Rather than Classes, Gangbusters has Careers. These fall into four categories—Law Enforcement, Private Investigation, Newspaper Reporting, and Crime. Law Enforcement includes the Federal Bureau of Prohibition, Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.), and local city police department; Private Investigation covers Private Investigators; Newspaper Reporting the News Reporter; and Crime either Independent Criminals, Gang members, and members of Organized Crime Syndicates. In each case, Gangbusters goes into quite a lot of detail explaining what a member of each Career is allowed to do and can do. For example, the Prohibition Agent can make arrests for violations of the National Prohibition Act; can obtain warrants and conduct searches for evidence of violations of the National Prohibition Act; can destroy or confiscate any property (other than buildings or real estate) used to violate the National Prohibition Act; close down for one year any building used as a speakeasy; and can carry any type of gun. There are notes too on the organisation of the Federal Bureau of Prohibition, salaries, possibility of being corrupt, possible encounters, and notes on how to roleplay a Prohibition Agent. It does this for each of the careers, for example, how a Private Investigator picks up special cases, which are rare, and how a News Reporter gets major stories and scoops. The Crime careers covers a wide array of activities, including armed robbery, burglary, murder, bootlegging, running speakeasies, the Numbers racket, loansharking, bookmaking, corruption and more, all in fantastically playable detail. This whole section is richly researched and supports both a campaign where the Player Characters are investigating crime and one where they are committing it. Further, this wealth of detail is not just important because of the story and plot potential it suggests, but mechanically, the Player Characters will be rewarded for it. They earn Experience Points by engaging in and completing activities directly related to their Careers. Thus, a member of Law Enforcement will earn Experience Points for arresting a felon, when the felon arrested is convicted, for the recovery of stolen property, and more; the News Reporter for scooping the competition, providing information that leads to the arrest and conviction of any criminal, and so on; whilst the Criminal earns it for making money! This engagingly enforces a Player Character role with a direct reward and is nicely thematic.

Further rules cover the creation of, and interaction with, NPCs. This includes persuasion, loyalty, bribery, and the like. In fact, persuasion is not what you think, but rather the use of physical violence in an attempt to change an NPC’s reaction. There are rules too for public opinion and heat, newspaper campaigns, bank loans, and even explosives, and of course, what happens when a crook or gangster is arrested. This goes all the way up to plea bargaining and trials, jury tampering, sentences, and more. The advice for the Judge is kept short, just a few pages, but does give suggestions on how to prepare and start a campaign, and then how to make the game more fun, maintain flow of play and game balance, improvise, and encourage roleplaying. It is only two pages, but given that the rulebook for Gangbusters is just sixty-four pages, that is not too bad. In addition, there also ‘Optional Expert Rules’ for gunfights, fistfights, and car chases, which add both detail and complications. They do make combat much harder, but also much, much deadlier. Finally, the appendices provide price lists and stats for both generic NPCs and members of both the criminal classes and members of law enforcement. The former includes Bonnie Barker and Clyde Barrow, John Dillinger, and Charles Luciano, whilst for the latter, all of the Untouchables, starting with Elliot Ness, are all listed, including stats. Oddly, the appendix does not include a bibliography, which would have been useful for a historical game like Gangbusters.

The scenario, ‘“Mad Dog” Johnny Drake’, is a short, solo-style adventure that is designed to be played by four players, but without a Judge. It includes an FBI Agent and three local detectives, all pre-generated Player Characters, who are attempting to find the notorious bank robber, ‘Mad Dog’ Johnny Drake. It is intended to be played out on the poster map and sees the Player Characters staking out and investigating a local speakeasy before they get their man. The scenario is quite nicely detailed and atmospheric, but the format means that there is not much of the way of player agency. Either the players agree to a particular course of action and follow it through, or the scenario does not work. Nevertheless, it showcases the rules and there are opportunities for car chases and both shootouts and brawls along the way. If perhaps there is a downside to the inclusion of ‘“Mad Dog” Johnny Drake’, it is that there is no starting point provided in Gangbusters for the type of campaign it was meant to do.

Physically, Gangbusters: 1920’s Role-Playing Adventure feels a bit rushed and cramped in places, but then it has a lot of information it has to pack into a relatively scant few pages. The illustrations are decent and it is clear that Jim Holloway is having a lot of fun drawing in a different genre. The core rules do lack a table of contents, but does have an index, and on the back of the book is a reference table for the rules. Pleasingly, there are a lot of examples of play throughout the book which help showcase how the game is played, although not quite how multiple players and characters are supposed to be handled by the Judge. Notably, it includes a foreword from Robert Howell, the grandson of Louise Howell, one of the Untouchables. This adds a touch of authenticity to the whole affair. The maps are decently done on heavy stock paper, whilst the counters are rather bland.

–oOo–

Gangbusters: 1920’s Role-Playing Adventure was reviewed by Ken Rolston in the ‘Reviews’ department of Different Worlds Issue 29 (June 1983). He identified that, “…[T]he model of the “party of adventurers” that has been established in science fiction, fantasy, and superhero gaming is inappropriate for much of the action of Gangbusters; private detectives have always been solitary figures (who would think of the Thin Man or Sam Spade in a party of FRP characters?) and if players variously choose FBI agent, newspaper reporter, and criminal roles, it is hard to see these divergent character types will be able to cooperate in a game session. At the very least, the Gangbusters campaign will have a very different style of play from a typical FRP campaign.” before concluding, “Gangbusters is nonetheless a worthwhile purchase, if only as a model of good game design.”

–oOo–

Although mechanically simple, Gangbusters shows a surprising degree of sophistication in terms of its treatment of its subject matter and its campaign set-up, with multiple Player Character types, often not playing together directly, but simply in the same district, and often at odds with each other. However, it is not a campaign set-up that the roleplaying game fully supports or follows through on in terms of advice or help. It represents a radical change from the traditional campaign style and calls for a brave Judge to attempt to run it. This would certainly have been the case in 1982 when Gangbusters was published. The likelihood though, is that a gaming group is going to concentrate on campaigns or scenarios where there is one type of character, typically law enforcement or criminal, and these would be easier to run, but alternatively the Judge could run a more montage style of campaign where different aspects of the setting and different stories are told through different Player Characters. That though, would be an ambitious prospect for any Judge and her players.

Gangbusters: 1920’s Role-Playing Adventure is a fantastic treatment of its genre and its history, packing a wealth of information and detail into what is a relatively short rulebook and making it both accessible and readable. For a roleplaying game from 1982 and TSR, Inc. Gangbusters combines simplicity with a surprising sophistication and maturity of design.

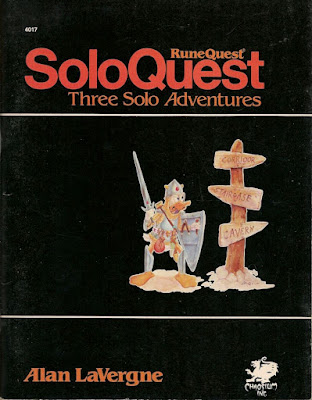

SoloQuest was published in 1982. It is an anthology of solo adventures published by Chaosium, Inc. for use with RuneQuest II, a roleplaying not really known for its solo adventures, unlike, for example, Tunnels & Trolls. However, 1982 marked the beginning of a solo adventure trend with the publication of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, the first Fighting Fantasy adventure which would introduce roleplaying and solo adventures to a wider audience outside of the hobby. SoloQuest presents three mini quests of varying complexity and storylines, but all playable in a single session or so. They are best suited to a Player Character who can fight, knows a degree of magic, and who also has a few decent non-combat skills. A Player Character with a weapon skill of 60% or more and the Healing and Protection spells, plus some Detect spells—which for RuneQuest II would have been Battle magic—will be challenged by these scenarios, but not overly challenged.

SoloQuest was published in 1982. It is an anthology of solo adventures published by Chaosium, Inc. for use with RuneQuest II, a roleplaying not really known for its solo adventures, unlike, for example, Tunnels & Trolls. However, 1982 marked the beginning of a solo adventure trend with the publication of The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, the first Fighting Fantasy adventure which would introduce roleplaying and solo adventures to a wider audience outside of the hobby. SoloQuest presents three mini quests of varying complexity and storylines, but all playable in a single session or so. They are best suited to a Player Character who can fight, knows a degree of magic, and who also has a few decent non-combat skills. A Player Character with a weapon skill of 60% or more and the Healing and Protection spells, plus some Detect spells—which for RuneQuest II would have been Battle magic—will be challenged by these scenarios, but not overly challenged.  When you die, your skeleton’s duty is ended and it hatches, leaving its fleshy, but rotting shell behind, and goes in search of both refuge and self. Some never make it. Some are buried too deep. Some are cremated. Some fall into the clutches of necromancers and some are destroyed by torch and pitchfork wielding villagers. Others though do find their consciousness and refuge, far away from the world of both Humanity and oxygen. Under the sea, on the ocean floor where they make new lives for themselves amidst the Sulphur Spires, along the Reef Roads, in the Final Shipyard, and at The Bottom of the Barrel. (It is a meeting place for undersea creatures specially constructed with an air half and a water half so that crabs, fish, wizards, witches, skeletons, and any other creatures can meet in safety.) They must deal with the mercantile Crab Cabal whose members always know what your credit rating is, Sleep Jelly (fish) that steals a Skeleton’s memories, and the oh so silent Cephalopods—so silent that they surely have to be planning something, as well as the occasional Wizard who descends into the ocean depths to continue his studies. In this strange world, the skeletons explore the ocean floor, walking, rather than swimming as they are no longer encased in the flesh which would give them buoyancy, climbing underwater mountains and ridges, absorbing the memories of those they touch to learn more about the oceanic world around them, making new memories for themselves. They are truly Bones Deep…

When you die, your skeleton’s duty is ended and it hatches, leaving its fleshy, but rotting shell behind, and goes in search of both refuge and self. Some never make it. Some are buried too deep. Some are cremated. Some fall into the clutches of necromancers and some are destroyed by torch and pitchfork wielding villagers. Others though do find their consciousness and refuge, far away from the world of both Humanity and oxygen. Under the sea, on the ocean floor where they make new lives for themselves amidst the Sulphur Spires, along the Reef Roads, in the Final Shipyard, and at The Bottom of the Barrel. (It is a meeting place for undersea creatures specially constructed with an air half and a water half so that crabs, fish, wizards, witches, skeletons, and any other creatures can meet in safety.) They must deal with the mercantile Crab Cabal whose members always know what your credit rating is, Sleep Jelly (fish) that steals a Skeleton’s memories, and the oh so silent Cephalopods—so silent that they surely have to be planning something, as well as the occasional Wizard who descends into the ocean depths to continue his studies. In this strange world, the skeletons explore the ocean floor, walking, rather than swimming as they are no longer encased in the flesh which would give them buoyancy, climbing underwater mountains and ridges, absorbing the memories of those they touch to learn more about the oceanic world around them, making new memories for themselves. They are truly Bones Deep…Lots of little things going on here during this time between 2022 and 2023. I am not sure what day it is or even the time, but hey, here we are.

Hastur, Ifrit Princess, and 3 Goblins in a trenchcoat.

Hastur, Ifrit Princess, and 3 Goblins in a trenchcoat.Year of the Monster

I have made some oblique references to this, but 2023 is going to be my Year of the Monster. Going back to my earliest roots of this hobby and talking more about monsters and monster-related topics. So more monsters for NIGHT SHIFT, more Monstrous Maleficarum, and a few other projects I have in my back pocket.

So this is one I just found out about. The idea is neat. Detail a new room every day for a 12-level mega-dungeon in 2023. I have never really been a fan of mega-dungeons, BUT as a writing exercise, I can see how it would be fun. I would want to have a theme and do it for Old-School Essentials. Though I have not made up my mind just yet.

New Year, New Character

I have done this for the past two years, and it was fun. I had an idea for this year but have run out of time to do it right. Have to think some more about this one.

OGL 1.1 and One D&D

Well. Once again, people are freaking out. Here is exactly everything we know for sure about the new OGL coming out when the next version of D&D is released.

And that is it.

Everything else is, at best, speculation and, at worst, Chicken Little style running around fear mongering. My personal plans are not changing. I will still publish under the OGL 1.0a, and still use the 3.5, Pathfinder, and 5e SRDs as I see fit.

Other Items

More "This Old Dragon" and other regular features. I am undecided on The April A to Z Challenge yet, and I am pretty sure I will not do another 100 Days of Halloween. But who knows.

Hope everyone is having a great Holiday Season.

Hope everyone had a wonderful Christmas who celebrates.

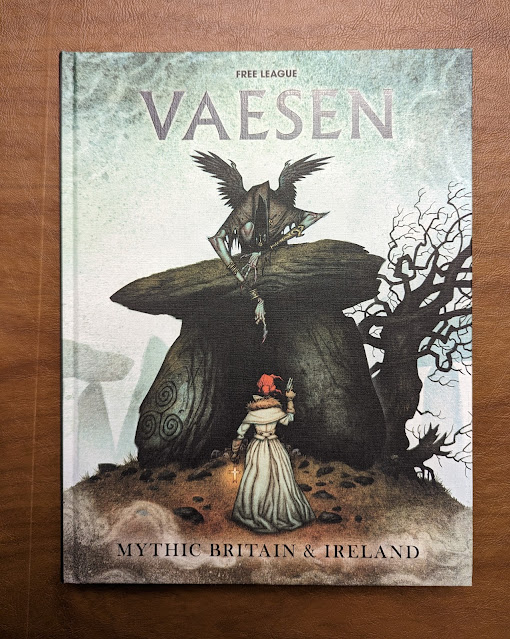

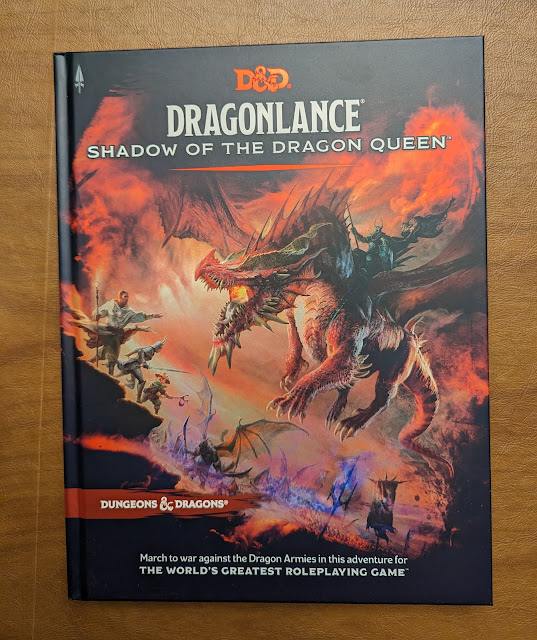

Around here, we give (and receive) a lot of geeky gifts, thought I might show off a few.

Victorian? Horror monsters? England and Ireland? Yes, please! Got this from my oldest. My youngest printed off a bunch of demons and devils for me on their 3D printers too. Expect a review for this one!

My oldest ended up with multiple copies of the new Dragonlance book. So I got this one! ;)

AND after 40 years, I finally got a copy of Steve Jackson Games' Undead!

I am planning a larger review of it, and it's counterpart from TSR, Vampyre.

Both mini-games deal with the hunt for Dracula. So looking forward to playing them both and seeing how they compare.

I should also point out one other gift.

My wife got me a new photo rig for taking all these pictures.

Still experimenting with lighting, angles, and settings. You will see all the results here. All the pictures above were taken using this. I even have a spare phone I could use as a permanent mount if I desire.

On the tail of Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another Dungeon Master and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

On the tail of Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another Dungeon Master and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry. Another popular choice of system for fanzines, is Goodman Games’ Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, such as Crawl! and Crawling Under a Broken Moon. Some of these fanzines provide fantasy support for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, but others explore other genres for use with Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game.

Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery is one such fanzine. Published by Stormlord Publishing, it takes Dungeon Crawl Classics to the Wild West and the Weird West of the 1880s. The discovery of ‘Demon ore’ in the Dakota Territory in the 187os leads to the establishment of the town of Brimstone in South Dakota, conflict with Lakota and other Plains Indians, and a rush to work the mines soon built under the town and the Dark Territories surrounding it, to strike it rich! With it came graft and corruption and Demon Stone and Hellstones. Since Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery is published as a series of fanzines, its secrets and details are revealed issue by issue rather than in one go. Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 1 introduced the setting and got a Judge and her players playing with a ‘Character Funnel’. A feature of the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, this is a scenario specifically designed for Zero Level Player Characters in which initially, a player is expected to roll up three or four Level Zero characters and have them play through a generally nasty, deadly adventure, which surviving will prove a challenge. Those that do survive receive enough Experience Points to advance to First Level and gain all of the advantages of their Class. What those Classes are, are not revealed in Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 1, but they are in Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2.

Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 was published in 2015 and picked up where Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 1 left off. It includes new rules and new Classes, changes to existing Classes, magical items, a patron, and more for running a Black Powder, Black Magic campaign under the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game. These begin with ‘Armour and Armour Class’ which removes armour from the setting, which would be useless against firearms anyway, in favour a Defensive Bonus based on Class and Level. It represents a Player Character’s combat awareness, use of cover, and simple luck when comes to being in a gun fight. It is a simple solution, more of a fudge to account for the fact that Black Powder, Black Magic is not a realistic Wild West setting, but a pulp horror Wild West setting. Alongside the new rules are a couple of pieces of magical armour, or rather magical items which provide a bonus to Armour Class. A nice touch is that they have their downsides too. For example, the Moonstone Spectacles both protect the wearer from the effects of the midday sun and grant a +2 bonus to Armour Class because they distract opponents, but they also occasionally distract the wearer and force him to attack someone other than the intended target. This combination of a benefit and a penalty makes these magical items more interesting and gives them more than the singular effect within the game.

‘Core DCC Classes in Black Powder, Black Magic’ gives the alterations necessary to make them fit the setting. For the Cleric, there is a choice of Clerical Traditions to chose from, including Protestant Preacher, Catholic Priest, Native Shaman, Chinese Mystic, and Cultist of the Old Gods . These primarily provide choice of weapons and the unholy creatures that each Clerical Tradition acts against, and they are bare bones. Enough to get started, but the Judge may want to add detail to really flesh them out. The Thief distributes points to its Thief Skills according to player choice rather than Alignment as per the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, allowing an element of specialisation. The Warrior is the least changed, being the only Class to be proficient in Buffalo Guns, Cannons, and Gatling Guns. The Wizard is the most changed since magic was but absent from the world until the discovery of Demon Ore. A Wizard in Black Powder, Black Magic requires a Patron, much like the Cleric does, and needs to know or use a True Name when casting magic. This is often the caster’s own name, which becomes woven into the effects of a spell when cast. There are some fun suggestions such as having it appear in the flames of a Fireball spell! The single spell given is True Name Ritual, which enables the caster to learn the True Name of a demon, devil, summoned creature, or even another Wizard. However, the use of the True Name in Black Powder, Black Magic is really only a narrative hook, being required to cast magic, rather then providing any mechanical benefit, that is until the True Name Ritual spell comes into play provides that benefit.

The two new Classes in Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 are the Gambler and the Prospector. Gamblers vary according to Alignment, Lawful being rare and mostly working licensed establishments, whilst Chaotic Gamblers are common, willing to take big risks for big rewards. The Class has Luck like the Halfling in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, several Thief skills, and in a nice nod to The Maverick always go first in round when drawing a concealed weapon. The Prospector is typically Lawful in Alignment, methodical and practical when extracting the difficult mineral, whilst Chaotic Prospectors often align with dark powers. The Class is used to working in cramped conditions, so can fight close in with the Warrior’s Mighty Deeds of Arms with mêlée weapons, have bonuses to skills related to mining, and with ‘A Nose for the Infernal’, can sense the presence of Demon Ore. The Prospector’s Luck modifier also applies to mining and hunting for Demon Ore, and for mêlée weapons used in mining. The Class can also spend it to negate the negative effects of Demon Ore. Both Classes are fairly lightly done, but come with detail and mechanics changes enough to make them interesting to play as well as fit the setting.

‘John Henry: Steel Drivin’ Patron’ is the only Patron given in the second issue of Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery. This article does reveal a minor secret to the setting, but primarily provides the folk legend and hero as a Patron. There is a pleasing physicality to the details of the Patron, such as channelling past exertions into the Steel Drivin’ Man Patron spell to gain bonuses to physical abilities for the caster and his allies and the Shake the Mountain Patron spell which with a stamp of the caster’s foot, knocks people and causes buildings to collapse. Unfortunately, having only the one Patron severely restricts player choice when it comes to selecting the Patron for their character, exacerbated by the fact that the Wizard Class also needs a Patron.

Rounding out Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 is the first entry in the ‘Varmits!’ series. This describes creatures suitable for the setting, and for this issue, it is the Mine Wight, an undead humanoid creature when a miner dies in the presence of Demon Ore or is killed by a Mine Wight. Quiet and cunning, the deadly claws of the Mine Wight leech Luck from a victim when struck. The description is accompanied by a table of folklore to roll on—the article actually begins with how to handle folklore and research in the game—and a basic plot hook. Overall, the monster is decent, the folklore rules useful, and the hook something for the Judge to develop.

Physically, Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 is done on pale cream paper with a fittingly buff cover. It is lightly illustrated in black and white, but the illustrations are good and the issue is also well written and overall, everything feels right about this issue. Except of course, it leaves the reader, just as it will the Judge and her players, very much wanting more. There are four issues of Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery in total as well as the Brimstone Census and Fire Insurance Atlas of 1880, so there is yet more of this setting to explore. However, the actual issues of the fanzine are limited, so are difficult to find and purchase.

Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 is a solid continuation from Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 1. The changes to the Classes make sense to fit the setting and the new Classes good too, but where the issue comes up short is in including only the single Patron. More would have been very useful. Black Powder, Black Magic: A ’Zine of Six-Guns and Sorcery Volume 2 picks up where the first issue left off and delivers more of the same entertaining flavour and feel of a ‘Weird West’ suitable for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, but both Judge and players will be left wanting more.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

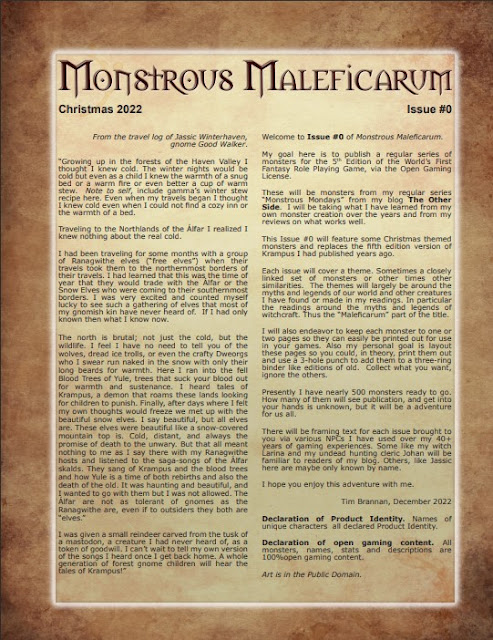

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.I am starting off my 2023 Year of the Monster this week with something I have been planning for a while.

So please allow me to announce the publication of Monstrous Maleficarum, Issue #0 Christmas Special.

From Issue #0:

My goal is to publish a regular series of monsters for the 5th Edition of the World’s First Fantasy Role Playing Game via the Open Gaming License.

These will be monsters from my regular series “Monstrous Mondays” from my blog The Other Side. I will be taking what I have learned from my own monster creation over the years and from my reviews on what works well.

This Issue #0 will feature some Christmas-themed monsters and replaces the fifth edition version of Krampus I published years ago.

Each issue will cover a theme. Sometimes a closely linked set of monsters, or other times other similarities. The themes will largely be around the myths and legends of our world and other creatures I have found or made in my readings. In particular, the readings around the myths and legends of witchcraft. Thus the “Maleficarum” part of the title.

I will also endeavor to keep each monster to one or two pages so they can easily be printed out for use in your games. Also, my personal goal is to lay out these pages so you could, in theory, print them out and use a 3-hole punch to add them to a three-ring binder like editions of old. Collect what you want, and ignore the others.

Presently I have nearly 500 monsters ready to go. How many of them will see publication and get into your hands is unknown, but it will be an adventure for us all.

There will be framing text for each issue brought to you via various NPCs I have used over my 40+ years of gaming experience. Some, like my witch Larina and my undead-hunting cleric Johan will be familiar to readers of my blog. Others, like Jassic here, are maybe only known by name.

I hope you enjoy this adventure with me.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.