Today you graduated from Meny. Today you graduated as a SLA Operative. A SLA Op. A Slop. Tomorrow you and your squad will take your first job, your first BPN or Blue Print New file, given to you by a BPN Officer at your nearest BPN Hall. You’re pretty sure it’ll be in Downtown, literally down town in the great metropolis of Mort City. It could be a Blue, and you could be exterminating a nest of rats or sewer pigs, doing a gang sweep, or breaking up some upstart soft company. It could be a White and you’ll find yourself monitoring strange activity in a neighbourhood or investigating a murder or even the activities of one of those serial killers that plague the reaches of Downtown. Or it could be Green and you’ll find yourself assigned to one of the bridgeheads out in Cannibal Sector 1, alongside the Shiver who enforce the law in Downtown, or even off planet, though being a greenhorn, that seems unlikely. Perhaps it will be Red, an emergency like a riot or a terrorist attack by DarkNight or Thresher and then you’ll get TV coverage and your chance to look good on camera, catch the eye of sponsor? Maybe. You got your BOSH SLA Blade. You got your FEN 603 Auto-Pistol. You got your ITB Mutilator Fist. You got your PP664.2 Body Blocker armour. It ain’t much, but it’s a start. You got your SLA Ops badge and Security Clearance 10. You paid your Bullet Tax. You’re ready. You’re an Operative for SLA Industries.

However, there are greater dangers which threaten Mort City, home to SLA Industries, the planet of Mort, and The World of Progress which encompasses the whole of the universe and the company’s industrial worlds, home worlds, resource worlds, labour worlds, war worlds, and more. The Grosh, the Krell, and the Momic—previously forgotten and thought lost Conflict Races from the dawn of SLA Industries’ founding, nine centuries ago—have returned from Conflict Space and begun to war against The World of Progress. SLA Industries faces a ‘Great Enemy’, said to be imprisoned on a world known as ‘White Earth’ from where twisted and bitter secret knowledge has leaked. Some of this was learned by an amateur scholar deep in Lower Downtown, the knowledge driving him to first make blood sacrifices to White Earth, and then found the Shi’An Cult dedicated to White Earth. In the decade since its founding, the Shi’An Cult is Downtown’s largest growing religion, its members dedicated to summoning horrifying monsters from White Earth, and whilst probably killing themselves in the process, sowing fear and terror amongst the downtrodden citizens of Mort. However some threats come within. In a company as large as SLA Industries, it is easy to hide corruption; the newly formed Moral Right Division sends out patrols to educate civilians on the virtues of morality, dignity, and civility, but mostly consist of bully boys out to have a good time and repress the populace; and then there is Mr. Slayer, the head of SLA Industries, an undeniably evil megacorporation and government. He has his own secrets. Who he is. Where he is from. What he knows and what he has done to ensure the growth and survival of his company. These secrets and knowing the Truth about The World of Progress? That is the ultimate danger as The World of Progress stands on the precipice of the World of Change.

This is the set-up for

SLA Industries, a roleplaying game originally published in 1993 by

Nightfall Games. Since its initial release, it has suffered a somewhat peripatetic existence, finding home with publisher after publisher, but receiving relatively light attention from each. However, the roleplaying game finally got attention it deserved in 2016 with the release of the excellent

SLA Industries: Cannibal Sector 1, before releasing

SLA Industries, Second Edition following a successful

Kickstarter campaign. With the publication of the second edition, SLA Industries has been given a major overhaul. This includes an entirely new set of mechanics, the ‘S5S’ System; an updating of the setting from its original year of 901sd to 915sd; and a makeover. Like

Cannibal Sector 1 before it,

SLA Industries, Second Edition is generously illustrated with gloriously gorgeous and gory artwork. The artwork in the first edition was good, but here, in rich, full colour, we get to see The World of Progress and its splatterpunk, noir horror dystopia like never before.

In

SLA Industries, players take the roles of Operatives for the company. A Player Character in

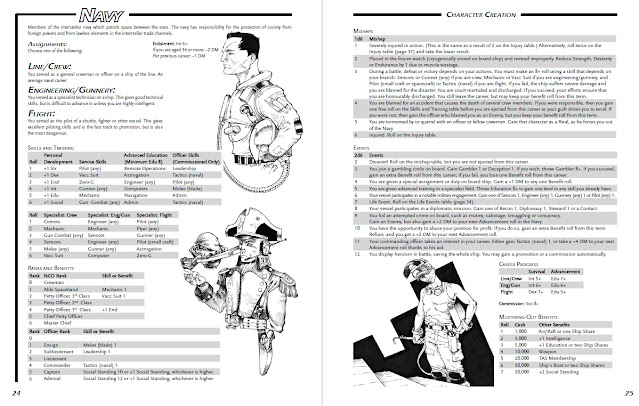

SLA Industries, Second Edition is defined by his Species, stats, Ratings Points, skills, and traits.

SLA Industries, Second Edition has nine Species. Three are Human-like. These are Humans; Frothers, drug-fuelled and tolerant who go berserk and fight with a power claymore; and Ebonites, who use the mystic power of the Ebb to alter the fabric of reality. They are divided between Ebon and Eban, who embody the positive and negative versions of the Ebb. SLA Industries also bioengineer SLA Operatives, the Stormer 313 ‘Malice’ and the Stormer 711 ‘Xeno’, designed for their speed, ferocity, and their presence in combat and thus on camera. Shaktar and Wraithen, are aliens, Shaktar being honourable warriors with fleshy dreadlocks and a prehensile tail, and Wraithen, feline and reptilian hunters known for their acute senses and response times. Advanced Carrien and Neophron are new additions to SLA Industries and thus as Operatives. Advanced Carrien or ADV Carrien are Carrien Pigs which have survived their litter and raised by SLA Industries to work as SLA Operatives because they are highly adapted to life on the polluted World of Progress. The Neophron are bird-like aliens, known for their grace, charm, and inquisitiveness, who prefer methods other than violence.

An Operative has six stats—Strength, Dexterity, Knowledge, Concentration, and Cool. The sixth is Luck, except for the Ebonite, who have the Flux stat instead. Stats are rated between zero and six, whilst the skills are rated between one and four. Ratings Points represent an Operative’s ratings in various areas, such as televised action, corporate sponsorship, or faith in his own abilities. They are expended to overcome obstacles, perform cinematic feats, or avoid certain death or defeat. They are divided between three categories—Body, Brains, and Bravado. To create an Operative, a player selects a Species, assigns twelve points to his stats, thirty points to skills, chooses traits—positive and negative, and purchases equipment beyond the standard assigned to all Operatives. Skill points also come from the Operative’s Species and choice of Training Package, which include Strike & Sweep, Close Assault, Heavy Support, Scout, Medic, Investigation & Interrogation, Technical, and Bureaucrat.

Tanktop – Stormer 313 ‘Malice’

Close Assault Operative, SCL 10

Strength 6 Dexterity 5 Knowledge 1 Concentration 1 Charisma 1 Cool 3 Luck 2

Hit Points: 28

Rating Points

Body 4 Brains 0 Bravado 2

Initiative Bonus: 6

Species Abilities: Regeneration (2), Physical Favourite

Traits: –

Skills

Strength – Climbing 2, Melee Weapons 3, Throw 1, Unarmed Combat (Brawling) 3

Dexterity – Acrobatics 2, Athletics 2, Pistol 1, Rifle 2, Stealth 2

Knowledge –

Concentration – Detect 1

Charisma –

Cool – Intimidate 3, Survival 1

Luck –

Money: 100c, 100u

Equipment – Boopa CASDIS, Finance Chip, Headset Communicator, Klippo Lighter, Operative organiser & admin kit, Pack of Contraceptives, SLA Industries ID Card, SLL Badge, Two Sets of Cloths and Boots

Armour – PP664.2 Body Blocker armour

Weapons – Stormer Chucklerduster (2), FEN 603 Auto-Pistol (4 clips), SLA Blade, SLA 10-05 Bully Boy Shotgun (4 clips)

Mechanically,

SLA Industries, Second Edition uses the ‘S5S’ System. This is a dice pool system which uses ten-sided dice. The dice pool consists of one ten-sided die, called the Success Die, and Skill Dice equal to the skill being used, plus one. The Success Die should be of a different colour from the Skill Dice. For example, if Tanktop needed to make a Stealth check, his player rolls a total of four dice—the Success Die plus two Skill Dice for Tanktop’s Stealth skill of two, plus one. The results of the dice roll are not added, but counted separately. Thus to each roll is added the value of the Skill being rolled, plus its associated stat. If the result on the Success Die is equal to or greater than the Target Number, ranging from seven and Challenging to sixteen and Insane, then the Operative has succeeded. If the results of the Skill Dice also equal or exceed the Target Number, this improves the quality of the successful skill attempt. However, if the roll on the Success Die does not equal or exceed the Target Number, the attempt fails, even if multiple rolls on the Success Dice do. Except that is where there are four or more results which equal or exceed the Target Number on the Success Dice. This is counted as a minimum success though.

Luck can also be spent to reroll dice. This is either a point to reroll the Success Die or any of the Skill Dice, but can also spend them on a one for one basis to improve the result of the Success Die.For example, Tanktop has captured Angus Ablanko, a suspected Dark Night sympathiser. He has clammed up and refuses to talk. Tanktop looks him over, gives him the once over and promises to drag him down the street and into every single fight by rope with his hands tied… “Think of it like a fight on the telly, but really, really close up.” And then he grins. Tanktop has Intimidate of three, so his player rolls the Success Die and three Skill Dice plus one, for a total of five. He will be adding a total of six—three each for the Intimidate skill and the Cool stat—to each of the dice. The Game Master has set the Target Number at Complex or ten, because Angus is showing a bit of bravado. However, Tanktop’s player rolls five on the Success Die, and then five, six, eight, and ten on the Skill Dice. This an unbelievable success, and Angus literally collapses blubbing and begging the Stormer not to drag him into any fights. Between sobs, he tells Tanktop’s squad—because he cannot even bring himself to look at the Stormer—who his contact is, where he hangs out, where he lives, and what he thinks he is planning.Combat uses the same ‘S5S’ System and is in the main relatively simple and straightforward. It can, however, be nasty, brutal, and short. The standard Target Number for combat is ten or Complex and if the attack roll is successful, that is the result of the Success Die is sufficient, any successful results on the Skill Dice either add extra damage or a specific body area being hit. If an Operative’s player rolls four or more successful Skill Dice, the Operative both inflicts extra damage and hits the target’s head. If an Operative’s or target’s Hit Points are reduced to zero, they are dead. They are at critical condition if they have six or less Hit Points left and suffer a wound if they suffer damage which reduces their Hit Points by half.

Against incoming damage or attacks, an Operative has three options—defensive manoeuvres, cover, and armour. In melee, an Operative can assign one or more levels of his skill to defence to reduce his attacker’s roll or actively and solely dodge using Acrobatic Defence to do the same. Similarly, cover makes the target harder to hit, whilst armour reduces damage taken, but at the same time, can damage the armour itself. Different ammunition types inflict different amounts of damage, but SLA Industries impose a Bullet Tax on all ammunition. This is simply because close combat looks better on television and garners higher ratings.

Operatives can look good on camera through the use of Ratings Points, which lend themselves to a cinematic style of play. Ratings Points fall into three categories—Body, Brain, and Bravado, as do their associated Feats. For example, ‘How Did You Hit That?’ and ‘Tear Right Through Them’ are Body Feats, ‘I Just read About That Yesterday!’ and ‘Lucky Guess’ are Brain Feats, and ‘Charming Smile’ and ‘Pure Grit’ are Bravado Feats. They either cost one or two Ratings Points and add a bit more colour and dynamism to what an Operative can do.

Ebonites—and some threats faced by SLA Industries—have access to the mystic power of the Ebb to alter the fabric of reality. Not quite spells, not quite psionics, the study of the Ebb is divided between ten disciplines, ranging from Awareness, Blast, and Communicate to Senses, Telekinesis, and Thermal (Blue/Red). Like skills, each discipline has four ranks, but each rank grants access to a pair of abilities. For example, at Rank 2, the discipline Reality Fold grants ‘Jump Port 2’ and ‘Shared Port’, the ability itself being akin to teleportation. Points of Flux have to be expended to use disciplines, an Ebonite calculating the formulae for each discipline via their Deathsuits, which takes concentration.

The mediatisation of violence within The World of Progress is in part represented by a lengthy list of arms and armour, and other equipment. All of which is very nicely illustrated. This adds to elements of game play as not only do the stats of a weapon or suit of armour matter, but so does their name and look. After all, they are designed to look good on television and if an Operative can get good coverage on camera, then he might gain sponsorship from a manufacturer. The equipment list also includes a lengthy list of combat drugs, one reason the roleplaying game carries a mature warning.

Rounding out

SLA Industries, Second Edition is ‘Threat Analysis’ and ‘Web of Lies’. The former presents a wide range of dangers that the Operative might face on the streets of Mort and beyond. These threats range from Carnivorous Pigs, Carrien, and things that seep in from White Earth to rival soft companies such as Dark Knight, Thresher, and Tek Trex, Dream Entities, serial killers, and the freelancer mercenaries and vigilantes known as Props. These are all decently detailed and superbly illustrated.

‘Web of Lies’ is a chapter of advice for the Game Master. It is ultimately where the problems with

SLA Industries, Second Edition come to head. What it covers is advice on running the game, in particular, the Blueprint News file types, what they entail, their importance, and what the rewards they pay out to the Operatives. Added to this are Hunter Sheets, essentially bounties on particular targets or persons of interest, which are suggested as being suitable for single sessions or one-shots. The advice also covers handling the game’s mechanics, sponsorship deals for the Operatives, what they might do on their downtime, and more.

The issue with ‘Web of Lies’ is that it suggests something more than it covers, and that feeling pervades

SLA Industries, Second Edition throughout. The focus in the roleplaying game is on beginning Player Characters and Operatives, and their taking on Blueprint News file mission after Blueprint News file mission, in order to increase their Security Clearance, climb the corporate ladder, gain sponsorship, and fame and fortune. It does a very good job of explaining what an Operative does in

SLA Industries, Second Edition and The World of Progress. From the outset, a player and his Operative knows what he is expected to do… and yet.

SLA Industries is roleplaying game and a setting which has secrets—deep secrets. These are hidden behind layers of bureaucracy and conspiracy within The World of Progress, and ultimately, playing the roleplaying game is about discovering or being exposed to them and the consequences of that happening. Yet despite the colour fiction in the pages of

SLA Industries, Second Edition hinting at those secrets and conspiracies, none of them are actually explored in its pages or supported with advice on how to include them in play. Which is exactly what a chapter entitled ‘Web of Lies’ suggests it might do, but does not. For the player who has been a fan of

SLA Industries since original publication, this is very much less of an issue, but for anyone new to the roleplaying game and its rich setting, they are going to be left mystified as to what the significance of the colour fiction is and likely wondering quite what

SLA Industries is ultimately about. This is despite the fact that

SLA Industries, Second Edition goes out of the way in places to make itself and The World of Progress accessible, especially with the guide to Operative life which clearly explains what an Operative does on a daily basis.

SLA Industries is a roleplaying game from the nineteen nineties and ultimately, it does something that is so typically nineteen nineties. It hides its meta-plot. Or rather, its backstory. As typified by the superhero roleplaying game,

Brave New World, it keeps what is really going hidden from both players and Game Master, even though Brave New World revealed some of its secrets,

SLA Industries, Second Edition does not even do that. However, this does not mean that as written,

SLA Industries, Second Edition is unplayable, as it still provides the means to explore a very dark corporate dystopia. Perhaps though, a scenario or two would have helped.

Physically,

SLA Industries, Second Edition is superbly presented. The layout is clean and tidy, and though it needs a slight edit in places, it is engagingly written with lots of colour fiction. The artwork though, is amazing, and really does a fantastic job of bringing The World of Progress and its rain sodden, polluted, and horror haunted streets (and beyond) to life like never before.

SLA Industries, Second Edition is a great update to the original nineties darkest of dark dystopian roleplaying games. The designers have revisited the setting of The World of Progress and clearly worked hard to update it, to make it more accessible, and represent it in gloriously gorgeous colour. For the most part, they have succeeded, yet so much of The World of Progress is only hinted at and left inaccessible and that can only hamper the Game Master in the long run.

The true nature and secrets of The World of Progress will have to wait for revelations in future supplements, but as an exploration of what Mr Slayer wants you to know,

SLA Industries, Second Edition is the ultimate in dark dystopian splatter punk and corporate horror roleplaying.

—oOo—

Nightfall Games

Nightfall Games is at

UK Games Expo which takes place from Friday, June 3rd to Sunday, June 5th, 2022.

What is it?

What is it?