Review: DragonQuest, First Edition (1980)

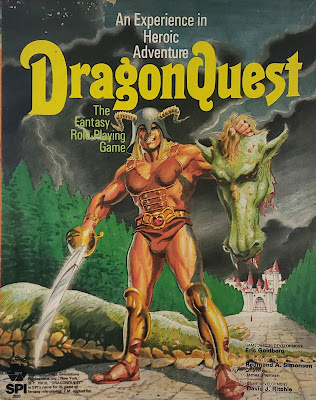

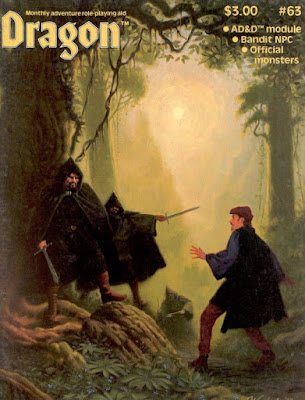

I have a history with DragonQuest. Not a complicated one or even an interesting one, but history all the same. Back in 83 or 84 or so I would head to Belobrajdic's Bookstore in my hometown every weekend. There I would get a new edition of Dragon or whatever sci-fi novel piqued my interest and then check out all the new RPG materials. One I kept going back to time and time again was DragonQuest. This was the 2nd Edition softcover and looked really different than anything I had played so far. The barbarian proudly holds the severed head of a dragon.

I have a history with DragonQuest. Not a complicated one or even an interesting one, but history all the same. Back in 83 or 84 or so I would head to Belobrajdic's Bookstore in my hometown every weekend. There I would get a new edition of Dragon or whatever sci-fi novel piqued my interest and then check out all the new RPG materials. One I kept going back to time and time again was DragonQuest. This was the 2nd Edition softcover and looked really different than anything I had played so far. The barbarian proudly holds the severed head of a dragon. The game intrigued me so much. I flipped through it many times and even it got to the point that I annoyed the owner, Paula Belobrajdic, that she told me I should buy it. In retrospect, I wish I had. Though had I I likely would not have picked up the great-looking first edition boxed set next to me now.

My history with the first edition is not as long or as storied. I bought it a while back and it has sat on my shelves for a bit. I did do a character write-up last year, Phygor, for DragonQuest and I really liked how the character came it.

For this month of D&D, I figure a look into the game that tempted me so much would be neat to look into.

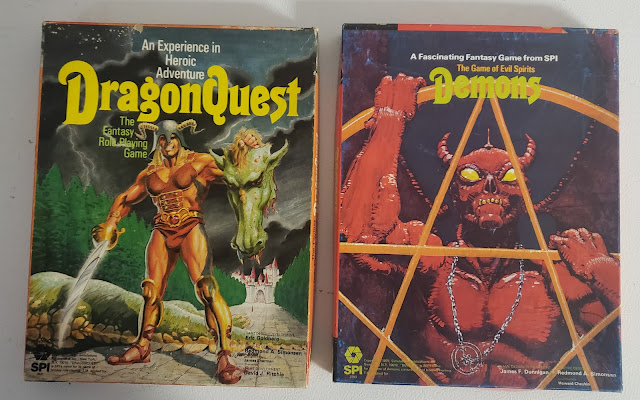

DragonQuest, First Edition (1980)

This game was published by SPI in 1980. SPI had been a wargame publisher and decided to get into the RPG market. I am sure they were seeing their market share being eaten away by RPGs, and D&D in particular. This is important since this game does feel very wargamey. This includes how the rules are presented and even how combat is run. While D&D/AD&D at this time was open to minis and terrain maps this game requires them. Or at least chits and the included maps.

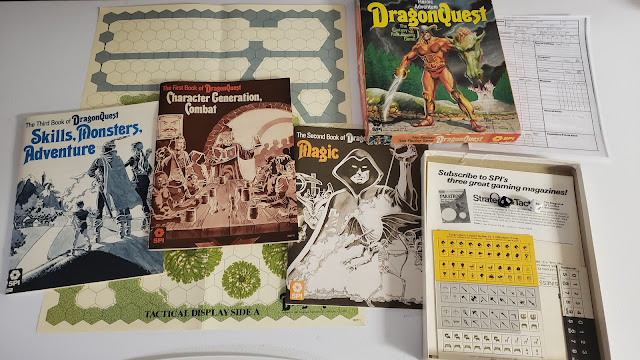

The boxed set I have contains three soft-cover books. Some chits. Some ads, a comment card, and a tactical hex map. My set does not have dice, but I also don't think it originally came with dice. I added two d10s myself.

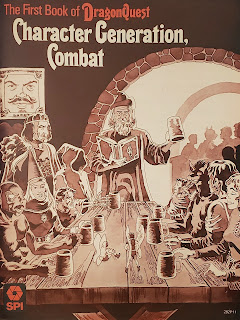

The First Book of DragonQuest: Character Generation, Combat

The First Book of DragonQuest: Character Generation, CombatOur first book is the smaller of the three at 32 pages. The format is three-column and the rules are all presented in "wargame" style. So Adventure Rationale can be coded as II.1.A.1. I won't be using this much but it does make it easy to find any rule. A little cumbersome at first and then it gets really easy.

This was an interesting time. The Introduction (I.) and How to Play the Game (II.) don't spend a lot of time with the "This is a Roleplaying Game" and instead gets down to business. Requirements for play are discussed as well as Game Terms (III.).

We get into Character Generation (IV.) This is not a completely random affair as D&D was at the time. You roll and get a pool of points. Though with a high number of points, your maximum is low, likewise a small amount in a point pool will give you a higher maximum. The traits are Physical Strength, Agility, Magical Aptitude, Manual Dexterity, Endurance, Willpower, and Appearance. Scores are 5 to 25 for the human range. So you roll a 4d5 (1d10/2) which will generate a score from 4 to 20. Compare this to the table under 5.1. This table gives you your point pool (82 to 98) and a Group (A to G) These groups refer to the maximums. A = 25, B = 24 and G =19.-

There are even some rules for developing other types of abilities if the Game Master desires them. After this other details are figured out; Gender (or even genderless), handiness, human or non-human (such as Dwarf, Efl, Giant, Halfling, Orc or Shape-changer), various Aspects, and Heritages. It can be a complex character system all for what is nominally an 18-year-old. This all covers the first dozen pages. There are no classes (rather famously so) and more to your character from the next books.

The last half+ of this book covers combat. All movement and combat is done on a hex grid, not a square one. Gives it an interesting twist and again a holdover of their wargame roots. Plenty of diagrams and examples are given. Combat rounds are 10 seconds and can be made up of an undefined increment of time called a Pulse. There are Strike Zones, Fire Zones, and all sorts of fun bits. I am reminded of combat in D&D 3rd Edition here to be honest.

Damage is an equally detailed affair with damage affecting Fatigue and Endurance. When Fatigue is 0 damage starts happening to Endurance, there is a similar idea here in D&D 4th edition. Maybe when TSR bought SPI DragonQuest didn't entirely disappear. There is also Grievous injury which is much worse.

Personally, I feel any D&D player could get a lot out of reading this combat section, at least give it a play-through once.

The Second Book of DragonQuest: Magic

The Second Book of DragonQuest: MagicAsk anyone that has ever played both DragonQuest and D&D about what sets the two games apart the most and you are likely to hear "Magic." In 1980 DragonQuest took an approach to magic that would not be seen in other games until much later. What made it different then? Three pretty good reasons. Mana, different kinds of spells, and Colleges.

Mana in DragonQuest fuels the magic an Adept can use. Spell casting can be tiring and there is never a guarantee that the spell will work. It could fail or backfire. Even when it works the target can be resistant to it. And Adepts can never wear metal to top it all off. This notion is pretty commonplace now, but then it was new and exciting. I have lost track of how many "spell points" and "mana" systems I have seen applied to AD&D over the years and that is not counting systems like Mage and WitchCraft that use some form of Essence or Quintessence. Ass expected Magical Aptitude is important here, but so is Willpower and even Endurance.

The different sorts of spells the adept has access to. Nearly every adept has access to at least one magical talent (I'll get to that). These talents can be thought of as a power that can always be used and they are related to the Adept's college. Then there are "normal" spells. These are the most "D&D" like and each college has its own lists and there is very little crossover, though each college has something going for it. The limiting factors here are how many spells you know. Finally, there are rituals. These are like spells that take longer, usually much longer, require more components but have a far better chance of success.

I have talked a bit about them already, but DragonQuest's adepts learn their magic from distinct Colleges. There are twelve colleges: Ensorcelments & Enchantments, Sorceries of the Mind, Illusions, Naming Incantations, Earth Magics, Air Magics, Fire Magics, Water Magics, Celestial Magics, Black Magics, Necromancy, and Greater Summonings. Each college has its own requirements. After the college descriptions, we get [xx.1] restrictions, [xx.2] modifiers, [xx.3] Talents, [xx.4] Spells, [xx.6] General Rituals and [xx.7] Special Rituals. There are 30 pages of these.

This should all sound familiar. AD&D 2nd adopted the college idea in their schools of magic; though there is more overlap in spells. D&D 4th Ed gave us at-will, encounter, and daily spells that mimic this setup. All have been recombined one way or the other in 5th Edition. Again, this was all brand new in 1980.

Also, something that flies in the face of all things of the 1980s is the last 25 pages. Here we get a listing of demons straight out of the Ars Goetia of The Lesser Key of Solomon. Who they are and how to summon them. And the Christians were going after D&D.

The Third Book of DragonQuest: Skills, Monsters, Adventure

The Third Book of DragonQuest: Skills, Monsters, AdventureOvertly the Game Master's book.

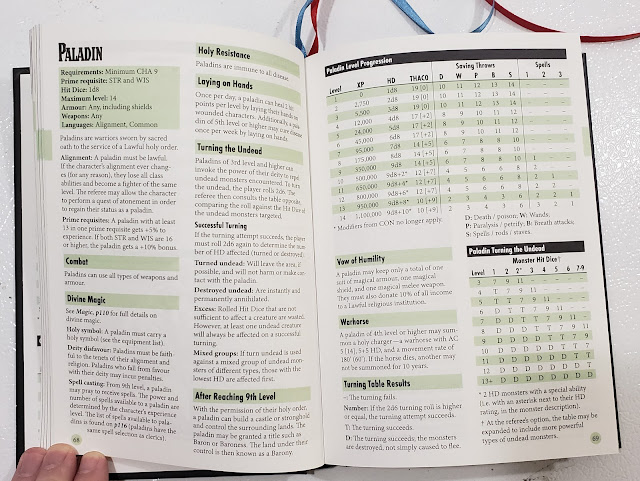

Skills can be roughly thought of as professions or even, dare I say it, classes. You get professional skills like Alchemist, Assassin, Astrology, Beast Master, Courtesan, Healer, Mechanician, Merchant, Military Scientist, Navigator, Ranger, Spy, Thief, and Troubador. Each one is covered in detail along with what each profession allows the character to do.

Each "profession" skill gets a listing [xx.1] to [xx.9] that covers what is needed to learn each skill (prereqs), what it does, and how it does it. For example, according to 53.1, a Beast Master must have a Willpower of at least 15. In 54.1 we learn that while Courtesans do not have minimum scores there is an XP penalty if they don't meet certain requirements (Dexterity, Agility, Physical Beauty) and a bonus if they have higher scores. The back cover of this book gives the XP expenditure to go up a rank in each.

Personally. I think this should have been part of the Characters' book.

The next section is all about Monsters. They are divided by like types. So all the primates, apes and pre-humans are in one section, cats in another, birds and avians, land mammals, aquatics and so on all get their own sections. Dragons get their own section, naturally, but wyverns are part of reptiles. The usual suspects are all here, but not much more than that. There are however enough points of comparison that converting an AD&D monster to DragonQuest would be easy enough. There are some differences too. Nymphs have the lower half of a goat, like that of a satyr. Gnolls are dog-faced. Kobolds look like tiny old men, neither dog nor lizard-like, and tend towards good. Medusa and Gorgons are the same creatures. Not much in the way of "new" monsters, even for 1980.

The last section covers Adventure. For a game that has such tactical wargame DNA, I expected a little more here, but I guess I am not surprised, to be honest. We also get a few tables.

--

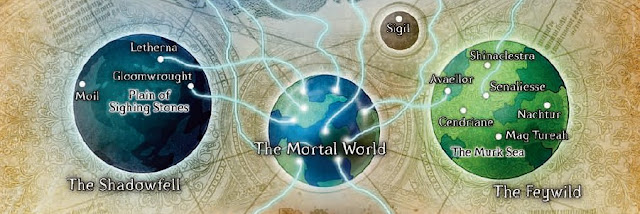

There is so much packed into this box. I can really see why this game, more than 40 years later, still has such a following. While I lament that TSR (and by extension Wizards of the Coast and Hasbro) have let this IP fall into disuse, I do see where bits of it live on in nearly all the post-1990 (AD&D 2nd ed Ed in 1989 too) versions of D&D. Schools of magic, tactical battle movement, mini use, all of these became standard. I can't say that all of these directly came from DragonQuest, but they are certainly all headed in the directions that DragonQuest started.

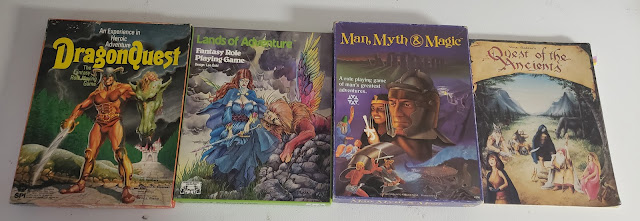

My issue right now is not counting D&D and its various forms, editions, and offsprings, I have a lot of Fantasy RPGs. Many of my favorites are more or less dead.

They are all great fun but with DragonQuest I am right where I was back in 1984; It's a great-looking game, but no one around me is playing it. If I Am going to play like it was 1984 I am going to pull AD&D 1st Ed off my shelf.

The obvious reason to choose one over the other is how well does it play? Well, DragonQuest is above and beyond many of the others in terms of rules and playability. Also as I mentioned there is a huge amount of online support, informal as it is.

There is also the idea that with DragonQuest, and adding in SPI's Demons, I could create a fun demon summoning game. But again I have to ask, can't I do this with D&D now?

Maybe DemonQuest is a game I could try out!

What are your thoughts and memories about this game?

.png)

.png)