Feed aggregator

Character Creation Challenge: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

My week of doing the characters from Dracula has been an absolute blast. Can't wait to go reread the novel again. It got me thinking about others from this time period that might work out well and there are dozens. More than I will do for this challenge for sure, but enough to keep my busy.

One such character is Dr. Henry Jekyll and his evil counterpart Mr. Edward Hyde.

This also gives me a chance to try out something different with the new Lycanthrope rules.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Dr. Henry Jekyll/Mr. Edward Hyde

4th level Inventor (Supernatural, Lycanthrope)Archetype: Disturbed Scientist/Human madman

Strength: 13 (+1) [16 (+2) p]

Dexterity: 11 (0) S [14 (0) s]

Constitution: 11 (0) [11 (0) s]

Intelligence: 16 (+2) P [16 (+2)]Wisdom: 12 (0) S [12 (0)]Charisma: 15 (+2) [15 (+2)]

HP: 18

Alignment: Light/Dark

AC: 9 [7]

Attack: +2

Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+2/+0Melee bonus: +1 [+2] Ranged bonus: 0Saves: +3 to Inteligence and Wisdom savesPowers (Jekyll): Danger Sense, Stressful Transformation, Gadgets (Hyde serum, delivery system, antiserum).

Powers (Hyde): Danger Sense, Regenerate 1d6 hp, Natural Weapons, Rip and Tear, +3 to wisdom saves.Feed: Must commit an act of violence every night.

Skills:Medicine, Science, Knowledge (Chemistry), Research

Madness: On a roll of 1 or 2 on a d6 Jekyll will transform into Hyde.--

I opted to make Dr. Jekyll an Inventor rather than a sage because that seems to work out the best. His inventions are his serum and the means to deliver it. There was a great scene in the otherwise forgettable Edge of Sanity (1989) starring Anthony Perkins as both Jekyll and Hyde. Basically, Hyde is walking around London, killing prostitutes and hitting on, for all purposes, a crack pipe. The movie was not good, but Perkins was and the scene stuck with me.

Also the Jekyll/Hyde transformation can be used as a special type of Lycanthrope, or more generally, a "science" based Therianthrope. This would be the same thing we would use for the Hulk and Cú Chulainn.

There are some more tweaks I can do to this character, but this is a good place to start.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Miskatonic Monday #92: The Catcott Collection

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

Name: The Catcott CollectionPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: The Catcott CollectionPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.Author: Peter Willington

Setting: Jazz Age Bristol, United Kingdom

Product: Scenario

What You Get: Fifteen page, 1.96 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: “Mirrors don’t lie. They only show a part of truth.”Plot Hook: Getting lost in your studies may cost you more than your Sanity...Plot Support: Detailed plot, staging advice for the Keeper, one floorplan, two handouts, and one NPC (sort of).Production Values: Excellent.

Pros# One-to-one format more engaging# Good staging advice for the Keeper

# Short, one-session, one-to-one scenario# Strong sense of personal horror# Strong sense of isolation# Nicely done feel of decay and dream-like uncertainty# Would work as an introduction for any Academic Investigator# Easy to adjust to Cthulhu by Gaslight or Cthulhu Now

Cons

# Requires a slight edit# Tome at the heart of the scenario not written up# One-to-one format more demanding than traditional scenario# Pre-generated Investigator not given as an Investigator sheet# The intimacy of the personal horror may not suit all players

Conclusion

# Isolated, intimate horror one-shot# Nicely done feel of decay and dream-like uncertainty# Demanding horror scenario for both player and Keeper

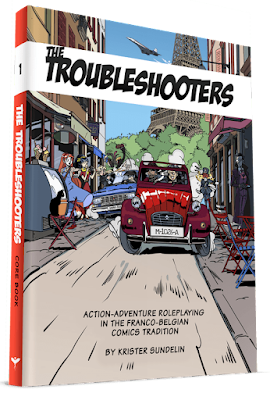

Jet Age Action

The year is 1965. On March 19th, 1964, a joint Japanese-French mission landed on the Moon aboard the giant atomic rocket Kaguyahime, the Moon Princess – affectionately called Monsieur Renard (‘Mister Fox’) in France because of its orange-red paint job. Two space stations orbit the Earth—the US Aurora and the Soviet Budushcheye-1. In the skies over Europe and far-flung cities, the Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde carries passengers at the speed of sound with BOAC, Air France, and Air Majestique. Around the world the Cold War continues between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, with Europe divided by the ‘Iron Curtain’. This includes Arenwald, the alpine principality formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, squeezed in between Hungary, Sylveria, and Yugoslavia, famous as a stop on the Arlberg Orient Express line from London to Athens, and its Soviet counterpart, the Socialist Republic of Sylveria. The Cold War is not the only threat to the world, a secret organisation known as the Octopus, a centuries-old criminal organisation, has designs on world domination. There are other dangers too, as well as mysteries and conspiracies, many of which the authorities are not best-placed to deal with. Step forward the Troubleshooters, bands of friends and adventurers who are prepared to travel the world and investigate the mysteries, crimes, and dangers that the authorities decline to do. And if they can have fun along the way, all the better!

The year is 1965. On March 19th, 1964, a joint Japanese-French mission landed on the Moon aboard the giant atomic rocket Kaguyahime, the Moon Princess – affectionately called Monsieur Renard (‘Mister Fox’) in France because of its orange-red paint job. Two space stations orbit the Earth—the US Aurora and the Soviet Budushcheye-1. In the skies over Europe and far-flung cities, the Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde carries passengers at the speed of sound with BOAC, Air France, and Air Majestique. Around the world the Cold War continues between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, with Europe divided by the ‘Iron Curtain’. This includes Arenwald, the alpine principality formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, squeezed in between Hungary, Sylveria, and Yugoslavia, famous as a stop on the Arlberg Orient Express line from London to Athens, and its Soviet counterpart, the Socialist Republic of Sylveria. The Cold War is not the only threat to the world, a secret organisation known as the Octopus, a centuries-old criminal organisation, has designs on world domination. There are other dangers too, as well as mysteries and conspiracies, many of which the authorities are not best-placed to deal with. Step forward the Troubleshooters, bands of friends and adventurers who are prepared to travel the world and investigate the mysteries, crimes, and dangers that the authorities decline to do. And if they can have fun along the way, all the better!This is the set-up for The Troubleshooters: An Action-Adventure Roleplaying Game inspired by French and Belgian comics—bande dessinée or bédé—such as Tintin, Spirou et Fantasio, Blake & Mortimer, and Yoko Tsuno. Published by Helmgast following a successful Kickstarter campaign, this is an action-adventure roleplaying game set in the second half of the sixties and first half of the seventies, an era of glamour, optimism, and technological advances. Its outlook is optimistic and exciting, a metropolitan world primarily set across a Europe full of diverse and exotic locations. The players will take the roles of the Troubleshooters, freelance adventurers and investigators, friends ready to look into mysteries and crimes, travel to exotic locales, and have adventures! The Troubleshooters can have a theme and thus be a band of curious adventurers, sleuths, agents, or criminals (in the tone of ‘gentleman thieves’)—and The Troubleshooters starts off by discussing these and giving sample inspirations. Each Troubleshooter should be competent, have a particular role in the group—such as the Doer, Investigator, or Muscle, want to adventure, possess a weakness which enhances the story, be fun to play, and fun to play with.

A character in The Troubleshooters is defined by Skills, Max Vitality, Plot Hooks, Traits, Abilities, Complications, and Story Points. Skills—rated as percentiles—are broken down into Background, Social, Investigation, Action, and Combat skills, and they include skills such as Agility, Endurance, Strength, and Willpower, which in other roleplaying games would be used as attributes. Plot Hooks, such as ‘Do-Gooder’ or ‘Media Darling’, are used to pull Troubleshooters into a scenario, and published scenarios will use specific Plot Hooks to involve Troubleshooters. Abilities mark the Troubleshooter out as a special and come in three Tiers with increasingly harder requirements, but at each Tier provide a means for the Troubleshooter to spend Story Points. For example, the Actor Ability requires the Entertainment skill at 65%, and when used with other skills like Charm or Subterfuge, enables a Troubleshooter pretend to be another person. For one Story Point, the Troubleshooter can flip a Subterfuge task check when pretending to be someone else, but for two, he can make a new task check for Entertainment or Charm, and keep the new roll. Complications are roleplaying hooks, for both the player and the Director of Operations—as the Game Master is known in The Troubleshooters is known—and also a source of Story Points. For example, a Troubleshooter with the ‘Amorous’ Complication will earn three Story Points when distracted by his emotions and receives a −2 pips modification to task checks not related to said emotions, three Story Points if a romantic interlude causes him trouble, and six Story Points when a date or romantic interlude prevents him from participating in an important scene.

Troubleshooter creation is template based, though guidelines are included which allow a new template to be built or a Troubleshooter to be built without using a template. Fifteen templates are included from Adventurous Scholar, Aspiring Student, and Caring Veterinarian to Racing Driver, Suffering Artist, and Vigilante Lawyer. Each template includes some background, eleven skills, five Abilities, three Complications, Vitality, extra languages, three gear kits, and some Plot Hook suggestions. A player can modify the skills, but must choose two Abilities, one Complication, five gear kits (this is three more than the template gives, but there is an extensive list of gear included in the book), and two Plot Hooks. He also chooses languages if his Troubleshooter has any and finally decide—or roll—where he met the other Troubleshooters. (Alternatively, the players could just use the six signature Troubleshooters included as examples who figure in all of the examples through the book.)

Dickie Jones – Curious Engineer

Skills: Contacts 45%, Electronics 65%, Engineering 75%, Investigation 45%, Machinery 65%, Science 65%, Search 65%, Security 45%, Melee 45%, Vehicles 45%, Willpower 45%. (All other Skills 15%.)

Abilities: Curious, Tech Wiz

Complications: Combat Paralysis, Crude

Vitality: 5

Languages: –

Gear: Camping Gear, Ham radio set, Electronics toolbox, First Aid Kit, Mechanic’s toolbox (Signature)

Plot Hooks: Friends in High Places, I Owe You

Mechanically, The Troubleshooters is a percentile system. To undertake a Task, a Troubleshooter’s player rolls percentile dice and if the result is equal to or less than the skill and the Troubleshooter succeeds. If the roll is a double and below the Skill value, then the Troubleshooter earns Good Karma, succeeding with a bonus and gains a Story Point. Conversely, Bad Karma is gained if a double is rolled and it is above the Skill value. The Karma can be mechanical or storytelling in nature. The former might be +2 or -2 Pips for Good or Bad Karma, the latter reinforcements turn up, either to help or hinder the Troubleshooters, depending upon whether it is Good or Bad Karma. Modifiers to the roll come in the form of Pips, which range from +5 to -5. If the number of Pips is positive, then any result equal to, or less than the number of Pips on the Ones die will always succeed, even if the actual percentile roll is greater than the Skill value. Conversely, if the number of Pips is negative, then any result equal to, or less than the number of Pips on the Ones die will always fail, even if the actual percentile roll is less than the Skill value. Pips can be applied because the environment, such as in the middle of a storm, or equipment used, such as a tool kit. The Pips system does feel a little weird, even counterintuitive, but it does not take much adjusting to, and once you have, it is very workable.

Notably, if a test is failed, it cannot be repeated, either by the current Troubleshooter or any other Troubleshooter—unless circumstances have changed significantly. Failure though is not intended be an absolute, but rather that the Troubleshooter ‘Fail Forward’ and either learn from the failure or push the story on in interesting ways. For example, in a fight, a Troubleshooter might not be killed, but rather captured, or if a Troubleshooter fails to defuse a bomb in time, he at least learns something about the design. In addition, every Troubleshooter has Story Points. Their most common use is to flip the results of a percentile roll. However, they can also be spent to activate Abilities, get gadgets beyond the standard five a Troubleshooter starts play with, gain clues, and either add something major or minor to the ongoing story. Adding something to the story may require a little negotiation with the Director.

For example, Dickie Jones is participating in a rally across Sylveria. He is the co-driver in a car driven by his fellow Troubleshooter, Tristan Narbrough, but in addition to wanting to place well in the event, they are after a Soviet spy who is heading for the Socialist Republic of Sylveria with some information stolen from one of the sponsors of their car. However, during a night stage, in the middle of a storm, their car, a Mini-Cooper breaks down. Dickie leaps out of his seat, tool kit in hand, and pulls up the bonnet. To determine the fault and fix is going to require a Machinery 65% Test. The Director of Operations sets the Task at ‘-2 Pips’ for the storm, but Tristan’s player describes how he is holding a torch to make sure that Dickie can see what he is doing, which negates the ‘-2 Pips’. Plus, of course, Dickie has his signature Mechanic’s toolbox, which gives him two Pips. So, Dickie’s player is rolling his Machinery 65% Skill at ‘+2 Pips’. Dickie’s player rolls 99%! Not only is this a failure, but it is also one with Bad Karma. This could be bad news for both Dickie and Tristian, but Dickie has the Tech Wiz Ability, which enables his player to reroll an Electronics, Engineering, or Machinery Task for one Story Point. Dickie’s player spends the Story Point and rerolls, but the result is a 71%--better but still a failure… Except no, the value on the Ones die is less than the Pips, which means that Dickie finds the fault, fixes it, and they are back on the road again, driving hard to catch up with and capture the industrial spy!

Combat in The Troubleshooters is more complex and is built around opposed Tests between attacking and defensive Skills, for example, Melee versus Melee Skill or Ranged Combat versus the Agility Skill. The Troubleshooters, as Player Characters, have Defence Skills, but unless they are important, Director characters (or NPCs) do not. Initiative is handled with an Agility Test, with the rests of the two dice added together if successful. Damage is rolled on six-sided dice, typically just two for unarmed attacks, all the way up to seven for machine guns. Rolls of four, five, and six inflict a point of Vitality damage per die, with results of six exploding and potentially doing more damage. Armour allows Soak rolls which negate points of damage, but do not explode. Recovery rolls, made to recover Vitality work the same as Soak rolls. A Troubleshooter or an important Director character is out Cold when they run out of Vitality, although either can take the Wounded or the Mortal Peril Condition instead of suffering Vitality loss. This typically to void being Out Cold, but both have consequences after the fight and take time to heal. What is stressed throughout The Troubleshooters is that it is not a roleplaying game about killing and that it is very difficult for a Troubleshooter to die. Indeed, the most common way of a Troubleshooter dying is when it is dramatically appropriate and the Director has stated that it is a possibility in a scene. As to killing, if a player has his Troubleshooter kill a Director character in cold blood, then the Director is advised to deny the Troubleshooter any free improvement checks at the end of the adventure, and remove all of the Troubleshooter’s Story Points, as well as half of the Story Points of those Troubleshooters’ who could have stopped him. This is harsh, but The Troubleshooters is intended as a positive roleplaying and roleplaying experience.

For the Director of Operations, there is good advice on setting up combat scenes to make them interesting and challenging, adjudicating the use and awarding of Story Points, an extensive list of Gear—including Weird Tech with which to equip the bad guys or interest any budding Tech Wiz Troubleshooter. The advice also covers hosting and running the game, portraying the Director’s characters—including how to make the bigger villains camp, and creating adventures and campaign. She is accorded a full description of the Octopus, its organisation, members, aims, and technology, plus plenty of stats and write-ups of various Director characters and animals. In terms of background, ‘The World of The Troubleshooters’ presents the period and setting in some detail, highlighting not just the differences between the sixties that we know from history and the sixties of The Troubleshooters, but also the similarities. It covers technology, travel, and more before providing a whirlwind guide to some of the interesting places and cities around the world, from Paris and Berlin to Buenos Aries to Ice Station X-14. These are really good, describing each location in a couple of pages including lists of where to stay, things to do, and why that location is being visited as part of the Troubleshooters’ adventure. In fact, these location descriptions feel reminiscent of the Thrilling Locations supplement for the James Bond 007 roleplaying game from 1983 and certainly that sourcebook could be useful until The Troubleshooters gets one of its own. Rounding out The Troubleshooters is a set of appendices which include a calendar for 1965, lists of first names in various languages, a table of character traits, and several lists of profanities, but not profanities, which should allow a Troubleshooter to swear, but not swear, and still maintain the spirit of the bande dessinée. “Blue blistering barnacles!” indeed.

Physically, The Troubleshooters is a stunning looking book. The artwork, done in the ‘Ligne claire’ style pioneered by Hergé, nicely sets the signature cast of The Troubleshooters against the well-drawn backdrop of the real world. Make no mistake, the artwork is excellent throughout, really capturing the feel of the roleplaying’s inspiration. Although it needs a slight edit in places, The Troubleshooters is well written and an engaging read from start to finish. Throughout, the rules and situations are explained in numerous examples of play, all using the signature cast of The Troubleshooters and narrated by Graf Albrecht Vogelin Erwin von Zadrith, the Number Two of the Octopus, as the Director. These are all entertaining to read and tell a story as much as they inform about the rules.

If there are any issues with The Troubleshooters, then there are two. First, there is no scenario. Second, the other thing is that although it references various bande dessinée, it does not list actual titles. Fortunately, there are three scenarios available for the roleplaying game in The Troubleshooters’ Archive. The lack of a bibliography can be got around using the pointers included here as a starting point. In addition, The U-boat Mystery scenario is already available.

The obvious thing about The Troubleshooters is that could be used to run a James Bond style roleplaying game. It could be, and it would work well as a James Bond roleplaying game, but The Troubleshooters is not as cynical in tone or even as murderous as the world of James Bond is in comparison. Much lighter in tone, The Troubleshooters is of course a roleplaying game of adventure tourism in the style of bande dessinée, but also that of the ITC Entertainment television series of the period. For example, The Saint, The Persuaders!, and The Protectors, and whilst it is specific in its bande dessinée inspiration, The Troubleshooters is really the first roleplaying game to look back to the period since Agents of S.W.I.N.G..

The Troubleshooters: An Action-Adventure Roleplaying Game is great looking book with artwork which wonderfully evokes its source material. The rules and mechanics support play in the style of that source material, enabling the players to create fun Troubleshooters, and jet or drive off on amazing, exciting adventures with each other and tell great stories. With its comic book or bande dessinée sensibilities, there can be no doubt that The Troubleshooters takes us back to a simpler, if headier and more optimistic time. The combination means The Troubleshooters is engagingly, delightfully European and charmingly chic.

Character Creation Challenge: Quincey P. Morris

Quincey Morris is the odd man out here in the Dracula tale. He is a rich American, friends with Holmwood and Seward, and like Van Helsing he has had dealings with blood-suckers, in this case, vampire bats, before. He is also the character that gets left out of most other media more times than not.

It is Quincey, or rather his Bowie knife, that is instrumental in bringing down Dracula so Harker and Holmwood can kill him.

Had he survived the attack by Dracula he would have been a great character to become a vampire hunter. Other authors have picked up this challenge and have told stories of a survived Quincey, a vampire Quincey and even Quincey's younger brother (called "Cole" in at least one story). Quincey lives on in John and Mina's son, Quincy Harker.

Again, one of the best portrayals was Billy Campbell in Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992) which was also one of the most book accurate portrayals. Another good one is Ethan Chandler in Penny Dreadful

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Quincey P. Morris

Quincey P. Morris4th level Veteran

Archetype: Rich Texan

Strength: 13 (+1) S

Dexterity: 17 (+2) P

Constitution: 16 (+2) S

Intelligence: 11 (0)

Wisdom: 13 (0)

Charisma: 15 (+2)

HP: 24

Alignment: Chaotic Good

AC: 8

Attack: +2

Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+2/+0Melee bonus: +1 Ranged bonus: +2Saves: +2 to all saves.Powers: Combat Expertise, Improved damage, improved defense, Supernatural Attack, tracking

Skills:** Beast Whisperer, Steady Hands, Notice, Wilderness Survival

** Skills are optional in NIGHT SHIFT, but for Seward, Holmwood, and Morris I feel they are what set the characters apart and above and beyond their class abilities.

--

You can see why Arthur and Quincey are often combined in movies where they work better in a book. Here their stats are not very different, they are both even 4th level Veterans. I did that on purpose to show that with the optional skills rules you can provide more customization with the characters. They are also played quite differently.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Mavens of Murder

The mystery—as opposed to the mysterious, which has always been there—has long been a part of roleplaying, all the way back to The Maltese Clue, the scenario published by Judges Guild in 1979. It really came to the fore with roleplaying games like Call of Cthulhu, Gangbusters, and Justice, Inc. and more recently seen in the GUMSHOE System with roleplaying games such as Mutant City Blues, which combines superheroes with the police procedural. What these all do with the mystery is provide the Game Matron with a plot and a set of clues that the players and their characters investigate the mystery and hopefully piece together the clues to uncover the mystery. However, what if the mystery and its investigation was set up the other way around? What if there was no set solution and instead the solution to the mystery could be constructed from the clues uncovered by the players and their characters and would be, if not absolutely correct, then very nearly so? This is what Matrons of Mystery—and Brindlewood Bay, the roleplaying game by Jason Cordova it is derived from—both do.

The mystery—as opposed to the mysterious, which has always been there—has long been a part of roleplaying, all the way back to The Maltese Clue, the scenario published by Judges Guild in 1979. It really came to the fore with roleplaying games like Call of Cthulhu, Gangbusters, and Justice, Inc. and more recently seen in the GUMSHOE System with roleplaying games such as Mutant City Blues, which combines superheroes with the police procedural. What these all do with the mystery is provide the Game Matron with a plot and a set of clues that the players and their characters investigate the mystery and hopefully piece together the clues to uncover the mystery. However, what if the mystery and its investigation was set up the other way around? What if there was no set solution and instead the solution to the mystery could be constructed from the clues uncovered by the players and their characters and would be, if not absolutely correct, then very nearly so? This is what Matrons of Mystery—and Brindlewood Bay, the roleplaying game by Jason Cordova it is derived from—both do.Both Matrons of Mystery and Brindlewood Bay are Powered by the Apocalypse roleplaying games in which players take the roles of women of a certain age who investigate murder—often much to the consternation of local law enforcement. Brindlewood Bay has an American feel and behind the series of murders a Lovecraftian conspiracy, whereas Matrons of Mystery focuses entirely on the murder mysteries, employs a parred back version of the Powered by the Apocalypse mechanics, and has a decidedly British sensibility being inspired by television series such as Miss Marple, Rosemary & Thyme, Agatha Raisin, Queens of Mystery, Father Brown, and so on. This is not the world of the hardboiled mystery, or even mystery on a medium heat, but that of the ‘cozy’ mystery, set in a small town or village where everyone knows everyone—except that recently arrived stranger, and of course, everyone’s secrets—and there is a strong sense of community, and is of course, suitable for afternoon or Sunday night viewing with all of the family gathered round the television.

Matrons of Mystery: A cozy mystery roleplaying game is designed for three or four players, plus the Game Matron, and each mystery ideally takes a session to solve. This makes it good for one shots or convention games, and the familiarity of its genre means that Matrons of Mystery will be easy to grasp and familiar to most players. In Matrons of Mystery, players take the roles of ladies of a certain age, who are perhaps single, widowed, or divorced, certainly retired or have more than enough time to throw themselves into their community and various activities and charities. For example, keeping the parish church clean, attending meetings of the W.I., helping run Meals on Wheels, doing the village Christmas Pantomime, and so on. Of course, when murder strikes—as it invariably does in their surprisingly high murder count communities—it is the ‘Matrons of Mystery’ who take up their handbags, put down their trowels, and ever ready to make a nice hot cup of tea, discover whodunnit before the local bobby on the beat, Police Constable Plodd, and Inspector Witless from the nearest big town, can work it all out.

Character generation and game set-up in Matrons of Mystery is quite quick. First, the players name and decide on some details about their Matrons’ village. Then, every Matron has a name, a Personal Style, a Hobby, a Background, an Investigation Style, and a Contact. So a Name might be Audrey or Nettie, a Personal Style could be ‘Smart and Classic’, ‘Punk’, or ‘Twinset and Pearl’, and a Hobby Baking, Gardening, Collecting, or Amateur Dramatics. The Background consists of answers to three questions—the first is about a Matron’s former partner or whether or not she was married, what was her career before she retired, and whether she has any children, or if not, young relatives she is fond of. Her Investigation Style—Physical, Logical, Intuitive, or Gregarious—represents different approaches to solving mysteries, and the Contact is someone that the Matron knows well from her past and can rely upon to help out in a pinch. To create a Matron, a player decides upon all of these factors, answers the three questions for her Background, and then assigns +2 to her primary Investigation Style, +1 to her secondary Investigation Style, sets a third at 0, and assigns -1 to her least favoured Investigation Style.

Henrietta Wyndham

Personal Style: Punk

Hobby: Painting

Background: Divorced (to Nigel Wyndham, Stage name: Nasty Nigel), Former Record Producer, Children include Freddy, Pandora, Ned

Contact: Gordon Blythe-White (Record Exec)

Physical 0 Logical -1 Intuitive +1 Gregarious +2

Mechanically, Matrons of Mystery uses Powered by the Apocalypse. To undertake an action or ‘Move’, a player rolls two six-sided dice, adds his Matron’s Investigative Style and aims to roll high. The results fall into the ‘Yes’, ‘Yes, but…’, and ‘No and…’ Roll ten and more and the Move is successful; roll between seven and nine, and the Move is successful, but comes with a Complication; and roll six or less, and the Move not only fails, but adds a Complication. A Complication hinders the Matron’s investigative efforts, such as her slipping and injuring herself climbing in or out of a window or the suspect taking umbrage at one or more of the questions posed to him. This can lead to an ongoing Condition, such as a sprained ankle or being thrown out of a society dinner. (If there is one issue with Matrons of Mystery, it is that it could have done with a bigger list of Complications and especially Conditions to inspire the Game Matron.)

Rules are provided for gaining Experience Points and either using them in play to improve dice rolls or saving them to improve a Matron’s Investigative Styles. They do feel optional though.

Unlike most versions of Powered by the Apocalypse, the rules in Matrons of Mystery include an Advantage and Disadvantage mechanic. Thus when a Matron has the Advantage, which can come from her Personal Style, Hobby, Background, or the situation, three six-sided dice are rolled instead of two, and the best used. Conversely, when she is at a Disadvantage, her player rolls three dice and keeps the lowest two. Another difference between other roleplaying games using Powered by the Apocalypse and Matrons of Mystery is that it does not make use of Playbooks, each of which provide an archetypal character and its associated Moves. Instead, Matrons of Mystery provides a standard set of nine Moves that all of the Matrons can use. The first five Moves—‘Investigate’, ‘Interrogate’, ‘Take Action’, ‘Lend A Hand’, and ‘Ask A Favour’ are used to gain clues and conduct the Investigation. The next three, ‘Reminisce’, ‘Nice Cup of Tea and a Sit Down’, and ‘Go To Adverts’, enforce both the genre and the format of the genre. ‘Reminisce’ enables a Matron to recall something from her past which will help with the current investigation; ‘Nice Cup of Tea and a Sit Down’ lets two or more Matrons sit down, have a nice hot cup of tea, have a chat with each other, and in doing so, each remove a single Condition; and ‘Go To Adverts’ enforces a break in the story when a Matron is in danger, ends the scene on a cliffhanger, and lets the players discuss how the cliffhanger is resolved with the imperilled Matron unharmed when the adverts end!

The final Move is ‘Put It All Together’. This happens at the end or near the end of the game when the Matrons gather their collected clues and deduce the identity of the murderer. Instead of using an Investigative Style to modify the roll, the player uses the number of clues and secrets found out so far, minus the number of suspects involved in the murder. Typically, there are eight suspects per murder, so the Matrons will need to have gathered at least eight clues and secrets to negate this, plus more to gain a modifier to the roll. Roll ten or more and the Move is successful, the Matrons are correct in their deductions and have identified the Murderer and his motive; roll between seven and nine, and the Move is successful, the Matrons are correct in their deductions and have identified the Murderer and his motive, but there a Complication which the Matrons will need to overcome in order to apprehend the Murderer; and roll six or less, and the Move fails, indicating that the Matron’s deductions are incorrect. The Game Matron has to explain why and then sends the Matrons back off to continue their investigations and try again.

For the Game Matron, there is good advice on designing a mystery, from the theme and the set-up through to defining the secrets and listing the clues. There is also good advice on running the game—both online and at the gaming table, how to handle clues, secrets, Complications and Conditions, and so on, as well as optional rules for one-on-one play and playing away from the Matrons’ home village. A short bibliography provides some inspiration for the Game Matron. Then there are three ready-to-play Mysteries, complete with set-up, teaser, eight suspects, and a long list of clues. The first is ‘Gardner’s Question Crime’ in which the village hosts the popular radio show, Gardeners’ Answers in the grounds of Hatherly Hall. With most of the village present, the guest speaker, celebrity gardener and host of the television series, Gardener’s Life, Alan Jefferson, drops dead as he is about to take to the stage. This is followed by ‘Dicing With Death’ in which the village hosts a roleplaying convention (!) and award-winning game designer, Scott Sallow, is found dead on the last day of the convention with his mouth stuffed full of polyhedrals! Lastly, ‘Ding Dong Death’ is takes place just before national bell ringing championships and with the village wanting to put on a good performance, the bell ringing team is getting in some last-minute practice. Unfortunately, the lead bell ringer, Walter Bell, is found hanging upside down from one of the bell ropes. All three scenarios are great set-ups, though ‘Dicing With Death’ feels both improbable and a direct appeal to its intended audience.

Physically, Matrons of Mystery is a tidily done digest-sized book. The cover is appropriately rural, whilst the internal artwork, all publicly sourced, is there to break up the page rather than necessarily illustrate the game. The book is well written and easy to read—especially with the slightly larger fount size.

Matrons of Mystery is fun to play and it is simple to play. Having just the one set of nine Basic Moves eases play no end. Given the age of the Matrons, it is much more of a social game than physical game necessarily, although some sneaking around is probably going to be necessary and perfectly in keeping with the genre. Although it does present her with eight suspects to roleplay, the lighter nature of the rules do provide the Game Matron with the opportunity to really focus on her roleplaying and have fun with it too. The nature of the game and its ‘no given perpetrator’ set-up also strips Matrons of Mystery of any sense of stress or competition which might arise in the players and the Game Matron as they worry whether their deductions and solution to the crime is actually right. Instead, the players and their Matrons construct the murder solution and motive from the clues, thus emphasising storytelling—both the storytelling of the murder and the storytelling of it being solved.

Matrons of Mystery: A cozy mystery roleplaying game is cleverly cozy, taking the structure of Brindlewood Bay and parring it back to focus on its core game play. It is a smart, sprightly roleplaying game which delightfully evokes its genre from the page to the table. And if you are going to play this at the table, a nice hot cup of tea is an absolute necessity.

Character Creation Challenge: Arthur Holmwood Lord Godalming

In the book Arthur Holmwood, later the Lord Godalming, is the other suitor for the hand of Lucy and the one she ultimately chooses. One of the plot threads in the books and made more clear in the 1992 movie, was that Holmwood, Seward, and Morris were all friends and even had a few adventures together.

I recall at the time of the 1992 movie that there were rumors of a possible prequel involving the "Victorian Young Guns" and their fights with the supernatural before Dracula. Neat idea, but all three were fairly incredulous at the idea of the supernatural when Van Helsing brings up the topic.

Still, Holmwood is pretty important to the tale because not only is he Lucy's suitor, he provides the money and the title to get the heroes all the things they need. Holmwood is also the one that drives the stake into Dracula's heart in the novel.

Cary Elwes provides one of the best performances, but I am also rather partial to Michael Gough in Hammer's 1958 Dracula and Simon Ward in 1973's Dracula which questionably featured Jack Palance as Dracula.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Arthur Holmwood

Arthur Holmwood4th level Veteran

Archetype: Victorian Lord

Strength: 12 (0)

Dexterity: 15 (+1) P

Constitution: 13 (+1) S

Intelligence: 12 (0)

Wisdom: 11 (0)

Charisma: 16 (+3) S

HP: 22

Alignment: Neutral Good

AC: 8

Attack: +2

Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+2/+0Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: +1Saves: +2 to all saves.Powers: Combat Expertise, Improved damage, improved defense, Supernatural Attack, tracking

Skills:** History, Convince, Literature, Wilderness Survival

** Skills are optional in NIGHT SHIFT, but for Seward, Holmwood, and Morris I feel they are what set the characters apart and above and beyond their class abilities.

--

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

[Free RPG Day 2021] Tomb of the Savage Kings

Now in its fourteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2021, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 16th October. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Of course, in 2021, Free RPG Day took place after GenCon despite it also taking place later than its traditional start of August dates, but Reviews from R’lyeh was able to gain access to the titles released on the day due to a friendly local gaming shop and both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in together sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles. Reviews from R’lyeh would like to thank all three for their help.

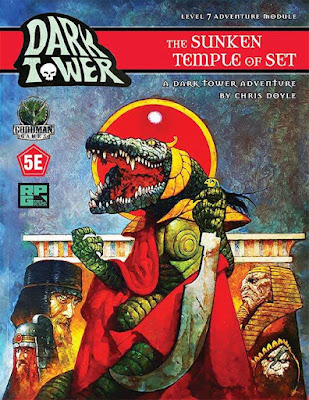

—oOo— Goodman Games provided two titles to support Free RPG 2021, both of which were highly anticipated. Perhaps the more interesting of the two was Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set, an expansion for Dark Tower, the classic and highly regarded scenario written by Jennell Jaquays and published by Judges Guild in 1979. However, the other was as eagerly anticipated since it was for Goodman Games’ highly popular Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. In past years, the support for Free RPG Day has come in the form of a quick-start, either for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game or Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic, but for Free RPG Day 2021, the support came in the form of a scenario, Tomb of the Savage Kings.

Goodman Games provided two titles to support Free RPG 2021, both of which were highly anticipated. Perhaps the more interesting of the two was Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set, an expansion for Dark Tower, the classic and highly regarded scenario written by Jennell Jaquays and published by Judges Guild in 1979. However, the other was as eagerly anticipated since it was for Goodman Games’ highly popular Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. In past years, the support for Free RPG Day has come in the form of a quick-start, either for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game or Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic, but for Free RPG Day 2021, the support came in the form of a scenario, Tomb of the Savage Kings.Tomb of the Savage Kings is a short adventure for Second Level characters which shares an Egyptian theme with Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set. There the similarities end, for Tomb of the Savage Kings, for although there is a Pulp sensibility to both, that sensibility is one of Pulp Fantasy and Swords & Sorcery in Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set, whereas it one of Pulp Horror for Tomb of the Savage Kings as it draws on Universal Studio’s The Mummy and The Mummy’s Hand, as well as Hammer Studio’s The Mummy for its inspiration. In fact, the sensibility is so strong in Tomb of the Savage Kings, that if there was such a thing as Pulp Crawl Classics, this would be a perfect scenario for it.

The scenario begins with the players being hired by Portnelle’s most popular and wealthy socialite, the widow Zita Aztur. Her sister, Isobel, smitten with a mysterious suitor who fancies himself as an adventurer, and has gone missing. The widow fears that she has run off with this would be adventurer in search of the Moon Spear of Andoheb, said to be located in the latter’s pyramid tomb. If true, she fears for her sister’s life as everyone up until now who has searched for the spear has never been seen again. With promise of a handsome payout and the good widow’s Halfling servant along as a guide, the scenario begins with the Player Characters outside of the tomb looking for a way in…

Once inside, the Player Characters find a classic Egyptian tomb complex. It consists of just nine locations and packs into that the traps, undead, treasures, and clues typical of the genre. It is definitely worth the Player Characters’ searching for clues as there are signs that someone has been here before—and recently! Those clues are nicely done in a grand depiction of the life of Andoheb, and the Judge should definitely provide it as a handout to her players. Following these and exploring the pyramid should bring the Player Characters to a fantastic climatic confrontation which plays much on the inspiration for Tomb of the Savage Kings and depending on what happens, have some interesting outcomes. Two of these have links to the scenarios, Dungeon Crawl Classics #66.5 Doom of the Savage King and Dungeon Crawl Classics #77.5 The Tower out of Time, and so the Judge may want to have access to those.

Physically, Tomb of the Savage Kings is as well presented as you would expect for a scenario from Goodman Games. The artwork, the cartography clear, and the scenario is well written, though it needs an edit in place.

Tomb of the Savage Kings is a great adventure for Free RPG Day which can be played in a single session. The theme—and probably the plot—will be familiar to many a gamer, especially if the players like Pulp Horror depictions of Egypt. It does also suggest that perhaps there is further potential in an Egypt-set or Egypt-like setting for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game or a more Pulp Horror setting. For fans of the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game who like their fantasy with steamy mix of Pulp Horror, Tomb of the Savage Kings is fun adventure.

Have a Safe Weekend

Entitled Goose Game

Imagine if you will a haunted house home to several ghosts in danger of being woken up by the constant ringing of bell stolen from the nearest village by a giant, enraged and dressed only in a silk bathrobe, who is trying to find the three ne’er do wells who have stolen his golden goose and run into the house to hide. The house is called Willowby Hall, the goose is called Mildred, the giant is called Bonebreaker Tom, the ghosts are Elias Fenwick, evil occultist, the aristocratic Lavinia Coldwater, the footman, Horatio, and a Taxidermied Owl Bear, the adventurers are Helmut Halfsword, Lisbet Grund, and Apocalypse Ann, and they all really, really want something. And as the bell rings out, the house shudders and shudders until floors collapse, rooms catch alight spontaneously, the Taxidermied Owl Bear goes on the hunt, and the undead rise from where they are buried about the house… This is a recipe for, if not a pantomime a la Mother Goose, then a dark farce best played out on Halloween or at Christmas, but either way is the set-up for the scenario, The Waking of Willowby Hall. Written by the host of the YouTube channel, Questing Beast, it is designed for a party of Third Level characters for the retroclone of your choice and can easily be adapted to other roleplaying games too. It would work with Hypertellurians: Fantastic Thrills Through the Ultracosm or Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay as much as it would Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy.

Imagine if you will a haunted house home to several ghosts in danger of being woken up by the constant ringing of bell stolen from the nearest village by a giant, enraged and dressed only in a silk bathrobe, who is trying to find the three ne’er do wells who have stolen his golden goose and run into the house to hide. The house is called Willowby Hall, the goose is called Mildred, the giant is called Bonebreaker Tom, the ghosts are Elias Fenwick, evil occultist, the aristocratic Lavinia Coldwater, the footman, Horatio, and a Taxidermied Owl Bear, the adventurers are Helmut Halfsword, Lisbet Grund, and Apocalypse Ann, and they all really, really want something. And as the bell rings out, the house shudders and shudders until floors collapse, rooms catch alight spontaneously, the Taxidermied Owl Bear goes on the hunt, and the undead rise from where they are buried about the house… This is a recipe for, if not a pantomime a la Mother Goose, then a dark farce best played out on Halloween or at Christmas, but either way is the set-up for the scenario, The Waking of Willowby Hall. Written by the host of the YouTube channel, Questing Beast, it is designed for a party of Third Level characters for the retroclone of your choice and can easily be adapted to other roleplaying games too. It would work with Hypertellurians: Fantastic Thrills Through the Ultracosm or Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay as much as it would Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy.The Waking of Willowby Hall was funded via a Kickstarter campaign as part of ZineQuest 2. It comes as a thirty-two-page adventure built around thirty-three named locations across the three floors of Willowby Hall and eight NPCs plus various monsters. The house is not mapped out and detailed once, but twice. First in the module’s opening pages, marked with thumbnail descriptions and page number references, the latter actually more useful than simple numbers. Second, in the latter half of the book where full room descriptions are given accompanied by a complete floorplan with the particular rooms highlighted. It feels a little odd at first, but flipping between the two is actually not as awkward as it first seems. None of the individual rooms in Willowby Hall are mapped, but it is a classic mansion which when combined with the engagingly detailed descriptions is easy to visualise and portray. The NPCs are each given half a page, including stats, personality, and wants (or motivations) , plus a fetching illustration. This includes Mildred the Goose, who is essentially there to do two things. One is to motivate her previous owner, Tom Bonebreaker, and the other is to annoy the hell of out the players and their characters. If it appears that the Dungeon Master is playing Untitled Goose Game with Mildred, then both she and Mildred are probably doing their job. Tom Bonebreaker however, is accorded a full page to himself as he is the scenario’s main threat. The scenario’s other threat is also given its own page.

For the Player Characters, the first difficulty is getting into Willowby Hall. Several reasons are suggested as to why they might want to enter the mansion. This includes a couple of classics—one of the Player Characters inheriting the mansion, the other the mansion being the retreat of an occult society which collected rare artefacts and books—as well as the Player Characters merely passing and being hired by the local villagers to retrieve the bell. The latter will probably lead to the Player Characters negotiating with the giant campanologist for the bell and he will want his goose back, which means they will have to enter Willowby Hall. With the other ideas, they will are unlikely to encounter this and instead the Player Characters will just need to make a run for the mansion. This is made easier in the scenario because it advises that Tom Bonebreaker be on the other side of the building when they make their run across the overgrown lawns to the mansion. Alternatively, the Player Characters could begin in the mansion itself and the adventurers simply charge in with goose in hand and the giant on their tails. Once inside, the Player Characters are free to explore as is their wont, but then their problems are only beginning…

The Player Characters’ first aim is probably going to be working out what is going in the house as they explore its halls and rooms, the second being to locate the trio of adventurers and probably, Mildred. As they make their search, there is the constant sound of the bell being rung outside and the eye of Tom Bonebreaker appearing at one window after another, and if the giant spots anyone, the immediate danger of him reaching in to grab whomever he can. The tolling of the bell though is a timing mechanism and as it clangs again and again, the house changes. Slowly at first, and only slightly, but then more rapidly and more obviously. This builds and builds, giving The Waking of Willowby Hall a timing mechanism, one which can easily be adjusted for single, one-off play at a convention or slightly longer play as part of campaign. It gives a sense of dynamism to the scenario.

Physically, The Waking of Willowby Hall is clearly and simply presented. The maps are easy to use, the descriptions of the various rooms engaging, and the illustrations excellent in capturing the personalities of the NPCs. In fact, they are so good that you almost wish that they and Willowby Hall itself was available as a doll’s house and a set of paper standees to use as the Player Characters explore the mansion and that giant eye keeps appearing at various windows. Add in some sound effects—at least the sound of the bell and the honking of the goose—and what a scenario that would be!

The Waking of Willowby Hall gives the Dungeon Master everything necessary to run the scenario, not least of which is a great cast of NPCs for her to roleplay—and that is before you even get to Mildred. After all, what good Dungeon Master would turn down the opportunity to roleplay a goose? The Waking of Willowby Hall is great fun, both raucous and ridiculous, combining elements of farce with a classic haunted house and a countdown ’til the bell tolls for thee.

—oOo—

An unboxing of The Waking of Willowby Hall can be found here.

Character Creation Challenge: Dr. John "Jack" Seward

My next three characters are the ones that get forgotten the most. While Mina and Lucy will have their names changed/swapped, the next three are either reduced to one or two characters or forgotten about altogether.

Today I want to do one close to my heart, Dr. Jack Seward. Seward was a psychiatrist and I spent a number of years as a psychologist. Plus my one and only time on stage was playing Seward in my High School version of Dracula. Yeah, I am not going to dump my academic career for a life in the limelight, but it was fun.

My favorite performance of Seward was from Bram Stoker's Dracula from 1992 played by Richard E. Grant, though Donald Pleasence also gave a great performance in 1979's Dracula.

Seward's role in the novel is to first be a suitor to Lucy, but he also brings in Van Helsing. His friends Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris are also instrumental in the battle against Dracula.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Yeah, me with a full beard in High School as SewardDr. Jack Seward3rd level Sage

Yeah, me with a full beard in High School as SewardDr. Jack Seward3rd level SageArchetype: Would-be suitor, doctor

Strength: 11 (0)

Dexterity: 12 (0) S

Constitution: 13 (+1)

Intelligence: 16 (+2) P

Wisdom: 12 (0) S

Charisma: 15 (+2)

HP: 14

Alignment: Lawful Good

AC: 9

Attack: +1

Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+1/+0Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: 0Saves: +3 to saves against spells and magical effects.Powers: Mesmerize Others (used on Renfield and Mina), Suggestion, Survivor Skills (level 1), Languages (16), Arcane Dabbler

Survivor Skills

- Open Locks: 15%

- Bypass Traps: 10%

- Sleight of Hand: 20%

- Move Silently: 20%

- Hide in Shadows: 10%

*In this case "Spells" will be just bits of lore and learning he is able to use.

Skills:** History, Knowledge (Psychiatry), Medicine, Science

** Skills are optional in NIGHT SHIFT, but for Seward, Holmwood, and Morris I feel they are what set the characters apart and above and beyond their class abilities.

--

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Friday Fantasy: The God With No Name

The God With No Name is a dungeon within the body of remains of a giant beast or god. Published by Leyline Press this is a setting more recently seen in Genial Jack Vol. 2 from Lost Pages and Into the Würmhole, the Free RPG Day release in 2021 for Vast Grimm. Instead of the dry, hard rock walls of caves and worked stone of corridors and rooms, such dungeons possess an organic, moist, often pulsating, and even fetid environment. However, they may also have calcified and fossilised over time, leaving behind an organic imprint of caves and tunnels. The God With No Name combines elements of both—the organic and the calcified. It is also noticeable for its format. Like The Isle of Glaslyn before it, The God With No Name manages to fit an adventure onto the equivalent of four pages and then present it on a pamphlet which folds down to roughly four-by-six inches. It contains all of the room descriptions on one side and the maps and various tables on the other. It is the very definition of a clever little design. Ultimately however, it is a design which places constraints on the scenario.

The God With No Name is a dungeon within the body of remains of a giant beast or god. Published by Leyline Press this is a setting more recently seen in Genial Jack Vol. 2 from Lost Pages and Into the Würmhole, the Free RPG Day release in 2021 for Vast Grimm. Instead of the dry, hard rock walls of caves and worked stone of corridors and rooms, such dungeons possess an organic, moist, often pulsating, and even fetid environment. However, they may also have calcified and fossilised over time, leaving behind an organic imprint of caves and tunnels. The God With No Name combines elements of both—the organic and the calcified. It is also noticeable for its format. Like The Isle of Glaslyn before it, The God With No Name manages to fit an adventure onto the equivalent of four pages and then present it on a pamphlet which folds down to roughly four-by-six inches. It contains all of the room descriptions on one side and the maps and various tables on the other. It is the very definition of a clever little design. Ultimately however, it is a design which places constraints on the scenario.The God With No Name is designed for use with Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy and ostensibly details a network of tunnels and caves mined by ancient Dwarves for its very pure salt deposits. It is still said that not all of those deposits have been mined out, but the mine has long been abandoned and it is said that the local Mountain Folk revere the mine as a god. The valley below the mine is said to be infested with trolls and the mine full of secrets. There is a truth to a great many of the rumours about the mine… The mine consists of two levels, a longer main tunnel and a shorter cliff tunnel. The entrance to the main tunnel is at ground level, the entrance to the cliff tunnel above in the cliff face. Above that is a small tower. It is depicted in both cross section and a floorplan with cartography by Dyson Logos.

The long abandoned mine has in parts the feel of Tolkien’s Moria, a sense of mystery and age, but there is also something squamous to it too, as well as something of the film Alien, for parts of the mine—or rather ‘The God With No Name’—are still alive and the shadows seem to move… This is because the god is not merely dead, but slumbering, even if for time immemorial, and the shadows are infested by the Void Doppler, the shadow child of ‘The God With No Name’ who stalks the living in search of body parts so that it can be reborn and walk under the sun. It leaves behind secretions of the void, and those void secretions spread as the Player Characters delve deeper and deeper, blocking off access to parts of the mine, including the way back out…

In addition to the descriptions of the mine’s locations and maps, The God With No Name is supported with a set of tables which provide rumours, encounters outside and inside the mine, and the contents of unmarked rooms. The table of rumours also works as a set of hooks to involve the Player Characters as there is no given set-up or hook to the scenario, and the table of valley encounters as a means to expand the adventure and flesh the scenario out a little more. The size and isolated nature of The God With No Name also means that it is relatively easy to drop into a Dungeon Master’s campaign.

There is scope in The God With No Name for some nasty, horrifying sessions of play, as the Player Characters are hunted from the shadows and their body parts are stolen one by one. However, the scenario is not without its issues, which either stem from its physical design or its tone. Physically, the fold up pamphlet design of The God With No Name means that its content feels constrained and having the descriptions on one side and the map on the other—when folded out, let alone folded up—does mean that in actual play, the scenario is not as easy as it should be to use. The scenario has no set-up or hooks for the Player Characters to get involved, so the Dungeon Master will have to create those, though she can, of course, make use of the given rumours table. Perhaps the biggest issue with the scenario is the tone and genre. Although this is a dungeon adventure, it is very much a ‘you’re locked in a room with a monster’ horror scenario a la the film Alien, its horror is not just of the dark and the shadows, but also of the body. As a body horror scenario, it creeps up on both the Player Characters and the Dungeon Master, and whilst it should be doing the former, it should not be doing the latter. Some warning to the prospective Dungeon Master should have been given upfront. Also, the scenario does not state what Player Characters Levels it is designed for, but the nature of the monsters encountered—trolls in the valley and the Void Doppler in the mine—suggest at least Fifth and Sixth Levels.

Physically, The God With No Name is a piece of design concision. It is compact and thus easy to store, but format does not make it easy to use. It is not illustrated bar the front cover and as to the cartography, Dyson Logos’ maps here are not his best, or even his most clear. The scenario does require a slight edit though.

Its compact size and content means it needs a little development upon the part of the Dungeon Master, but The God With No Name is creepy and not a little weird. If the Dungeon Master wants a short—two sessions or so—body horror scenario for her campaign, then The God With No Name certainly delivers.

Character Creation Challenge: Lucy Westenra

Yesterday I featured Mina Murray Harker, the hero of the Dracula novel. The archetypical victim though belongs to her friend Lucy Westenra. I have compared Lucy and Mina a few times. Showing where Mina is the "Modern Woman," Lucy is the "Old World Woman." She does a lot to make herself more attractive to Dracula. She is looking for a man to define her life, she is a member of the "idle rich," she has bouts of sleep-walking, her innocence, and more. Where Mina is proactive, Lucy is largely reactive.

It is hard really not to feel bad for her.

After she is turned by Dracula all of that gets inverted. The sweet, coquettish girl becomes the dangerous "bloofer lady" that preys on children.

My favorite portrayal of her comes from Sadie Frost in 1992's Bram Stoker's Dracula, but I also rather liked how Jan Francis looked as the vampire Lucy (or rather "Mina" in this version) in 1979's Dracula, though she looks nothing like the "bloofer lady." Though the most accurate physical portrayal was by Katie McGrath in the short run NBC series Dracula.

Here she is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Lucy Westenra2nd level Survivor (Supernatural, Vampire)

Lucy Westenra2nd level Survivor (Supernatural, Vampire)Archetype: Vampire Victim

Strength: 11 (0)

Dexterity: 12 (0)

Constitution: 8 (-1)

Intelligence: 11 (0) S

Wisdom: 10 (0) S

Charisma: 17 (+3) P

HP: 4

Alignment: Chaotic Evil

AC: 9

Attack: +1

Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +2/+1/+0Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: 0Saves: +3 to all Wisdom saving throws, +3 to death saves. +1 to all others.Powers: Vampire Powers, Stealth skills, Climbing, Danger Sense (1-2), Sneak Attack x2

Vampire Powers

Vampire Powers- Ability Bonuses (+2 to Strength, +2 Dexterity)

- Damage Immunity

- Feed on Life (Con drain)

- Vampire Regeneration

- Vampire Vulnerabilities

Stealth Skills

- Open Locks: 25%

- Bypass Traps: 20%

- Sleight of Hand: 30%

- Move Silently: 30%

- Hide in Shadows: 10%

- Perception: 45%

--

Dracula, and Lucy for that matter, drains Constitution, not "Levels," which is as it should be for "Dracula." There was no way Lucy could survive three attacks of draining 2 levels when she is always described as frail and weak before Dracula even shows up. Not only that the children Lucy later preys one are certainly 2nd level, they are barely 0 level.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Character Creation Challenge: Mina Murray Harker

Longtime readers here will know of my love of Mina Murray Harker, the true hero of the Dracula novel. I have talked about her here a few times, but in short, she is the one that puts all the pieces together, she is the one that has the forethought to transcribe everyone's notes. She is the one that really has the tools to go hunting for Dracula. She is also the prototype of the "Final Girl" a trope that will only grow for the next 120+ years.

One thing I have never cared for though was the whole reincarnated lover of Dracula. Mina is interesting enough without needing to add anything else to her character. That being said, I did not mind Alan Moore making her into a vampire. But that is not what I am going with her. This is Mina from the book and most of the movies.

Here she is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Mina Murray Harker

Mina Murray Harker3rd level Survivor (Human)

Archetype: Survivor

Strength: 10 (0)

Dexterity: 12 (0)

Constitution: 15 (+1) S

Intelligence: 16 (+2) P

Wisdom: 12 (0)

Charisma: 16 (+2) S

HP: 11

Alignment: Light

AC: 8

Attack: +1

Fate Points: 1d8

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+1/+0Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: 0Saves: +3 to death saves. +1 to all others.Powers: Stealth skills, Climbing, Danger Sense (1-3), Sneak Attack x2, Read Languages,

Stealth Skills

- Open Locks: 35%

- Bypass Traps: 30%

- Sleight of Hand: 40%

- Move Silently: 40%

- Hide in Shadows: 30%

- Perception: 50%

--

Mina is a vampire attack survivor, more so that she survived an attack by Dracula. That has to count for something.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

“For Your Consideration”

[Free RPG Day 2021] Root: The Bertram’s Cove Quickstart

Now in its fourteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2021, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 16th October. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Of course, in 2021, Free RPG Day took place after GenCon despite it also taking place later than its traditional start of August dates, but Reviews from R’lyeh was able to gain access to the titles released on the day due to a friendly local gaming shop and both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in together sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles. Reviews from R’lyeh would like to thank all three for their help.

Published by Magpie Games, Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is a roleplaying game based on the award-winning Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, about conflict and power, featuring struggles between cats, birds, mice, and more. The Woodland consists of dense forest interspersed by ‘Clearings’ where its many inhabitants—dominated by foxes, mice, rabbits, and birds live, work, and trade from their villages. Birds can also be found spread out in the canopy throughout the forest. Recently, the Woodland was thrown into chaos when the ruling Eyrie Dynasties tore themselves apart in a civil war and left power vacuums throughout the Woodland. With no single governing power, the many Clearings of the Woodland have coped as best they can—or not at all, but many fell under the sway or the occupation of the forces of the Marquise de Cat, leader of an industrious empire from far away. More recently, the civil war between the Eyrie Dynasties has ended and is regroupings its forces to retake its ancestral domains, whilst other denizens of the Woodland, wanting to be free of both the Marquisate and the Eyrie Dynasties, have formed the Woodland Alliance and secretly foment for independence.

Published by Magpie Games, Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is a roleplaying game based on the award-winning Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, about conflict and power, featuring struggles between cats, birds, mice, and more. The Woodland consists of dense forest interspersed by ‘Clearings’ where its many inhabitants—dominated by foxes, mice, rabbits, and birds live, work, and trade from their villages. Birds can also be found spread out in the canopy throughout the forest. Recently, the Woodland was thrown into chaos when the ruling Eyrie Dynasties tore themselves apart in a civil war and left power vacuums throughout the Woodland. With no single governing power, the many Clearings of the Woodland have coped as best they can—or not at all, but many fell under the sway or the occupation of the forces of the Marquise de Cat, leader of an industrious empire from far away. More recently, the civil war between the Eyrie Dynasties has ended and is regroupings its forces to retake its ancestral domains, whilst other denizens of the Woodland, wanting to be free of both the Marquisate and the Eyrie Dynasties, have formed the Woodland Alliance and secretly foment for independence.Between the Clearings and the Paths which connect them, creatures, individuals, and bands live in the dense, often dangerous forest. Amongst these are the Vagabonds—exiles, outcasts, strangers, oddities, idealists, rebels, criminals, freethinkers. They are hardened to the toughness of life in the forest, but whilst some turn to crime and banditry, others come to Clearings to trade, work, and sometimes take jobs that no other upstanding citizens of any Clearing would do—or have the skill to undertake. Of course, in Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, Vagabonds are the Player Characters.

Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’, the mechanics based on the award-winning post-apocalyptic roleplaying game, Apocalypse World, published by Lumpley Games in 2010. At the heart of these mechanics are Playbooks and their sets of Moves. Now, Playbooks are really Player Characters and their character sheets, and Moves are actions, skills, and knowledges, and every Playbook is a collection of Moves. Some of these Moves are generic in nature, such as ‘Persuade an NPC’ or ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’, and every Player Character or Vagabond can attempt them. Others are particular to a Playbook, for example, ‘Silent Paws’ for a Ranger Vagabond or ‘Arsonist’ for the Scoundrel Vagabond.

To undertake an action or Move in a ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, a character’s player rolls two six-sided dice and adds the value of an attribute such as Charm, Cunning, Finesse, Luck, or Might, or Reputation, to the result. A full success is achieved on a result of ten or more; a partial success is achieved with a cost, complication, or consequence on a result of seven, eight, or nine; and a failure is scored on a result of six or less. Essentially, this generates results of ‘yes’, ‘yes, but…’ with consequences, and ‘no’. Notably though, the Game Master does not roll in ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game.

So for example, if a Player Character wants to ‘Read a Tense Situation’, his player is rolling to have his character learn the answers to questions such as ‘What’s my best way out/in/through?’, ‘Who or what is the biggest threat?’, ‘Who or what is most vulnerable to me?’, ‘What should I be on the lookout for?’, or ‘Who is in control here?’. To make the Move, the player rolls the dice and his character’s Cunning to the result. On a result of ten or more, the player can ask three of these questions, whilst on a result of seven, eight, or nine, he only gets to ask one.

Moves particular to a Playbook can add to an attribute, such as ‘Master Thief’, which adds one to a character’s Finesse or allow another attribute to be substituted for a particular Move, for example, ‘Threatening Visage’, which enables a Player Character to use his Might instead of Charm when using open threats or naked steel on attempts to ‘Persuade an NPC’. Others are fully detailed Moves, such as ‘Guardian’. When a Player Character wants to defend someone or something from an immediate NPC or environmental threat, his player rolls the character’s Might in a test. The Move gives three possible benefits—‘ Draw the attention of the threat; they focus on you now’, ‘Put the threat in a vulnerable spot; take +1 forward to counterstrike’, and ‘Push the threat back; you and your protected have a chance to manoeuvre or flee’. On a successful roll of ten or more, the character keeps them safe and his player cans elect one of the three benefits’; on a result of seven, eight, or nine, the Player Character is either exposed to the danger or the situation is escalated; and on a roll of six or less, the Player Character suffers the full brunt of the blow intended for his protected, and the threat has the Player Character where it wants him.

Root: The Bertram’s Cove Quickstart is the Free RPG Day 2021 from Magpie Games for Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game. It includes an explanation of the core rules, six pregenerated Player Characters or Vagabonds and their Playbooks, and a complete setting or Clearing for them to explore. From the overview of the game and an explanation of the characters to playing the game and its many Moves, the introduction to the Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game in Root: The Bertram’s Cove Quickstart is well-written. It is notable that all of the Vagabonds are essentially roguish in nature, so in addition to the Basic Moves, such as ‘Figure Someone Out’, ‘Persuade an NPC’, ‘Trick an NPC’, ‘Trust Fate’, and ‘Wreck Something’, they can ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’. This covers Acrobatics, Blindside, Counterfeit, Disable Device, Hide, Pick Lock, Pick Pocket, Sleight of Hand, and Sneak. Each of these requires an associated Feat to attempt, and each of the six pregenerated Vagabonds has one, two, or more of the Feats depending just how roguish they are. Otherwise, a Vagabond’s player rolls the ‘Trust to Fate’ Move.

The six pregenerated Vagabonds include Dara the Adventurer, a kindly Owl in search of friends and justice who prefers to subdue her opponents; Sherwin the Harrier, a highly competitive Squirrel always on the move; Clip the Ronin, a well-mannered Raccoon Dog who knows how to trick those in charge; Umberto the Raider, a sturdy axe-wielding Mouse and former bandit with a love of battle; Rattler the Pirate, a Mouse who is truly at home on the water; and Lucasta the Raconteur, a Weasel who is an outstanding performer. Most of these Vagabonds have links to the given Clearing in Root: The Bertram’s Cove Quickstart and all are complete with Natures and Drives, stats, backgrounds, Moves, Feats, and equipment. All a player has to do is decide on a couple of connections and each Playbook is ready to play.

As its title suggests, the given Clearing in Root: The Bertram’s Cove Quickstart is Bertram’s Cove. Its description comes with an overarching issue and conflicts within the Clearing, important NPCs, places to go, and more. Once again, the overarching issue is the independence of the Clearing. Bertram’s Cove is an important fishing port at the mouth of the Alberdon River on the eastern shore of the Grand Lake. An important Marquisate military and supply base, the Woodland Alliance has been providing support to the local rebels and spurred on by mysterious rebel hero, Captain Sparrowhawk, rebel pirates have been harrying Marquisate shipping in the area. The townsfolk of Bertram’s Cove have done well under the obedient peace of Marquisate military occupation, but many want their freedom and will do anything to achieve it. The conflicts include determining quite how far the rebels in the town are willing to go, finding a missing spy who might be able to identify the rebels in Bertram’s Cove for the Marquisate governor, searching for the treasure lost aboard a sunken Marquisate courier vessel, and ultimately, saving Captain Sparrowhawk. There is advice on how these Conflicts might play out if the Vagabonds do not get involved and there are no set solutions to any of the situations. For example, an attempted bombing by the rebels will go wrong if the Vagabonds do not intervene or get involved, leading to martial law and all fishing on the lake being banned—which would be a disaster for the port. All of Bertram’s Cove’s important NPCs are detailed, as are several important locations. Bertram’s Cove is a scenario in the true meaning—a set-up and situation ready for the Vagabonds to enter into and explore, rather than a plot and set of encounters and the like. There is a lot of detail here and playing through the Bertram’s Cove Clearing should provide multiple sessions’ worth of play.