An alien force has invaded one galaxy after another. Assaulted one world, followed by another. Reduced colonies to glass and moons to floating collections of rubble. Civilisation is at the invader’s mercy, and as hard as it fights and as desperately as it fields one more newly developed weapon, it cannot withstand the onslaught. How long before survivors huddling on isolated worlds with oxygen and food supplies dwindling are all that is left? Soon, but perhaps there is one last hope, the fabled Reaper’s Gambit. Myth and legend say that it can be found on a world beyond the borders of civilisation, buried deep underground. Now that world has been located and an expedition been sent to excavate a possible site for the device. So far, the Bridge, a Landing Pad, and Ship’s Power has been established on the world along with a force of Marines. It is time to begin digging, exploring, researching, and defending.

This is the set-up for

UMBRA: A Solo Game of Final Frontiers from the publisher of

RISE: A Game of Spreading Evil and

DELVE: A Solo Map Drawing Game. All three are map-drawing games for one player and each involves the drawing and building, populating and defending, and exploring and exploiting of great underground networks. Both

RISE and

DELVE are fantasy games, themed around building and exploring dungeons and telling the story involved in this.

UMBRA is a Science Fiction solo roleplaying and journaling game inspired by the Science Fiction and Science Fiction horror of

Alien, the

Halo and

Dead Space video games,

The Thing, and

Starship Troopers. In the game, the player takes the role of the Commander of an expeditionary base. From one turn to the next, as Commander, they will manage, expand, and defend the colony as well as sending out excavation and exploration teams which continue to dig out and dig down deep below the planet’s surface in order to locate the Reaper’s Gambit. Managing primarily means ensuring that the base has sufficient power and food to survive. Expanding the colony means constructing new facilities—barracks, crew quarters, charging stations, fabrication bays, genetic labs, power plants, hydroponics, cloning bays, alien beacons, research laboratories, and much, much more.

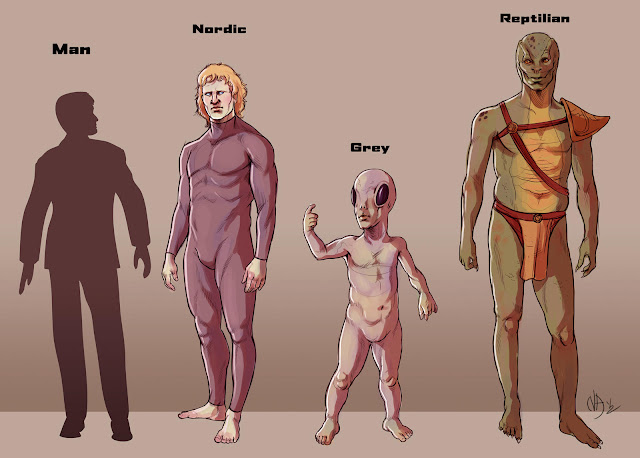

To defend the base, the Commander can recruit Marines and Hackers, build Support Droids and Robots, clone Mutants, and hire Alien Mercenaries. Once they have built a Fabrication Bay, they can begin installing automated machine guns, laser grids, psychic mind crushers, and more, whilst installing barriers—both defensive and offensive, and even secret passages, the latter to get around invading enemies. Together, they may need to defend the base against alien hive drones, war drones, and many more threats.

Exploring means finding resources, funding, natural formations, remnants, and other things. Natural formations include chambers full of eggs containing parasites; eruptions of lava; and strange anomalies. A remnant could be a monolith strange markings which might scan an adjacent area or turn some Marines hostile; a buried alien probe which a hacker could hack; or a dormant war machine already to go to battle…

The designer’s previous games in this family have all been about exploring and building underground—

DELVE: A Solo Map Drawing Game about exploring and building down and

RISE: A Game of Spreading Evil about exploring and building up.

UMBRA: A Solo Game of Final Frontiers is also about exploring and building down, but it adds a new dimension—the outside. Or rather the surface. A colony breach at the surface can cause decompression and loss of units not protected behind airlocks; armed aliens might stage an invasion; an alien ship might conduct a strafing run or an asteroid might crash into the base; and once a Motor Pool has been constructed, Expeditions on the surface can be launched and discoveries made, such as finding a strand alien mercenary, a previously undiscovered civilisation, and even a lost relic.

To play

UMBRA, the player will need squared paper, a deck of ordinary cards, some tokens to represent units, a notepad in which to record the expedition’s progress, and pen and pencils. They will also need dice—a four-sided die at least. The game starts with the player drawing the Bridge, Landing Pad, and Ship’s Power on the grided paper at the top. Then on each turn, they choose an unexplored location on the map—which is a cross section of the base and its underground facilities—and draw a card to determine what is found. Hearts are Resources, Diamonds are Funding for hiring troops, Spades are natural formations, and Clubs are remnants. Both natural formations and remnants require the player to draw another card and refer to the respective tables. Combat is a matter of attrition, comparing the Strength values of the combatants and deducting the lower Strength value from the higher Strength value. A troop unit whose Strength is reduced to zero is removed from the Hold, but a Medbay on the same level where the unit died can revive it. The rules also allow for ranged combat. The player can trade and exchange Resources for Funding or vice versa, and finally they can build new features in the base—facilities, security features, and much, much more, and hire new troop units.

Once the Commander has excavated to the Level Five and beyond, the deck of playing cards’ Jokers are added back into the deck. When drawn Black Jokers represent Alien Terrors, bigger challenges that the Commander will need to overcome, and Red Jokers are Alien Artefacts which will help them in the long term. When the Red Joker is drawn, two further cards are drawn to determine its traits, and if they are face cards, then the Commander has located the Reaper’s Gambit. In which case, it is shipped off to support the Galactic War, the base and its facilities are given full colony status, and so the player has achieved victory in their play through of

UMBRA! If however, enemy units reach the base’s Bridge, defeats the troops there, the base has been overrun or captured, and the Commander’s efforts to find the Reaper’s Gambit thwarted. The Galactic War will continue until the civilisation is destroyed—and so the player has been defeated in their play through of

UMBRA.

If a player is victorious, they need not stop playing. There is something dark and dangerous in the abyssal depths of the planet, a truly monstrous threat—perhaps one greater in the long run to that being faced in the Galactic War.

UMBRA contains options also for theming the planet’s levels, for terraforming the planet and making it even more difficult to explore, and a list of challenges that the player can overcome and so gain a little glory. Rounding out

UMBRA is a selection of prompts and a quick reference page for ease of play.

Physically,

UMBRA: A Solo Game of Final Frontiers is a cleanly presented, digest-sized book. The writing is clear and simple such that the reader can become a Commander and start exploring and drawing with very little preparation.

UMBRA: A Solo Game of Final Frontiers is closest in design to

DELVE: A Solo Map Drawing Game. Both are sedate in their play with strong procedural and resource management elements, and these elements along with the map—or rather floor plans of the base in the case of UMBRA—are what the player builds and tells their story around.

UMBRA can be played in one sitting or put aside and returned to at a later date, but it does take time to play and the more time the Commander invests the more rewarding the story which should develop. And as good as successfully finding the Reaper’s Gambit feels, playing

UMBRA: A Solo Game of Final Frontiers and not finding it and having the base fail can be as narratively interesting and satisfying—if not more so. The story of discovering that tale though, might be for another roleplaying game and an entirely different session.

The A to Z of Conspiracy Theories: I is for Illuminati

The A to Z of Conspiracy Theories: I is for Illuminati