The island of Avallen is one of legend and song. The oldest legend and first song tell of the Wild Hunt, how great heroes of the Vallic peoples stepped into the Otherworld or Annwn where ultimately, they sacrificed themselves to stop Avallen from being plagued by abominations known as Ffieidd-Dra. The victors of the Wild Hunt returned and were acclaimed by their peoples, becoming the ‘Divine Briendal’, or immortal god-kings and god-queens of the five clans that exist to this day. Rivalry between the clans and the ‘Divine Briendal’ led to civil war. The resulting bloodshed would undermine the divine power and influence of each of the god-kings and god-queens as followers either lost their lives or their faith. It was this that brought the wars to an end and made the Briendal to retreat into the Annwn and swear a pact never to intervene in the affairs of the Vallic again. Yet songs of their legend continue to be sung by bards to this day, along with the legends and tales of other heroes who were influenced by the Wild Hunt and then had their own songs. The island of Avallen is one that cries out for legend and song, for heroes and adventurers, for it is a land under threat and a land divided.

The abominations known as Ffieidd-Dra, such as the water-borne Afanc or the mighty porcine Ysgithyrwyn, each driven by a hatred of the Briendal, break through from the Otherworld and spread chaos and destruction. Fiends, like the seductive Baobhan Sith and the cursed Werefolk, also slip through from the Otherworld to spread their malign influence. The undead, ghosts, and vengeful Spirits, all known as the Unshapen, remain in the mortal realm, as yet unwilling to let go and enter the Otherworld. Otherworldly predators, the Wyrd, such the Adar Llwch, great dust eagles which grant great rewards to the winners of the games of riddles they favour and peck the losers to death, or Cat Sith, which feeds off the spirits of both the dead and the living, hunt both the Otherworld and the real world. The Fae can be equally as dangerous, though sometimes their curiosity can make them commit acts of kindness too. These are not the only threats to the Vallic, but there is one that divides them rather than is common to all of the clans. Roughly a generation ago, the Raxian Empire invaded. Aided by the strong ties and an alliance formed by decades of trade with the most southerly clan, Pen Cawr, the Raxian Empire set out to add the barbarous peoples of the island which lay off its western coast at the end of the world, but the defeat of its army by an alliance of the other clans prevented further expansion. Not all of the Pen Cawr clan have accepted the presence of the Raxians, but the assimilation has seen a continued Raxian military presence, Raxian construction techniques and writing being taken, and Raxian culture practices accepted, even as the Raxians adopt the worship of the gods of the Vallic—if only for protection.

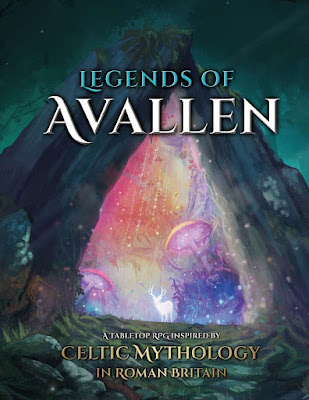

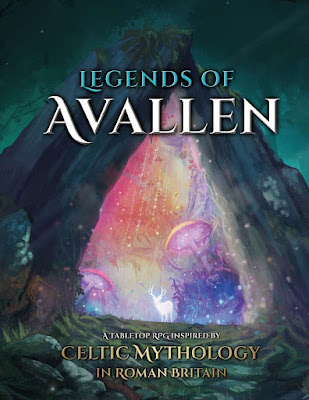

This is the setting for

Legends of Avallen: A Tabletop RPG Inspired by Celtic Mythology in Roman Britain, published by

Adder Stone Games. Although inspired by the historical situation of the Roman invasion of Britain in the first century AD, this is not necessarily a roleplaying about the conflict between the invaders and the invaded, but rather a roleplaying game about keeping the land and its people safe, about protecting it from incursions from the Otherworld, and about men and women who grow beyond their ordinary lives to become heroes and forge legends that the bards will sing of in tales down the ages.

Legends of Avallen maps this out, so that such men and women—the Player Characters—begin life with a simple Profession, such as Crafter, Priest, Scribe, Tamer (of animals), or Thief, and after a Quest or two, take up an adventuring Class, like Warrior or Mage, before going on to follow a Legendary Path like Druid, Gladiator, or Slayer. A player can select a Class at Level Two and a Legendary path at Level Five, and then follow that all the way to Level Fifteen. Now there are some obvious paths for a Player Character. For example, a Tamer would become a Reaver and then a Slayer; a Scribe a Mage and then a Magister; and a Bard a Mystic, and then a Fili. However, a Player Character is free to follow whatever path his player decides, so whilst

Legends of Avallen provides the framework and structure, it leaves the choices to the player. It does one other thing though and that is make following Legendary Paths difficult. To earn each ability of a Legendary Path—and a Player Character can switch back and forth between several—a Player Character must complete a trial. The book suggests several for the various abilities across all of the Legendary Paths. What this means is that Player Character progression is mere accumulation of Experience Points, but a chance to be tested, and whether or not the Player Character succeeds, to turn that into a storytelling and roleplaying opportunity.

A Player Character in

Legends of Avallen has four attributes—Agility, Spirit Vigour, and Wit. These range in value between -1 and +5. He also has a Profession, of which there are ten to choose from. These are Alchemist, Bard, Crafter, Merchant, Priest, Scavenger, Scribe, Socialite, Tamer, and Thief. His Personal Aspects include Motivation, Virtue, and Flaw, and he also has an Origin, Name, and Appearance. Origin will be from one Avallen’s five Clans or the Raxian Empire, and provides typical names and appearances. The process of character creation is simple. The player assigns +1 to one attribute and -1 to another, and then chooses all the rest. The book even suggests Motivations, Virtues, and Flaws that the player can choose from so that they remain unrelated.

Iulia is the eldest daughter of Caeso, a retired military commander with mercantile interests in Port Magnus. Her younger brothers currently serve in the army elsewhere in the Empire. She helps run her father’s business as he is getting older and is not as well as he once was. She fears that with this news, her brothers will be called back to take over, whereas she wants to take control herself and perhaps do some good with her wealth.

Name: Iulia

Origin: Raxian

Appearance: Raven haired

Profession: Socialite

Motivations: I will rise to the top (Influence)

Virtues: I help the needy (Benevolent)

Flaws: My image is everything (Vain)

Vigour -1 | 0 Agility

Spirit +1 | 0 Wit

Expertise: Politics, Etiquette, Courtship

Abilities: Introduce

Beyond that, there are four Classes to choose from at Level Two—Mage, Mystic, Reaver, and Warrior, and ten Legendary Paths to follow at Level Five. These include Druid, which can shapeshift; the luck-based Fae Touched; Fili, a bard who casts magic through music; Gladiator, a warrior who uses flourishes to enhance his combat ability; Magister, a mage who enhance his spells in numerous, often challenging ways; Maleficus, a mage who can bind Unshapen and other lost spirits; Primus, a commander who shapes the battlefield for his allies; Slayer use openings to strike at and take down dangerous creatures; Swyn-Pict, a warrior who paints himself in dyes to protect himself and even draw ethereal weapons from; and Teulu, a protective warrior who increases his Fury as he is hit, using it to enhance his defence and damage. In addition, every Player Character and potential legendary hero has a character arc reflected in mechanics that will see each gain both Resolve and Burdens—overcoming the latter to gain the former, suffer a Descent into self-doubt, undergo Transformation in the course of rising from the Descent, before ultimately, achieving Recognition as to whether the Player Character is a hero or an anti-hero.

Mechanically,

Legends of Avallen uses a standard deck of playing cards as its resolution system, including the Jokers. Each of the four attributes is tied to one of the four standard suits. Thus, Hearts for Vigour, Diamonds for Agility, Spades for Spirit, and Clubs for Wit. They are paired three times. First into physical attributes by colour, Vigour (Hearts) and Agility (Diamonds), and mental by colour, Spirit (Spades) and Wit (Clubs). Second, into strength and endurance attributes—Vigour (Hearts) and Spirit (Spades), and into speed and subtlety attributes—Agility (Diamonds) and Wit (Clubs). Third, into diagonally opposing attributes, Vigour (Hearts) versus Wit (Clubs) and Spirit (Spades) versus Agility (Diamonds). When a player wants his character to undertake a task, he draws a card and checks both its rank and if it matches the colour or suit of the attribute being used. Ordinary numbered cards are worth one rank, whilst Court cards are worth two. If the colour of the card matches that of the attribute, it is worth an extra rank, or two extra ranks if it matches the suit. The Joker that matches the colour of the attribute, generates four ranks. These ranks are added to the attribute value.

Conversely, the card’s rank—one if a number card and two if a Court card, is subtracted from the attribute value if it does not match the attribute’s colour. This is doubled if the card is of the suit opposite to that of the attribute. A Joker which does not match the colour of the attribute subtracts four ranks from the attribute. The final result is compared with the Check Difficulty of the task to see if the Player Character is successful. The typical Check Difficulty is one, but can be lower or higher. The result can be a Critical Success, Success, Failure, or Critical Failure, depending on the card drawn. Both a Critical Success and a Failure will earn the Player Character an Edge, but his opponent an Edge on a Critical Failure.

Fortunately for a Player Character, the outcome of an action or task does not just rest on the turn of a single card. A Player Character can gain Advantage from a situation, from someone helping him, or from an ability. Each level of Advantage allows a player to draw an extra card and use the best one. Being at a Disadvantage forces a player to draw an extra card for each level of Disadvantage and use the worst one, although levels of Advantage and Disadvantage do cancel each other out. Edge is essentially a card that the player draws and keeps face down until the task or action that his character needs to succeed, in which case it is used to give his character Advantage. If a Player Character is on the verge of failure, he can also Exert himself or his equipment to upgrade a Failure to a Success, if being opposed, to downgrade an Opponent’s Success to a Failure. However, this means that the Player Character cannot exert himself again until he rests, if his equipment was used, that the item is now broken and cannot be used at all.

Mechanically, the system is simple enough, but its nuances are not easily taught and do take some adjusting to. Nor is it immediately obvious what the Check Difficulty should be for each test. However, once that adjustment is made, the advanced rules come together more easily. Combat has a stripped back feel, with attacks being made using Agility (Diamonds) against an opponent’s Agility—though some weapons favour other attributes, damage being determined by the weapon and the attacker’s Vigour (Hearts), defence by the opponent’s Armour Rating, derived from his armour and his Vigour. If hurt, a combatant does not lose ranks of Vigour, but is simply wounded. Of course, one reaction to this would be for the defender to Exert himself or his equipment to avoid such an outcome. Combat also covers grappling, ambushes, sneak attacks, and more, but also offers tips for the players, the most important of which are co-operation and strategise, rather than to simply rush in.

Similarly, magic in

Legends of Avallen is designed to be challenging. Both Mystic and Mage spells have a Complexity rating, ranging from one to four, which acts as Disadvantage when the caster attempts to cast the spell. The caster can also increase the scope and range of a spell, but that also raises the Complexity. So apart from the simplest of spells—which can become more flexible as the Mage Mystic grows in power and is capable of overcoming the extra Complexity—it pays for the caster to prepare, whether that is having the right equipment, setting up a ritual, and so on.

Legends of Avallen pays particular attention to both journeys and socialising. The rules for overland travel are not that dissimilar to that of

The One Ring, with the Player Characters taking particular roles—Gatherer, Guide, Lookout, and Scout—each keyed to one of the suits in the playing deck. Having someone in each role will negate most dangers unless a Danger or Opportunity arises, then it is primarily down to the Player Character in that role to overcome the Dangers or gain from the Opportunity. Suggested Dangers and Opportunities are given for each role. The roleplaying game’s social mechanics come into play when an NPC has an Objection to co-operating with the Player Characters or allowing them to undertake a particular course of action. When this occurs, the Player Characters enter into a Parley with the NPC into an attempt to overcome the Objection, and do so before he loses his Patience—again, not dissimilar to the interaction rules in

The One Ring. Roleplaying and interaction are encouraged, but much like spellcasting, preparation can greatly advantage the Player Characters, as can Incentives which will give them Advantage. The Motivations, Virtues, and Flaws of the Player Characters can also come into play, as can the social standing for both the Player Characters and the NPC. Although there are parallels here with The One Ring, the mechanics for

Legends of Avallen are their own and their card-based nature gives them a very different feel.

In terms of background,

Legends of Avallen gives a good overview of Vallic society, the clans and the Raxians and their lands, with the latter including a selection of Otherworldly Tales found within those lands which the Game Master can potentially build stories around. For the Game Master there is solid advice on running the game and her roles when doing so, including narrator, judge, and creator. The latter includes a guide to creating quests. The Bestiary also includes guidelines for Game Master to create her own NPCs and monsters as well as give them trophies which the Player Characters can loot, and in the case of the Alchemist and the Scavenger Professions turn into useful items, such as potions, weapons, armour, and so on. Rounding out Legends of Avallen is ‘The Sealing Stone’, a starting quest which is very nicely structured and sees the Player Characters help restore a relic and search for the persons last sent to restore it, but are now missing.

Physically,

Legends of Avallen is a stunning looking book, beautifully illustrated with quite lovely artwork. It is well written, although it needs an edit in places, and a better index would make the book more accessible. That said, the rules are succinctly written with a minimum of fuss and numerous examples. The setting does use a lot of Welsh, especially in name places and monsters, but a pronunciation is included at the beginning of the book.

Legends of Avallen: A Tabletop RPG Inspired by Celtic Mythology in Roman Britain is an impressive roleplaying game. It has a setting which feels both familiar and different, shifting the conflict away from the historical of Celts versus Romans, to one of protecting the land from the dangers and wonders of the Otherworld. Ultimately,

Legends of Avallen is a roleplaying game about quests and becoming great heroes and legends, with succinct mechanics and a structured route that together encourage storytelling and adventure.

—oOo—

The Kickstarter for

Against the Faerie Queene – A Celtic Campaign for LoA & 5E, the first supplement for

Legends of Avallen: A Tabletop RPG Inspired by Celtic Mythology in Roman Britain is currently running.

Name: Gold FeverPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: Gold FeverPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.