1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that

Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game,

Wizards of the Coast, released the new version,

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

In the beginning there was

Dungeons & Dragons. This made a lot of people happy, but it also made some people unhappy, and it even made some people both happy and unhappy. The happy people played it, the unhappy people refused to play it and campaigned to stop the people playing it because their sense of fun was entirely devoted to doing something else which they felt the people playing it should be doing, and the people it made both happy and unhappy, thought they could do better, including the very people who were happy with

Dungeons & Dragons because they had made it. And the people who thought they could do better than

Dungeons & Dragons either tried to make new, better versions of

Dungeons & Dragons, or they tried to create versions of their own which were better, faster, more fun, more realistic, and well, just not

Dungeons & Dragons. Some would be very close to

Dungeons & Dragons, others far away, and others…? Well however close these fantasy heartbreakers were, most would remain the province of the Game Master and his gaming group, but others would come to market and some would succeed, some fail… and some would achieve legendary, even cult status. None more so than

The Spawn of Fashan.

Self-published by

Kirby Lee Davis in 1981,

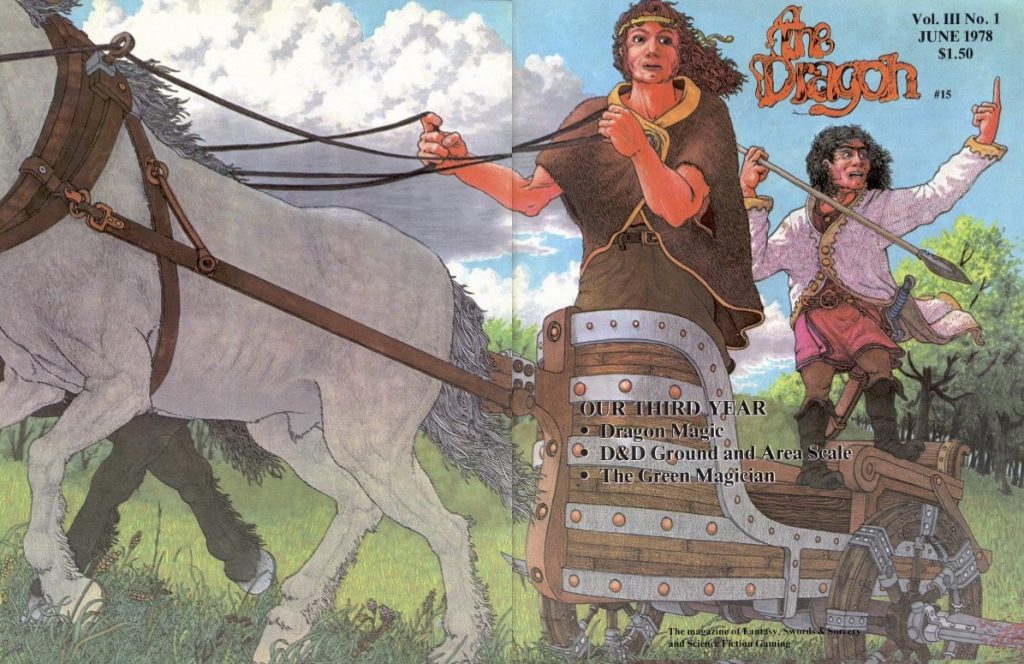

The Spawn of Fashan would sell only a handful of copies, but gave rise to an infamous review in

Dragon #60 by Lawrence Schick who could not believe that anyone would create a roleplaying game as dreadful as

The Spawn of Fashan and very quickly concluded that, “

The Spawn of Fashan is a great parody of role-playing rules!” That issue of

Dragon was published in April, 1982, and a combination of an incredulous review and the possibility that the whole review was not about an actual roleplaying, but one entirely made up, and was thus an April Fool’s joke upon the part of Schick and

Dragon magazine, meant that

The Spawn of Fashan passed into legend. That legend would be kept alive by its inclusion on the ‘REAL MEN, REAL RÔLE-PLAYERS, LOONIES AND MUNCHKINS’

lists which parodied early gamer archetypes and stereotypes, as in Loonies “play a variant Spawn of Fashan” as their favourite SFRPG and as their Favourite King Arthurian RPG, “play a variant of Spawn of Fashan so variant it shouldn't be called Spawn of Fashan anymore”. However,

The Spawn of Fashan is real, and due to actual demand, a number of reprints were published in 1998, followed by a fortieth anniversary edition in 2021. It is the latter version, which is being reviewed here, notably because, getting hold of any other version, is hideously expensive.

So what is

The Spawn of Fashan and what is

The Spawn of Fashan about? It is a Class and Level roleplaying game written in response to the lack of individuality in any one character in

Dungeons & Dragons. As to what it is about,

The Spawn of Fashan is not really a setting as such, more—definitely much more—a set of rules for character creation and combat. What background there is suggests that Fashan is a world reduced to the level of a mediaeval economy by a nuclear war and in addition to leaving high tech artefacts to be found, the nuclear war also resulted in areas of radiation and a background radiation high enough that minor psionic abilities are common amongst the all-Human descendants of the survivors. So technically,

The Spawn of Fashan is not so much a fantasy roleplaying game as a post-apocalyptic one. Either way, it is actually based on

The Annals of Fashan, a series of fantasy novels by the designer, the setting and background for which did not make it into the final draft of

The Spawn of Fashan. Had it done so, the roleplaying game would have been longer, but it might actually have been more interesting in terms of setting, storytelling, and roleplaying potential. The designer though wanted to avoid giving away the plots of the novels. Nevertheless, any Referee and group of players roleplaying

The Spawn of Fashan would still be roleplaying a version of Fahsan—though not the designer’s Fashan—hence every other campaign being a ‘spawn’ of Fashan. Which begs the question, ‘When are you playing

The Spawn of Fashan, but not playing

The Spawn of Fashan?’, since it is almost impossible to play in Fashan because there is so little of the setting in

The Spawn of Fashan such that any campaign of

The Spawn of Fashan cannot actually be set on Fashan…

That said, what do you play in

The Spawn of Fashan? Well, all Player Characters

The Spawn of Fashan are human. A character has eight statistics—Strength, Dexterity, Reflexes, Constitution, Intelligence, Charisma, Courage, and Senses. Actually, there ten statistics, as a Player Character can also have Courage and Courage as well as Courage, but only if he has extra special fighting abilities. Anyway, all but Senses are rolled on five six-sided dice (or as

The Spawn of Fashan puts it, “five 1-6 dice”) and the lowest one dropped, except if a character is female, in which case, “The number of dice rolled at any time for strength, constitution, and hit points is halved.” This is despite the fact that in the book’s introduction the designer states that neither he nor his team are sexist in terms of the pronouns used in the book. Which is fine except he is sexist in terms of game design. Anyway, female characters are fine, because they gained increased Charisma and Intuition. Unfortunately, the designer ultimately never actually defines what Intuition is… and actually getting find that out involves following the instruction, “[see the ‘Destiny’ listing on the Mental Illness table].” which leaves to wonder why it is defined on a Mental Illness table and if that means that all female characters—because they have Intuition—on Fashan are mentally ill? Once you have found the Mental Illness table in the fifty-one pages of Section VII which both contains all of the charts for

The Spawn of Fashan and take up more than half of

The Spawn of Fashan, a section supposedly for the Referee’s eye’s only, the actual entry on that table reads, “Destinied. Character is destinied. Referee should roll on the Destiny Table for the character.” However this immediately followed by a note which states, “Due to the necessity of having the Destiny Table interlock with the Referee's cultures and history, it is not given here.” So essentially, not only are female characters impaired in

The Spawn of Fashan, as written in

The Spawn of Fashan, they cannot be created using its rules unless the Referee has already defined a world or campaign setting where intrinsically, they are not equal to men. The good news is that for

The Spawn of Fashan, this is only the start.

First though, a character needs not one, but two character-types. These are occupations and include Bandits, Barbers, Beggars, Carpenters, Construction Workers, Creepers, Farmers, Healers, Mercenaries, Merchants, Metal Forgers, Miners, Misfits, Occultists, Priests, Sailors, Specialists, Stone Cutters, Swayers, Teachers, Thieves, Traders, Trappers, and Wood Cutters. Once the relevant table is found—and this is a phrase which could be repeated again and again with

The Spawn of Fashan—the Referee rolls on the table according to area the Player Character is from to determine his Parents’ Choice of character-type and the player choses his character’s Childhood Choice character-type. This does not seem to have any effect except if the Parents’ Choice of character-type is Misfit, in which case, the Player Character’s character-type is also Misfit. The actual explanation of the character-types are listed in the dreaded section of Section VII and for the most part are fairly obvious and straightforward, sometimes giving statistic increases, equipment, and the like. The less obvious character-types include the Creeper, men of darkness known as Shadowers, the Occultist, renowned and hated for exerting control over the societies of Fashan with their mind control, and the Swayer, the dreaded masters of persuasion. In particular, Creepers can exude a black, inky cloud that most cannot see through; the Occultist can enter into a trance and cause anyone nearby to stutter and be indecisive or to suffer seizure, depending his Intelligence; and Swayers are so persuasive that their words can require a Saving Roll to withstand.

Some character-types, like, can have Senses, the ability to detect life and also food and provisions. There is, however, no magic in

The Spawn of Fashan and no religion or gods in

The Spawn of Fashan, the latter more because in

The Spawn of Fashan there is no real setting. Which means that the Priest character-type has no role until the Referee has defined her own ‘spawn’ of Fashan. In addition to rolling for Statistics, a player rolls on fourteen tables for eyesight, sense of smell, hearing, taste, body (to give advantages and disadvantages rather than a body type), insight, intellect, mental illness, phobia, compulsion, hand usage, height and weight, learned abilities, and language. Some of these require Saving Rolls on a twenty-sided die, but for the most part they generate a completely random selection of abilities and facts. For example, the character has Independent Eye Movement, is allergic to particular type of animal which the Referee will determine, has Heavy Sound Good Hearing (bonus to initiative versus heavy plodders), can tell poison in the water and drink, is double-jointed and has superhuman strength, has Sense of Life, is a Gambler and gets bonuses the riskier the situation, is Destinied (see above for how that is left up to the Referee to determine), fortunately has no phobias, has the compulsions of being a Coward, suffers from Daydreams, and Practices every action, is 5’ 6” and 139 lbs, and because he has an Intelligence of twenty or more, is an ‘Expert on Subterrainian Passages’.

Without a doubt, character generation in

The Spawn of Fashan is inaccessible, obtuse, overwritten and unnecessarily complex—and that is just the six or so steps of creating a character, including rolling for Luck Factor and starting Bank Notes, and does not take into account the numerous secondary and derived values the roleplaying game employs. Nor does it take into account the time needed. In fact, no matter how long that time is, it is simply too long. As much as the means and the rules do provide the degree of individuality that the designer wants, whether or not that degree of individuality is either wanted or warranted, they are simply not presented in a manner to help either the player or the Referee through the process.

Then there are the mechanics to

The Spawn of Fashan. The core mechanic is the Saving Roll on a twenty-sided die and roll high, but for a roleplaying game of its vintage, it should be no surprise that the bulk of the mechanics in

The Spawn of Fashan focus on combat. However, there is a sense of combat being a static affair with neither side involved actually moving, so just an exchange of blows, though movement is covered in surprise and initiative (including when neither party can detect the other because they are both dead—including the Player Characters). Combat involves yet another splurge of terms and terminology and factors that Referee and player has to take into account before either has to roll, including how hard the attacker wants to hit, where he wants to hit, then if the defender parries or dodges (rolled on a percentile dice rather than the standard twenty-sided die), consulting tables as necessary, and making a Saving Throw if the level of damage suffered is equal to or greater than the Serious Injury Tolerance Level. If the attack is successful, rolls are made to see if the armour itself is damaged, point by point, and… if the defender is not actually dead by this point, it is difficult not to believe that anyone—in the game or out—still has the will to live, let alone continue playing… Thankfully though, the people of Fashan are so insecure that they do not congregate in groups of more than thirty, so there are no armies on Fashan, and so need for rules handling army combat.

Surprisingly, the advice on ‘The Makings of a Campaign’ is a decent read and avoids much of the incoherency found throughout the rules. They are backed up by tables for random encounters and generating locations, including ruins and dungeons, and two examples. One is a setting, the other is of actual play. Whilst the monsters have absurd names such as Arl-Grats, Bactrolo, Bartaln, Bull Makl, Cronalk, Filcornect, Larnex, Lorsenfolo, Purtorfalm, Rolmtrokl, and Transgrusan, the setting is equally as silly, which describes the land of Boosboodle in the ‘Boosboodle Inner Human Habitation Zone’ (Bihhz) through which flows The River Mazoo, travel to the towns of Jugble and Crumbudz, and when all else fails, tells the Player Characters that they can go ‘North, where Melvin is Standing Now.’ It is both silly and intentionally humorous upon the part of the designer, but mostly comes across as just plain silly. The other is the example of play. It is without a doubt, the worst example of play in any roleplaying game before

Hackmaster Basic. It recounts how a Player Character Thief, Sook, enters a general store in Biddles, the capital of Boosboodle and attempts to buy first some armour, then a religious artefact, followed by a hoe, and lastly, a metal chest. When that succeeds, the player has Sook throw it at the merchant and kill him. It is clear from the writing that boredom has set in on either side, with the Referee resorting to sarcasm and the player to random acts purely to get a response. It is a truly terrible, but funny piece of writing because it is at such odds with the po-faced tone to the rest of

The Spawn of Fashan.

Where

The Spawn of Fashan, 40th Anniversary Edition is actually interesting is in the essays which appear at the front of the reprint. Here the author talks how he brought the roleplaying game to fruition not once but three times! First at its conception and its subsequence appearance at Denvention II in 1981, followed by renewed interest from roleplayers in both the late eighties and the late nineties, the latter leading to a reprint and inclusion of the first essay. Third, and more recently, its publication upon its fortieth anniversary. Both retrospectives are interesting in highlighting how challenging it was to bring something like

The Spawn of Fashan to print then, and how ambitious the author was in doing so. They also allow him time to reflect upon his creation and the hobby’s response to it, and it is clear that he readily accepts rather than resents the latter—especially with regard to the lack of a table of contents or index for example. There can be no doubt that a roleplaying game with as legendary a reputation as

The Spawn of Fashan is deserving of both essays where other roleplaying games of such ilk may not be.

Physically,

The Spawn of Fashan is as bad as you possibly imagine. It is laid out in the style of a newspaper rather than a book and its text is dense, and notoriously unedited, being riddled with spelling mistakes and inconsistencies and cross references which lead the reader down a blind alley. There are few illustrations and to be fair, they add very little to the overall tone or feel of the book.

The Spawn of Fashan, 40th Anniversary Edition at least does come with an index and a table of contents—the original version and its reprint did not and one can only imagine how daunting it must have been to find anything—anything at all—in the book.

—oOo—

The Spawn of Fashan was reviewed three times following its initial publication, first by Charles Dale Martin in

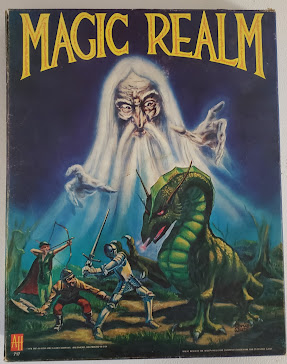

Different Worlds Issue 19 (February 1982). Amongst the many elements he criticised of the roleplaying game were the combat system, writing that, “The combat system is both complex and unwieldy. It imposes too great a strain on the players and the referee - using these rules is rather like playing Gladiator, Traveller and Arduin Grimoire simultaneously. Bunetluest, Bushido and Chivalry & Sorcery provide more realism for less effort.” He was equally critical of the game’s treatment of female characters and of the publisher wrote, “The Fashan co-op seems to be out of touch with the adventure gaming community. The game was released at a science fiction convention. The only other role-playing systems mentioned are

D&D,

AD&D,

The Fantasy Trip and

Magic Realm. I am familiar with fifteen fantasy role-playing systems and I must conclude that, despite honest effort,

Spawn of Fashan is several years behind the state of the art.” However, concluded that, “…[I]t may still be worth buying. The referee’s notes are excellent guidelines for any fantasy campaign. Game masters of an eclectic bent may wish to use some of the new character classes and the many tables in their own game systems. And some adventurous souls might play the game and enjoy it.”

Then there was the infamous review in Dragon #60 (April 1982) by Lawrence Schick, titled ‘Don’t take Spawn of Fashan seriously’. His initial impression was of it being “…[O]ne more mediocre rewrite of the D&D® rules.” but then, “As I read the 96-page rulebook (list price $8.95), my initial boredom was gradually replaced by confusion, amazement, and finally delight. At first glance, the rules seem badly organized and poorly written. The opening sections are deluged with pages of ill-defined jargon and numerous confusing references to tables apparently placed elsewhere. By the time I reached the rules quagmire entitled “Combat,” I could only wonder in amazement that any set of rules could be this bad.” He continued, “Then the light started to dawn. Plowing through the monstrous Tables and Charts section, I began to grin, and by the end of the book, I was laughing loudly. The Spawn of Fashan is a great parody of role-playing rules!”.

Lastly, Ronald Pehr reviewed

The Spawn of Fashan in

The Space Gamer Number 49 (March 1982). He described

The Spawn of Fashan as “…[A] fascinating set of fantasy combat rules which are trying to become a full role-playing game.” and that “…[I]ts current value seems limited to experienced FRPG players who want something novel. Beginners will be baffled, and gamers happy with their current rules will find little reason to journey to the far planet of Fashan.”

—oOo—

There have been some notoriously bad roleplaying games published over the course of the hobby’s history. Efforts like

F.A.T.A.L.,

Myfarog, and

Racial Holy War are justly reviled for their inherent offensiveness and the ignorance of the values espoused by the authors. Make no mistake,

The Spawn of Fashan does not deserve to be placed alongside that excrescent trinity and it would be insulting to the author to think otherwise. However, that does not mean that

The Spawn of Fashan is not a bad game—far from it.

The Spawn of Fashan is terrible game. Dense, overwritten, and incomprehensible with a formidable learning curve hampered by poor, oh so poor cross referencing and interminable page flipping, all accompanied by a hilariously awful example of play. Even trying to explain the rules in

The Spawn of Fashan is akin to rewriting and not just simplifying them, but translating them. Yet there are flashes of potential here, for the notes for the Referee’s notes and philosophies on worldbuilding are not without merit, which leads the reader to wonder quite what a subsequent edition of

The Spawn of Fashan could have been like in the hands of a more experienced production and development team. And wonder quite that because lurking within the game’s stodgy writing, there is a game which by the standards of the time could have been made better and more accessible and more playable. Of course, the appearance of any such subsequent edition might well have done much to negate the reputation of the first edition (at least partially). As the essays in the front of

The Spawn of Fashan, 40th Anniversary Edition make clear, it was not to be. Despite its legendary reputation,

The Spawn of Fashan is real, it is not a parody, and with the availability of

The Spawn of Fashan, 40th Anniversary Edition, you too can find out just how bad it really is, what optimism and faith in your own vision can create, and how sometimes, even if you really do not like

Dungeons & Dragons, you really cannot do better. As bad as it is, and because it is as bad as it is, Kirby Lee Davis is to be commended for reassessing it again and letting us reassess it with the release of

The Spawn of Fashan, 40th Anniversary Edition.

Goodman Games provided two titles to support Free RPG 2021, both of which were highly anticipated. One was Tomb of the Savage Kings, an adventure for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. The other was potentially much more interesting. As its name suggests, Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set is an expansion for Dark Tower, the scenario written by Jennell Jaquays and published by Judges Guild in 1979. The scenario details a dungeon built around two buried towers contested over by followers of Set and Mitra and the surrounding lands and has a strong Eastern Mediterranean and Egyptian flavour. Regarded as a classic, Dark Tower was included in ‘The 30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time’ at number twenty-one in the ‘Dungeon Design Panel’ in Dungeon #116 (November 2004)—notable because it was the only third-party scenario to be included on the list. In March, 2021, Goodman Games announced it had acquired Dark Tower from the Judges’ Guild, and would republish it for use with both Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition and the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game.

Goodman Games provided two titles to support Free RPG 2021, both of which were highly anticipated. One was Tomb of the Savage Kings, an adventure for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. The other was potentially much more interesting. As its name suggests, Dark Tower: The Sunken Temple of Set is an expansion for Dark Tower, the scenario written by Jennell Jaquays and published by Judges Guild in 1979. The scenario details a dungeon built around two buried towers contested over by followers of Set and Mitra and the surrounding lands and has a strong Eastern Mediterranean and Egyptian flavour. Regarded as a classic, Dark Tower was included in ‘The 30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time’ at number twenty-one in the ‘Dungeon Design Panel’ in Dungeon #116 (November 2004)—notable because it was the only third-party scenario to be included on the list. In March, 2021, Goodman Games announced it had acquired Dark Tower from the Judges’ Guild, and would republish it for use with both Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition and the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game.

What’s new?

What’s new?

Articles

Articles