1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that

Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version,

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is important for several reasons—all of them firsts. It was the first scenario written by David ‘Zeb’ Cook for TSR, Inc. It was the first scenario in the ‘I’ series—I for Intermediate, designed for Player Characters of between Fourth and Seventh Level. It marked the first appearance of the monsters, the Aboleth, the Yuan-ti, the Mongrelmen, and the Tasloi in

Dungeons & Dragons, whilst many of its other monsters would be drawn from the then recently published

Fiend Folio. It was one of the first scenarios for TSR, Inc. to be heavily influenced by the Conan stories of Robert E. Howard. And if it was not the first sandbox scenario for

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, First Edition, then it was one of the earliest. For many reasons,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is regarded as a classic and in 2004, was ranked the thirteenth greatest

Dungeons & Dragons adventure of all time by

Dungeon magazine for the thirtieth anniversary of the

Dungeons & Dragons.

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City began life as a tournament scenario for 1980

Origins Game Fair and when originally accepted, was intended to be part of the ‘C’ or Competition series of scenarios. This is very much evident in the design of the module and has profound consequences upon its play and its development. Similarly, its inspiration—the Conan short story,

Red Nails, has profound consequences upon its play and its development, though nowhere near as much as its origins as a tournament scenario. (Notably, Cook would later design The

Conan Role-Playing Game published by TSR, Inc. in 1985.) It is set in a deep rift valley in a faraway jungle, a lost city in the vein of the stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs and H. Rider Haggard, and of the story of archaeologist and explorer, Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett, who would inspire Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s

The Lost World, Indiana Jones (and notably, Cook would also later design

The Adventures of Indiana Jones Role-Playing Game for TSR, Inc. in 1984), and the character of Jackson Elias in

Masks of Nyarlathotep, the genuinely classic campaign for

Call of Cthulhu. It has pulpy undertones which are just a little bit at odds with the cod-medievalism of traditional

Dungeons & Dragons—and certainly, of

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, First Edition.

The adventure takes place in the far south amidst a mountainous jungle region.

The Scarlet Brotherhood, a 1999 supplement for

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Second Edition, would later set the module in the mountains south of the Pelisso Swamp in Hepmonaland in the World of Greyhawk. The supplement would also identify the Forbidden City as Xuxuleito and place it in Xaro mountains and previously ruled by Batmen and Olman before the Yuan-ti as detailed in

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City. From this region come reports of bandits waylaying and attacking caravans, the few survivors from the ambushed merchants and guards letting slip tales of strange flora and dangerous fauna, but having no idea as to who took the goods or where. Certainly the goods have not appeared in the markets since, so the question is, where have they been taken and by whom? Further, since the goods included singular pieces of treasure, including books, scrolls, and other items, all of them identifiable and valuable, somewhere to the south, someone is sitting on a hoard of treasure. This has been enough to spur multiple parties of adventurers to venture south into the jungles, though again, little has been heard of them since. The latest band of adventurers to travel south in search of these riches are the Player Characters, who after a long and perilous journey, have reached a village home to native people who are both friendly and happy to share information about the dangers of the surrounding jungle. The village chief tells them of creatures called the Yuan-ti and their servants, the Tasloi, lamenting that they recently kidnapped his son before retreating back into the jungle. The village shaman also warns them about a ‘forbidden city’ that lies deep in the jungle, which the village inhabitants believe houses the ghosts of their dead enemies. In return for their rescuing his son, the village chief will provide guides to the entrances to the ‘Land of the Demon-men’, but will go no further.

From here, there are two stages to

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City. The first is getting into the city. The second is exploring the city. Five entrances to the city are described. Some are mere paragraphs, simple descriptions of how the Player Characters might use vines or a tall tree to climb or lower themselves down into the valley below, but two are detailed entrances into the valley. Both are long tunnels, mostly linear in nature, consisting of ten or so locations. Both are notoriously challenging, but for different reasons. The Forgotten Entrance is guarded by the Yuan-ti and their minions, the bugbears, and features two grand set pieces. One makes sense, the other does not. The encounter which makes sense is a great swinging or rope bridge across a chasm, guarded by Tasloi on an upper platform who will fling rocks down onto the Player Characters as they make their way across. The bridge is sturdy enough, but if it takes enough damage, it will splinter and fall, dropping everyone on it to the bottom of the chasm. This will inflict the maximum amount of dice rolled for falling damage—probably enough to kill most of the Player Characters. Despite this potentially total party killing—and thus scenario ending—outcome, this is a grand, pulpy encounter, much like the end of

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (though of course, that was not released until 1984).

The encounter which makes far less sense takes place in the Hall of Meditation. Here the Player Characters must get through a locked door in order to proceed on towards the city, but the key has been locked in a chest to prevent the Bugbear guards from simply deserting their post. In order to make even more difficult for the Bugbears to get hold of, the chest has been stuck upside down on the ceiling in an anti-gravity sphere, and is not only locked, but trapped with fear gas. Rungs on the ceiling enable the Bugbears, the Yuan-ti, or the Player Characters to swing out to the anti-gravity sphere and the chest. The intention is that if the trap is triggered and the saving throw failed against the fear gas, the Player Characters will run away, out of the anti-gravity sphere, and thus fall to the floor and take damage. Which is a clever trap, but it makes no sense in context as it simply blocks the Bugbears from attempting to warn their Yuan-ti masters against any intruders, such as the Player Characters. The whole encounter feels much more like an excerpt from a funhouse or death trap dungeon rather than a logical piece of design for this adventure. The encounter, and indeed, the whole tunnel entrance, is in fact, a holdover from the origins of

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City as a tournament module and can be better viewed as the next stage in a competitive event, presenting the Player Characters with a puzzle or thinking challenge rather than another combat encounter. The tournament origins are further emphasised by the fact that the chief’s son—whom the Player Characters have agreed to rescue—can be found outside the exit into the city at the far end of the forgotten entrance. In effect, the culmination of the tournament would be the Player Characters rescuing the chief’s son, thus marking their ultimate success.

The other tunnel entrance, the Main Entrance, does not lead to where the chief’s son is and is wilder in tone and in content, having fewer guards to encounter, but nevertheless still very dangerous. In fact, it is very dangerous from the start. The very first encounter in the Main Entrance tunnel will be with an Aboleth—the very first encounter with an Aboleth in

Dungeons & Dragons!—and it is a tough encounter. Worshipped by the Mongrelmen of the Forbidden City as a god, the Aboleth has four attacks that can inflict a disease which turns the victim’s skin membranous, inflicting further damage if not kept wet, and which takes a

Cure Disease spell to deal with. So the Player Characters need to have a Cleric or Druid who can cast Third Level spells amongst their number. Then, the Aboleth also has Psionics, which is a serious problem for the Player Characters if they do not have them. The other encounters in the Main Entrance tunnel are not necessarily as tough, but they are challenging, and when compared with the Forgotten Entrance, there is much more logic to them. One of the more entertaining encounters is with a Xorn who is not interested in attacking the Player Characters, but wants food—ideally precious metals—before it will let them pass. This presents a fun roleplaying challenge and a monster with much less of a lethal motivation.

Whatever route the Player Characters take into the city, what they discover is a set of vast ruins stretching across a steeply walled rift valley in the mountains, one part of it under a swamp. Just as the vista has opened up after the linear nature of the tunnels, so too, do the play options of

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City. Here is where the module’s inspiration of

Red Nails comes into play, although Dashiell Hammett’s novel

Red Harvest, Akira Kurosawa’s

Yojimbo, and Sergio Leone’s

A Fistful of Dollars, all have similar set-ups. The Forbidden City is home to several factions—Bullywugs and their god, a Pan Lung dragon, the Tasloi and their Bugbear minions, and the Mongrelmen. At the heart of it is Horan, an evil Magic-User, who resides in a compound in the city almost like a Bond villain, and who has been manipulating the factions in an attempt to control them all and take power. Ultimately, it is Horan who is responsible for directing the attacks by the Yuan-ti.

Although there is no great metaplot or story line to

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City, the broad idea is that the Player Characters will set up camp in the city and begin investigating, dealing with the factions in turn, and ideally, either leading one or more against the others, or driving them to attack the others. Typically, this will be during the day when the city is quiet, whilst the Player Characters rest and hold up in their hopefully defensible base of operations when the inhabitants of the city are active at night. How the characters go about this is up to their players, and they could easily ignore this in favour of taking out the factions one-by-one. To support whatever course of action the players and their characters decide to take, locations are described for each of the city’s factions—the Bullywugs, the Tasloi, the Bugbears, and the Mongrelmen. Some of these are more detailed than others in terms of story and plot. For example, if the Mongrelmen capture the Player Characters, they are expected to select a champion from amongst their number and wrestle the Mongrelmen chieftain to the death, or go willingly as sacrifices to the Mongrelmen god. If the champion wins, he becomes the new Mongrelmen chieftain, and is expected to lead them, for all intents and purposes, a hostage. Amongst the Bugbears is Shruzgrap, a rebellious and deceitful young warrior, who wants to be chief of his tribe and who offer to make a deal with the Player Characters if they help him. Of course, if they do, he will betray them.

In addition,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City offers four backgrounds or reasons to use the Forbidden City in campaign play and four adventure ideas. The former include merchants hiring the Player Characters to investigate and put a stop to the raids as detailed in the background to the module, rescuing victims kidnapped from the surrounding lands, scouting and clearing the city ahead of an invasion, and recovering important papers stolen from a courier before other interested parties do. The adventure ideas include investigating the city’s sewer systems, home to jungle-ghouls, demonic leaders, and the fabulous, lost temple of Ranet; stopping a vile tentacular creature from another plane which the Yuan-ti have summoned and begun to worship from destroying the city; investigating and destroying a spy network which is organising the raids on the caravans—this idea will take the Player Characters out of the Forbidden City; and being thrown back in time to explore the city before its fall…

Rounding out

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City are the complete stats and writeups of the new monsters presented in its pages—the Aboleth, the Mongrelmen, the Tasloi, and the Yuan-ti. Also included are stats for the Pan Lung and the Yellow Musk Creeper from the Fiend Folio. Finally, there is a roster of ready-to-play Player Characters, the first six of these having been used in the original tournament of the module.

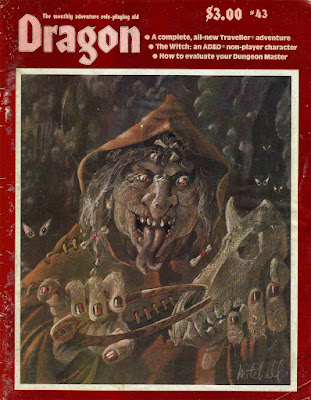

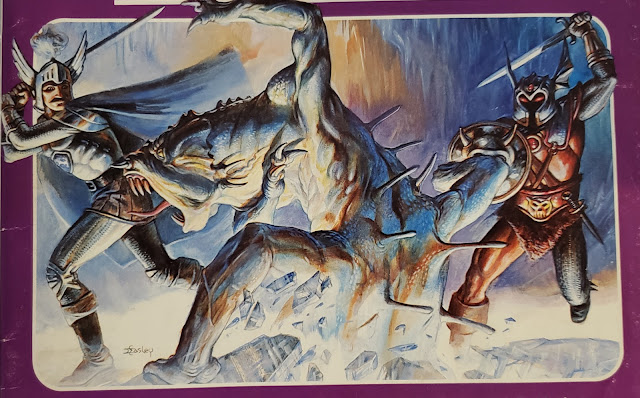

Physically,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is a mix of the good and the bad. Errol Otus’ front cover depicting a desperate fight between a Bullywug and Fighter with the Fighter in its clutches and drives his sword into its belly as a Gnome Wizard blasts another Bullywug in the background is superb. In fact, all of the artwork is excellent in the module. In general, the module is well written and presented, though some of the monster descriptions and stats are repeated in the main body of the text, and the individual maps of the locations in the city are nice and clear. However, the map of the city itself is difficult to read, despite it being a stunning piece.

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is a module with a huge number of problems. In terms of its most basic design, it has a split personality between the tournament play elements (with advice how to run the entrance tunnels as a tournament, but not the means, since the module is not part of the part of the ‘C’ or Competition series of scenarios) and the sandbox aspect once the Player Characters are in the Forbidden City. The former is highly detailed where the latter is not, the former has the players pushed in one direction, whereas the latter does not. Now whilst at least one of the encounters in the tunnels makes sense, the actual city is underwritten, with little description as to its current state or background as to its origins or who its original inhabitants were, with only the bases for each of the factions receiving any real attention or detail. And of those factions, the Yuan-ti suffer from the same issue. The module also treats its NPCs badly, few of them being named—even at the start the unnamed chieftain is not given the name of his son (when he is found, it is given as Zur), and few of the monstrous NPCs are named. So Shruzgrap the Bugbear is, as is the shaman who will secretly support him, but not the chieftain he wants to overthrow. Further, even the one named NPC in the scenario who will readily come to the Player Characters’ aid, an Elf Magic-User who is the only survivor from a previous expedition, has an unpleasant manner which will only serve to at least annoy the Player Characters, if not completely drive them off. Of course, none of her former companions are named.

Worse,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City ignores the primary reason for the Player Characters to travel as far south as the Forbidden City—the treasure from the caravans. It is completely omitted from the scenario, leaving a motivation to be unfulfilled. And without that, once the chieftain’s son has been rescued, there remains little motivation for the Player Characters to stay in the city. Now, there are plenty of potential motivations and adventure ideas given at the end of the module, but these are not used in the module as written despite the fact that they are infinitely more interesting than the very basic ones of searching for treasure (which does not exist) and rescuing the chieftain’s son given at the beginning of the module. As a consequence of their not being written into the module, there are no sewer systems filled with jungle-ghouls, no lost temple of Ranet, no temple to tentacular thing from another plane, no spy network, no travel back to explore the city in its prime, and so on.

The fact is,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is begging for all of these—and more. The module is begging for development, for the input of the Dungeon Master, and then the players and their characters. The scope for development and thus for storytelling and adventure in

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is huge, but like that potential, the tools to do so are all too often severely underwritten.

—oOo—

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City was extensively reviewed at the time of its release. Anders Swenson reviewed it in

Different Worlds Issue 16 (November 1981) and was in the main positive about the module, concluding that, “Overall, the module is a good buy – there is a lot of interesting text crammed into the pages, and most of it is useful right off.

The Forbidden City can be played as written, and if you want to jazz it up, so much the better.”

However, Gerry Klug, writing in ‘RP Gaming’ in

Ares Magazine, Number 12 (January 1982) was not as positive. He described

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City as being, “…[I]llconceived, disorganized and, in some places, so ridiculous as to make me think TSR has lost editorial control over their product.” before lamenting, “TSR has set a standard in the FRP-ing community which the rest try to keep up with. If Dwellers of the Forbidden City is any indication of what is coming, they may not live up to their own standards. E. Gary Gygax, where are you?” (With thanks to Luca Alexander Volpino for access to

Ares Magazine, Number 12.)

Writing in Open Box in

White Dwarf #40 (April, 1983), Jim Bambra gave

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City average scores for playability, enjoyment, skill, and complexity, before giving it an overall score of five out of ten, and said, “To give the module its due it does offer a mini-campaign setting and many ideas of how to expand it. Any DMs using it, however, are going to have to put in a lot of work to make it more than a series of encounters and you’re prepared to this you may as well design your own from scratch!”. He concluded by saying that “… I1 is just not worth considering.” (With thanks to Emma Marlow for access to

White Dwarf #40.)

More recently,

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City was included in ‘The 30 Greatest D&D Adventures of All Time’ in the ‘Dungeon Design Panel’ in

Dungeon #116 (November 2004). It was ranked at number thirteen with Eric L. Boyd describing it as classic adventure in which Cook created a “[L]ost city jungle in the great tradition of Edgar Rice Burroughs” and “The PCs can battle their way into the city through a labyrinth of traps and monsters or find their own way into the sprawling, jungle-cloaked ruins... Cook provides a host of backgrounds to motivate exploration of the city, but the map itself is inspiration enough.” Wolfgang Baur, editor of

Dungeon magazine, added, “This adventure may be best remembered for its monsters—it was from Forbidden City that D&D gained the Aboleth, the mongrel-man, the tasloi, and the yuan-ti. The aboleth that guarded one of the entrances to the city was worshipped by the local mongrelmen as a god.”(With thanks to Paul Baldwin for access to

Dungeon #113.)

—oOo—

Wolfgang Baur is right to suggest that the module is best remembered for its monsters. Of course, it is memorable for introducing the Aboleth, the Yuan-ti, and other monsters, but

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is neither a classic, nor does not deserve its revered status, and it certainly does not deserve to rate as high as thirteen on the list of greatest

Dungeons & Dragons adventures of all time by

Dungeon magazine for the thirtieth anniversary of the

Dungeons & Dragons. As written, it simply is not that good, its tournament versus sandbox style of play giving it a split personality and its sandbox elements severely underwritten and underdeveloped in far too many places for the Dungeon Master to bring to the table and make playable without undertaking a great deal of development work. Yet if she can, there is a fantastic adventure to be got out of

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City, the setting has both Lovecraftian and Pulp sensibilities—the Yuan-ti essentially being Robert E. Howard’s Serpent Men, and the factions, the plots, and the setting are all ripe for development, such that it could form the basis of its own sandbox mini-campaign. There is room aplenty in the Forbidden City for this and more, including the Dungeon Master adding factions and locations of her own, whether that is in caves along the wall of the valley, in or underneath the ruined buildings of the city, and even outside of the city. This suggests then that

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is ripe for another visitation and development, expanding upon what author David Cook began with, and notably, Wizards of the Coast would do this with

Tomb of Annihilation for

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, a campaign which would work in

S1 Tomb of Horrors as part of the Forbidden City.

Ultimately, if

I1 Dwellers of the Forbidden City is remembered as a classic for more than its monsters, it is not because of what is written on the page, but because of what the Dungeon Master did to make the adventure playable—and what she had to do to make it playable.

Articles

Articles