A decade ago, on January 12th, a plague struck the world. A flu-like plague which seemed resistant to the then available treatments. Fortunately nobody died, but eleven days later, on January 23rd, all of the symptoms vanished and everyone recovered. Only later did people realise the significance of what became known as ‘Ghost Flu’ as months later, sufferers began exhibiting powers and abilities only found in mankind’s wildest imaginings and biggest cinema screen franchise. The ability to fly, phase through walls, read the minds of others, control gravity, flatten or enhance the emotions of others, and read or even enter dreams. Literally, people had superpowers. This manifestation becomes known as the ‘Sudden Mutation Event’ or ‘SME’, and in the next ten years approximately one percent of the population will manifest SME. In response, there was no rash of costumed heroes or villains, though a few tried. The most photogenic of SME suffers became celebrities, sportsmen, television and film stars, or politicians, others found jobs related to their newly gained powers, for example, a firefighter who control flames or oxygen, a transmuter who could literally turn lead into (industrial) gold, or a healer who work as a medic or doctor, and the most popular sports found ways of incorporating them into their play. Some though turned to crime, and of course, there were criminals who exhibited SME, and whilst the Heightened as they became known were mostly assimilated into society, they could still be victims of crime and they were also victims of a prejudice all their very own. For example, the Neutral Parity League campaigns against ‘Chromes’ (from ‘Chromosome’) as the Heightened are nicknamed, often violently, whilst organisations like the Heightened Information Alliance campaigns for the protection of their rights. In general, the Heightened have become one of society’s accepted minorities and most just get on with their lives.

When one of the Heightened is involved in crime—whether as victim or perpetrator—the police will investigate and handle the matter just as they would any other crime. However, most big city police forces have established a unit to specifically deal with such cases. This is the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit (HCIU), staffed by Heightened members of the police force and tasked with investigating and solving SME related crimes, whether committed by or against SME sufferers. The HCIU also serves as a combination liaison/bulwark between the mutants and ordinary folk. The law has also adapted to take account of the prevalence of Heightened abilities. Thus investigative powers such as Observe Dreams and Read Minds require consent or a legal warrant, the use of X-Ray Vision ability must follow strict health and safety guidelines as its emits radiation and can cause cancer, the wrongful use of Impersonate is fraud, and several powers, including Radiation Projection, Invisibility, and Read Minds are deemed inherently dangerous. Such powers fall under Article 18 which regulates their use and may even see their users being monitored. The study of superpowers and SME expressives is known as Anamorphology, while members of the HCIU are trained in Forensic Anamorphology.

This is the set-up for

Mutant City Blues, a super powered investigative roleplaying game, originally designed by Robin D. Laws and published by Pelgrane Press in 2009. It uses the author and publisher’s

GUMSHOE System, designed to play investigative games which emphasise the interpretation of clues rather than their discovery, and which has been used with another genre in a number of roleplaying games from the publisher, including horror in

The Esoterrorists, cosmic horror in

Trail of Cthulhu, space opera in

Ashen Stars, and time travel in

Timewatch. In

Mutant City Blues the other genre is the classic police procedural of

Law & Order,

Hill Street Blues, and

NYPD Blue. The combination though is specific. The Player Characters are police officers with powers, not superheroes who are cops. So not DC Comics’

Gotham Central or the Special Crimes Unit from Superman’s hometown, Metropolis, or indeed, Wildstorm’s

Top 10. This is very much not a ‘Four Colour’ superheroes setting. The action and the investigation of

Mutant City Blues also takes place in a real city, whether New York or Toronto, or a city the Game Moderator is familiar with. Although

Mutant City Blues has the feel of a setting that is North America, it would be easy to set a campaign elsewhere, and there are notes on adapting it to the United Kingdom.

To help the Game Moderator adapt

Mutant City Blues to the city of her choice, the roleplaying game comes with a number of elements which mapped onto that city. This includes a future timeline which runs from the outbreak of Ghost Flu to the present day, a guide to the future city’s politics and leading figures, as well as its new institutes and businesses. First and foremost amongst them is The Quade Institute, the world’s foremost Anamorphological research centre, run by the renowned geneticist, Lucius Quade. The Quade Institute is also where members of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit are trained in Forensic Anamorphology. A complete Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit is described, ready for the Player Characters to be slotted into. Lastly, there is a ready-to-play scenario, ‘Food Chain’, which introduces the history of the

Mutant City Blues setting as well as providing a case for the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit to investigate.

In actuality that is the set-up for

Mutant City Blues as published in 2009. In 2020, P

elgrane Press published a second edition, this time by Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan and Robin D. Laws.

Mutant City Blues still retains the same set-up and flexibility in terms of where it can be set, but it also introduces a number of changes, not least of which is a new scenario, ‘Blue on Blue’. The majority of these changes have been implemented to make the game faster and easier to both set up and play.

As with other

GUMSHOE System games, Player Characters in

Mutant City Blues are defined by various abilities, either Investigative or General. Investigative Abilities are further divided into Academic, Interpersonal, and Technical. As a superhero roleplaying game, Player Characters in

Mutant City Blues also have superpowers or Mutant Powers, which are again split between Investigative and General Powers. What defines the split between Investigative and General Abilities and Powers is how they are used. In the first edition of

Mutant City Blues both Investigative and General abilities are represented by ratings or pool of points. For Investigative abilities, if the Player Character has the ability, he can always use it to gain core clues during an investigation, and his player could always spend more points from the Investigative ability pool to gain more information. For General abilities, such as Health, Infiltration, and Preparedness, a player expends points from the relevant pool and uses them as a modifier to a die roll to beat a particular difficulty. This is on a six-sided die and a typical difficulty is four, but can go as high as four. In the second edition of

Mutant City Blues, a Player Character still has pools of points for his General abilities, including mutant powers, but not for Investigative abilities and powers. Instead of ratings, a Player Character either has the Investigative ability or power, or he does not. During an investigation, a Player Character will always pick up a clue related to an Investigative ability. If a Player Character wants more information, he can Push.

The Push is the major rule change in the second edition of

Mutant City Blues. Replacing ratings for Investigative abilities, a Push is primarily used to gain more information or overcome obstacles preventing progress in an investigation. For example, it might be used to speed up the investigative process, such as getting the results back from the laboratory quicker than usual for Forensic Anthropology or Ballistics, to add an expert in the field as a friend using Art History or Occult Studies, or even use Cop Talk to impress the media or a Player Character’s superiors. A Push can also be used to sidestep or lower the difficulty of a General ability test. However a Push is used, a player only has two to expend per session, and they cannot be saved between sessions.

To create a member of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit, a player receives three pools of points to spend on his character. These are standard for both General abilities and Mutant Powers, but will vary for Investigative abilities, the value depending upon the number of players. To ease the creation process, the second edition of

Mutant City Blues includes templates that model particular police departments, such as the Forensic Science Division, Gang and Narcotic, Robbery, and Special Weapons & Training. Each template has a cost in points, with any excess being used to purchase other Investigative abilities and purchase and increase General abilities.

Whilst choosing Investigative and General abilities is relatively straightforward, selecting Investigative and General Powers is more involved. In standard superhero roleplaying games, a player is free to choose what powers he likes, in any combination, often to model particular superheroes from the comic books and films. Now that option is possible in

Mutant City Blues, but that diverges from

Mutant City Blues as written. Mutant powers in

Mutant City Blues are clustered together genetically, so that if a Heightened has the Transmutation power, he is also likely to have the Disintegration, Phase, Touch, Reduce Temperature, and Ice Blast powers. He may also have the Wind Control, Healing, Radiation Projection, and Self-Detonation powers, but not Pain Immunity or Gravity Control. All this is mapped out on the Quade Diagram—as devised by the renowned geneticist, Lucius Quade of The Quade Institute—and in addition to using it to select powers during the character creation, the Quade Diagram serves as a forensic tool in the game. HCIU officers can use it to determine the powers used at a crime scene, as many of them leave some form of residue. It can determine the involvement of one Mutant if the residue is clustered, more if there are several clusters. The point here is that mutant powers are known quantities and do not vary, and in addition, where in the comics, a superhero will often tweak or adjust his powers from one issue to the next, this is very difficult to do in

Mutant City Blues.

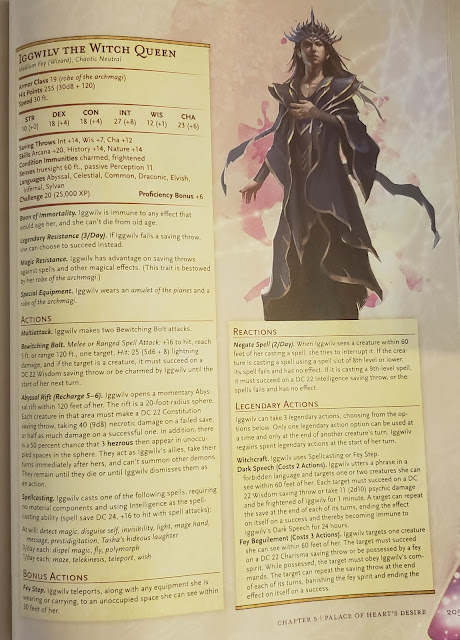

Our sample member of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit is newly appointed Grace Bruckner who transferred across from Robbery where she specialised in art theft. She has become adept at identifying forgeries from merely touch alone. Her tendency towards Disassociation means she has few friends on the force, her colleagues seeing her as cold and unfriendly. This is despite the fact they know her genetics.

Detective Grace Bruckner, 1st Grade

General Abilities: Athletics 4, Composure 10, Driving 2, Filch 2, Health 10, Infiltration 4, Mechanics 2, Preparedness 5, Scuffling 5, Sense Trouble 5, Shooting 4, Surveillance 6

Investigative Abilities: Architecture, Art History, Bureaucracy, Bullshit Detector, Charm, Document Analysis, Evidence Collection, Fingerprinting, Forensic Accounting, Forensic Anthropology, Languages, Law, Negotiation, Photography, Research, Streetwise

Investigative Powers: Touch

General Powers: Disintegration 1, Healing 3, Phase 5, Transmutation 3

Defects: Disassociation

Certain powers and clusters, however, also have ‘Genetic Risk Factors’ associated with them. For example, Heightened with the Night Vision and Thermal Vision powers have tendency for Watcher Syndrome, whilst those with Telekinesis and Force Field, suffer from Sensory Overload. As she has both Phase and Disintegration, Detective Grace Bruckner can suffer from Disassociation, which means that she has a tendency to emotionally withdraw from people, and if the condition worsens, to see the world and her actions as unreal. Genetic Risk Factors need not come into play though, but it all depends upon the mode in which the gaming group has decided to play

Mutant City Blues. The roleplaying game has two modes. In Safety Mode, Genetic Risk Factors are seen as potential risks to the Player Characters and may occasionally be topics of conversation, but in the main do not enter play except when they might affect Heightened criminals. In Gritty Mode, Genetic Risk Factors can express themselves in the members of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit, and in play, are one source of Subplots.

Subplots are plots extra to the main investigation, the ‘B’ plot to the ‘A’ plot, and are typically personal or tied to another case. The players are encouraged to suggest them and the Game Moderator can add them, but in Gritty Mode they can also take the form of a personal Crisis which will affect a particular Player Character, and they can be triggered by the expression of a Genetic Risk Factor or an event which occurs in the line of duty. The latter can affect all police officers, not just members of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit, but those triggered by a Genetic Risk Factor is specific to the Heightened. Mechanically, a Crisis requires a test and if failed, earns the Player Character a Stress Card. Similarly, if a Player Character exhausts the points from a power, but manages to refresh it by testing his Genetic Risk Factor (done against its resistance ability, which is different for each Genetic Risk Factor), he also gains a Stress Card due to the strain.

Mutant City Blues lists over fifty, each with a tag like Addiction or Home Life, and Deactivation or Discard conditions, these being ways a Player Character effectively forestall the effects of a Stress Card or get rid of it completely. Should a Player Character acquire three or Stress Cards, then he is forced to quit or is fired from the force due to stress and his consequent actions.

Crises and Stress Cards are obviously storytelling and roleplaying tools, but they are also ways of enforcing the conventions of

Mutant City Blues’ genre. In effect, Crises and Stress Cards are a way of handling a Player Character’s story arc over the course of a campaign. Just as in the television shows which inspire it, characters in

Mutant City Blues leave, resign, take a new assignment, or are killed. Similarly, the use of the two modes—Safe and Gritty—model the two types of police procedural. Safe Mode represents a police procedural which focuses on the powers and the cases, and less on the personal and home lives of the Player Characters, whereas the grimmer Gritty Mode brings into play the personal and home lives of the Player Characters as well as the dangers of using their mutant powers. Of the two, the Gritty Mode more strongly enforces its genre than the Safe Mode. And this is in addition to the grind of dealing with the bureaucracy of the job, the Player Characters’ superiors, the media, and the criminals.

The two genres for

Mutant City Blues—police procedural and superheroes—will be familiar to most, but not necessarily together. The roleplaying game’s authors provide plenty of advice to that end. The rules and advice cover collecting clues and using Pushes and their benefits, action at non-lethal, lethal, and superpowered levels, including combat, shootouts, chases, and more. There is a lengthy discussion of how the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit operates, including an orientation manual (with annotations from a member giving an explanation and opinion on how things are actually done), handling interrogations and court scenes, how the presence of the Heightened has changed the law, and running cases of the week and big plots. Plus there is a guide to the future world of

Mutant City Blues, its politics, cultures, sports, and notable figures that the Game Moderator can map onto the city of her choice. Plus that mapping need not be onto a city in the near future, but could be the here and now, and there is advice for doing that too. The players are not left out here with advice on selecting their characters’ watch commander, using subplots, and suggesting some interview techniques, since after all, few of the players are going to be trained police officers. Lastly, there is an adventure, ‘Blue on Blue’ which does a good job of introducing the setting of

Mutant City Blues and its various elements as they are affected by the Heightened, and takes the story of SME all the way back to the beginning. That said, it very much has the feel of a North American city and the Game Moderator will need to make some adjustments to set it elsewhere.

Throughout the pages of

Mutant City Blues, there is another option discussed. That is instead of the Player Characters as members of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit, they are Private Investigators. This gives the players and their characters greater flexibility in terms of how they approach investigations, as well as less responsibility and also less authority. However, they are still private citizens and they will need to be equally as careful, if not more so, in their use of their powers than members of the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit. Rather than the set-up and organisation provided by the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit, the players and their characters will need to work out the details of their agency ahead of time. The scenario, ‘Blue on Blue’ does have notes to enable it to be run using private investigators, but it is really written to be played using Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit officers.

Physically, for a book published in 2020,

Mutant City Blues is surprisingly done in black and white. In some ways, that is thematic, and to be fair, it does not detract from the book in any way. In general, the artwork is excellent, the book is well written, and the layout clean and tidy, and best of all, easy to read.

If there are any issues with

Mutant City Blues, it is in tone and setting. Some players may well find its strongly implied setting to be too North American, but the police procedural is very much a North American television staple, which for others it is that its superpowers are too low powered, to be not quite Four Colour enough. Yet even the roleplaying game’s Safe Mode is not Four Colour, although it is much closer than Gritty Mode, and after all, it is written to be a police procedural with superpowers, rather than it is a superpowered police procedural.

The

GUMSHOE System was always designed to ease the process of playing investigative roleplaying games, but its iteration here in the second edition of

Mutant City Blues has gone even further, switching from the previous edition’s pools of points to a simple binary yes/no for its Investigative abilities. Combined with the equally as simple Push mechanics and

Mutant City Bluesmakes investigations even easier, shifting any prior complexity to the game’s action when General abilities—mundane and mutant come into play. And really, they are not that complex.

Inspired by two genres—police procedural and superheroes—

Mutant City Blues still remains underpowered for handling either separately, but merged together, the result is an appealing combination of familiar genres that are consequently easy to roleplay. And that is made even easier by the streamlining of the

GUMSHOE System and the cleaner presentation in this new edition.

Mutant City Blues does what it says on the badge, present police procedural and investigative roleplaying in a near future that is almost like our own world, and make it accessible and engaging. The combination is very specific, but there can be no doubt that

Mutant City Blues does it very well.

For Free RPG Day 2021, Modiphius Entertainment released not one, but three titles, two for existing roleplaying games, one for a forthcoming title. The first for the existing roleplaying game the Star Trek: Adventures Quick-Start, an introduction to Star Trek Adventures, the tenth roleplaying game to be licensed or at least derived from that Science Fiction intellectual property. As with other quick-starts, it provides an explanation of the rules, a complete adventure, and six ready-to-play Player Characters. All of which comes in a full colour—or is that full black?—thematically perfect LCARS pastel shades and layout on deep black, with the pre-generated Player Characters presented on a white background for easy printing. All the Game Master has to do is find some tokens, some twenty-sided dice, and some six-sided dice, and she has everything she needs to run the adventure in the Star Trek Adventures Quick-Start.

For Free RPG Day 2021, Modiphius Entertainment released not one, but three titles, two for existing roleplaying games, one for a forthcoming title. The first for the existing roleplaying game the Star Trek: Adventures Quick-Start, an introduction to Star Trek Adventures, the tenth roleplaying game to be licensed or at least derived from that Science Fiction intellectual property. As with other quick-starts, it provides an explanation of the rules, a complete adventure, and six ready-to-play Player Characters. All of which comes in a full colour—or is that full black?—thematically perfect LCARS pastel shades and layout on deep black, with the pre-generated Player Characters presented on a white background for easy printing. All the Game Master has to do is find some tokens, some twenty-sided dice, and some six-sided dice, and she has everything she needs to run the adventure in the Star Trek Adventures Quick-Start.