A Holiday Horror Quartet

Imagine growing up in Lovecraft Country? What sights and hints of the Cthulhu Mythos might the children of that benighted corner of New England been exposed to, growing up as they have in or near its darker and more mystical corners—Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport? Since being coined by the late Keith Herber, the setting has been more widely explored in supplements for Call of Cthulhu, such as Arkham Unveiled and Tales of the Miskatonic Valley during the nineties, and relatively recently in New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley and More Adventures in Arkham Country in the noughties. The point of view for all of these is always that of the Investigator core to Call of Cthulhu, but the very latest campaign to explore the region does so from the point of view of children, who perhaps suspect that the world around them is perhaps a little stranger than some of the adults around them would know or even admit, and in investigating that strangeness, may lay groundwork for their becoming fully fledged Investigators as adults. This is the set-up for The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection, a campaign which takes place over the course of a single year in New England, at four family get togethers, that will see cousins come together to discover dark secrets about their family and truths about the world around them, and confront mysteries and the Mythos, wonders and magic, horrors and truth, ultimately to form friendships which will last long into adulthood.

Imagine growing up in Lovecraft Country? What sights and hints of the Cthulhu Mythos might the children of that benighted corner of New England been exposed to, growing up as they have in or near its darker and more mystical corners—Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport? Since being coined by the late Keith Herber, the setting has been more widely explored in supplements for Call of Cthulhu, such as Arkham Unveiled and Tales of the Miskatonic Valley during the nineties, and relatively recently in New Tales of the Miskatonic Valley and More Adventures in Arkham Country in the noughties. The point of view for all of these is always that of the Investigator core to Call of Cthulhu, but the very latest campaign to explore the region does so from the point of view of children, who perhaps suspect that the world around them is perhaps a little stranger than some of the adults around them would know or even admit, and in investigating that strangeness, may lay groundwork for their becoming fully fledged Investigators as adults. This is the set-up for The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection, a campaign which takes place over the course of a single year in New England, at four family get togethers, that will see cousins come together to discover dark secrets about their family and truths about the world around them, and confront mysteries and the Mythos, wonders and magic, horrors and truth, ultimately to form friendships which will last long into adulthood.The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection from Golden Goblin Press, best known for titles such as An Inner Darkness: Fighting for Justice Against Eldritch Horrors and Our Own Inhumanity, The 7th Edition Guide to Cthulhu Invictus: Cosmic Horror Roleplaying in Ancient Rome, and Tales of the Crescent City: Adventures in Jazz Era New Orleans. Published following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it is a campaign for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, which is set in New England in 1925 and 1926 and which requires the players to take the roles of six eleven-, twelve-, and thirteen-year-old children. They each live and have relatives in the towns of Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport, and during the course of the year will spend Halloween in Dunwich, Christmas in Kingsport, Easter in Arkham, and Independence day in Innsmouth. The campaign consists of ‘Halloween in Dunwich’, ‘Christmas in Kingsport’, ‘Easter in Arkham’, and ‘Innsmouth Independence Day’. Of the four lengthy scenarios, the first two are not new. ‘Halloween in Dunwich’ originally appeared in the Miskatonic University Library Association monograph, Halloween Horror, one of the winners of Chaosium, Inc.’s 2005 Halloween Adventure contest, whilst its sequel, ‘Christmas in Kingsport’ appeared in the 2006 eponymous Miskatonic University Library Association monograph, Christmas in Kingsport, following Chaosium, Inc.’s Holiday Season Adventure Contest. For the Keeper who has access to them, the following supplements will be useful in adding colour and detail to each of the four scenarios in The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection. These are Return to Dunwich, Kingsport: The City In The Mists, Arkham Unveiled, and Escape from Innsmouth, as well as Miskatonic University, but whilst they can be a source of colour and detail, none of them are necessary to run the scenarios in the campaign.

Interest in combining horror and playing children in roleplaying games has picked up in the last decade, with television series like Stranger Things and roleplaying games like Kids on Bikes and Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the '80s That Never Was. For Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, scenarios like The Dare and The Haunted Clubhouse have explored the more modern periods, but The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection predates them all—not only in the genesis of the four scenarios in the anthology, but also in the period they are set. Further, as much as the players are called upon to roleplay children in the campaign, they will be confronted with elements of the Cthulhu Mythos and cosmic horror as well as horrific elements of the mundane world, including racism, prejudice, child abuse, bullying, and worse. Whilst none of these elements are specifically aimed at the Investigators the players will be roleplaying, they are present in several of the scenarios and they are likely to witness them. Consequently, many of the scenarios do carry warnings and both they and the pre-generated Investigators are designed to be played by mature players.

The six pre-generated Investigators consist of Donald Sutton, Gertrude ‘Gerdie’ Constance Pope, Gordon Brewster, Edward Derby, George Weedon, and Alice Sanders. Donald Sutton, the son of Kingsport artists and gallery owners, is a sensitive artist who is also friends with a ghost; Gertrude ‘Gerdie’ Constance Pope is from Dunwich and has strange white hair and ice blue eyes and has the gift of knowing things she should not, but does not know who her parents are; Gordon Brewster is also from Dunwich, a sturdy and hardworking farm boy who knows that the local hills are home to strange things; the studious and intelligent Edward Derby lives just off campus from Miskatonic University in Arkham, and has managed to read the strange books his father left him; George Weedon, also from Arkham, is athletic and principled; and the oldest cousin, Alice Sanders is a resident of Innsmouth, sturdy and stocky, but with keen mind and a slightly devious streak. All six are given full Investigator sheets and more—the more of which comes at the end of the book.

The campaign opens with ‘Halloween in Dunwich’. As members of the extended Morgan family, the cousins and their parents or guardians are invited to spend Halloween at the farm of the family patriarch, Great-Grandpa Silas. As the adults gather and catch up with the family gossip and rumours—some of which the Investigators have an opportunity to overhear and presages plots and events to come in the rest of the campaign’s scenarios—Great-Grandpa Silas takes the children away for a day of activities, games, and competitions. These include apple picking, pumpkin harvesting and carving, singalongs, and more, ending with a family feast and ghost tales round the fire. These activities serve functions in and out of the game. They get the Investigators to interact with each other and with their family, to begin forging relationships with each other in play rather than simply as written. They also serve to get the players rolling dice and have their Investigators be active and gain Experience Checks so that they are more skilled as the campaign progresses, and they also show how children’s lives can be fun, especially in a period where the fun was not so technologically sophisticated to what it is today. This is a device which the author pulls again and again as the campaign progresses, but each time the setting is different, the family dynamics are different, and the activities are different.

The activities also establish a very nicely balanced contrast between the mundane and the Mythos, again a device which will be used in all four scenarios. Of course, when it comes, the Mythos is no less horrifying than you would expect. One of the old family ghost stories told round the fire proves to have more than a ring of truth to it as a vengeful spirit returns from the family’s past to enact a ghastly plan. The adolescent Investigators are the only ones capable of defending their family against the predations of this spirit, and must fight through a swarm of Halloween-themed threats to confront the evil spirit and put an end to its dread ambitions.

If the Investigators looked forward to spending time with Great-Grandpa Silas in Dunwich, they are resigned to spending ‘Christmas in Kingsport’ at the home of their joyless Great Aunt Nora. She expects children to be ‘seen and not heard’, so there is little likelihood of any laughter or fun. Fortunately, Aunt Nora’s ward, the Investigators’ beloved older cousin Melba, a carefree flapper and black sheep of the family, comes to their rescue. She sneaks them out of the house and takes them on a guided tour of Kingsport—sledding, visiting friends, feeding cats, snowball fights, and more. There is something delightfully picaresque about this day out and despite her reputation as the black sheep of the family, Melba is a very positive character who likely reminds both the players and the Keeper of someone in their own family and childhood. Unfortunately, the joie de vivre of the cousins’ grand day out comes to a crashing halt when they are discovered and then the opprobrium heaped upon them and their cousin, Melba, is upstaged by the arrival of their uncle, who has returned from Europe with his new wife. Who is German, no less! Which all threatens to sour Christmas even more.

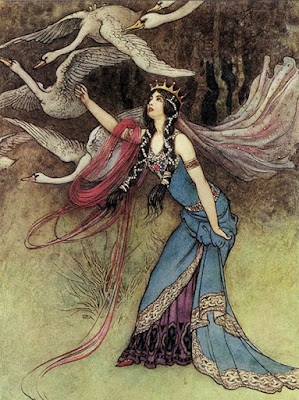

However, ‘Christmas in Kingsport’ takes a stranger and more wondrous turn when cousin Melba leads the Investigators Beyond the Walls of Sleep and into the Dreamlands. This strange realm of sleep and dreams has always been portrayed as strange and weird, but ‘Christmas in Kingsport’ focuses on the magic and the joy of exploring a mythical, almost Narnia-like, realm. Having made their day in the mundane world, Melba makes the Investigators’ sleep a magical holiday adventure, but it suddenly takes a scary turn when a party in their honour is literally crashed by Christmas demons! Captured, they must find out by whom and why, using clues they have learned in both the waking and the dreaming world—the Investigators will definitely need to listen, and hopefully solve the mystery before they wake up on Christmas morning. Ultimately, there is a great deal at stake in ‘Christmas in Kingsport’, but it is a wonderfully entertaining and thoroughly enjoyable scenario.

The third scenario, ‘Easter in Arkham’, is darker in tone and pulls the Investigators deeper into the Mythos and the secrets of Arkham. Staying at the homes of both Edward Derby and George Weedon, the Investigators have a lot of freedom to visit some of their favourite places in the town and get up to a lot. These include going to the cinema to see films such as The Thief of Bagdad or The Gold Rush, getting ice cream, visiting the penny arcade, bicycling, and more. Chief amongst these though, is attending and even participating in the Miskatonic University Easter Parade, there being opportunities for the Investigators to bake goods, paint Easter eggs, and make Easter bonnets, as well as enter their associated competitions. The pleasure of these activities is first interrupted by strange rumours of missing pets, evil lunch ladies, swarms of killer rats, and worse, and then fraught encounters with one of Edward Derby and George Weedon’s classmates playing truant and a horrid attack by one of the animals in the petting zoo at the Easter Parade. Investigation will reveal that recently departed pets have been returning to their owners, but changed, tainted, and unstable, which for Call of Cthulhu veterans can only point to one cause—and they would be right! However, the Investigators do not know that and getting to that cause will entail dealing with terribly afflicted animals, making friends with a gang of would-be members of the feared O’Bannion mob each of their own age, and negotiating with a figure out of witch-haunted Arkham’s past in a very nicely judged and staged encounter.

The fourth and last scenario in The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is ‘Innsmouth Independence Day’. Almost like the film Jaws, the Investigators get to spend and celebrate the Fourth of July on the New England coast, but this takes place on Haven Cove, an island opposite the harbour of Innsmouth, the most shunned and reviled towns in New England. This is a chance for the Innsmouth side of the Morgan family to meet the rest of the family, and vice versa, and do so on neutral ground, just sufficiently far away from the mildewed and mouldering seaport and its strangely inbred and evolving inhabitants, to gain the grudging acceptance of the High Council of the Esoteric Order of Dagon. However, one of the Investigators, Alice Sanders, a resident of Innsmouth has a plan. Once all of the competitions—swimming, sailing, fishing, sandcastle building, and more—are out of the way, she wants to sneak off the island and into Innsmouth and locate her family records. There are elements of The Shadow Over Innsmouth here, but the Investigators are sneaking in as well as sneaking out, and whilst there are plenty of watchful eyes who will alert the authorities to their presence, the Investigators can find allies too—and make friends. ‘Innsmouth Independence Day’ culminates in some quite nasty confrontations with some family secrets and truths, and whilst the protagonists are children, the scenario does not shy away from the sometimes brutal and inhuman way of life in Innsmouth.

Almost the last fifth of The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is dedicated to Investigators sheets for the six children at the heart of the campaign. This is fifty pages long, which is somewhat unnecessarily over the top given the size of the cast. However, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection does not just give Investigator sheets for the six children for the four scenarios in the campaign, but for later in their lives as well. The first set take the sextet into their early twenties, whilst the second presents them as Investigators for use with Pulp Cthulhu: Two-fisted Action and Adventure Against the Mythos. Hopefully, their inclusion will see the Investigators who have come of age and aware of the Mythos during the events of The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection return again to conduct further investigations.

In terms of staging the four scenarios in The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection, the Keeper will need to do some preparation. Primarily this will be to create the various adult members of the family in addition to those mentioned in the text. In terms of running the scenarios, the Keeper is encouraged to have his players spend Luck as needed on their Investigator’s tasks and actions, and in return be generous with restored Luck between adventures. In terms of staging the scenarios and the campaign there are, nevertheless, a number of issues with the campaign. First, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection really only works with the full six players. Second, the scenarios are linear in places, though this is offset by the fact that there is a lot for the Investigators to do throughout, both in the linear sequences and in the sequences where they have greater freedom of action. Third, the campaign negates the parents and guardians of the Investigators. They are named, but they are never really developed and it would have been useful if the Keeper had been given some roleplaying notes about both how to roleplay them and how each of them feels about the Investigators.

Physically, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is very well presented. In contrast to most releases for Call of Cthulhu, there is a sense of warmth to the book and a vibrancy to its illustrations. Many of these are taken from period festival illustrations of the day, whilst the illustrations of the Investigators have a suitably slight cartoonish feel to them that enhances the childhood sensibilities of the campaign. Not all of the illustrations quite match the text, but that is a minor issue.

As a piece of writing for a roleplaying game, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is simply an entertaining read. There are moments of tragedy and joy and outright humour in the writing and it is easy to see that the author is actually enjoying himself in writing the four scenarios in the campaign. As a campaign, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is linear in places and it does demand all six players, but it captures the feel of being a child again and pulls the players into roleplaying children again with all of its fun and disappointment and excitement and frustration of dealing with adults—and it does this without being patronising or belittling any one of them. It also brings alive a sense of family, with its gossip and secrets and difficulties. All of which will be familiar to so many players and Keepers from their own childhoods. As individual scenarios, The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection adeptly contrasts the mundane with the Mythos, whilst giving time for the Investigators to be children and revealing step by step some of the darker secrets about the world around them.

Golden Goblin Press has a well-deserved reputation for publishing excellent anthologies and campaigns for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, but The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is the exception. The Eldritch New England Holiday Collection is a superb piece of writing, which in capturing our childhoods and taking a new, fresh angle to Lovecraft Country, brings charm to Call of Cthulhu and Lovecraftian investigative roleplaying. The late, much missed Keith ‘Doc’ Herber would have been proud.