Zaharets, the Land of Risings, has been free for six generations. Kept as slaves for longer than they can remember, it has been one-hundred-and-fifty years since the Luathi rose up and overthrew the great kingdom of Barak Barad, driving out their masters, the monstrous bestial folk known as the Takan. The rebels anchored their claim to the region by founding cities at the northern and southern ends of the War Road, the route which runs along the coast. From the south came traders—in goods and information, from the Kingdom of Ger, whilst the Melkoni came from the west to establish a colony city-state of their own in the Zaharets. To the east, inland, lies a great desert, home to the horse clans of the Trauj, who trade with the Luathi and guide their merchants across the desert, whilst remaining ever watchful of dangers only they truly understand. In time, Zaharets has become a crossroads where three landmasses and numerous cultures meet. Yet as hard as the Luathi have worked to re-establish human civilisation, the Zaharets is not safe. There are a great many ruins to be explored and cleansed of the Takan, there are secrets of the time before the Luathi’s enslavement to be discovered, bandits prey upon the merchant caravans as they traverse the War Road, and there are dark forces which whisper promises of power and influence into the ears of the ambitious—and there is something worse. Jackals. Jackals give up the safety of community and law and order to go out into the ruins and discover the secrets hidden there, to burn the broken cities free of Takan presence, to face the bandits that raid lawful merchants, and worse… No good community would have truck with the Jackals. For who knows what evil, what chaos they might bring back with them? Yet Jackals face the dangers that the community cannot, Jackals keep the community safe when it cannot, and from amongst the Jackals come some of the mightiest heroes of the Zaharets, and perhaps in time, the community’s greatest leaders when the Jackals decide it is time to retire and let other Jackals face the dangers beyond the walls of the towns and cities of the Land of Risings.

This is the set-up for

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, a roleplaying game in land akin to the Levant in a post-Bronze Age collapse. Released by

Osprey Games, the publisher of roleplaying games such as

Paleomythic,

Romance of the Perilous Kingdoms,

Righteous Blood, Ruthless Blades, and

Those Dark Places, this is a roleplaying game inspired by the epic myth cycles of the Ancient Near East—

The Iliad,

The Odyssey,

Gilgamesh, amongst others, as well as the history. They primarily serve as inspiration though, for although there are parallels between the various cultures of

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, so the Ger are akin to the people of Middle/New Kingdom Egypt, the Luathi to those of Israel and Canaan, the Melkoni to Mycenaen Greece, and the Trauj to the dessert and tribal nomads of the Arabian Peninsula, these are cultural touchstones rather than direct adaptations. In

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, each of the Player Characters will be human, a Jackal from one these four cultures, most obviously a warrior or a ritualist, but also possibly a craftsman, scholar, thief, or even politician, who has eschewed his or her community in favour of secrets, glory, honour, and danger to ultimately protect it.

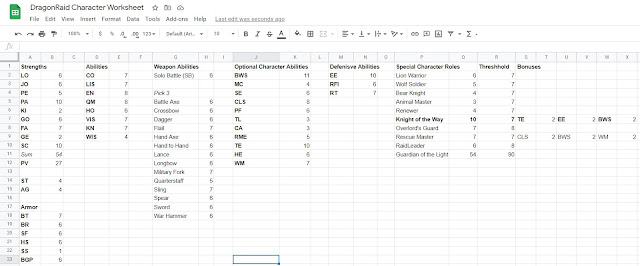

A Player Character or Jackal in

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is first defined by his Culture, either Luathi, Ger, Melkoni, or Trauj. This defines his virtues—what his culture values are, suggests reasons for becoming a Jackal, faith, magical traditions if a Ritualist, names and appearance, and skill bonuses. A virtue, if relevant, can be used to improve a skill test, essentially a fumble into a failure, a failure into a success, and a success into a critical success. For example, with ‘Fires of Freedom’, a Luathi Jackal can call on the virtue to defend against attempts—physical or spiritual—to take him into bondage or to fight to ensure that others remain free. A Jackal also has five attributes—Strength, Deftness, Vitality, Courage, and Wisdom—which range between nine and eighteen at start. They can be lowered at the cost of Corruption Points and a Ritualist also has a sixth attribute, Devotion, which represents the strength of his devotion to the spiritual world. He has various derived abilities, including Mettle, representing his willingness to fight; Clash Points, representing his battlefield awareness and capacity to react; and Devotion Points, used to invoke rituals, plus Skills which are percentiles and can go above one hundred percent. A Jackal has four traits, two general and two cultural. Each trait is tied to a specific skill and when that skill is rolled, a player can roll an extra die to provide with a choice of ones when determining the percentile value of the roll. This can be advantageous when determining if the player has rolled a critical result—failure of success, either of which requires doubles. So if Jackal had an appropriate trait, his player would roll percentile dice, plus an extra ones die, for example, ‘30’, ‘7’, and ‘3’, he would select the ‘3’ rather than the ‘7’ for a critical success of ‘33’ if the skill is high enough to get a critical success, or opt for the ‘7’ and ‘37’ if not to avoid a critical fumble. For example, ‘Light Touch’ is a general trait which provides this bonus for pickpocketing attempts for the Thievery skill rather than all Thievery related actions, whilst ‘The Jewels of Melkon’ is a Melkoni cultural trait which grants the extra die for Craft rolls related to whitesmithing, or working with gold or silver.

To create a Jackal, a player comes up with a concept, chooses a Culture and an associated virtue, before assigning seventeen points to his attributes (which begin at nine). After deriving various abilities from them, he assigns points to his skills. These are done group by group, so Common, Defensive, Martial, Knowledge, and Urban skills, and the points are different for each group, being derived from various attributes and derived abilities. The player selects four traits, two general and two cultural, selects equipment, and answers some character questions, primarily how and why he is a Jackal. The process is not overly complex, but it does involve a little arithmetic.

Kallistrate is a native of Kroryla, the Melkoni colony established four decades ago in the Zaharets. She is a devotee of Lykos, the founder of the colony and demi-god, and believes it is her destiny to follow in his path rather than that destined by her parents—a good marriage, children, and… boredom. She walked out on a betrothal and following in her family trade, weaving, and sort to make a name for herself in her own right.

Name: Kallistrate

Culture: Melkoni

Cultural Virtue: The Fires of Lust

Strength 12 Deftness 16 Vitality 12 Courage 12 Wisdom 10 Devotion 00

Clash Points: 5 (Max. 5)

Mettle: 12 (Max. 12)

Valour: 18 (Max. 18)

Wounds 6

Valour ×3 (6)

Valour ×2 (6)

Valour ×1 (6)

Common Skills

Craft 66%, Drive 15%, Influence 60%, Perception 55%, Perform 75%, Ride 10%, Sail 10%, Survival 50%

Defensive Skills

Dodge 60%, Endurance 45%, Willpower 45%

Martial Skills

Athletics 50%, Melee Combat 75%, Ranged Combat 30%, Unarmed Combat 40%

Knowledge Skills

Culture (own) 45%, Culture (Other) 25%, Healing 40%, Lore 20%, Ancient Lore 00%

Urban Skills 56

Deception 31%, Stealth 40%, Thievery 10%, Trade 45%

Traits and Talents

Bearer of the Eye of Chium (Perception for Ambushes)

Dangerous Beauty (Influence – Charm/Seduction)

Classically Trained (Rhetoric)

Twin Fangs (Two Leaf-Bladed Swords)

Combat

Damage Bonus: +1d4 Move: 15 Initiative: 16+1d6

Weapons: Twin Leaf-Bladed Swords (1d8)

Armour: Leather (2)

Mechanically,

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying employs the Clash system. This is a percentile system in which rolls of ninety-one and above is always a failure, even though skills can be modified or even raised through advancements above one hundred percent. Rolls of doubles rolls under a skill are a critical success and rolls of double over are a fumble. Opposed rolls are handled by both parties rolling, with the participant who rolls higher and succeeds at the skill check winning. In general, except in situations where there is an extended contest, such as a chase or combat, only one roll is made for a particular skill per scene. Of course, traits and cultural values have a chance of modifying a roll, depending upon the situation, but a Jackal also has several fate Points. These are used to gain a re-roll of a skill check or a damage roll, to add a narrative twist, to invoke a talent that a Jackal does not have, and to prevent a Jackal from dying when reduced to zero Wounds.

If in terms of skills and skill checks, the Clash system in

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is simple and straightforward, combat by comparison, is not. Every combatant typically one main action in a combat round, often a standard type attack, but with the addition of Clash points, combat becomes more dynamic, more heroic. In the main they work as reactions, such as responding to a melee attack and turning it into a clash or dodging a ranged attack, or taking minor actions in addition to a main action. For example, switching a weapon, invoking a rite, or standing up from prone. They can also be spent to improve the effect of an action, such as turning a simple attack into a power attack or sweeping arc, though this costs more in terms of Clash Points. Damage is taken first in terms of Valour Points, and then in Wounds, and once a Jackal begins suffering Wounds, damage can have permanent effects. Suffer enough wounds and a player has to roll for Scarring at the end of a combat.

On the edge of the Luasa Sands, Gashur, a Luathi Hasheer, a seeker of knowledge, has engaged a Trauj guide, Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan, to locate some ruins. Accompanied by her bodyguard, Kallistrate, they have penetrated a cave network and discovered some worked rooms where Gashur has begun to survey some of the mosaics on the walls. Their investigations have alerted a band of Takan, the small, foul and rat-like Norakan led by their leader, one of the hyena-like Oritakan and his lieutenant, the simian Mavakan. The Loremaster states that Kallistrate can use her Bearer of the Eye of Chium Talent to determine if she spots the ambush. Kallistrate has a Perception of 55% and her player rolls percentile dice plus another die for the ones. The percentile roll is ‘99%’! Not only a failure, but a fumble too. Fortunately, the roll of the second ones die results in a ‘5’. Kallistrate’s player choses the ‘5’ and turns the roll into a ‘95%’ rather than the ‘99%’, downgrading it from a fumble to a failure. It means that the three Jackals have been surprised as the Takan come charging into the room, the Mavakan at their head wielding its chipped bronze axe.

Barely able to squeeze through the doorway, the Mavakan runs straight at the nearest interloper, which is Gashur. It attacks first, and the Loremaster rolls ‘18’, opting for a Shield Bash manoeuvre, smashing into the Luathi Hasheer and knocking him flying into the rubble. From behind the Mavakan, the Norakan swarm into the room and over Gashur. If the other two Jackals cannot stop him, they will drag him back into the darkness… On the next round, Kallistrate wins the initiative—she is faster than anyone in the battle, followed by the Norakan and the Oritakan, then Ikeema, and lastly the Mavakan. Kallistrate charges the large beast readying her twin swords to strike. This grants her a total of six Clash Points to spend. Her player rolls ‘40’, enough for Kallistrate to hit with her Melee Combat skill, but her Twin Fangs Talent grants her a second ones die, and this rolls a ‘4’, which turns a success into a critical. However, the Takan have their own supply of Clash points—not as many as the Jackals, but enough—and the Loremaster decides that the Mavakan will spend one to turn Kallistrate’s melee attack into an actual clash. The Loremaster roll’s the Mavakan’s Combat value and it comes up a ‘99%’! Not only a failure, but a fumble, and since the Mavakan fumbled, it suffers maximum damage, ignoring armour, and Kallistrate gains a Fate Point. Since Kallistrate hit, her player decides to power up her attack by making it a Power Attack for two Clash Points. This increases damage by an extra six-sided die, so together with the damage for the weapon and Kallistrate’s damage bonus, the Mavakan suffers a total of eighteen damage. This is more than half of its wounds!

Ikeema uses a Clash Point to ready his bow and fire an arrow at the Oritakan, but misses as the Norakan drag away the helpless Gashur. The Oritakan responds with its ‘Commanding Presence’ special ability, its high-pitched barks driving the Takan band to follow its orders. The Mavakan regains five Wounds too and all of the Takan can adjust their combat rolls as if they had an appropriate trait! Kallistrate’s blow was mighty, but it looks like the battle is not yet going the Jackal’s way…Magic in

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying consists of Rites, its casters known as Ritualists. Each Ritualist enters into a pact with a power or entity of the spiritual realm, following one of the two ritualist traditions of his culture. For example, Luathi Ritualists are either Kahar, the Servants of Alwain, the creator of Kalypsis—greater world—and the initiator of Law, their rites focusing on purity, light, and water, or Hasheers of Ameena Noani, who seek out and gather the knowledge from before and during the kingdom of Barak Barad, their rites focusing on seeing and understanding. In terms of Jackal creation, a Ritualist selects a tradition from one of the two Ritualist traditions for his culture, receives one less general and one less cultural trait, knows the four rituals particular to his tradition, and has the Devotion attribute as well as access to the Magical Skills group.

In play, every Rite has a cost to cast or reserve—essentially to prepare it and cast when needed, a cost in Clash points to cast in combat, and so on. Each Rite is treated as a sperate skill roll, so it is possible to have critical effects and many can be advanced or upgraded. In the long term, this is necessary because

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying only includes four rites per tradition, so there are no extra rites for a Ritualist to learn, although it is possible to study another tradition, and even for non-Ritualists to begin studying a tradition.

Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan is of the Trauj people, a deaweller of the desert who keeps the traditions and magics of his people alive through storytelling. He has explored many ruins in his time and often serves as guide to those foolish enough from along the War Road who want to delve into the secrets that the sands of his homeland hide.

Name: Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan

Culture: Trauj

Cultural Virtue: Hearer of Old Tales

Ritualist Tradition: Yahtahmi

Strength 09 Deftness 12 Vitality 11 Courage 12 Wisdom 13 Devotion 15

Clash Points: 4 (Max. 4)

Mettle: 11 (Max. 11)

Valour: 15 (Max. 15)

Wounds 5

Valour ×3 (5)

Valour ×2 (5)

Valour ×1 (5)

Common Skills

Craft 45%, Drive 15%, Influence 20%, Perception 65%, Perform 57%, Ride 55%, Sail 10%, Survival 60%

Defensive Skills

Dodge 40%, Endurance 55%, Willpower 55%

Martial Skills

Athletics 50%, Melee Combat 35%, Ranged Combat 60%, Unarmed Combat 36%

Knowledge Skills

Culture (own) 50%, Culture (Other) 15%, Healing 30%, Lore 60%, Ancient Lore 00%

Urban Skills

Deception 40%, Stealth 45%, Thievery 10%, Trade 44%

Magic

Devotion Points: 15 (Max. 15)

Rites

Zahara Breaks the First Horse 52%

Ilou Slaughters the Eastern Beasts 52%

Yakhia Crosses the Luasa 52%

Tamat Finds the Well of the World 52%

Traits and Talents

Born Under Oura (Willpower)

Ruin Dweller (Lore for Ruins)

Combat

Damage Bonus: – Move: 14 Initiative: 12+1d6

Weapons – Scimitar (1d8), Trauj Bow (1d10)

Armour – Linen (1)

In the fight beneath the ruins, the Takan have spirited Gashur deeper into the darkness and the Mavakan has continued to press its attacks, wounding both Ikemma and Kallistrate. When it unleashes its Howling Fury, it forces a Willpower check on the two Jackals. Both fail, reducing their Valour temporarily. Fortunately, neither fail the second roll, so they are not forced to flee, but discretion being the better part of valour, they decide to retreat with the Mavakan at their heels. They race back through the corridors only to find their way blocked by a chasm—the Takan must have collapsed the bridge over it they used earlier. Kallistrate looks nervously at the distance, wondering if she can make the jump. Ikemma asks, “Tell me, have you heard how we Trauj first came to cross the desert? It was Yakhia who-” Kallistrate looks at the desert dweller incredulously and exclaims, “Is now a good time to be telling stories? We have Takan behind us and a missing employer.” The Yahtahmi laughs and replies that is always time for stories and in telling the story, casts the rite, ‘Yakhia Crosses the Luasa’ which grants them both a bonus to their Athletics skill equal to his Devotion for the rest of the day. With any luck, this will be enough that they can make the jump as they hear the roar of the Mavakan behind them.If

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is a solid design which supports heroic play and the clash of law and order, it is long term play where it begins to shine. In the long term, a player has the chance for his Jackal to push his skills above one hundred percent. This not only opens the option for a highly skilled warrior to divide his martial skills between attacks and dodge attempts and so forth, but further, they open up Advanced Skill Talents. These enable a Jackal to be heroic, even amazing, such as ‘Arrow Snatch’, with which a Jackal can enhance his ability to defend against a ranged attack by grabbing a missile from the air by spending further Clash points. Advanced Skill Talents are provided for each of the five skill groups.

The life of a Jackal is not just dangerous physically, but also mentally and socially. In facing the chaos left over from the remnants of the great kingdom of Barak Barad and the forces of chaos that would tear down the Law of Men, a Jackal can incur Corruption. It can also be incurred for corruptive actions, such as turning to banditry or allying with a chaotic being, and gain enough, a Jackal can have his Fate Points replaced by Dark Fate Points, which can be used to fuel dark rites, and also gain marks of Corruption, such as paranoia and pus-filled blisters. Corruption can also break a Jackal’s connection to the powers that grant him his rites, a major loss for any ritualist. Fortunately, a Jackal can undertake acts of Atonement, which varies from culture to culture, and though challenging, if successful, reduces the Jackal’s Corruption.

Unfortunately, as his Kleos, or renown, grows, a Jackal increasingly comes to the attention of the forces of Chaos. He will also gain recognition and potentially patrons, but the forces of Chaos will reach out to a Jackal, not necessarily to kill him, but tempt or coerce him—and if that fails, well, then kill him. He will have prophetic dreams too, their nature depending upon the Jackal’s degree of Corruption. Of course, no town or society, wants Jackals to return from their ventures with the stain of Corruption, and since Corruption cannot initially be detected, society cannot trust Jackals.

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is played over two seasons—rainy and dry, and at the end of each, a Jackal can undertake a Seasonal Action. One of these can be Atonement, but other options include Carouse, Craft/Commission an Item, Find Rumours, Increase Kleos, and Research. In the long term though, they also include Acquire Patron, Establish Home, and Hospitality, and these last Seasonal Actions represent not those of a Jackal excluded from society, but a Jackal who is attempting transition back into society. This will take years, but if a Jackal survives, he can retire, and the player’s new Jackal can benefit from the wisdom of the retiring one. Not necessarily covered in the roleplaying game, but there is scope here for generational play

a la King Arthur Pendragon.

For the Loremaster—as

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying terms the Game Master—there is a Gazetteer of the War Road, focusing upon Ameena Noani and Sentem, the Luathi cities at the northern and southern ends of the War Road, each of the various locations accompanied by a pair of secrets which the Loremaster can expand upon. A bestiary provides a range of threats, including wolves of the four-legged and two-legged (or bandit) kind, the dead, and Takan of various types. There is good advice on running the game too, but this is not a roleplaying game intended necessarily to be run by anyone new to the hobby. Lastly, there are three adventures, designed to start a

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying campaign and lead into

Jackals: Fall of the Children of Bronze, the first campaign for the game. The three scenarios will take the Jackals up and down the War Road.

Physically,

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is as well presented as you would expect for a title from Osprey Games. The artwork is excellent and the layout clean and tidy, but it needs a slight edit in places. It is far from poorly written, but it often suffers from a lack of examples in places, or rather a lack of full examples. It certainly could have done with a full example of a Player Character and a longer example of combat to show how the Clash system fully works. Another issue with the roleplaying game is that its tables—especially the combat tables—are not repeated at the rear of the book for easy access.

Conceptually,

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is easy to understand and grasp—the conflict between the Law of Men and Chaos, the tension between society needing those brave enough to face the threat of Chaos, but because they are, never trusted for it. Similarly, its Bronze Age will be familiar and easy to grasp, whether from

The Iliad,

The Odyssey, or

Gilgamesh, or the films of Ray Harryhausen, but as a setting,

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is not as easily accessible. This is a combination of content and presentation, there being a fair number of terms and phrases that the players will need to know to understand the cultures of the setting. Ultimately, the Loremaster will need to work a bit harder with her players for them to match the same degree of buy-in as herself.

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is a game which will reward long term play, so it is good to know that it will be followed by

Jackals: Fall of the Children of Bronze, but it would be nice to have an anthology of scenarios too. Overall,

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying nicely balances its tension between the Jackals and society, giving the Jackals a rich environment in which to explore, face ancient threats, be heroic, and ultimately return from to the society they turned away from in order to protect.

![]() Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.

Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.