City of Mist is a roleplaying game of neo-noir investigation and superhero-powered action. The intersection between the film noir and superhero genres has invariably derived from the Pulp fiction of the thirties and forties, with such characters as The Shadow or Batman, with generally low-key and low-powered heroes and villains in comparison to what would follow with the Four Colour subgenre.

City of Mist does something different. It brings in the powers and personalities of legends and gods of different Mythos—King Arthur, Red Riding Hood, Hercules, Athena, and Bast—and then obscures them. These powers and personalities manifest through Rifts, inhabitants of The City, a fog-shrouded, corrupt, and crime-ridden metropolis which could be Los Angeles of the thirties, New York of the fifties, or London of the sixties. It is simply known as The City. As Rifts, the Player Characters investigate Cases, and if necessary, fight crime, some of it committed by other Rifts, some not. Yet as powerful as each Rift is, the ordinary citizens of The City, the Sleepers, cannot see them for what they are and never see them manifest their powers. The Mist, a strange mystical veil renders each manifestation of a power or legend ordinary. Wallcrawling? Parkour. Lightning bolt? Broken electrical substation. Each Mythoi—god or legend or even abstract concept wants to manifest itself in The City, but the Mist works to prevent this, for the result might be chaos which could rip The City apart, so instead it allows them to manifest through the Rifts. Equally, as there is a tension between the Mythoi and the Mist, there is tension between the Mythos, both the legend which wants to become more and a mystery as to why it manifested, and the Logos, the ordinary self, safe and mundane in each Rift.

The

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is designed as an introduction to the setting. Published by

Son of Oak Game Studio LLC, it provides everything necessary to play through at least one Case. Designed to be played by five players and a Master of Ceremonies—as the Game Master is known—the starter set comes richly appointed. There are two books labelled ‘The Players’ and ‘The Master of Ceremonies’; five pre-generated character folios, one each for Baku, Detective Enkidu, Job, Lily Chow, Iron Hans, and Tlaloc; a deck of twenty Tracking cards and a Crew Card; two twenty-two by seventeen-inch poster maps; forty-one illustrated character tokens; and two

City of Mist dice—one purple Mythos die and one ivory Logos die. There is a lot on the box, all of it presented in full colour and illustrated throughout with artwork which invokes the two inspirations for

City of Mist.

The starting point for the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are five pre-generated Player Characters or Rifts. The quintet consists of Baku, Detective Enkidu, Job, Lily Chow and Iron Hans, and Tlaloc. Baku is a monster hunter, mythological Japanese chimera who hunts ghosts and devours nightmares; Detective Enkidu is an experienced police detective who hides a creature of the wild from Sumerian myth inside her which drives her to break the rules; Job is an unkillable priest whose family was killed by The City’s criminal underworld; Lily Chow is a runaway teen able to unleash Iron Hans, a magician-giant who is her companion, protector, and big brother; and Taloc is a small time crook with a gift of the gab and the power of the Aztec god of rain and water, thunder and lighting. Each of the five character folios is done on heavy, glossy card in A3-size. This does mean that there is quite a lot of information on each folio and that each folio takes up quite a bit of space on the table.

Unlike a traditional roleplaying game, a Rift is not described in terms of skills or attributes, but rather what he can do. Each of the five has the same set of Core Moves, or actions that they can attempt. What marks a Rifts out as special is the fact that he has four Themes, represented by four cards on the folio. They are divided between Mythos and Logos Themes, the legendary and the ordinary aspects of a Rift. Some Rifts have Mythos Themes than Logos Themes, and vice versa, and it is possible to lose Themes, so that a Mythos Theme might Fade and be replaced by a Logos Theme, whilst a Logos Theme might Crack and be replaced by a Mythos Theme. There are consequences to having Themes all of one type. For example, a Rift who replaces all of his Logos Themes with Mythos Themes, becomes an avatar of his Mythos, whilst losing his last Mythos Theme means he becomes a Sleeper and denies the existence of the Mythos. Whilst each Mythos Theme has a Mystery that the Rift wants to explore, and each Logos Theme has an Identity which represents a defining conviction, belief, or emotion, all Themes have Power Tags which can be invoked to help achieve a Rift’s intended goal, plus a Weakness.

For example, Tlaloc has the Mythos Theme ‘God of Rain and Lightning’. This has the Mystery, “Who Threatens to Blot Out the Fifth Sun?”, the Power Tags, ‘Call Upon the Storm’, ‘Thunderbolt Manipulation’, and ‘Electrifying Gaze’, plus the Weakness, ‘Indoor Spaces’. He also has the ‘A Dimond in the Rough’ Logos Theme, which as the Identity, “This Will Be The Last Time, I Swear!”, the Power Tags, ‘Good, deep down inside’, ‘Relentless Schmoozer’, and ‘Sticky Fingers’, as well as the Weakness, ‘Pangs of Remorse’.

Learning the game begins with ‘The Players’ booklet. It runs to forty-four pages and introduces the concepts behind roleplaying and

City of Mist, explains the character folios and how the roleplaying game is played—the ‘Moves’ or actions a Rift can take and their potential outcome, describes the various districts of The City, and provides a lengthy, eight page example of play. The latter includes two of the pre-generated Rifts in the starter set and showcases the various types of Moves that the Rifts can perform as part of an investigation and then combat scene. In general, the Moves are well explained, but do come with fine print and do require a little bit of study. The example of play though, is more than helpful in showing the prospective player and Master of Ceremonies how the game works.

Whilst the Master of Ceremonies has to read the ‘The Players’ book to understand the basics of

City of Mist, the ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book is all hers. This explains the role of the Master of Ceremonies, the Moves or actions she can take—and when, explains how to present challenges and dangers to the Rifts, and so on. A Danger encapsulates a threat to the Rifts, whether that is an NPC, a location, or a situation, which might be a crime lord’s chief enforcer, a car chase through the streets of The City, or a building on fire. The bulk of the ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book is given over to ‘Shark Tank’, the first case for ‘All-Seeing Eye Investigations’, the crew which the Rifts in the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are members of. ‘All-Seeing Eye Investigations’ has its own ‘Crew Theme card, complete with its own Mystery and Power Tags which the Rifts can invoke as part of their investigation.

Mechanically,

City of Mist and thus the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’, which means that it uses the rules first seen in Apocalypse World in 2010. These rules are player-facing in that the Master of Ceremonies does not make dice rolls, but rather that the player do. So from the Core Moves below, a player would roll ‘Convince’ to persuade an NPC, but ‘Face Danger’ to avoid being influenced. The rules in

City of Mist have eight Core Moves—‘Change The Game’ (give an advantage or remove a disadvantage), , ‘Face Danger’ (avoid harm or resist a malign influence), ‘Go Toe to Toe’ with someone, ‘Hit With All You’ve Got’ (harm someone in the worst way you can), ‘Investigate’, ‘Sneak Around’, and ‘Take the Risk’ (perform a feat of daring). When a Rift undertakes an action, his player states the Move he is using, applies any bonuses from Tags—short descriptors for a quality, resource, advantage, disadvantage, or object in the game—and applies the resulting Power value for the sum of positive and negative tags and statuses affecting an action, and rolls two six-sided (or the included

City of Mist dice) dice. A player can use all manner of Tag Combos to build up the Power value, as long as the Master of Ceremonies agrees. Several Tag Combos tailored to each pre-generated Rift are listed in their respective folios.

A result of a six or less is a Miss, a result of between seven and nine is a Hit, but with complications, whilst a result of ten or more is a Hit with a great success. Each Move works slightly differently and will give different results depending upon the roll. For example, the ‘Investigate’ Move gets a Rift answers to questions. If a Hit—seven or more—is rolled, the player can ask the Master of Ceremonies a number of questions and so gain a number of Clues equal to the Power value applied to the roll. If a Hit with complications—seven or more, but less than ten—is rolled, the Master of Ceremonies can expose the Rift to danger, give fuzzy, incomplete, or partly-true partly-false answers, or have the NPC ask the Rift a question, which he must answer. The aim in many Moves is to inflict a Status such as ‘Prone-2’ or ‘Befuddled-1’ or ‘Knife Wound-3’, which will give a Rift an advantage when rolling against that NPC who has suffered such a Status and a disadvantage when suffered by the Rift. A status like this is recorded on a Status card and kept in play until it is got rid of.

In addition, the Rifts can enter a Downtime sequence between the investigation or action, and undertake actions such as ‘Give Attention to a Logos’, ‘Work the Case’, ‘Explore Your Mythos’, ‘Prepare for your next Activity’, and ‘Recover for your next Activity’. This is handled as a montage scene and the effects of each action are automatic, whilst ‘Burning for a Hit’ grants an automatic success without complications, but also makes the Tag unusable until a Downtime sequence has been completed. Lastly, there is ‘Stop.Holding.Back.’, a special Move which enables a Rift to push his powers beyond their limit, though at the cost of a sacrifice to one of the Themes in a Rift’s folio.

The Master of Ceremonies has her own Moves, divided between Soft Moves and Hard Moves. A Soft Move is an imminent threat or challenge to the Rifts and their investigation, and really only consists of the Master of Ceremonies complicating things for the Rifts as a means to spur them into action. A Hard Move is a major complication or a significant setback to the Rifts and their investigation, and includes more options for the Master of Ceremonies. ‘Give a Status’ inflicts a Status on a Rift, but this can be resisted by a ‘Face Danger’ Move. Other Hard Moves, such as ‘Burn a Tag’, ‘Complicate Things, Big-time’, and others cannot be resisted and are more narrative effects and consequences than Moves as such. Essentially, they can come into play when a Rift fails to take an action or fails—rolls six or less—when undertaking an action. The Master of Ceremonies also has Intrusions, which really codify her using her judgement when adjudicating the rules.

The Case in the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set, ‘Shark Tank’ is organised in a couple of ways. First, it is a pyramid diagram of scenes, arranged by depth into a series of layers, which after the briefing, the Rifts can visit and investigate. Second, it is as a series of programmed steps which take the Master of Ceremonies and her players through the process of learning to play both

City of Mist and the scenario. For example, when the Rifts encounter a group of enforcers shaking down a shop owner, ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book says, “If this is the crew’s first fight, stop the story and move over to the players’ booklet, starting at Exhibit #8: Playing Through a Conflict on page 21 (see also MC Skill: Running a Fight Scene on the next page).” At which point, the players and Master of Ceremonies can set up and run the fight scene. However, this does not mean that the Master of Ceremonies can necessarily run ‘Shark Tank’ without any preparation, but it does mean that once prepared, she really has all of the references, pointers, and advice at her fingertips, including advice specific to each of the five Rifts which come pre-generated with the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set. The scenario itself has the Rifts interviewing the owners of several businesses on Miller’s Square where All-Seeing Eye Investigations has its shabby office, potentially exposing police corruption, confronting villains who bring a whole new meaning to the term ‘loan shark’, and having a showdown at the chief villain’s lair. Beyond the confines of ‘Shark Tank’, there are extra scenarios available which can be played using the content from the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set.

Also included in the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are two twenty-two by seventeen-inch poster maps and forty-one illustrated character tokens. The maps depict various locations which appear in the scenario, ‘Shark Tank’, and tokens cover all five Rifts and the various NPCs in the scenario. The single purple Mythos die and single ivory Logos die are decent twelve-sided dice marked with one through five twice, and then the domino mask symbol on the six face for the Logos die, and power icon on the six face for the Mystery die. Each icon also appears on the Themes in each folio.

Physically, the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is very nicely put together. The poster maps are on sturdy paper, the counters thick cardboard, the folios on glossy card stock, and both of ‘The Players’ and ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ booklets done on glossy paper stock. Inside, both booklets are superbly illustrated in a slightly cartoonish, but suitably film noir style, and their layout is excellent. Not only designed to look like a set of case files for a crime, but also designed to be accessible with effective use of devices to highlight text and boxed text for useful information. If there is a physical downside to the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set, it is the box it comes in. It is not particularly sturdy and unlikely to do a good job of protecting its otherwise excellent contents.

The

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is at first confusing. The box contains a lot of components and it is a little difficult to quite know where to start. However, once you dig into the rules in the ‘The Players’ booklet it begins to make a little sense, but really where it comes together is in ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ booklet, especially in the scenario, ‘Shark Tank’, which gives context for the rules and whether through nudges to the Master of Ceremonies to use particular rules or direct referral back to the rules in ‘The Players’ booklet. Once grasped, what the

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set reveals is a flexible ruleset which drives and pushes the narrative. The setting itself, combines urban fantasy with super heroics, but that combination avoids much of the trappings of the superhero genre. It shrouds them in the fog of the film noir genre just as The Mist masks The City from them. The

City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is an excellent introduction to The City and the ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ mechanics of

City of Mist.

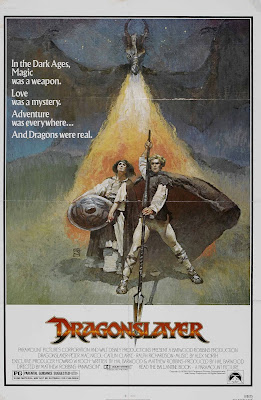

Since April is Monster Month here I thought it might be fun to check some monster-themed Sword & Sorcery & Cinema movies. Up first is a classic and premiered at the height of the 80s fantasy craze. Here is 1981's Dragonslayer from both Paramount and Disney.

Since April is Monster Month here I thought it might be fun to check some monster-themed Sword & Sorcery & Cinema movies. Up first is a classic and premiered at the height of the 80s fantasy craze. Here is 1981's Dragonslayer from both Paramount and Disney.