Feed aggregator

#FollowFriday and Kickstart Your Weekend: Zine Quest 3

One of the things I loved about small cons in the 80s (and really, those were the only ones I went too then) was the little indie Zines. Small, cheap (a bonus for a broke high school student) and packed with all sorts of strangeness, they had all sorts of appeal to me.

Granted they were not all good, but they had a sense of, I don't know, love about them. This was before Desk Top Publishing was even taking off yet so often these were Xeroxed, hand stapled affairs.

While it might be easier to get Zines out to the masses, the sense of love is still there.

This is why Zine Quest was made and now we are at the beginning of Zine Quest #3 over on Kickstarter and the choices are overwhelming.

There are plenty of OSR and D&D 5 choices as well as plenty of other indie games in the truest sense.

Trying to track them all is a bit more than I want to take on by myself. Thankfully there are good resources to help us all.

Hero Press / I'd Rather Be Killing Monsters

If you come here then you know "the other Tim" from across the pond. Hero Press is my go-to entertainment blog for all things RPG, Superhero, and more. Go there. No qualifiers, just go there. But he is also covering the Zine Quest projects he likes. You can also follow his Zine Quest tags.

Over on the Facebook side of things his group, I'd Rather Be Killing Monsters will be featuring even more Zines and project owners are encouraged to post links to theirs.

Gothridge Manor / RPG Zines

Tim Shorts (yes another Tim!) is also keeping everyone posted on Zines. He has been talking about them on his blog Gothridge Manor (also a great blog!) and his Facebook group RPG Zines. This is pretty much Zine central and worth your time to check out. Like Tim, Tim has a Zine tag for his blog as well.

But where Tim Shorts rises above the other Tims is his own contribution to the Zine project.

Be sure to back The Many Crypts of Lady Ingrade on Kickstarter.

Tenkar's Tavern

If you have been in the OSR any amount of time you likely know about Tenkar's Tavern blog/podcast/Facebook group. Tenkar is also covering Zine Quest with a lean to the OSR zines coming out.

You can also follow the #Zinequest3 hashtag on Twitter.

There are more launching every day in February, in fact, one launched while I was writing this post that I want to back. So expect a Part 2 next week!

Friday Filler: Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game

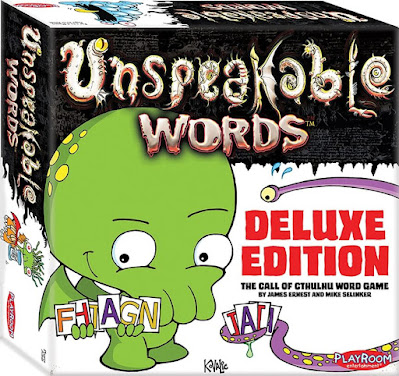

Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game is a word game with difference. Most word games require each player to spell out words and then score points based on things like their frequency of use or complexity of use. This game—originally published by Playroom Entertainment in 2007, and given a ‘Deluxe Edition’ in 2015 following a successful Kickstarter campaign, gives the word a Lovecraftian twist. In Unspeakable Words a player spells out words, perfectly ordinary and not at all Eldritch, but scores points based on the number of angles in the letters in the word so spelled. The first player to score a total of one hundred points wins. However, there is a catch. The more angles there are in a word spelled, the greater the likelihood of the Hounds of Tindalos using the angles to ease themselves out of time and so drive a player insane. Fortunately, this is only temporary, and a player can still continue spelling out words in an effort to win the game. If it happens five times though, a player is driven permanently insane and is out of the game.

Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game is a word game with difference. Most word games require each player to spell out words and then score points based on things like their frequency of use or complexity of use. This game—originally published by Playroom Entertainment in 2007, and given a ‘Deluxe Edition’ in 2015 following a successful Kickstarter campaign, gives the word a Lovecraftian twist. In Unspeakable Words a player spells out words, perfectly ordinary and not at all Eldritch, but scores points based on the number of angles in the letters in the word so spelled. The first player to score a total of one hundred points wins. However, there is a catch. The more angles there are in a word spelled, the greater the likelihood of the Hounds of Tindalos using the angles to ease themselves out of time and so drive a player insane. Fortunately, this is only temporary, and a player can still continue spelling out words in an effort to win the game. If it happens five times though, a player is driven permanently insane and is out of the game.And that pretty much sums up Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game, a card game designed for between two and eight players, for ages ten and up. Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game Deluxe Edition comes with one-hundred-and-forty-eight Letter Cards, a glow-in-the-dark twenty-sided die, forty Cthulhu Pawns in eight colours, a dice bag, and a four-page rules leaflet. The Cthulhu Pawns are cute, and serve as each player’s Sanity Points; the art is drawn by John Kovalic throughout, giving the game a consistently cute look; and every Letter Card is accorded a score for the number of angles in the letter and illustrated with a creature or entity of the Mythos. So ‘S is for Shub-Niggurath’ and scores no points because it has no angles, but ‘A is for Azathoth’ and scores a player five points because it has lots of angles!

On a turn, a player has seven cards with which to spell out a word. He cannot spell out proper nouns or abbreviations or acronyms, but he can spell out multiples. Once every player has accepted the word, the spelling player totals the value of its angles and attempts to save against their sanity-draining effect. This requires a roll equal to or over the value of angles on the game’s die. If the player succeeds, the word is accepted and its score added to the player’s running total. The player then refreshes his hand. Once a word has been accepted, it cannot be spelt out again by another player, though if it has a multiple, that could. Once used, that word cannot be spelled out again during the rest of the game.

If the spelling player fails his roll by rolling under the value of angles, the word is still kept, but the player loses a Cthulhu Pawn. Once he runs out of pawns, he is out of the game. At just one Cthulhu Pawn, a player can use his Letter Cards to spell out any word, no matter how weird or Eldritch it might be. The point is, is that with just the one Cthulhu Pawn, the player is disturbed enough to find any word acceptable even if others cannot.

And that really is it to Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game.

There are a couple of small quirks, though. The first is that the ‘Push Your Luck’ element of a player testing his Sanity means that a player must balance the need to gain the points from his word against the likelihood of failing the Sanity check! The second is that this balance will tip towards lower and lower word values as a player’s Sanity drops lower and lower. Then there is fun of being insane and being able to spell of almost any meaning the player wants from the Letter Cards in his hand. Which is even more fun if the player can define what the word actually means! Lastly, it is clear that the designers and artist John Kovalic have delved deep into the Lovecraftian mythos, for some of the cards are obscure, such as ‘Kaajh’Kaalbh’ and ‘R is for Rlim Shaikorth’, alongside the more obvious ‘C is for Cthulhu’ and ‘N is for Nyarlathotep’. The most knowing card is ‘H is for _____’. Or should that be ‘H is for _____’, ‘H is for _____’, ‘H is for _____’?

There are two downsides to Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game. One is player elimination, but fortunately, the game is short enough and since player elimination is likely to happen towards the end of the game, that no player is going to be out of the game for very long. The other is the price. Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game is relatively expensive for what is a short filler. That said, this is the deluxe version of the game and it looks very nice.

Unspeakable Words — The Call of Cthulhu Word Game Deluxe Edition is a solid, fun filler. Amusingly illustrated, it presents an entertaining, eldritch twist upon the spelling game that will be enjoyed by family and hobby gamers.

Star Trek: Mercy and BlackStar Characters

One thing I wanted to accomplish with the recent Character Creation Challenge was to create characters that I could use in my War of the Witch Queens campaign AND get ideas for a multiverse of witches.

But that is not the only thing I wanted from it.

I also wanted to see the differences between various Star Trek-like systems in order to find good NPC for my BlackStar and Star Trek: Mercy games.

Of course, my main source is going to be the challenge founder Carl Stark at Tardis Captain's blog (and of course his Star Trek RPG page).

- FASA Trek

- Frontier Space

- Star Trek Adventures

- Far Trek

- Star Trek RPG (Last Unicorn)

- FASA Doctor Who

- Prime Directive

- Star Trek RPG (Decipher)

- Starships & Spacemen

- Where No Man Has Gone Before

Reading through all of these (and it has been great!) I am more convinced now that my Star Trek Mercy game needs to be a FASA Trek game while BlackStar can be something else; most likely Star Trek Adventures.

Star Trek: Mercy

As I have mentioned previously Star Trek Mercy will take place aboard a Federation Hospital Ship. Its mission is a bit like Doctors Without Borders; they fly into dangerous situations with the goal of helping. While it is a Federation/Starfleet ship I am going to open up character choices to any and all Star Trek races. So humans, Vulcans, Andorians will be expected, but also Romulans, Klingons, Deltans, even Gorn, and Orions if someone can give me a good reason. These crew will not be members of Starfleet, they still belong to their respective worlds, but I also have to, want to, work within canon.

For this, a few guidelines are needed. No Klingon Starfleet officers. Worf was the first and the Federation and the Klingon Empire are at a period of cooled tensions. They are not allies per see, but they are also not shooting at each other. We know from the TNG episode "The Neutral Zone" that Romulans have not had any relations with the Federation since the Tomed Incident of 2311. There is still a Romulan Ambassador on Earth in 2293. That gives me 18 years' worth of gameplay.

I stated in my first post on this that 2295 would be a good year to set this in. Seems like I was on to something. I can even use the Plasma Plague of 2294 as the first mission of the Mercy. We even get a Stardate for it, 38235.3, though that date can't really work for 2294, it doesn't even work well for The Original Series Stardates. That date gives you Wed Feb 24 2360 for TNG and Tue Oct 28 2279 for TOS. Might need to use the FASA Trek Stardate calculations to make this one work!

Also since this is FASA Trek I can borrow some ideas from The Next Generation Officer's Manual. In particular, the notion that there were a bunch of different uniforms in use. Gives me an excuse to use the ones I want. These would be new here and old by the time the USS Protector and the Mystic-class ships roll out.

I am going to need a new ship design too.

What would also be nice is to work in some Original Series Apocrphya into my game; Saavik being half-Vulcan/half-Romulan, Chekov working for Starfleet Intelligence and a touring Chess Master (loosing to the Betazoids), Scotty as a Professor of Engineering at Starfleet Academy before getting lost near a Dyson Sphere in 2294, Sulu as the Captain of the Excelsior and Harriman as Captain of the Enterprise B. Uhura as Demora Sulu's Godmother. I would also like to find out more about Lt. Elise McKennah, played by Michele Specht in Star Trek Continues.

McCoy becoming an admiral, Spock continuing his role as Federation Ambassador, and Kirk disappearing on the Enterprise B. Though those are not really disputed.

I like this idea since it is also the first Trek game my Star Trek loving wife has mentioned she would like to play.

Personal Interlude: The Blizzards of New Jersey

Shooting Straight: ‘Blade Runner’ and Queer Notions of Selfhood

Annie Parnell / February 3, 2021

The irony of the Voight-Kampff test, an analysis that Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) performs to identify “replicant” androids in 1982’s Blade Runner, is that it does not actually prove that his subjects are replicants. Instead, by observing and establishing various responses as “not human,” it proves what they aren’t. By asking suspected replicant Rachael (Sean Young) a series of questions while monitoring her verbal and physical responses with a machine, Deckard is able to quantify precisely how inhuman she appears to be; through noting the absence of what Dr. Tyrell (Joe Turkell) describes as “the so-called blush response” and “fluctuation of the pupil,” the Voight-Kampff test produces a kind of “human-negative” response that isn’t even disproven in Blade Runner’s dystopian Los Angeles when Rachael produces childhood photographs as positive proof of her humanity.

This strategy of collecting data that prove what the self is not connects inversely to Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, a series of short films from the Pop Art movement that depict subjects attempting to stay motionless and hold eye contact with the camera for three minutes, each inevitably failing to not blink or twitch. Jonathan Flatley, for the art journal October, describes these films as revealing “each sitter’s failure to hold onto an identity” of performance, and links the Screen Tests to Warhol’s exploration of queer attraction and selfhood, describing the ways that the intimate series blends desire and identification with another. The Screen Tests form a kind of queer collection of humanities, emphasizing the viewer’s kinship with the series’ subjects through slight, unique movements that contradict the roles ascribed to them, while the Voight-Kampff test forces a sense of self by negation of the other upon the observer. The questions it uses rely on whether or not the subject makes a correctly “human” response, determined by rules of “human” performance that society has projected upon its members. The parallels to queerness are obvious here: in addition to tracking the dilation and contraction of her pupils, one of Deckard’s questions for Rachael asks if she would be sufficiently jealous to discover that her husband finds a picture of a woman in a magazine attractive. Humanity, in Blade Runner, is boiled down to whether or not you conform to a particular, heteronormative pattern of behavior; fail to live up to that pattern, and you are cast out.

In fact, Blade Runner makes repeated references to queerness, both for comedic and dramatic effect. “Is this testing whether I’m a replicant or a lesbian?” Rachael asks Deckard coyly after she’s asked about the woman in the magazine, her eyes inscrutable from behind a cloud of smoke. When renegade replicants Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and Pris (Daryl Hannah) find themselves in the apartment of the sympathetic human Sebastian (William Sanderson), Batty gets down on his knees and positions himself between the other man’s legs. At the scene’s climax, when Sebastian leads them into the Tyrell Corporation, Roy kisses Dr. Tyrell (Joe Turkel) passionately before killing him on the spot. Throughout Blade Runner, the replicants are not only queered and sexualized, but their queerness and any implied proximity to it is as alluring as it is dangerous.

Towards the end of the film, however, both this aversion to queerness and the Voight-Kampff test’s negation-based model of selfhood is challenged when Deckard fights and flees Batty in an abandoned building. Deckard, who has “retired” a collection of replicants over the course of both the film and his career, is suddenly and brutally confronted with one who seems very capable of destroying him. This represents a confrontation between two concepts of humanity and definitions of the self: the isolating, heteronormative notions of the Voight-Kampff test, and a queered, kinship-based model centered on similarity rather than difference. Even ignoring the long-standing fandom debate over whether Deckard himself is a replicant, Blade Runner seems to ask what the functional difference between humans and replicants is, anyway. Just as Warhol argues for an understanding of sexuality and identity based on similarity rather than difference, the fight between Deckard and Batty signifies a brutal process of redefining the self in connection to others, despite coming from a framework that relies on destroying and negating them.

In this final battle, then, Rick Deckard is not only fighting for his life, but fighting to maintain a precarious sense of self that relies on the notion that replicants are fundamentally different from him. Despite this, the gaze of the camera consistently portrays him and Batty as similar to each other, juxtaposing both their bodies and their pain. After a shot that emphasizes Deckard’s fingers, bent at odd angles after Batty breaks them one by one, the camera cuts to a shot of Batty’s own hand curling in on itself as it necrotizes. The parallels are taken to new, gory heights when Batty drives a nail through his atrophying hand in order to trigger a healing response and stop his rigor mortis from spreading. Here, the camera calls back to Deckard having done the exact same thing: his grimaces and the angle of the shot are almost indistinguishable from an earlier shot of Deckard painstakingly and agonizingly popping his fingers back into place.

These instances also emphasize the sadomasochism throughout Deckard and Batty’s climactic chase—a raw, erotic fight to define the self. This is initially teased out through a variety of double entendres in Blade Runner’s script that harken back to the film’s earlier references to queerness. After he breaks Deckard’s fingers, Batty hands him his gun back and tells him that he will stand still by the hole in the wall and offer Deckard one clear shot at him—he must only “shoot straight.” When Deckard fires, Batty jumps out of the way and laughs, shouting gleefully that “straight doesn’t seem to be good enough!” From the other side of the wall, Batty tells Deckard that it’s his turn to be pursued and, his face twitching lasciviously, says that he will give Deckard “a few seconds before I come.” The role that the audience plays in witnessing the physical torment of both men—the pain that they inflict on themselves and each other throughout this chase—is almost pornographic, recasting the viewer as a voyeur absorbed into the crisis of selfhood occurring between them.

The notion of the gaze of an audience upon eroticized pain not only suggests the identification with a subject that the Screen Tests encourage, but also evokes an artistic successor of Warhol’s: Robert Mapplethorpe, whose depictions of gay male S&M are described by Richard Meyer in Qui Parle as insisting on “the photographer’s identity with… the erotic subculture he photographs” and emphasizing the impossibility of “knowing” a person or a culture through outside observation. This suggests potent ramifications for the battle between Deckard and Batty. Much like the Voight-Kampff test proves the absence of humanity through observation rather than identifying its presence, a read of Warhol and Mapplethorpe’s projections onto Deckard’s observation of replicants and the climactic fight with Batty suggests that distinctions of identity are unknowable through opposition and passive perception, and that selfhood relies instead on likeness and identification with others.

When Batty does catch up to Deckard, he maniacally shouts, “You’d better get it up, or I’m gonna have to kill you!” before Deckard attempts to flee out of the window. From this point onward, Deckard is cast in an explicitly submissive light by the camera: as he desperately attempts to scale the decrepit building and escape, we follow him almost exclusively in wide-range shots from above, watching him pant as he stumbles and dangles off the building’s edge. When he reaches the roof, he lies at the top of the building, whimpering. The sexualized power dynamic between Deckard and Batty is only re-emphasized when Batty comes outside and finds him again. Deckard, once more attempting to flee, leaps to the next building over and fumblingly latches onto one protruding metal bar, only to find Batty looming over him moments later after gracefully jumping onto the rooftop. Batty is portrayed, here, as a kind of unhinged replicant dom; the camera showcases him from below in a series of shots that emphasize both his power over Deckard and the physique of his body.

After Batty pulls Deckard up with one hand and throws him onto the rooftop, Deckard continues to struggle below him, breathing heavily as both he and the audience wonder what Batty will do to him. Batty, by this point, has removed most of his clothes; his nakedness, which gave him a primal, animalistic edge during the chase, now makes him seem vulnerable and human as he stands with Deckard in the rain. In a compelling moment of empathy, he physically crouches in order to face Deckard, then muses about the fleeting nature of memory and time before telling Deckard it is “time to die.”

By the end of the scene, when Batty gracefully shuts down, Deckard’s practice of collecting replicants through administering the Voight-Kampff test and violently retiring them has been overhauled through a sadomasochistic struggle that ends in Batty thrusting likeness upon him and ultimately retiring himself. Deckard is left to grapple with a sense of selfhood that is suddenly uncategorizable by opposition. Closing his own eyes moments after Batty has closed his, both he and the audience are left to reckon with Warhol and Mapplethorpe’s queer notions of identity and kinship instead.

![]() Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.

Annie Parnell is a writer and student based in Washington, D.C. who hails from Derry, Maine.

Morelia the Wood Witch for Basic Era D&D (BX/OSE)

I make no excuses for it, I like Ginny Di. She is great and is having more fun with D&D than a roomful of dudes my age. She often has content I enjoy but this week she has given her viewers three more NPCs to adopt or adapt and I just couldn't say no.

So with her (implied) permission here is Morelia the Wood Witch. She has accidentally overdid it on a love potion and now the whole village is madly in love with her. She is very happy to see any new PCs, especially ones not from the village. She will work out a deal with them. If they can bring back enough Pixie's Tongue (it's actually a type of plant) then she can brew up the antidote for everyone. But you better hurry! Two fights for Morelia's hand have already broken out and things promise to get worse soon!

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Ginny Di ???? she/her (@itsginnydi)

Morelia the Wood Witch

8th Level Green Witch*, Elf

8th Level Green Witch*, ElfAbilities

Strength: 12

Intelligence: 15

Wisdom: 13

Dexterity: 17

Constitution: 16

Charisma: 17

Saving Throws

Death or poison: 10

Wands: 12

Paralysis: 11

Breath Weapons: 14

Spells: 13

AC: 9

HP:

Spells

1st Level: Bewitch I, Charm Person, Color Spray

2nd Level: Burning Gaze, Glitterdust, Bonds of Hospitality (Ritual)

3rd Level: Dance of Frogs, What You Have is Mine (Ritual)

4th Level: Bewitch IV, Dryad's Door

*The Green Witch Tradition from my Swords & Wizardry Green Witch book is perfect for her, but I also want this character to have access to some Pagan spells. Plus I want to use her as an NPC for BX/OSE, so she is a Pagan Green Witch. Combine books and mix and match spells.

Helping Morelia now in the adventure will pay off later. Morelia knows about the Tridecium and what is going on with the Witch Queens. She will be an invaluable source of information. That is if she can fix her love potion mishap.

Egbert van Heemskerck (1634 – 1704)

The above four paintings are depictions of the theme of "The Temptation of Saint Anthony."

The above four paintings are depictions of the theme of "The Temptation of Saint Anthony."

An Alchemist Or Apothecary In His Laboratory

An Alchemist Or Apothecary In His Laboratory

The above 10 artworks originate from a series of eight engravings by Toms, published by George Foster c.1730.

Two artworks by the younger Egbert van Heemskerck were previously shared here.

"Attempts to distinguish the work of the elder and younger Heemskerck, where they overlap, have as yet been unsuccessful. An even older Egbert van Heemskerk, often reported to have lived from 1610–1680, may not have existed. Egbert van Heemskerck the Younger was born between 1666 and 1686 and died in 1744, the locations apparently unknown." - quote source

One Man's God: Syncretism and the Gods

Hermes TrismegistusIn the pages of the Deities & Demigods (or Gods, Demigods, and Heroes) the Gods and their Pantheons are fairly clean-cut affairs. Greek over here, Egypt over there, Mesopotamia over there a little more. Norse WAY the hell over there.

Hermes TrismegistusIn the pages of the Deities & Demigods (or Gods, Demigods, and Heroes) the Gods and their Pantheons are fairly clean-cut affairs. Greek over here, Egypt over there, Mesopotamia over there a little more. Norse WAY the hell over there. In real-world mythology and religion, it doesn't work like that. Zeus was, and was not, exactly Jupiter. Ra was Ra, unless he was Amun-Ra or Aten. Dumuzid was Tammuz, except for the times he was his own father. This is not counting the times when religions rise, fall, change and morph over the centuries. Today's God is tomorrow's demon. Ask Astarte or the Tuatha Dé Danann how things fare for them now.

Gods are messy.

It stands to reason that gods in your games should also be as messy.

Now, most games do not have the centuries (game time) and none have the real-time evolution of gods in their games. We use simple "spheres" and give the gods roles that they rarely deviate from. The Forgotten Realms is an exception since its published works cover a couple hundred years of in-universe time, but even then their gods are often pretty stable. That is to make them easier to approach and to make sales of books easier. The Dragonlance books cover more time in the game world, but their gods are another issue entirely.

While I want to get back to my One Man's God in the proper sense I do want to take this side quest to talk about Syncretism.

Syncretism

According to the ole' Wikipedia, "Syncretism /ˈsɪŋkrətɪzəm/ is the combining of different beliefs, while blending practices of various schools of thought." For our purposes today we are going to confine ourselves to just gods.

For game purposes, I am going to use Syncretism as the combination of two or more gods into one. The individual gods and the syncretized god are considered to be different and separate entities.

Now years ago when I proposed the idea that gods can be different than what is stated I go some grief online from people claiming that gods are absolute truth. For example, you can cast a Commune spell and speak to a god and get an answer. But a commune is not a cell phone. It is not email. It is only slightly better than an Ouija board. You have no idea who, or what, is on the other end. If you are a cleric all you have is faith.

So what is a syncretic god like? Some examples from the real world and my own games.

Hermes Trismegistus

Our poster boy for syncretism is good old Hermes Trismegistus or the Thrice Great Hermes. He is a Hellenistic syncretism of the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth. Now, the DDG has these as very separate individuals. Thoth is a Neutral Greater God of Knowledge, Hermes is a Neutral Greater God of Thieves, Liars, and more. From this perspective, there does not seem to be an overlap. But like I say above, gods are messy. This figure is believed to have written the Corpus Hermetica, the collection of knowledge passed down to the various Hermetic Orders that would appear in later antiquity and during the Occult revivals. Even then the Thrice Great Hermes of the Hellenistic period could be argued to be a completely different personage than the Thrice Great Hermes of the Hermetic Orders.

But is Hermes Trismegistus a God? If you met him on the street would that mean you also met Hermes, Thoth, and Mercury? Or can all four walk into a bar together and order a drink? That answer of course is a confounding yes to all the above. Though this is less satisfactory than say having stats for all four in a book.

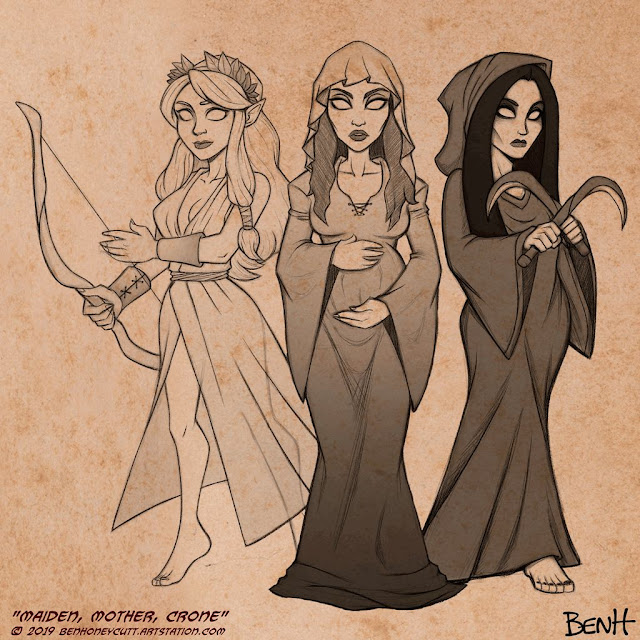

The Triple Moon Goddess Heresy

Back when I was starting up my 4e game and deciding to set it in the Forgotten Realms I wanted to make sure I had a good grasp on the gods and goddesses of the world. I was also already mulling some thoughts that would become One Man's God, so I decided to go full heretic. I combined the moon goddesses all into one Goddess. I also decided that like Krynn, Toril has three moons, but you can't see one of them. I detailed that religion in my post Nothing Like the Sun... and I did something similar to Lolth and Araushnee in The Church of Lolth Ascendant.

Sehanine Moonbow, Selûne, and Shar by Ben Honeycutt

Sehanine Moonbow, Selûne, and Shar by Ben HoneycuttAs expected (and maybe a little wanted) these tended to shuffle the feathers of the orthodoxy. Thanks for that by the way.

This is all fun and everything, but what can I actually *do* with these?

Syncretic Gods make FANTASTIC witch and warlock patrons.

Witches in many pagan traditions in the real world believe that their Goddess is all goddesses. That is syncretism to the Nth degree. I already have a case with Hermes Trismegistus and the Hermetic Order.

Here are some syncretic gods from antiquity and potential roles as patrons.

Apollo-Belenus, Patron of the sun and healing. From the Greco-Roman Apollo and the Gaulish Belenus.

Ashtart, Patroness of love, marriage, and sex. Combines the Goddesses Aphrodite, Astarte, Athirat, Ishtar, Isis, and Venus. Sometimes depicted as the consort to Serapis.

Cybele, or the Magna Mater, Patroness of Motherhood and fertility. She combines many Earth and motherhood-related Goddesses such as Gaia, Rhea, and Demeter.

Serapis, the Patron of Law, Order, rulers, and the afterlife. He is a combination of the Gods Osiris and Apis from Egypt with Hades and Dionysus of the Greek. Besides Hermes Trismegistus, he is one of the most popular syncretic gods and the one that lead archeologists and researchers to the idea of syncretism.

Sulis Minerva, Patroness of the sun and the life-giving power of the earth. She is chaste and virginal where Ashtart is lascivious.

And one I made up to add to this mix and smooth out some edges,

Heka, the Patroness of Magic. She combines Hecate, Cardea, (who might have been the same anyway), Isis, with bits of Ishtar (who has connections to Isis too), and Ereshkigal with some Persephone.

In my own games, I have always wanted to explore the Mystra (Goddess) and Mystara (World) connection.

This also helps me answer an old question. Why would a Lawful Good witch be feared or hated? Simple that Lawful witch is worshiping a god that the orthodoxy deems as a heresy.

A Witch (or Warlock) of the Tripple Moon Goddess in the Realms is going to be hated by both the followers of Selûne and Shar, even if they are the same alignment. Cults are like that.

I am planning on expanding these ideas further.

Another thing I want to explore is when a god is split into two or more gods or demons. In this case I want to have some sort of divinity that was "killed" and from the remnants of that god became Orcus and Dis Pater, or something like that. Orcus, Dis Pater (Dispater), and Hades have a long and odd relationship. This is not counting other gods that have floated in and out of Orcus' orbit like Aita and Soranus.

Character Creation Challenge: Looking Back and Forward

And that is done!

I managed to get through the 31 Day New Year, New Character creation challenge. It was quite a bit of fun. In fact, I might continue this on the 1st of each month. I still have plenty of games to cover.

For the record, here are all the characters created this past month.

- NIGHT SHIFT: Sabrina Spellman

- Dark Places & Demogorgons: Taryn "Nix" Nichols

- Dungeons & Dragons, Original Edition: Deirdre

- Dungeons & Dragons, Basic Edition: Áine nic Elatha

- Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 1st Edition: Rhiannon

- Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, 2nd Edition: Sinéad and Nida

- Dungeons & Dragons, 3rd Edition: Rowan McGowan

- Dungeons & Dragons, 4th Edition: Eireann

- Dungeons & Dragons, 5th Edition: Taryn, Celeste, Cassandra, Jassic, Sasha, and Áedán Aamadu

- Quest of the Ancients: Sarana

- Pathfinder 1st Edition: Labhraín

- Pathfinder 2nd Edition: Oisín

- Castles & Crusades: Fear Dorich

- Spellcraft & Swordplay: Runu and Urnu

- Astonishing Swordsmen & Sorcerers of Hyperborea: Xaltana

- Blue Rose1st Edition, True20: Marissia

- Blue Rose1st Edition, AGE Edition: Seren

- 7th Sea, 2nd Edition: Gwenhwyfar

- DragonQuest 1st Edition: Phygor

- The Dark Eye: Katherina

- Keltia: Siân ferch Modron

- Yggdrasill: Lars son of Nicholas

- Fantasy Wargaming: Marie Capet

- Dark Ages Mage: Lowis Larsdottir

- Chill 3rd Edition: Megan O'Kelly

- C. J. Carella's WitchCraft RPG: Fiona

- WITCH Fated Souls: Alexandria

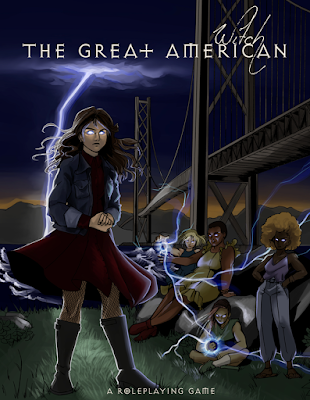

- The Great American Witch: Amy Nakamura

- Mage 20th Anniversary Edition: Brianna

- Mutants & Masterminds: Scáthach the Shadow Witch

- DragonRaid: Solomon

Many of these characters will find some life again in my War of the Witch Queens.

Miskatonic Monday #60: One Less Grave

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

—oOo—

Name: One Less Grave

Name: One Less GravePublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Author: Allan Carey

Setting: Jazz Age Home Counties

Product: Scenario Set-up

What You Get: Twenty-five page, 46.66 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: Romantics Dance to Jerusalem

Plot Hook: The Romantics Society outing to St. Batholomew’s Church on All Hallow’s Eve becomes more than a dance...Plot Support: Plot set-up, three period maps, three handouts, and five pre-generated Investigators.Production Values: Clean and tidy, gorgeous maps, and clearly done pre-generated Investigators.

Pros

# Type40 one-night, one-shot set-up

# Potential convention scenario

# Solid moral climax# Superb maps and handouts

# Pre-generated Investigators nicely fit the setting

# Easily adjustable to other periods# Player driven, not plot driven# Minimal set-up time# Playable in an hour!

Cons

# Horror rather than Mythos scenario

# Pre-generated Investigators are students# Player driven, not plot driven# Playable in an hour!# Investigator interaction hooks and relationships could have enhanced the tension.

Conclusion

# Great production values

# Minimal set-up time# Underwritten Investigator relationships undermine simple, nasty plot.

Character Creation Challenge: DragonRaid

Here we are. The end of the New Character Creation Challenge. First, a tip of the hat to Tardis Captain for getting this going. This has been a lot of fun and I have considered doing it on the first of each month for the rest of the year. Maybe not tomorrow, but who knows.

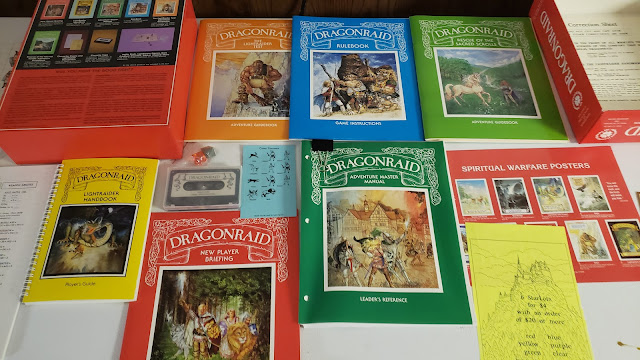

Here we are. The end of the New Character Creation Challenge. First, a tip of the hat to Tardis Captain for getting this going. This has been a lot of fun and I have considered doing it on the first of each month for the rest of the year. Maybe not tomorrow, but who knows. Now for today's last character. Ah. This is a game that has been on my radar for YEARS, decades even. Today feels like the perfect time. So let's make a character LightRaider for DragonRaid!

The Game: DragonRaid

Ok. This game.

So DragonRaid got a lot of grief in the gaming communities I was apart of. I had some Christian gamer friends that thought it was a cheap attempt to capitalize on their faith and some even did not want to mix their D&D and belief. As an Atheist, then and now, I thought it was interesting. As someone who was interested in psychology then and someone with degrees in it now I also thought it was an interesting way to learn something, in this case, Bible verses. I always wanted to see the game for myself.

One thing I have to keep in mind that this "game" is not really an RPG, but a teaching tool in the form of a role-playing game.

The game's author and designer was Dick Wulf, MSW, LCSW, who is, as his degrees indicate, a licensed Social Worker and holds a Masters in Social Work. He had done a lot of work in psychotherapy and ministry. He also played D&D and Traveller. So it seems he actually likes and knows RPGs better than the guys who gave us Fantasy Wargaming!

Plus I have to admit the ads in Dragon Magazine always looked really interesting. I mean seriously, that is an evil-looking dragon and should be stopped and those look like the brave warriors to do it. Even if they need some more armor*. (*that is actually a point in the game! more later)

A while back my oldest son and I saw this game at my FLGS and I told him all about it. He is also an Atheist (as everyone in my family is) and he wanted to get it so we could play the other, evil, side. He wanted to do something with the dragons in the game (he loves dragons) and I of course wanted to bring witches into it (cause that is my raison d'être). Plus this copy still had the cassette tape in it. I mean that is just beyond cool really. So yeah I grabbed it with every intention of having a bit of a laugh with it.

I might be a witch-obsessed Athiest, but I am also an educator and not really an asshole.

The truth of the matter is spending this past week with the game I just can't take a piss on it. The author is just too earnest in his presentation of this game. There is love here, and scholarship, and frankly good pedagogy behind the design. I don't normally mix my professional education background with my game design work. Yes, they can and they do mix. But when I am writing a book on the Pagan witches for Old-School Essentials I am not trying to write a historical treatise on the pagan religions of Western Europe during the time of the Roman Empire. I'll try to keep my facts in line, but I can't serve two masters. I have to write what is best for a game.

DragonRaid also doesn't serve two masters. It serves one and makes that work for both pedagogical reasons (to help young people understand Christianity and their Bible better) and game design reasons (to have a fun roleplaying experience).

For this DragonRaid succeeds in a lot of ways. For this, I simply can't do anything else but admire this game and its design. So no playing dragons here, or me coming up with a witch class to fight the characters. I might do that at home, but I am not going to be a jerk about it.

Besides look at everything you get in this box! I mean seriously, this is some value.

I even got the cassette tape! I don't have anything to play it on though.

Thankfully you can go to the official Lightraider Academy website to get the audio files from the tape.

This company is all in on this game and I have to admit I totally admire them for it.

So expect me to more with this game on these pages including a full review.

The Character: Solomon

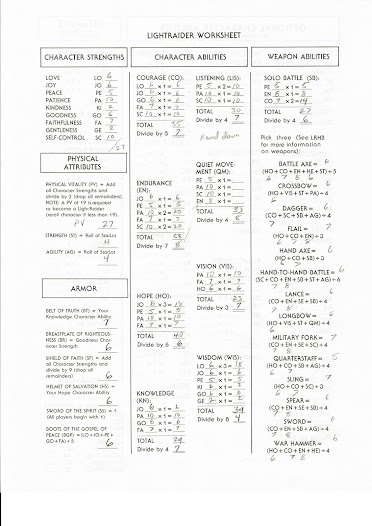

Building your character, the Lightraider, is one of the core elements of this game. It is also why we are here today. There is a pad of Lightraider worksheets and a smaller sized pad of Lightraider character sheets. I am betting I will need both. There is also a blue Game Instructions Rulebook for players.

There are two books that I start with. The red book is the New Player Briefing. The yellow book is the Dragonraider Handbook Player's Guide. I will start with the red since it is the smaller of the two and covers the game basics. The yellow, spiral-bound one covers the in-game background. After some background, we get to the characters on page 60 or so. There are 9 Character Strengths (Love, Joy, Peace, and more, based on Galatians Chapter 5, verses 22-23.) and 2 physical attributes. The first nine are determined randomly on a d10 (called a "Starlot" here. the d8 is a "Shadowstone." I think that is what I am calling d8s from now on!). Many other attributes and scores are determined via derived stats from those strengths. I see why we need/want a worksheet. There are also 8 character abilities that are required and three optional ones.

Note: I am not doing this as a proper review. That will come later. Today I just want to make a LightRaider.

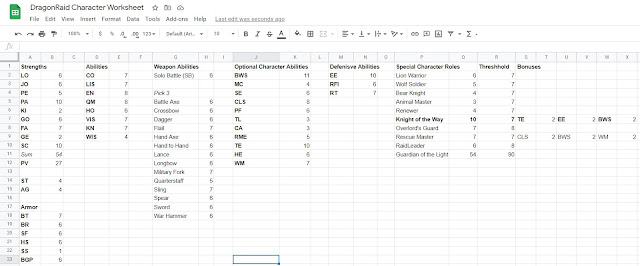

I am going to do this properly and roll all random strengths. Let's see what sort of character I get. Rolling is the easy part, everything else on this sheet requires a lot of math. Not difficult math really, lots of averages, but had I know I would have worked up a spreadsheet.

Ok. I did a spreadsheet anyway. This is the exact thing I would have loved back in the day. I would have written a BASIC program for my Color Computer to help me generate a character. Even now I can see all the code in my head! So let's look over all my numbers and see what character I have here.

Solomon

SolomonKnight of the Way

Character Strengths

Love (LO) 6

Joy (JO) 6

Peace (PE) 5

Patience (PA) 10

Kindness (KI) 2

Goodness (GO) 6

Faithfulness (FA) 7

Gentleness (GE) 2

Self-Control (SC) 10

Character Abilities

Courage (CO) 7

Endurance (EN) 8

Hope (HO) 6

Knowledge (KN) 7

Listening (LIS) 7

Quiet Movement (QM) 8

Vision (VIS) 7

Wisdom (WIS) 4

Blend with Surroundings (BWS) 9 +2 11

Climb Skillfully (CLS) 8

Track Enemy (TE) 8 +2 10

Weapon Abilities

Solo Battle (SB) 6

Sling 7

Flail 7

Crossbow 6

Defensive Abilities

Defensive AbilitiesEvade Enemy (EE) 8 +2 10

Recovery from Injury (RFI) 6

Resist Torture (RT) 7

Armor

Belt of Truth (BT) 7

Breastplate of Righteousness (BR) 6

Shield of Faith (SF) 6

Helmet of Salvation (HS) 6

Sword of the Spirit (SS) 1

Boots of the Gospel of Peace (BGP) 6

Physical Attributes

Physical Vitality (PV) 27

Strength (ST) 4

Agility (AG) 4

You can't see it, but there are a lot of derived stats here. For example, Blend with Surroundings (BWS) is made up of Self-Control doubled (SCx2), plus Patience (PA), plus Endurance doubled (EN). Endurance itself is made up Joy, Peace, Patience (doubled), Faith, and Self-Control doubled, all divided by 7 and rounded down. See why I wanted a spreadsheet.

Can't get much more old-school than this really!

Looking over this character I see he qualifies now for a special Character Role. Normally this would be chosen later after a few games, but let's do it now. Doing the math (again) I see he meets or passes the thresholds for Knight of the Way or Rescue Master. Looking over his stats, mostly at his really poor Kindness and Gentleness scores it looks like Knight of the Way is the better choice. That also gives me a +2 bonus for BWS, TE, and EE.

So. Who is this guy?

Well seeing how low his Wisdom is I thought let's name him Solomon. A reminder of what he needs to work on.

Solomon is a bit of loner. He is not particularly kind nor gentle. He doesn't learn from his mistakes well (low Wisdom) but he is not stupid. What he is however is tireless in his goal of hunting down the enemy of the Overlord of Many Names. He specializes in getting other Lightraiders behind enemy lines and hopefully getting them back out, but that is a job for the Rescue Masters. He knows if he gets caught he can resist the enemy better than most and that is where his true kindness is; if catching him means someone else avoids the Dragon Lord's torturers then so be it.

His combat scores are good, but better with ranged weapons. And yes despite what you may or may not have heard characters ARE expected to fight and kill the forces of evil.

His Faith is pretty good and his Goodness a little less. I think this guy is likely more about wanting to hurt the enemy rather than helping out good people. That will be his struggle.

Well...the real struggle is I don't really know any bible verses so I am not going to get very far with the Word Runes. But I suppose that is the purpose of this game really, to teach them to young adults. This is actually a cool idea; memorizing real bible verses to have an effect in the game. As an educator, I can appreciate this.

I will need to get into that in a future review.

The Links

I am going to be going through this game some more. So I am going to share my collected links here so we both have them for later.

- LightRaiders, the home of DragonRaid, https://lightraiders.com/

- Introduction to DragonRaid, https://vimeo.com/399051861

- The DragonRaid audio files, https://lightraiders.com/dragonraid-tape/

- Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DragonRaid

- Review on RPG.net, https://www.rpg.net/reviews/archive/11/11723.phtml

- Review on Biblical Geek, http://www.biblicalgeek.com/blog/2018/11/22/dragonraid

- Thoul's Paradise has a whole series of posts.

Demand and Dread on the War Road

Zaharets, the Land of Risings, has been free for six generations. Kept as slaves for longer than they can remember, it has been one-hundred-and-fifty years since the Luathi rose up and overthrew the great kingdom of Barak Barad, driving out their masters, the monstrous bestial folk known as the Takan. The rebels anchored their claim to the region by founding cities at the northern and southern ends of the War Road, the route which runs along the coast. From the south came traders—in goods and information, from the Kingdom of Ger, whilst the Melkoni came from the west to establish a colony city-state of their own in the Zaharets. To the east, inland, lies a great desert, home to the horse clans of the Trauj, who trade with the Luathi and guide their merchants across the desert, whilst remaining ever watchful of dangers only they truly understand. In time, Zaharets has become a crossroads where three landmasses and numerous cultures meet. Yet as hard as the Luathi have worked to re-establish human civilisation, the Zaharets is not safe. There are a great many ruins to be explored and cleansed of the Takan, there are secrets of the time before the Luathi’s enslavement to be discovered, bandits prey upon the merchant caravans as they traverse the War Road, and there are dark forces which whisper promises of power and influence into the ears of the ambitious—and there is something worse. Jackals. Jackals give up the safety of community and law and order to go out into the ruins and discover the secrets hidden there, to burn the broken cities free of Takan presence, to face the bandits that raid lawful merchants, and worse… No good community would have truck with the Jackals. For who knows what evil, what chaos they might bring back with them? Yet Jackals face the dangers that the community cannot, Jackals keep the community safe when it cannot, and from amongst the Jackals come some of the mightiest heroes of the Zaharets, and perhaps in time, the community’s greatest leaders when the Jackals decide it is time to retire and let other Jackals face the dangers beyond the walls of the towns and cities of the Land of Risings.

Zaharets, the Land of Risings, has been free for six generations. Kept as slaves for longer than they can remember, it has been one-hundred-and-fifty years since the Luathi rose up and overthrew the great kingdom of Barak Barad, driving out their masters, the monstrous bestial folk known as the Takan. The rebels anchored their claim to the region by founding cities at the northern and southern ends of the War Road, the route which runs along the coast. From the south came traders—in goods and information, from the Kingdom of Ger, whilst the Melkoni came from the west to establish a colony city-state of their own in the Zaharets. To the east, inland, lies a great desert, home to the horse clans of the Trauj, who trade with the Luathi and guide their merchants across the desert, whilst remaining ever watchful of dangers only they truly understand. In time, Zaharets has become a crossroads where three landmasses and numerous cultures meet. Yet as hard as the Luathi have worked to re-establish human civilisation, the Zaharets is not safe. There are a great many ruins to be explored and cleansed of the Takan, there are secrets of the time before the Luathi’s enslavement to be discovered, bandits prey upon the merchant caravans as they traverse the War Road, and there are dark forces which whisper promises of power and influence into the ears of the ambitious—and there is something worse. Jackals. Jackals give up the safety of community and law and order to go out into the ruins and discover the secrets hidden there, to burn the broken cities free of Takan presence, to face the bandits that raid lawful merchants, and worse… No good community would have truck with the Jackals. For who knows what evil, what chaos they might bring back with them? Yet Jackals face the dangers that the community cannot, Jackals keep the community safe when it cannot, and from amongst the Jackals come some of the mightiest heroes of the Zaharets, and perhaps in time, the community’s greatest leaders when the Jackals decide it is time to retire and let other Jackals face the dangers beyond the walls of the towns and cities of the Land of Risings.This is the set-up for Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, a roleplaying game in land akin to the Levant in a post-Bronze Age collapse. Released by Osprey Games, the publisher of roleplaying games such as Paleomythic, Romance of the Perilous Kingdoms, Righteous Blood, Ruthless Blades, and Those Dark Places, this is a roleplaying game inspired by the epic myth cycles of the Ancient Near East—The Iliad, The Odyssey, Gilgamesh, amongst others, as well as the history. They primarily serve as inspiration though, for although there are parallels between the various cultures of Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, so the Ger are akin to the people of Middle/New Kingdom Egypt, the Luathi to those of Israel and Canaan, the Melkoni to Mycenaen Greece, and the Trauj to the dessert and tribal nomads of the Arabian Peninsula, these are cultural touchstones rather than direct adaptations. In Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying, each of the Player Characters will be human, a Jackal from one these four cultures, most obviously a warrior or a ritualist, but also possibly a craftsman, scholar, thief, or even politician, who has eschewed his or her community in favour of secrets, glory, honour, and danger to ultimately protect it.

A Player Character or Jackal in Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is first defined by his Culture, either Luathi, Ger, Melkoni, or Trauj. This defines his virtues—what his culture values are, suggests reasons for becoming a Jackal, faith, magical traditions if a Ritualist, names and appearance, and skill bonuses. A virtue, if relevant, can be used to improve a skill test, essentially a fumble into a failure, a failure into a success, and a success into a critical success. For example, with ‘Fires of Freedom’, a Luathi Jackal can call on the virtue to defend against attempts—physical or spiritual—to take him into bondage or to fight to ensure that others remain free. A Jackal also has five attributes—Strength, Deftness, Vitality, Courage, and Wisdom—which range between nine and eighteen at start. They can be lowered at the cost of Corruption Points and a Ritualist also has a sixth attribute, Devotion, which represents the strength of his devotion to the spiritual world. He has various derived abilities, including Mettle, representing his willingness to fight; Clash Points, representing his battlefield awareness and capacity to react; and Devotion Points, used to invoke rituals, plus Skills which are percentiles and can go above one hundred percent. A Jackal has four traits, two general and two cultural. Each trait is tied to a specific skill and when that skill is rolled, a player can roll an extra die to provide with a choice of ones when determining the percentile value of the roll. This can be advantageous when determining if the player has rolled a critical result—failure of success, either of which requires doubles. So if Jackal had an appropriate trait, his player would roll percentile dice, plus an extra ones die, for example, ‘30’, ‘7’, and ‘3’, he would select the ‘3’ rather than the ‘7’ for a critical success of ‘33’ if the skill is high enough to get a critical success, or opt for the ‘7’ and ‘37’ if not to avoid a critical fumble. For example, ‘Light Touch’ is a general trait which provides this bonus for pickpocketing attempts for the Thievery skill rather than all Thievery related actions, whilst ‘The Jewels of Melkon’ is a Melkoni cultural trait which grants the extra die for Craft rolls related to whitesmithing, or working with gold or silver.

To create a Jackal, a player comes up with a concept, chooses a Culture and an associated virtue, before assigning seventeen points to his attributes (which begin at nine). After deriving various abilities from them, he assigns points to his skills. These are done group by group, so Common, Defensive, Martial, Knowledge, and Urban skills, and the points are different for each group, being derived from various attributes and derived abilities. The player selects four traits, two general and two cultural, selects equipment, and answers some character questions, primarily how and why he is a Jackal. The process is not overly complex, but it does involve a little arithmetic.

Kallistrate is a native of Kroryla, the Melkoni colony established four decades ago in the Zaharets. She is a devotee of Lykos, the founder of the colony and demi-god, and believes it is her destiny to follow in his path rather than that destined by her parents—a good marriage, children, and… boredom. She walked out on a betrothal and following in her family trade, weaving, and sort to make a name for herself in her own right.

Name: Kallistrate

Culture: Melkoni

Cultural Virtue: The Fires of Lust

Strength 12 Deftness 16 Vitality 12 Courage 12 Wisdom 10 Devotion 00

Clash Points: 5 (Max. 5)

Mettle: 12 (Max. 12)

Valour: 18 (Max. 18)

Wounds 6

Valour ×3 (6)

Valour ×2 (6)

Valour ×1 (6)

Common Skills

Craft 66%, Drive 15%, Influence 60%, Perception 55%, Perform 75%, Ride 10%, Sail 10%, Survival 50%

Defensive Skills

Dodge 60%, Endurance 45%, Willpower 45%

Martial Skills

Athletics 50%, Melee Combat 75%, Ranged Combat 30%, Unarmed Combat 40%

Knowledge Skills

Culture (own) 45%, Culture (Other) 25%, Healing 40%, Lore 20%, Ancient Lore 00%

Urban Skills 56

Deception 31%, Stealth 40%, Thievery 10%, Trade 45%

Traits and Talents

Bearer of the Eye of Chium (Perception for Ambushes)

Dangerous Beauty (Influence – Charm/Seduction)

Classically Trained (Rhetoric)

Twin Fangs (Two Leaf-Bladed Swords)

Combat

Damage Bonus: +1d4 Move: 15 Initiative: 16+1d6

Weapons: Twin Leaf-Bladed Swords (1d8)

Armour: Leather (2)

Mechanically, Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying employs the Clash system. This is a percentile system in which rolls of ninety-one and above is always a failure, even though skills can be modified or even raised through advancements above one hundred percent. Rolls of doubles rolls under a skill are a critical success and rolls of double over are a fumble. Opposed rolls are handled by both parties rolling, with the participant who rolls higher and succeeds at the skill check winning. In general, except in situations where there is an extended contest, such as a chase or combat, only one roll is made for a particular skill per scene. Of course, traits and cultural values have a chance of modifying a roll, depending upon the situation, but a Jackal also has several fate Points. These are used to gain a re-roll of a skill check or a damage roll, to add a narrative twist, to invoke a talent that a Jackal does not have, and to prevent a Jackal from dying when reduced to zero Wounds.

If in terms of skills and skill checks, the Clash system in Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is simple and straightforward, combat by comparison, is not. Every combatant typically one main action in a combat round, often a standard type attack, but with the addition of Clash points, combat becomes more dynamic, more heroic. In the main they work as reactions, such as responding to a melee attack and turning it into a clash or dodging a ranged attack, or taking minor actions in addition to a main action. For example, switching a weapon, invoking a rite, or standing up from prone. They can also be spent to improve the effect of an action, such as turning a simple attack into a power attack or sweeping arc, though this costs more in terms of Clash Points. Damage is taken first in terms of Valour Points, and then in Wounds, and once a Jackal begins suffering Wounds, damage can have permanent effects. Suffer enough wounds and a player has to roll for Scarring at the end of a combat.

On the edge of the Luasa Sands, Gashur, a Luathi Hasheer, a seeker of knowledge, has engaged a Trauj guide, Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan, to locate some ruins. Accompanied by her bodyguard, Kallistrate, they have penetrated a cave network and discovered some worked rooms where Gashur has begun to survey some of the mosaics on the walls. Their investigations have alerted a band of Takan, the small, foul and rat-like Norakan led by their leader, one of the hyena-like Oritakan and his lieutenant, the simian Mavakan. The Loremaster states that Kallistrate can use her Bearer of the Eye of Chium Talent to determine if she spots the ambush. Kallistrate has a Perception of 55% and her player rolls percentile dice plus another die for the ones. The percentile roll is ‘99%’! Not only a failure, but a fumble too. Fortunately, the roll of the second ones die results in a ‘5’. Kallistrate’s player choses the ‘5’ and turns the roll into a ‘95%’ rather than the ‘99%’, downgrading it from a fumble to a failure. It means that the three Jackals have been surprised as the Takan come charging into the room, the Mavakan at their head wielding its chipped bronze axe.

Barely able to squeeze through the doorway, the Mavakan runs straight at the nearest interloper, which is Gashur. It attacks first, and the Loremaster rolls ‘18’, opting for a Shield Bash manoeuvre, smashing into the Luathi Hasheer and knocking him flying into the rubble. From behind the Mavakan, the Norakan swarm into the room and over Gashur. If the other two Jackals cannot stop him, they will drag him back into the darkness… On the next round, Kallistrate wins the initiative—she is faster than anyone in the battle, followed by the Norakan and the Oritakan, then Ikeema, and lastly the Mavakan. Kallistrate charges the large beast readying her twin swords to strike. This grants her a total of six Clash Points to spend. Her player rolls ‘40’, enough for Kallistrate to hit with her Melee Combat skill, but her Twin Fangs Talent grants her a second ones die, and this rolls a ‘4’, which turns a success into a critical. However, the Takan have their own supply of Clash points—not as many as the Jackals, but enough—and the Loremaster decides that the Mavakan will spend one to turn Kallistrate’s melee attack into an actual clash. The Loremaster roll’s the Mavakan’s Combat value and it comes up a ‘99%’! Not only a failure, but a fumble, and since the Mavakan fumbled, it suffers maximum damage, ignoring armour, and Kallistrate gains a Fate Point. Since Kallistrate hit, her player decides to power up her attack by making it a Power Attack for two Clash Points. This increases damage by an extra six-sided die, so together with the damage for the weapon and Kallistrate’s damage bonus, the Mavakan suffers a total of eighteen damage. This is more than half of its wounds!

Ikeema uses a Clash Point to ready his bow and fire an arrow at the Oritakan, but misses as the Norakan drag away the helpless Gashur. The Oritakan responds with its ‘Commanding Presence’ special ability, its high-pitched barks driving the Takan band to follow its orders. The Mavakan regains five Wounds too and all of the Takan can adjust their combat rolls as if they had an appropriate trait! Kallistrate’s blow was mighty, but it looks like the battle is not yet going the Jackal’s way…Magic in Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying consists of Rites, its casters known as Ritualists. Each Ritualist enters into a pact with a power or entity of the spiritual realm, following one of the two ritualist traditions of his culture. For example, Luathi Ritualists are either Kahar, the Servants of Alwain, the creator of Kalypsis—greater world—and the initiator of Law, their rites focusing on purity, light, and water, or Hasheers of Ameena Noani, who seek out and gather the knowledge from before and during the kingdom of Barak Barad, their rites focusing on seeing and understanding. In terms of Jackal creation, a Ritualist selects a tradition from one of the two Ritualist traditions for his culture, receives one less general and one less cultural trait, knows the four rituals particular to his tradition, and has the Devotion attribute as well as access to the Magical Skills group.

In play, every Rite has a cost to cast or reserve—essentially to prepare it and cast when needed, a cost in Clash points to cast in combat, and so on. Each Rite is treated as a sperate skill roll, so it is possible to have critical effects and many can be advanced or upgraded. In the long term, this is necessary because Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying only includes four rites per tradition, so there are no extra rites for a Ritualist to learn, although it is possible to study another tradition, and even for non-Ritualists to begin studying a tradition.

Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan is of the Trauj people, a deaweller of the desert who keeps the traditions and magics of his people alive through storytelling. He has explored many ruins in his time and often serves as guide to those foolish enough from along the War Road who want to delve into the secrets that the sands of his homeland hide.

Name: Ikemma of the Ashan Mudi clan

Culture: Trauj

Cultural Virtue: Hearer of Old Tales

Ritualist Tradition: Yahtahmi

Strength 09 Deftness 12 Vitality 11 Courage 12 Wisdom 13 Devotion 15

Clash Points: 4 (Max. 4)

Mettle: 11 (Max. 11)

Valour: 15 (Max. 15)

Wounds 5

Valour ×3 (5)

Valour ×2 (5)

Valour ×1 (5)

Common Skills

Craft 45%, Drive 15%, Influence 20%, Perception 65%, Perform 57%, Ride 55%, Sail 10%, Survival 60%

Defensive Skills

Dodge 40%, Endurance 55%, Willpower 55%

Martial Skills

Athletics 50%, Melee Combat 35%, Ranged Combat 60%, Unarmed Combat 36%

Knowledge Skills

Culture (own) 50%, Culture (Other) 15%, Healing 30%, Lore 60%, Ancient Lore 00%

Urban Skills

Deception 40%, Stealth 45%, Thievery 10%, Trade 44%

Magic

Devotion Points: 15 (Max. 15)

Rites

Zahara Breaks the First Horse 52%

Ilou Slaughters the Eastern Beasts 52%

Yakhia Crosses the Luasa 52%

Tamat Finds the Well of the World 52%

Traits and Talents

Born Under Oura (Willpower)

Ruin Dweller (Lore for Ruins)

Combat

Damage Bonus: – Move: 14 Initiative: 12+1d6

Weapons – Scimitar (1d8), Trauj Bow (1d10)

Armour – Linen (1)

In the fight beneath the ruins, the Takan have spirited Gashur deeper into the darkness and the Mavakan has continued to press its attacks, wounding both Ikemma and Kallistrate. When it unleashes its Howling Fury, it forces a Willpower check on the two Jackals. Both fail, reducing their Valour temporarily. Fortunately, neither fail the second roll, so they are not forced to flee, but discretion being the better part of valour, they decide to retreat with the Mavakan at their heels. They race back through the corridors only to find their way blocked by a chasm—the Takan must have collapsed the bridge over it they used earlier. Kallistrate looks nervously at the distance, wondering if she can make the jump. Ikemma asks, “Tell me, have you heard how we Trauj first came to cross the desert? It was Yakhia who-” Kallistrate looks at the desert dweller incredulously and exclaims, “Is now a good time to be telling stories? We have Takan behind us and a missing employer.” The Yahtahmi laughs and replies that is always time for stories and in telling the story, casts the rite, ‘Yakhia Crosses the Luasa’ which grants them both a bonus to their Athletics skill equal to his Devotion for the rest of the day. With any luck, this will be enough that they can make the jump as they hear the roar of the Mavakan behind them.If Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is a solid design which supports heroic play and the clash of law and order, it is long term play where it begins to shine. In the long term, a player has the chance for his Jackal to push his skills above one hundred percent. This not only opens the option for a highly skilled warrior to divide his martial skills between attacks and dodge attempts and so forth, but further, they open up Advanced Skill Talents. These enable a Jackal to be heroic, even amazing, such as ‘Arrow Snatch’, with which a Jackal can enhance his ability to defend against a ranged attack by grabbing a missile from the air by spending further Clash points. Advanced Skill Talents are provided for each of the five skill groups.

The life of a Jackal is not just dangerous physically, but also mentally and socially. In facing the chaos left over from the remnants of the great kingdom of Barak Barad and the forces of chaos that would tear down the Law of Men, a Jackal can incur Corruption. It can also be incurred for corruptive actions, such as turning to banditry or allying with a chaotic being, and gain enough, a Jackal can have his Fate Points replaced by Dark Fate Points, which can be used to fuel dark rites, and also gain marks of Corruption, such as paranoia and pus-filled blisters. Corruption can also break a Jackal’s connection to the powers that grant him his rites, a major loss for any ritualist. Fortunately, a Jackal can undertake acts of Atonement, which varies from culture to culture, and though challenging, if successful, reduces the Jackal’s Corruption.

Unfortunately, as his Kleos, or renown, grows, a Jackal increasingly comes to the attention of the forces of Chaos. He will also gain recognition and potentially patrons, but the forces of Chaos will reach out to a Jackal, not necessarily to kill him, but tempt or coerce him—and if that fails, well, then kill him. He will have prophetic dreams too, their nature depending upon the Jackal’s degree of Corruption. Of course, no town or society, wants Jackals to return from their ventures with the stain of Corruption, and since Corruption cannot initially be detected, society cannot trust Jackals.

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is played over two seasons—rainy and dry, and at the end of each, a Jackal can undertake a Seasonal Action. One of these can be Atonement, but other options include Carouse, Craft/Commission an Item, Find Rumours, Increase Kleos, and Research. In the long term though, they also include Acquire Patron, Establish Home, and Hospitality, and these last Seasonal Actions represent not those of a Jackal excluded from society, but a Jackal who is attempting transition back into society. This will take years, but if a Jackal survives, he can retire, and the player’s new Jackal can benefit from the wisdom of the retiring one. Not necessarily covered in the roleplaying game, but there is scope here for generational play a la King Arthur Pendragon.

For the Loremaster—as Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying terms the Game Master—there is a Gazetteer of the War Road, focusing upon Ameena Noani and Sentem, the Luathi cities at the northern and southern ends of the War Road, each of the various locations accompanied by a pair of secrets which the Loremaster can expand upon. A bestiary provides a range of threats, including wolves of the four-legged and two-legged (or bandit) kind, the dead, and Takan of various types. There is good advice on running the game too, but this is not a roleplaying game intended necessarily to be run by anyone new to the hobby. Lastly, there are three adventures, designed to start a Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying campaign and lead into Jackals: Fall of the Children of Bronze, the first campaign for the game. The three scenarios will take the Jackals up and down the War Road.

Physically, Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is as well presented as you would expect for a title from Osprey Games. The artwork is excellent and the layout clean and tidy, but it needs a slight edit in places. It is far from poorly written, but it often suffers from a lack of examples in places, or rather a lack of full examples. It certainly could have done with a full example of a Player Character and a longer example of combat to show how the Clash system fully works. Another issue with the roleplaying game is that its tables—especially the combat tables—are not repeated at the rear of the book for easy access.

Conceptually, Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is easy to understand and grasp—the conflict between the Law of Men and Chaos, the tension between society needing those brave enough to face the threat of Chaos, but because they are, never trusted for it. Similarly, its Bronze Age will be familiar and easy to grasp, whether from The Iliad, The Odyssey, or Gilgamesh, or the films of Ray Harryhausen, but as a setting, Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is not as easily accessible. This is a combination of content and presentation, there being a fair number of terms and phrases that the players will need to know to understand the cultures of the setting. Ultimately, the Loremaster will need to work a bit harder with her players for them to match the same degree of buy-in as herself.

Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying is a game which will reward long term play, so it is good to know that it will be followed by Jackals: Fall of the Children of Bronze, but it would be nice to have an anthology of scenarios too. Overall, Jackals – Bronze Age Fantasy Roleplaying nicely balances its tension between the Jackals and society, giving the Jackals a rich environment in which to explore, face ancient threats, be heroic, and ultimately return from to the society they turned away from in order to protect.

Character Creation Challenge: Mutants & Masterminds

Mutants & Masterminds from Green Ronin might feel like a stretch from all the other systems I have done, but really it is quite appropriate given the playstyle I like. And if I am doing a multi-verse of witches here, then it behooves me to throw some supers into the mix.

Mutants & Masterminds from Green Ronin might feel like a stretch from all the other systems I have done, but really it is quite appropriate given the playstyle I like. And if I am doing a multi-verse of witches here, then it behooves me to throw some supers into the mix. The Game: Mutants & Masterminds 3rd Edition

M&M 2nd Ed was one of my favorite superhero RPGs, so it made sense for me to upgrade to the 3rd Edition when it came out. Also given that the same system was being used in the DC Adventures RPG, I just really could not say no.

I have talked a lot about M&M 3 and DC Adventures here. And it is no surprise with my Zatanna postings that I am more of DC fan than a Marvel fan.

I am happy to see the M&M is still going strong. One of the true success stories of the OGL experiment.

Green Ronin even has a Pateron for Mutants and Masterminds at https://www.patreon.com/MutantsAndMasterminds

From the very start of War of the Witch Queens, I knew there was going to be some influences from other games and other universes. Mutants & Masterminds, which already embraces the Multiverse, was an early obvious choice for me. But something that no one knows is that my Come Endless Darkness also had an origin point in M&M. Back then it was going to be Dracula trying to take over the world. I really could not pass up the chance of Dracula fighting someone named Summers. While I moved the whole thing over to D&D (and Dracula to Strahd) I can still see some of the old DNA of M&M in it. Some of the rest moved on to WotWQ. One idea, in particular, was an anti-hero Scáthach.

Now before I get into the character of Scáthach, I do want to address that this is neither the Ulster cycle character Scáthach, nor is the Red Sonja character of Scáthach, The Red Goddess, though in true comic book fashion, both are inspirations. Since she is supposed to be a witch of sorts I am going all the way back to one of my first WitchCraft RPG games that took place at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Plus I wanted a character I could port back over to D&D if I wanted.

The Character: Scáthach the Shadow Witch

Professor Moria Stewart, Ph.D. was a lecturer on classic Irish and Scot Mythology at the University of St. Andrews. She was busy sketching pictures of Dunscaith Castle in Scotland while working on a new paper about Cú Chulainn when she noticed that all her sketches featured the same shadowy figure. She did not remember drawing it, nor even seeing it. She compared it photos she took but nothing was uncovered. She returned to the castle site and was confronted by a Shadow. She fell and hit her head on some rocks below the castle. She was certain to die but the figure came to her saying it would give her power if it could bond to her. Not wanting to die Dr. Stewart agreed and became a creature of shadow herself.

While during the day she goes about her life and teaches her classes to bored undergrads by night (or when she needs too) she can veil herself in shadows and she becomes Scáthach the Shadow Witch!

Neve McIntosh as ScáthachScáthach, The Shadow Witch - PL 10

Neve McIntosh as ScáthachScáthach, The Shadow Witch - PL 10Realm Name: Moria Stewart

Strength 1, Stamina 1, Agility 1, Dexterity 1, Fighting 7, Intellect 3, Awareness 2, Presence 1

Advantages

Contacts, Languages 3, Well-informed

Skills

Athletics 2 (+3), Deception 2 (+3), Expertise: History 8 (+11), Insight 2 (+4), Intimidation 2 (+3), Perception 4 (+6), Ranged Combat: Shadow Blast: Cone Area Damage 10 8 (+9), Stealth 8 (+9), Technology 4 (+7)

Powers

Blend in Shadows: Concealment 2 (Sense - Sight; Blending)

Faerie Fire: Cumulative Affliction 5 (1st degree: Impaired, 2nd degree: Disabled, 3rd degree: Unaware, Resisted by: Will, DC 15; Cumulative, Increased Range 2: perception; Limited: One sense (Sight))

Shadow Blast: Cone Area Damage 10 (shadow, DC 25; Cone Area: 60 feet cone, DC 20, Increased Range: ranged)

Shadow Form (Activation: Standard Action)

Alternate Form (Shadow) (Activation: Standard Action)

Concealment: Concealment 5 (All Visual Senses, Sense - Hearing; Limited 2: Darkness and Shadow)

Insubstantial: Insubstantial 4 (Incorporeal)

Movement: Movement 3 (Safe Fall, Trackless: Choose Sense 1, Water Walking 1: you sink if you are prone)

Flight: Flight 6 (Speed: 120 miles/hour, 1800 feet/round)

Ríastrad: Enhanced Fighting 6 (+6 FGT)

Strength Effect

Shadow Aura: Protection 6 (+6 Toughness; Sustained; Noticeable: Visible effects)

Shadow Magic: Illusion 5 (Affects: Two Sense Types - Sight, Hearling, Area: 30 cft., DC 15)

Shadow Sense: Remote Sensing 5 (Affects: Visual Senses, Range: 900 feet)

Shadow Sight: Senses 3 (shadow, Darkvision, Low-light Vision)

Offense

Initiative +1

Faerie Fire: Cumulative Affliction 5 (DC Will 15)

Grab, +7 (DC Spec 11)

Shadow Blast: Cone Area Damage 10 (DC 25)

Throw, +1 (DC 16)

Unarmed, +7 (DC 16)

Complications

Identity: Shadow Witch is different than Moria

Mythic Weakness: Can't touch any metal while in Shadow form

Languages

English, French, Greek, Latin, Scots Gaelic

Defense

Dodge 3, Parry 7, Fortitude 2, Toughness 7, Will 4

Gender: Female

Age: 35

Height: 5'10"

Weight: 145#

Hair: Black

Eyes: Blue

Power Points

Abilities 22 + Powers 98 + Advantages 5 + Skills 20 (40 ranks) + Defenses 5 = 150

Hero Lab and the Hero Lab logo are Registered Trademarks of LWD Technology, Inc. Free download at https://www.wolflair.comMutants & Masterminds, Third Edition is ©2010-2017 Green Ronin Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.