1995: Everway Visionary Roleplaying

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

In 1995, the hobby gaming industry was deep into the collectible card game craze. Magic: The Gathering has been published in 1993, had become incredibly popular, and made its publisher, Wizards of the Coast, a lot of money. In response, other publishers—large and small—understandably, followed suit, and as they competed in this market, so the hobby gaming industry turned away from the types of games which had supported it over the previous two decades. By 1995, the number of new roleplaying games published that year had diminished to less than half that in previous years. Yet in that year, Wizards of the Coast would publish a roleplaying game which was radically different in concept and format to almost anything which had come before it. A roleplaying game which was so radically different, it would flop. Despite the lack of success though, its simplicity, its focused concept, and its emphasis upon storytelling and drama would all flower in the ‘Indie Roleplaying-Movement’ of the noughties, the concepts of which would go on to be absorbed into the mainstream during the teens. That roleplaying game is Everway Visionary Roleplaying.

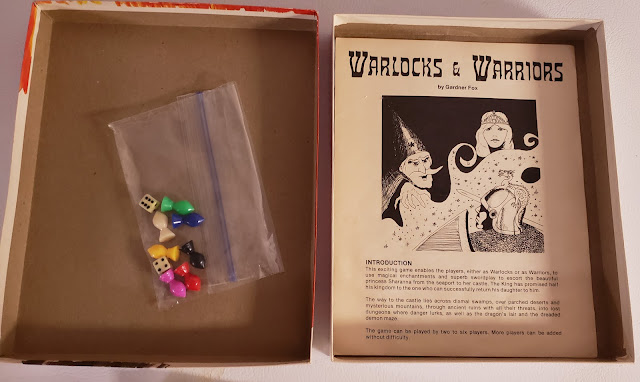

In 1995, the hobby gaming industry was deep into the collectible card game craze. Magic: The Gathering has been published in 1993, had become incredibly popular, and made its publisher, Wizards of the Coast, a lot of money. In response, other publishers—large and small—understandably, followed suit, and as they competed in this market, so the hobby gaming industry turned away from the types of games which had supported it over the previous two decades. By 1995, the number of new roleplaying games published that year had diminished to less than half that in previous years. Yet in that year, Wizards of the Coast would publish a roleplaying game which was radically different in concept and format to almost anything which had come before it. A roleplaying game which was so radically different, it would flop. Despite the lack of success though, its simplicity, its focused concept, and its emphasis upon storytelling and drama would all flower in the ‘Indie Roleplaying-Movement’ of the noughties, the concepts of which would go on to be absorbed into the mainstream during the teens. That roleplaying game is Everway Visionary Roleplaying.Everway Visionary Roleplaying comes in a large box and looks like a traditional roleplaying game, but open up the box and it is clear that it is anything but. In addition to the one-hundred-and-six-two page ‘Playing Guide’, the sixty-four page ‘Gamemastering Guide’ and the fourteen page ‘Guide to the Fortune Deck’, the roleplaying game includes over a hundred, full-colour cards. These consist of the ninety card Vision card Deck, ten Source cards, and thirty-six Fortune card Deck. This is in addition to the two maps, twelve blank Spherewalker sheets, and eleven pre-generated ready-to-play Spherewalker sheets, but what was missing from the box for Everway Visionary Roleplaying is dice. This is because in terms of its mechanics Everway Visionary Roleplaying is diceless. Instead, it uses a combination of the Fortune card Deck and narrative efficacy to determine the outcome of a task or story. Of course, diceless roleplaying games had been seen before, notably Phage Press’ Amber Diceless Roleplaying from 1991, as had card-driven roleplaying games, such as R. Talsorian Games, Inc.’s Castle Falkenstein from 1994. Everway Visionary Roleplaying, though, does not use numbered cards as in the use of a standard playing Deck of cards by Castle Falkenstein, but rather the images upon its cards. Hence Everway Visionary Roleplaying was a visionary roleplaying game in more ways than one.

The setting for Everway Visionary Roleplaying is a multiverse of Spheres—or worlds, each world consisting of numerous different Realms—each connected by a series of Gates. Known Spheres include Ashland, a land of smoking volcanos, nasty cockatrices, and scheming goblins; Canopy, a singular, enormous tree, its inside populated by humans, its roots home to extensive cave systems filled with fantastic creatures; and Pearl of Waves, an undersea kingdom where travel is conducted via bubbles of air or the mouths of giant fish. Typical Realms include the Land of a Million Deities, a conservative Realm of hereditary kings and queens sanctioned by the priests and priestesses of many gods; The Middle Kingdom, a sophisticated Realm dedicated to knowledge and bureaucracy; and the Smith’s Realm, a realm of conquered territories, controlled by regional governors. It is a fantasy setting, one of low magic and high magic, in which demons, angels, godlings, spirits, fairies, dragons, unicorns, and other creatures can be found, but the most common species, in various shapes and forms, to be found throughout the Spheres is mankind, all able to understand the common language known as ‘The Tongue’, a gift from the gods. Perhaps the most famous location in all of the Spheres is that of Everway, a city at the heart of Sphere that has not the two gates typical to most Spheres, but a grand total of three-score-and-ten—if not more!

Every ‘Outsider’ who comes to Everway, experiences the city in a different way. To some it can be well-mannered and bright, to others a city of dark alleys and citizens ready to exploit every visitor or sell them any vice, or ordered and cosmopolitan. It is though, an ancient city, matriarchal, but with a king, and numerous families of note, each of which controls a particular aspect of the city. For example, the Keeper family maintains and guards the Gates, the Scratch family consists of scholars and bureaucrats, and the Wailer family specialises in ceremony of any kind. One type of rare individual drawn to the city of Everway is the ‘Spherewalker’, capable of using the Gates freely and taking the one-week journey to traverse between one Sphere and the next. They can be powerful mages, mighty warriors, enigmatic Shaman, and more, but in becoming Spherewalker, they may be seeking to fulfil a personal quest, to bring justice and an end to evil in any or all Spheres, to search for treasure and personal gain, to atone for crimes committed, or even to gather research and information for the Library of All Worlds in the city of Everway. Each Player Character in Everway Visionary Roleplaying is one of these Spherewalkers.

A Spherewalker is defined first by his Name, typically a common word, or one based on a common word, then a Motive, for example, Mystery, Wanderlust, or Adversity. He also has a Virtue, some way in which he is gifted—it could be a personal trait, a magical gift, or an aspect of fortune. His Fault represents a particular weakness or vulnerability, again a personal trait, magical curse, or aspect of fortune, whilst his Fate is the challenge he currently faces. He is likely to have one or more Powers, limited in scope, but still powerful and distinctive, for example, ‘Fast Healing’, ‘Magical Singing’, ‘Cat Familiar’, ‘Throw Fire’, ‘Invulnerable’, and so on. The ‘Playing Guide’ includes many examples, but a player is encouraged to create his own, a Power typically being a combination of Major, Frequent, and Versatile. This is in addition to the free power which each Player Character Spherewalker possesses. A Spherewalker has four Elements—Air, Earth, Fire, and Water. Air is intellect and communication; Fire, force, athleticism, and combat prowess; Earth, toughness and willpower; and Water, empathy, perception, and wisdom. These are rated between two and nine, each value exponentially greater than the one below it. For each Element, a Spherewalker has a speciality, a skill or ability in which he is better when using that Element. An Element can also suggest a career, such as warrior or acrobat for Fire or poet or physician for Air and Water.

A Spherewalker can also have magic, a mage typically specialising in one of the elements. Thus, Words of Power for Air, Soil and Stone for Earth, Flux for Fire, and Open Chalice for Water. As with Elements, Magic is exponentially more powerful the greater a rating a mage has in it, each rating granting particular advantages. So at a Fluxx rating of three, a Spherewalker can alter minor features, for example, aging milk, freshening the air, rusting metal, and so on, whilst a Soil and Stone rating of six would enable a Mage to save a Realm from a plague or heal a person. How often and for how long a Mage can perform such magics is measured by his Earth Element.

To create a Spherewalker, a player goes through six stages. These start with the player selecting or drawing five cards from the Vision card Deck. In addition to the full-colour illustration on the front, each Vision card has four or five questions on the back about the image on the front. For example, the card depicting two goatherds amidst a field of goats, one of goatherds seeming to steal away with a goat in his arms, has the questions, “How are the two goatherds related?”, “What is the sundial for?”, “How far away is the nearest village? Where is their home?”, and “Why is one goatherd crying?”. The player uses the Vision cards and the questions as inspiration. After deciding upon a Name, Motive, Virtue, Fault, and Fate, the player assigns twenty points between his Spherewalker’s Powers, Elements, and Magic, though all Spherewalkers will have Powers or Magic. The process is in part meant to be collaborative, each player specifically taking the time to introduce his Spherewalker and who he is, whilst the last stage involves the players asking questions about each other’s Spherewalkers, helping each other to understand who their Spherewalkers are. The end result though—and the author’s advice is that everyone should work towards this—should be playable, compatible with the rest of the party, and be prepared to grow and change.

Goat-sent grew up a simple goatherder, alongside her father, tending to the herds belonging to the village in the valley below until she turned thirteen and one goat began talking to her. Not just talking to her, but talking to her things that would happen—and then they did. When the villagers learned of it, they were at first curious, then fearful, and ordered the goat killed. This would happen at the sundial where many of the village’s religious ceremonies took place, but she could not let the goat be killed and ran away with it. Escaping for the first time through a Gate, she sought sanctuary and answers with a Sage, who taught her to focus upon a candle to enter into trances in which she would foretell the future. In time, the rich and powerful of his Realm came to hear their fortune, but not once was she able to tell of the Sage’s future. Yet ultimately, she found the sanctuary constraining and decided to leave, not to go back through the Gate she had used but via the harbour. The ship she embarked upon took her far away, further than the ship had sailed before, from one Realm to the next, where Capybara and her human companion, told her that she was a Spherewalker and that she should follow the sun through to Everway, where perhaps she might find answers. So far, the peoples of Everway have presented with answer upon answer as to the nature of her gift, but none can agree which is correct. So, she seeks answers beyond in the Realms.

Name: Goat-sent

Motive: Mystery

Virtue: Truth (Knowledge)

Fault: Effort Misspent (War)

Fate: Maturity (Winter)

Air: 5 (Singing)

Earth: 4 (Herding)

Fire: 4 (Living under the sun)

Water: 5 (Tracking)

Powers:

Goat companion, 3 (frequent, major, versatile)

Mystic Eye, 3 (frequent, major, versatile)

Goat Tongue, 0

Mechanically, Everway Visionary Roleplaying provides not one, but three means of resolution—the Law of Karma, the Law of Drama, and the Law of Fortune—and the Game Master is free to use whichever one she prefers or feels best fits the situation. With the Law of Karma, a Spherewalker’s Elements, Specialities, Powers, and Magic determine the outcome of an intended action. If the Game Master judges that the appropriate Element, Speciality, Power, or Magic is sufficient, then the Spherewalker will succeed. If not, he will fail. The Law of Karma also comes into play in the long term, potentially rewarding or penalising a Spherewalker depending upon whether an action can be seen as positive or negative. This is of course, up to the Game Master to judge.

The Law of Drama is even simpler. Essentially, the needs of the narrative and the story determines the outcome of an action. Is it appropriate or satisfying at the point in a story that a Spherewalker escape from the cell or does the villain need to turn up to deliver a monologue? Which outcome would make the story better—more interesting, more exciting, more intriguing? The Law of Fortune is slightly more complex, but again relies upon a high degree of improvisation and interpretation upon the part of the Game Master. To determine the outcome of an action, the Game Master draws from the Fortune Deck and interprets the Fortune card as it relates to the situation. Typically, this simply requires the Game Master to draw the one card per situation, whether that is for use of an Element, a Power, or Magic. Going from one law to the next, from the Law of Karma to the Law of Drama to the Law of Fortune involves increasing levels of improvisation upon the part of Game Master and acceptance and participation upon the part of the players and their Spherewalkers to buy into and engage with that improvisation.

Now all of these resolution mechanics also apply to combat as well, whether that is the Law of Karma determining that a Spherewalker is skilled or powerful enough to overcome a foe, the Law of Drama determining that it is appropriate in terms of the narrative for a Spherewalker to win or lose a conflict, or the Law of Fortune relying upon a Fortune card and its interpretation to determine if a Spherewalker wins the conflict or not. This makes combat simple and fast, effectively deemphasising combat as a means of overcoming problems in Everway Visionary Roleplaying. However, combat can be handled in more dramatic fashion, still using the Law of Fortune, but drawing not the once, but from round to round, exchange to exchange. This really works best when a fight or conflict is important, rather than with every single scuffle or brawl.

Mechanically—and thematically, the Fortune Deck lies at the heart of Everway Visionary Roleplaying. Out of the box, it is a deck of thirty-six, full colour, illustrated cards. Every card can be reversed and besides a title, has two simple pieces of text. For example, the text for the Inspiration card is ‘Creativity’, but ‘Lack of Imagination’ when reversed. It is this text which the Game Master is interpreting when applying the Law of Fortune. In the game though, the Fortune Deck is divination tool found in every Realm, but not necessarily as a deck of cards. It could be a great series of bells rung and interpreted in random order each day or the order in which a flock of birds returns to roost at dusk, but it is present in every Realm. The Fortune Deck influences every character—NPC or Spherewalker—and every Realm, so that they each have a Virtue, a Flaw, and a Fate, all drawn from the Fortune Deck. Similarly, each Realm can be created by drawing cards from the Vision Deck and interpreting them just as each player did during the creation of his Spherewalker. The Fortune Deck though, is flawed—by intention out of game, and because in-game, it adds an element of chaos. It was a deity of chaos who stole the thirty-sixth card, leaving a void, and this void, known as the Usurper, is filled with a profoundly negative influence, such as Despair, Sacrifice, or Vengeance, from one Realm to the next. The influence of the Usurper and this negative influence in each Realm will ultimately underlie any Quest that the Spherewalkers undertake there.

Everway Visionary Roleplaying is played as a series of Quests, and again, these can be created using the Vision cards as inspiration and the Fortune Deck to create the conflict in the Quest. Advice for the Game Master covers both the creation of Quests and Realms, and what makes both a good Quest and a good Realm. It also covers running the Quest, bringing the Spherewalkers together, and more. Half of the ‘Gamemastering Guide’ is given over to ‘Journey to Stonedeep’, a lengthy, detailed Quest designed to get a Game Master started with her Everway Visionary Roleplaying game. Several other Quests are outlined in the rest of the ‘Gamemastering Guide’ along with the advice. The much longer ‘Playing Guide’ introduces the setting of Everway in broad detail, enabling the Game Master to develop the particular details as necessary, should she want to involve her Spherewalkers in its daily life, politics, and other events, before guiding both player and Game Master through the stages of Spherewalker creation, and explaining and advising about the rules. The ‘Guide to the Fortune Deck’ explains the Fortune Deck in more detail, its use as a means of divination, and the cards in the Fortune Deck—their correspondences, their meanings, and reversed meanings. If the mechanics to Everway Visionary Roleplaying are simple and easy to learn, in comparison, learning to interpret the meanings of the cards in the Fortune Deck is not. So careful study of the ‘Guide to the Fortune Deck’ is warranted, though as a guide and means of interpretation, rather than being proscriptive. Some advice though could have been included though on how to interpret various situations using the Fortune Deck.

Physically, Everway Visionary Roleplaying is nicely produced and presented. The three books, each 8½ by 7-inches in size, are done in black and white and either pale blue or pale ochre, illustrated throughout with art taken from the Vision Deck, though in black and white rather than colour. The pre-generated Spherewalker sheets are attractively done in full colour, as are all of the cards in the various Decks. The cards in the Vision Deck are done on thick card, and have the feel of collectable trading cards, whilst the cards of the Fortune Deck are more like traditional playing cards—or those of Magic: the Gathering. (That said, it is surprising that the cards of the Vision Deck were not printed on similar card stock.) All of this nicely fits into the plastic insert tray in the box and which has room for further cards—more cards were published for the game.

Yet, for all the high quality of the production values—which for 1995 are excellent, what stands out about Everway Visionary Roleplaying is the quality of the writing. It is engaging throughout, it is helpful throughout, it gives numerous examples throughout, it gives advice throughout, it explains what the game is about and what the job of each player is and what he should do to make the game enjoyable for everyone around the table, and what the job of the Game Master is and what she should do to make the game enjoyable for everyone around the table. Alongside the advice and examples, there is discussion of what happened in the designer’s own campaign, which helps to bring the setting to life and to help the prospective Game Master understand the designer’s intentions. It is all fantastically, superbly useful.

All of this advice is necessary, because with as a trio of mechanics as light as presented in the Law of Karma, the Law of Drama, and the Law of Fortune, those mechanics are open to interpretation—though this is both a feature and the very point of the mechanics, and thus not a negative—and if not necessarily bias, then potential misinterpretation. Everway Visionary Roleplaying is designed to be a game suitable for those new to roleplaying and both its writing style and its advice is helpful in that regard. However, the step from a more tradition, dice and stats, simulationist roleplaying game to a narrative driven, diceless roleplaying game like Everway Visionary Roleplaying will be more of a challenge. Players and Game Master alike, more accustomed to such mainstream roleplaying games will find themselves perplexed by the lack of dice, by the very light, interpretative mechanics, by the emphasis upon the narrative rather than the mechanics, and the questions posed as part of Spherewalker creation will find themselves needing to make some adjustments in how they approach and play the roleplaying game. That though was in 1995. They did gaming differently then, but come forward a quarter of a century, and so many of the ideas and concepts behind Everway Visionary Roleplaying have been taken up by wide aspects of the hobby in the time since its publication, such that if they are not part of the mainstream hobby now, they are an accepted part of gaming.

—oOo—

Rick Swan began his review of Everway Visionary Roleplaying in Dragon Magazine No. 224 (December 1995) by being surprised at the choice of designer for Wizards of the Coast’s new and original roleplaying game and the roleplaying game itself. He described Jonathan Tweet as being talented, but “…not a mainstream kind of guy.” and that whilst he would have expected Wizards of the Coast to want a mainstream product, “In fact, Everway is so far out of the mainstream, it’s barely recognizable as an RPG.” After going into some depth about the roleplaying he states that, “Everway codifies the freeform style favored by me and (I suspect) thousands of other referees. It makes for a brisk game, and Everway, to its credit, plays at blinding speed. But to an unprecedented extent, the success of an Everway adventure depends on the improvisational skills of the referee, his ability to come up with interesting plot twists, characters, and scenic details on the spur of the moment. And players must respond in kind, relying on their imaginations instead of die-rolls to forge their characters’ destinies.” before concluding, “I suspect Tweet has underestimated the average gamer’s aptitude for improvisation. But I could be wrong.”

[As a side note, it curious that Swan concluded with, “I suspect Tweet has underestimated the average gamer’s aptitude for improvisation. But I could be wrong.” (My emphasis.) Given the tone of the review and that Swan thought that Tweet’s earlier Ars Magica would last a year or two, it is quite possible that that what he actually meant was ‘overestimated’. This would better fit the tone and conclusion that the review comes to.]

Ken & Jo Walton made Everway Visionary Roleplaying a Pyramid Pick in Pyramid Number 17 (January/February ’96). After a lengthy review, they concluded, “By now, you’re probably thinking either “That sounds interesting” or “That sounds awful.” This game is not one for simulationists, who want every detail of the physical world accurately portrayed. But for those roleplayers who want to roleplay in a free-form, improvisational way, Everway is a system which actually supports such play, rather than hemming the game round with rules that straitjacket the players’ character conceptions and hamper speed of play with tables and charts.”

Everway Visionary Roleplaying was reviewed by John Wick in Shadis Issue 25 (March 1996), by which time, the roleplaying game had been picked up by Pagan Publishing, the first of several subsequent publishers. He wrote, “Everyway is a game quite unlike anything else I’ve ever seen. The cost is a little high, it may be a bit too off the mainstream for many, and the characters presented arc definitely not Conan clones (white Anglo-Saxon males) which many may interpret as a tip of the hat to “political Correctness”, but all in all, it’s a great game that looks at every aspect of gaming from a different perspective. And that’s what “visionary” roleplaying is all about.” (Note that in 1995, Everway Visionary Roleplaying cost $34.95.)

—oOo—

Everway Visionary Roleplaying is the television series Sliders meets Roger Zelazny’s Amber, played out across a multiverse where patterns in terms of civilisations and the Fortune Deck resonate and repeat again and again. All focused through a lens of the mythic and the mystic, the latter verging on New Ageism, especially with the use of the Tarot card-like Fortune Deck. (This is in addition to the pattern of three which runs throughout the game—the three laws of resolution, the three aspects of divination, and so on.) It seems amazing that this roleplaying game, with its sparse mechanics, emphasis on the narrative, player-focused questions asked during Spherewalker creation, and lack of dice would be released in the nineties at the height of Magic: the Gathering’s popularity. When almost no other roleplaying games were being published and the roleplaying industry looked to be all but upon its death knell. Yet, all these aspects of its design would be explored further in the late nineties with designs like Robin D. Laws’ Hero Wars—which would become HeroQuest and Jenna K. Moran’s Nobilis, before the ‘Indie Roleplaying-Movement’ enthusiastically took them up and ran helter skelter with them. Designer Jonathan Tweet would himself be subsumed by the mainstream by the end of the nineties, becoming the lead designer on Dungeons & Dragons, Third Edition, again for Wizards of the Coast, and then as co-designer, bring some of that radicalism, non-mainstream design into the mainstream with 13th Age for Pelgrane Press.

In 1995, Everway Visionary Roleplaying was ground-breaking. With its advice and extensive examples, it showed how diceless roleplaying could be achieved and played and run with a strong emphasis upon the narrative. Both the means of Spherewalker creation—the use of the Vision Deck and the Fortune deck, along with the questions during the process, and the downplay of combat as a means of resolution, fostered engaging roleplaying and alternative means of solving conflicts and problems. It was incredibly well written, packed with advice, and supported with numerous examples, and yet… In 1995, it was too ground-breaking, it was too radical, and with its Tarot-like Fortune Deck, perhaps overly influenced by New Age religion. Ultimately though, it was not mainstream enough, not commercial enough. In 2021, though…?

Today, Everway Visionary Roleplaying still feels sleek, modern, and elegant. Game design has undergone radical changes since its original publication and now, Everway Visionary Roleplaying fits into the marketplace. It does not feel out of place. If the production values look dated, the design does not. Everway Visionary Roleplaying could be played today and nobody would think it weird or different. As radical as it was in 1995 and as influential as it has been over the last twenty-five years, Everway Visionary Roleplaying is a game from the past that fits today.

—oOo—

A new version of Everway Mythic Roleplaying is currently being funded as part of a Kickstarter campaign. It will be published by The Everway Company.