Outsiders & Others

Gary Con 2022

I had a great Gary Con this past weekend. I spent all my time in the Elf Lair Games / Troll Lords Games booth. I spent my time selling copies of NIGHT SHIFT and Castles & Crusades.

I also got the chance to run into so many people I only get to chat with online. I stopped by the Goblinoid Games / James Mishler Games booth to finally say hello.

I picked up some print versions of books I previously only had in PDF.

They were also selling copies of a new RPG, ShadowDark by Kelsey Dionne of the Arcane Library. It looks rather good.

I also stopped by Bloat Games booth and got the chance to see Eric Bloat and Josh Palmer and grab a copy of their game What Shadows Hide.

Again this looks like a lot of fun.

I am not an autograph hound, but there were some signatures I wanted. Top of the list was Darlene.

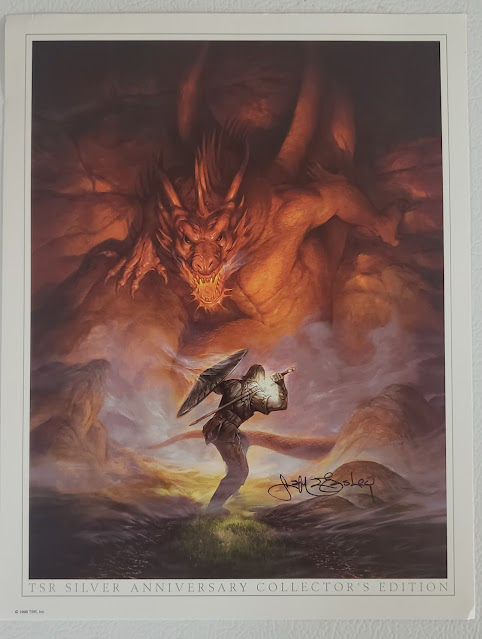

I also got to stop at Jeff Easley's booth and got him to sign his art from the 25th Anniversary Boxed Set.

And of course, I HAD to pick up the tribute/homage covers of the new Castles & Crusades covers.

They do look really nice.

I didn't play any games or run any, but I had a great time.

Looking forward to next year!

Monstrous Mondays: The AD&D 2nd Ed Monstrous Compendiums, Part 7

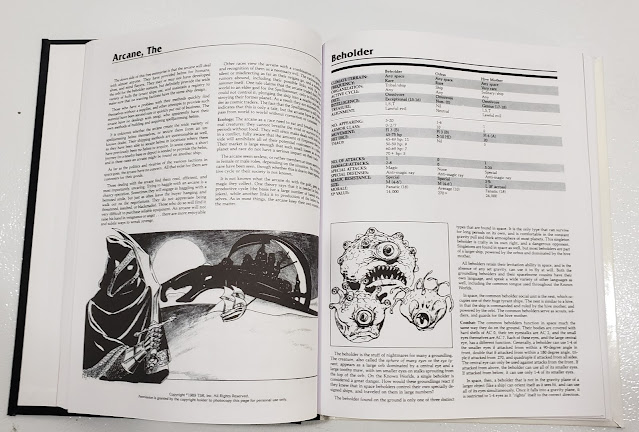

The Monstrous Compendiums would eventually move over to an annual format of perfect-bound soft-cover books. These followed on the footsteps of the combined, hardcover Monstrous Manual, which people liked much better. The idea was to publish a collection of all the published monsters from other products in a Monstrous Compendium style format. But the days of perforated and loose-leaf pages was over and the Annuals and the other books that followed were all bound collections.

The Monstrous Compendiums would eventually move over to an annual format of perfect-bound soft-cover books. These followed on the footsteps of the combined, hardcover Monstrous Manual, which people liked much better. The idea was to publish a collection of all the published monsters from other products in a Monstrous Compendium style format. But the days of perforated and loose-leaf pages was over and the Annuals and the other books that followed were all bound collections.To my knowledge, there were four of these in total. I never owned the print copies, at this time I was getting married and moving into a new house, though I have been able to get the PDFs from DriveThruRPG. Curiously, Annual Vol. 2 has not made it to PDF yet.

Monstrous Compendium Annual - Volume 1

PDF 128 pages, Color cover art, color interior art, $9.99. 129 monsters, Aballin to Xaver.

This first book took on the trade-dress and style of the early AD&D 2nd Ed line and was a companion piece to the hardcover Monstrous Manual.

There are a lot of monsters here I have seen in later editions of the game and some are completely new to me. There are a surprising amount of dragons for example. There are few I recognize from 1st Ed that I guess had not made it over to 2nd ed yet (Gibbering Mouther as one example). There are a also a few I recognize from Ravenloft, given a more "generic" or general approach.

It is a good collection of monsters, to be honest. While the page are formatted to fit a book and not really a Monsterous Compendium (the left or right justification of the text on titles) you can still take this PDF and print your own page to fit into your Monstrous Compendiums. I am going to do this with the dragons for example.

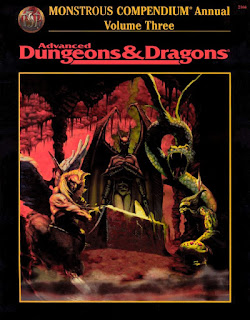

Monstrous Compendium Annual - Volume III

Monstrous Compendium Annual - Volume IIIPDF 130 pages, Color cover art, color interior art, $4.95. 131 monsters, Alaghi to Zhentarim Spirit.

This third annual takes on the trade dress of the later printing AD&D 2nd material when the "2nd Edition" subtitle was removed. The formatting looks transitional. That is I see here the original Monstrous Compendiums eventually morphed into the style I associate with the last years of 2nd ed (and TSR for that matter).

The volume includes a lot of monsters I had seen in various Ravenloft and Forgotten Realms publications at the time and a few that I assume got their origins in the Dark Sun and Planescape product lines. There are some that also first appeared in the Creature Catalog from Dragon Magazine (Lillend for example).

There are few more dragons here too and, in a surprise, two demons / Tanar'ri. So something here for everyone.

This book also includes the Ondonti, the Lawful Good Orcs. So don't try to tell me that "Good" orcs are a new thing.

Monstrous Compendium Annual - Volume 4

PDF 98 pages, Color cover art, color interior art, $4.95. 104 monsters, Ammonite to Zombie, Mud.

This fourth and last Monstrous Compendium Annual was published in 1998 by Wizards of the Coast, though the TSR brand is still on the books. Additionally, this book also indicated where each monster came from whether Forgotten Realms or the pages of Dragon Magazine. There are some that I think are original to this volume. There is even a monster from Alternity here, which is a big surprise!

I would also like to point out that this is the first of these Annuals that acknowledges that it is based on the original D&D rules created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson.

There are quite a few new-to-me monsters here and few I have seen in other places before. It is nice to get them all into one place.

These annuals certainly represent the widest variety in monsters I have sen in any of the other compendiums. If I were to play AD&D 2nd Ed again, I think I would start with these as my sources for new and different sorts of creatures. I am sure that people that were still playing at this time (I had gone on an AD&D sabbatical from 1996/7 to 2000) might be more familiar with these books and these monsters, but it is a joy to open a book, even one 20-25 years old, and see something new.

I am now at the point if I print these out I am going to need a third 3-Ring binder.

Miskatonic Monday #100: Dockside Dogs

The set-up will sound familiar. A gang of besuited, well-dressed criminals arrive at a warehouse having just pulled off an extraordinary crime. Before planning and committing the crime, they had never met before, and even afterwards, they only know each other by their pseudonyms—Mister Black, Mister Red, Mister Green, Mister Purple, Mister Beige, and Mister Silver. The crime has been successfully committed; all they need to do now is follow the boss’ instructions. Lay low in the warehouse until midnight, when he will come for them and ferry them to safety across the bay. It is only a few hours, but not everyone in the gang likes each other and not everyone trusts each other. Perhaps with good reason, because some of them have secrets—and that is before the strange things which seem to be happening in the warehouse. The loot is not what it was when it was stolen—but now it definitely is. Time seems to pass really slowly or really quick. The sound of sirens can be heard right outside the warehouse—but the cops are nowhere to be seen. A baby crying can be heard, but never found in the warehouse. Mister Grey keeps copious notes, but comes and goes. Was he in on the robbery, and if so, should he not be staying in the warehouse like everyone else?If that sounds like the plot of the first film from nineties wunderkind, then you would not be far wrong.

The set-up will sound familiar. A gang of besuited, well-dressed criminals arrive at a warehouse having just pulled off an extraordinary crime. Before planning and committing the crime, they had never met before, and even afterwards, they only know each other by their pseudonyms—Mister Black, Mister Red, Mister Green, Mister Purple, Mister Beige, and Mister Silver. The crime has been successfully committed; all they need to do now is follow the boss’ instructions. Lay low in the warehouse until midnight, when he will come for them and ferry them to safety across the bay. It is only a few hours, but not everyone in the gang likes each other and not everyone trusts each other. Perhaps with good reason, because some of them have secrets—and that is before the strange things which seem to be happening in the warehouse. The loot is not what it was when it was stolen—but now it definitely is. Time seems to pass really slowly or really quick. The sound of sirens can be heard right outside the warehouse—but the cops are nowhere to be seen. A baby crying can be heard, but never found in the warehouse. Mister Grey keeps copious notes, but comes and goes. Was he in on the robbery, and if so, should he not be staying in the warehouse like everyone else?If that sounds like the plot of the first film from nineties wunderkind, then you would not be far wrong.This is the set-up for Dockside Dogs, a scenario for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition from its co-designer, Paul Fricker. It is a gangster themed, single-session, one-shot scenario which more or less follows the plot of almost any ‘Heist Gone Wrong’ film, from Rififi to Reservoir Dogs—though more the latter than the former. It is set in the nineties, but could just as easily be set in other time periods, and whilst it has obvious American trappings it could be easily adjusted to almost any other big coastal city. As a one-shot, it is designed to be roleplayed by six players and to that end comes with over twelve Investigator sheets so that each of the six gangster Investigators can be played as male or female. There are guidelines for running the scenario with fewer players, but Dockside Dogs is at its best with the full cast of six players and thus six gangsters. Each Investigator sheet includes a personal description, backstory, treasured possessions, and traits for that gangster, as well as a list of what each gangster thinks—and in some cases knows—of his or her fellow crew members.

Dockside Dogs begins with the gangsters arriving at the warehouse in two groups. Exactly what happened earlier in the day will be established through flashbacks and here Dockside Dogs begins to diverge away from what the traditional Call of Cthulhu investigation. The investigation, such as it is, is not through newspaper morgues or in libraries, but into each other. This is spurred on by events which the Keeper slips into the scenario exacerbate the sense of paranoia and uncertainty which pervades the scenario. Another difference between Dockside Dogs and other scenarios for Call of Cthulhu is that it encourages creativity and improvisation upon the part of the players and the Keeper. The effect of these scenes is twofold. First, they strengthen the links between the gangsters, and second, they call back to the film which inspires the scenario and enforces the genre.

Physically, Dockside Dogs is well presented, clearly written, and consequently easy to run with relatively little preparation. The Investigator sheets have all been customised for the scenario and are nicely individualised from one character to the next. Interestingly, there is some foreshadowing on some of the Investigator sheets, which effectively calls for the players of those Investigators to go along with the plot, again to enforce the genre and call back to the scenario’s inspiration.

Just as the genre and film inspiring Dockside Dogs is obvious, so is the Mythos inspiring it. However, just as the scenario asks the players to lean into its genre and filmic inspiration, it is also asking them to lean into the Mythos inspiration as well, though that inspiration is used in a markedly different fashion. With its combination of genre and single-session, one-shot format, Dockside Dogs is reminiscent of the Blood Brothers and Blood Brothers 2 anthologies, but is a more modern, storytelling-influenced version of that format. Dockside Dogs involves ‘blood brothers’ of a different kind in what is a tense and potentially bloody character study.

Cartoon Corpse Cracking Action!

The rise of the dead and the zombie outbreak has been visited again and again in board games and roleplaying games that the concept has become a cliché and the question has to be asked with each new game, “What makes this zombie game different?” such that a playing group will pick it up and play it. So the question is, “What makes Zombicide Chronicles different?” As the name suggests it is based on the boardgame of the same name, Zombicide, in which the players control the fate of the ‘Survivors’ as the zombies rise up, infect their town, and they fight back, becoming ‘Hunters’, taking the violence to the corpse cortège… This is no Deadof Winter or The Walking Dead where every day is a desperate battle for survival—and that is even before the survivors encounter any zombies! Instead, Zombicide is a game in which the players ‘team up, gear up, level up, take ’em down’ and batter, slash, hack, and shoot the members of the cadaver cavalcade and it is this sensibility which is brought to Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game.

The rise of the dead and the zombie outbreak has been visited again and again in board games and roleplaying games that the concept has become a cliché and the question has to be asked with each new game, “What makes this zombie game different?” such that a playing group will pick it up and play it. So the question is, “What makes Zombicide Chronicles different?” As the name suggests it is based on the boardgame of the same name, Zombicide, in which the players control the fate of the ‘Survivors’ as the zombies rise up, infect their town, and they fight back, becoming ‘Hunters’, taking the violence to the corpse cortège… This is no Deadof Winter or The Walking Dead where every day is a desperate battle for survival—and that is even before the survivors encounter any zombies! Instead, Zombicide is a game in which the players ‘team up, gear up, level up, take ’em down’ and batter, slash, hack, and shoot the members of the cadaver cavalcade and it is this sensibility which is brought to Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game.Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is published by CoolMiniOrNot and Guillotine Games as part of the successful Kickstarter campaign for Zombicide: 2nd Edition. It is designed as both a standalone roleplaying game set in the Zombicide universe and a roleplaying game which is compatible with Zombicide, 2nd Edition, so that the cards and the dice and more can be used with the roleplaying game. This compatibility does lead to some oddities with regard to terminology if the players have experience with other roleplaying games. If they are coming to the roleplaying game after playing the board game, then this is not an issue. If however, they have not, then a little adjustment might be required.

A Survivor in Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is defined by his Skills, Attributes, and Proficiencies, and through the combination of Attributes and Proficiencies, his Actions. Skills are actually special abilities, which work under particular situations, for example, ‘Born Leader’ enables a player to give another player an extra Support Action in combat or ‘Beak-in’, which enables a player to get past standard locked doors or windows without any noise or specialist equipment. There are three Attributes—Muscle, Brains, and Grit, and Proficiencies—Athletics, Attitude, Background, Combat, Perception, and Survival—are categories in which a Survivor can specialise. Attributes and Proficiencies are rated between one and three and laid out on a grid with Attributes along the top and the Proficiencies listed down the side. In play, the Proficiencies are cross-referenced with the Attributes to give an Action, for example, cross-reference the Background Proficiency with the Brains Attribute to get the Education Action or the Perception Proficiency with the Grit Attribute for the Scout Action. It is Actions that might be seen as skills in other roleplaying games.

To create a Survivor, a player first selects an Archetype. There are twelve of these, each with a favoured Proficiency, Attribute, and four starting Skills. They include a BMXRider, a Hacker and Boxer, Bus Driver, Resourceful Foreman, Postwomen, and more…There is, of course, a boxed set of miniatures for the twelve archetypes, which would enable the player-created Survivors to be used in conjunction with the board game. All come with a name, a quote, and a suggestion as to why a player might pick that archetype. The player selects four starting Skills and four favoured Actions (these are underlined on the sheet), and assigns ratings of one, two, and three to his Survivor’s Attributes. He sets two Proficiencies at three, three at two, and one at one. The Survivor also has some gear—a readied weapon, a holstered weapon, and the contents of a backpack.

Alternatively, a player can instead create a Survivor from scratch, ignoring the Archetype step, though they are fun. This would free a player to choose all four of his Survivor’s favoured Proficiency, Attribute, and four starting Skills. A set of tables provides options for the Survivor’s Prologue—when he first heard of the outbreak, firsts aw a zombie, his first Zombicide, and more. The process is quick and easy, and defines the Survivor in broad strokes.

Stanley Redfield

Occupation: Reformed Burglar

Level 0

Habit: Rolls a cigarette, but never lights it. Had to give up for health reasons.

Looks: Unshaven, shifty, and balding

Hit Points: 4

Stress: 6

SKILLS

Break-in, Is That All You Got?, Precision, Mindfulness

ACTIONS – Muscle 3 Brains 2 Grit 1

Athletics 2 Stunt Sneak Endure

Attitude 1 Appeal Convince Hearten

Background 2 Security Education Contacts

Combat 2 Fight Shoot Cool

Perception 3 Spot Evaluate Scout

Survival 3 Scavenge Tinker Heal

GEAR

Pistol, crowbar

When did I first hear about the outbreak?

My brother-in-law died and I heard he came back from the dead…

When did I first experience the outbreak?

My neighbour’s dog wouldn’t shut up, and when I went to investigate, the crotchety old witch nearly ripped my damned arm off…

When was my first Zombicide?

I helped clean up the neighbourhood. Not like the cops were coming…

What happened to your significant others?

I ain’t heard from my son. I sure hope I can find him and he is okay.

What did I take with me?

My cell phone. Need to find a charger for it though…

What did I leave behind?

My favourite book, Angels & Demons

How did I meet the other survivors?

Yeah, one or two were friends.

Mechanically, Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is simple. A player cross-references a Proficiency with an Attribute to give an Action, the combination of values for the Proficiency and the Attribute give the number of dice to be rolled for the Action. This generates a base dice pool which ranges in size from two to six dice, but to this can be added bonus dice for a Favoured Action, equipment, and the difficulty of the situation, which can increase or reduce the number of dice to be rolled. This can increase the number of dice up to a total of twelve, and any dice after the first six, are rolled as Master dice. Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game has its own dice. These are six-sided dice, marked with a Zombie Head on the one face and a Molotov Cocktail on the six face, but ordinary six-sided dice can be used instead just as easily. The basic dice should be all one colour, whilst the Master dice another. When rolled, results of the Molotov Cocktail count as Successes. Only one success is required for an Action to succeed, but multiple Successes rolled improve the outcome. If a Zombie Head is rolled on a Mastery Dice, then the player can reroll it once. If there are more Zombie Heads than Molotov Cocktails (or ones versus sixes), then Trouble can ensue, such as a weapon being dropped or friendly fire in combat!

For example, Stanley Redfield is out scouting downtown and discovers a pharmacist which has only been partially looted. There are zombies moving around and he wants to break in without alerting them. His player selects the Security Action, which effectively means he is cross-referencing his Muscle of three with his Background Proficiency of two. This gives him a base dice pool of five dice, but since Security is a favoured Action, this adds one Bonus Die. The use of his crowbar also adds another Bonus Die. Which means altogether, Stanley’s player is rolling six dice and one Mastery die.Combat uses the same mechanics, with only one success needed to hit and weapons inflicting a fixed amount of damage. Combat consists of ‘Opening Shots’ of ranged combat, followed by proper Combat Rounds of melee combat. Zombies are attacked in speed order, from the slowest to the fastest, unless the Survivor takes the Aim move. Damage needs to be enough to kill a zombie in one go, or not at all, and some of the zombies, like the Abomination, can withstand more damage than most weapons can inflict. In this instance, the Survivors need to master their weapons with the right Skills. Zombies attack and automatically do damage in the Combat Rounds with the Game Master not needing to roll. Armour provides protection, but can be damaged. Another option is that the Survivors can take the Evade move.

One advantage a Survivor has in combat is that he can inflict Stress on himself in return for turning a failed roll into a Success. Whether this is possible depends on the weapon and its Accuracy value, and the number rolled on the dice. For example, the fire axe has an accuracy of four plus. If the player rolls just numbers on the dice rather than Zombie Heads or Molotov Cocktails, he can check the numbers, and if any of them are four or five, he can take a point of Stress to turn it into a Success. Stress though is a finite resource and there is a limit to how often a player can use it. Once his limit is reached, a Survivor will need to find a way of relieving his Stress.

All weapons have an Accuracy value like this. The ranged weapons in Zombicide Chronicles are the generic pistol, shotgun, and so on, but the melee weapons are more individual—baseball bat, chainsaw, katana, kukri, and more. They all have their own cards in the board game which can be incorporated into Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game.

As play progresses and a Survivor rolls Successes, he accrues Adrenalin. This is tracked and as it rises, he can use more and more of his Skills (or special abilities). Adrenalin is also gained for achieving objectives. The Skills are rated either Basic, Advanced, Master, and Ultimate. At the beginning of a Mission, a Survivor can use just his Basic Skills, meaning that he gets better and better as the Mission proceeds.

Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is played in two phases—the Shelter Phase and the Mission Phase. The Shelter Phase is when the Survivors plan and prepare the situation in their current shelter and nearby, including checking for supplies (if they have insufficient supplies, the Survivors will suffer Conditions in the Mission Phase), gathering rumours, making things, studying or training, and creating and defending a shelter. The Mission Phase is when the Survivors go out and perform the mission itself. Various types of missions are discussed, including going on a supply run, exploring, making a rescue run, and more. This is combined with the ‘World of Zombicide’, which describes the various districts and locations of an archetypal city and takes up the last third of the Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game. Although there is no actual scenario in the roleplaying game, the ‘World of Zombicide’ has plenty of ideas and NPCs for the Game Master to use.

In terms of zombies, Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game has its own ‘Zombipedia’. There are four base types of zombie—Walker, Fattie, Runner, and Abomination, and these are typically organised in play into hordes which the Survivors will need to take down. The Game Master can customise these though to add variation, and several mutated and animal zombie types are also included. There is good advice for the Game Master on running the game, including suggestions on how to set the right tone for her players, though this is a horror game after all.

Physically, Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is big, bold, and in your face. It is heavily illustrated with lots and lots of cartoon style artwork, decent maps and floorplans, and fully painted panoramas of the city. The book is well written and easy to read.

There are any number of zombie-themed roleplaying games, but with its simple mechanics and cartoon zombie action, Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game is easy to pick up and easy to play. The compatibility between Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game and the Zombicide: 2nd Edition board game means that there is plenty of potential for cross play between the two. So, the various equipment cards and map tiles from Zombicide: 2nd Edition could be used with Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game to play out the action of the Mission Phase, but equally, the Survivors created using the Zombicide Chronicles: The Roleplaying Game could be used to play through the content in Zombicide: 2nd Edition. However, given that potential for cross compatibility, there is no advice on how to do that, which is an odd admission since the roleplaying game was funded as part of the Kickstarter for the board game.

Zombicide Chronicles: TheRoleplaying Game is a grim—but not dark—post apocalyptic roleplaying game with genre elements and a setting of the ‘World of Zombicide’ that will be familiar to most gamers. This does not stop it from delivering fast-paced, big, zombie-fueled tension and action.

The Other OSR—Kuf

The world is not what it seems. There is a barrier which surrounds reality and gives it the order and natural laws that mankind, blind to the truth that only outsiders, cultists, and the oddballs recognise and follow, for beyond the barrier lies chaos… At first a reflection of our reality, but then a distorted version, and further and further away until there are no natural laws and nothing that can be recognised of our reality. The barrier is not immutable, for in places it is weak and there are things and beings on the other side which want to get through to our reality, and even worse, men and women who would help them, and even welcome them through. Some work alone, but others form cults, hiding behind other organisations and planning and plotting away in secret, hunting for and researching the knowledge that will bring their plans to fruition, whether that is for power, to discover their truth about the cosmos, or simply to destroy reality. There are others on the same path, who through personal trauma have come to realise the true nature of reality, but do not plot, plan, or research ways in which to pierce the barrier for their own ends, but to prevent monsters from succeeding or being let in… They are outsiders, weirdos, and oddballs, pulled into a maelstrom of terrible events which nobody will ever believe, but returning scarred and traumatised, knowing that they may need to do it again and again, because no one else will.

The world is not what it seems. There is a barrier which surrounds reality and gives it the order and natural laws that mankind, blind to the truth that only outsiders, cultists, and the oddballs recognise and follow, for beyond the barrier lies chaos… At first a reflection of our reality, but then a distorted version, and further and further away until there are no natural laws and nothing that can be recognised of our reality. The barrier is not immutable, for in places it is weak and there are things and beings on the other side which want to get through to our reality, and even worse, men and women who would help them, and even welcome them through. Some work alone, but others form cults, hiding behind other organisations and planning and plotting away in secret, hunting for and researching the knowledge that will bring their plans to fruition, whether that is for power, to discover their truth about the cosmos, or simply to destroy reality. There are others on the same path, who through personal trauma have come to realise the true nature of reality, but do not plot, plan, or research ways in which to pierce the barrier for their own ends, but to prevent monsters from succeeding or being let in… They are outsiders, weirdos, and oddballs, pulled into a maelstrom of terrible events which nobody will ever believe, but returning scarred and traumatised, knowing that they may need to do it again and again, because no one else will.This is the setting for Kuf—meaning oddball or eccentric—a modern-day roleplaying game of Gnostic horror published by Wilhem’s Games. As written, it is set in modern-day Sweden, but can be easily set elsewhere and it uses the light mechanics of Knave. The result is a collision of esoteric horror and the Old School Renaissance, the Player Characters simply drawn and decidedly fragile, both mentally and physically, in the face of the resources that the cults can bring to bear and the things that they might summon. It is played in three distinct phases—Exploration, Confrontation, and Recovery. In the Exploration Phase, the Player Characters investigate, conduct research and interviews, monitor suspects, purchase and ready equipment, and ultimately, prepare for the Confrontation Phase. The Confrontation Phase is when the Player Characters sneak into the cult headquarters or summoning site, pierce the barrier and confront the things on the other side, and hopefully disrupt the ritual or plans of the cultists. The Recovery Phase is more formal and takes a month, but can take place between investigations or sessions. This is when the Player Characters plan the next investigation, seek medical care, study an artefact or read an esoteric tome, buy illegal equipment, recruit companions to the cause, and so on. Mechanically, all of these activities are rolled for, so might work, or even might be cut short because the next Exploration Phases begins—perhaps because the cultists they stopped in the previous Confrontation Phase have come looking for them!

A Player Character in Kuf looks like a Player Character in Dungeons & Dragons. He has the six requisite Attributes—Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma. Five of these cover aspects as you would expect. Thus, Strength is used for melee attacks and physical Saving Throws; Dexterity covers agility and speed; Constitution to resist poison and sickness; Intelligence for handling concentration, recall, using magic and more; and Charisma for interacting with NPCs and recruiting companions. The difference is that Wisdom, in addition to covering the usual perception and intuition, actually handles ranged attacks! It is a radical change, but it means that Wisdom can be used as a more active attribute and that ranged attacks are associated with perception, and also it shifts some of the traditional emphasis in other retroclones away from Dexterity.

Each Attribute has both a bonus and a defence. The bonus is equal to the lowest value rolled during character creation. This is done using three six-sided dice, in order, as is traditional. Thus if a player rolled three, four, and five, to get a total of twelve, the bonus would be three. The Defence for an Attribute is the bonus value, plus ten. A Player Character also has a Level, which begins at zero, and represents the degree to which he has been affected by exposure to the true nature of the universe. As gains Levels, he will be changed by the universe, and gain odd powers or gifts, such as halo of light forming around his head which he must constantly concentrate on has to continuously concentrate to suppress, becoming semi-fireproof, or gaining true sight and so be able to see through the disguises of the creatures and things that have managed to cross through the barrier. Both Hit Points and Mind Points—the latter the equivalent of Sanity found in other roleplaying games—are derived from combinations of the attribute bonuses. A Player Character begins play with no armour and thus the base Armour Defence value, though he may be able to purchase armour during play and thus improve it. He will also have a Background or occupation, and a trauma or event which exposed him to the maelstrom. This trauma also grants him starting Experience Points.

To create a character in Kuf, a player rolls three six-sided dice for the six Attributes, noting their Bonus and Defence values, and then rolls for Background and Trauma, plus the starting Experience Points from the Trauma. He can also roll or pick any extra languages the character knows and either pick or roll for a name.

Emma HanssonBackground: FarmerTrauma: Insanity (Batrachophobia)Languages: Swedish, Hebrew, French, Arabic, Spanish, German

Level 0Experience Points: 139

Hit Points: 8Mind Points: 09

Armour: None Bonus +1/Defence 11

Strength 16 Bonus +5/Defence 15

Dexterity 07 Bonus +1/Defence 11

Constitution 08 Bonus +2/Defence 12

Intelligence 15 Bonus +5/Defence 15

Wisdom 14 Bonus +2/Defence 12

Charisma 11 Bonus +3/Defence 12

Mechanically, Kuf uses a throw of a twenty-sided die against a standard difficulty. If the player rolls sixteen or more, his character succeeds at the action. When it comes to opposed Saving Throws, this can be rolled by the player or the Game Master. For example, if a Player Character attempts to grapple a thief who just robbed him, his player could roll and add his character’s Strength Bonus against the thief’s Dexterity Defence, or the Game Master could roll against the Player Character’s Dexterity Defence adding the thief’s Dexterity Bonus. The option here is whether or not the Game Master and her players want to play Kuf with player-facing rolls or use the standard method in which both players and the Game Master roll as necessary.

The option is also included to use Advantage and Disadvantage, as per Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. Typically, this will come from the situation or the environment, but it could also come from any one of the several Traits rolled or chosen during character creation. The mix of these underlie who or what a character is and so bringing them into play encourages roleplaying.

Combat in Kuf is kept simple. The Player Characters and their opponents both have a fifty percent chance of winning the Initiative, and attack rolls, whether using the Strength Bonus for melee attacks or the Wisdom Bonus for ranged attacks, have to be greater than the Defence value of the armour worn. Alternatively, if using player-facing rolls, the defending player would roll his character’s Armour Bonus to beat the attacker’s Defence value. In addition, Opposed Saving Throws can be used to do Stunts, such as stunning an opponent, knocking them over, disarming them, smashing armour, and so on. Stunts do not do damage though, although they can be combined with an attack attempt if the attacker has Advantage. This is instead rolling the two twenty-sided dice which is normal for Advantage.

Successful attacks do not just inflict damage per the weapon’s die size, but also by the type of attack. Blunt force trauma inflicts light wounds; shots, stabs, and cuts inflict serious wounds; destructive damage inflicts critical wounds; and beyond that, there are permanent wounds. On the character sheet, there are boxes for tracking Hit Points and wounds, each type of wound being marked with a different symbol. One type of wound can upgrade a lesser type, and once all of the boxes have been filled in on a Player Character’s wound track, his player starts again at the beginning, but fills them the boxes in with the worse wound type. For example, if a Player Character has all of his wound boxes filled with light wounds by being beaten up by thugs armed with baseball bats, and the beating continues, his player would start filling up the wound track with serious wounds. In combat critical hits either add another die’s worth of damage or upgrade the wound type.

Kuf then does the same for the Mind and Mind Points with sources of stress, which can be seeing beyond the barrier for the first time, encountering a frightening monster, suffering from a phobia, being the victim of crime, and so on. Like physical wounds, the effects of stress can be light, serious, critical, or permanent, and greater effects can overwrite the lesser effects. However, when a greater stress type overwrites a lesser type, a Player Character can suffer a Stress Reaction. This might be that he freezes on the spot, fleeing, or even attacking the source of stress. Critical trauma suffered through stress can also inflict nightmares, phobias, and worse.

In both cases of physical and mental damage, permanent wounds reduce a Player Character’s attribute bonuses each time permanent wounds are suffered. Player Characters in Kuf are meant to be fragile, but this gives them a greater degree of resilience than is found in Knave. However, there is a brutal nature to that resilience as more wounds are suffered and the damage gets worse and worse—and Kuf applies this to both mental and physical damage.

For the Referee there is advice on running the game and its three phases—the Exploration Phase, Confrontation Phase, and Recovery Phase—as well discussions on the nature of the barrier and what lies beyond it, ritual magic, cults and cultists, artefacts and books, and creatures from nightmare, and in general the advice is good. However, there are problems with it, one lesser, three greater. The lesser problem is that the section for the Referee is not as well presented and in a lot of the table results for various tasks, like seeking medical care or purchasing illegal equipment, there are sections missing. The first of the greater problems is that the Kuf does not give the Referee enough threats or rituals or books or artefacts for her to really get started or take inspiration from. There really is only one of each and it is just not enough.

The second greater problem is that there is no ready-to-play scenario. Now the Referee can take the somewhat frugal examples and inspiration from them to develop a scenario, and similarly, take inspiration from the lengthy example of play that takes up the last quarter of the book. This is quite entertaining and shows the reader how the designer intends Kuf to be played.

The third greater problem is the broad nature of the game’s background. Gnosticism is the belief that human beings contain a piece of the highest good or a divine spark within themselves, and that both these bodies and the material world, having been created by an inferior being, are evil. Since it is trapped in the material world and ignorant of its status, this divine spark needs knowledge—‘gnosis’—in order to understand their true nature. This knowledge must come from outside the material world, which in Kuf is the other side of the barrier. At the same in Kuf, the Player Characters are protecting others from what lies on the other side of the barrier, and yet despite underpinning the roleplaying game, this deeper background is never really explored in Kuf. Perhaps the inclusion of a scenario or better yet, more threats, cults, creatures from beyond, and so on would have given scope for the designer to present this background in an accessible fashion.

Physically, Kuf is plain and simple, without any illustrations. It needs an edit, especially in the latter two thirds of the book.

Kuf works as a brutally nasty horror game—at least in mechanical terms, but does not quite work as a fully rounded, playable roleplaying game. If the Referee is looking for a modern day, grim and gritty horror roleplaying game using Old School Renaissance-style mechanics, then Kuf has the basics of everything she needs. If the Referee is looking for a modern day, grim and gritty horror roleplaying game with an interesting setting, then Kuf is not quite it. With some development (or even a second edition) Kuf could be the Gnostic horror game which the author envisioned, for its pages contain suggestions of it, tantalising the reader and the Referee like hints behind some kind of barrier, waiting the revelation which will reach out and touch that divine spark…

Protein is People!

What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? is a scenario designed for Metamorphosis Alpha: Fantastic Role-Playing Game of Science Fiction Adventures on a Lost Starship. The first Science Fiction roleplaying game and the first post-apocalypse roleplaying game, Metamorphosis Alpha is set aboard the Starship Warden, a generation spaceship which has suffered an unknown catastrophic event which killed the crew and most of the million or so colonists and left the ship irradiated and many of the survivors and the flora and fauna aboard mutated. Some three centuries later, as Humans, Mutated Humans, Mutated Animals, and Mutated Plants, the Player Characters, knowing nothing of their captive universe, would leave their village to explore strange realm around them, wielding fantastic mutant powers and discovering how to wield fantastic devices of the gods and the ancients that is technology, ultimately learn of their enclosed world. Originally published in 1976, it would go on to influence a whole genre of roleplaying games, starting with Gamma World, right down to Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic from Goodman Games. And it would be Goodman Games which brought the roleplaying game back with the stunning Metamorphosis Alpha Collector’s Edition in 2016, and support the forty-year old roleplaying game with a number of supplements, many which would be collected in the ‘Metamorphosis Alpha Treasure Chest’.

What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? is a scenario designed for Metamorphosis Alpha: Fantastic Role-Playing Game of Science Fiction Adventures on a Lost Starship. The first Science Fiction roleplaying game and the first post-apocalypse roleplaying game, Metamorphosis Alpha is set aboard the Starship Warden, a generation spaceship which has suffered an unknown catastrophic event which killed the crew and most of the million or so colonists and left the ship irradiated and many of the survivors and the flora and fauna aboard mutated. Some three centuries later, as Humans, Mutated Humans, Mutated Animals, and Mutated Plants, the Player Characters, knowing nothing of their captive universe, would leave their village to explore strange realm around them, wielding fantastic mutant powers and discovering how to wield fantastic devices of the gods and the ancients that is technology, ultimately learn of their enclosed world. Originally published in 1976, it would go on to influence a whole genre of roleplaying games, starting with Gamma World, right down to Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic from Goodman Games. And it would be Goodman Games which brought the roleplaying game back with the stunning Metamorphosis Alpha Collector’s Edition in 2016, and support the forty-year old roleplaying game with a number of supplements, many which would be collected in the ‘Metamorphosis Alpha Treasure Chest’.What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? takes a place on a forested deck of the Starship Warden. The Player Characters have spent a day or so exploring this forested deck and made camp, but when they wake up the next day, they hear the sounds of movement from a device of Ancients nearby. Going to check, they see a buggy with a cage full of prisoners travelling behind a robot being ridden by a mutant on its shoulders. The prisoners are pleading to be set free as the caravan proceeds towards a giant tree. When the Player Characters go to the aid of the prisoners—and they can get quite close using stealth—the caravan’s Mutant guards react quickly, allowing the buggy with its cargo of prisoners to race off into the giant tree.

After defeating the mutants, the Player Characters are free to follow the buggy and explore the giant tree, which it turns out is an elevator. Either by climbing down the deep elevator shaft or taking the elevator down, they only have access to the one level, some kind of factory producing green protein bars and guarded by a rag-tag band of Mutant guards. There is something quite horrid going on here and all too quickly, the Player Characters can discover the nature of the ingredients which go into these protein bars and who is behind it. The facility it turns out is Rec-Loc-119, which before the great calamity which befell the Starship Warden, was a biological reclamation facility which transformed biological matter into a protein rich food bar. As a result of the disaster, One-Nineteen, the now-sentient computer is determined to fulfil its programming, regardless of who has to die in the process. It has allied itself with the Mutants living in its facility and they have been conducting raids for fresh victims out on the forested deck above. With luck, the Player Characters can avoid the same fate that befell the previous prisoners, rescue the current prisoners, defeat One-Nineteen, and not eat too many green protein bars before they discover what they are made from!

What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? requires one of the Player Characters to be a Robot as it will be able to interface with One-Nineteen. These are not detailed in the standard rules for Metamorphosis Alpha, but come from the ‘Robots as Players in Metamorphosis Alpha’ article from Dragon #14. Alternatively, they can be found in the Metamorphosis Alpha Deluxe Hardcover Collector’s Edition. Another option would be for the Judge to include a Robot character as an NPC. It is suggested that the scenario be run for more experienced Player Characters and to reflect that, that they should gain a roll or two on the Technological and Mutated Substances Treasures Lists.

Physically, What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? is cleanly presented. The maps are excellent and the illustrations decently done. If there is an issue with the scenario, it is that its requirement for a Robot Player Character may not be possible for every playing group, and further, where many of the scenarios available for Metamorphosis Alpha are usually easily adaptable to other Post-Apocalyptic settings or roleplaying games, such as Mutant Crawl Classics, this is not case for this scenario. This is because not every Post-Apocalyptic setting or roleplaying game includes robots as a Player Character option or even robots at all. However, What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? does have scope for expansion onto the other floors accessible via the giant elevator, though at the time of the scenario, they are not accessible. Ultimately, What Are The Prisoners of Rec-Loc-119? is a nasty little dungeon with a big bad at the end. It is nicely detailed, with plenty of flavour, and would be easy to drop into an ongoing campaign.

Have a Safe Weekend

Friday Filler: Adventure Begins

It has been a while since there was mass audience boardgame designed to introduce Dungeons & Dragons. The original dungeoneering board from TSR, Inc. was of course, Dungeon!, most recently republished a decade ago. Before, there had been the 2010 Dungeons & Dragons: Castle Ravenloft Board Game, which would lead to a number of entries in the ‘Dungeons & Dragons Adventure System Board Games’ series, culminating in the 2019 Dungeons & Dragons: Waterdeep – Dungeon of the Mad Mage Board Game. All six entries in the series are themed around particular settings for Dungeons & Dragons and designed to introduce those settings as much as the basics of Dungeons & Dragons, including taking turns to be the Dungeon Master. There are elements of this in the latest board game for Dungeons & Dragons aimed at a family audience—Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins.

It has been a while since there was mass audience boardgame designed to introduce Dungeons & Dragons. The original dungeoneering board from TSR, Inc. was of course, Dungeon!, most recently republished a decade ago. Before, there had been the 2010 Dungeons & Dragons: Castle Ravenloft Board Game, which would lead to a number of entries in the ‘Dungeons & Dragons Adventure System Board Games’ series, culminating in the 2019 Dungeons & Dragons: Waterdeep – Dungeon of the Mad Mage Board Game. All six entries in the series are themed around particular settings for Dungeons & Dragons and designed to introduce those settings as much as the basics of Dungeons & Dragons, including taking turns to be the Dungeon Master. There are elements of this in the latest board game for Dungeons & Dragons aimed at a family audience—Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins.Published by Wizards of the Coast, is a co-operative, streamlined Dungeons & Dragons-themed board game designed for two to four players, ages ten and up. In it, four heroes will journey across four regions—Gauntlgrym, Mount Hotenow, Neverwinter Wood, and Neverwinter itself—and in the last of these face a Boss monster, either Felbris the Beholder, Orn the Fire Giant, Deathsleep the Green Dragon, or the Kraken. The four heroes—Korinn Nemmonis, a Dragonborn Rogue, Kiya Astorio, a Human Sorcerer, Thia Silverfrond, an Elf Bard, and Tak Strongheart, a Dwarf Fighter—will face different dangers in each location, including a gatekeeper encounter which must be defeated before they can go on to the next location, and their players have opportunities to decide what paths to take, which options to take in terms of what attacks their Heroes can perform, be a little creative here and there, and even take a turn being the Dungeon Master.

Each of the four Heroes consists of three tiles, which slot into a plastic health tracker with a slide. The three tiles are the Hero Tile, which gives the name, Race, and Class, and the Personality Tile and the Combat Tile. All are double-sided. The two sides for the Hero Tile are male and female, but the Personality Tile and Combat Tile provide a personality type and a special ability, and different attacks respectively. The Combat Tile can also be flipped to indicate when a Hero has risen from First Level to Second Level, and so gets better attacks. By changing around the Personality Tile and the Combat Tile, a player can customise his Hero, if only a little.

The game is played on four dungeon boards—Gauntlgrym, Mount Hotenow, Neverwinter Wood, and Neverwinter—that connect one after the other to form a zig-zag. They can be placed in any order, though the last one will contain the Big Boss which the players and their Heroes must defeat to complete the quest. Each dungeon board is marked with a core path consisting of four spaces, three Core Spaces with a Gatekeeper Space at the end. There are two Monster Spaces to the side which the Heroes can divert to if they and their players want to face more monsters and potentially, gain more gold. Each dungeon board also has its own adventure deck, consisting of twenty-four cards, which are either scenario cards or monster cards. The first presents a narrative and a challenge to be overcome, and the second a monster which has to be defeated.

Both play and set-up are quick and easy. Each player selects a Hero and choses which Personality Tile and the Combat Tile his Hero will have. The Big Boss is chosen and the appropriate dungeon board is placed last, with the others connected to it in a random order. Each Adventure Deck is shuffled and placed next its board. There is a plastic deck holder which is used for each Adventure Deck when the Heroes are on the associated dungeon board. Each Hero has its own nicely detailed miniature and a twenty-sided die in the same colour, which placed together on the first Core Space on the first dungeon space. One player will also take the role of the Dungeon Master and roll for the monster attacks—using a ten-sided die instead of the twenty-sided die that each player rolls, which means that the one player will control both a Hero and be the Dungeon Master for the dungeon board. The role of Dungeon Master switch to the next player when the Heroes progress onto the next dungeon board.

From one turn to the next, the Heroes progress along the Core Path on the Dungeon Board, with the Dungeon Master drawing cards from the Adventure Deck. This is done collectively, but Heroes can also take side paths onto Monster Spaces. They can do this together or singularly, but must defeat the monster before carrying on, and if some of the Heroes decide to remain on the Core Path whilst the others monster hunting, they have to wait for them to catch up before everyone can continue. Although fighting monsters means potentially losing Hit Points, if the Heroes win, they can gain more gold. Gold is important because it can be spent to purchase items, level up from First to Second Level, and defy death and re-join play if their Hit Points are reduced to zero.

Combat in Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins is greatly simplified in comparison to Dungeons & Dragons. A player rolls for his Hero against the table on his Hero’s Combat Tile with a twenty-sided die, whilst the Dungeon Master rolls on the table on the monster card with a ten-sided die, which will determine the type of attack made and the amount of damage rolled. For example, Undead Townspeople miss on a roll of one to four, but inflict one point of damage with assorted utensils with a roll of five or more, whereas a Hero and his player always has a choice of three—a combination of two weapon and spell attacks, and a move or creative attack. For example, Thia Silverfrond, the Elf Bard, could fire an arrow with his shortbow for a point of damage as the weapon attack, break out into hideous laughter for two damage as a spell-like attack, or create a Theatrical Distraction to get the monster’s attention using a musical instrument or an item from his backpack. If successful, the Theatrical Distraction either inflicts two points of damage or just the one, in which case, the attack also stuns the monster and prevents it from attacking that round. A roll of a natural twenty also inflicts an extra point of damage.

Once the Heroes reach the last space on the dungeon board, the Gateway Space, they must face a tougher monster or challenge, whilst the Big Boss at the end is tough with multiple different attacks and lots of Hit Points. Every Big Boss comes with some text to read out when it is defeated, which brings the game to a close Of course, by the time the Heroes get to that point, they should ideally have accrued enough gold to boost themselves to Second Level, which also has the added benefit of restoring a Hero’s Hit Points to full.

As a version of Dungeons & Dragons, there can be no doubt that Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins is greatly simplified. Mostly obviously in the singular path that the Heroes have to take in progressing from one dungeon board to the next to reach the Big Boss, but the Dungeon Master’s role is really reduced to rolling attacks randomly rather than choosing them. On the other hand, the players are presented with choices—simple ones, but choices, nonetheless. Again most obviously, in choosing which of the three attacks his Hero can use and whether or not to deviate from the Core Path to a Monster Space and there face an enemy in combat. Yet there is another choice too, one which encourages a little bit of creativity upon the part of the player. The creative attack calls for the player to describe how his hero uses items from his backpack, whether from the backpack chosen at the start of the game, or an item purchased during play, and that calls for some inventiveness. When that works—and sometimes what it does not work—that adds a bit of story to the play of Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins as well to the Hero himself. There at least you have the basics of roleplaying found in Dungeons & Dragons present in this game.

However, there are issues with just how many times Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins can be replayed before it gets stale. Now every Hero has two options in terms of both the special ability on the Personality Tile and the various attacks on the Combat Tile, and with twenty-four cards in the Adventure Deck for each dungeon board, there is a reasonable mix to be found there. With just four Big Bosses and a limited number of Gateway Cards, there is less variability in the end of level bosses to be encountered. Another issue is that the game plays better with all four Heroes, so it is best with four players, or fewer players sharing the Heroes. Other options might be for a parent to be the Dungeon Master whilst her children play the Heroes, or even a player take on the game in solitaire mode.

Physically, Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins is decently done and of a reasonable quality. The miniatures are nice, and having colour-coordinated with the dice is a nice touch. Having the plastic stands for both the Heroes, the Adventure Deck, and the Big Bosses also adds a physical presence to the game.

For the experienced gamer, whether he plays Dungeons & Dragons or not, Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins is at best a mild diversion, at worst simplistic. Yet for a younger audience or a family audience, especially one interested in Dungeons & Dragons or roleplaying, this is decent first step. There are some clever little elements in Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins which encourage a creativity and inventiveness without making things any more complex. It would be interesting to see a sequel, Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Continues, but Dungeons & Dragons: Adventure Begins is a serviceable start.

The Aftermath: March 2022 Open House the Third

Friday Fantasy—Corpsewake Cove

The pirates came to your village and unleashed bloody murder and chaos upon your home. They killed your dog, Boris, and stole his embroidered collar. They beheaded your mother and stole her head. They left your grandparents blind and salted the family farm. They kidnapped your sibling and forced them into servitude. They stole the Sword of Vengeance, your responsibility and your birthright. They slaughtered all of the village’s livestock and used their corpses to foul the village well. They were joined in plundering your village by your best friend, and now he has joined them. They ruined your life, your home, and your future. Now you want your revenge. You know the pirates sailed out of their thoroughly wretched hive of scum and villainy, Corpsewake Cove, and now you plan to sneak in and have your bloody vengeance. You do not know who led the raid upon your village, but Corpsewake Cove is ruled by a council of five Pirate Kings, so better to kill them all. It does not matter your name, but they had better prepare to die, whether you assassinate them one by one, or simply put them to the sword!

The pirates came to your village and unleashed bloody murder and chaos upon your home. They killed your dog, Boris, and stole his embroidered collar. They beheaded your mother and stole her head. They left your grandparents blind and salted the family farm. They kidnapped your sibling and forced them into servitude. They stole the Sword of Vengeance, your responsibility and your birthright. They slaughtered all of the village’s livestock and used their corpses to foul the village well. They were joined in plundering your village by your best friend, and now he has joined them. They ruined your life, your home, and your future. Now you want your revenge. You know the pirates sailed out of their thoroughly wretched hive of scum and villainy, Corpsewake Cove, and now you plan to sneak in and have your bloody vengeance. You do not know who led the raid upon your village, but Corpsewake Cove is ruled by a council of five Pirate Kings, so better to kill them all. It does not matter your name, but they had better prepare to die, whether you assassinate them one by one, or simply put them to the sword!This is the set-up for Corpsewake Cove, a tale of romance and revenge—but really mostly revenge, in which the Player Characters sneak into the spumous seaside settlement, investigate the town, and take what opportunity they can. Published by Ember + Ash following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it is a Mörk Borg compatible scenario which presents everything to explore a pirate town all but hanging from a cliff over a cove in which swims the Frankenshark, a harbour at which the five singular ships of the five Pirate Kings are docked, write-ups of the five Pirate Kings and their crews, various NPCs and locations, plots, and a countdown to disaster which will come to pass come the end of the week.

For the Player Characters, Corpsewake Cove begins with their being in the tavern. Grieving over their loss, they are rueful and revenge-filled, deciding how best to take it upon the men and women who caused it. An ex-pirate, Bunket, shares with the Player Characters what he knows of the Pirate Kings, Corpsewake Cove, and what approaches he might have had he sworn bloody vengeance on a bunch of bloodthirsty and brutal pirates and their even more terrible masters. Three alternatives are included if the players do not want their characters to be motivated by revenge: Bounty Hunter, Treasure-Crazed Lunatic (because where there are pirates, there is always treasure), and Dewy-Eyed Pirate Wannabe. These come with a bit of background and a flavoursome list of equipment. Whichever motivation chosen, Corpsewake Cove will still rely upon the various character Classes given in Mörk Borg, Mörk Borg Cult: Feretory, and Mörk Borg Cult: Heretic, which does feel slightly odd, in that the Player Characters are almost as wretched, if not more so, than the pirates of Corpsewake Cove. Of course, they are not as scurvy, but this definitely a scenario involving the wretched versus the wretched!

For the Game Master, there is a useful list of pirate slang, a timeline of events whilst the Player Characters in Corpsewake Cove, details of each of the Pirate Kings’ ships—differentiated by colour, no less!, full write-ups for all five Pirate Kings—again colour coded, a description of the curse which besets the bay and town (because pirates and curses go together like rhubarb crumble and custard), and then a tour of all fourteen locations in the town. All of these are crammed up the face of the cliff and include the Ruddy Wren, a fine old house subdivided into horridly unpleasant little rooms rented out for the night, though upstairs rooms are available and the downstairs ones strangely locked; Jack’s Pulpit, a bloody bare knuckle fight ring overlooked by a ‘pet’ manticore chained to a wall; and St. Delphin’s, the town’s church, overseen by a priest distraught at the godless state into which the town has fallen! There are locations underneath the town too, and an array of weird monsters, all with a piratical theme. The most include the Soggy Zombie Pirates, One Good Rat Boy (ordinary rat, but the size of a child), Deranged Seagulls (aren’t they all?) with weaponised poop, a ship’s figurehead which animates almost Kaiju-like, and an actual Ex-Parrot! Lastly, there is a set of tables for generating pirate names, traits, and attire and equipment, useful because, well, Corpsewake Cove is full of pirates (and zombie pirates).

Corpsewake Cove is designed to be Player Character driven. They will probably move into the pirate port and find a place to stay before beginning to monitor the activities and movements of the five Pirate Kings. This will involve visiting locations and in the process interacting with the inhabitants of Corpsewake Cove and hopefully begin to have some idea as to the plots going in the background—some of which they might use to their advantage. The Pirate Kings will go about their activities as normal, including sailing in and out of the port on raids as time passes by. Although each of the Pirate Kings is described in detail, what the scenario does lack is advice as to what they do once the Player Characters begin taking their revenge and killing their fellow captains.

Physically, Corpsewake Cove takes its cue from Mörk Borg, but barring the acid yellow, tends towards less vibrant shades. Although it requires a slight edit in places, it is in general well written. It does need a slight reorganisation in places as the underground locations feel as if they are in the wrong order.

Corpsewake Cove offers opportunities for exploration and interaction and weirdness—as you would expect for a Mörk Borg scenario, but its ultimate path is one to blue bloody murder and revenge. How the Player Characters go down this path is up to their players and their cut of the jib, and more than half the fun!

Gary Con 2022 Bound!

Random RPG Thoughts

Have a bunch on my plate at the day job right now and I am headed up the Gary Con tomorrow and the weekend. The best part of Gary Con? I can drive in, drive out, and sleep in my own bed every night!

Unnamed Victorian/Rural Gothic Mini-campaign

I want to run an adventure/campaign set in Victorian times and combine "Little House on the Prairie" with "True Detective" Season 1 and Carcosa. Essentially you are all a bunch of gritty detectives and have chased this dangerous "End times" cult to the US Midwest in the 1880s.

This cult had a member that is a bit clairvoyant and saw World War I and decide that it is better to end the world. She went mad (naturally) and this is how the PCs discover the cult's activity and connects them to a string of grisly sacrificial murders.

Why Little House? Well I did enjoy the show growing up and it seems so idyllic, even with their hardships, and some cult trying to draw down some horror beyond the stars is so incongruous to the setting that it makes for its own first level of horror.

Originally this was called "Ghosts of Albion: Carcosa" but today I could use pretty much any Victorian-era system for it. I have all of them.

New Gaming Gear

My youngest is now in college and has built a new computer. So I just got a "hand-me-down" Alienware. With this and my other gaming computer, I am thinking about getting some new PC games to play. All of the old AD&D "Gold Box" games are coming to Steam. I never had the time to play them when they were new but I am hoping they might scratch that AD&D 2nd Ed itch I have.

ETA: Just found another hard drive to put in it!

Sci-Fi RPGs

I have been in the mood for a sci0fi RPG for some time. Now my oldest is too. Though he wants something that is compatible with 5e so he can continue playing in his world and doesn't want to go the Starfinder ("Featfinder") route. Ultramodern5 has been suggested to me as has Esper Genesis.

This is only quasi-related to my Star Trek games. Though it will inform my choices when I do Sci-Fi month in May.

Spell Database

Not for publication, just my own use. I am putting together a database of every spell I have written for all my witch books. While I am not expecting to share this out, you will likely see the products of the labor one day.

Monster Books

With the day job, I have not had much of a chance to really work on any of these. In fact, my last edit was early February according to the file dates. Hope to get back on these.

Review: Tome of the Unclean (Castles & Crusades)

Last week I spent a lot of time with the Castles & Codex series and it was great fun. But there is another book that also works well with my universe building and it is not about the gods. Rather quite the opposite.

Last week I spent a lot of time with the Castles & Codex series and it was great fun. But there is another book that also works well with my universe building and it is not about the gods. Rather quite the opposite.Back in October of 2017 Troll Lords launched their Tome of the Unclean Kickstarter. With the idea to bring demons, devils, and other fiends to the Castles & Crusades game. It would also work with Amazing Adventures (which is what I would end up doing later). I was immediately hooked and knew I needed this book.

Fast forward to 2019 I got my book in the mail and I had been picking up the PDFs (they released as they were completed starting in Jan 2018) all throughout.

I have just been really slow at getting my review up.

For this review, I am considering both the hardcover print version from the Kickstarter and the now final PDF from DriveThruRPG.

144 pages. Color covers, black & white interior art.

The book follows a format that is now common to many books about fiends. A part that deals with Demons and Lords of the Abyss. Another that covers Devils and the Legions of Hell. And a third, which often differs from book to book, covers other fiends of Gehenna and the Undead. Adding in the undead is a nice touch in my mind and a value add for the book.

Demons & Devils

This covers the basic differences and how these creatures fit into the World of Aihrde, the game world of Castles & Crusades. It also covers the basics of the monster stat block.

Lords of the Abyss

This is our section about Demons and the Abyss. It cleaves pretty close to the AD&D standard with what I often refer to as "the Usual Suspects," so all the "Type" demons and succubi. The new material here includes Abyssal Oases which are areas that are habitable by mortal-kind that seem to come up at random.

Covered here are also traits about the Abyss and powers and traits common to all demons.

The monsters are all alphabetical, so common demons are not separated from the lords. There are a few lords present. Demogorgon and Orcus return. But also Oozemandius (as a Juiblex stand-in) and Buer. Graz'zt is mentioned a few times, but no stats are given. There are 32 total demons with four as lords.

Legions of Hell

This section follows a pattern similar to the Demons one. The Hells are described, including the nine layers. They have some new names and some differences, but if you are wed to the Ed Greenwood Dragon articles about Hell then there is not a lot to convert here.

There are 53 devils, with 16 of these listed as unique Arch-Devils. There are more new devils here than there are new demons.

Gehenna

This is our "Neutral Evil" plane in the Great Wheel cosmology of the world of Aihrde, taking the place of Hades or the Grey Wastes from AD&D. This is home to the daemons. Like the previous chapters, this covers the features of the land and it's inhabitants. Reading through it is feels like equal parts of the Greek Hades and the Underworld of Kur in the Babylonian myths where Ereshkigal rules.

Only four deamons are detailed here, with one, Charon the Boatman, as the only unique member.

Undead

The name of the book is the Tome of the Unclean. While demons and devils take up the vast majority of the book there is still some space for the Undead.

18 undead creatures are detailed here, most of favorites (but creatures Vampires are missing) and some new ones.

Denizens. Fauna, & Flora

Covers various types of evil, non-fiendish, non-undead, monsters that can also be found.

We end with Aihrde specific information and our OGL page.

Tome of the Damned is a fantastic resource for anyone wanting more information on demons, devils, and their ilk for anyone playing Castles & Crusades. In fact, if you are playing C&C and want demons then this is a must-have book.

The advantage of Castles & Crusades is that it can be adapted to AD&D or any OSR game easily. So if you want more than what the Monster Manuals I & II can give you, then this book is also a good choice. I f you are playing AD&D 2nd ed then this book will fill in many of the gaps left by that game.

Now, I have an entire library of books dedicated to demons, devils, and all sorts of evil monsters. There were only a few things here actually new to me. But I still rather enjoyed this book quite a lot. It is a good addition to my Castles & Crusades library.

Monstrous Mondays: The AD&D 2nd Ed Monstrous Compendiums, Part 6

Back to the business at hand. Today will cover the "others" in my Monstrous Compendium collections, but not ones I used regularly. Again the time these came out money was tight for a college kid needing to buy school supplies, food, and pay rent so choices were made. Ravenloft won, Dark Sun and Spelljammer lost.

Back to the business at hand. Today will cover the "others" in my Monstrous Compendium collections, but not ones I used regularly. Again the time these came out money was tight for a college kid needing to buy school supplies, food, and pay rent so choices were made. Ravenloft won, Dark Sun and Spelljammer lost. Thankfully these days I can buy PDFs much cheaper and with little to no concern for storage space. Plus I have recently begun to explore Spelljammer and I have found it to be rather fun.

For these reviews, I am considering the PDFs only. I have the published ones, but not all of them, and the one I do have (Spelljammer 1) is incomplete. No idea why.

MC7 Monstrous Compendium Spelljammer Appendix

PDF 64 pages (70 with dividers and covers), Color cover art, black & white interior art, $4.99. 64 monsters.

There was/is something very cool about the Spelljammer monsters. First, they were not afraid to try something new here. Which I like. Secondly, there are also some odd-balls here like the Giant Space Hamster. Oh well, you have to have some fun. There are some Star Frontiers aliens analogs here, so that made cross-overs a fun idea, but I have no idea if anyone ever did any.

MC9 Monstrous Compendium Spelljammer Appendix IIPDF 64 pages (70 with dividers and covers), Color cover art, black & white interior art, $4.99. 61 monsters.

Like the first Spelljamer MC this one gives us some fairly unique and interesting monsters. The one I recall the best is the Scro or the "Space Orcs." We also get a trio of celestial dragons which is fun.

There is also a collection of MC-formated monsters in the Spelljammer: Adventures in Space set.

MC12 Monstrous Compendium Dark Sun Appendix: Terrors of the Desert

PDF 96 pages, Color cover art, black & white interior art, $9.99. 92 monsters.

Moreso than any other campaign world, Dark Sun is the most foreign to me. I *like* the idea of it. I have even since adopted some of the notions of it into my regular game world. Plus there is a solid message here; exploit the environment and eventually, you will screw it up for everyone. But many of the monsters are very new.

This MC does adopt a different accent color for the pages. A nice touch that again I would have liked to have seen for all the others. Pretty much all of these creatures are new for me. I would like to use them in a desert game, but I think a few might be a bit of work to remove them from their background.

Dark Sun Monstrous Compendium Appendix II: Terrors beyond Tyr

PDF 128 pages, Color cover art, color interior art, $9.99. 105 monsters.

This one was published as a softover volume. It follows closer to the Dark Sun trade dress as opposed to the Monstrous Compendium one. This does mean that monster pages are full color.

Interestingly enough for me, this one has monsters I am more familiar with. Also, given the nature of the campaign world, many of these creatures can be used as player characters. So details are given for that.

The One Ring II Starter

It was with no little disappointment that Cubicle Seven Entertainment announced in November, 2019 that it would no longer be publishing The One Ring: Adventures Over The Edge Of The Wild, the hobby’s fourth and most critically acclaimed attempt to create a roleplaying game based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Originally published in 2011, fans had been looking forward to the second edition of the game, which was being worked on at the time of the announcement. When in 2020, Swedish publisher, Free League Publishing—best known for Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the '80s That Never Was, Alien: The Roleplaying Game, and Symbaroum—announced that it had acquired the licence, there was some concern that its forthcoming edition would be based on its Year Zero mechanics. The good news is that following a successful Kickstarter campaign, The One Ring, Second Edition not only retains its original design and writing team, but also the same mechanics—with some updates, and it receives its very own starter set.

It was with no little disappointment that Cubicle Seven Entertainment announced in November, 2019 that it would no longer be publishing The One Ring: Adventures Over The Edge Of The Wild, the hobby’s fourth and most critically acclaimed attempt to create a roleplaying game based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Originally published in 2011, fans had been looking forward to the second edition of the game, which was being worked on at the time of the announcement. When in 2020, Swedish publisher, Free League Publishing—best known for Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the '80s That Never Was, Alien: The Roleplaying Game, and Symbaroum—announced that it had acquired the licence, there was some concern that its forthcoming edition would be based on its Year Zero mechanics. The good news is that following a successful Kickstarter campaign, The One Ring, Second Edition not only retains its original design and writing team, but also the same mechanics—with some updates, and it receives its very own starter set.The One Ring Starter Set provides both an introduction to the roleplaying game and everything necessary to begin a short campaign. Inside the sturdy box can be found three booklets—the twenty-four-page Rules booklet, the fifty-two page The Shire booklet, and the thirty-one page The Adventures booklet, a set of double-sided character sheets for eight pre-generated Player Characters, two large maps showing the Shire and Eriador, and two sets of play aids which can be used The One Ring, Second Edition core rules. These consist of a deck of thirty Wargear Cards and six double-sided Journey Role and Combat Stance Cards. Lastly, there is a set of eight dice, which include two Feat dice.