Outsiders & Others

1980: Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was published by Fantasy Games Unlimited in 1980 and has the distinction of being the first roleplaying game set in the Ancient World. It is a roleplaying game in which heroes of the age adventure, travel the known world and sail the Aegean Sea and beyond, battle heroes from other lands, and maybe face the monsters that lurk in the seas and caves far from civilisation. It is also a man-to-man combat system, a trireme-to-trireme combat system, a guide to a combination of Greece in the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, and all that packed into thirty-two pages. However, it is very much a roleplaying of its time and vintage—and what that means is there is at best a brevity to game, a focus on combat over other activities, and a lack of background to the setting. Now of course, many of the gamers who would have played Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age in the early nineteen eighties—just as they are today—would have been knowledgeable about the Greek Myths and so been able to flesh out some of the background. However, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age still leaves the Moderator—as the Game Master is known in Odysseus—with a lot of work to do.

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was published by Fantasy Games Unlimited in 1980 and has the distinction of being the first roleplaying game set in the Ancient World. It is a roleplaying game in which heroes of the age adventure, travel the known world and sail the Aegean Sea and beyond, battle heroes from other lands, and maybe face the monsters that lurk in the seas and caves far from civilisation. It is also a man-to-man combat system, a trireme-to-trireme combat system, a guide to a combination of Greece in the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, and all that packed into thirty-two pages. However, it is very much a roleplaying of its time and vintage—and what that means is there is at best a brevity to game, a focus on combat over other activities, and a lack of background to the setting. Now of course, many of the gamers who would have played Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age in the early nineteen eighties—just as they are today—would have been knowledgeable about the Greek Myths and so been able to flesh out some of the background. However, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age still leaves the Moderator—as the Game Master is known in Odysseus—with a lot of work to do.A hero in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age—and it is very much a case of it being a hero rather than a hero or a heroine, is a young warrior ready to set out on a life of adventure and myth building. Aged between seventeen and twenty-three, he is defined by his home province, which also determines his patron god, his lineage, which determines his primary profession—which he shares with father, and his other skills. Rolls are also made for his family and the armour he begins play with. Notably, a hero has the one skill or ability—his Fighting Skill Number or FSN, initially rated between eleven and twenty, and can go higher. As well as Fighting Skill Number, a player also rolls for his hero’s armour—type, what it covers, and its composition. Heroes with a high FSN are likely to have better, even iron, armour.

Alastair

Age: 23

Home Province: Messenia

Patron God: Hephaestus

FSN: 20

Skills: Accountant (Major), Barber, Architect

Family: Only son, father deceased

Armour: Type II Body Armour (bronze torso and shoulders, greaves, and aspis)

Arms: Shortsword, spear, bow & twenty arrows

So character generation out of the way—although as we shall see, it is not complete—Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age dives not into the mechanics of a skill system (there is none) or the man-to-man ‘combats’ system (as it is described), but the rules for ship-to-ship combat. They describe Greek naval warfare as complex and are essentially a miniatures combat system, for which it is suggested that a large floor space and miniatures are needed. The rules cover movement—by sail and by oars, as well as the effect of the wind, maneuvering, missile fire—from both arrows and spears, collisions and ramming, plus grappling and boarding, taking on water, mast damage, and more. All of this is done in the captain’s orders, which are written down at the beginning of every combat round. The rules cover everything in just three pages.

Man-to-man combat or ‘Combats’ as Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age describes it, is actually more complex than ship-to-ship combat. Initiative is generally handled by weapon range—weapons with longer range or reach indicating that a warrior attacks first. Then each combatant selects two cards, one an Attack Position Card, the other a Defence Position Card. The Attack Position Card indicates where the attacking warrior intends to strike, for example Head, Abdomen, or Calf, whilst the Defence Position indicates where the defending warrior wants to protect, for example, ‘Parry Middle Without Shield’ or ‘Punch with Shield High’. The chosen Attack Position Card and Defence Position Card are cross referenced on the ‘ATK POS/DEF POS’ table. This can generate an ’NE’ or ‘No Effect’ result, in which case the attack is blocked or the attacker missed, or it can generate a modifier which is applied to the chance to hit number. This is determined by cross referencing the weapon used in the attack against the protection value of the armour on the location struck. This is a percentage value under which the attacking player must roll to succeed. Conversely, the player needs to roll high on the percentage dice to determine how much damage is inflicted, which determined by the Attack Position—as determined by the Attack Position Card cross referenced with the roll, the result varying from ‘No Effect’, ‘Stun’, and one or more Wounds to ‘Kneeling’, ‘Unconscious’, and ‘Kill’.

So the question is, where does a warrior’s Fighting Skill Number come into this if it is not being used to determine whether or not he successfully attacks or defends? Well, it does two things. First, it acts as a warrior’s Hit Points, with points being deducted equal to the number of Wounds suffered. Second, for each five points or part of, a warrior’s Fighting Skill Number is ten or above, he gains an extra attack each round. So between ten and fourteen points, a warrior has two attacks, three attacks for between fifteen and nineteen, and four attacks for twenty and above. When a warrior suffers Wounds and his Fighting Skill Number is reduced, if drops past the threshold, so does his number of attacks per round. Although a Warrior’s Fighting Skill Number can rise above twenty by being a successful combatant, the maximum number of attacks he can make is four. Thus points in Fighting Skill Number above twenty four represent just his Hit Points.

Beyond the mechanics for ship-to-ship combat and man-to-man combats, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age includes some campaign notes for the Moderator, primarily movement and encounters—by land and by sea, and done daily. The encounter table includes some classic mythic creatures like Gorgons and Centaurs, but essentially, they have no more stats than Player Character. All of the encounters are accorded thumbnail descriptions, as are the gods. The only major piece of advice for the Moderator is how to handle warrior versus god combat, that comes down to allowing it, but inflicting a high degree of bad luck upon the warrior for being so presumptuous!

There are two other mechanics in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age and both concern the Player Characters, but both are secret. In fact, they are so secret that the Moderator rolls them and never reveals them to his players. Both are straight percentage values. One is the Deity Empathy Score, which reflects how much a warrior’s patron likes or dislikes him, whilst the other is the warrior’s Luck Number. The only suggested use for this is determining how well other people react to the warrior.

In terms of background, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is very lightly written, its treatment of the Homeric Age very broad. Oddly, warriors cannot be from Crete or Troy, the choice of weapons is limited, and there is very little historicity to the whole affair. There are also some oddities in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age. The first is that the example of play appears on the book’s last page. The second is that in the middle of rules there is a quiz about the rules. Which is very probably unique in the history of the hobby. The third is that given its vintage, it is surprising that Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age does not explain what roleplaying is, but that it does not explain what a Moderator really does either.

Physically, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is a slim book with rather underwhelming production values. Although the pen and ink illustrations are really quite good, the maps are bland and lack detail. It needs another edit and it is not quite sure what the title is—Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age, Odysseus the Wanderer, or Odysseus Legendry & Mythology (sic). The main issue perhaps is the odd organisation which dives in ship-to-ship combat before personal combat, in the inclusion of a pop quiz about the rules rather than more examples of play, and so on. The game includes a card insert which is intended to be removed and used in play, and includes the Attack Position Cards and Defence Position Cards, and two ship’s deckplans.

—oOo—

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was reviewed by Elisabeth Barrington in Space Gamer Number 31 (September, 1980), who commented that, “The character generation rules are a little skimpy at times, and some of the numerous tables are difficult to figure out.” before concluding that, “As new RP systems go, this one is above average. Only one book, and it is well-designed. Historical gamers specialising in the classic period, this is for you.” However, Donald Dupont, writing in Different Worlds Issue 11 (Feb/Mar 1981) was far less positive, opening with the comment, “Odysseus is apparently an attempt at a roleplaying system for the Homeric Age of Greece, the Heroic Age of which Homer sings in his epics Iliad and Odyssey. As a mise en scene for the Bronze Age in the Aegean Basin it fails miserably. As a role-playing system it is disorganized, clumsy, and incomplete. The game lacks color, both of the Homeric Age, which it claims in its title, and of the later Classical Age which, in fact, it more closely approximates.” He finished the review by saying that, “Odysseus is a disappointment. The roleplaying world could use a good Heroic Age game system. With a great deal of interpretation and interpolation, Odysseus is perhaps usable by players familiar with role-playing systems, but the confused nature of its rules, and the lack of color in its world hardly make it worthwhile.”

—oOo—

It is debatable whether Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is a roleplaying game, its wargaming origins being so evidently on show, its focus being mainly on combat, and there being very little in terms of character to either roleplay or develop. This is not to say that the game cannot be played as either a wargame or a roleplaying game, but it would require a great deal of input from both player and Moderator—especially the Moderator, and whatever roleplaying experience might ensue, would definitely come from their efforts rather than be supported by the game itself. Of course, there are many roleplaying games like this, and this is with the benefit of hindsight, but even then, there really is very little to recommend Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age. It simply does not have the right sort of rules to be a roleplaying game and it does not have the background to really do what the author intended. Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is very much a collector’s curio, a design from the beginning years of the hobby when not every publisher quite knew what a roleplaying game should be or what it should do, a design still influenced too much by the wargaming hobby before it.

[Free RPG Day 2020] Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.Published by Magpie Games, Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is a roleplaying game based on the award-winning Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, about conflict and power, featuring struggles between cats, birds, mice, and more. The Woodland consists of dense forest interspersed by ‘Clearings’ where its many inhabitants—dominated by foxes, mice, rabbits, and birds live, work, and trade from their villages. Birds can also be found spread out in the canopy throughout the forest. Recently, the Woodland was thrown into chaos when the ruling Eyrie Dynasties tore themselves apart in a civil war and left power vacuums throughout the Woodland. With no single governing power, the many Clearings of the Woodland have coped as best they can—or not at all, but many fell under the sway or the occupation of the forces of the Marquise de Cat, leader of an industrious empire from far away. More recently, the civil war between the Eyrie Dynasties has ended and is regroupings its forces to retake its ancestral domains, whilst other denizens of the Woodland, wanting to be free of both the Marquisate and the Eyrie Dynasties, have formed the Woodland Alliance and secretly foment for independence.

Between the Clearings and the Paths which connect them, creatures, individuals, and bands live in the dense, often dangerous forest. Amongst these are the Vagabonds—exiles, outcasts, strangers, oddities, idealists, rebels, criminals, freethinkers. They are hardened to the toughness of life in the forest, but whilst some turn to crime and banditry, others come to Clearings to trade, work, and sometimes take jobs that no other upstanding citizens of any Clearing would do—or have the skill to undertake. Of course, in Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, Vagabonds are the Player Characters.

Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’, the mechanics based on the award-winning post-apocalyptic roleplaying game, Apocalypse World, published by Lumpley Games in 2010. At the heart of these mechanics are Playbooks and their sets of Moves. Now, Playbooks are really Player Characters and their character sheets, and Moves are actions, skills, and knowledges, and every Playbook is a collection of Moves. Some of these Moves are generic in nature, such as ‘Persuade an NPC’ or ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’, and every Player Character or Vagabond can attempt them. Others are particular to a Playbook, for example, ‘Silent Paws’ for a Ranger Vagabond or ‘Arsonist’ for the Scoundrel Vagabond.

To undertake an action or Move in a ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, a character’s player rolls two six-sided dice and adds the value of an attribute such as Charm, Cunning, Finesse, Luck, or Might, or Reputation, to the result. A full success is achieved on a result of ten or more; a partial success is achieved with a cost, complication, or consequence on a result of seven, eight, or nine; and a failure is scored on a result of six or less. Essentially, this generates results of ‘yes’, ‘yes, but…’ with consequences, and ‘no’. Notably though, the Game Master does not roll in ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game.

So for example, if a Player Character wants to ‘Read a Tense Situation’, his player is rolling to have his character learn the answers to questions such as ‘What’s my best way out/in/through?’, ‘Who or what is the biggest threat?’, ‘Who or what is most vulnerable to me?’, ‘What should I be on the lookout for?’, or ‘Who is in control here?’. To make the Move, the player rolls the dice and his character’s Cunning to the result. On a result of ten or more, the player can ask three of these questions, whilst on a result of seven, eight, or nine, he only gets to ask one.

Moves particular to a Playbook can add to an attribute, such as ‘Master Thief’, which adds one to a character’s Finesse or allow another attribute to be substituted for a particular Move, for example, ‘Threatening Visage’, which enables a Player Character to use his Might instead of Charm when using open threats or naked steel on attempts to ‘Persuade an NPC’. Others are fully detailed Moves, such as ‘Guardian’. When a Player Character wants to defend someone or something from an immediate NPC or environmental threat, his player rolls the character’s Might in a test. The Move gives three possible benefits—‘ Draw the attention of the threat; they focus on you now’, ‘Put the threat in a vulnerable spot; take +1 forward to counterstrike’, and ‘Push the threat back; you and your protected have a chance to manoeuvre or flee’. On a successful roll of ten or more, the character keeps them safe and his player cans elect one of the three benefits’; on a result of seven, eight, or nine, the Player Character is either exposed to the danger or the situation is escalated; and on a roll of six or less, the Player Character suffers the full brunt of the blow intended for his protected, and the threat has the Player Character where it wants him.

The release for Free RPG Day 2020 for Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart. It includes an explanation of the core rules, six pregenerated Player Characters or Vagabonds and their Playbooks, and a complete setting or Clearing for them to explore. From the overview of the game and an explanation of the characters to playing the game and its many Moves, the Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is well-written. It is notable that all of the Vagabonds are essentially roguish in nature, so in addition to the Basic Moves, such as ‘Figure Someone Out’, ‘Persuade an NPC’, ‘Trick an NPC’, ‘Trust Fate’, and ‘Wreck Something’, they can ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’. This covers Acrobatics, Blindside, Counterfeit, Disable Device, Hide, Pick Lock, Pick Pocket, Sleight of Hand, and Sneak. Each of these requires an associated Feat to attempt, and each of the six pregenerated Vagabonds has one, two, or more of the Feats depending just how roguish they are. Otherwise, a Vagabond’s player rolls the ‘Trust to Fate’ Move.

The six pregenerated Vagabonds include Ellora The Arbiter, a powerful Badger warrior devoted to what she thinks is right and just; Quinn The Ranger, a rugged Wolf denizen who left the Woodland proper to escape the war and their past as an Eyrie soldier; Scratch The Scoundrel, a Cat troublemaker, arsonist, and destroyer; Nimble The Thief, a clever and stealthy Raccoon burglar or pickpocket who is on the run from the law; Keilee The Tinker, a Beaver and technically savvy maker of equipment and machines; and Xander The Vagrant, a wandering rabble-rouser and trickster Opossum who survives on his words. Most of these Vagabonds have links to the given Clearing in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart and all are complete with Natures and Drives, stats, backgrounds, Moves, Feats, and equipment. All a player has to do is decide on a couple of connections and each Playbook is ready to play.

As its title suggests, the given Clearing in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is Pellenicky Glade. Its description comes with an overarching issue and conflicts within the Clearing, important NPCs, places to go, and more. The overarching issue is the independence of the Clearing. The Goshawk have managed to remain neutral in the Eyrie Dynasties civil war and in the face of the advance of Marquisate forces, but the future is uncertain. The Conflicts include the future leadership of the Denizens of Pellenicky Glade, made all the more uncertain by the murder of Alton Goshawk, the Mayor of Pellenicky Glade. There is advice on how these Conflicts might play out if the Vagabonds do not get involved and there are no set solutions to any of the situations. For example, there is no given culprit for the murder of Alton Goshawk, but several solutions are given. Pellenicky Glade is a scenario in the true meaning—a set-up and situation ready for the Vagabonds to enter into and explore, rather than a plot and set of encounters and the like. There is a lot of detail here and playing through the Pellenicky Glade Clearing should provide multiple sessions’ worth of play.

Physically, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is a fantastic looking booklet, done in full colour and printed on heavy paper stock. It is well written and the artwork, taken from or inspired by the Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, is bright and breezy, and really attractive. Even cute. Simply, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is physically the most impressive of all the releases for Free RPG Day 2020.

If there is an issue with Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart it is that it looks busy and it looks complex—something that often besets ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying games. Not only do players need their Vagabond’s Playbooks, but also reference sheets for all of the game’s Basic Moves and Weapon Moves—and that is a lot of information. However, it means that a player has all of the information he needs to play his Vagabond to hand, he does not need to refer to the rules for explanations of the rules or his Vagabond’s Moves. That also means that there is some preparation required to make sure that each player has the lists of Moves his Vagabond needs. Another issue is that the relative complexity and the density of the information in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart means that it is not a beginner’s game and the Game Master will need a bit of experience to run the Pellenicky Glade and its conflicts.

Ultimately, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart comes with everything necessary to play and keep the attention of a playing group for probably three or four sessions. Although it needs a careful read through and preparation by the Game Master, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is a very good introduction to the rules, the setting, and conflicts in Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game—and it looks damned good too.

Grindhouse Sci-Fi Horror

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is many things. It is a lost ship to encounter and salvage and survive—and even steal. It is a means to create the layout of any starship you care to encounter. It is a moon to visit, a hellhole of auto-cannibalism, desperation, and caprinaephilia. It is a list of nightmares. It is a planetcrawl on a dead world including a bunker crawl five levels deep. It is a weird-arse incursion from another place, which might not or not be hell. It is all of these things and then it is one thing—a mini campaign in which the Player Characters, or crew of a starship, find themselves trapped around the dead planet of the title. Desperate to survive, desperate to get out, how far will the crew go in dealing with the degenerate survivors around the dead planet? How far will they go in investigating the dead planet in order to get out?

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is many things. It is a lost ship to encounter and salvage and survive—and even steal. It is a means to create the layout of any starship you care to encounter. It is a moon to visit, a hellhole of auto-cannibalism, desperation, and caprinaephilia. It is a list of nightmares. It is a planetcrawl on a dead world including a bunker crawl five levels deep. It is a weird-arse incursion from another place, which might not or not be hell. It is all of these things and then it is one thing—a mini campaign in which the Player Characters, or crew of a starship, find themselves trapped around the dead planet of the title. Desperate to survive, desperate to get out, how far will the crew go in dealing with the degenerate survivors around the dead planet? How far will they go in investigating the dead planet in order to get out?Published by Tuesday Knight Games, Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is the first supplement for MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game, which does Science Fiction horror and action. The action of Blue-Collar Science Fiction such as Outland, the horror Science Fiction of Alien, and the action and horror Science Fiction of Aliens. It works as both a companion and a campaign for MOTHERSHIP, but also as a source of scenarios for the roleplaying game. This is because it is designed in modular fashion built onto a framework. This framework is simple. The starship crewed by the Player Characters suffers a malfunction and is sucked into a star system at the heart of which is not a sun, but a dead planet upon which stands a Dead Gateway which spews dark, brooding energy from somewhere else into our universe. The crew is unlikely to discover this until later in the campaign, by which time they will have encountered innumerable other horrors and nightmares. With their ship’s jump drive engines malfunctioning and the ship itself damaged, the crew find themselves floating through a ships’ graveyard of derelicts. Could parts be found on these ships? How did they get here—was it just like their own ship? And where are their crews? Close by is a likely ship for exploration and a boarding party.

Beyond the cloud of derelict ships is a moon and this moon is a community of survivors. How this community has survived is horrifying, it having to degenerated into barbarism, to a point of potential collapse. Indeed, the arrival of the Player Characters is likely to drive the factions within the community to act and send it to a tipping point and beyond. Not everyone in the community welcomes their arrival, and even those that do, do so for a variety of reasons. However, in order to interact with the community, the Player Characters are probably going to have to commit a fairly vile act—and do so willingly. This may well be a step too far for some players, though it should be made clear that this act is not sexual in nature and will be by the Player Characters against themselves individually rather than against others. Nevertheless, it does involve a major a major taboo, and whilst that taboo has been presented and explored innumerable times onscreen, it is another matter to be confronted with it in as a personal a fashion as Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game does.

Then at last, there is the Dead Planet itself. This is a mini-hex crawl atop a rocky plateau with multiple locations. Not just the source of the system’s issues, nightmares, and madness, but a swamp, a crashed ship, wrecked buildings, a giant quarry, and more. Most of these locations require relatively little exploration, only the deep bunker of the Red Tower does. Plumbing its depths may not seem the obvious course of action for some players and their characters, but it may contain one means of the Player Characters escaping the hold that the Dead Planet has over everyone. Certainly, the Warden—as the Game Master in Mothership is known—may want to lay the groundwork in terms of clues for the Player Characters to follow in working out how they are going to escape.

Taken all together, these parts constitute the mini-campaign that is Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. Separate these parts and the Warden has extra elements she can use in her own game. So, these include sets of tables for generating derelict ships and mapping them out, jump drive malfunctions, weapon and supply caches, colonists and survivors, luxuries and goods found in a vault, and nightmares. All of these can be used beyond the pages of Dead Planet, but so could the deck plans of the Alexis, an archaeological research vessel, the floor plans of the bunker, and so on. Not too often, and likely not necessarily if Dead Planet has been run.

Physically, Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is like MOTHERSHIP itself, a fantastic exercise in use of space and flavour of writing. However, the cost of this wealth of detail is that text is often crammed onto the pages and can be difficult to read in places. It also needs a slight edit. The maps are also good, though artwork is unlikely to be to everyone’s taste.

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is very good at what it does and it is exactly the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game needed—more of the near future setting, the monsters, and the horror that it hinted at. Dead Planet goes further in presenting a mini-campaign and elements that the Warden can use in her own game, although it is still not what MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game really needs and that is the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror RPG – Warden’s Horror Guide. As a horror scenario, the set-up in Dead Planet is both creepy and nasty, but definitely needs the input of the Warden to bring it out. There is no real advice in Dead Planet for the Warden, and both it and its horror will benefit from being in the hands of an experienced Referee, if not an experienced Warden.

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is a nasty first expansion for MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game, and that is exactly so delivers on the horror and the genre action first promised in the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. Ultimately though, the horror in Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is not for the fainthearted, being a Grindhouse Sci-Fi combination of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Event Horizon.

[Free RPG Day 2020] LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 [https://www.fanboy3.co.uk/] in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 [https://www.fanboy3.co.uk/] in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is a little different. Published by 9th Level Games, Level 1 is an annual RPG anthology series of ‘Independent Roleplaying Games’ specifically released for Free RPG Day. LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is a collection of fifteen featuring role-playing games, standalone adventures, two-hundred-word Roleplaying Games, One Page Dungeons, and more! Where the other offerings for Free RPG Day 2020—or any other Free RPG Day—provide one-shot, one use quick-starts or adventures, LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is something that can be dipped into multiple times, in some cases its contents can played once, twice, or more—even in the space of a single evening! The subject matters for these entries ranges from the adult to the weird and back again, but what they have in common is that they are non-commercial in nature and they often tell stories in non-commercial fashion compared to the other offerings for Free RPG Day 2020. The other differences are that Level 1 includes notes on audience—from Kid Friendly to Mature Adults, and tone—from Action and Cozy to Serious and Strange. Many of the games ask questions of the players and possess an internalised nature—more ‘How do I feel?’ than ‘I stride forth and do *this*’, and for some players, this may be uncomfortable or simply too different from traditional roleplaying games. So the anthology includes ‘Be Safe, Have fun’, a set of tools and terms for ensuring that everyone can play within their comfort zone. It is a good essay and useful not just for the fifteen or so games in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020.

The difference in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is that it carries advertising. This advertising is from its sponsors, but it gives Level 1 an old-style magazine feel.

Level 1 opens with the odd. Kira Magrann’s ‘Moose Trip: a game about moose who eat psychedelic mushrooms’. It turns out that as part of their idyllic life in the human-occupied wilds of Montana, Moose actually eat psychedelic mushrooms to get high. Which is what they do in this game and then they engage in relaxed conversation about how they feel and their emotions. It includes twenty different ‘Mushroom Feelings’ and offers a short but relaxed, reflective game.

Density Media’s ‘A Clan of Two: A two-person storytelling game’ is inspired by Shogun Assassin or Lone Wolf and Cub. Whether as an assassin and his son on the run from the Shogun or a bounty hunter protecting his bounty rather than taking him in—see Midnight Run, one player takes the role of the protagonist, a warrior without peer who will adhere to a code. This might the code of Bushido, code of chivalry, and so on, but he will have broken part of the code and gone on the run. The other player takes the role of both Game Master and seer, that is, the baby of the baby cart assassin or the bounty hunter’s quarry, as well of the world around them. He will both roleplay this character and the world. ‘A Clan of two’ uses a table of descriptors and prompts derived from the I Ching to push the story along and to see how the world reacts to the protagonist’s actions. This gives a nice balance between player agency and setting, the player able to roleplay free of rolling dice, whilst the Game Master can focus on the setting and interpreting the results, but together telling a story.

Designed for one player and no Game Master, ‘Dice Friends’ by Tim Hutchings is a one-page game in which stories are built around dice to represent characters and their lives and adventures. Mechanically very simple, there is no genre or setting to this game and beyond some dice dying and some dice leaving, there is little in the way of prompts in the game. Its brevity means that the players need to have strong buy-in to the game and will need to work hard create the world in which the dice/characters live and leave or live and die. The lack of a hook and the need to build the whole world means that despite it being easy to pick up and play, ‘Dice Friends’ may well be too daunting for some.

‘After Ragnarök’ by Cameron Parkinson and Tyler Omichinski, is a post-life, post-apocalyptic roleplaying game of Viking adventure and legends! The player take the role of the Einherjar, the great heroes destined to feast and drink in Vahalla until Ragnarök. That day has come and gone, and with the Gods dead, the Einherjar remain, but with Valhalla decaying, they decide to set out and adventure for the great drinking halls which are still said to exist. This is a roleplaying game in which the Player Characters start out as great heroes with Legends that they create, but as they face Jotun, the great hounds of Hel, and worse, they will fall in battle. However, when they die, there is a chance that their ‘Legends’ will ‘Fade’ and so lose their legendary capabilities. This is much more of traditional roleplaying game, a heroic game of fighting against the dying of the light—that is, the dying of the Player Characters’ light.

Oat & Noodle’s ‘Sojurn’ is a second one-page game for one player and no Game Master. This idea is that the players are leaving on a journey and take three objects with them, such as a mask, an imp, and a key, and when they return from the journey, something has changed. This is another one-player game in which the player is prompted to tell a story, but with actual prompts and an implicit genre, is much less daunting than the earlier ‘Dice Friends’. ‘Breaking Spirals: A single-player RPG inspired by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance & Commitment Therapy’ by Cameron and Colin Kyle is also for one player and no Game Master, but is more complex in that it presents a reflective, self-help game as a tool for active meditation and perspective. To be honest, it is more exercise than game, for although steps can be taken and there can be a sense of achievement in going through the process, there is no sense of winning in traditional way or of a story told. Not that there necessarily has to be either, but the lack either makes it an exercise rather than something to be played.

‘Bird Trek: A game about raptors in space’ by Maarten Gilberts & Steffie de Vaan is a co-operative game of sentient raptor birds in space who as a flock to steal things, but must make its annual migration from Caldera to Frigia via several moons. Many of these moons are strange and growing stranger every year, making the migration more difficult and increasing the likelihood of the flock’s hunger and exhaustion grow. This is a storytelling game about survival and loss as well as exploration and just as well could have been set between Africa and Europe as it could outer space.

In Graham Gentz’s ‘In the Tank: Roleplaying the life of an Algae Colony in a Tank’, the players take on the role of aspects of algae living in a tank. Individually they control aspects such as width, cell, green, and so on, but together they control it collectively. Their aim is achieve sentience and to avoid death, but from Moment to Moment, they must respond to complications, problems and stimulations from inside the tank and outside the tank—the latter often at the hand of ‘The Dave’. Exactly what ‘The Dave’ is, is up for speculation—tank owner, laboratory technician?—but the Dave Master creates the Complication and the Algae responds to it. Successfully overcome a Complication and the Algae moves closer to sentience, the player with the successful means of overcoming the Complication becoming the new ‘Dave Master’. As a game, ‘In the Tank’ is likely to escalate into sentience and success, or spiral into death and disaster, the point being that either result is acceptable, and it is the story told along the way that matters.

‘Love is Stored in the Elbow’ by Corinne Taylor is a single-character, multi-player in they explore the relationship between emotions, memory, and physical touch. It includes solid guidelines as which parts of the body and what emotions the players do not want to include in their game, and after randomly assigning the agreed upon emotions to the accepted parts of the body, take it in turns to narrate a memory involving an emotion and its connected body part. This can build on, but not negate previous memories, but once done, the players will have created a lifetime’s worth of memory. Potentially silly, potentially adult in nature, this is a nicely done story told through a life.

Midsummer Meinberg’s ‘Graveyard Shift’ is a three-player game about the alienation of working late at night for minimum wage. It explores poverty, family obligation, dead-end jobs, loneliness and alienation, and also drug use as self-medication—so it involves obviously adult themes. The players take the role of the worker, his family, and three customers on a single night and face the drudgery and complication that this brings. There is some excellent roleplaying potential in this situation as the Worker is ground down by his situation and the humiliation he suffers in dealing with difficult customers and the demands of his family all the whilst want to quit.

The fourth one-page game is ‘At Least We Have Tonight’ by Matthew Orr and it again suffers from needing a strong buy-in by the players. Up to eight of them roleplaying slaves aboard a Roman trireme, who at the end of the day recount its events—the moments which broke the toil, such as the song we sang or an injury suffered, what their life was before ship and what ambitions they harbour for life after—if any. It is all quite dispiriting and will either fall flat because of the lack of engagement or descend into melancholy if the players do develop something from the prompts given.

‘Bad Decisions’ by Scott Slater, Michael Faulk, and Jeff Mitchell is a horror game about those moments when a character does something foolish—go into the basement alone, pick up hitchhikers, read the wrong book, et cetera. It is played in two phases. In the first phase, the players take it in turns to narrate the story, pushing the characters into situations where bad decisions can be made, and then rolling to see if they narrate the terrible outcome. In phase one, the results are mild injuries only, but in phase, the story escalates and the players bluff against each other to see which of them survives. The outcomes of the bad decisions in this phase are always fatal as the monster is revealed and chases the characters through the woods. Death is also sudden, nasty, and foolish. Slightly fiddley in its use of the dice, ‘Bad Decisions’ has a wealth of genre conventions to draw from.

Ty Oden’s ‘Hellevator’ is design for a large group whose characters are stuck in a cursed elevator with a devil. The devil seeks to kill or convert everyone in the elevator, whilst the humans must identify and eliminate the devil in order to avoid being corrupted or killed—and so escape. Fortunately, the devil can only use his infernal powers in the darkness. Essentially, this is a LARP, a variant of Murder in the Dark or Mafia or The Resistance played in a six-foot by six-foot space, the Devil player eliminating players in the darkness with a firm touch on the shoulder, the survivors denouncing the devil—or human, if wrong—in the light. The game is obvious into its inspiration, but more interesting in its optional devils which add variants. Another issue of course is that the players have to be happy with playing in the confined space, if only simulated.

‘Mesopotamians: A little game about undead warrior kings making it big as a rock and roll band’ by Nick Wedig is a bonkers set-up, but undead ancient kings on a tour is not an unenticing one. As their tour progresses, it must deal with concerns like money and fame, but at every town face other issues such as why the townsfolk dislike them, what criminal plot do they accidentally get involved in, or what they are squabbling about in UTTRATU, the Econoline Van that is their tour vehicle? The aim here is to increase value of the Concerns and so win, and this is done by rolling dice at Crisis Points, aiming to find a dice with results of eight or more. As much as this is a great concept, the rules are not very explained and it could have done with an example of how to handle a Crisis point.

The last game in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is ‘Savage Sisters: Heroic Women Against a Barbaric World’ by Adriel Lee Wilson with Chris O’Neill. Inspired by Xena Warrior Princess, the Player Characters in ‘Savage Sisters’ forma Sodal, a group of powerful, female warriors. Together the player define the rules of the Sodal and each define their Savage Sister. During play, the players take turns as the GM—the Grandmother—to relate tale as they sit around the fire on eve of a great event, such as a battle or a birth or a wedding. When faced with a difficult challenge, a Savage Sister’s player rolls her die to match one of the numbers listed for the test—which can be a books, boots, blades, or bones test. If the Savage Sister succeeds, then she maintains control of the narrative, otherwise the Grandmother takes control. Ultimately, the Soldal is doing two things. One is facing tests to try to improve its destiny—represented by a pool of tokens. If there are three or more tokens in the pool, all test rolls are made at advantage, otherwise the Sodal is suffering despair and Savage Sisters roll at disadvantage. The other is to tell tales whose subject matters and details are determined before the game starts by answering a few questions and then randomly assigned to the players. It could have been better organised and the set-up clearer, but ‘Savage Sisters: Heroic Women Against a Barbaric World’ is probably the most open ended of the games in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 and is worth revisiting again.

LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is a slim, digest-sized book. Although it needs an edit in places, the book is well presented, and reasonably illustrated. In general, it is an easy read, and everything is easy to grasp.

LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is the richest and deepest of the releases for Free RPG Day 2020. There is something for everyone here, from postapocalyptic warriors to midnight shift workers, and any one of the games in the anthology will provide a good session’s worth of play. Not all of the games are of the same quality though with perhaps the best and the most interesting being ‘A Clan of Two: A two-person storytelling game’, ‘After Ragnarök’, and ‘Graveyard Shift’ with ‘Mesopotamians: A little game about undead warrior kings making it big as a rock and roll band’ being something that needs a bit more development. Despite the variable quality of its content, of all the releases for Free RPG Day 2020, LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is the title that playing groups will come back to again and again to try something new each time.

Have a Safe Weekend

Feculent Fantasy

The primary drive behind the Old School Renaissance is not just a nostalgic drive to emulate the fantasy roleplaying game and style of your youth, but there is another drive—that of simplicity. That is, to play a stripped back set of rules which avoid the complexities and sensibilities of the contemporary hobby. Thus, there are any number of roleplaying games which do this, of which Ancient Odysseys: Treasure Awaits! An Introductory Roleplaying Game is an example. Ordure Fantasy, published by Gorgzu Games is an incredibly simple Old School Renaissance-style fantasy roleplaying game using a single six-sided die with a straightforward mechanic throughout, and providing four character Classes, offbeat monsters, and table upon table for generating elements of the world, from setting, quests, and locations to NPCs, dungeons, and random encounters.

The primary drive behind the Old School Renaissance is not just a nostalgic drive to emulate the fantasy roleplaying game and style of your youth, but there is another drive—that of simplicity. That is, to play a stripped back set of rules which avoid the complexities and sensibilities of the contemporary hobby. Thus, there are any number of roleplaying games which do this, of which Ancient Odysseys: Treasure Awaits! An Introductory Roleplaying Game is an example. Ordure Fantasy, published by Gorgzu Games is an incredibly simple Old School Renaissance-style fantasy roleplaying game using a single six-sided die with a straightforward mechanic throughout, and providing four character Classes, offbeat monsters, and table upon table for generating elements of the world, from setting, quests, and locations to NPCs, dungeons, and random encounters.Ordure Fantasy: A simple d6 roleplaying game starts with its mechanic. To undertake an action for his character, a player rolls a single six-sided die, aiming to get equal to or under the value of a Skill or Ability to succeed. Easy and Hard Tests are made with two six-sided dice, the lowest value kept for Easy Tests, the highest value retained for Hard Tests. For deadly, dangerous, cataclysmic or annoying situations, the Referee can demand that a player make an ‘Ordure Test’. On a result of a six, the ‘Ordure’ of the situation happens, on a result of four or five, the Player Character gets a rumbling, warning, or unsettling portent of the ‘Ordure’. If the ‘Ordure’ situation persists, the ‘Ordure’ range on the die expands from a six to five and six, then four, five, and six, and so on. Essentially, the ‘Ordure’ Test is a random response generator to dire situations, enforcing the fact that the world is a dangerous place, one in which the ‘heroes’ are not actually capable of dealing with based on their own abilities or skills—more random fortune. However, Ordure Fantasy does not suggest what such situations might be.

Combat is more complex in Ordure Fantasy. Initiative is handled by lowest rolls acting first, and attacks by a player rolling under his character’s Combat skill. If a Player Character is hit, then his player can roll a Body or Mind Test for his character to defend. All attacks inflict a single point of damage which is deducted from the Health of a Player Character or NPC. Enemies—whether a monster or an NPC, have only the Ability, that is, Health, and when Health, whether that of a Player Character, monster, or NPC, is reduced to zero, then they are dead. In addition, some Player Characters, NPCs, and monsters have abilities and skills that will inflict various effects in addition to the deduction of a single point of Health—and they can be quite nasty. Thus, the Nursing Acid Wing has a grasp attack and the Mercenary Class’ Sword Skill can be good enough to lop off the limbs and appendages of his enemies—if the rest of the Combat Test is good enough.

Ordure Fantasy provides a half-dozen monsters—not really enough, but very much not traditional fantasy in terms of their design, a page of notes and advice for the Referee, all decent enough, before it gets down to creating Player Characters. A Player Character is defined by three Abilities—Body, Mind, and Luck, plus his Health, Class, equipment, and money. There are four Classes—Mercenary, Conjurer, Scoundrel, and Curate, each of which maps onto the four Classes of classic fantasy roleplaying. The Mercenary is soldier of fortune, trained in the arts of war without loyalty to any lord or realm; the Conjurer an autodidact explorer of unreal realms and summoner of fey things; the Scoundrel a charming alley rat unconcerned with the law; and the Curate, the neophyte scion of some cult excommunicated for heretical and gnostic preachings. So, there is a sense that the characters of the world of Ordure Fantasy are ne’er-do-wells, brutes, uncaring, cynical bastards in a landscape of grim and dangerous peril.

Each Class has four Skills and a Boon. Skills can be used as often as necessary, whilst Boons can be used once per game session. For example, the Mercenary has Bow, which provides a ranged attack; Sword, a melee attack capable of taking off limbs; Shield, which improves a Mercenary’s defence for a melee turn; and Intimidate. The Mercenary’s Boon is ‘Execute’. Simply, the Mercenary declares a target and his next successful attack against them is instantly fatal. Ouch!

To create a Player Character in Ordure Fantasy, a player assigns a value of three to one Ability, two to another, and one to the third. All Player Characters have a Health of five. The player selects a Class and picks three of its Skills, and just like Abilities, assigns a value of three to one, two to another, and one to the third. It is a simple, fast process.

Evota the evasive

Scoundrel, Level 1

Body 1 Mind 2 Luck 3

Skills: Negotiate 1, Hide and Sneak 3, Lockpick 2

Boon: An Old Friend (Roll twice on each side of the Random Reaction table and select combination for the relationship).

Money: 30 sp.

Magic in Ordure Fantasy is both interesting and banal. The Curate simply gets Heal, Curse, and Resurrect as Skills, and these feel banal and flavourless. They ape the divine magical abilities found in other fantasy roleplaying games and they are simply not that interesting. In comparison, the Conjurer has interesting magic and really gets to do things with it. What a Conjurer can do is summon. This is modelled with the Summon Emotion, Summon Element, and Summon Being Skills. The first of these enables a Conjurer to flood a sentient being’s mind with an emotion of the Conjurer’s choice, the second to summon a fist-sized ball of an element the Conjurer has seen before, and the third a being the Conjurer has seen before—and the Conjurer can control numerous beings once he rises far enough in Levels. Simply, there is a flexibility to these Skills, a flexibility limited only by the player’s imagination and the Referee’s agreement. So there is potential for a lot of fun with the Conjurer Class, whereas the Curate not so much.

Experience again is simple in Ordure Fantasy. A Player Character who survives an interesting, dangerous, exciting, or entertaining session goes up a single Level. When he does, the Player Character is awarded a single point which his player can assign to an Ability or Skill to increase its value by one. The maximum value for any Ability or Skill is four, a Player Character can learn its fourth Skill at Third Level, and the maximum Level for any Player Character is six.

Equipment—especially enchanted and mythical equipment, is again simply handled. The former, for example, magical maps or a master thief’s tools, make Skill Tests easy, whilst the latter are so well crafted and infused with magic that they grant a +1 bonus to a particular Ability or Skill. Given the one to six scale of Ordure Fantasy, such mythical items are really powerful and may provide benefits beyond the simple bonus.

Over a third of Ordure Fantasy is devoted to ‘Referee’s Tables’. These start out with a table for what the Player Characters doing when the first session starts, and then goes on to define the danger in the particular realm, what adventurers are needed for or do, and what the town where the Player Characters are is, what quest is available there, what the dangerous region outside the town is, and so on. There are twelve tables here, each with multiple options, which with just a few rolls of a die, the Referee can generate a sheaf of hooks and elements around which she can base an encounter, a scenario, or even a mini-campaign, perhaps even as the game proceeds.

Physically, Ordure Fantasy is a nineteen page, 2.78 Mb, full colour PDF. The layout is clean and tidy, and it is illustrated with okay, if scratchy pen and ink drawings. The use of colour is minimal though and although attractive, does not add to the look of the game. It does need an edit in places. The last page in Ordure Fantasy is the character sheet, which clear and easy to use, and as a nice touch, includes the basics of rolling Tests and the Combat Rules for easy reference by the players.

If there is anything missing from Ordure Fantasy, it is a scenario. Certainly, the inclusion of such a sample adventure would have supported its ‘pick up and play’ quality, for Ordure Fantasy is really easy to learn and lends itself to quick and dirty games. Similarly, It would have been nice to have seen more monsters, though there is a table for generating foes, but it is kind of buried in the back of the game. The only other issue is the Curate Class, which is more useful to have someone playing it rather than actually being interesting to play.

Overall, Ordure Fantasy does what it sets out to do, and that is present a stripped down, fast-playing grim and gritty set of mechanics, that support its grim and gritty tone.

[Free RPG Day 2020] The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

The third offering from Renegade Game Studios is The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl, a quick-start for Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys. It presents a full scenario—with room for expansion and development by the Game Master, an explanation of the rules, and four pregenerated Player Characters, all designed to introduce both players and Game Master to the world of Overlight. This is a world of seven great continent, known as Shards, hanging in the sky under each other in a sky of limitless, unending light. These continents may shift horizontally, but never vertically, night only falling when one continent passes over another. Each continent is different, from the rocky towers and crumbling mesas across an expanse of blasted desert that is Nova, home to giant, sentient and meditative centipedes, called Novapendra, to Pyre, a landscape swathed in tundra and steppes, rarely lit beyond the fiery glow of its volcanos. They are home to numerous species, not just Humans or Haarkeen, but also Teryxians, the small, feathered reptilians of Quill, once emperors, but now renowned as academics and philosophers; the tribal, sometimes tree-like Banyan; and the eerily tall and thin, mask-wearing Aurumel of Veile, who aspire to build great things.

To a certain few, the brilliant, white light of the Overlight can split into a spectrum of different colours and Virtues—Compassion (green), Logic (blue), Might (red), Spirit (white), Vigor (orange), Wisdom (purple), and Will (yellow). So with ‘Root!’, a Banyan can encourage the vines and branches in his body to grow and grasp something—a person, an object, the ground—in a particularly tight grip or with ‘Speaker’s Fire’, an Embertongue can influence others in a soothing subtle fashion. The Overlight flows through and around everything, but those who can manipulate it are known as Skyborn and their powers of the Overlight as Chroma.

A character in Overlight and thus The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is defined by the seven Virtues—Compassion, Logic, Might, Spirit, Vigor, Wisdom, and Will. Most Virtues have Virtue has two or skills attached to it and both skills and Virtues are rated by die type. The exception is Spirit, which is just a pool of points for activating Chroma. Besides a name, a character will also be defined by his Folk—species and culture, core Virtue, a background, and wealth. To undertake an action, a character’s player rolls a Test, which depending upon the circumstances can be a Skill Test, an Open test, a Wealth Test, or a Chroma Test. For any Test, the player rolls seven dice, usually consisting of three dice equal to the character’s skill, three equal to his Virtue, plus the Spirit die, which is always four-sided die. For example, a Banyari faced by an angry animal which he wants to calm down, his player would roll three ten-sided ice for his Compassion Virtue, three six-sided dice for his Beastways skill, plus the Spirit die. Results of six or more count as a success and at least two successes are required to succeed at a Test, though without any flourish. A roll of four—or Spirit Flare—on the Spirit die can add a further success. The type of dice rolled varies depending upon the type of Test, but all are built around a pool of seven dice. For example, Chroma Tests, used to active Chroma abilities, typically use a combination of two Virtues plus the Spirit die—and it is the result on the Spirit die which determines how many Spirit points activating the Chroma costs. If it is too many and the character is low on Spirit points, the character suffers a Shatter as the raw divinity of the Overlight powers through him. This can lead to strange side effects and once a character has suffered his third Shatter for a Chroma, he is burnt out and cannot use that Chroma again. Overall, the rules in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl are succinctly described in just seven pages, including the skills list.

Four pre-generated characters are provided to play the scenario in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl. They include a Banyari Rootlord capable of using the Overlight to photosynthesise healing, grasp others with its vines and branches, or lash out in a fury of red fists and spectral fire; a Pyroi Embertongue capable of making friends and influencing others, and creating fire; a Haarken Grifter capable of hearing conversations at a distance; and a Teryxian Tutor capable of issuing uncompromising commands. Every character comes with three or pages of backgrounds and stats.

The scenario in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is the eponymous ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’. This is a four-act mystery and missing persons adventure, which offers a mix of horror and exploration as well combat and interaction. It takes place on the on the forested Shard of Banyan where the Player Characters come across The Aquila, a ship-beast known as a Chrysoara, stricken with a sickness, its crew dead from acts of self-inflicted violence. This may simply at random, or they may be going to the rescue of the crashed ship-beast, or they may look for a missing scholar, Zubidiah Molok, who may or not be known to one of the Player Characters, and who even be mentor to one of them. From clues aboard The Aquila, the Player Characters will learn that scholar has made a great discovery deep in the forest. Following these clues will lead the Player Characters into dangerous territory and reveal some of the secrets of Overlight’s past.

As a scenario, ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’ is okay. It presents some of the setting to Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys and it provides a good mix of action and investigation, interaction and exploration, combat and horror. Each of the four Player Characters should certainly have a chance to shine. However, because the setting for Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys, and thus, ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’, is different, this scenario is not going to be one that flows. There will be plenty of stops and starts along the way as the Game Master has to explain—if not the rules, for they are quite straightforward, then aspect of the setting after setting. As a quick-start, The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl needs a cheat-sheet for it background more than it does for its mechanics. That said, from the information contained in its pages, the Game Master should be able to create one, just as she will be able to create the maps that would have been useful to frame and reference ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’. Of course, if she is doing that, then a handout or two would make the scenario a whole lot easier for both Game Master and her players.

Physically, The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is well presented. It is decently written, full colour, and comes with nice artwork. The lack of maps is an issue, but more of a problem is the fact that what is probably meant to be read aloud purple prose is not clearly marked as such and it feels like the author is repeating himself with every location description. This is frustrating experience for the Game Master trying to use the descriptions—both in the purple prose and the write-ups intended for her, because they look the same.

If a Game Master is already running an Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys campaign, then The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatll is likely easy enough to add to a campaign and it provides a decent enough scenario. For a group new to Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys, then The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is a decent introduction or a one-shot, although it needs a bit more work and a bit more of an explanation than it really should.

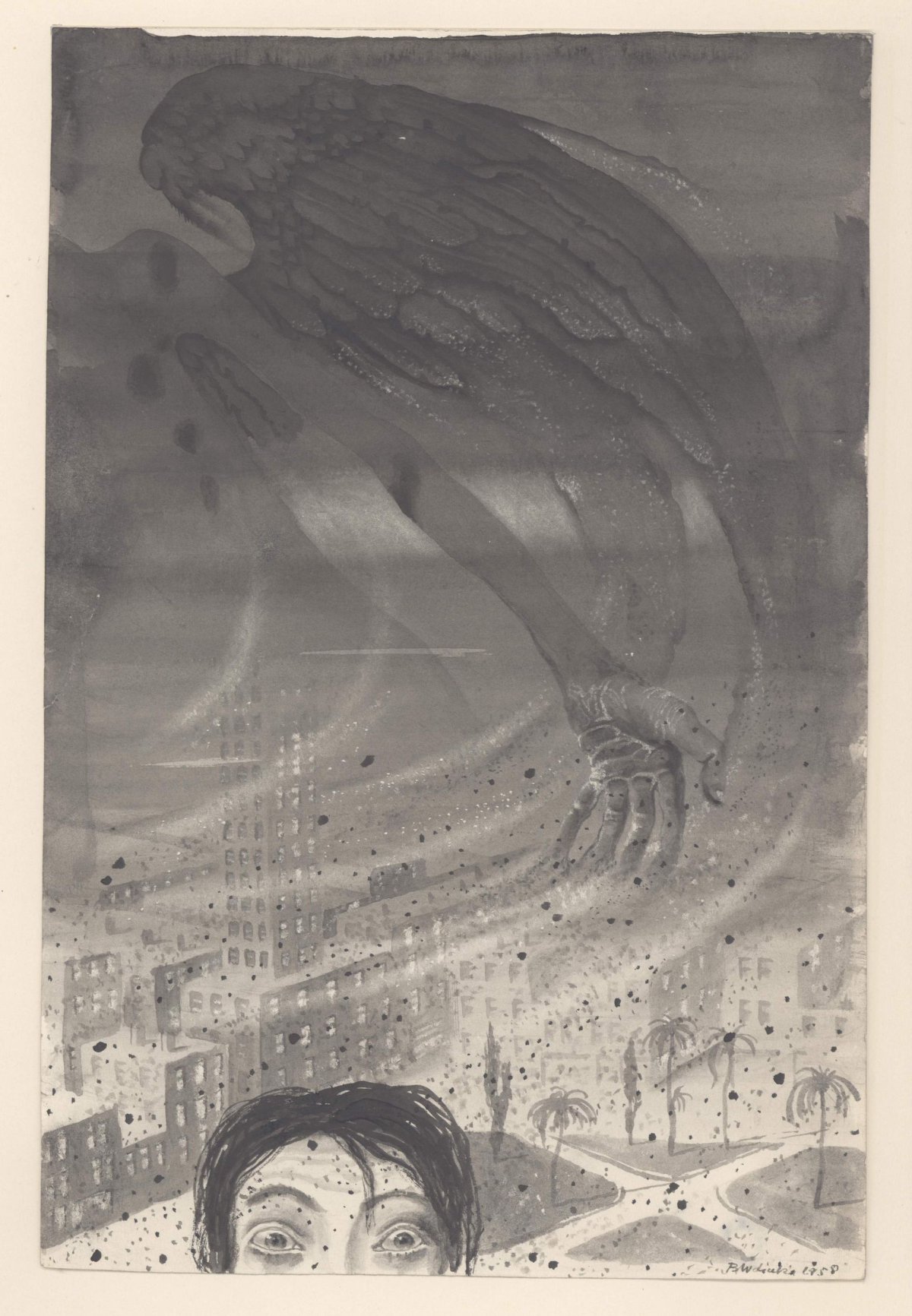

Richard Taylor (1902 - 70) - The Document

"Although Taylor is most known for his gag cartoons which poked fun at society, and humorous illustrations for a variety of books (Fractured French, My Husband Keeps Telling Me To Go To Hell, Half a Dollar Is Better Than None etc), it seems his private passion–and one he would pursue til late in life without seeking commercial benefit–was fantasy art. Taylor created a fantasy world called Frodokom, in which he based an entire series of watercolor, print and oil paintings that featured surrealistic creatures and landscapes. Maurice Horn’s Encyclopedia of Cartooning says of Taylor’s work “There is an individuality to his large-eyed, heavy lidded characters that makes one think of fairy tales and other worlds…” In the mid 1930s, he created 40 illustrations for Worm’s End, an adult fantasy book by Lionel Reed." - quote source.

Artwork found at Heritage Auctions.

A selection of Arkham House book covers by Taylor were previously shared here.

State of the Gallery: September 2020

Sunday Morning Porch Sale: September 20, 2020. Life’s No Fun Without A Good Scare.

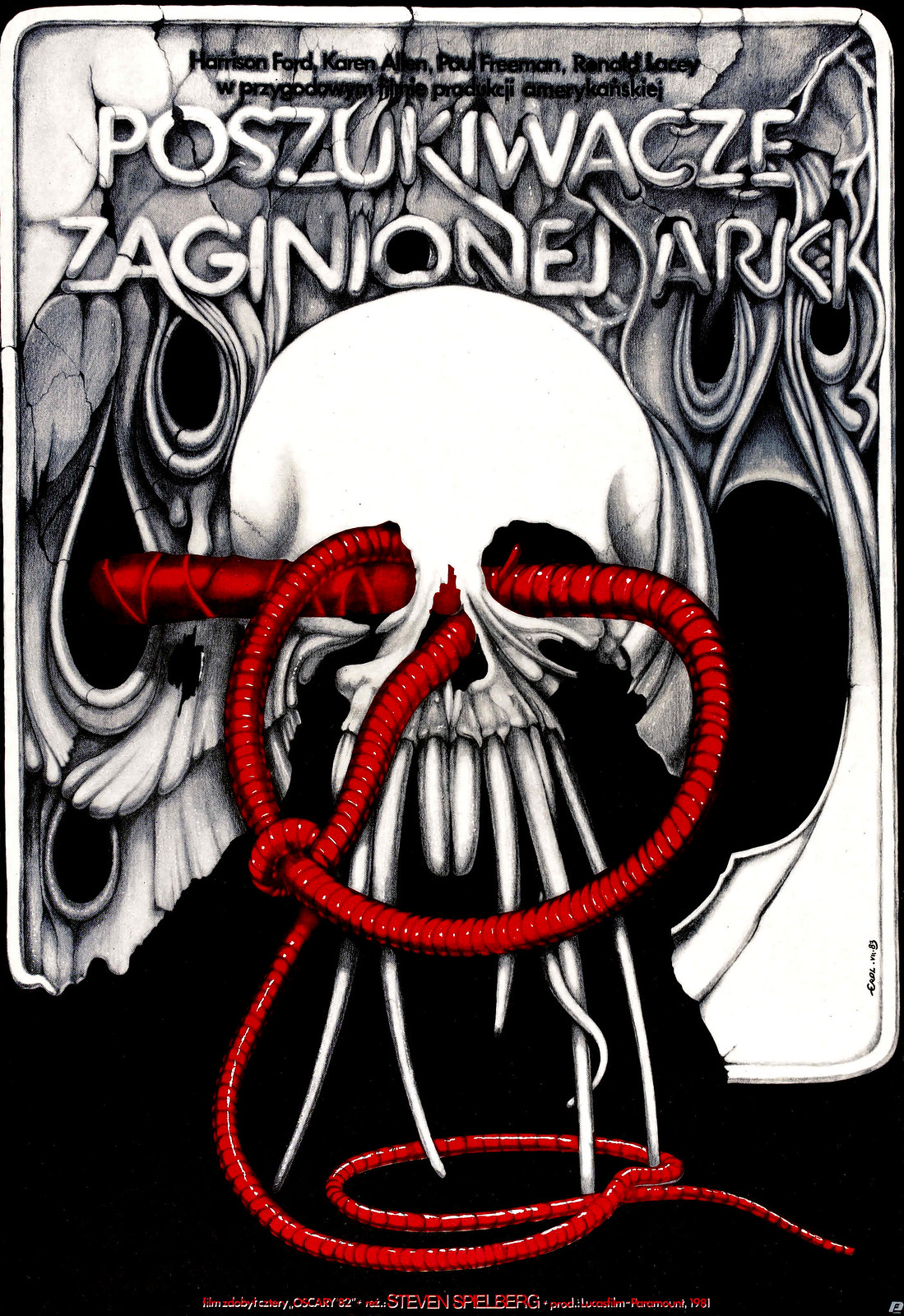

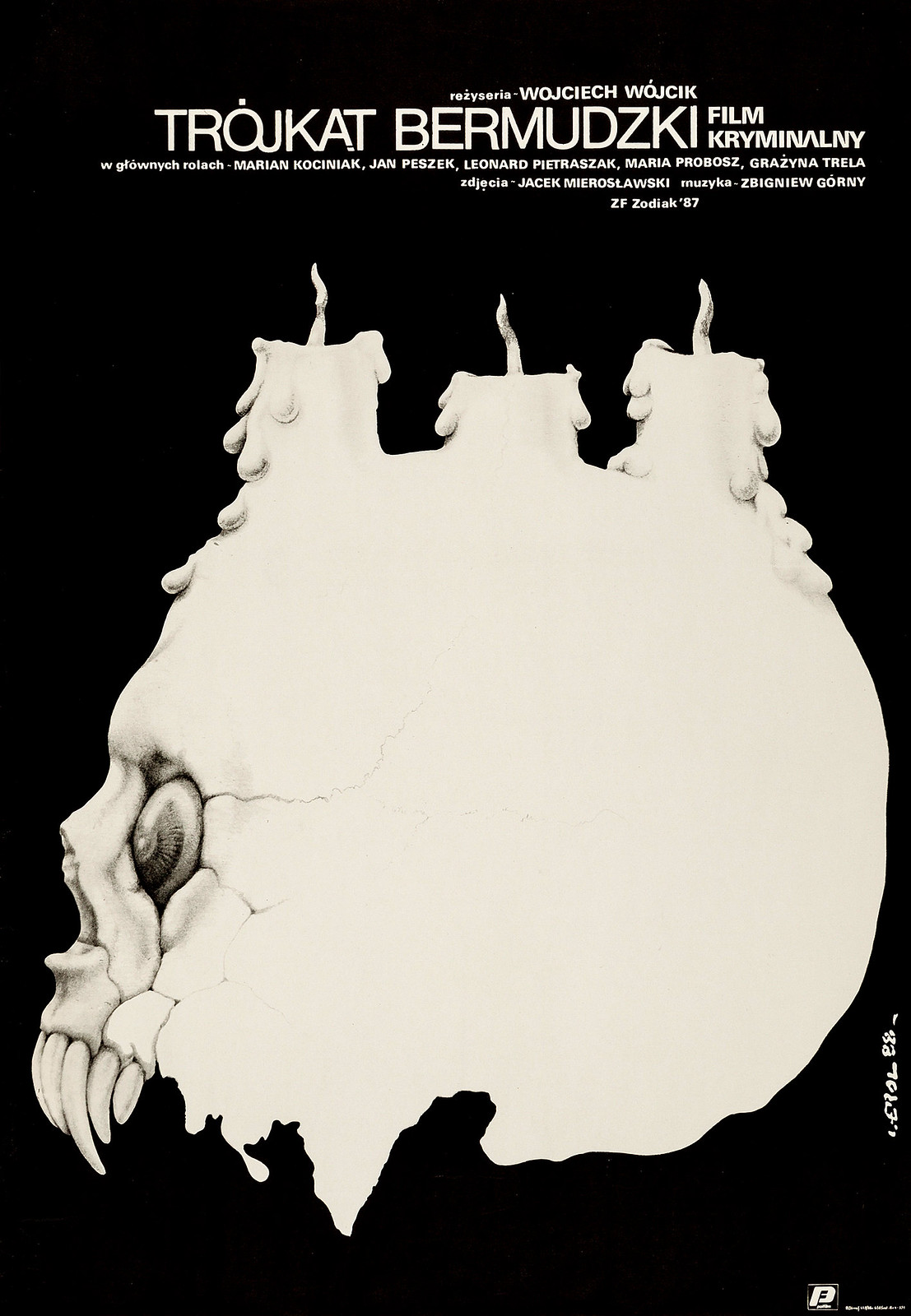

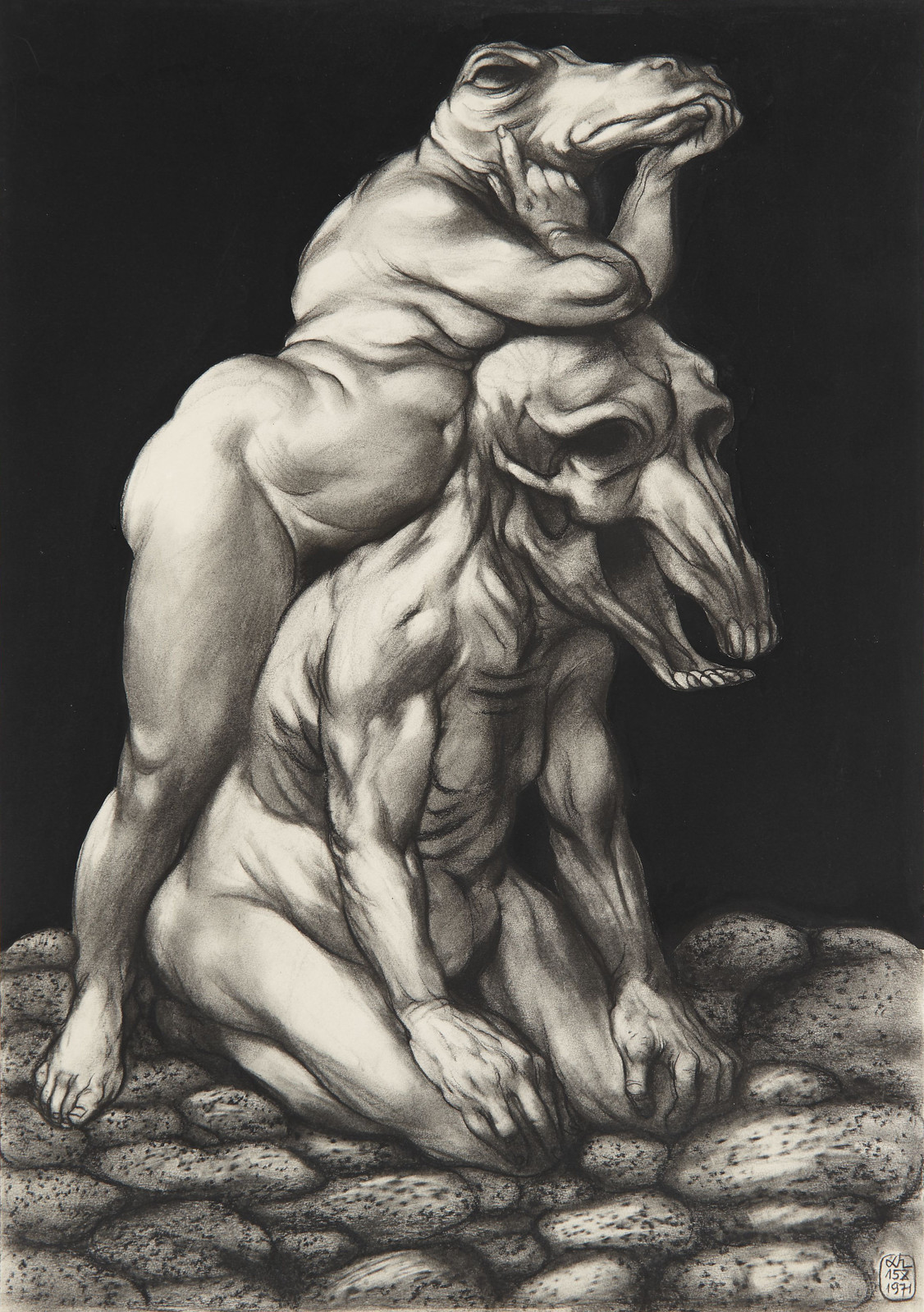

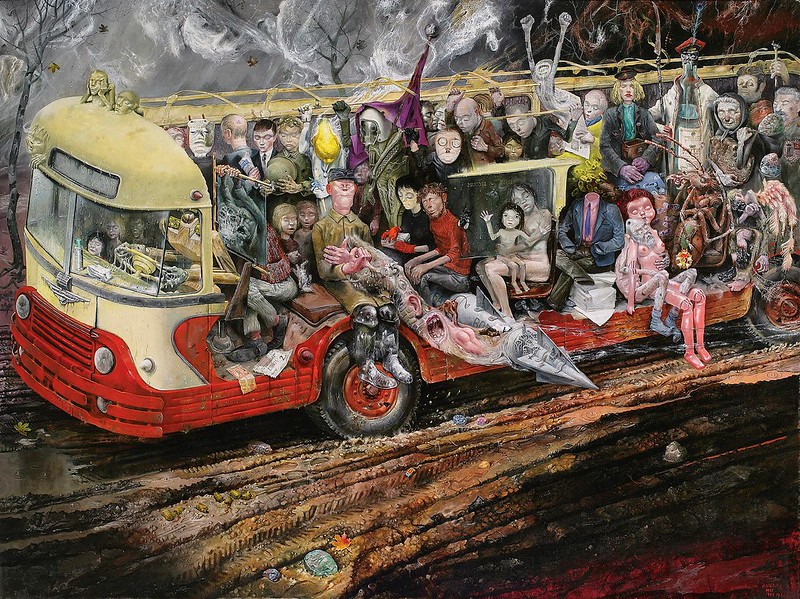

Jakub Erol (1941 - 2018) Polish Film Posters

Excited, Thrilled, Golly-Gee-Whizzed, and Titterpated too!

Been a while since I made a good Battletech post. I just finished Mr. Pardoe's recent novella "Divided We Fall". It's a great BT yarn, exciting, fast moving, engaging, and a real page turner. Also it has a special charm for me, as, in it, I am one of the fans Mr. Pardoe honors with an official alter ego in the Battletech Universe.

I've loved the game since it was first shown to me in 1987... Ah, High School, a terrible time in many respects, but my first friends were made over games of Battletech, and the universe has had my, sometimes near obsessive, attention ever since. Lord knows how much mayhem my imaginary other world self has caused, though I take pride in knowing I've always done all I could to minimize casualties, avoid the Civvies, and uphold the Aries Conventions...

I couldn't be more jazzed that a Character with my name is now a Cannonical part of the Universe; Brianne Elizabeth Lyons (Battletech Me) is a Colonel in Wolf's Dragoons! the best of the best! assigned to Logistics, which is exciting to me because I love thinking about Battletech logistics and strategic problems, and always imagined myself in that universe doing Operational Planning more than tactical field work. And, to boot, the Character pilots one of my favorite of all Battlemechs; the Urbanmech. I couldn't have asked for a more delightful and perfect representation, and it was all unasked, making it all the sweeter! Thank you Mr. P! You made one of my dreams a reality!

Anyhow, in the real world I've never quite felt comfortable with other super fans of the franchise, being a transwoman kinda has it's complications, even if they are usually inner ones, and I've shunned the community for the most part. It certainly doesn't help that the one tournament I entered; Amigocon '89, was ruined for me when I had to abandon the game because my Dad showed up and made me leave as we entered the final heat. I am sure I would have placed, but the cost to my familial relationships would have been severe... You know when you are really "in the zone" on something? you can see a few moves ahead, you know exactly what to do, and how to do it, and you can feel the victory in your fist? yeah, it's a rare exhilaration, I've felt it a few times, some hard fought chess games, and a couple of really busy Battletech games... And that day I totally had it. my Lance of Mediums; my Griffin, my pals playing an Assassin, a Centurion, and a Hunchback, we'd bested Warhammers, Riflemen, Marauders, and were still in good shape, fighting on a neat underground terrain board, using first rate tactics; scooting and shooting with care... it was a good free for all, and I would give my eyeteeth to see how it would have ended if I'd been allowed to stay and finish. it's my third greatest regret in my life. Well, that's all ancient history and water under the bridge as they say.

Times have changed since the late 80s... in the real world and in the game world. The Dragoons have a new logo...classic mech designs are re-imagined, and the clans have come, changing everything, everything except the one eternal truth; there will always be war so long as humanity remains...human.

Plans for October 2020

Adam Hoffmann (1918 - 2001)

Miskatonic Monday #52: Down New England Town

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

—oOo—

Name: Down New England Town

Name: Down New England TownPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Author: Michael LaBossiere

Setting: Small town, modern New England

Product: Scenario

What You Get: Ten page, 3.15 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: Hometown Horror Maestro Horror

Plot Hook: Sheriff stumped by removed remains of the recently deceased director of horror movies. Could his death have become a horror movie?

Plot Support: Five NPCs, new Mythos creature variant, and a map.Production Values: Tidy layout and decent illustrations.

Pros

# Potential hometown sidequest

# Simple story, one session scenario

# Good mix of NPCs for the Keeper to roleplay

# Potential convention scenario

# Easy to adapt to other time periods

# Roleplaying focused investigation

# Scope to play up the horror movie aspects

Cons

# Simple story, one session scenario

# Uninspiring new Mythos monster variant

# Underwritten investigation# one note, combat climax

Conclusion

# Solid addition to any ghoul campaign

# Scope to play up the horror movie aspects

# Roleplaying investigation needs development

Tour de Tabletop

A minor side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has delayed this review, because it has also delayed the reason for this review. The 2020 Tour de France was due to have started on June 27th and finish three weeks later on July 19th, but its starting date was delayed until 29th August and it is due to finish today, 20th September. Consequently, this review—of a cycling-themed game—is equally as late. Published by Lautapelit.fi, Flamme Rouge is a cycling racing game designed for two to four players, aged eight and above, which can be played in between thirty and forty-five minutes. The mechanics involve racing on a modular board, the hand management of dual decks, and simultaneous action selection, supporting play that is both simple and tactical, and ultimately, providing a game that really feels like a stage of one the Grand Tours—the Giro d'Italia, Tour de France, and Vuelta a España. Plus, there is nothing to stop a playing group to play Flamme Rouge more than once to simulate a Grand Tour!

A minor side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has delayed this review, because it has also delayed the reason for this review. The 2020 Tour de France was due to have started on June 27th and finish three weeks later on July 19th, but its starting date was delayed until 29th August and it is due to finish today, 20th September. Consequently, this review—of a cycling-themed game—is equally as late. Published by Lautapelit.fi, Flamme Rouge is a cycling racing game designed for two to four players, aged eight and above, which can be played in between thirty and forty-five minutes. The mechanics involve racing on a modular board, the hand management of dual decks, and simultaneous action selection, supporting play that is both simple and tactical, and ultimately, providing a game that really feels like a stage of one the Grand Tours—the Giro d'Italia, Tour de France, and Vuelta a España. Plus, there is nothing to stop a playing group to play Flamme Rouge more than once to simulate a Grand Tour!In Flamme Rouge, each player controls a team of two riders. One is the Rouleur, a good all-rounder, capable of maintaining a good pace throughout a race, the other is the Sprinteur, capable of bursts of great—typically as they are racing for the finishing line. Throughout the game, each player will control the speed of both his Rouleur and his Sprinteur, each of whom has a sperate movement deck. In general, he will keep his cyclists in the pack—or peloton—to conserve energy and speed, protecting the Sprinteur until close to the end when he can launch a sprint attack or he might launch a breakaway from the peloton and get to the finishing line before anyone else. However, this will exhaust a cyclist and probably enable the peleton to catch up. All cyclists though can take advantage of the slipstream effect to catch up and keep up with the cyclists in front of them. Since every team is trying to do this, the cyclists will be jockeying for position throughout the game.