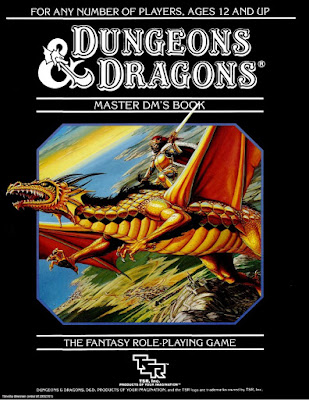

Dungeons & Dragons

Dungeons & Dragons has a problem. From

Dungeons & Dragons to

Basic Dungeons & Dragons and

Advanced Dungeon & Dragons, First Edition to

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, that problem has been one of Race. In

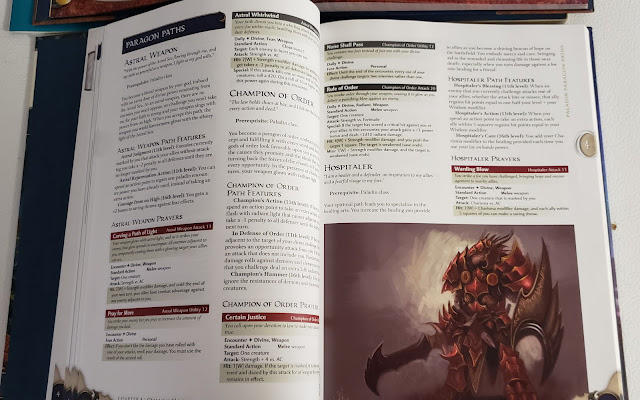

Dungeons & Dragons, a player’s choice of Race has always what core special abilities his character has, what attribute bonuses, what training he has undertaken, through a common Alignment for that Race, what his outlook upon the world is, as well as in many cases, what the world’s outlook is of his Race is in general. So under the current version of the rules, a Dwarf will an increased Constitution of +2, a starting age of fifty, tend to be of Lawful Alignment, stand between four and five feet tall and weigh about one-hundred-and-fifty pounds, be of Medium Size and have a base walking speed of twenty-five feet, have Darkvision, Dwarven Resilience against poisons, Dwarven Combat Training with battleaxes, handaxes, light hammers, and warhammers, tool proficiency with either smith’s tools, brewer’s supplies, or mason’s tools, and Stonecunning, a proficiency bonus in things related to stone. This question is, is this a typical Dwarf? Are all Dwarves like this? If so, is this not a racial stereotype, and would a Dwarven scribe have proficiencies with different tools rather than either smith’s tools, brewer’s supplies, or mason’s tools? Might the Dwarf be trained in different skills depending upon where and among whom he grew up? What if he grew up in a Halfling village, would he be exactly the same as the rules say he should be?

Another problem with

Dungeons & Dragons and race is why are there only Half-Orcs and Half-Elves? And why only with Humans? And why such characters with mixed parentage always seem to have difficulty with the Race of one of their parents—of not both? Then another problem with

Dungeons & Dragons and race is a continuation of the Race as stereotype issue. That problem can be addressed by answering the question, “What is the point of Orcs?”. Author

N.K. Jemisin’s answer is that, “Orcs are fruit of the poison vine that is human fear of “the Other”. In games like Dungeons & Dragons, orcs are a “fun” way to bring faceless savage dark hordes into a fantasy setting and then gleefully go genocidal on them.” By extension, this answer can be applied to the Drow too, but essentially the answer is that depicting Orcs, Half-Orcs, and Drow as evil and vile—and in the case of the first two, rapists and the victims of rape—is, well, racism.

Now if you disagree with those points or you do not think that such questions should be answered, or even asked, then this review is not for you. Nobody is going to come to your house and tell you that the way you play

Dungeons & Dragons is wrong. It might not be how the designers intended

Dungeons & Dragons to be played and it might not be what some parts of the

Dungeons & Dragons community want to hear about the game being played. If so, then again, this review is not for you, and the book being reviewed,

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e, is not for you. Similarly, that does not mean that there are no reviews on Reviews from R’lyeh of interest to you. For example, here is a review of

G2 Glacial Rift of the Frost Giant Jarl which was only published last week. However, if you are interested—whether with a sceptical or an open mind—in hearing about solutions to the problems that

Dungeons & Dragons has with race and racism, then this review is for you. And if you think that Wizards of the Coast, the publisher of

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, is

right to address the issue, then this review is also for you.

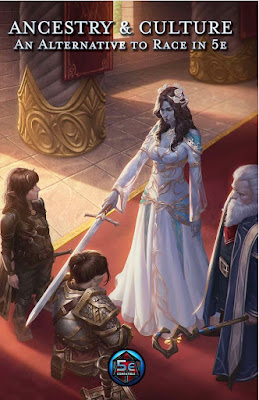

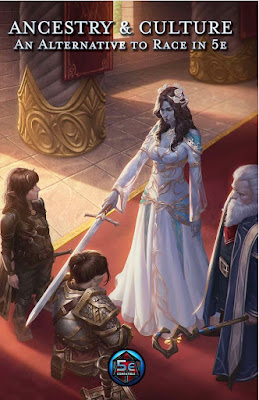

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e is published by

Arcanist Press. It is a supplement for

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition which offers solutions to both counter the problem of racism in the roleplaying game, options to enhance the diversity in the game, and a pair of scenarios which feature this diversity and have an emphasis on co-operation and roleplaying rather than on direct combat. The supplement begins by examining the problem, looking at where it originates from, and identifying how it exhibits in

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. At its heart, the roleplaying game takes a number of elements, mixes them together, and packages together under the term, Race. Fundamentally, it packages elements which are genetic—Age, Size, Speed, Darkvision, and so on, together with those which due to upbringing—Ability increase values, Alignment, Tool Proficiencies, and the like. The solution that

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e offers is to take each ‘Race’ as defined in

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition and divide its constituent parts into packages—or Traits—of their own. These Ancestral and Cultural Traits. So into the Ancestral Trait goes all of a species’ traits which would be inherited from their parents, that is, the simply biological elements such as Age, Size, Speed, Darkvision, and so on. This leaves learned or trained traits like Alignment, Languages, Proficiencies, Attribute bonuses, and so on, to go into the Cultural Trait. Thus, the Dwarven Ancestral Traits consist of Age, Size, Speed, Darkvision, Dwarven Resilience, and Dwarven Toughness, whereas the Dwarven Cultural Traits are made up of the Ability Score Increases—Constitution by two and Wisdom by one, Alignment, Dwarven Combat Training with battleaxes, handaxes, light hammers, and warhammers, tool proficiency with either smith’s tools, brewer’s supplies, or mason’s tools, and Stonecunning, a proficiency bonus in things related to stone, and the Dwarven language.

Now one of the issues with repackaging is where the Attribute bonuses go and it does look odd for them to be under the Cultural Trait and so suggest that they due to upbringing rather than innate, biological nature. After all, this is how it has been for the past forty years. The explanation is simple. The designers have moved away from the problematic concept that intelligence or strength is higher or lower in certain ethnic groups, a concept which underpins various aspects of racism. That said, as a player or a Dungeon Master there is nothing to stop you playing a Dwarf who was brought up among the Dwarven culture and combining the Dwarven Ancestral Trait and the Dwarven Cultural Trait to create a Dwarf in

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. The division though, allows a couple of interesting options. Most obviously you could create a character with Diverse Cultural Traits, that is, a character of one species who was brought up in the culture of another, so a character with the Ancestral Trait of one species and the Cultural Trait of another. For example, a Halfling who was brought up amongst Dwarves or a Human who was bought up amongst the Elves—such as Aragon did in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The other is Mixed Ancestral Traits in which a character has one parent of one Ancestral Trait and one parent of another Ancestral Trait. So you could have a Tielfling-Elf or a Halfling-Dwarf or a Dragonborn-Human and

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e provides rules on how to do this.

In addition,

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e offers two appendices offering additional rules, options, and resources. These include further rejecting the essentialist nature of the Cultural Traits which still suggests that a member of any one culture will have the same traits, so someone who grew up amidst a Dwarven culture would always have high Constitution and Wisdom, a Lawful Alignment, Dwarven Combat Training, particular Tool Proficiencies, and Stonecunning. How then, would you do a Dwarven scribe or merchant or entertainer. Here

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e provides the means to create that by giving a player the choice in what Attributes to increase, Tool Proficiencies to select, and the like. The supplement actually gives the Ancestral Traits and Cultural Traits for the core species in the

Player’s Handbook—Dragonborn, Dwarf, Elf, Gnome, Halfling, Human, Orc, and Tielfling, so that a gaming group can just slot that in the character creation process with ease. Of any other species, a second appendix suggests how they can be adapted to the new format of the Ancestral Traits and Cultural Traits.

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e also includes two scenarios. Both are what the author calls ‘’An Ancestry and Culture Adventure’ and both are set in and around communities with diverse, mixed-heritage populations. Both are designed for a party of five Third Level characters, but advice is given to adjust as necessary for weaker or stronger parties. In ‘Light of Unity’, the player characters come across a village beset by a shadowy corruption emanating from a nearby forest where a team of archaeologists has recently gone. To get the best out of the scenario, the player characters need to interact with the villagers and learn more of what is going on before proceeding to the source of the mystery. The interactive and roleplaying elements of the scenario are its best feature because otherwise ‘Light of Unity’ still adheres to the well-worn ‘village in peril’ set-up. It does not mean that it is unplayable, but perhaps just familiar. The second scenario, however, ‘Helping Hands’ takes the set-up one step further. It has a village in peril, in fact ablaze, but not only has the player characters help with the fire and the ensuing panic, but has them deal with the consequences, going for help in neighbouring communities. What is so enjoyable about ‘Helping Hands’ is that the solutions to problems it poses to the player characters are do not rely upon combat, but investigation and interaction. This is not to say that there is no combat in the scenario, but the emphasis is not upon fighting.

Physically,

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e is well written and presented. The maps are clear, but the standout feature is the artwork—which is gorgeous. None of it is in colour, but the depictions of a Dwarf of Dwarf Ancestry and Elf Culture, of a character of Dwarven and Orcish Ancestry and Orcish Culture, and others are really quite lovely.

If

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e is missing anything, it is perhaps that it does not explore what mixed cultures look like. It does what a character of mixed culture and heritage will look like, easily slotting into the

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition character creation process to do so, but not what a society and a culture might look. Of course, the scope for that would be enormous, but some advice might have been useful.

Ultimately, if you have an issue with either the questions raised by

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e or the solutions its offers, then the book is entirely optional. Bear in mind though, that Wizards of the Coast will be addressing them as the publisher of

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition and so the roleplaying game will be changing. And again, nothing is stopping you from ignoring those changes and adhering to the version that you like. However, what

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e is doing—and what Wizards of the Coast is going to do—is looking at Dungeons & Dragons from another perspective and asking difficult, uncomfortable questions about the game, and not only identifying problems with the game, but offering solutions. And even if you still want to play a Halfling who is a Halfling with both the Halfling Ancestral Trait and Cultural Trait or a Tielfling with both the Tielfling Ancestral Trait and Cultural Trait, you still can, but other players sat round the table might not want to, and

Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e gives them options to mix and match the options that they want, to create the characters that they want. Plus, it is doing it without the stereotyping of the Race element in

Dungeons & Dragons. It means that you can create characters who can still be interesting without being stereotypes or clichés and without being, well, racist—even if unintentionally.

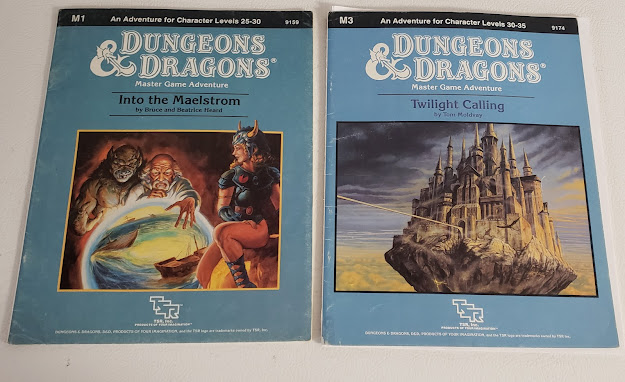

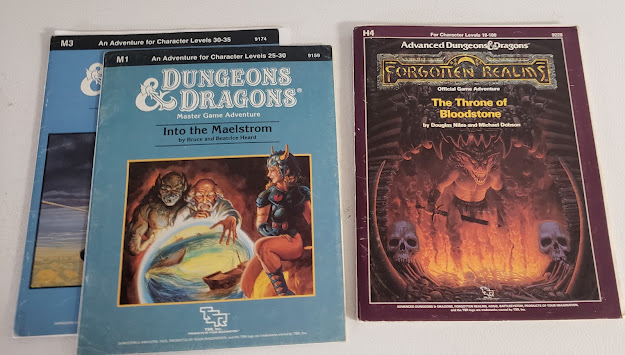

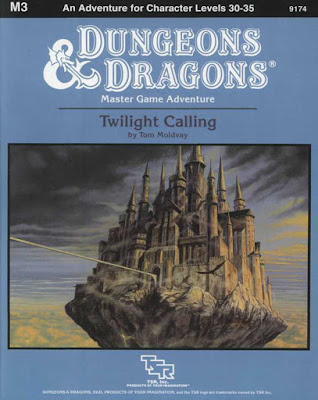

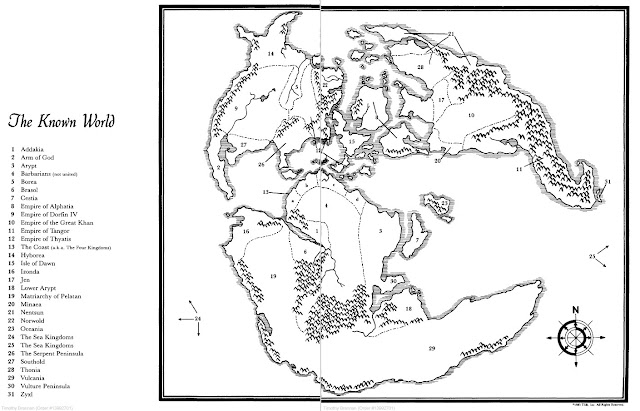

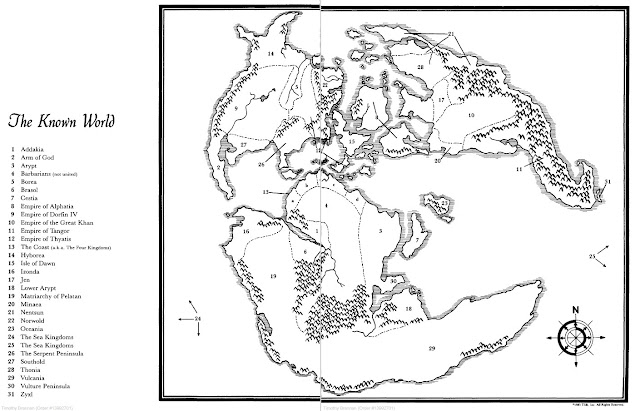

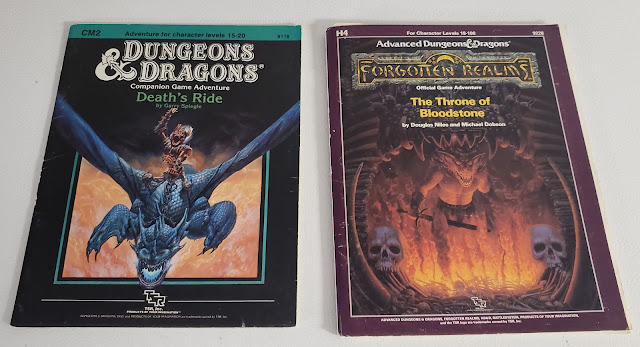

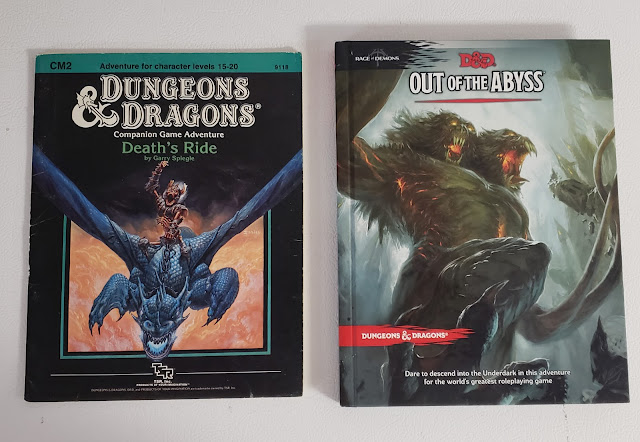

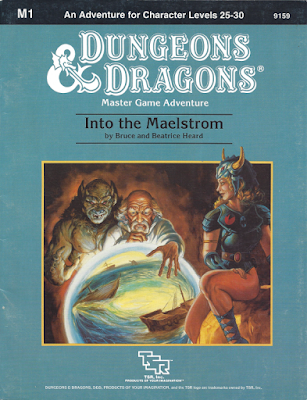

In some ways, I do wish I had read M1 before I had picked up M3. I had picked both modules up around 10-13 years ago while looking for a good epic level adventure for my kids then D&D 3.x game. They were into the epic levels of D&D 3, with the lowest level at 24 and the highest at 29. They were on this huge campaign against what they thought was the machinations of Tiamat. M1 was very good choice since I love the idea of flying ships (D&D should be FANTASTIC after all) but the base plot didn't work for the adventure in mind. M3, along with some other material, worked rather perfectly. Plus I can't deny that the Carnifex played a huge role. So M3 went on the table and M1 went back on the shelves.

In some ways, I do wish I had read M1 before I had picked up M3. I had picked both modules up around 10-13 years ago while looking for a good epic level adventure for my kids then D&D 3.x game. They were into the epic levels of D&D 3, with the lowest level at 24 and the highest at 29. They were on this huge campaign against what they thought was the machinations of Tiamat. M1 was very good choice since I love the idea of flying ships (D&D should be FANTASTIC after all) but the base plot didn't work for the adventure in mind. M3, along with some other material, worked rather perfectly. Plus I can't deny that the Carnifex played a huge role. So M3 went on the table and M1 went back on the shelves.