Shiver – Role-playing Tales in the Strange & the Unknown

Shiver – Role-playing Tales in the Strange & the Unknown is a fast-playing, dramatic, and generic horror roleplaying game. Want to play a scenario of teenagers camping out at Lake Blood being stalked by a masked slasher? Inhabitants of a small town caught up in a zombie outbreak? A race through Transylvania being harried by vampires? Villagers oppressed by a demonic cult operating out of the nearby castle in medieval Italy? A rescue team dropping onto a colony in the far future and discovering it to be infested by strange aliens? Townsfolk stalked by werewolves and a witchfinder in seventeenth century England? Investigators making enquiries in a New England seaside resort rumoured to be home to a fish cult? Published by

Parable Games,

Shiver can do all of these and more. The roleplaying game combines simple, thematic mechanics built around archetypal characters and a simple propriety dice mechanic, combined with a Doom Clock which escalates the tension and a wide selection of classic, nasty monsters that really know how to hit back.

A Player Character in

Shiver is defined by an Archetype, six Core Skills, one or more Abilities, and a Fear. There are seven Archetypes—the Warrior, the Maverick, the Scholar, the Socialite, the Fool, the Weird, and the Survivor—and each emphasises one of the six Core Skills and provides three Paths, each of which provides ten Tiers of Abilities as the character gains experience and goes up a Character Level. For example, the Maverick’s Paths are the Thief, the Assassin, and the Ranger. The Tier One Ability for all Mavericks is Dodge, but the Tier Two Ability for the Thief is Sneaky, for the Assassin, Sneak Attack, and for the Ranger, Covering Fire. An option is given that when a Player Character reaches Tier Five, he can either carry on in his own Archetype or switch to another one altogether and become a Hybrid, though this also means that he has a Fatal Flaw as a troubled character.

The six Core Skills—effectively both skills and attributes—are Grit, Wit, Smarts, Heart, Luck, and Strange. Grit represents a character’s physical capabilities; Wit covers physical dexterity; Smarts is his intellect and capability with investigation and technology; Heart is his charisma and charm; Luck is his good fortune and the random of the universe; and Strange is his capacity for using magic, psychic powers, and so on. Of the Archetypes, the Fool relies upon Luck rather than a specific Core Skill; the Weird is the strange individual who might follow the Eldritch, Spiritualist, Psionic, or Body Horror Path; and Survivor is a generalist who might follow the Chosen/Leader, Survivalist, or Cockroach Path, the desperate, cowardly type. In addition, a Player Character has a Luck Bank for storing Luck—one for all Archetypes, except for the Fool, who has space for three; a current Fear status—either Stable, Afraid, or Terrified; and a Lifeline—Weakened, Limping, Trauma, and Dead—which is the same for all Archetypes.

To create a character in

Shiver, a player selects an Archetype, a Background which adds a unique Ability and a Flaw. He also adjusts one Core Skill in which his character is deficient. It really is as fast as that. The longest step is noting it all down. Of course, playing a character at a higher Tier will take a longer because the player needs to choose more Abilities, but not by much.

Henry Brinded

Archetype: Scholar

Path: Academic (Tier One)

Abilities: Medic!

Background: The Nerd

Ability: Run Away! Flaw: Weak

Fear: Ligyrophobia

Grit: 2 Wit: 3 Smarts: 5 (Talent: 1) Heart: 3 Luck: 3 Strange: 3

Mechanically, Shiver uses a dice pool system of six-sided dice, their faces marked with the symbols for the roleplaying game’s six Core Skills—Grit, Wit, Smarts, Heart, Luck, and Strange. To these are added Talent dice, eight-sided dice marked with Luck and Strange symbols. (The rules include a conversion guide for using standard six-sided and eight-sided dice, but if the group still wants to use the dice system, there is an online

dice roller.) When he wants his Player Character to undertake an action, he assembles a dice pool based on the action and its associated Core Skill plus Talent dice if the Player Character has in that Core Skill. Further dice can be added or deducted depending on whether the Player Character has Advantage or Disadvantage, an Ability which applies, or the player wants to spend his character’s Luck, and on the character’s Fear status.

The aim is to roll a number of symbols or successes in the appropriate Core Skill, the Challenge Rating ranging from one and Easy to five and Near Impossible. If the player rolls enough, then his character succeed; if he rolls two Successes more than the Challenge Rating, it is a Critical Hit; and if a player rolls three or more dice and every symbol is a success, this is Full House. In combat, a Critical Hit doubles damage and a Full House triples it, but out of combat the Director—as the Game Master is known in

Shiver—will need to suggest other outcomes for both. If Luck symbols are rolled, one can be saved in the Player Character’s Luck Bank for later use, but if two are rolled, they can be exchanged for a single success on the current skill roll, or they can be used to turn the Doom Clock back by one minute. A failed roll does not necessarily mean that the Player Character fails as he can use other means to succeed at the task if his rolls enough successes in another Core Skill for that task, though this requires some narrative explanation. However, a failed roll has consequences beyond simply not succeeding—each Strange symbol rolled pushes the Doom Clock up by a minute…

For example, the scholar Henry Brinded has found a tome written in Latin containing a spell which he thinks will dispel the monster stalking the halls of the college where he teaches. He can hear the thing getting closer and desperately intones the spell direct from the book. Henry’s player will roll the five dice for his Smarts plus its Talent die and the Director will sets Challenge rating at two. However, Henry is at a Disadvantage because he is intoning from the tome in a hurry and because he has not had the time to study either the tome or the spell. This would reduce the number of Smarts dice his player would roll to four, but Henry has one Luck in his Luck Bank and uses that to counter the Disadvantage. He rolls one Grit, one Smarts, and three Luck on the Core Skill dice and two Luck on the Talent die. This gives him one Smarts and would be a failure except for the five Luck. Henry’s player changes two of the Luck into a Smarts, guaranteeing his successful casting of the spell, adds a third Luck to Henry’s Luck Bank, and the last two he uses to move the Doom Clock back one minute…Combat uses the same mechanic with monsters and enemies—and the Player Characters when they are attacked—using the same Challenge Rating as skill tests. It is Turn-based, with the Director deciding whether each Player Character is acting First, in the Middle, or Last, depending upon their situation and what they want to do. Players are encouraged to be organised and know what their characters are capable of, the surroundings for the battle, and so on, in order to get the best out of their characters. With every Player Character possessing the same Lifeline (the equivalent of sixteen Health Points), combat can be simply nasty or nasty and deadly, depending upon the mode. In Survivor Mode, a Player Character who loses all of his Health Points is at Death’s Door and his player rolls his Luck Pool to survive until he dies or help arrives. In Nightmare Mode, every four Health Points has a negative effective upon the Player Character, such a as reduction in his Core Skills at Weakened, his movement at Limping, and so on, all the way down to no Health Points and dead—no being at Death’s Door. Depending on the scenario, death though need not be end though. A Player Character could become a ghost and continue to provide help from the afterlife or even become an antagonist!

Fear in

Shiver uses the same Challenge Rating system and mechanics. A Fear Check is made with a Player Character’s Strange Dice, and if the player fails the check, the character becomes Afraid, and if Afraid, becomes Terrified. If Afraid, a Player Character loses one die from all Core Skills, and two if Terrified. This temporary, and a Player Character can get rid of the effects of Fear be escaping or vanquishing the threat, steadying himself (this requires another Fear Check), or another Player Character uses an Ability to help him.

Narratively,

Shiver is played out against a Doom Clock. This at eleven o’clock at night and counts up minute by minute to Midnight and the Player Characters’ inevitable Doooommm! However, at ‘Quarter Past’, ‘Half Past’, ‘Quarter To’, and ‘Midnight’ certain events will happen, these being defined in the scenario or written in by the Director. So if camping at Lake Blood, a storm might break out at ‘Quarter Past’, then the strange old man who actually knows more than he is letting on might be abducted at ‘Half Past’, a tree fall on the Player Characters’ van at ‘Quarter To’, and then ‘Midnight’, the Serial Killer switch to chasing the Player Characters rather than stalking them. In general the Doom Clock will tick up due to the actions of the Player Characters, whether that is because of a failed skill check with Strange symbols, a failed Fear Check, abilities for the Weird Archetype, Background Flaws, or simply interacting with the wrong things in game. What this means is that dice rolls become even more uncertain, their outcome having more of negative effect potentially than just failures, but this is all in keeping with the genre. However, just as the Doom Clock can tick up to ‘Midnight’ through the Player Characters’ actions. It can also be turned back due to their actions. Rolling two Luck on skill checks, reaching Story Milestones, finding clues and important items, and certain Abilities can all turn the Doom Clock back.

Just as the Doom Clock racks up the tension and triggers bad events, it can also trigger positive events. Some Archetypes have Abilities which can only be used ‘Once Per Doom Quarter’ (others can only be used ‘Once Per Doom Cycle’), whilst the Weird Archetype in particular has Abilities which require the Doom Clock to tick up and trigger. This does make the Weird Archetype a little more complex than the other Archetypes to play and the Abilities are not always going to be helpful to the other Player Characters.

For the Director, there is good advice on her role, setting up a game and setting its tone, building and structuring a story, getting the Player Characters involved, adjudicating the rules, handling the Doom Clock and designing events around it, handling Player Character deaths, and rewarding the Player Characters. The latter ranges from handing out Advantage dice and turning the Doom Clock back to their finding weapons and equipment and being given Levels Up. The latter is based on narrative events and each gives an Archetype access to new Abilities and/or Core Skill increases. In a campaign, it might be as often as at the end of a chapter, but in a one-shot it might be as fast as once a Quarter on the Doom Clock! In addition, the Director is given a huge list of equipment from baseball bats and books of banishment to stake rifles and zweihanders, from acid flasks and bear traps to the Helsing crossbow and Excalibur, and from berserker’s bear and bomb disposal suit to jet packs and symbiotic entities, there is just everything she needs to equip her Player Characters, NPCs, and seed a scenario across an array of genres and time periods.

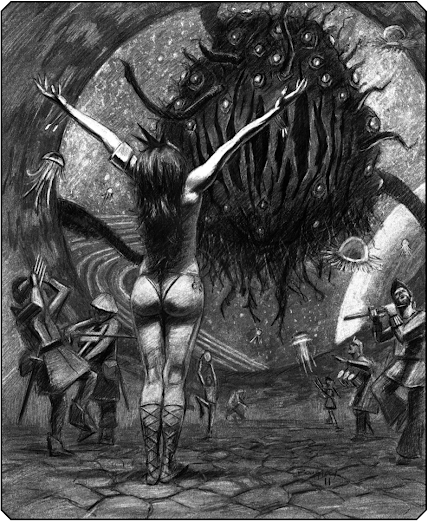

Similarly, the Director has a big list of monsters and enemies to choose from. They categorised under Slashers, Shapeshifters, Dark Magic, Demonic, Cosmic Horrors, Eldritch Entities, Spirits, Aliens, Vampyrs, and Zombies. All are fully detailed and reflect a wide range of threats and stories that they lend themselves to, and further support the different subgenres of horror that

Shiver is designed to cover. In addition to their own Abilities, these monsters and enemies can use Reaction Tables which the Director rolls on whenever a Player Character strikes them in combat. This requires a roll of a single Skill die, and might see a Bruiser type retaliating a slashing attack that does one Blunt damage if the Grit symbol is rolled or Dracula turning into a Cloud of Bats and flitting away on the roll of a Wit symbol. Apart from the Reaction table for Dracula, the Reaction tables are all generic and include a no effect result for rolling the Luck symbol—except for Dracula in which case, he gets hit ‘Right in the Kisser’ and prevents him from making an infect attacks on the next round due to the blow on his fangs! There is advice too for creating Reaction tables for other monsters. Lastly, there is a scenario, ‘Corporate Risers’, which casts the Player Characters as lowly employees at a corporate research centre when there is an outbreak of the zombies. It is a decent scenario which gives a chance for the Director and her players to experience

Shiver in a one-shot. It includes notes on character types to create for it, or the player could use those from the

SHIVER RPG Quick-start Guide.

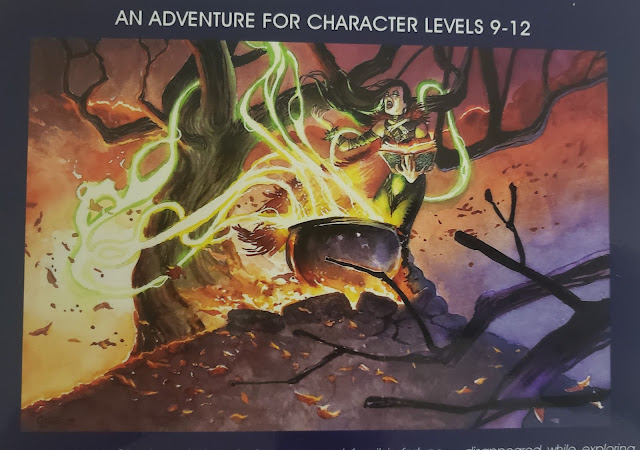

Physically, Shiver – Role-playing Tales in the Strange & the Unknown is a good-looking book. The artwork is excellent, done in a style similar to that of Mike Mignola and his

Hellboy comic, and very much showcases the type of horror stories that Shiver was designed to handle. The writing is clear, but in places, the roleplaying game could have been slightly better organised to make things easier to find.

If there is an issue with

Shiver, it lies its generic nature and sometimes in the limited choices offered by the Archetypes. The generic nature means it has to work harder at some subgenres than others and not all of the Abilities offered by the Paths for the Archetypes necessarily fit. This is all due to

Shiver having to cover a wide variety of horror types and elements and so some nuances may be lost. However, there are nuances to be found in the mechanics, especially in the Archetype and Ability design as they interact with the Doom Clock. Another issue is that as written, it does feel primarily written for one-shots, so it would be interesting to see what a campaign for

Shiver looks like.

Shiver – Role-playing Tales in the Strange & the Unknown is great for one-shots and convention games too. Its simple, fast-paced mechanics hide some nice little nuances—especially in the design of Archetypes and the way that they and the dice rolls interact with the Doom Clock, which means that the players are not just going to be kept on their toes by the monsters, but also by their own dice rolls, as the tension racks up and the clock ticks down... If a group is looking for a generic horror roleplaying game that veers a little towards the Pulp and which can do a range of horror subgenres, especially film-inspired ones, then

Shiver – Role-playing Tales in the Strange & the Unknown is a perfect choice.

What is it?

What is it?