I Return

Sorry about the lack of posts in recent months, my computer went down and I had a devil of a time getting it fixed. That's past now. will have something to post again soon.

Original Roleplaying Concepts

Sorry about the lack of posts in recent months, my computer went down and I had a devil of a time getting it fixed. That's past now. will have something to post again soon.

finally, after a really much too long time, I have a nice computer instead of an awful tablet that couldn't run the blogger app.

and so, something fun; a Vovelle for finding what stars are shining by month in Eldorath. clearly it isn't finished yet, but you get the idea. vovelles were a common astronomical item in old books.

Continuing my "Spirit of '76" mini-campaign I want to get some more details on who my "big bad" might be. I say might, because I am not 100% sure yet what I want to do with her save for being the mastermind behind the plot. I know I want to make what she wants to do sound reasonable and something that most people would want to support. That is if her plan didn't involve the death of millions.

Given the name of the series, I figure she would fit in fine as the first person of European descent born in the colonies. She is also the reason I have scrapped many of the ideas I had for Spirit of 76 (including other NPCs) in favor of newer ones. Still planning on four adventures, but I only have the first two figured out.

I spoke about Virginia Dare briefly before. She is the immortal enemy of Valerie Beaumont. Though their relationship is quite a complicated one. She wants to kill Valerie, but Val doesn't really want to kill her. I liken their relationship (as it is growing in my mind now) as similar to Holmes and Moriarty or The Doctor and the Master.

Here she is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Virginia Dare

Virginia DareFate Points: 1d10

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +6/+4/+2Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: +1Saves: +5 to death saves. +2 to all others.Survivor Skills (8th level)

Skills

Research, Insight, History (x2)

--

Virginia Dare has survived some of the worst times this country has seen. She is brilliant and her own special abilities to understand and charm others to get her into positions where she can leverage her intellect the best. She learns what people want and she finds a way to get it to them, for a price.

She prefers to work behind the scenes but she has amassed a powerbase that when she decides to play her hand it will have devastating effects.

I just need to figure out what that is. I have an idea, but not sure how to make it work just yet. Both in-game and for the game.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

Name: The Hammersmith HauntingPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: The Hammersmith HauntingPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.Going forward in time to another campaign I have been tossing around for a while. This one is set in the Summer of 1976. I don't have much planned yet save that it involves an increased upswing in demonic and supernatural attacks and related phenomena.

Ideally, I'd love to be able to use a lot of weird shit that made the 70s one of the best decades for occult happenings. My goal here is to try to figure out what this campaign/set of adventures is all about.

So let's start with the character that made me want to do something in this decade; Carl Kolchak, The Night Stalker. Besides, it is the 50th Anniversary of the Night Stalker TV series.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Carl Kolchak

Carl Kolchak Fate Points: 1d6

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +3/+1/0Melee bonus: 0 Ranged bonus: +1Saves: +4 to death saves. +2 to all others.Survivor Skills (8th level)

Skills

Research, Insight, Notice (x2)

--

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo— In 1982, TSR, Inc. published its first Science Fiction roleplaying game, Star Frontiers. Now TSR, Inc. as stated in ‘The SF ‘universe’’ (Dragon #74, June 1983), “TSR had previously published SF-oriented role-playing games, most notably the GAMMA WORLD® game and METAMORPHOSIS ALPHA game, but these two games are post-apocalyptic visions of the future.” and “While they are certainly interesting and undoubtedly SF in nature, neither of these games fully realizes the potential of a science-fiction setting. A star-spanning civilization, interstellar spacecraft, strange aliens, and adventures on a myriad of bizarre and challenging new worlds are the elements of a classic SF framework. The possibilities for adventure in such a “universe” are nearly limitless. The STAR FRONTIERS game, unlike its predecessor SF titles from TSR, is able to appreciate these possibilities.” So as the very first actual Science Fiction roleplaying game from TSR, Inc., Star Frontiers was very much intended to play off the boom in Science Fiction and space adventure which followed in the wake of Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, for example on the big, as well as Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century on the small screen. It would take a full year before it reached that potential with the Knight Hawks boxed supplement which added spaceships and spaceship combat to the roleplaying game, but in the meantime, Star Frontiers offered planetside adventure with stripped down, straightforward set of mechanics and rules designed to introduce new players to the hobby and Science Fiction roleplaying to more experienced players—especially if their only experience was Dungeons & Dragons.

In 1982, TSR, Inc. published its first Science Fiction roleplaying game, Star Frontiers. Now TSR, Inc. as stated in ‘The SF ‘universe’’ (Dragon #74, June 1983), “TSR had previously published SF-oriented role-playing games, most notably the GAMMA WORLD® game and METAMORPHOSIS ALPHA game, but these two games are post-apocalyptic visions of the future.” and “While they are certainly interesting and undoubtedly SF in nature, neither of these games fully realizes the potential of a science-fiction setting. A star-spanning civilization, interstellar spacecraft, strange aliens, and adventures on a myriad of bizarre and challenging new worlds are the elements of a classic SF framework. The possibilities for adventure in such a “universe” are nearly limitless. The STAR FRONTIERS game, unlike its predecessor SF titles from TSR, is able to appreciate these possibilities.” So as the very first actual Science Fiction roleplaying game from TSR, Inc., Star Frontiers was very much intended to play off the boom in Science Fiction and space adventure which followed in the wake of Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, for example on the big, as well as Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century on the small screen. It would take a full year before it reached that potential with the Knight Hawks boxed supplement which added spaceships and spaceship combat to the roleplaying game, but in the meantime, Star Frontiers offered planetside adventure with stripped down, straightforward set of mechanics and rules designed to introduce new players to the hobby and Science Fiction roleplaying to more experienced players—especially if their only experience was Dungeons & Dragons.Wrapping up my tour of the Victorian era with the original dynamic duo of Holmes and Watson. Today I focus my sights on the good Dr. John Watson.

John Watson is an interesting character. By all rights, he would have been the star of his own serials; British Army officer, Doctor, not a bad detective in his own right and good with a service pistol. He was also smart, just not as smart as Holmes.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Dr. John Watson

6th level Veteran (Human)Fate Points: 1d8

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +4/+2/+1Melee bonus: +1 Ranged bonus: +1Saves: +2 to all savesSkills

Medicine x2, Science, Insight, Notice

--

Dr. Watson is a veteran with a lot of training in medicine. This covers his character rather well.

I hope this gets me motivated for some more Sherlock Holmes posts.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Salo’s Glory is a near future Science Fiction scenario for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. The eleventh title from publisher Stygian Fox, it is a one-shot designed for three to six players and be played in a session or two. Mankind has expanded and explored to the furthest reaches of the Solar System, and begun to go beyond. One such exploratory vessel is the Galilee Heavy Industries I.E.V. Tryphena. Here on the edge of interstellar space, the crew of the Tryphena make not one, but four astounding mysteries. First is the presence of a ship identical to their own, also named the Tryphena, but powered down, seemingly abandoned, orbiting a cold planetoid. The second, third, and fourth consist of signals. One signal is the distress signal coming from the abandoned ship’s shuttle, the other two come from stone structures at the north and south poles of the planetoid. The question, what happened to the crew of the other Tryphena? Why did they abandon their ship? What exactly lies on the surface of the planetoid?

Salo’s Glory is a near future Science Fiction scenario for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. The eleventh title from publisher Stygian Fox, it is a one-shot designed for three to six players and be played in a session or two. Mankind has expanded and explored to the furthest reaches of the Solar System, and begun to go beyond. One such exploratory vessel is the Galilee Heavy Industries I.E.V. Tryphena. Here on the edge of interstellar space, the crew of the Tryphena make not one, but four astounding mysteries. First is the presence of a ship identical to their own, also named the Tryphena, but powered down, seemingly abandoned, orbiting a cold planetoid. The second, third, and fourth consist of signals. One signal is the distress signal coming from the abandoned ship’s shuttle, the other two come from stone structures at the north and south poles of the planetoid. The question, what happened to the crew of the other Tryphena? Why did they abandon their ship? What exactly lies on the surface of the planetoid?Today I want to wrap up my tour of the Victorian era with two of my favorite characters of the time, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson.

I have, sitting on my hard drive or a flash drive somewhere the stats for Holmes for every Victorian-era game I have ever played. I keep meaning to post them and never get around to it. So of course today is a set of stats I am coming up with now.

The issue with doing Holmes in many games, but modern occult ones, in particular, is that Holmes does not live in a magical world. He lives in a world with predictable laws of science that follow predictable patterns. This is what makes him so good at what he does, he can see these patterns and connections. Holmes works because the world is mundane and what he does looks like magic.

For NIGHT SHIFT there is no one class that would do him justice. While I could get away with making him a 10th level Survivor (and I feel 10 levels is right) he is missing a couple of key ingredients. So time to try another multiclass.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Jeremy Brett as Sherlock HolmesSherlock Holmes

Jeremy Brett as Sherlock HolmesSherlock HolmesFate Points: 1d10

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +5/+3/+2Melee bonus: +2 Ranged bonus: +2Saves: +4 to death saves. +2 to all others.Stealth Skills (8th level)

Sage Abilities

Survivor Skills (factored in above); Mesmerize Others; Lore; Languages (18); Spells* (to Holmes they are not "spells" merely "advanced techniques.")

Spells

First level: Command, Detect Snares & Pits

Second level: Find Traps

Skills

Athletics (Bartitsu), Sleight of Hand, Research, Science, Insight, Notice

--

Holmes combines a variety of class abilities and skills to create one investigator. Would an "Investigator" class have been better? Not really. In this case, I feel the mix of classes and skills point to obscure training and thus a unique character. Holmes is certainly that.

If you are interested in playing Sherlock Holmes in a game system more suited to the world he lived in then might I suggest both Victoria and Baker Street: Roleplaying in the world of Sherlock Holmes. Both are very fine games.

Want to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

Published by Lantern’s Faun, Into the Bronze: Sword & Sorcery RPG in Bronze Age Mesopotamia is a minimalist roleplaying game built on the architecture of Into the Odd. As the title suggests, it is set in the Bronze Age in Mesopotamia on the plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Here the first city states were founded, here the first men and the women strode forth to explore the lands between the first two great rivers known to mankind, to enter the silent, gloomy valleys where demons and their acolytes hid and devised their evil plans, here they would encounter the very gods of Sumeria, and here they would build the first great civilisations. As those first men and women to stride the land, the Player Characters are Sumerian ‘Bounty Hunters’ those willing to go forth and undertake dangerous tasks—explore the unknown, hunt down criminals, kill monsters, and more… In return, their wicker baskets will be filled with great wealth—treasures, secrets, and favours. With their treasures, their wealth, and their secrets, they not only have the potential to make their mark on the world, but go onto to stamp on the world by building and constructing civilisation around them.

Published by Lantern’s Faun, Into the Bronze: Sword & Sorcery RPG in Bronze Age Mesopotamia is a minimalist roleplaying game built on the architecture of Into the Odd. As the title suggests, it is set in the Bronze Age in Mesopotamia on the plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Here the first city states were founded, here the first men and the women strode forth to explore the lands between the first two great rivers known to mankind, to enter the silent, gloomy valleys where demons and their acolytes hid and devised their evil plans, here they would encounter the very gods of Sumeria, and here they would build the first great civilisations. As those first men and women to stride the land, the Player Characters are Sumerian ‘Bounty Hunters’ those willing to go forth and undertake dangerous tasks—explore the unknown, hunt down criminals, kill monsters, and more… In return, their wicker baskets will be filled with great wealth—treasures, secrets, and favours. With their treasures, their wealth, and their secrets, they not only have the potential to make their mark on the world, but go onto to stamp on the world by building and constructing civilisation around them. Mouth Brood is an exploratory horror scenario set in the wilds of Canada in the Yukon on the Kaskwulsh Glacier. Here a strange discovery has been made—a great biodome jutting out of the ice, revealed no doubt due to the effects of global warming and the melting of the glacier. Buried here for millennia, the biodome has clear walls, but what is inside is hidden by leaves and mist and smears of algae. There is though, something moving inside. Clicking and humming and crying. Thousands of things. Millions of things. Are they alien? Are they vestiges of a prior epoch? Are they the results of an abandoned biological project—corporate or governmental? With the discovery of the biodome, Astralem Biotech has been sent a biologists to enter the structure, investigate and catalogue its contents, and above all, return with five live specimens with promises of a bonus for each extra one brought back. What will the team discover? Is it safe? Is it dangerous? Will the team survive?As with other scenarios from Games Omnivorous, Mouth Brood is a system agnostic scenario, but unlike previous scenarios—The Feast on Titanhead, and The Seed, but like Cabin Risotto Fever before it, this scenario takes place in the modern world rather than a fantasy one. Where Cabin Risotto Fever was set in northern Canada in 1949, the setting for Mouth Brood is the Canada of the here and now—although it does not have to be. As a module, Mouth Brood combines Science Fiction and Horror in its investigation, and like the other titles in the ‘Manifestus Omnivorous’ series is systems-agnostic. Although a modicum of stats is provided to suit a Dungeons & Dragons-style roleplaying game, Mouth Brood would work with, and be easy to adapt to any number of modern or Science Fiction roleplaying games. These include Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition or Chill, third Edition, as well as Alien: The Roleplaying Game, Traveller, and MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. The point is, Mouth Brood need not be set in Canada, it could be shifted to the Antarctic or the Himalayas, or it could even shifted off world entirely, say to Mars or even to a planet in a different system (although that would break one of its rules listed below, but nevertheless, the possibility is there). Its set-up is simple, flexible, and easy for the Game Master to adjust as necessary. However, just like The Feast on Titanhead, The Seed, and Cabin Risotto Fever before it, Mouth Brood adheres to the Manifestus Omnivorous, the ten points of which are:

Mouth Brood is an exploratory horror scenario set in the wilds of Canada in the Yukon on the Kaskwulsh Glacier. Here a strange discovery has been made—a great biodome jutting out of the ice, revealed no doubt due to the effects of global warming and the melting of the glacier. Buried here for millennia, the biodome has clear walls, but what is inside is hidden by leaves and mist and smears of algae. There is though, something moving inside. Clicking and humming and crying. Thousands of things. Millions of things. Are they alien? Are they vestiges of a prior epoch? Are they the results of an abandoned biological project—corporate or governmental? With the discovery of the biodome, Astralem Biotech has been sent a biologists to enter the structure, investigate and catalogue its contents, and above all, return with five live specimens with promises of a bonus for each extra one brought back. What will the team discover? Is it safe? Is it dangerous? Will the team survive?As with other scenarios from Games Omnivorous, Mouth Brood is a system agnostic scenario, but unlike previous scenarios—The Feast on Titanhead, and The Seed, but like Cabin Risotto Fever before it, this scenario takes place in the modern world rather than a fantasy one. Where Cabin Risotto Fever was set in northern Canada in 1949, the setting for Mouth Brood is the Canada of the here and now—although it does not have to be. As a module, Mouth Brood combines Science Fiction and Horror in its investigation, and like the other titles in the ‘Manifestus Omnivorous’ series is systems-agnostic. Although a modicum of stats is provided to suit a Dungeons & Dragons-style roleplaying game, Mouth Brood would work with, and be easy to adapt to any number of modern or Science Fiction roleplaying games. These include Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition or Chill, third Edition, as well as Alien: The Roleplaying Game, Traveller, and MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. The point is, Mouth Brood need not be set in Canada, it could be shifted to the Antarctic or the Himalayas, or it could even shifted off world entirely, say to Mars or even to a planet in a different system (although that would break one of its rules listed below, but nevertheless, the possibility is there). Its set-up is simple, flexible, and easy for the Game Master to adjust as necessary. However, just like The Feast on Titanhead, The Seed, and Cabin Risotto Fever before it, Mouth Brood adheres to the Manifestus Omnivorous, the ten points of which are:As we have come to expect for scenarios from Games Omnivorous, Mouth Brood adheres to all ten rules. It is an adventure, it is system agnostic, it takes place on Earth, it has one location, it has the one monster (though like the older scenarios, those others that appear are extensions of it), it includes both Saprophagy—the obtaining of nutrients through the consumption of decomposing dead plant or animal biomass—and Osteophagy—the practice of animals, usually herbivores, consuming bones, it involves a voracious eater, the word count is not high—the scenario only runs to twenty-eight pages, and it is presented in two colours—in this case, a dark green and greenish-blue over snowy white. Lastly, where previous entries in the series have exhibited Rule #10, it is debatable whether or or not Mouth Brood fails to exhibit good taste—though perhaps that may ultimately be up to how the players and their characters react to it.

The scenario is self-contained detailing a biodome and its almost fizzing, swarming ecology filled with strange creatures that the intruding Player Characters—or indeed anyone—will have seen before. It consists of the outer cover with a map of the biodome on the inside, descriptions of its locations layered out over three levels, from the Undergrowth up through the Canopy to the Emergent, plus a lengthy Bestiary of some eighteen creatures and species. Like all Manifestus Omnivorous titles, it is bound with an elastic band and thus all of the pages can be separated. The advice for the Game Master is to use the Undergrowth, Canopy, and Emergent pages as a screen, and refer to the pages of the Bestiary during play. There is a set-up too, that of Astralem Biotech team, and there are notes on the roles, gear, and advantages of the Expedition Leader, Ecologist, Micro-biologist, and the Bio-Mathematician. These can be copied and given to the players, but the Game Master can also use them as prompts to create pre-generated Player Characters for the roleplaying game of her choice.

Mouth Brood is also a hex-crawl—though very much a mini-hex-crawl, there being seven locations for each of the biodome’s three levels (Undergrowth, Canopy, and Emergent). Each of the hexes is given a thumbnail description, but the bulk of Mouth Brood, twenty-four pages out of its thirty-six, is devoted to its Bestiary. Each entry is accorded a fantastic illustration, a description, a table of things it is doing or is being done to it, and details of what it is doing when observed. They lifeforms of all sorts, such as Acris Motorium, a semi-mobile plant with acrid acid for its sap; the similarly motile Cryptostoma Dilitatus, a swarm-like organism which can contract and spread, and stings in proportional response to contact with it; and the Velox Sanguinus, the brachial apex predator with two sets of jaws, one in its swiveling head, the other in its belly. There is something quite verdant, fetid, and even feverish about the inventiveness of all of these creatures, which could be taken from the pages of Mouth Brood and used elsewhere if the Game Master so desired.

Mouth Brood is primarily a setting, a small environment awaiting the intrusion of the Player Characters, the creatures and species in the biodome reacting to their invasive presence. There is a slight here, that of the biological team collecting samples (and a bit more), but as an exploratory scenario and a hexcrawl scenario, Mouth Brood is very much player driven, the Game Master having to the extensive ecology react to them for much their Player Characters’ explorations. In some ways, this does require a fair bit of preparation upon the part of the Game Master, who has to understand how each of the different species will react to the Player Characters’ presence and actions. In terms of play, there will be a lot of movement and then just being still and observing, such there is almost something sedentary to the scenario. That will probably change once the Player Characters come to the notice of the biodome’s predators. If using pre-generated Player Characters, the Game Master might also want to add some storyhooks and relationships to them, not only to encourage interaction, but also to ramp up the tension when the dangers of the ecology within the biodome become apparent.

Physically, as with the other titles in the Manifestus Omnivorous series, Mouth Brood is very nicely presented. The cover is sturdy card, whilst the pages are of a thick paper stock, giving the book a lovely feel in the hand. The scenario is decently written, if a little spare in places, but the artwork is excellent and when shown to the players, should have them exclaiming, Ugh what’s that?”, at just about every entry in the Bestiary.

Inspired by films such as Annihilation and Roadside Picnic, Mouth Brood presents a hellishly febrile ecological unknown, its self-contained nature suggesting that its horror is all inside, when ultimately, the true horror is realising the consequences of what would happen if it were outside…

Sticking with my Victorian-era and moving south from Lincoln's ghost to New Orleans and her voodoo queen.

But "Wait," you say. "Marie Laveau died in 1881. Long before your 1890s game." True. That's what people believe. There is a lot of confusion about her exact date of death. There is even doubt as to where she is actually buried. So for my purpose, this works for her faking her death so she could go on do her thing. Besides there have been rumors that she survived her own death for years.

Marie Laveau is not just synonymous with Voodoo she is very much part of New Orleans herself. No New Orleans. No Marie Laveau. Also, what was she exactly? She was the self-proclaimed Voodoo queen of New Orleans sure, but what *is* that in terms of NIGHT SHIFT? A Witch? A Theosophist? Sage?

No Marie is something special and in NIGHT SHIFT terms she is something from the new Night Companion book. She is an immortal Spirit Rider.

Here he is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Marie Laveau

6th level Spirit Rider (Supernatural, Immortal)

6th level Spirit Rider (Supernatural, Immortal)Fate Points: 1d8

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +4/+2/+1Melee bonus: +0 Ranged bonus: +2; Wisdom is added to Spell attacks (+6)Saves: +3 Death Saves and area effects, +2 to Wisdom and Charisma-based savesWant to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!

How do you like your GM Screen?

The GM Screen is essentially a reference sheet, comprised of several card sheets that fold out and can be stood up to serve another purpose, that is, to hide the GM’s notes and dice rolls. On the inside, the side facing the GM are listed all of the tables that the GM might want or need at a glance without the need to have to leaf quickly through the core rulebook. On the outside, facing the players, is either more tables for their benefit or representative artwork for the game itself. This is both the basic function and the basic format of the screen, neither of which has changed very much over the years. Beyond the basic format, much has changed though. So how do I like my GM Screen?

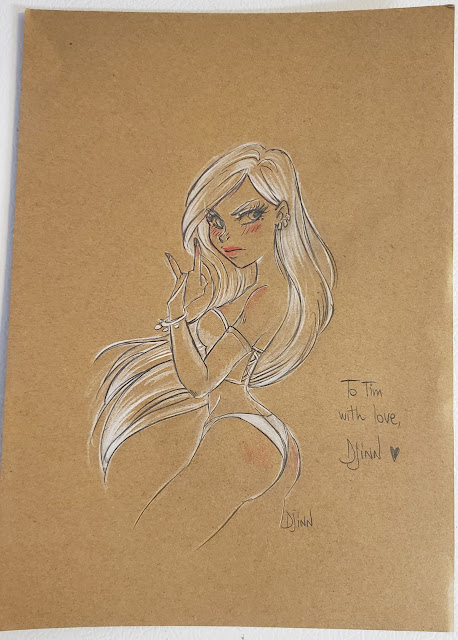

So how do I like my GM Screen?One of the things I feel is my privilege is the ability to share with you my readers and friends all the new and wonderful artists I can find. I love getting art and if I can help out an artist on the way, well that is even better.

But when the artist shares something with me? That is the best of all!

So imagine my delight when the postman rings my doorbell today to have me sign for a package from Italy!

I had just featured some art from Djinn in the Shade this morning on my Dirty Nellie write-up. She was the first artist I have ever had make some art for Nell.

And here is what I got!

Halloween

Halloween

Stickers!

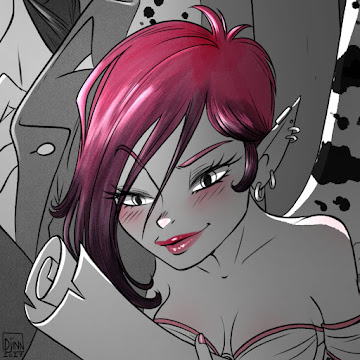

Stickers!Djinn also featured our witches in jail in a new bit of art this week to mark her "shadow ban" from Instagram for having "inappropriate art."

So I am thrilled to death with these!

You can find Djinn on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram (for now!), and most of all on her Pateron site. She was also one of my first Featured Artists here.

Thank you my friend for such wonderful art!

So far my dive into Dracula and then Victorian characters for NIGHT SHIFT has been a lot of fun. Also, my characters have largely been based on other people's characters or, in the case of Lincoln, real people.

Today I want to do one of my original characters (OCs for the kids online). She is also one of the characters I had in mind for the Supernatural character rules.

I had introduced you all to Dirty Nellie a few years back (2009!) for various Victorian-era games including Ghosts of Albion, Savage Worlds, and Victoriana 2nd Edition.

Briefly, she is a Street Faerie. These are members of the Fae that have chosen to live in cities. They are like pixies, complete with wings, but are more human-sized, if a bit shorter. Their wings look like those of the Peppered Moth. The obvious reason why is due to the case of the evolution of the peppered moth due to the Industrial Revolution. Just like the moth, these fae have adapted to the grim, gaslit streets of London.

Nell herself is a central figure in my Victorian games. She begins as a streetwalker but soon works her way up to running the notorious Gentleman's Club (in the Victorian sense of the term) "Mayfairs" in the late Victorian age. She is an occult information broker and nearly anyone who is anyone in the occult underworld owes her a favor. Knowledge is power and Nell knows everyone and knows what they know.

Here she is for Night Shift. NIGHT SHIFT is available from the Elf Lair Games website (hardcover) and from DriveThruRPG (PDF).

Nellie by Djinn in the ShadeDirty Nellie10th level Survivor (Supernatural, Faerie)

Nellie by Djinn in the ShadeDirty Nellie10th level Survivor (Supernatural, Faerie)Fate Points: 1d10

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +5/+3/+2Melee bonus: +1 Ranged bonus: +2Saves: +6 against magic and supernatural attacksWant to see more of the #CharacterCreationChallenge? Stop by Tardis Captain's Blog and the #CharacterCreationChallenge on Twitter for more!