Reinhold Timm - Cadmus Slaying the Dragon, 1618-1639

Artwork found at SMK Open.

Artwork found at SMK Open. Original Roleplaying Concepts

Artwork found at SMK Open.

Artwork found at SMK Open.  Locus: A roleplaying game of personal horror which explores themes of guilt, morality, and mystery. It asks each Player Character what it was that he did wrong and how he feels about it, what is wrong—or right and who says so, and presents him and his companions with a strangeness and mystery around them, that somehow, they must survive. It is a game of ordinary men and women, protagonists thrust into unsettling situations and nightmares, and exposed to mysteries that perhaps will push them to confront their own secrets. Published by Cobble Path Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it comes in two volumes—Player Guide and Director’s Guide*—and is inspired by psychological horror films such as The Descent, Triangle, Shutter Island, and others, rather than classic slashers like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Friday the 13th.

Locus: A roleplaying game of personal horror which explores themes of guilt, morality, and mystery. It asks each Player Character what it was that he did wrong and how he feels about it, what is wrong—or right and who says so, and presents him and his companions with a strangeness and mystery around them, that somehow, they must survive. It is a game of ordinary men and women, protagonists thrust into unsettling situations and nightmares, and exposed to mysteries that perhaps will push them to confront their own secrets. Published by Cobble Path Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it comes in two volumes—Player Guide and Director’s Guide*—and is inspired by psychological horror films such as The Descent, Triangle, Shutter Island, and others, rather than classic slashers like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Friday the 13th. Locus: A roleplaying game of personal horror which explores themes of guilt, morality, and mystery. It asks each Player Character what it was that he did wrong and how he feels about it, what is wrong—or right and who says so, and presents him and his companions with a strangeness and mystery around them, that somehow, they must survive. It is a game of ordinary men and women, protagonists thrust into unsettling situations and nightmares, and exposed to mysteries that perhaps will push them to confront their own secrets. Published by Cobble Path Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it comes in two volumes—Player Guide and Director’s Guide*—and is inspired by psychological horror films such as The Descent, Triangle, Shutter Island, and others, rather than classic slashers like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Friday the 13th.

Locus: A roleplaying game of personal horror which explores themes of guilt, morality, and mystery. It asks each Player Character what it was that he did wrong and how he feels about it, what is wrong—or right and who says so, and presents him and his companions with a strangeness and mystery around them, that somehow, they must survive. It is a game of ordinary men and women, protagonists thrust into unsettling situations and nightmares, and exposed to mysteries that perhaps will push them to confront their own secrets. Published by Cobble Path Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it comes in two volumes—Player Guide and Director’s Guide*—and is inspired by psychological horror films such as The Descent, Triangle, Shutter Island, and others, rather than classic slashers like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Friday the 13th. Macdeath is an adventure for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. Published by Critical Kit, it is designed for a party of four to five Player Characters of low- to mid-Level and is intended to be played in a single session, either as a one-shot or as part of an ongoing campaign. It involves a theatre troupe, a fairy circle, a performance, and a murder! Whilst self-contained, it would be easy to adapt Macdeath to the setting of the Dungeon Master’s choice, so long as the setting involves the fae and fairy-kind. Most fantasy roleplaying settings—especially for Dungeons & Dragons—feature this, but the Ravenloft setting would be particularly appropriate, as would any with a Renaissance feel. However it is used, Macdeath is fairly straightforward and involves a mix of investigation and interaction, with almost no combat.

Macdeath is an adventure for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. Published by Critical Kit, it is designed for a party of four to five Player Characters of low- to mid-Level and is intended to be played in a single session, either as a one-shot or as part of an ongoing campaign. It involves a theatre troupe, a fairy circle, a performance, and a murder! Whilst self-contained, it would be easy to adapt Macdeath to the setting of the Dungeon Master’s choice, so long as the setting involves the fae and fairy-kind. Most fantasy roleplaying settings—especially for Dungeons & Dragons—feature this, but the Ravenloft setting would be particularly appropriate, as would any with a Renaissance feel. However it is used, Macdeath is fairly straightforward and involves a mix of investigation and interaction, with almost no combat.

With the end of One Man's God on my mind, I wanted to make this week a little more special. To that end I wanted to spend some more time with Norse Myths and Vikings. So with on thing ending (almost) I have mental energy (or "Spell slots" as the kids say today) to do something a little newer.

With the end of One Man's God on my mind, I wanted to make this week a little more special. To that end I wanted to spend some more time with Norse Myths and Vikings. So with on thing ending (almost) I have mental energy (or "Spell slots" as the kids say today) to do something a little newer.I have long been a fan of the AD&D 2nd Ed. Historical References books. I have used the Celts one over and over again with many different versions of D&D and I have been pleased with it. The scholarship on these is a bit better than the Deities & Demigods, but I attribute this to a better budget and more space to explain what they were doing.

Also, the focus was a little different. The D&DG took myths and tried to fit them into the AD&D framework. The Historical References took the myths and described how to play an AD&D game in that world.

It's Norse Week so let's start at the beginning with HR1 the Vikings Campaign Sourcebook.

HR1 Vikings Campaign Sourcebook (AD&D 2nd Edition)

For today's review, I am only going to consider the PDF version of this book from DriveThruRPG. I lost or sold back my original in one of my moves or collection downsize. I will mention details from the physical book as I remember it, but my focus is on the PDF for the details. In most cases the material is 100% the same, the difference coming from the fold-out map, which is separate pages in the pdf.

HR1: Vikings Campaign Sourcebook (1992), by David "Zeb" Cook. Illustrations by Ned Dameron and cartography by David C. Sutherland III. 96 pages, black & white with full-color maps.

The first book of the Historical Reference series covers the Viking raiders of Scandinavia. It is not a separate game world per se, since it deals with Pagan Europe after the fall of Rome, but it is a fantastical Europe where dragons fill the seas, troll-blooded humans walk among us, and somewhere out there in the wilderness, a one-eyed man wanders the land.

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter covers the very basics, starting off with what people usually get wrong about the Vikings. These guys are not Hägar the Horrible or even the interpretations of Wagner. They do point out that "Vikings" are also not really a people, but a lifestyle that some people engaged in.

This section also covers how to use this book, specifically how to use this book about Vikings and the history of their raids with the AD&D 2nd Rules. We get into more specific details in the next chapters.

Chapter 2: A Mini-Course of Viking History

Starting with the raid at Lindisfarne in 793 CE the book covers a very basic history of the Northmen's lands, the lands they raided, and their culture and history. The focus here though is through the lens of an AD&D game, not a historical introduction. The book is clear on this.

Details are given, with maybe extra focus on England and France (though they are not called that yet) but that is fine. There is a very nice timeline running across the top of the pages of this chapter that is rather handy. The time period, roughly 800 to 1100 CE agrees with most of the scholarship on "Viking History" so that works fine for here as well.

There is a nice list of settlements and cities the Vikings targeted. Not a full list, but it gives you an idea of how much of Europe, Northern Africa, and even parts of Asia the Vikings would roam.

There is a page or so of suggested readings. Likely the best at the time. The chapter does set you nicely to explore these ideas further.

Chapter 3: Of Characters and Combat

Here we get into game writing proper. We start with what races you will find in a Viking-themed campaign. Obviously, we are talking mostly humans here. Humans can gain a "Gift" something that makes them special such as "Rune Lore" or "Bad Luck" or even a Seer. There is a new "race" the Troll-born. These are stronger than average humans due to troll-blood in their veins. They get a +1 to Strength, Constitution and Intelligence but a -1 to Wisdom and a -2 to Charisma. They have Infravision and are limited to 15th level in their classes. They are not born with Gifts.

Next, we cover the changes to the Character Classes from the PHB. Fighters on the whole tend to be unchanged as are Rangers and Thieves. Classes not allowed are Clerics, Paladins, Druids, and Wizards, though specialty mages are allowed if they are Conjurers, Diviners, Enchanters, Illusionists, Necromancers. While this could be a negative for some I like the idea of limiting classes for specific campaigns. Two new sub-classes of the Warrior are added, the Berserker and the Runecaster. Both do pretty much what you might suspect they do. The berserker is actually rather cool and while the obvious roots here are the barbarian and berserker monster from AD&D 1, there is enough here to make it work and be interesting too. Runecasters know runes as detailed in the next chapter.

The "forbidden" classes can be played, if they are outsiders.

Lip service is given to the detail that the Vikings were predominantly men. Though new archaeological finds are casting some doubt that they were exclusively so. This book does give some examples of how warrior women were known. They emphasize that player characters are always exceptional.

There is a section on names (including a list of names), homelands, and social class.

In the purist AD&D 2nd ed section, we get some new Proficiencies.

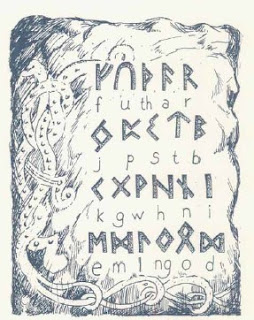

Chapter 4: Rune Magic

Chapter 4: Rune MagicThis covers Rune Magic. An important feature of Viking Lore. What the runes are and how to use them in AD&D 2nd Ed terms are given. A lot of these are minor magics, say of the 0-level or 1st-level spell use. I personally don't recall them being over abused in games, but they are a really nice feature to be honest.

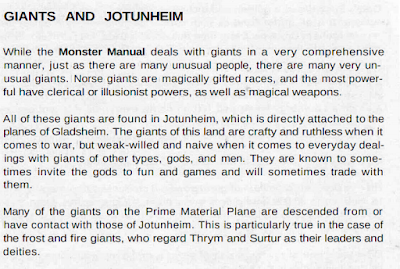

Chapter 5: ...And Monsters

Monsters are discussed here, starting with which existing monsters can be used from the AD&D 2nd Monstrous Compendium. Following this some altered monsters are given. For example, there is the Gengånger which is a zombie with some more details.

Dwarves and Elves are given special consideration, as are trolls and giants.

There is not however any "new" monsters in the AD&D 2nd Ed Monstrous Compendium format. We will get those in the Celts book, but that is next time.

The section is split with a "centerfold" map of Europe.

Chapter 6: Equipment and Treasure

Vikings were Vikings because of the treasure they sought. They also had the best ships in Europe at this time. So let's spend some time with these.

We start with a section on money. For the game's simplicity, these are reduced to a couple of systems. Coins are usually categorized by make-up and weight. There is some good material here really and something that most games should look into.

Treasure covers the typical treasures found. Also, treasure was a central piece of Viking lore; it was how chieftains paid their men, it was what they stole from others, and it was also how they were paid off NOT to steal. Some space is given to Magic Items as well. This is an AD&D game after all. Some "typical" magical treasure is discussed and some that are not found at all. A few new items are also detailed.

Chapter 7: The Viking Culture

This chapter gives us are biggest differences from a typical AD&D game. For illustrative purposes, we follow a young Viking, Ivar Olafsson, in a year of his life. Now I rather liked this because it gave me a character situated in his life and culture. While it is not the most "gamble" material it is good background material.

There is a section on Social Ranking and a little more on the role of Viking women. I think after 6 seasons of watching Katheryn Winnick kick-ass as Lagertha in Vikings, this section will be read and cheerfully ignored. That is great, but this bit does talk about, and support, the image that Viking women had it better than their counterparts in the rest of Europe.

We also get into the sundries, quite literally; Food, drink, homes, farms, and trade. There is a section on religion with lots of nods towards the AD&D 2nd Ed Legends and Lore.

Chapter 8: A Brief Gazetteer

AD&D 2nd Ed is celebrated not really for its advances in game design or rules, but rather the campaign worlds. This book, and this section, in particular, is a thumbnail of why these celebrations are merited. Or, as I call it, just give me a map! This section is more than a map and maybe not as much as the famed Mystara Gazetteers, but the relationship is not difficult to pick out.

This covers, rather briefly (as it says in the title), the lands the Vikings would roam to. And there are a lot of those! In addition to the lands of Europe, Africa, Asia, and yes even North America, we get the fantastic worlds of the Vikings. If I had done this book this would have been Chapter 2 or 3 at the very least. This chapter is all too brief in my mind.

We get a longship design at the end and in the PDF what was the fold-out map.

--

So in truth a really fun resource. The AD&D game material is there, but this book could be used with pretty much any version of D&D or even many other games. 3rd Edition/Pathfinder players might lament the lack of Prestige Classes, but the Rune MAgic section can be easily converted to a Feat system. 5th Edition Players would need to work the Berserkers into a Barbarian sub-class/sub-type, but that would be easy enough.

It is not a perfect resource, but it is really close. I am really regretting selling off my physical copy now.

And here we are. The last of my regular features of One Man's God. I wanted to save the Norse for last because in many ways it was the myths of the Norse that showed me that there was a whole other world of myths and legends beyond the Greek. This happened, as it turned out, during a series of events that would lead me to D&D. In many ways the myths of the Norse are the most "D&D" of them all. The Monster Manual might be full of monsters of the Greek myths, the Norse myths run a very close second.

And here we are. The last of my regular features of One Man's God. I wanted to save the Norse for last because in many ways it was the myths of the Norse that showed me that there was a whole other world of myths and legends beyond the Greek. This happened, as it turned out, during a series of events that would lead me to D&D. In many ways the myths of the Norse are the most "D&D" of them all. The Monster Manual might be full of monsters of the Greek myths, the Norse myths run a very close second.The purpose though of One Man's God is to talk about demons. So let's get to it.

There are a lot of great entries for gods here and there are some really powerful monsters. But there isn't really anything here that says "demon" as D&D defines them. Or is there?

Among the creatures, we have the children of Loki, who here is listed as Chaotic Evil, who certainly could be considered demons. The Fenris Wolf is variously described as demonic and is Chaotic Evil. The same is true for Jormungandr. But they really don't fit the notion of demons. There is a type of creature from Norse Myth that does, the Jötunn.

Jötunar as Demons

There are a lot of good reasons to list the Jötunn as demons, even in the classical sense. The word Jötunn is often translated as "giant" or even "troll," but another translation is "devourer." This word is also the source of the word Ettin.

They are also described as predating the gods, coming from the primordial chaos, and the enemies of the gods. Sounds pretty demonic to me. It also sounds like the Titans of Greek myth, but more on that later.

The D&DG tells us that,

This lives on in the 4th Edition D&D mythology about Giants, Titans, and Primordials.

Jötunn, Inferno

Jötunn, InfernoThe progenitors of the Fire Giants, the Inferno Jötunn are a truly horrible sight to behold. They tower over the Storm Giants and rival the Titans in sheer size and strength. They are surrounded by flames and even their eyes, hair, and mouths are filled with flames. They are more violent than their cousins from Niflheim and Jötunheimr, the Rime Jötunn, but leave their lands much less often.

Inferno Jötunn all come from the land of Muspelheim, also known as Múspell which is also another name for these creatures. Muspelheim is a land of bright, white-hot flames that only these creatures and their fire giant offspring can withstand.

Inferno Jötunn are surrounded by flames that deal 2d6 hp of damage at all times. They wield great swords of flame and attack with their great strength (2d12+5) twice per round. Inferno Jötunn are immune to normal and magical fire including dragon breath. They have magic resistance at 55%. Rare individuals can also cast spells as a 9th level magic-user.

Their king is Sutur, also known as Surt. He commands his subjects with an iron fist.

Jötunn, Rime

Jötunn, RimeRime Jötunn are the primordial Frost Giants that first rose from Niflheim. Unlike the Inferno Jötunn, they range far and wide and are constantly battling with the Gods and other giants.

Rime Jötunn are surrounded by an aura of cold that deals 2d6 hp of damage at all times. They wield great swords of ice and attack with their great strength (2d12+6) twice per round. Rime Jötunn are immune to normal and magical cold including dragon breath. They have magic resistance at 55%. Rare individuals can also cast spells as a 9th level cleric.

These Jötunar can also adjust their size to appear as a human or elf as they need.

Niflheim is a cold, dark place of mists, ice, and gloom. Here the Rime Jötunn await with their lord Thrym to wage the final war on the gods in Ragnarök. Until they will cause as much evil as they can.

--

Rereading the Norse Myths you get the feeling that the Jötunar are more elemental in nature than even the fire and frost giants of D&D. Again in this respect, D&D 4th Edition had some great ideas.

While there are plenty of supernatural creatures in the lore of the Norsemen, with trolls and giants among the more popular, they are not represented in the D&DG and indeed mainly play a lesser role to the Gods and the dwarves of Norse myth.

And here are. The last of the regular entries for One Man's God. I have a few specials in mind to wrap up some ideas from this series and a "Norse Mythos, Part II" in a way later this week with a new "This Old Dragon." All in all, I am a little sorry to see it end. It has been a lot of fun.

Let's get back to this! A month off has made me a little rusty in my monster-making skills. Today's monster comes to me from a few sources. I spent my summer rereading a lot of my old psych textbooks and I decided to take a break and pick a bit of fluff about a guardian angel. I had no intention of doing anything with it, just a little a bit of enjoyable fluff.

Also, I am going to be spending a lot of time with some Norse myths and I wanted a creature today that I had not already done or seen a hundred times. The answer came to me in the form of the Hamingja.

Hamingja

HamingjaFrequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1)

Alignment: Lawful [Chaotic Good]

Movement: 120' (40') [12"]

Flying 180' (60') [18"]

Armor Class: 5 [14]

Hit Dice: 10d8+40**** (85 hp)

Attacks: 1 weapon (sword +1)

Damage: 1d8+3

Special: Astral projection, etherealness, fly, invisibility, luck, magic resistance 40%

Save: Fighter 10

Morale: 12 (NA)

Treasure Hoard Class: None

XP: 3,700 (OSE) 3,800 (LL)

Str: 16 (+2) Dex: 16 (+2) Con: 20 (+4) Int: 13 (+1) Wis: 14 (+2) Cha: 20 (+4)

Hamingja are akin to guardian angels. They appear as do valkyries, strong beautiful warrior women. But where the valkyries guardian the souls of the dead, the Hamingja are guardians of the living.

Each Hamingja exists to protect one family. They provide protection against supernatural and mundane attacks that target the family. They have an innate sense of which attacks are in need of their protection and which ones are not. So do not defend every attack, only ones that will ensure their charge does not die until their time as decreed by the Norns.

Unless they are needed the Hamingja will remain invisible. They will remain hidden in this way until they are needed. They typically act by increasing the ambient luck of their charges. Typically this translates to general +1 or +5% to any rolls their charges rolls. If their charge is attacked and the Norns have decreed this is when they will die the Hamingja will stay invisible until their charge is dead. They will then fly their soul to their appropriate place in the afterlife. They will then return to serve another member of the same family. If the Norns have not so decreed, then they will defend their charge with their swords.

The name Hamingja name means "happiness" or "joy" and their overall goal is to make the lives of their charges happier.

The gaming magazine is dead. After all, when was the last time that you were able to purchase a gaming magazine at your nearest newsagent? Games Workshop’s White Dwarf is of course the exception, but it has been over a decade since Dragon appeared in print. However, in more recent times, the hobby has found other means to bring the magazine format to the market. Digitally, of course, but publishers have also created their own in-house titles and sold them direct or through distribution. Another vehicle has been Kickstarter.com, which has allowed amateurs to write, create, fund, and publish titles of their own, much like the fanzines of Kickstarter’s ZineQuest. The resulting titles are not fanzines though, being longer, tackling broader subject matters, and more professional in terms of their layout and design.

—oOo— Published in January 2021—following a successful Kickstarter campaign by The Merry Mushmen—Knock! #1 An Adventure Gaming Bric-à-Brac promised and delivered some eighty-two entries contributed by some of the most influential writers, publishers, and commentators from the Old School Renaissance, including Paolo Greco, Arnold K, Gabor Lux, Bryce Lynch, Fiona Maeve Geist, Chris McDowall, Ben Milton, Gavin Norman, and Daniel Sell, along with artists such as Dyson Logos and Luka Rejec. From the off, it grabbed the reader’s attention and began giving him stuff, including a dungeon adventure on the inside of the dust jacket! Inside its pages contained a panoply of articles and entries—polemics and treatises, ideas and suggestions, rules and rules, treasures, maps and monsters, adventures and Classes, and random tables and tables, followed by random tables in random tables! All of which is jam-packed into a vibrant-looking book. All primarily written for use with Necrotic Gnome’s Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy, but readily and easily adapted to the retroclone of the Game Master’s choice, and laid out out with a graphic style which was heavily influenced by the look (though not the tone) of Mörk Borg to eye-catching and distinctive effect.

Published in January 2021—following a successful Kickstarter campaign by The Merry Mushmen—Knock! #1 An Adventure Gaming Bric-à-Brac promised and delivered some eighty-two entries contributed by some of the most influential writers, publishers, and commentators from the Old School Renaissance, including Paolo Greco, Arnold K, Gabor Lux, Bryce Lynch, Fiona Maeve Geist, Chris McDowall, Ben Milton, Gavin Norman, and Daniel Sell, along with artists such as Dyson Logos and Luka Rejec. From the off, it grabbed the reader’s attention and began giving him stuff, including a dungeon adventure on the inside of the dust jacket! Inside its pages contained a panoply of articles and entries—polemics and treatises, ideas and suggestions, rules and rules, treasures, maps and monsters, adventures and Classes, and random tables and tables, followed by random tables in random tables! All of which is jam-packed into a vibrant-looking book. All primarily written for use with Necrotic Gnome’s Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy, but readily and easily adapted to the retroclone of the Game Master’s choice, and laid out out with a graphic style which was heavily influenced by the look (though not the tone) of Mörk Borg to eye-catching and distinctive effect.This illustration is reproduced in the tribute collection The Fantastic Art of Clark Ashton Smith by Dennis Rickard (Mirage Press, 1973).

If you are interested in owning this original Clark Ashton Smith drawing, it is currently available through the Heritage Auctions website. It is attached to an auction in early October. The full page with all related information at the Heritage Auction website can be viewed here.

I previously shared the art of Clark Ashton Smith in 2006 with a thumbnail of this artwork here.

The gaming magazine is dead. After all, when was the last time that you were able to purchase a gaming magazine at your nearest newsagent? Games Workshop’s White Dwarf is of course the exception, but it has been over a decade since Dragon appeared in print. However, in more recent times, the hobby has found other means to bring the magazine format to the market. Digitally, of course, but publishers have also created their own in-house titles and sold them direct or through distribution. Another vehicle has been Kickststarter.com, which has allowed amateurs to write, create, fund, and publish titles of their own, much like the fanzines of Kickstarter’s ZineQuest. The resulting titles are not fanzines though, being longer, tackling broader subject matters, and more professional in terms of their layout and design.

—oOo— Published in June, 2020, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition proved to be both a disappointment and enjoyable. It promised to be, “The monthly magazine of RPGs, Tabletop Games, Comic Conventions, Art Reviews, Adventures & More! In this prodigious premiere issue, you will find adventure hooks for roleplaying games, RPG dice tables, reviews, artist and game designer interviews, original art, tips, tricks, NPCs, treasure and maps.” It was an ambitious claim, and it very much made it sound like a gaming magazine. It was not, and that was the disappointing bit. The problem is was that its focus initially and in the main was on the ‘More’ of that subtitle—books, films, computer games, and so on rather than games. This is not to say that there was no roleplaying content to be found in its pages. There was, and it was decent too. Kristopher McClanahan’s systemless, Lovecraftian ode to Pulp Sci-Fi roleplaying games, ‘Realm of the Moon Ghouls Part 1: The Starship Poe’ was fun, and ‘H’AKKENSLASH! An original RPG system’ by Benjamin C. Bailey showed promised. Thus once you accepted that Tabletops and Tentacles #1 was not a gaming magazine, but a general fandom magazine with the gaming content saved for the issue’s back half, it proved to be an enjoyable read.

Published in June, 2020, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition proved to be both a disappointment and enjoyable. It promised to be, “The monthly magazine of RPGs, Tabletop Games, Comic Conventions, Art Reviews, Adventures & More! In this prodigious premiere issue, you will find adventure hooks for roleplaying games, RPG dice tables, reviews, artist and game designer interviews, original art, tips, tricks, NPCs, treasure and maps.” It was an ambitious claim, and it very much made it sound like a gaming magazine. It was not, and that was the disappointing bit. The problem is was that its focus initially and in the main was on the ‘More’ of that subtitle—books, films, computer games, and so on rather than games. This is not to say that there was no roleplaying content to be found in its pages. There was, and it was decent too. Kristopher McClanahan’s systemless, Lovecraftian ode to Pulp Sci-Fi roleplaying games, ‘Realm of the Moon Ghouls Part 1: The Starship Poe’ was fun, and ‘H’AKKENSLASH! An original RPG system’ by Benjamin C. Bailey showed promised. Thus once you accepted that Tabletops and Tentacles #1 was not a gaming magazine, but a general fandom magazine with the gaming content saved for the issue’s back half, it proved to be an enjoyable read.Tabletops and Tentacles #2 – The Quarantine Issue follows the same format, but it is a much queerer beast, for this is the issue written during and in response to the year in lockdown that was 2020. Published in January, 2021 by Deeply Dapper Games, the issue offers up the usual mix of columns, features, and interviews, covering films—lots of films, reviews, and more, all coloured by the fact that its contributors had to stay at home and not go anywhere. That starts with Kris McClanahan’s editorial ‘Notes from the Depths’, in which he laments the change in circumstances forced upon him and his partner by the pandemic. That is no criticism, for we have all had to do it and adapt as best we can, but he is more used to travelling and presenting at one convention after another. There can be no doubt that Covid-19 has changed many lives and the way we live, and its spread is the closest that we have come to an apocalypse—yet. How we survived and what we did is reflected in the issue, which focuses on plagues, apocalypses, pandemics, and the like across our media. This is very much reflected in the issue’s first half, which does feel as if can be summed up as ‘What I watched in quarantine’. The issue’s reviews—the previews having been dropped due to the difficulty of their being relevant—cover a mix of the old and the new, including a lot of crime such as S.A. Cosby’s Blacktop Wasteland and Michael Connelly’s Fair Warning. The fantastic includes Peace Talks, the latest Harry Dresden from Jim Butcher, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, and the graphic novel, The Adventure Zone Vol. 1: Here There Be Gerblins by The McElroys & Carey Pietsch. The ‘Spotlight’ on The Andromeda Strain is sadly all too short in comparison to the reviews of Netflix series like Warrior Nun and Amazon Prime films such as Blow the Man Down. Video game reviews include the excellent The Outer Worlds, Griftlands and Earth Defense Force 5, plus tabletop reviews which cover Sandy Petersen’s Cthulhu Mythos and the first part of the adventure quartet, Yig Snake Granddaddy: Act 1: A Land Out Of Time. In general, it is a good mix of reviews, the familiar with the unfamiliar.

In ‘Thoom! Theater’ Thom Chiaramonte presents his fantasy cast for The Fantastic Four. This is an interesting take upon the classic Marvel superhero group, more interesting than the previous filmic takes, including detailed casting suggestions and a complete story outline. With an origin shifted forward to the nineteen seventies rather than the nineteen sixties, this is all very speculative, but given the recent release of the series, What If! for the Marvel Cinematic Universe, it does not read as being, well, too fantastic.

Less useful and less interesting—at least for a non-American readership—is Kris McClanahan’s ‘Islands in the Stream: The Tabletops & Tentacles Guide To Streaming Channels’, which does what it says on the tin. An eleven-page guide and opinion to every television and film streaming service imaginable. Many of these are available outside of the USA, but then just how many such services do you need, or indeed, have time to watch? The counterpoint to this guide is his ‘In Praise of Physical Media’, which highlights the advantages of checking your library of DVDs you have been avoiding with all of that ready access to instant video on demand. Better quality, limited choice (really!), and of course, the extras. It would have been interesting to find out a little bit as to what he pulled off the shelf, but otherwise definitely a better read than the streaming guide.

Also a better read is the editor’s second entry in the regular column, ‘50 Films You DON’T Need To See’. In Tabletops and Tentacles #1, it was Toy Story. In Tabletops and Tentacles #2, it is Night of the Living Dead, and as before, this is an examination of the film, warts and all. It is better for it, because despite it being a cliché in places (but then it was the original and set those clichés!), some odd shots, limited budget, and the then inexperience of George A. Romero, it is still very much a classic zombie and classic horror film. This is an enjoyable re-examination of the film, and it is very much s pity that The Andromeda Strain did not receive a similar—though not exact—treatment earlier, as given its age and subject matter, it would have been very appropriate for the issue.

Both the ‘What I watched in quarantine’ and the plague themes continue with ‘The Binge’ in which the editor takes advantage of one streaming service after another to dive down a rabbit hole of one bad apocalyptic film followed by probably worse bad apocalyptic film… If the article is not worth reading for the films—and the likelihood is that the reader really has to like bad films for it to be seen as a guide to bad film—then there is recompense in the author’s self-flagellation in making himself endure the four films he watches here. The theme is carried on in ‘The Top ten Pop Culture Pandemics!’ which draws roleplaying games, television, film, comic books, novels, and video games, and as lists go, the plenty to agree and disagree with. That said, Wild Card virus from the series of the same name edited by George R.R. Martin should definitely have been on the list.

Devon Marcel offers his own suggestions within the issue’s themes with ‘That’s Quarantainment! – Quarantine themed media for life during lockdown’, and what he viewed and read and played. Just three titles are examined, but space enough is given to each to make them sound interesting and worth tracking down. The three are the Val Lewton directed, Boris Karloff starring Isle of the Dead, of which Marcel is highly positive; Frozen Hell, an earlier iteration of 1938 short story ‘Who Goes There?’ by John W. Campbell, Jr., which would form the basis for both versions The Thing From Another World, of which the author find interesting as a curiosity, but little more; and The Bunker, a Full Motion Video adventure game from Splendy Games, a horror game set entirely in an underground bunker which he thoroughly enjoyed. Again, the article is the all the better for the space it is given, and each of the three items covered is more interesting for it also.

‘Quest Accepted: My Epic Adventure Into VR’ by Shawn Lance takes us on the author’s introduction to playing on the Occulus Quest. It is a serviceable read, but could have been improved with illustrations of the games he played, otherwise, it feels divorced from his experience.

The issue makes a very noticeable switch to fiction to ‘The Book Club’. In a similar fashion to the earlier ‘50 Films You DON’T Need To See’, this examines H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘The Festival’, one of his minor short stories and breaks down its plot, history, what he liked and disliked, along with his final thoughts, trivia, and more, and again is an enjoyable appreciation. Two actual pieces of fiction follow. The first is the second part of ‘Sowing Dragon Teeth’, a fantasy story with pulpy tones by James Alderdice, which continues to be as enjoyable as the first part in Tabletops and Tentacles #1, whilst the second is Neal Kristopher’s ‘No More Masks’, a post-apocalyptic tale that is very much a commentary on the decision whether or not to wear a mask in the least or so, and going forward.

The actual gaming content in Tabletops and Tentacles #2—some eighty pages in—begins with a pair of interviews. The first is with Cullen Bunn, author of the Dungeons & Dragons-inspired Deepest Catacombs. Based on the old-school adverts from TSR, Inc. for the game from the seventies and eighties, this does a nice job selling the concept, especially with the samples from Bunn’s current project and the inspiration for it. The other interview is ‘Gaming from the Hearth’ which is with the husband-and-wife team behind Fireside Games, the publisher of Castle Panic. Conducted just prior to the beginning the lockdown, the couple talk about how they work and the challenges of bringing any game, let alone a deluxe version of Castle Panic to the market, and it is concluded with postscript four months on, looking at the state of the company and the industry deep into the effects of the pandemic. In a way, it bookends Kris McClanahan’s editorial ‘Notes from the Depths’, in which he laments the change in circumstances forced upon him, his partner, and their business by the pandemic. It is a change which many businesses have suffered sadly, and the difficulties of operating under the pandemic cannot be underestimated.

Alan Bahr’s regular column, ‘Tiny Thoughts’ showcases just a handful of the post-apocalyptic roleplaying games available. It mentions—and they are tiny mentions—Punkapocalyptic, Apocalypse World, Pugmire, and more, but does suggest ways of roleplaying under the pandemic as so many have, using Roll20, Fantasy Grounds, and so on. This is the only mention of such methods in the issue and the truth of the matter is that Tabletops and Tentacles #2 – The Quarantine Issue misses this trick—and when it comes to lockdown and gaming, it is a very important trick. So many have adapted to roleplaying online rather than face-to-face, including at virtual versions of major conventions, and it is shame that barring this mention, the issue ignores it.

The first of the actual gaming content in Tabletops and Tentacles #2 comes some hundred or so pages into the issue. Kristopher McClanahan and Lindsay McClanahan continue the gaming dice tables for ‘In the Inn’ with twenty things to be found on a shelf in a cellar in the inn, whilst ‘Symptoms of the Sickness’ by Lindsay McClanahan provides random symptoms exactly as its title promises. The longer gaming content starts with ‘The Green Infection’, a systemless fantasy scenario in which the village of Ainsmoor has been beset by a deadly pandemic of its own. It is fairly straightforward, but nicely detailed, and easily adapted to the system—and even setting—of the Game Master’s choice. it is followed by ‘Realm of the Moon Ghouls File 02: Location Shuttle Station Sixteen’ which further details the Lovecraftian setting for Pulp Sci-Fi roleplaying games. This details a space station suitable for the crew of the Poe to refuel with Strontium. It is a fun little setting complete with half-alien, half-robot cook, space pirates, and a handful of story hooks. Unfortunately, it is let down by the news that future installments of ‘Realm of the Moon Ghouls’ is moving to Patreon. It is disappointing that the most enjoyable content in the issue will not be is easily available.

The expansion for ‘H’AKKENSLASH! An original RPG system’ by Benjamin C. Bailey presents ‘Monsters and Mayhem’, a set of ten new monster abilities for the Game Master, such as Vampirism, Quick, and Combustible. These are decent additions. Rounding out the issue is a further entry in ‘Merchants of the Realm’. ‘Merchants of the Realm: Millhaven Curiosities’ by Kris McClanahan. This describes a mysterious alleyway shop, small and full of strange shadows, its proprietor simply watching... unless engaged in which case he will be a font of knowledge, rumour, and even adventure hooks! Here the adventurers might be able to buy a Webbing Scroll, a surly vampire bat in a cage, Mr. Pointy, a slightly off-kilter stake stained in ash and blood—and those are only some of the interesting items crammed into the premises. ‘Merchants of the Realm: Millhaven Curiosities’ is likeable and servicable, easy to add to any fantasy campaign, whether medieval or modern.

Physically, Tabletops and Tentacles #2 is generally well-presented, being bright and cheerful. It seems an improvement over the previous issue, there being less of an effort to pack quite so much in. Again, the editing could have been stronger, but hopefully that will get better with future issues.

After having read Tabletops and Tentacles #1, coming to Tabletops and Tentacles #2 – The Quarantine Issue is very much less of a disappointment because the reader knows what to expect, that it is not a gaming magazine so much as general fandom magazine. It suffers from that lack of gaming specificity in terms of actual gaming found in other magazines, and gaming wise, it could have leaned harder into the apocalyptic theme. There still is not enough gaming content to wholly recommend Tabletops and Tentacles #2 – The Quarantine Issue as a gaming magazine, but as a general fandom magazine with some gaming content, it is an enjoyable read.

It's been a bit for this. I thought with the Night Companion Kickstarter in its last few hours a NIGHT SHIFT version of Zatanna is in order.

Zee is obviously very powerful in DC Comics, or to quote Felix Faust, "You're the only one here that's really a threat." Bear in mind the others in the room were John Constantine, Etrigan the Demon, Deadman, and Batman.

How would she fare in Night Shift? For starters, I am going to shift her prime from Wisdom (for witches) to Intelligence. In fact, I borrow a rule from my co-author's, Jason Vey, other game Amazing Adventures, and allow my witches to take whichever mental stat they need for their Primary/Spellcasting.

In the comics, we Zee practicing, sometimes with flashcards even, how to say words backward. It takes her practice to learn and do. That is more aligned with the old-school D&D magic-user really than a witch and that means Intelligence.

Zatanna made with HeroForgeZatanna Zatara

Zatanna made with HeroForgeZatanna ZataraBase Abilities

Strength: 13 (+1)

Dexterity: 13 (+1)

Constitution: 16 (+2)

Intelligence: 20 (+4) P

Wisdom: 16 (+2) s

Charisma: 18 (+3) s

HP: 83 (10d4+18) +40

AC: 5 (stage magician's outfit, with benefits)

Fate Points: 1d10

Check Bonus (P/S/T): +8/+5/+3

Melee bonus: +7 Ranged bonus: +7

Saves: +8 against spells and magical effects

Arcana: Command, Telepathic Transmission

Innate Magic: Magical Missile,

Hair: Black

Eyes: Blue

Spells

1st level: Command, Cure Light Wounds, Detect Magic, Inflict Light Wounds, Magic Missile, Protection from Evil

2nd level: Cause Fear, Continual Flame, Lesser Restoration, Levitate, Suggestion

3rd level: Clairvoyance, Fly, Haste, Invisibility 10', Protection from Evil 10'

4th level: Arcane Eye, Confusion, Dimension Door, Hallucinatory Terrain, Restoration.

5th level: Commune, Domination, Telekinesis, Teleport

6th level: Anti-magic Shell, Control Weather, Disintegrate, Feeblemind

7th level: Ball of Sunshine, Death Aura, Wave of Mutilation, Windershins Dance

8th level: Antipathy/Sympathy, Discern Location, Mind Blank, Wail of the Banshee

9th level: Astral Projection, Breath of the Goddess, Mystic Barrier

Even at 20th level, she is still not super powerful. Oh, she will kick your ass, but you might still get a hit or two in.

--

Want more? Back the Night Companion on Kickstarter!

The gaming magazine is dead. After all, when was the last time that you were able to purchase a gaming magazine at your nearest newsagent? Games Workshop’s White Dwarf is of course the exception, but it has been over a decade since Dragon appeared in print. However, in more recent times, the hobby has found other means to bring the magazine format to the market. Digitally, of course, but publishers have also created their own in-house titles and sold them direct or through distribution. Another vehicle has been Kickstarter.com, which has allowed amateurs to write, create, fund, and publish titles of their own, much like the fanzines of Kickstarter’s ZineQuest. The resulting titles are not fanzines though, being longer, tackling broader subject matters, and more professional in terms of their layout and design.

—oOo— Parallel Worlds feels a little old-fashioned. By which Reviews from R’lyeh means that it supports the gaming hobby with content for a variety of games. So an issue might include new monsters, spells, treasures, reviews of newly released titles, scenarios, discussions of how to play, painting guides, and the like… That is how it has been all the way back to the earliest days of The Dragon and White Dwarf magazines. By which Reviews from R’lyeh means that it can be purchased, if not from your local newsagent, then from your local games store. Just like The Dragon and White Dwarf magazines could be back in the day. However, Parallel Worlds, published by Parallel Publishing can also be purchased in digital format, because it is very much not back in the day.

Parallel Worlds feels a little old-fashioned. By which Reviews from R’lyeh means that it supports the gaming hobby with content for a variety of games. So an issue might include new monsters, spells, treasures, reviews of newly released titles, scenarios, discussions of how to play, painting guides, and the like… That is how it has been all the way back to the earliest days of The Dragon and White Dwarf magazines. By which Reviews from R’lyeh means that it can be purchased, if not from your local newsagent, then from your local games store. Just like The Dragon and White Dwarf magazines could be back in the day. However, Parallel Worlds, published by Parallel Publishing can also be purchased in digital format, because it is very much not back in the day.

Time to come back to Friday Night Videos!

With NIGHT SHIFT Night Companion Kickstarter ending soon I thought IT would be good to celebrate the return of cooler nights.

Let's get some night music going.

Up first, the song that really should be the theme song for NIGHT SHIFT,

The Police's Bring on the Night.

NIGHT SHIFT is old-school mechanics with a new-school attitude. D&D meets Modern Supernatural. So no one genre of music is going to cover this giant peanut butter cup of awesome.

So here is Onyx and Biohazard on Judgement Night.

One day I should stat up Gibby Haynes as a NIGHT SHIFT character. He'd fit in perfectly.

And we all know Stevie Nicks would.

How could I forget our lovely immortal?

And the song my kids sing when we all play. The NIGHT. BEGINS. TO SHINE!

Enjoy the night!

Night Companion is nearing the end of the Kickstarter! Join us.

LAST BIG PUSH!!

This sourcebook for Night Shift: VSW RPG blows the doors off! New classes, species, magic, monsters, core system options, and more.

Night Shift has been a labor of love for Jason Vey and I. It has been a chance to use the rules we love (Old-school D&D) and bring it to a modern supernatural setting like the licensed products we have worked on in the past. If you liked any of my work regardless of the system used then this is a great fit.

Here is what the book is right now:

The gaming magazine is dead. After all, when was the last time that you were able to purchase a gaming magazine at your nearest newsagent? Games Workshop’s White Dwarf is of course the exception, but it has been over a decade since Dragon appeared in print. However, in more recent times, the hobby has found other means to bring the magazine format to the market. Digitally, of course, but publishers have also created their own in-house titles and sold them direct or through distribution. Another vehicle has been Kickststarter.com, which has allowed amateurs to write, create, fund, and publish titles of their own, much like the fanzines of Kickstarter’s ZineQuest. The resulting titles are not fanzines though, being longer, tackling broader subject matters, and more professional in terms of their layout and design.

—oOo— Senet—named for the Ancient Egyptian board game, Senet—is a print magazine about the craft, creativity, and community of board gaming. It is about the play and the experience of board games, it is about the creative thoughts and processes which go into each and every board game, and it is about board games as both artistry and art form. Published by Senet Magazine Limited, each issue promises previews of forthcoming, interesting titles, features which explore how and why we play, interviews with those involved in the process of creating a game, and reviews of the latest and most interesting releases.

Senet—named for the Ancient Egyptian board game, Senet—is a print magazine about the craft, creativity, and community of board gaming. It is about the play and the experience of board games, it is about the creative thoughts and processes which go into each and every board game, and it is about board games as both artistry and art form. Published by Senet Magazine Limited, each issue promises previews of forthcoming, interesting titles, features which explore how and why we play, interviews with those involved in the process of creating a game, and reviews of the latest and most interesting releases.Senet Issue 1 was published in the Spring of 2020 and carries the tagline of “Board games are beautiful”. It opens with ‘Behold’, a preview of some of the then-forthcoming board game titles, such as Oathsworn: Into the Deep Woods, Oceans, and Oath: Chronicles of Empire and Exile. Given as much prominence as a full review, what is interesting about these is previews is that each give ‘What they might be’, so Oath: Chronicles of Empire and Exile might be the new Civilization, Sub Terra II: Inferno’s Edge the new Escape: The Curse of the Temple, and so on. Many, if not all, of these titles have since been released and been subject to their own reviews and analysis, so these previews can be read with the benefit of hindsight to see whether their predictions were right.

‘Points’ provides a selection of readers’ letters, whilst in ‘For Love of the Game’, Tristian Hall begins his designer’s journey towards Gloom of Kilforth. Here he talks about the genesis of the idea behind the board game and its inspirations, laying the groundwork for the process to come. This should be a fascinating path to follow in future columns.

Thematically, Senet Issue 1 pursues a pair of the board gaming industry’s most recent trends—Mars and Vikings. In ‘Out of the World’, board game visualist Ian O’Toole shows how he developed the look and visual style of On Mars. It mentions other titles he has worked on, but in the main, the article takes the visual and graphical development of On Mars from start to finish, showing the various stages through which O’Toole takes his design. It is a genuinely fascinating journey which throws the spotlight on someone involved other than a designer. The other theme is Vikings and board games journalist, Owen Duffy, looks at several of the high-profile Viking-themed board games which have been released over the last few years in ‘Vahalla Rising’. It notes our fascination with the Vikings, but makes the point that there is more to them than raiding and pillaging, which as much as raiding and pillaging is often part of Viking-themed board games, there are an increasing number of designs where that is not the case. For example, Shipwrights of the North Sea is about shipbuilding. The article points out that this may be just another thematic cycle, but perhaps not given our long association with Viking history and the fact that they too, played board games.

Similarly, two common mechanics are examined in the issue. With ‘Work Hard Place Hard’, Matt Thrower investigates the worker placement mechanic, which proved very popular in the late noughties and early tweenies, fostering competition without confrontation. It traces its origins back to a game called Keydom from 1998. Notable examples—Agricola, Caylus, and Le Havre, amongst others—are used as examples, and the examination looks at variations which use dice, involve time, and provide a sense of progress. Lastly, it looks forward to the future of the mechanic and then-forthcoming titles using it. There are numerous examples it misses of course, likely one of the reader’s favourites, but it is a case of hitting the notable examples. The other mechanic—or is that style of play—is the co-operative game. Alexandra Sonechkina writes the first ‘How to Play’ column which is entitled ‘Cooperative games can make us better people’, which provides a short history of the genre, emphasising that the removal of competition between players not only removes conflict, but leads to stronger shared experience.

The longest piece in Senet Issue 1 is ‘High Flyer’, an in-depth interview with Elizabeth Hargrave, the designer of the 2019 Kennerspiel des Jahres winning Wingspan. This an interesting and informative piece, designer answering honestly about the challenges of being a female designer in the industry as much as her design process and the themes which attract her, which as Wingspan and her then-latest design, Tussie Mussie, are far from the traditional castles and similar elements. Hopefully, future issues will have interviews as nicely done and enjoyable as this one is.

No good gaming magazine would be without games reviews, and Senet Issue 1 is no exception. Just the ten, but all regarded as the magazine’s ten favourites from the year before, that is, 2019. Rounding out Senet Issue 1 is ‘Shelf of Shame’ in which a prominent gamer is asked to play a game that he has on his shelf, but never played. In this first column, the gamer is Paul Grogan of Gaming Rules! and the game is 1999’s Torres, also the 2000 Spiel des Jahres Winner. One obvious reason why he has not played this despite having a copy is the ‘cult of the new’, but he is not necessarily correct about a reviewer always getting more views for something that is ‘hot and new’. Retrospectives can generate plenty of views. The column feels less about the game and more about the fact that he has not played it, but is interesting enough. His very first play through of the game can be seen here.

Physically, Senet Issue 1 is very nicely presented, all pristine and beautifully laid out. Whether drawing on board game graphics and images, or the magazine’s own illustrations, the issue’s graphics are very sharply handled, living up to the issue’s motto of “Board games are beautiful” as much as its subject matter does.

Senet Issue 1 is a very impressive first issue and can be enjoyed whether you are relatively new to the hobby or a long-time participant. It sets out to inform and illustrate, and in doing so—sets a high standard for the issues to come.

The Battle Between Good and Evil

The Battle Between Good and Evil

Ellen in Wonderland 3 - The visit to the forest with the human worms

Ellen in Wonderland 3 - The visit to the forest with the human worms

Ellen in Wonderland 2 - Ellen in dispute with a little harlequin

Ellen in Wonderland 2 - Ellen in dispute with a little harlequin

The Bummer - Odysseus at Kirke

The Bummer - Odysseus at Kirke

I made the impossible come true

I made the impossible come true

What do you think about marriage?

What do you think about marriage?

Study for - The Liberation of Andromeda

Study for - The Liberation of Andromeda

A Painful Encounter Artworks found at

A Painful Encounter Artworks found at

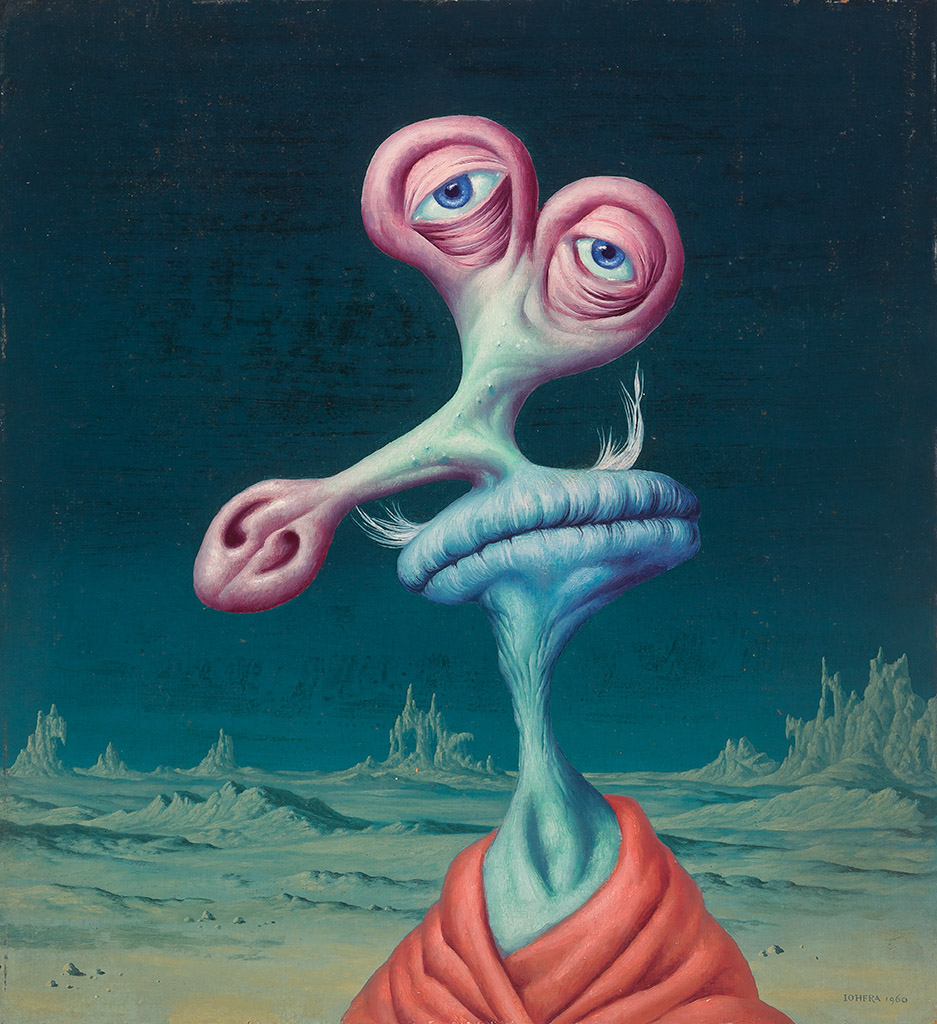

Artworks found at the Pathos Gallery website. A large retrospective of artworks by Johfra Bosschart will be on display starting September 21st at the Pathos Gallery in Amsterdam.

"Pathos Gallery presents: Johfra Bosschart

A selection of works by the Dutch godfather and pioneer of surrealism and fantastic realism.

Born as Franciscus Johannes Gijsbertus van den Berg, he later in 1945 adopted the pseudonym JohFra by using the first three letters from each of his two first names in reverse order. Much of his early life was spend in The Hague. From an early age he showed great abilities in drawing and later attended lessons at the Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague.

By 1943 he had assembled a considerable body of work that he was able to mount an exhibition. Most of his early pieces were destroyed in a bombing raid during the closing years of the Second World War. One that survived is his Fantastic figure of 1942.

In German occupied Holland he had little access to the wider art world but he did obtain a Nazi propaganda magazine with an article about degenerate art. This introduced him to the imagery of Dalí, Ernst, Tanguy, and Magritte. He became especially drawn to the work of Dalí. After the war Johra was free to paint and he produced a profusion of work. His Terra Incognita of 1955 clearly demonstrated the influence of Dalí. Throughout the 1950s he created many paintings in a flowing organic style.

In 1959 Johfra travelled to Port Lligat with the intention of meeting Salvador Dalí. Their meetings were somewhat strained and strange, but Dalí took them to his studio where he showed Johfra The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus which he was then working on. Johfra, however, was rather disappointed with Dalí as he wrote in his diary "This visit left a storm of conflicting thoughts and feelings behind us. I found him repulsive yet sympathetic and tragic. An imprisoned person who is forced to be the figure that he himself has created. A victim of a world in which he is the fool, and of himself through his boundless vanity, making him impossible to break out of this situation. What I missed completely was every trace of joy and humour."

In the immediate post war years Johfra became involved with a fellow Dutch artist Diana Vanbenberg and they married in 1952. They were able to travel to Rome. Johfra held several solo exhibitions and gained some degree of financial stability. The 1950s saw the development of his mature surrealist style.

In A Spring Morning of 1957 he began to develop the tangled organic landscapes which appear in many of his later paintings. In 1967 he produced a series of four drawings on the theme of schizophrenia. Perhaps these show some influence from the symbolic language of Hieronymous Bosch and Breughel. These drawings marked a departure from his earlier surrealistic style towards a more emblematic, instructive and didactic one. This was perhaps already a component of his work, as is seen in the emblematic Son of the Snakes of 1951, but now this pictorial form became more central and his surrealist style somewhat diminishes in importance for him.

This perhaps reflects the influence of a new artistic partner in his life Ellen Lórien, whom he married in 1973. The 1970s marked an amazingly fruitful period for Johfra with the creation of many of his major pieces. It was during this period that art historian Hein Steehouwer devised the term 'Meta-Realists' for Johfra and the other artists in his circle suggesting they were depicting a realm beyond, or standing above, the real.

This was followed a year later by his Zodiac series which immediately touched the popular imagination as it appeared as illustrations in various books, and was made into large wall posters popular among the new age enthusiasts. Johfra later found this series to be a considerable burden as this became so bound to his name that his other work was unfortunately ignored. He described his works as "Surrealism based on studies of psychology, religion, the bible, astrology, antiquity, magic, witchcraft, mythology and occultism."

Johfra's legacy has been rather affected by the popularity of his 1970s Zodiac series, so much so that many of his surreal works became marginalised, however, we should view him as a significant surrealist, who shifted into a more emblematic, narrative and didactic style, in what was labelled as meta-realist, a term which he later disowned." - quote source

Johfra was previously shared on Monster Brains in 2009 and 2006.