Outsiders & Others

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Unnamable (1988)

I started watching 1988's The Unnamable tonight thinking for sure I had seen it. Started it, couldn't remember it, then realized I had seen it.

I started watching 1988's The Unnamable tonight thinking for sure I had seen it. Started it, couldn't remember it, then realized I had seen it.The Unnamable (1988)

So there must be an unwritten rule that all modern adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft must take place in or around Miskatonic University and/or Arkham. After all, it makes good sense and if I were a filmmaker it is what I would do as well. Of course, it doesn't mean you always have to do it.

Case in point there is almost more about M.U. here than there is about the titular monster/character here. We get glimpses into the undergraduate life, the student body (and bodies), even people majoring in things other than medicine and the dark arts. But all of this is just fluff for the main story. Again a common problem, how to make a full-length movie out of a short story.

This one features Lovecraft's reoccurring protagonist Randolph Carter (this time played by Mark Kinsey Stephenson).

It is typical late 80s fare. Lots of gore. Lots of implied sexual antics.

In this second viewing (or third, who knows) I can help but think Randolph Carter here is kind of a jerk. By the time he comes around to helping anyone half the cast is dead. Yeah, it's a horror flick people are going to die, but his laissez-faire attitude borders on sociopathic negligence rather than a cool distance.

I wanted to also watch The Unnamable II but I can't find it anywhere. This is also a problem I am having with other Lovecraft-based flicks.

October 2021

Viewed: 11

First Time Views: 4.5

The Golden Hydra: King Ghidorah, Astro-Colonizers, and Cold War Empire

Alex Adams / October 6, 2021

In Toho’s 1965 tokusatsu spectacular Invasion of the Astro Monster, humanity makes contact with ruthless hive-mind aliens from Planet X, a new stellar body discovered on the far side of Jupiter. The aliens who inhabit this cold, bleak planet—the Xiliens—are a technologically advanced but blankly unemotional civilization, a race of grey-clad scientists whose remarkable intellectual development has allowed them to live safely underground in the hostile, unwelcoming environment of Planet X. They propose an interplanetary trade: if the world’s authorities—Japan, the US, and the UN—will lend them Godzilla and the fire-hawk Rodan in order to fight off the murderous three-headed space dragon King Ghidorah, who has, of late, become the scourge of Planet X, the Xiliens will provide humanity with the cure for cancer. This trade sounds like a win-win, a blessing, as Earth will simultaneously be rid of its two most troublesome inhabitants and gain a medical miracle. But, of course, it is a cynical double-cross: by stealing Godzilla and Rodan, the Xiliens have captured Earth’s only defences against Ghidorah, who is in fact a living weapon under their control that they plan to use to colonize Earth. Though the “superior” race comes offering gifts, they in fact seek to subjugate and exploit.

Invasion of the Astro Monster is a potent blend of alien invasion, mind control, and interplanetary blackmail. This story, retold several times in the Shōwa era of the Godzilla franchise, is a clear engagement with themes of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism that were very much current across the globe in the mid-1960s, a decade featuring a panoply of gruesome colonial wars the world over in Algeria, Vietnam, Angola, Kenya, and elsewhere. It is widely acknowledged that Godzilla is, as Ian Buruma writes in the BFI DVD booklet for Ishiro Honda’s original Godzilla (1954), “a profoundly political monster.” But Godzilla’s many sequels are often written off as cheap and goofy cash-ins. Big mistake. Much as US sci-fi movies like The Blob (1958), The Thing From Another World (1951) or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) used alien encounters to think through themes of cross-cultural contact, colonialism, and communism, the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are a rich engagement with world-historical themes of Cold War antagonism, first contact, and imperial manipulation.

A History of the DragonGodzilla has long been understood as a powerful symbol of nuclear devastation and the horror of war. While this is true, Godzilla has taken many forms over his seventy-year career, and he has symbolized a great many things. Philip Brophy writes that Godzilla is “less a vessel for consistent authorial and thematic meaning as he is a shell to be used for the generation of potential and variable meanings.” This is true of many of his adversaries too. Monsters have always been tremendously flexible and evocative ways of digesting ideas, fears, and emotions, and Toho’s Kaiju are no exception.

King Ghidorah, an enormous three-headed golden dragon inspired by Yamata No Orochi—a fearsome eight-headed dragon from Shinto mythology—is perhaps Godzilla’s most frequently battled adversary. Along with Mechagodzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and Godzilla, King Ghidorah is one of the cornerstones of the Kaiju Big Five, and his antagonism with Godzilla headlines eight movies, with further variations on Ghidorah also appearing in Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) and the Heisei Mothra trilogy (1996-1998). In the Shōwa period (1954-1975), he is a villain in Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster (1964), its sequel Invasion of the Astro Monster, the blockbuster monster brawl Destroy All Monsters (1968), and, as a supporting character, in Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972). In the Heisei period (1984-1995), Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991) would see Ghidorah inflicted on Japan by time-travelling saboteurs—not to mention his cyborgic resurrection as Mecha-King-Ghidorah at the film’s climax. Ten years later, Ghidorah’s role was reversed when he teamed up with Mothra and Baragon to save humanity from Godzilla in Shusuke Kaneko’s Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001). Later in the twenty-first century, King Ghidorah once again features as Godzilla’s arch-nemesis in The Planet Eater (2018), the climactic movie of the Polygon Anime trilogy, and King of the Monsters (2019), the second movie in the ongoing Legendary MonsterVerse. No other monster confronts Godzilla so many times and in so many forms. His Cold War appearances are, thematically, particularly rich and rewarding.

King Ghidorah’s first movie, Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster, is a crossover sequel that, through its incorporation of other successful Toho monsters into the Godzilla franchise, was the Avengers: Endgame (2019) of its day. In Rodan (1957), aggressive mining operations awaken a species of enormous and destructive prehistoric birds, and in Mothra (1961) a scientific expedition to Infant Island incurs the wrath of a colossal and beautiful winged insect. Both of these monsters would return in Ghidorah, meshing together their continuities with Godzilla’s and building a wider fictional universe overflowing with Kaiju. Both Rodan and Mothra had a clear environmentalist emphasis, but Mothra is particularly explicit with its political themes. Through its characterization of the greasy capitalist Clark Nelson as an amoral and exploitative villain and its satire of the imperialist nation “Rolisica,” the movie comments on Japan’s geopolitical conundrum: caught between the two nuclear superpowers, striving for more independence from American influence, and balancing the demands of economic prosperity and modernization with the desire to preserve traditional Japanese values. After the runaway success of King Kong Vs. Godzilla (1962/3), which fused monster spectacle with a satire of the advertising industry, Rodan and Mothra too would have their opportunity to confront Godzilla, enriching the franchise with political commentary.

The central themes of power and violence are developed iteratively through the Shōwa monster movies, from the nuclear allegory of Godzilla, the environmental anti-imperialism of the two Mothra films, and on into the Ghidorah movies, which comment much more explicitly on imperial violence and conquest. Mothra’s first sequel, Mothra vs. Godzilla (retitled in the US as Godzilla vs. The Thing) was released early in 1964, and later that year Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster hit cinema screens as a winter blockbuster. The movie’s bombastic plot saw the virtuous Mothra persuade the quarrelsome Rodan and Godzilla to team up against the alien peril Ghidorah, a beast more threatening and dangerous than anything anyone had seen before.

Perhaps the single most notable aspect of Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster is its lighter, more family-friendly tone. Where once they represented different flavors of doom, Rodan, Mothra, and Godzilla now come to humanity’s aid and are openly celebrated as the triumphant heroes of the hour. This broader tonal appeal has sometimes been read as a disengagement from political themes, as the movie’s crowd-pleasing entertainment value is seen as overriding any attempt to sermonize on social or political matters. Noted Godzilla investigator Steve Ryfle, for instance, writes that in this movie “high-brow issues like nuclear weapons and commercialism are abandoned in favor of pure, fast-paced escapism.” But the central antagonism in the film—the clash between the alien Ghidorah and the trio of cooperating Earthly Kaiju—in fact extends the series’ engagement with international politics even more boldly than the previous entries in the Godzilla series.

In a short tongue-in-cheek article in a 2000 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Janne Nolan writes that Ghidorah’s first movie works as a compelling example of the benefits of international security cooperation. The movie “is a clear demonstration that even mutants, despite tiny brains and a Darwinian environment, can understand the imperatives of cooperative security when survival is at stake. Maybe policy-makers will be next.” Though Nolan is writing playfully here, this interpretation in fact has much to recommend it. Japan’s post-1945 constitution was written by the occupying US forces, and it placed firm restrictions on Japan’s ability to form an army of any kind. Over the following decades, this constitution and various additional security treaties that were added to it became increasingly controversial and unpopular across the political spectrum, culminating in violent protests in 1960. And there was plenty more happening abroad: China’s regional influence and nuclear weapons program were growing, and China tested its first atomic weapon two months before Ghidorah was released; the USSR was a strong and expanding regional presence; memory of the Korean War was painfully fresh; war raged, bloody and bitter, in Vietnam. Cooperative security, then (however reluctant and fragile), would be a theme that was at the forefront of many Japanese audience members’ minds in 1964.

As we have seen, the sequel Invasion of the Astro Monster (originally titled Godzilla vs. Monster Zero) followed in 1965, omitting Mothra and sophisticating the narrative. Where in his first appearance Ghidorah’s arrival on Earth had been a freak accident, in his second Ghidorah is cynically used against the Earth as part of an overtly imperialist venture by the Xiliens. Similarly, in Destroy All Monsters the Kilaak aliens hijack Earth’s monsters and unleash Ghidorah with the explicit aim of blackmailing humanity into submission. The Kilaaks announce that they come offering peace terms that humanity must accept or die; sacrifices must be made if the Kilaaks are to build the perfect world.

This rhetoric of peace is a particularly evocative element of the films’ representation of imperialism. Roman historian Tacitus famously wrote in Agricola, his history of the Roman conquest of Britain, that the Romans “make a desert and call it peace.” These words are spoken by Calgacus, a Caledonian war leader and resister of Agricola’s conquest, a “barbarian” Briton who Tacitus turns into an eloquent critic of the violence of the Roman Empire. Calgacus’s insight is that the bloodthirsty and warlike Romans, who conquer the entire world through slaughter, slavery, and pillage, cynically describe themselves as benevolent peace-bringers. Indeed, little has changed in the vocabulary of warlike empires: to this day, devastating imperial wars are justified as liberatory and civilizing, as the necessary violence that will bring enlightenment to the dark places of the world. Toho’s Astro-colonizers, too, repeatedly speak the language of peace and cooperation while preparing to annihilate or enslave humanity. In 1972’s Godzilla vs. Gigan (originally titled Earth Destruction Directive), Ghidorah is sidekick to the sinister robotic space-chicken Gigan, and once again both monsters are used against the Earth by an invading force of alien beings, this time the Nebula M aliens. In this one, huge cockroaches masquerading as humans are “striving to bring absolute peace to the whole world.” By this, the Nebula M aliens actually mean that they are plotting the eradication of humanity and the extractive exploitation of Earth’s environment and resources.

“Oh Glenn, I am governed by electronics”This masquerade, in which alien cockroaches appear indistinguishable from ordinary humans, is an interesting thematic overlap with a particularly politically charged Cold War form: the espionage thriller. It is of course no coincidence that the monster stories in Ghidorah movies are often complemented by espionage stories involving the human characters. This was due both to the explosive popularity of 007—Sean Connery had swaggered and snogged his way through Dr. No in 1962 and From Russia With Love in 1963, initiating a global sensation still going strong in 2021—and the rise of Japanese Yakuza crime films that were beloved by audiences. Importantly, many generic elements of Japanese crime and espionage stories (and their Western counterparts) translated particularly well to science fiction, including mind control, subterfuge, infiltration, and double-cross.

Some of the movies’ women are particularly important elements of the Cold War politics of the Shōwa Ghidorah stories. In Invasion of the Astro Monster, American astronaut Glenn’s (Nick Adams) Japanese fiancé Namikawa (Kumi Mizuno) is revealed to be in fact a Citizen of Planet X, where all women look identical—she has been sent by the ashen-faced Commander to seduce and surveil Glenn with the aim of recruiting him to the Xilien cause. Like a sexual temptress from an Ian Fleming novel, she has used her feminine wiles to compromise and manipulate our wisecracking male hero. However, in a campy yet emotionally powerful scene, she defies her programming to declare her authentic love for him—for which crime she is vaporized by her superior. “Our actions are controlled by electronic computers, not by human emotions,” explains the Xilien who coldly murders Namikawa. “When that law is violated, the offender is eliminated.” Likewise, in Destroy All Monsters, Kyoko Manabe (Yukiko Kobayashi) has a small metal receiver implanted into her earrings, and, robotically, she follows the Kilaaks’ every broadcasted command, blithely sowing destruction wherever she goes.

Brainwashing was a major cause of political panic in the late 1950s and early 1960s. American POWs, horribly traumatized by their torture in communist re-education camps, were filmed falsely accusing themselves of war crimes, refusing repatriation, and regurgitating communist propaganda. This extreme ideological indoctrination was dehumanizing, depersonalizing, humiliating, and appeared particularly terrifying because it seemed to show that the human brain could be rewired or manipulated to the extent not only that the prior personality was eliminated but, worse, that the victim appeared either blissfully unaware of or sycophantically grateful for their transformation. Very soon, however, the focus of the political panic sharpened, shifting from the suffering of the captured Americans to the possibility that repatriated soldiers could be reprogrammed into secret assassins whilst appearing, from the outside, to be respectable and well-integrated citizens.

In Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate (famously adapted by John Frankenheimer in 1962), for example, the stepson of a prominent anti-communist senator is brainwashed and used as a remote-control communist assassin. The double agent, unaware of his own programming, is memorably described as “Caesar’s son to be sent into Caesar’s chamber to kill Caesar.” Soon enough, of course, this would shift once more into a more generalized scaremongering about Soviet indoctrination, sleeper agents, and totalitarian mind control that clearly influenced Toho’s Ghidorah movies. The enemy who seems concerned for our safety but who secretly plots our violent demise—the double-crossing double agent, the indoctrinated infiltrator—was a very widespread Cold War bogeyman, and he remains with us today in the modified form of the secretive “lone wolf” terrorist living and moving among us.

“The standard message” of the science fiction film, writes Susan Sontag in 1966’s Against Interpretation, “is the one about the proper, or humane, use of science, versus the mad, obsessional use of science.” Later: “Science is magic, and man has always known that there is black magic as well as white.” The black magic of mind control is one of the most enduring aspects of Cold War political panic. In their attempts to “scientifically” understand Communist brainwashing, the CIA developed the MKUltra program, a set of gruesome torture sessions masquerading as scientific investigations into the limits of human endurance. This program (and the assumptions about the scientific possibility of directing the human mind that underpin it) has continued to have terrible ramifications into the present, as psychologists were brought in to develop the post-9/11 torture program, pseudoscientifically dignifying scandalous mistreatment by presenting it as a controlled and methodical process of scientific investigation. In each of these cases, black magic is not magic at all, but simply, and sadly, torture. Of course, it is overreach to suggest that the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are about CIA torture; but it is clearly true that brainwashing and mind control have always been deeply political concerns.

King Ghidorah: A Political DemonologyThe four Shōwa movies featuring Ghidorah are, then, remarkably thematically consistent. Alien invasion, subterfuge, mind control, and monster cooperation (a kind of Kaiju anti-imperialism) are central to each of them. Most fundamental, however, is the theme of power. Ghidorah is, after all, a King: a total sovereign, breathing fire, exercising absolute and arbitrary power over everything he surveys. It’s true that there is a lot of knockabout fun involved, but the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are also vibrant explorations of authoritarian power, of the political totalitarianism that was so powerful and such an omnipresent concern in the mid-20th century. Importantly, too, a major part of the appeal of the films is their ambiguity. It’s difficult, after all, to say exactly which empire Ghidorah’s villainous commanders are supposed to represent, and, in any case, pinning it down to one definite answer would only diminish the sloshy, sticky generosity of the metaphor.

But it is nonetheless interesting to think it through in terms of concrete possibilities. Since the relationship to the US was a matter of considerable controversy in 1960s Japan, the Astro-colonizers in these movies could well represent America—that most powerful and potentially violent of international actors, the occupier turned ally whose boot was slamming down heavily and noisily in Vietnam. The USSR was also a significant political concern, another expansionist superpower bearing down upon Japan; as we have seen, brainwashing was seen as a specifically communist tactic. But the Cold War period was also marked by precipitous decolonization and rapid, blood-soaked political reconfiguration. The French suffered humiliating and ruinous defeats in Indochina and the Maghreb, most notably in the Algerian Revolution, a bitterly violent conflict abroad that caused the downfall of the Fourth Republic at home. Britain fought dirtily in harrowing counterinsurgency wars in Kenya, Aden, Cyprus, Malaya, and elsewhere. Portugal, too, prosecuted a gruesome campaign in Angola that ended in ignominious defeat. Japan, of course, had its own share of Imperial shame.

Invasion of the Astro Monster makes explicit reference to this global unrest in a startling montage of documentary photography that follows the revelation of the Xilien betrayal.

In the 1960s, cities the world over, including Tokyo, were the stages of protests, unrest, and heavily militarized police crackdowns as groups representing a wide array of new political forces rose up against the established order. This clear visual reference to the global reconfigurations of power that were taking place in the long wake of World War 2 unambiguously situates the Xilien conquest in the tradition of Earthly political upheaval. The Xiliens could be the French, the Soviets, the US, Perfidious Albion—the British Empire—or even the militaristic Japanese Empire of recent memory. Destroy All Monsters, too, set in the utopian future of 1999, shows the fragility of international peace and its vulnerability to imperialist aggression. The futuristic society at the end of the Millennium, dedicated to cooperation and scientific discovery, is still easy prey to the calmly, arrogantly seductive Kilaaks, who are an amalgam of every negative trait ascribed to imperialists: parasitic, violent, manipulative, and smugly convinced of their own superiority. In the final analysis, it is precisely the fact that the Kilaaks, Nebula M aliens, and Xiliens represent imperialism in general, rather than any specific historical constellation, that gives these movies their power.

This condemnation of empire, of course, raises an interesting contradiction, or tension, with relation to the US. One of the defining ideological contradictions of postwar America is that it has managed to present itself as somehow “not an empire” despite its constant projection of militarized power across the planet. The demonization of the tactics of the duplicitous aliens in Invasion of the Astro Monster—a Japan-US co-production—is, for example, clearly in harmony with the political ends of American Cold War neo-imperialist ideology, and serves to cement US-Japan relations as much as it does to criticize them. That is, by using the Xiliens to caricature the crimes of the dying 19th century empires and showing the countries of the democratic capitalist West as an anti-imperial coalition defeating the villains, US-led imperial aggression is painted as a form of humanistic anti-imperialism. The fetishization of anti-imperial resistance is, after all, a core component of contemporary imperial ideology: think Star Wars or any number of similar genre pieces in which plucky Davids smash brutish Goliaths.

In summary, then, the Shōwa Ghidorah films are extraordinary documents of Cold War politics. As they were being made, the old empires were being smashed to the ground, and in the process imperial power itself was problematized and condemned as never before. In this context of global transformation, imperialism itself took on the appearance of senseless, cruel, and openly manipulative barbarism, and imperialists were known more openly as blackmailers, villains, and torturers—or, as Glenn puts it in Invasion of the Astro Monster, as “double-crossin’ finks.” What better metaphor, then, for the arbitrary despotism of empire than a colossal golden hydra remotely controlled by forked-tongued extortionists?

![]() Alex Adams is a writer based in North East England. He writes widely on popular culture and politics, and he is currently writing Godzilla: A Critical Demonology for Headpress Books. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexAdams5 and @GDemonology, or visit his website to read more.

Alex Adams is a writer based in North East England. He writes widely on popular culture and politics, and he is currently writing Godzilla: A Critical Demonology for Headpress Books. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexAdams5 and @GDemonology, or visit his website to read more.

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Thing on the Doorstep (2014)

Ok. I can already tell that a Lovecraft film-fest is going to be rough. Lovecraft's writings rarely translate well to the screen, this one is no exception.

Ok. I can already tell that a Lovecraft film-fest is going to be rough. Lovecraft's writings rarely translate well to the screen, this one is no exception.The Thing on the Doorstep (2014)

This one looks like it was a student film, except everyone looks too old to be a student.

The story sort of follows the Lovecraft short story, updated to modern times.

The cast is all unknowns. For most of them, this is their only film credit.

The filming has an odd sepia tone to it that I thought was more than a little annoying. It certainly gave it a solid straight-to-video vibe about it.

Again this video commits the worst sin a horror movie can; it was boring. I made it halfway through and ended up fast-forwarding to the end. I am sure I missed nothing. But given that I can only give myself half a point.

October 2021

Viewed: 10

First Time Views: 4.5

Review: SURVIVE THIS!! We Die Young RPG Core Rules (2021)

"Son, she said, have I got a little story for you

"Son, she said, have I got a little story for youWhat you thought was your daddy was nothin' but a...

While you were sittin' home alone at age thirteen

Your real daddy was dyin', sorry you didn't see him,

but I'm glad we talked...

Oh I, oh, I'm still alive

Hey, I, I, oh, I'm still alive

Hey I, oh, I'm still alive."

Pearl Jam, "Alive" (1991)

It's October. There's a chill in the air and there is a feeling in the air. Something that makes me reflective, chilly, and maybe a little melancholy. Sounds like the 90s to me. There is also a game that captures this feeling perfectly. Bloat Games' newest offering in the SURVIVE THIS!! series; We Die Young RPG.

I have been waiting to share this with you all and today is that day!

We Die Young RPG Core Rules

"Tell me do you think it would be alright If I could just crash here tonight?"

We Die Young RPG Core Rules is 372 pages with color covers and black and white interior art. The book is digest-sized, so the same size as Bloat Games other games. The game was Eric Bloat & Josh Palmer with art by Phil Stone and additional art by RUNEHAMMER & Diogo Nogueira.

For this review, I am considering the just-released PDF on DriveThruRPG that I got as a Kickstarter backer. The print book is due out soon.

Comparisons between this game and their first game, Dark Places & Demogorgons are natural and I think needed. I spent a lot of time with DP&D so I am looking forward to seeing how I can use this game with that as well. But first, let's get into the game proper.

The book begins with two dedications from the authors. I want to repeat them here since they set the tone not just for the game but also for my review.

Growing up in the 1980s was fun. Being in my late teens and 20s in the 1990s however, was AMAZING. January 1990 I was a university undergrad, living in the dorms with a girlfriend that driving me crazy (not in a good way), but a best friend I hung out with all the time. December 1999 I was married to that best friend, I had a brand new baby son, living in my new house, and was working on my first Ph.D. That's no small amount of change. But I never forgot that kid in 1990 with the flannel, goatee, Doc Martins, and long hair. This is the game for that kid. BTW "Layne" is Layne Staley, the former lead singer of Alice in Chains who died of a heroin overdose in 2002. If you can't remember EXACTLY where you were when you heard Layne, Kurt, Shannon, or Chris was dead, then this game is, to turn a quote "not for you."

Introduction

"With the lights out, it's less dangerous. Here we are now, entertain us."

Here we are introduced to the newest SURVIVE THIS!! game. The authors are upfront about their inspirations here; grunge music from the 90s and the games that were popular at the time. Having already gone through the book a few times it is a thread that weaved in overt and subtle ways, but it never feels overused, hackneyed, or clichéd. We are given some in-game background for why the Pacific Northwest is so full of supernatural strangeness and it is a fun explanation. But to quote the late, great Bard of Seatle I prefer it "always been and always be until the end." But it works well.

The basics of RPGs are covered and what you need to play. Next we get into character creation.

Character Creation

Character Creation"I'll be whatever you want. The bong in this Reggae song."

Character creation follows the same process as other SURVIVE THIS!! games and by extension most Old-School games. We are told from the word go that we can add material we want from the other SURVIVE THIS!! games.

Attributes are covered which include the standard six, plus the "Survive" attribute common to all SURVIVE THIS!! games. My first thought? My Dark Places and Demogons characters have grown up and moved to Seatle.

Like the other games in this family, Hit Points start with a 2d6 and increase by 1d6 per level regardless of class or race. Combat can be quite deadly in these games for people used to the hardiness of even Old-School D&D characters.

Saving Throws are different from D&D but the same as DP&D with the edition of the Magic save. This does make porting over characters and ideas from the other games pretty easy.

Alignment covers Righteous, Law, Neutral, Anarchist, and Evil.

Races

"All I can say is that my life is pretty plain, You don't like my point of view and I'm insane."

Here we get into the really new material. We have a bunch of new races for this setting. These include shapeshifting Doppelgangers, undead Ghouls, garden variety Humans, the immortal Imperishables, the ancient undead Jari-Ka, the various Realm-Twisted Fey (my new favorite, and I am sure I dated a Twitter Fey back then), Vampires (sparkles are optional), and Were-beasts of all stripes. If you played ANY RPG in the 1990s you know what you are getting here, but still, they manage to make it feel both new and old at the same time. New, because there is new potential here and old because they feel comfortably familiar; like that old flannel in the back of your closet or those beat-up old Doc Martens.

The races are well covered and you could easily drop them into any other SURVIVE THIS!! game or even any other Old-School game. They are really quite fun and I could not help but think of what characters I wanted to make with each one. This covers about 40 pages.

This is followed by a list of occupations with their bonuses.

Classes

"This place is always such a mess. Sometimes I think I'd like to watch it burn."

We Die Young is a class/level system. There 16 classes for this game. Some look like repeats from DP&D but are not really. They are updated to this setting and older characters. We are told that classes from the other SURVIVE THIS!! games are welcome here.

We Die Young is a class/level system. There 16 classes for this game. Some look like repeats from DP&D but are not really. They are updated to this setting and older characters. We are told that classes from the other SURVIVE THIS!! games are welcome here.Our classes include the Mystic (tattoos mages), Naturalists (potheads, I mean druids), Papal Pursuant (soldiers of God), Psions (Carrie), Revenant (Eric Draven the Crow), Riot Grrl (what it says on the tin), Rock Star, Serial Killer, Shaman (oh here are the potheads), Sickmen (homeless, as seen by Sound Garden), Street Bard, Street Fighters, Thralls (Vampire servants), Tremor Christs (psionically powered religious prophets), Warlock (steal power for otherworlds), and what I can only assume is an attempt to get a good review from me (just kidding!) the Witch.

The witch here is slightly different than the ones we find in DP&D. So there can be no end to the witchy goodness you can have by combining games.

That covers a healthy 50 pages.

Skills

The skill system for We Die Young is the same as DP&D. Though without checking it feels a bit expanded. You get points to put into skills and there are DCs to check. Very 3e. Or more like 3e IF it had been written in 1995. So, yeah, another solid point for this game.

Magic (& Psionics)

"Show me the power child, I'd like to say. That I'm down on my knees today."

Here is one of my favorite things in a game. There is a mythos added to the system here that is rather fun (see Spellcasters & Salt) as well as rules for Rune-Tattoos. Yeah, this is the 90s alright!

Now I have to say this. If adding a witch class is trying to get me to do a good review, then these spell names are outright flirting with me. Spells called "All Apologies", "Heaven Beside You", "Black Days", "Wargasm", "Super Unknown", and "Far Behind"? Yeah. That is hitting me where I live. And that is only the very tip of the iceberg.

Magic, Spells and Psionics cover a little over 60 pages and I feel they could have kept going.

Equipment

"What did you expect to find? Was there something you left behind?"

No old-school flavored game is complete without a list of equipment. This includes common items, weapons, and even magical items. Don't fret, it's not like there is a Magic Shop there. A "Health Locker" costs $50k and that is if you can find one.

The list of drugs is really interesting and fun. Look. It was the 90s. Everybody was taking drugs.

New to this setting are the Zapatral Stones. These are the remains of a meteorite that fell to Earth and hit the Pacific Northwest and Mount Rainer in particular. They have strange power and effects depending on the size of the stone and the color.

Playing the Game

"Whatsoever I've feared has come to life. Whatsoever I've fought off became my life."

Here we get our rules for playing the We Die Young game. We get an overview of game terms, which is nice really. New rules for Curses, Exorcisms, and Madness are covered. It looks like to me they could be backported to DP&D rather easily.

There is a fair number of combat rules. Likely this has come about from the authors' experiences with their other game Vigilante City.

We also get rules for XP & Leveling Up and Critical tables.

The World of We Die Young

"I'm the Man in the Box. Buried in my shit."

This is great stuff. This is the built-in campaign setting for We Die Young set place in a mythical and magical Pacific Northwest. the TL;DR? Grunge woke supernatural creatures. Ok, I can do that. I mean it is not all that different than ShadowRun right?

The setting of the PNW/Seatle on the 90s is covered well. I had many college friends that made the trek out to Seatle after our graduations (91 to 93 mostly), so I have some idea of what was happening on the ground level. Twenty-somethings like me seemed drawn to the place by some mystic siren song. A siren song with a Boss DS-2 distortion pedal.

Various associations/groups are covered, like Jari-Ka circles, Ghoul Legacies, Vampire Lineages, were-kin groups. Like I said, if you played RPGs in the 90s you know the drill. But again they are still both "new" and "old" at the same time. Kudos to the authors for giving me something new AND invoking nostalgia at the same time.

We also get some great locations of note and some adventure seeds which include some creatures.

Bestiary

"She eyes me like a Pisces when I am weak. I've been locked inside your heart-shaped box for weeks."

This covers all the creatures you can run into. The stat blocks are similar enough to Basic-era D&D to be roughly compatible. They are 100% compatible with other SURVIVE THIS!! games, so the excellent DARK PLACES & DEMOGORGONS - The Cryptid Manual will work well with this. In fact, I highly recommend it for this.

This covers all the creatures you can run into. The stat blocks are similar enough to Basic-era D&D to be roughly compatible. They are 100% compatible with other SURVIVE THIS!! games, so the excellent DARK PLACES & DEMOGORGONS - The Cryptid Manual will work well with this. In fact, I highly recommend it for this. There is a good variety of creatures. Angels, Demons, BIGFOOT! and more.

We get about 47 pages or so of monsters with stat blocks and an additional 10 pages of templates to add to monsters such as "Vampire" and "Radioactive."

Radioactive Bigfoot. I don't need a plot. I have that!

We get Adventure Hooks next. Roll a d100 and go!

The Appendix includes some Grung songs to get you into the mood. Some Seattle Grunge bands, some not-Seatle Grunge Bands, and some late 80's and 90's Alternative bands.

There is a list of movies about the era. A list of books. And finally the index and OGL.

Thoughts

Wow. What a really damn fun game!

If Dark Places & Demogorgons gave a "Stranger Things" 80s, this gives me a strange supernatural 90s.

It is exactly what I would have expected from the fine folks at Bloat Games.

My ONLY question about this setting is "Where are the UFOs and Aliens?" I mean NOTHING was bigger in the 90s than "The X-Files." I get that it is hard to cleave 90s Aliens to 90s supernatural (ask anyone that has tried to play WitchCraft AND Conspiracy X), but maybe a supplement is due out later? I would suggest grabbing DARK PLACES & DEMOGORGONS - The UFO Investigator's Handbook to add some X-Files flavored goodness to We Die Young.

Back in the early 2000s I had a game I was running, Vacation in Vancouver. It took place in the 90s and in Vancouver (naturally). These rules make me want to revive that game and see where I could take it now.

The bottom line for me is that SURVIVE THIS!! We Die Young RPG is a great game. The pdf is fantastic and I can't wait for my Kickstarter books.

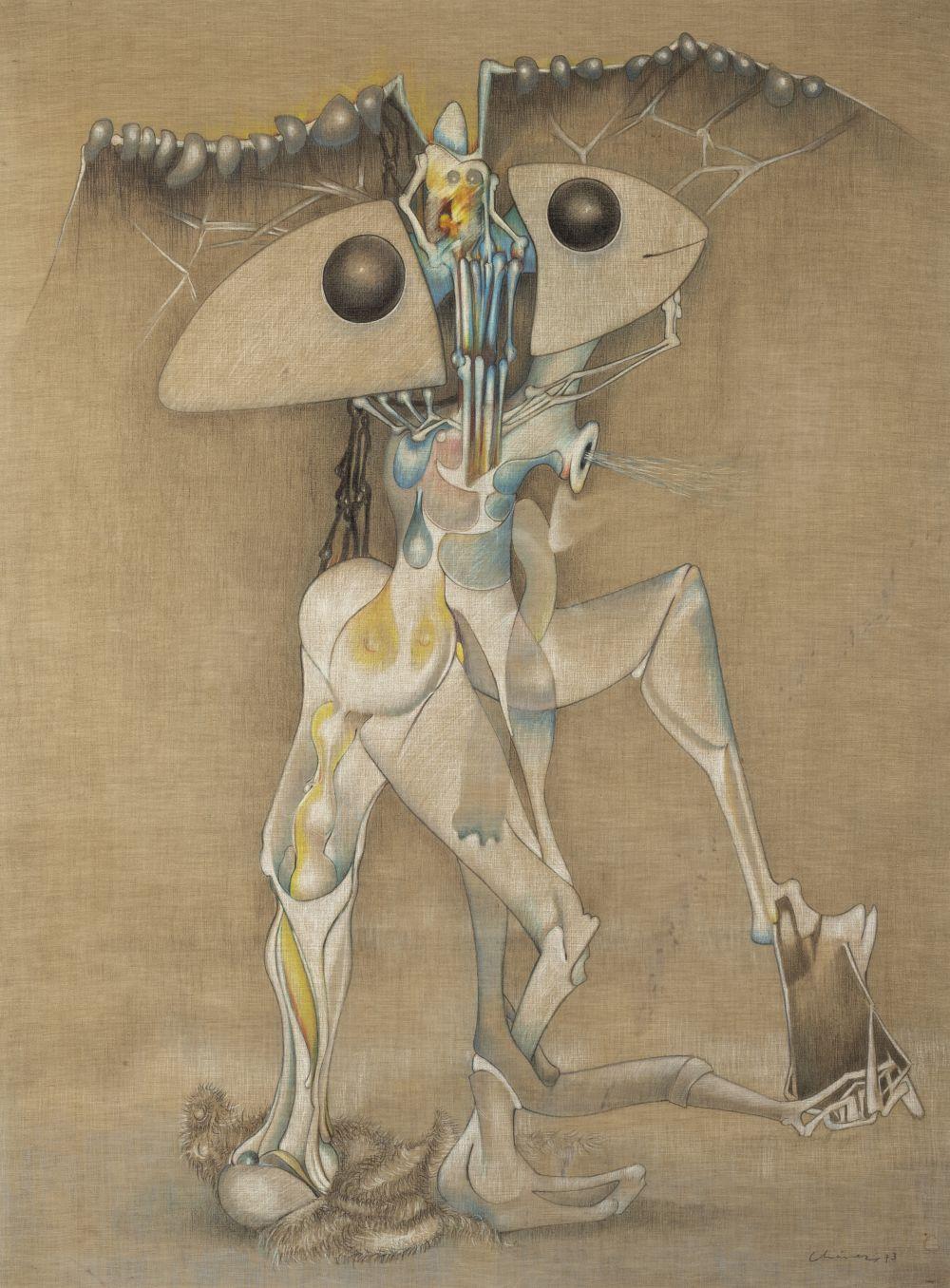

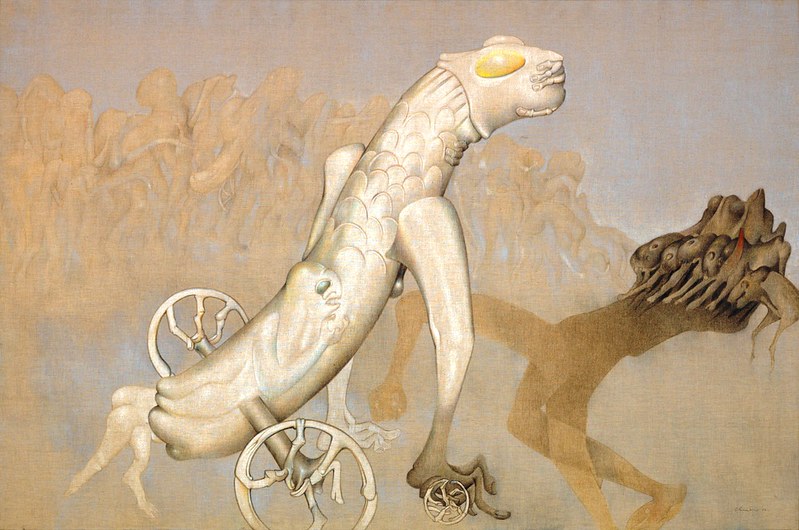

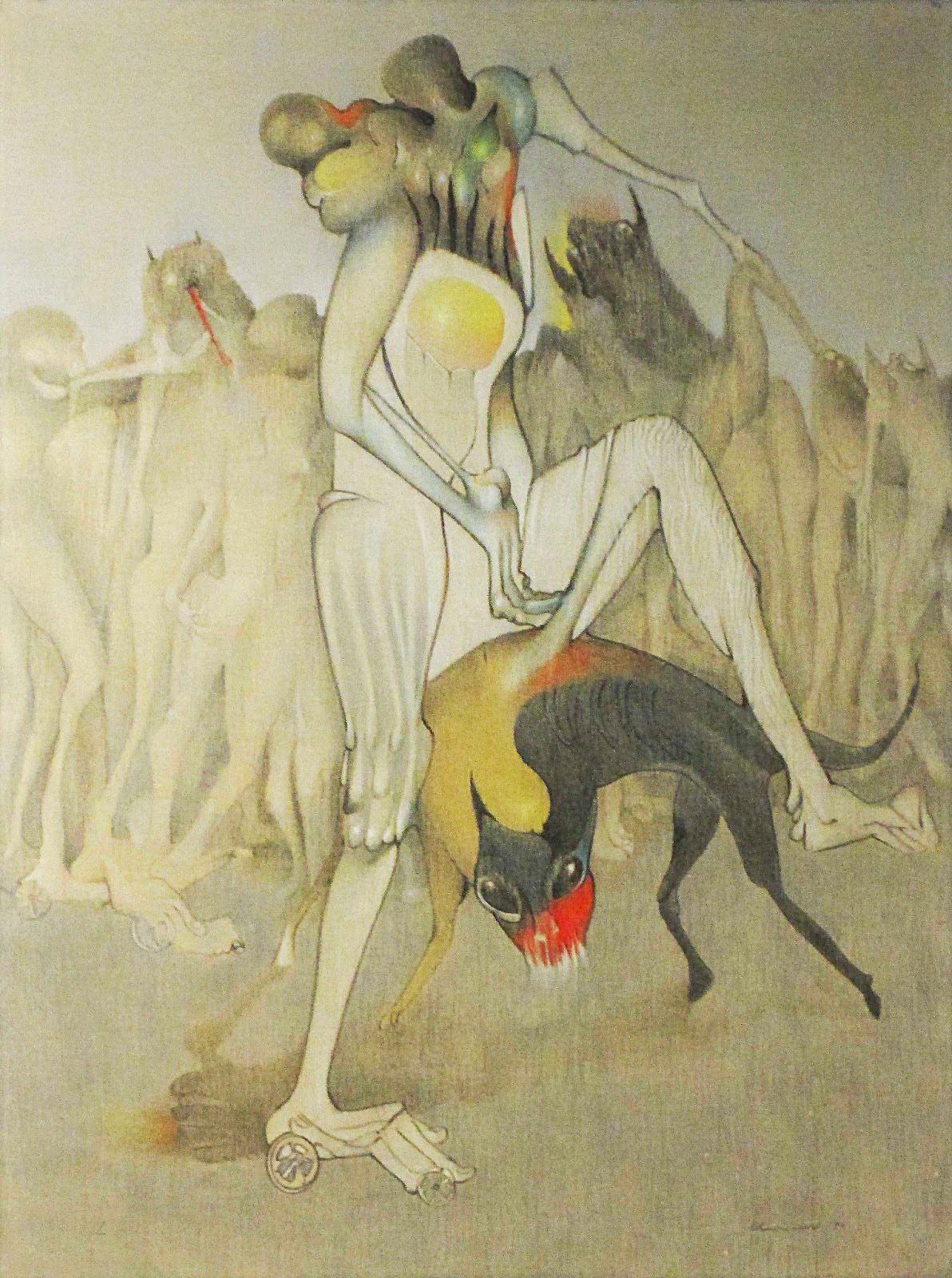

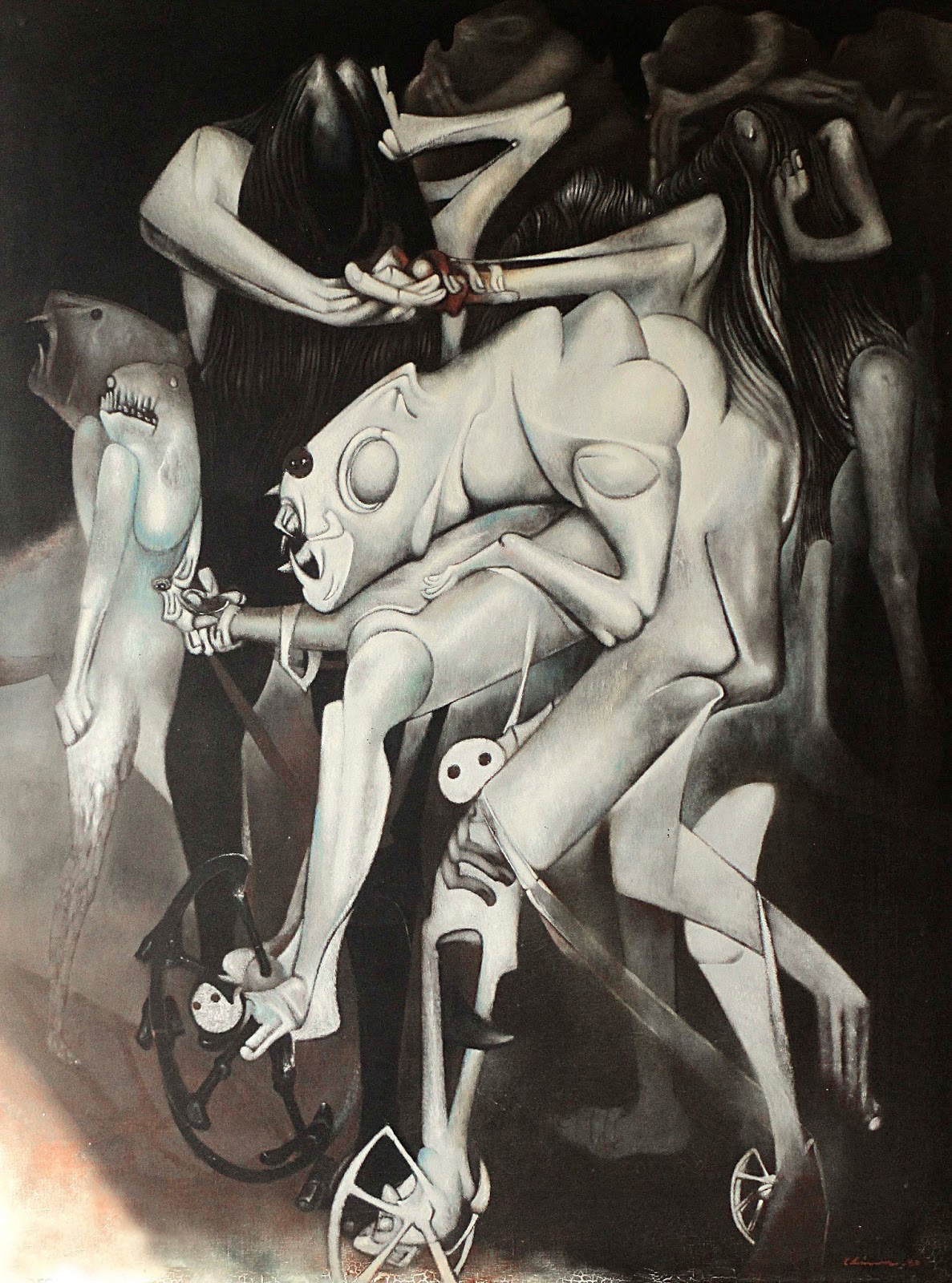

Gerardo Chavez Lopez (Peru, 1937 - )

October Horror Movie Challenge: From Beyond (1986) & Banshee Chapter (2013)

From Beyond (1986) might have been the very first Lovecraft-based movie I ever saw. I remember having the poster of it hanging in my room until I went off to college and then my brother had it in his room. I was pleased to also find a new movie based on the same Lovecraft short story and this film.

From Beyond (1986)

From Beyond (1986)I have been re-watching Star Trek: Enterprise, so I have been getting a fairly constant dose of Jeffrey Combs, but he looks so damn young here. Incidentally, the doors in the psych ward make the same noise as the doors on classic Trek.

This movie reunites Combs with Barbara Crampton, director Stuart Gordon, and producer Brian Yuzna. Gordon wanted a core set of actors he could work with to do a bunch of Lovecraft's stories. It's didn't quite turn out that way, which is too bad really. Crampton and Combs have great on-screen chemistry; especially considering they have no scenes where they are "romantically" linked. This is also the best of the batch of the Lovecraft movies. Having Barbara Crampton as Dr. Katherine McMichaels, a strong woman as a Lovecraft protagonist is fantastic. Combs does a great job as Tillinghast and you never once think of him as West from Re-Animator. Ted Sorel was also fantastic as the mad Dr. Edward Pretorius.

The movie holds up really well. The only things that seem "dated" in it are the hairstyles and technology. Even many of the special effects are still great.

I think I would have rather had a sequel to this one more so than Re-Animator.

Banshee Chapter (2013)

Banshee Chapter (2013)I sort of got the sequel in Banshee Chapter. This one combines the Lovecraft tale with the CIA's MK-ULTRA program. It features Katia Winter (who I adored in Sleepy Hollow), Ted Levine (from Silence of the Lambs and more recently The Alienist), and Michael McMillian (formerly of True Blood).

This features some "found footage" material, used to great effect in Blair Witch and Paranormal Activity and I think it works well here too. In this movie, the dimensional shifting abilities are from a chemical created by the CIA, and some short-wave radio broadcasts over Number Stations. I will tell you this, if you don't like jump scares, avoid this movie.

The mixing of Lovecraft's base story, secret CIA programs, weapons-grade hallucinogens, and creepy urban legends makes for an attractive mix.

Katia Winter plays Anne Roland, a journalist searching for her missing friend James Hirsch (McMillian) who filmed himself taking some of MK-ULTRA's super-LSD (DMT-19) and has now disappeared. She investigates the mystery and stumbles upon a recording of her friend picked up by a short-wave radio hobbyist who also happened to have worked for the NSA.

Ted Levin brilliantly plays Thomas Blackburn, a Hunter S. Thompson-like character. This is getting better all the time.

Anne views some CIA footage on the effects of the drugs. She watches one of the patients/test subjects get attacked by some creature in the dark. She also learns that DMT-19 is extracted directly from dead human pineal glands.

Anne finally gets in contact with Blackburn and they do some DMT-19 created by Blackburn's friend Callie (Jenny Gabrielle). Callie, who took some DMT-19 earlier, begins to show the same behavior that James did on the tape. They see creatures that they normally could not see. Much like how the Resonator does in From Beyond. At one point we see Callie, all white-skinned and black eyes, vomiting up a ton of blood. It's a lot of fun.

Monique Candelaria also appears as "Patient 14," one of the CIA test subjects. She would later make another contribution to Lovecraft media in "Lovecraft Country."

Maybe it is my ears, but I found it helpful to have the Closed Captions turned on.

We learn after some scares and a run in with Callie that Blackburn never gave Anne the drug. Though she can hear and see the creatures. We also find out the drug can be transmitted via touch and Blackburn was a subject of the CIA experiments when he was a teen.

Pretty good flick, but it sort of fell apart at the end. I read the director ran out of time for filming and you can kind of tell. But still, it was fun. They even name drop Lovecraft in it.

October 2021

Viewed: 9

First Time Views: 4

Monstrous Mondays: Alchemical Zombie

Ah. Monstrous Mondays in October. Nothing goes better together. They are peanut butter cups of my regular series postings. So let's get this first Monday in October started off right with a monster that screams Halloween monsters to me. Zombies.

After watching the Re-Animator trilogy this one is a, pardon the pun, a no brainer.

Zombie, Alchemical

Zombie, AlchemicalMedium Undead*

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1d8 (1d12)

Alignment: Chaotic [Chaotic Evil]

Movement: 150' (50') [15"]

Armor Class: 7 [12]

Hit Dice: 3d8+12*** (26 hp)

To Hit AC 0: 13 (+6)

Attacks: 2 claws, 1 bite

Damage: 1d6+3 x2, 1d4+3

Special: Fast, immune to turning, special abilities (see below)

Save: Monster 3

Morale: 12 (12)

Treasure Hoard Class: None

XP: 125 (OSE) 170 (LL)

Str: 19 (+3) Dex: 16 (+2) Con: 20 (+4) Int: 3 (-3) Wis: 1 (-4) Cha: 3 (-3)

Alchemical Zombies are created not by dark necromantic powers, but by forbidden sciences and alchemical means. They look like normal zombies, but the similarities end there. An alchemical zombie is fast, rolling normally for the initiative. While they are a form of undead, they are not reanimated by necromancy or evil magic, therefore they can not be turned by a cleric.

An alchemical zombie is mindless in its attacks. It will seek out any living creature and attack it with claws and bites. It will not stop until the living flesh it is attacking is torn to pieces. Some alchemical zombies will eat the flesh, but they do not need to do it for sustenance, but instead only as a dim reflection of memory of enjoying food. They do not rot beyond what their decomposed flesh has already done before their conversion and can last indefinitely. Even hacked-off limbs will continue to seek out warm blood and flesh to tear and rend. If there are no living creatures around the zombies will go into a passive stupor. They will "awaken" once a living person or creature comes within 60 ft of them.

In the process of making an alchemical zombie, alchemists discovered that by adding certain potions or chemicals can impart special powers on the zombie. These powers and their sources are detailed below.

Roll d20 Potion/Chemical Effect 1-3 Contol Undead Summons 1d4 normal zombie per day 4-5 ESP +1 to attacks, saves and AC 6-7 Fire Resistance +2 to saves vs. Fire damage 8-9 Giant Strength +4 to damage per attack 10-13 Healing / Troll Blood Regenerates 2 hp per round 14-15 Heroism +2 to attacks 16-17 Invulnerability +4 bonus to AC 18-19 Speed 2 extra claw attacks every other round 20 Super Heroism +4 to attacksIn all cases, these powers are reflected in the XP values above.

Only fire can truly destroy these creatures and they must be reduced to ash.

--

For today's entry I thought it might work if I returned the "To Hit AC 0" line to the stat block.

Miskatonic Monday #87: Haze

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

Name: HazePublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Name: HazePublisher: Chaosium, Inc.Author: Héctor Gámiz

Setting: 2010s USA

Product: Scenario

What You Get: Twenty-eight page, 4.43 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: Music to die for!Plot Hook: Could a strange teenage suicide be something more?Plot Support: Detailed plot, five handouts, four NPCs, one Mythos tome, one spell, and two pre-generated Investigators.Production Values: Solid.

Pros

# Potential introductory investigation# Solid investigation to conduct# Good mix of the interpersonal and the research # Decently done NPCs# Can be adjusted to any time in the 21st century# Nicely done handouts# Easy to adapt to Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game

Cons

# Involves suicide# Can involve the suicide of an Investigator# Requires a good edit and localisation

# Is the title appropriate?

Conclusion

# Solidly written investigation# Does involve suicide# Potential Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game scenario

October Horror Movie Challenge: Re-Animator (1985, 1991, 2003)

I can't do a Lovecraft film fest and NOT do the Re-Animator series. Yeah, it is so loosely based on Lovecraft's Herbert West, but it left a long shadow, for good or ill, on all future Lovecraft film adaptions.

I can't do a Lovecraft film fest and NOT do the Re-Animator series. Yeah, it is so loosely based on Lovecraft's Herbert West, but it left a long shadow, for good or ill, on all future Lovecraft film adaptions.Re-Animator (1985)

The first thing I notice about this is how freaking young Jeffery Combs is. Secondly how much gratuitous nudity there is in this. Third, re-animated humans are SUPER STRONG!

The scene where they reanimated Rufus the cat has stuck with me for years. Pretty much everyone in this is a little forgettable, save for Jeffery Combs as Herbert West and David Gale as Dr. Carl Hill. Yes, Barbara Crampton is in it as Meg doing what she does best, screaming and getting naked.

The version I just watched on the Midnight Pulp did not have the infamous "head giving head" scene, nor did it have the scene where West is injecting some of the reagent into himself like heroin. That might be in the sequel. Which is for later tonight. Though this one ends fairly definitively with West, Hill and Meg all dying in the end. Yeah...I know the title of the movie here.

I have seen this movie, I don't know now, maybe three dozen times. Never fails to amuse and entertain. Though it has been a few years since I last saw it and I am surprised which parts seemed to new to me.

I might need to get one of the newer Blu-Ray releases of it. Though that could just be my tired brain talking.

Bride of Re-Animator (1991)

Bride of Re-Animator (1991)Taking place after what is being called the Miskatonic Medical School Massacre, Herbert West and Dan Cain are still working on perfecting the re-animation process.

This movie, along with the first, completes the Lovecraft short story, more or less.

This one is also less campy than the first, which is interesting since the camp was one of the main features of the first one. Although West seems a little more unhinged in this movie. Almost out of character really.

There is also far less gratuitous nudity and blood in this one. Of it's there, just not the same as the thirst movie. I am getting the feeling the director and writers were trying to make a more serious horror movie. The scenes where the "Bride" is reanimated are very reminiscent of the Bride of Frankenstein with Else Lancaster. The lightning and the rain in the scene helps that feeling.

David Gale is back as Dr. Carl Hill, a fantastic bad guy to have really. This also marks one of his last roles before dying due to complications from open-heart surgery. Hill as a bat-winged flying head is really one of the joys of the film.

The ending though is pretty campy and crazy.

Beyond Re-Animator (2003)

Beyond Re-Animator (2003)Oh, I am going to be dragging in the morning. I knew of this movie but did not recall it until I went looking for Bride of Re-Animator on my streaming services. I found it and figured, let's make a night of it! Plus I need a new watch for this challenge.

This one is different from the other two even if it is supposed to be a direct sequel. We begin with the last night of the last movie. Young Howard Philips (hehe) is camping out in a tent with a friend when they hear someone go into their house. They investigate only to find his older sister, but they are quickly attacked by a zombie that kills his sister Emily. Wandering out of his house he sees the police take Herbert West into custody. West drops one of his re-agents and Howard picks it up.

It's13 years after those events and Herbert West is in prison experimenting on rats. Dr. Howard Philips has joined the prison hospital as the new doctor.

The movie was made in Spain and sadly has a less than polished feel about it. I was not surprised to hear it was direct to SciFi production, though I guess it was in some theatres overseas. The presentation is SD, not HD.

They try for a "Silence of the Lambs" feel to the prison, Arkham State Prison.

Elsa Pataky, aka Liam Hemsworth's wife, appears as Laura Olney a journalist who starts an affair with Dr. Philips.

Philips and West set up a lab space in secret to continue their experiments. Meanwhile, Laura keeps investigating West's background. The use of the original music for the research/investigation scenes is a nice touch.

West has discovered that the reagent is only half the solution, there is also this "Nano-Plasmic Energy" that jump starts all the cells. They try it on a pet rat and it comes back to life and 100% fine...well almost.

Laura goes to interview the prisoner that West revived, but is discovered by the Warden. Who promptly gets his ear ripped off. Laura refuses the advances of the Warden and he kills her too. They bring Laura back to life and use the Warden's NPE to make her normal, but it has some weird side-effects, like making her homicidal. West also brings back the Warden, but he manages to escape and steal the reagent. He starts killing prisoners and guards to bring them back to experience death over and over.

A prison riot breaks out and prisoners and the reanimated are all locked in together.

SWAT teams rush in to stop the rioters. We also learn what happens when a living person injects the pure reagent. Spoiler, it's messy.

This one ends with Herbert West walking out of the prison into the night.

It wasn't great, but it was fun.

October 2021

Viewed: 7

First Time Views: 3

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Dunwich Horror (1970, 2008)

The Dunwich Horror is one of Lovecraft's most enduring tales. We get the demented and evil Whately family. It is the story that gives us the most information on the Old One and Outer God Yog-Sothoth. There have been a number of movies based on it, but tonight I want to focus on two, both starring Dean Stockwell.

The Dunwich Horror is one of Lovecraft's most enduring tales. We get the demented and evil Whately family. It is the story that gives us the most information on the Old One and Outer God Yog-Sothoth. There have been a number of movies based on it, but tonight I want to focus on two, both starring Dean Stockwell.Double the Dunwich Horror and double Dean Stockwell!

The Dunwich Horror (1970)

So from the start, this movie is not 100% sure if it wants to be Lovecraftian horror of more typical 70s occult-themed horror.

I do love how the Necronomicon is given to a coed to return to the library like it was a copy of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Dean Stockwell is Wilbur in this one. He is really young and does a good job acting, BUT he is not a good Wilbur. That is due to the script really, not the acting. I guess they needed someone to charm Sandra Dee, and a deformed 10-year-old would not do the trick. Ed Begley (in one of his last roles) is our Dr. Armitage and he brings the right amount of pomposity to the role.

The biggest crime here is that the movie is so slow. The Whateley home in this movie is far nicer than it ever was in the Lovecraft tale.

The effects are not great, but fun. The image of Wilbur's brother is kind of cool.

There is a lot of conflating of the Old Ones with some sort of satanic aspect, which is fairly irritating, to be honest. But is it more irritating than Wilbur getting a "love interest?" Hard to say.

Among other things, this movie is notable for a very, very rare, blink and you will miss it, Sandra Dee topless scene. This was also near the end of her very prolific career. She would only appear in a few more TV episodes.

The movie ends with Dee's character, Nancy Wagner, pregnant with Wilbur's baby. I guess he would be in his 50s now. Sounds like a sequel to me! The Bride of Dunwich!

The Dunwich Horror (2008)

The Dunwich Horror (2008)This one has also been called "Witches: The Darkest Horror" and "Witches: The Dunwich Horror." This time the story moves to Louisana.

Dean Stockwell this time plays Dr. Henry Armitage. The movie is really not good, to be honest, but it is kind of fun. It watches like a Call of Cthulhu adventure; exotic locales, strange artifacts, old evil tomes, guest-starring Jeffery Combs (as Wilbur no less). Even John Dee, Olas Wormius, and the Knights Templar get name-dropped here. Olas even shows up in a swamp for some reason.

Moving the location to the far south is an interesting one. I am sure in Lovecraft's time New England had its share of strange locales, but now on a larger scale the same "other place" is served by the backwoods southern parts of the country. Or I might be giving the filmmakers too much credit. I also can't tell if the effect of Wilbur being "slightly out of this dimension/time" is interesting or irritating.

While it is not Lovecraft's Dunwich Horror and it is not very good, it kept me watching to the end.

So where are we at now? I think it is time for another Dunwich Horror movie, this time make it closer to the Lovecraft tale and get Dean Stockwell to play old man Whateley!

October 2021

Viewed: 4

First Time Views: 2

Last Flight of the Templars

It is Friday, October 13th, 1307. For over two hundred years, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, commonly known as the Knights Templar, has dedicated itself to protecting Christians making their pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Blessed by the Church and an official charity, the militant order of monks has become a power unto itself, a series of Papal bulls having placed the order above local laws, rendering them exempt from taxes, borders, travel restrictions, and legal oversight from any power short of the Papal Throne itself. In addition to protecting the Holy Land and participating in numerous Crusades against the infidel, the influence and power of the Templars has spread far beyond Outremer, primarily through the clever management of the vast tracts of lands given to the order as gifts, but also through the financial and banking network that it developed, ensuring the safe and transferred transit of credit. Yet in recent years, the reputation of the militant order of monks has suffered. Military defeats have forced it out of the Holy Lands and lost it access to the sites it was supposed to protect and there rumours of mysterious rituals and misdeeds, ranging from idol worship, sacrilege, and denying Christ to financial corruption, fraud, and secrecy. Then there are fears that the Knights Templar wanted to establish its own state in Europe, equal to any kingdom. Lastly, many of those kingdoms, including their monarchy and their nobility owed vast debts to the Knights Templar. It was for these reasons that the Templars fell from grace and from power.On the morning of Friday, October 13th, 1307, French forces, on orders from King Philip IV of France with permission from Pope Clement V, moved in secret to arrest dozens of Knights Templar in the Templar’s Parisian stronghold, the Enclos du Temple, including their Grand Master Jacques de Molay, and their Commander of Normandy, Geoffroi de Charney. Both would ultimately be charged with heresy, excommunicated, and burnt at the stake. On the morning of Friday, October 13th, 1307, as the Enclos du Temple was assaulted by French troops, Grand Master Jacques de Molay would his last orders. Faced with betrayal and defeat, he commanded the last Templars to take the secrets of the order to safety. They would be the last thirty to escape the fallen stronghold and theirs would be a perilous journey across Europe in search of sanctuary, harried all the way first by forces loyal to King Philip, and then the Inquisition. Did they find sanctuary and do they ever discover the true secrets of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon?

It is Friday, October 13th, 1307. For over two hundred years, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, commonly known as the Knights Templar, has dedicated itself to protecting Christians making their pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Blessed by the Church and an official charity, the militant order of monks has become a power unto itself, a series of Papal bulls having placed the order above local laws, rendering them exempt from taxes, borders, travel restrictions, and legal oversight from any power short of the Papal Throne itself. In addition to protecting the Holy Land and participating in numerous Crusades against the infidel, the influence and power of the Templars has spread far beyond Outremer, primarily through the clever management of the vast tracts of lands given to the order as gifts, but also through the financial and banking network that it developed, ensuring the safe and transferred transit of credit. Yet in recent years, the reputation of the militant order of monks has suffered. Military defeats have forced it out of the Holy Lands and lost it access to the sites it was supposed to protect and there rumours of mysterious rituals and misdeeds, ranging from idol worship, sacrilege, and denying Christ to financial corruption, fraud, and secrecy. Then there are fears that the Knights Templar wanted to establish its own state in Europe, equal to any kingdom. Lastly, many of those kingdoms, including their monarchy and their nobility owed vast debts to the Knights Templar. It was for these reasons that the Templars fell from grace and from power.On the morning of Friday, October 13th, 1307, French forces, on orders from King Philip IV of France with permission from Pope Clement V, moved in secret to arrest dozens of Knights Templar in the Templar’s Parisian stronghold, the Enclos du Temple, including their Grand Master Jacques de Molay, and their Commander of Normandy, Geoffroi de Charney. Both would ultimately be charged with heresy, excommunicated, and burnt at the stake. On the morning of Friday, October 13th, 1307, as the Enclos du Temple was assaulted by French troops, Grand Master Jacques de Molay would his last orders. Faced with betrayal and defeat, he commanded the last Templars to take the secrets of the order to safety. They would be the last thirty to escape the fallen stronghold and theirs would be a perilous journey across Europe in search of sanctuary, harried all the way first by forces loyal to King Philip, and then the Inquisition. Did they find sanctuary and do they ever discover the true secrets of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon?This is the set-up for Heirs to Heresy, a roleplaying game published by Osprey Games in which the last thirty free members of the Knights Templar carry the order’s great treasure and secret to sanctuary—to Avallonis. Avallonis may be a mystical dimension that only the gnostic Templars know how to access; a demonic realm to which the all the souls of the Templars are bound to; a faerie city, shrouded in mist with gleaming silver towers; the city of Lisboa where its friendly King will shelter the Templars from the wrath of the King of France and his lackey, the Pope; a state of mind or even a second word that will grant them eternal reward; and ultimately, even a lie… As to the great treasure, it might be the Grail, the Lineage of Christ, the idol of Baphomet, the Library and Seal of Solomon, or something else. The exact nature of both destination and treasure are up to the Grand Master—as the Game Master is known—to decide, although the length of the flight from Paris will heavily influence the former. The further the destination from Paris, the longer the campaign. Thus, if the destination is London, then the campaign will be relatively short, whereas Malta, owned by the Knights Hospitaller, sister order to the Knights Templar, would be a longer journey and thus a longer campaign. Similarly, The Grand Master will also need to set the degree of Esoterica available in the campaign and thus potentially, the Player Characters. This can be mundane, infused, or mystical, and the higher the degree of Esoterica, the more likely that magick will play a role in the campaign, including the foes that the Player Characters encounter. Finally another limiting factor upon an Heirs to Heresy campaign is the number of Templars who escaped Paris—thirty. If they all die before any one of them reaches sanctuary with the treasure, then both the secrets and the last treasures of the Knights Templar will have been lost.

Of course, Heirs to Heresy is not the first roleplaying game to explore this legend, designer John Wick having done so with Thirty in 2005. Although they share similar themes, Thirty emphasises the esoteric, whereas Heirs to Heresy explores that aspect of the Templar legend as a range of options. The other difference, of course, is that what constitutes as safe and good roleplaying is today is openly discussed and stated. Thus, Heirs to Heresy is up front about what is. In the foreword, the author rejects the adoption of the iconography of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, the Knights Templar by hate groups which espouse white supremacy, religious intolerance, and persecution. It is also clearly stated that whilst Heirs to Heresy draws very much upon the history and religions of the fourteenth century, it is not written as a historically accurate roleplaying game. Rather it blends history, mystery, and legend to create the potential for exciting stories—much like a film or television series would. Ultimately, it is more historical fantasy, and that includes the types of characters that the players can roleplay. The Knights Templar recruited from France, Germany, England, the Iberian Peninsula, and Italy, as well as Scandinavia, the Middle East, North African, and other Mediterranean countries. As long as a Templar is a devout Catholic, there is no bar in terms of origin, or indeed, his or her gender.

A Knights Templar is defined by six Attributes—Might, Vitality, Quickness, Intellect, Courage, and Spirit as well as fifteen skills. The Attributes typically range between zero and four, and skills between zero and five. To first create a Knights Templar, a player decided whether his character is a Dedicated Knight or a Versatile Knight. This will determine the spread available for his attributes. A Dedicated Knight has a mix of higher and weaker Attributes, whilst a Versatile Knight has a more balanced range. Similarly, whether a Templar’s training, either Focused training or Well-Rounded training, determines whether he has mastered one skill if Focused training, or a wider range of skills if Well-Rounded. With Focused training, a Templar has fewer skill points to assign, but two skills can be high, whereas with Well-Rounded training, there are more points, none of them can be high. Notably, a Templar does not have any combat skills or a Horsemanship skill. Every Templar is supposed to be skilled in both, so they are covered by his Attributes rather than dedicated skills. This is in addition to determining what the character looks like, his nationality, whether or not he has seen combat, how far he has travelled, his degree of spirituality, when he became a Templar, and so on. A player can also roll for quirks for his Templar and lastly choose some relationships with his fellow Templars.

Our sample Templar is Gudbrand Signysdottir, originally from Scandinavia, who travelled to Constantinople with her merchant father. Although he was killed by bandits, she saw how fiercely the other members of the caravan were protected by a band of Templars. Scarred in the attack, she decided to join the Templars and dedicate her life to the White Christ rather than return home where her brothers would take their father’s business.

Name Gudbrand Signysdottir

Nationality Scandinavia

Languages: French, Latin, Old Norse

Quirks: Exceptionally long hair, scar over one eye

ATTRIBUTES

Might +1 Vitality +1 Quickness +3 Intellect +2 Courage +3 Faith +2

SKILLS

Athletics 3 Awareness 3 Battle 3 Craft – Courtesy 3 Explore 3 Healing – History – Hunting – Inspire 3 Insight 3 Persuade 3 Religion 3 Stealth – Travel 3

HEALTH

Maximum 15 Crippling Blow 5

COMBAT

Melee Attack +4 Melee Damage Bonus +2

Ranged Attack +5 Ranged Damage Bonus +5

Defence 18

Damage Reduction 7

WEAPONS

Longsword (1H) d12 (On a 1: ignore Damage Reduction)

Londsword (2H) 2d8 (On two 1s: ignore Damage Reduction)

Dagger d6 (On a 1: ignore Damage Reduction)

Mace 2d4 (On a 1: permanently reduce Damage Reduction by 1)

Axe d8 (On a 1: shatter shield, or reduce Damage Reduction by 1)

Crossbow d10 (On a 1 or 2: ignore Damage Reduction)

ARMOUR

Chainmail 5 Damage Reduction

Shield +2 Damage Reduction

Mechanically, Heirs to Heresy is straightforward. To perform a Test, a character’s player rolls two ten-sided dice and adds an Attribute and a Skill to beat a target. A task which requires effort has a target of fifteen, challenging is eighteen, and difficult is twenty-one. If the result beats the target and consists of doubles, it is a critical outcome. This means it is done with a flourish, perhaps faster, with a better effect, or similar. In combat, it means double damage. If the task is made with Advantage, three ten-sided dice are rolled and the best two selected. Conversely, if the task is made at a Disadvantage, three ten-sided dice are rolled and the worst two selected. Advantage can be gained from the situation or one Templar can grant by supporting another. Notably Heirs to Heresy does include fumbles in its rules, because the Templars are meant to be competent and because fumbles are boring.

In addition, as God’s chosen warriors, every Templar can bring his faith and commitment to bear on his situation. To reflect this, he has Faith points to spend on various effects, including adding his Faith Attribute to a single Test, damage total, or reducing incoming damage by the same, to reroll a single Test, and if they factor into a campaign, power esoterica, Gifts, and Relics. Faith points are recovered slowly, a point every Sunday morning or by spending an hour in deep prayer at a Church or Catholic Holy Site. The latter requires a Test. However, Faith points are lost if a Templar breaks his vow of chastity, steals from the less fortunate, fails to pray upon awakening, or leaves a fellow Templar behind who could not have been rescued.

Combat is slightly more complex, but throughout Templars intended to be highly competent and capable combatants. In the main, the opponents a Templar will face are Mobs and Fearsome Foes. Mobs are either particularly courageous or fanatical to want to attack Templars, who can easily outfight them. A Templar always goes first and kills or defeats one member of the Mob per point of damage inflicted, whilst a Mobs only acts when a Templar fails to deal damage. Thus the Templar will in general have the upper hand and only when he fails will be vulnerable.

A Fearsome Foe represents a challenging opponent who fights like a Templar and can attack first before a Templar can act. Initiative is handled by pulling tokens out of a bag—one colour for the Templars and one for the Fearsome Foes, and when one colour is drawn from the bag, one of its associated combatants can act. Combat covers manoeuvres such as furious blows, defending, parrying, and so on. One interesting element of combat occurs when damage is rolled. An attacker can hope to roll high and simply inflict a large amount of damage after Damage Reduction has been deducted, but if a one is rolled with several of the weapons the Templars commonly wield, the damage ignores Damage Reduction. What this means is that an attack can inflict damage if even the damage roll is low. Other weapons have different effects when a one is rolled. When a Templar suffers damage greater than his Crippling Rating, his player begins ticking off boxes on his Templar’s character sheet, which can be stunned, bleeding, broken limb, or worse.For example, Gudbrand Signysdottir and her companions have fled the chapterhouse in Paris and reached the outskirts of the city where they encounter a patrol consisting of two knights—both treated as Fearsome Foes and a Mob of foot soldiers. They are challenged and combat ensues, her companions engaging the Mob and one of the enemy knights, whilst Gudbrand Signysdottir faces off against the other. When the Grand Master draws the token for the NPCs and decides that the knight will charge and attack. She rolls the two ten-sided dice and adds the knight’s Attack bonus of +6. This roll is made at Disadvantage. She rolls two, five, and ten, and whilst the five and ten are enough with the Attack bonus, this at Disadvantage, so the Grand Master must choose the worst two rolls. The two and the five, plus the bonus are not enough to beat the Gudbrand Signysdottir’s Defence of eighteen. As his second action, the knight presses the attack. Her roll of seven, nine, and the bonus is enough to beat Gudbrand Signysdottir’s Defence. The knight’s damage roll is four plus six, for a total of ten, which when reduced by Gudbrand Signysdottir’s Damage Reduction of seven, means she suffers just three points of Health damage.

When one of the players’ tokens is drawn, her player decides that it is now Gudbrand Signysdottir’s turn to act and like the knight, she has two actions. The first is to attack, striking at the knight with her Longsword. Gudbrand’s player rolls eight and eight—which indicates a critical strike and doubles damage—and adds her Melee Attack of +4. The total is twenty, which means that the attack is a success. This definitely beats the knight’s Defence of sixteen and the damage roll is a twelve-sided die plus her damage bonus of +2, doubled of course for the critical result. The result is nine, plus the damage bonus, doubled for a result of twenty-two. The knight’s Armour rating of seven reduces this to fifteen, which is deducted from the knight’s Stamina of eighteen. As her second action, she pulls back and decides to Parry against the next attack. This means that any attack against her will be at Disadvantage.Beyond the core rules, Heirs to Heresy adds simple rules for combat, and in terms of the campaign, rules for travel and pursuit. Travel is handled via Travel Tests and becomes more difficult if the Templars have to leave the road, with failures leading to their becoming lost running out of supplies, enemies catching up with them, having an obstacle encounter, and so on. The Templars begin play with a pool of Pursuit points, one per Player Character, and they are accrued for being seen, engaging in combat, being pursued by an Inquisitor, and more. The Grand Master can spend these to have the Templars encounter a patrol of guards, penalise Downtime activities, and other activities. When they stop at places of safety on their journey, whether in the wilderness or civilisation, the Templars can attempt Downtime actions. For example, Conceal Trail might enable them to reduce their Pursuit points, find someone to aid them, spread rumours to throw off their pursuers and so reduce their Pursuit points, train to gain Advantage on a roll.

In terms of experience, a Templar can acquire Advancement Points and Gifts. A Templar can acquire a Gift once every four sessions or so, such as Armour of God, which increases his Damage Reduction by a Templar’s Faith Attribute, but the player cannot spend Faith Points to reduce damage; Nobility, which enables a Templar to request lodging from peasantry or royalty alike; and Spiritual Well, which gives a chance to recover the first Faith Point spent each day. Advancement Points are earned for making Critical rolls and can be spent during Downtime to increase Skills, to unlock Relics, and to learn Esoterica, the latter including Magicks, Blessings, and Martial Esoterica.

Learning Magicks means learning esoteric spells and the gnostic unlocking of the universe’s secrets through greater mystical understanding, and requires a Templar to study the Library of Solomon. This grants the Templar the Gnosis skill and access to an increasingly harder to cast circles of spells, such as Angelic Light or Obscured From Man’s Eyes. The Third Circle includes Bind Angel/Demon and Resurrect the Dead. Blessings are granted by the Saints, such as St. Adrian, who as the Patron Saint of Guards, grants Advantage on Awareness Tests made when keeping watch or trying to detect ambushes, or St. Christopher, who as the Patron Saint of Travelling, eases travel, enabling a Templar to spend a Faith Point to automatically find a safe place to shelter for the night. It is up to the Grand Master how a Templar comes to learn a Blessing, though he needs a high Piety to learn each one. The one suggested method is having access to the Holy Grail, but Templar might easily be granted through great acts of piety or a gift from a sympathetic member of the church. Lastly, Martial Esoterica such as Agile Climber, Hammering Blows, or Sword Savant are mundane abilities that can be learned or taught from training, meditation, and a host of other sources.

Of the three types, Martial Esoterica is the easiest to learn and include in an Heirs to Heresy campaign. Both Magicks and Blessings are more difficult, and not only require the Grand Master to decide whether her campaign is infused or mystical in nature, but also what the source for either is going to be. There are obvious choices here—the Library of Solomon for Magicks and the Holy Grail for Blessings, and if the Grand Master decides that either of these has a role in her campaign, especially as the treasure that which Grand Master Jacques de Molay has bid the Player Characters take to safety, that treasure becomes doubly important. It not only serves as their burden, but also a source of their mystical power, and ultimately, their faith made real.