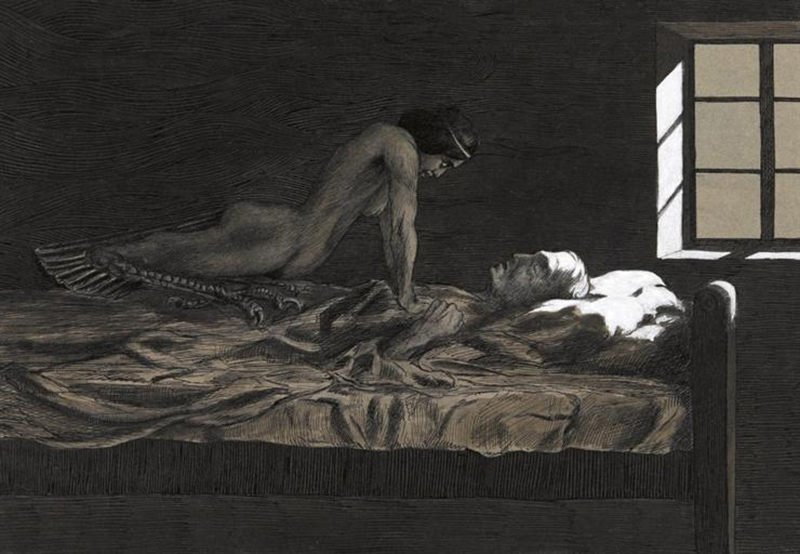

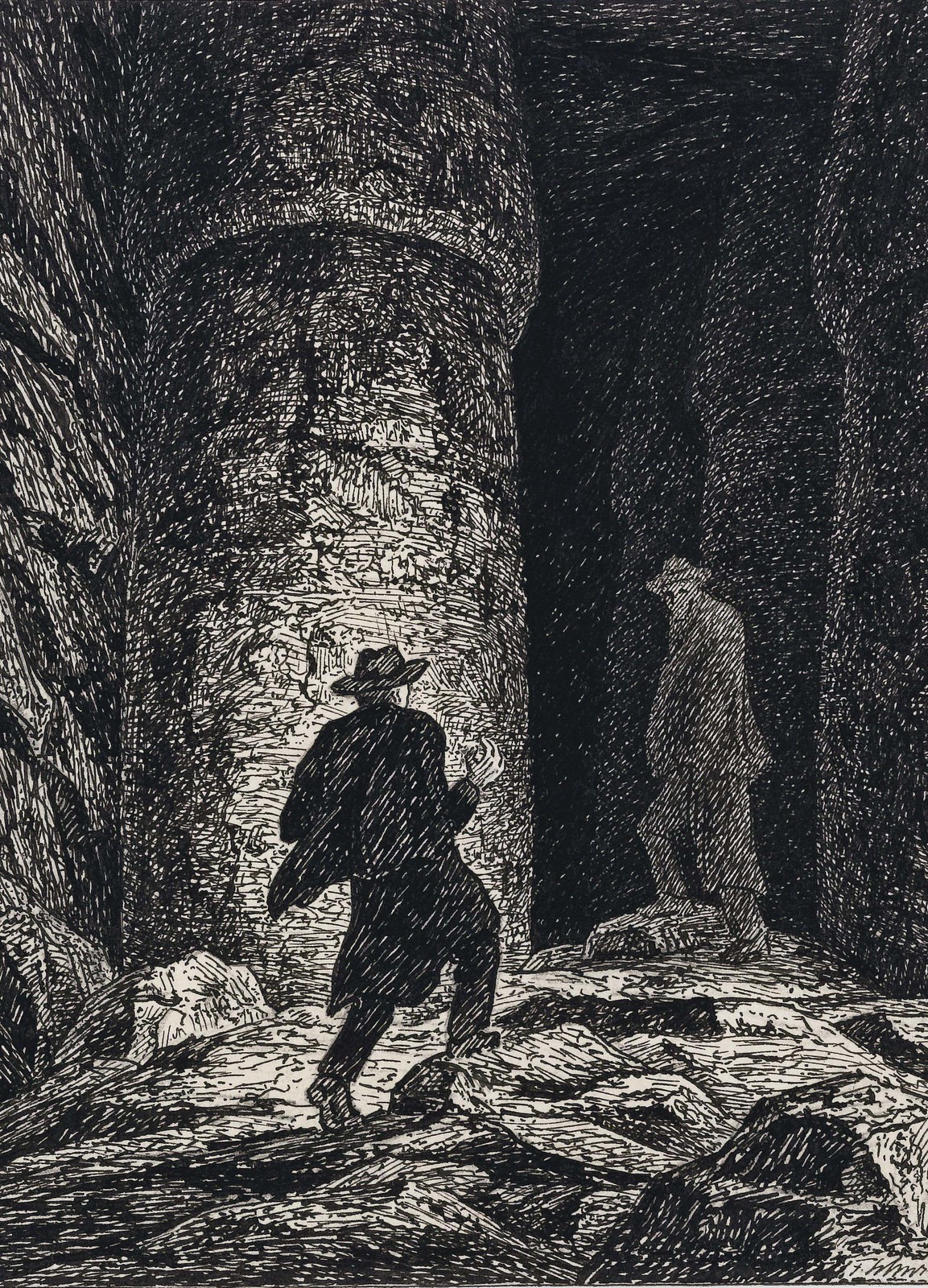

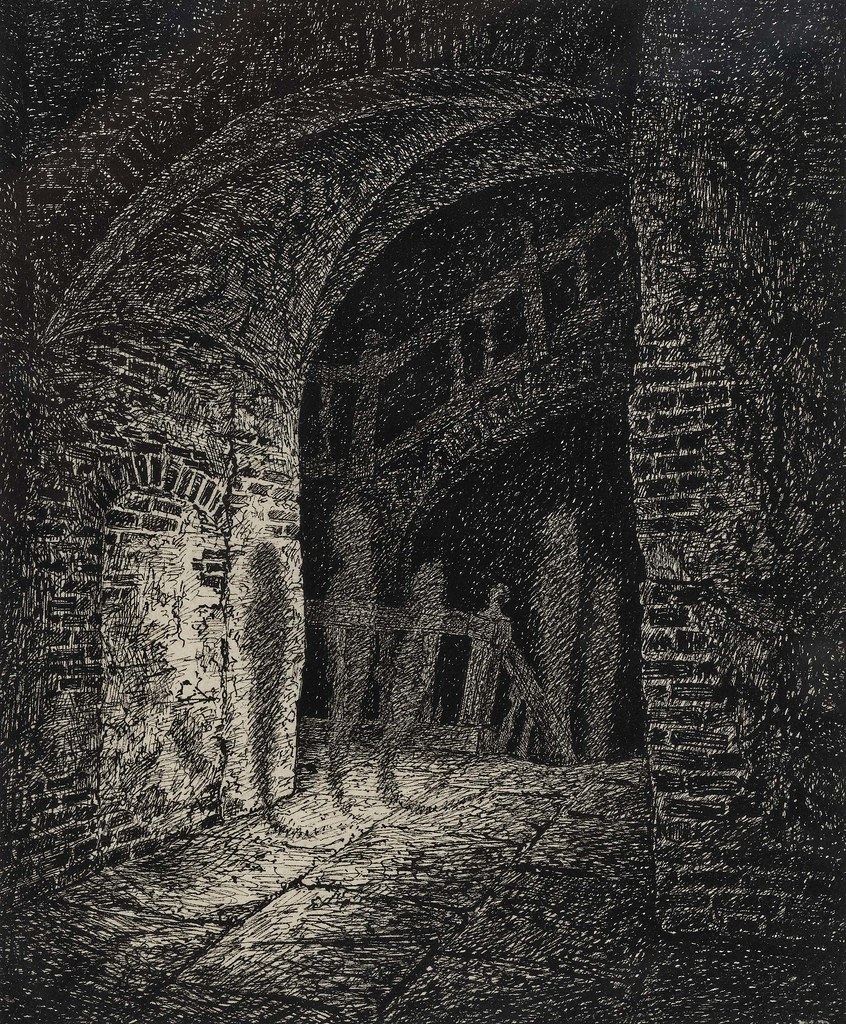

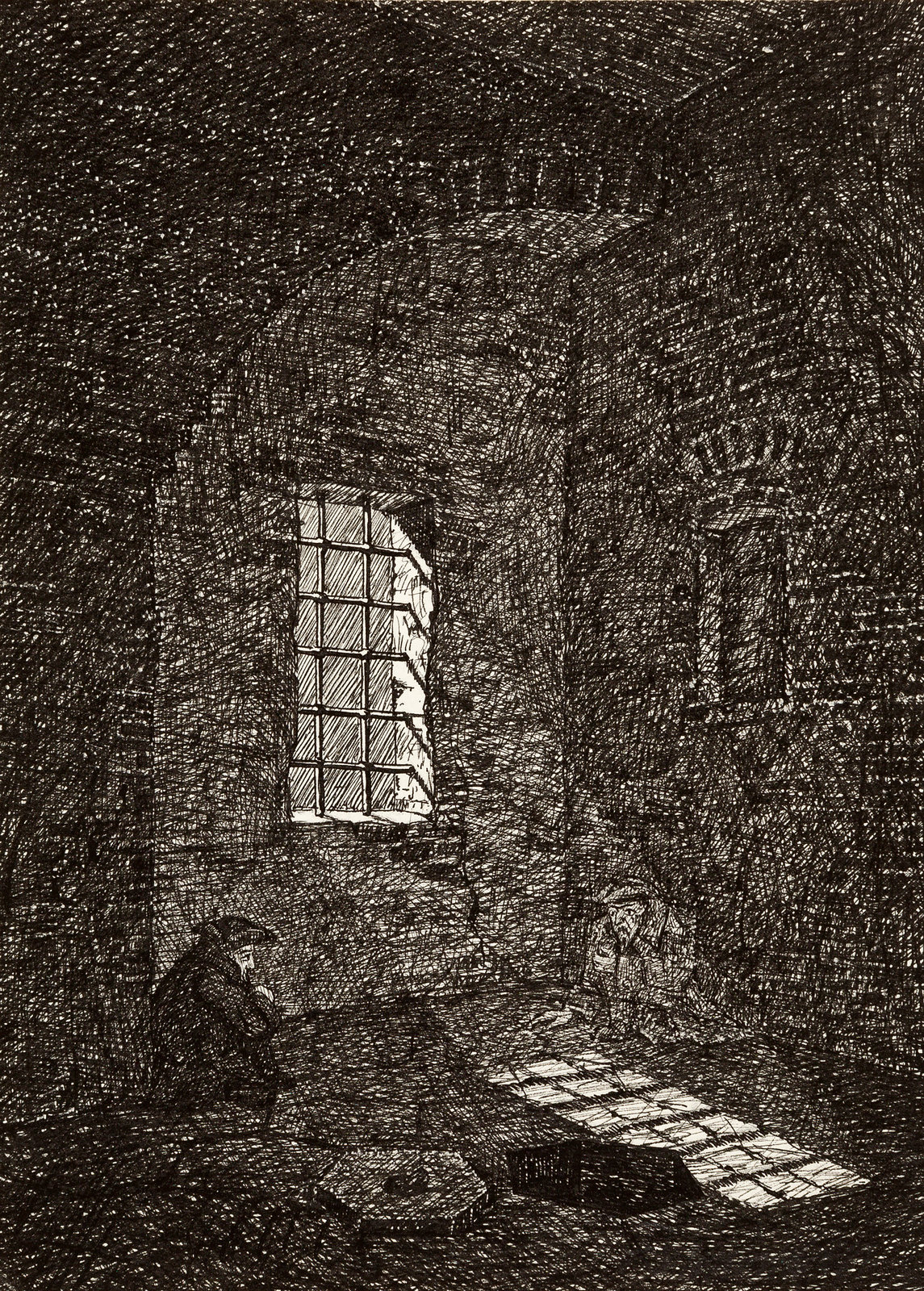

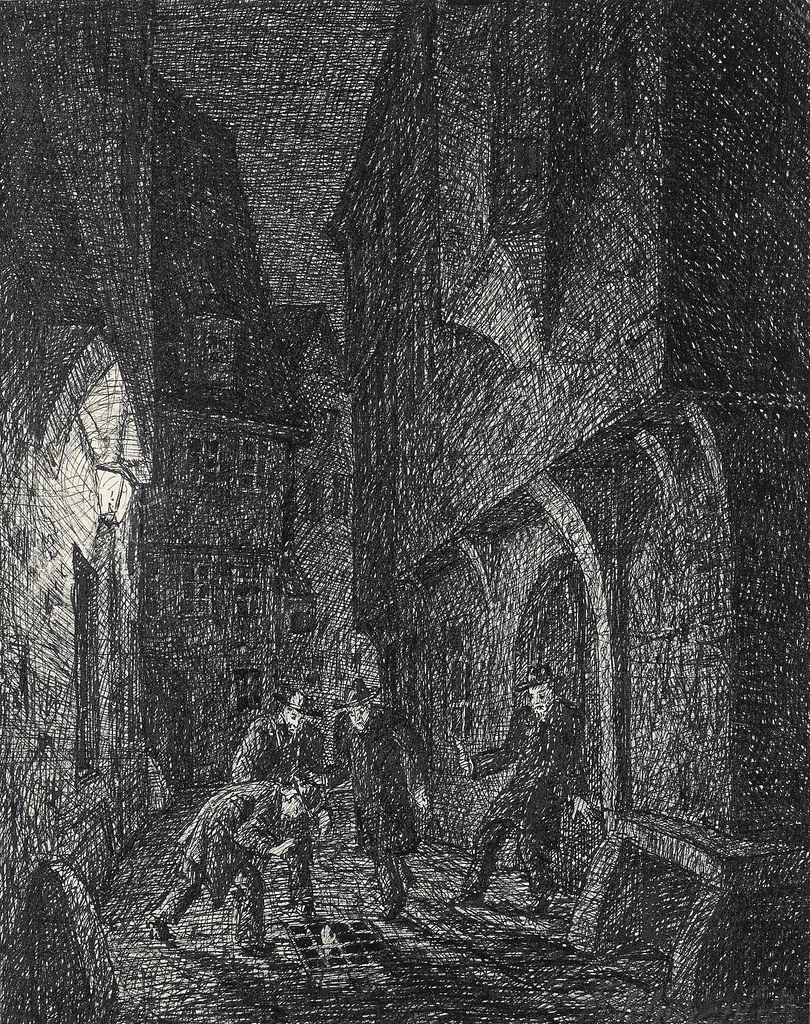

Giovanni David - A Nightmare, 1775-80

Artwork found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

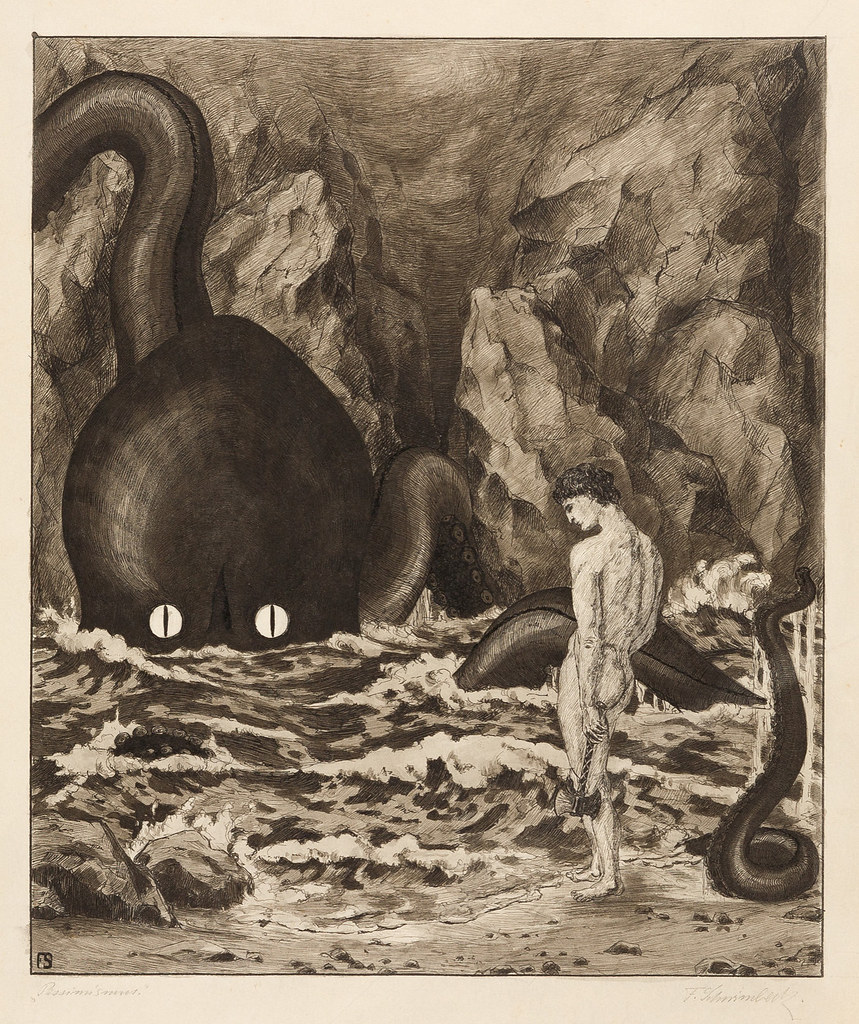

Artwork found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Original Roleplaying Concepts

Artwork found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Artwork found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.  Fear’s Sharp Little Needles: Twenty-Six Hunting Forays into Horror is an anthology of scenarios published by Stygian Fox for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. Published following a successful Kickstarterter campaign, it follows on from the highly-regarded Things We Leave Behind in being set in the modern day, in dealing with mature themes, and in containing contributions from a number of tried-and-tested scenario authors from the last decade or so. What sets it apart though, is that Fear’s Sharp Little Needles contains some twenty-six scenarios, all but one of them, short, sharp stabs of horror—typically each five or six pages in length and thus the length of a magazine scenario or so. All twenty-six can work as one-shots, all but the last can work as convention scenarios, and all but the last require minimum preparation—the latter feature making Fear’s Sharp Little Needles a useful anthology for the Keeper to pull off the shelf at the last minute and have something ready for her gaming group with relatively little effort. In many cases, the scenarios would also work with just the one player and Investigator and the one Keeper. However, with a little more effort, many of the scenarios in the campaign would also work in an ongoing campaign, and in fact, some of them would work with Arc Dream Publishing’s Delta Green: The Role-Playing Game and some of them are actually linked together. Fear’s Sharp Little Needles also has its companion in the form of Aspirations.

Fear’s Sharp Little Needles: Twenty-Six Hunting Forays into Horror is an anthology of scenarios published by Stygian Fox for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. Published following a successful Kickstarterter campaign, it follows on from the highly-regarded Things We Leave Behind in being set in the modern day, in dealing with mature themes, and in containing contributions from a number of tried-and-tested scenario authors from the last decade or so. What sets it apart though, is that Fear’s Sharp Little Needles contains some twenty-six scenarios, all but one of them, short, sharp stabs of horror—typically each five or six pages in length and thus the length of a magazine scenario or so. All twenty-six can work as one-shots, all but the last can work as convention scenarios, and all but the last require minimum preparation—the latter feature making Fear’s Sharp Little Needles a useful anthology for the Keeper to pull off the shelf at the last minute and have something ready for her gaming group with relatively little effort. In many cases, the scenarios would also work with just the one player and Investigator and the one Keeper. However, with a little more effort, many of the scenarios in the campaign would also work in an ongoing campaign, and in fact, some of them would work with Arc Dream Publishing’s Delta Green: The Role-Playing Game and some of them are actually linked together. Fear’s Sharp Little Needles also has its companion in the form of Aspirations.Aspirations – A Modern Day Call of Cthulhu Supplement for Fear’s Sharp Little Needles differs from Fear’s Sharp Little Needles in that it is not just a collection of scenarios. It includes both scenarios and articles, adding extra mysteries and strange situations to be investigated, a potential patron, and more, all for the Modern Day. As with Fear’s Sharp Little Needles, each of the nine entries in the anthology is quite short, no more than seven pages in length, but typically four pages in length. All nine are fully illustrated and many of them come with maps too. The anthology opens with ‘All for a Good Cause’ by Jeffrey Moeller. This presents a potential patron for the Investigators, a Hollywood-based charitable organisation, The Barry Crawford Trust. Named for a now dead actor renowned for his hedonism, it is run by his wife, an adult entertainment actress, and has a secret agenda all of its own—its head hates the Mythos! The foundation will secretly fund investigations into strange mysteries and Mythos activities, and even help out with legal fees and help when the authorities are alerted to the Investigators’ inquiries. All that the foundation asks in return is that they hand over any Mythos artefacts and tomes for destruction. However, their contact seems just a little twitchy, and there is more going on here, nicely hinted at with the illustrations which the Investigators might be able to find and so double as handouts, but what ‘All for a Good Cause’ provides is a ready-made patron and the basis of an over-arching narrative structure into which the Keeper can run any modern-set Call of Cthulhu scenario, whether from elsewhere in Aspirations or Fear’s Sharp Little Needles, or indeed, any modern-set campaign.

Jeffrey Moeller follows ‘All for a Good Cause’ with ‘The Blackthorns’. This details Fair Oaks, a popular and highly regarded suburb—easily located to a town or city of the Keeper’s choice—which hides its dark secret behind its obvious idyllic. It suffers from a rash of disappearances, especially child disappearances. Two weeks ago, another boy disappeared, whilst another boy was found unconscious. If the Keeper is using The Barry Crawford Trust as a patron, the foundation sends the Investigators to the suburb to look into the disappearances, suggesting a potential supernatural link to them. Alternatively, the Investigators might be hired as Private Investigators by the parents of the missing boy. The is some delicacy required here, since it does involve children, but the investigation does present an interesting moral twist upon the Mythos, and in a long-term campaign, that twist might just be too compelling for an Investigator or two. Certainly the Keeper is encouraged to review their actions in past scenarios and campaigns.

Adam Gauntlett provides three entries in Aspirations. The first of these is ‘Dead Mall’, set in and around the dying Diamond Arcade mall in New England, where a blogger charting the region’s dying mall was found dead in the car park of hypothermia on an otherwise warm night. Investigation reveals that the mall is located on site which has been beset by lethally cold weather in the past, so could this death be connected? ‘Dead Mall’ is a short investigation, clues quickly pointing to one of the facility operators in the mall itself. It is likely that the investigation will end in a confrontation and turn physical, so the Investigators will need to be prepared. If using The Barry Crawford Trust, the Investigators’ contact will suggest that witchcraft might be involved.

‘Dead Mall’ is followed by ‘Granny’s Tales’. Rather than a mini-scenario, this details a Mythos tome, but one unlike the traditional ‘bound in unknown leather’, battered, and deeply annotated volume typically beloved of Call of Cthulhu. Granny’s Tales is a seventies adult underground comic, one inspired by artist R. Crumb before it goes off in its own Mythos-inspired direction. Consisting of twelve issues, the early issues are easy to find, but the last one is almost never seen for sale. There are echoes of The Revelations of Gla’aki in Granny’s Tales, in format if not content, and this Mythos tome is nicely detailed and ready to add to a Keeper’s campaign.

The third entry from Adam Gauntlett is ‘The Bay of Nouadhibou’. Again, this is different in being a set-up rather than a full scenario. It will take the Investigators to the Islamic Republic of Mauritania in West Africa where there have been reports of a radical cult operating in the derelicts of the ship graveyard off the city of Nouadhibou. With its mix of religious militantism, slave gangs, immigrant transfers, and Mythos activity on the edge of the Sahara desert, ‘The Bay of Nouadhibou’ is the most suitable entry in Aspirations to use with Delta Green: The Role-Playing Game and it is a pity that this runs to just four pages, as it deserves to be developed into a fuller scenario all of its own.

In Jo Kreil’s ‘Bring Me Your Sick’, William Northfield is dying of cancer and in his search for a cure has begun attending and donating large amounts of money to a health spa where he has been receiving surprisingly effective treatment from its owner, Doctor Baum. The Investigators might be hired by one of Northfield’s relatives or the Board of Directors of his company, either being concerned at the time and wealth that he is pouring into the health spa. The Investigators may benefit having a scientist or doctor involved, or least have one as a contact, but very quickly their enquiries point towards the clinic and a terrible confrontation with Doctor Baum and exactly what he is planning.

Where ‘Granny’s Tales’ detailed a Mythos tome, ‘The Treader of the Stars’ by Brian M. Sammons and Glynn Owen Barrass describes an Alien entity previously presented in their short story, ‘Fall of Empire’ from the Steampunk Cthulhu anthology published by Chaosium, Inc. On the rare occasions it turns its extradimensional attention to earth it whispers secrets into the minds of its cultists who in return build it a body of flesh—from any source. Including mass murder. Once brought to Earth, it enjoys our dimension, causing chaos and rending reality before disappearing again. Along with full stats, the entity is given a detailed description of what it looks like and what it is capable of, which is quite a lot. However, it is not accompanied by any suggestions as to how to use it or scenario hooks, so of all the content in Aspirations, this is not the most immediate of use, or indeed, the easiest

Simon Yee’s ‘Urban Pentimento’ adds another location, this time Japan. This describes Unsu City, a small town which stands in the shadow of Hiroshima and whose secrets are tied into events at the end of World War Two. The town has not just a strange history, but also a Christian of a strange denomination, a satellite office for a German computer company, ghosts lingering from World War Two in the hospital, and a literally underground nightlife… This is a setting waiting for a plot to be developed around it and to it, so will need some development upon the part of the Keeper. It could also have benefited from a map or two.

Rounding out Aspirations is ‘The Lumber Barons’ Ball’ by Chitin Proctor with John Shimmin. This is very much more of a scenario and is very modern in that it involves Kickstarter! Brian Carr successfully funded the first part of his twenties-set horror web comic, Carcosa, on Kickstarter and the second part has been chosen as a Kickstarter Staff Pick, which means that a new interpretation of the King in Yellow will probably be reaching a wider audience. If The Barry Crawford Trust is their patron, then the Investigators will definitely be pointed towards preventing such an occurrence. As well potentially tying in a lost typeface into the Mythos, the scenario provides some solid investigation which the Investigators can do from home before trying to locate Carr at his home in Muskegon, Michigan. Here the investigation is more physical as the Investigators have the opportunity to stay in the converted apartment house and explore the rest of the building as AirBnB guests. The finale takes on the grand affair typical of a scenario involving the King in Yellow, but injects an extra degree of menace and topicality by fronting it as a protest against police shootings. This adds a feeling of freshness to the otherwise decaying and decadent whole affair. Overall, ‘The Lumber Barons’ Ball’ brings Aspirations to a pleasing finish, though some of the content is a little dense and will careful preparation upon the part of the Keeper, and again, it could have done with an extra map or two.

Physically, Aspirations is a slim book, but neatly and tidily presented in full colour with plenty of illustrations and decent maps. In some cases, though, the Keeper will need to provide extra maps herself.

As a companion to Fear’s Sharp Little Needles: Twenty-Six Hunting Forays into Horror, the truth is that Aspirations is not essential. Its content is extra and does not add to or develop the content to be found in Fear’s Little Needles. In some ways, that is a pity. Perhaps The Barry Crawford Trust presented in ‘All for a Good Cause’ could have been expanded to cover how it might involve the Investigators in each of the scenarios in Fear’s Little Needles—or at least those which would have been appropriate. As it is, Aspirations leaves the Keeper to do that and as a result is very much a mixed bag, feeling a little too much like the things that there was no room for in Fear’s Sharp Little Needles. That is, a decent handful of scenarios, one or two settings or ideas begging for richer development, and some needing development upon the part of the Keeper to be truly useful or usable. Overall, Aspirations – A Modern Day Call of Cthulhu Supplement for Fear’s Sharp Little Needles is more an anthology for the completist than a must-have.

Closing on one of the last of the named mythos for One Man's God. I go to one that has a lot of importance for the creation of the D&D, the Nehwon Mythos of Fritz Leiber's Lankhmar series.

You can now get Lankhmar RPG products for both 1st and 2nd AD&D as well as for Savage Worlds and Dungeon Crawl Classics. To say it has left its mark on our hobby is a bit of an understatement. Yet I find I really know very little about the stories. I remember reading one of the books. It was either in late high school or my early college days, in either case, it was the mid-late 80s. I recall reading the book and not really caring for the characters all that much. I have been planning to reread them someday, but they keep getting pushed lower and lower on my to-be-read pile.

For this reason I had considered not doing these for One Man's God. But the more I thought about it the more I realized it was a perfect chance to "level-set" what I am doing here. Seeing if another culture's god can be redefined as AD&D Monster Manual Demon.

Now I am certain that others with far more knowledge than me will have opinions one way or the other and that is fine. They are welcome to share them. A key factor of "One Man's God" is just that, one man's opinion on the gods. And that one man is me.

So strap on a long sword and dirk and let's head to the City of Lankhmar.

Nehwon and Lankhmar in particular seems to have a lot of Gods. I kind of lank this to be honest. But how many of them are "Demons?"

We know there are demons here. Demons and witches are described as living in the wastes. The wizard Sheelba of the Eyeless Face is said to be so horrible that even demons run from it.

Astral Wolves

These guys are great! Love the idea, but they feel more like undead to me.

Gods of Trouble

Ok, these guys start to fit the bill. They are semi-unique, chaotic-evil, and have 366 hp. But they also have a lot of powers that demons just don't have. They have worshipers, but no indication that any spells (for clerics) or powers (for warlocks) are granted. They just seem to be powerful assholes.

Leviathan

There is a demon Leviathan and this guy looks a lot like him. But this one is neutral and does not have any other powers except for being huge.

Nehwon Earth God

This guy appears to be an actual god, even if evil and non-human.

Rat God

AH! Now we are getting someplace. Non-human, cult-like worshipers, described as the manifestation of men's fears, and chaotic evil. I see no reason why the Rat God here could not be a type of demon with a larger power base. At 222 hp he is actually pretty close to Demongorgon's hp.

The Rat God has some personal relevance for me. I was riding the bus home in high school one day and there was a group of kids that were playing D&D. I listened in and guess in their game if you wanted to make boots that aided in your ability to move silently they had to be made from the pelt of the Rat God! I always wondered what their other games must be like.

Rat Demon (Prince of Rats)

Rat Demon (Prince of Rats)FREQUENCY: Very Rare

NO. APPEARING: 1

ARMOR CLASS: 2

MOVE: 18'

HIT DICE: 222 hit points

% IN LAIR: 50%

TREASURE TYPE: P, S, T

NO. OF ATTACKS: 2

DAMAGE/ATTACK: 4-40

SPECIAL ATTACKS: Nil

SPECIAL DEFENSES: See below

MAGIC RESISTANCE: 20%

INTELLIGENCE: Supra genius (18)

ALIGNMENT: Chaotic Evil

SIZE: L (10' tall)

PSIONIC ABILITY: I

The Demon Prince of Rats is nearly powerful as other demon princes but he saves his interests and attention only for his rat and wererat followers. He desires to overrun the Prime Material Plane with his children and feed on the bodies of all the living.

Spider God

Same is true for this one. I mean if rats are a manifestation of human fears then spiders are as well. This creature is also CE and at 249 hp that makes it more powerful than Lolth at 66!

Tyaa

Could be a demon, but had more goddess about her. Again though, Lolth is both Goddess and Demon. We will later get a demoness of birds in D&D during the 3e days in the form of Decarabia. Tyaa requires her cult to sacrifice a body part, Decarabia cut off her own legs so she would never touch the ground again.

Bird Goddesses and Demoness, separated at birth?

Bird Goddesses and Demoness, separated at birth?Obviously there a lot more here that could be done with these and the monsters/gods/demons that were not featured in the D&DG.

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Younger - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Younger - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Circle of Jan Breughel the Younger - The Underworld

Circle of Jan Breughel the Younger - The Underworld

Circle of Jan Breughel the Younger - The Descent into Hell, 1601-78

Circle of Jan Breughel the Younger - The Descent into Hell, 1601-78

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Younger - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Younger - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Follower of Jan Breughel - The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 17th C

Follower of Jan Breughel - The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 17th C

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 16th-17th C

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 16th-17th C

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - Juno's Arrival in Hades, circa 1598

Follower of Jan Brueghel the Elder - Juno's Arrival in Hades, circa 1598

Image sources include Sotheby's.

Jan Brueghel the Elder's paintings were previously shared here.

The Dream, 1909

The Dream, 1909  The Dream of the Semiramis, 1909

The Dream of the Semiramis, 1909  My Dream, My Nightmare, 1909

My Dream, My Nightmare, 1909  Figure in the Mountains, 1920

Figure in the Mountains, 1920  Eternity, 1910

Eternity, 1910  Pessimism, 1910

Pessimism, 1910  Dracula, 1917

Dracula, 1917  Dracula, 1917

Dracula, 1917  A Deam From G. Meyerink, 1917

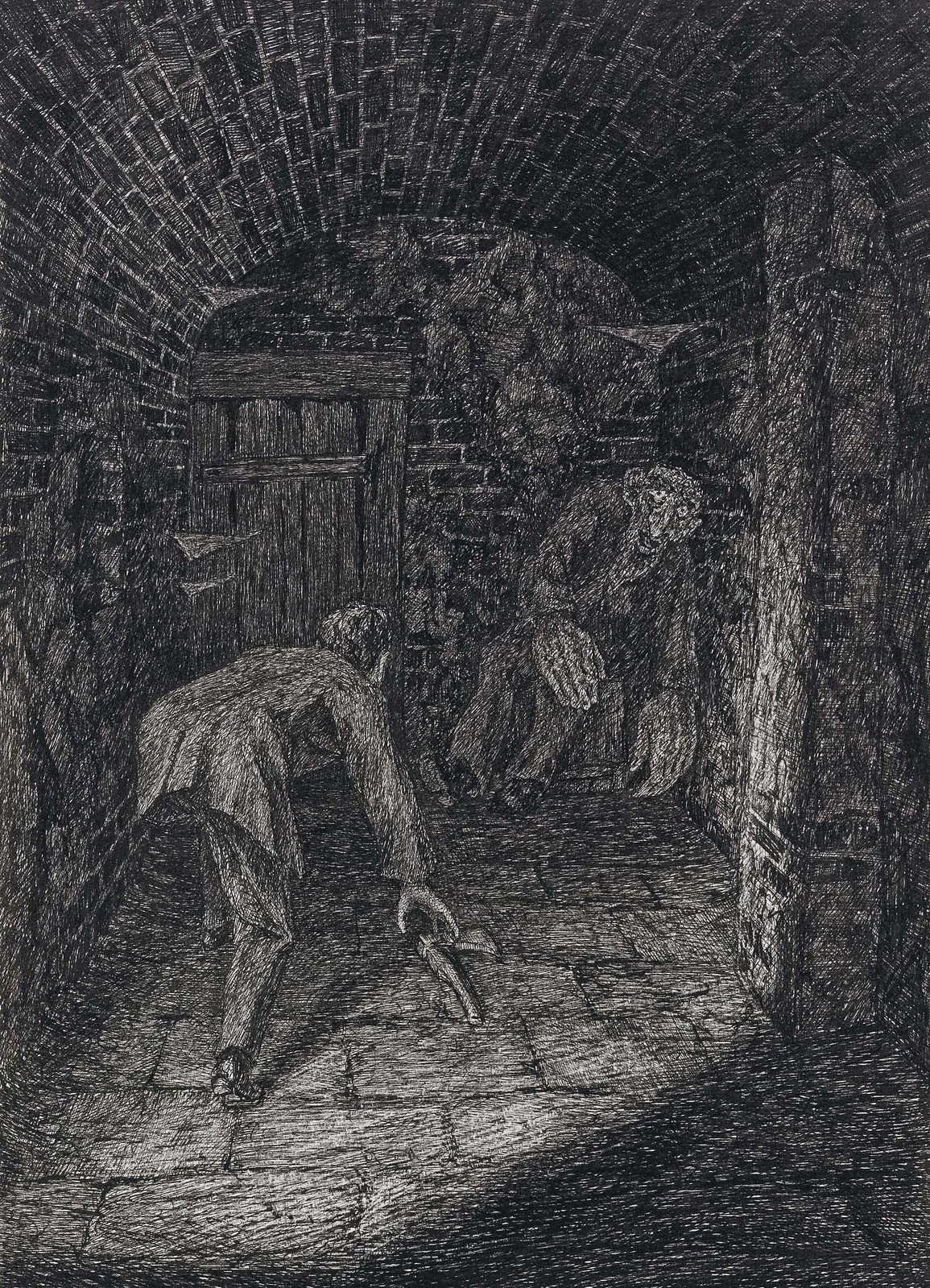

A Deam From G. Meyerink, 1917  In the Vault, 1920

In the Vault, 1920  The Elemental Spirit, 1917

The Elemental Spirit, 1917  Entrance of the Fish Frogs, 1919

Entrance of the Fish Frogs, 1919  Ghost on the Stairs

Ghost on the Stairs  Laponder, 1916

Laponder, 1916  The Fish Hook, 1915

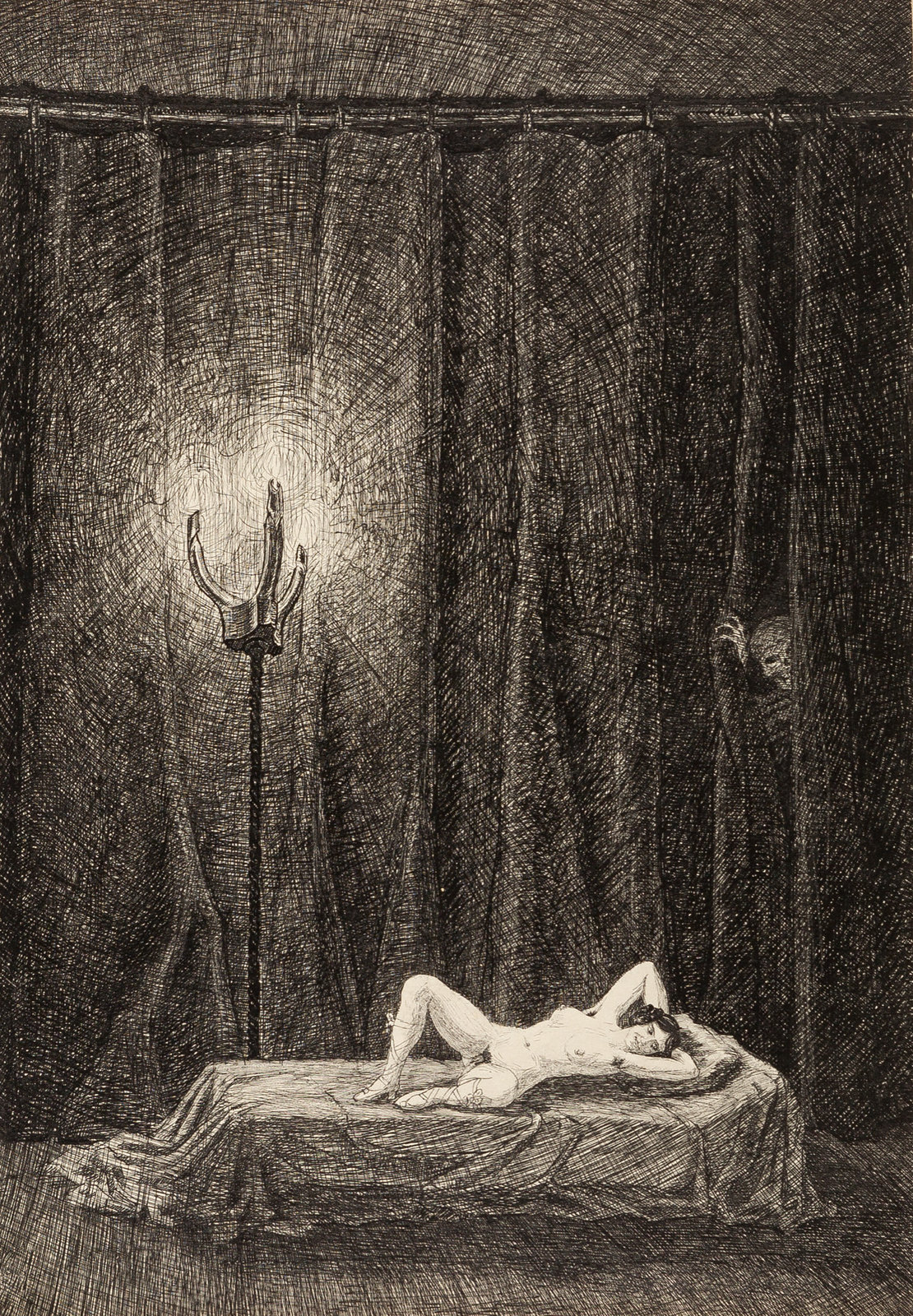

The Fish Hook, 1915  Consecration, 1917

Consecration, 1917  Drive, 1917

Drive, 1917  Angst, Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917

Angst, Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917  Doppelganger, 1919

Doppelganger, 1919  The Shadows, 1919

The Shadows, 1919  Golem - Spook, 1916

Golem - Spook, 1916  Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917

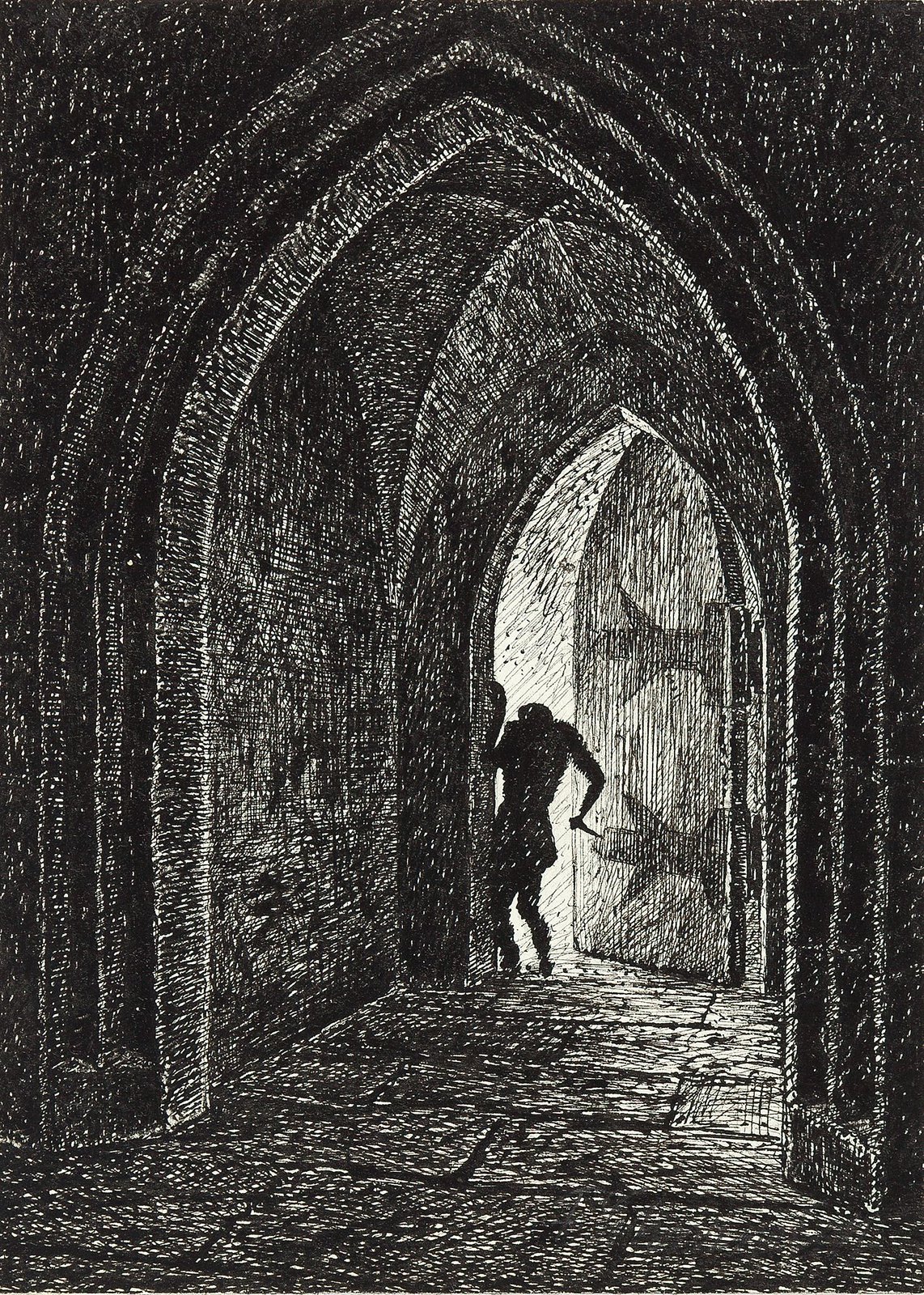

Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917  Golem, Dark Corridors

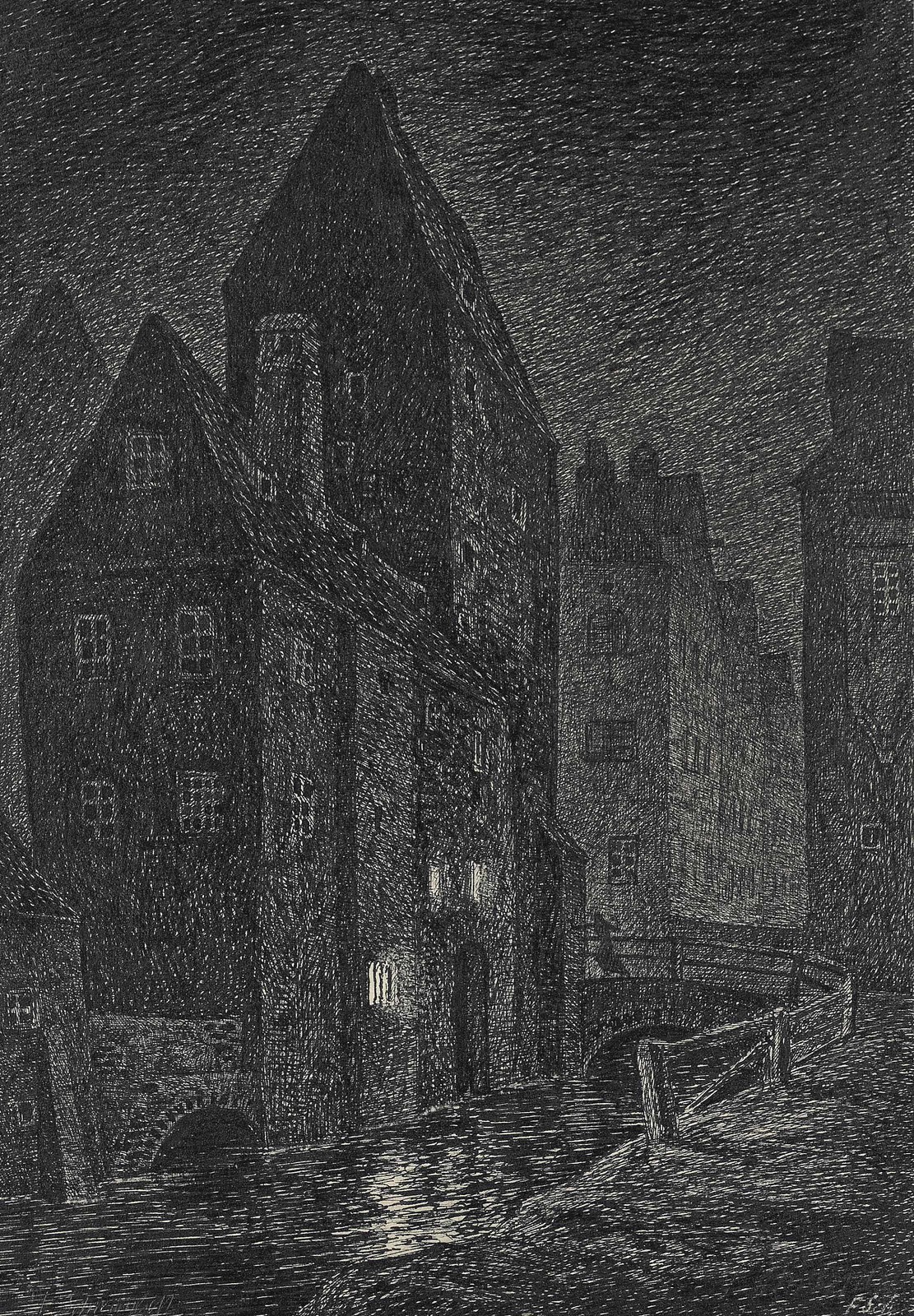

Golem, Dark Corridors  Night, Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917

Night, Original draft for "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917  Sketch for Macbeth, The Dagger, 1919–1920

Sketch for Macbeth, The Dagger, 1919–1920  In the passage, Original draft of "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917

In the passage, Original draft of "The Green Face" by G. Meyrink, Verlag G. Müller, 1917  Rocky landscape, 1920

Rocky landscape, 1920  Fantasies About An Old House, 1917

Fantasies About An Old House, 1917  Untitled, 1917

Untitled, 1917  Torture Tower, 1919

Torture Tower, 1919  Fantasies About an Old House

Fantasies About an Old House  Untitled

Untitled  Untitled

Untitled  Macbeth, 1914

Macbeth, 1914 The word is out that next D&D book/campaign setting is going to be Ravenloft and I could not be more pleased!

What do we know so far?

It will be released on May 18th, 2021 and it has both the normal and game store exclusive covers. I have already preordered both.

Thirty Domains of Dread will be detailed. These include Lamordia, Dementlieu (both from the original 2nd Ed set), Kalakeri (new), and Falkovnia (revised).

Likewise, we are getting old, new, and revised Darklords. One that seems to be causing a stir is Dr. Viktra Mordenheim and her creation Alyss. Not sure if she is a genderswapped Viktor, a daughter or something else. I mean, lets be honest, even Hammer did the wives and daughters of all their great movies. Ravenloft can too.

Gothic Horror will be covered as well as more traditional "ghost" stories, psychological horror, dark fantasy, and D&D's own brand of cosmic horror. Which is good, I love all that Far Realm stuff.

While the book is called "Van Richten's Guide" the eponymous Van Righten disappeared before he could complete his last volume "Van Richten's Guide to Witches." So I am expecting, and am promised, new monster hunters to carry on his legacy. Our cover girl appears to be Ezmerelda d’Avenir, one of the newer vampire hunters in Barovia.

There are two new sub-classes, College of Spirits Bard and the Undead Pact Warlock.

For lineages, there are dhampir, hexblood, or reborn characters, which offer vampire, hag, and undead lineages, respectively.

Characters can also get "dark gifts" to aid them in their fights...or to help them become the monster they truly want to be.

There will be 40 pages on monsters; some new and some familiar ones. I am expecting to see a Brain in the Jar myself.

And a new adventure. A new take on the House of Lament.

It also sounds like they have a wide variety of voices and inputs on this which is great; horror is a universal concept. Many are horror authors. I while I do love my Gothic Horror, I also love all horror. I am looking forward to seeing the Vistani become something more than an uncomfortable stereotype.

So folks are complaining about the "loss" of Falkovnia, but's let's be honest here. Falkovnia and Vlad Drakov were nothing more than the "leftovers" after Barovia and Strahd mined all the Dracula lore. I never even used it much back in the 2e days and I am certainly not missing it now. Falkovnia is now a zombie apocalypse land and I think that works better to be honest. We didn't really have one of those.

Sithicus may or may not show up, but Lord Soth certainly won't. Also not a surprise really. Those rights were a tangled mess anyway.

I am rather looking forward to this book. Ravenloft was MY game for all of 2nd Ed AD&D and college. I bought every campaign book, adventure, and yes even novel I could get my hands on. I was contributing to the Kargatane official netbooks of Ravenloft material. My 2nd Ed AD&D is Ravenloft; I don't separate the two.

My only question is do I put this on my D&D5 shelf, my horror shelf, or my Ravenloft shelf?

Links

Well. Not actually, but I am considering completely redoing all the Outer Planes in my D&D-like games, and the lower planes in particular.

My goal here is to restructure it is such a way that it works better for me and what I am doing in my games, and yet still be compatible enough with other iterations of the game, de that original game, OSR, or other OGL sources, that I can grab something off the shelf and make it work.

Over the years I have talked about Hell, the Abyss, and other places such as Xibalba, Tartarus, and Tehom. Pathfinder has added some of these realms into OGC, or rather have made SRD connections to Public Domain names (like Abaddon).

I would also like to work in places like Sheol as well and homes for all the demon species I have been working on.

Hell

Hell of the D&D universe is much more akin to the ideas of Hell from Greek myths, Dante, and Milton than it is from Judeo-Christian sources. There are some ideas here from other myths as well.

According to Dante, the main named devil in Hell is Lucifer/Satan. He also mentions Geryon and names 12 individual Malebranche devils ("evil-claws") on Hell's eighth level, called here Malbolge.

According to Milton, the main devils are Beelzebub, Belial, Mammon, Moloch, and Satan. But on his way to Hell, possibly when he passes through Night and Chaos, are Orcus, Demogorgon, and Hades.

One of the first things I need to do is at least come up with some names for the Nine Circles / Nine Layers of Hell. At least most people agree on nine.

Layer Name (D&D) Name (Pathfinder) Name (Dante)* Deadly Sin (Dante) 1 Avernus Avernus Limbo Virtuous Pagans 2 Dis DisI can't use the "D&D Column" with an OGL/OGC book, but the "Pathfinder" one is fine. Well. It is fine, but lacks something for me. For now though I am going to use these.

*City of Pandæmonium

From Milton (Not Dante). This is the great city in the lowest circle of Hell. I am certainly going to use this.

Once I get my layers worked out I'll need to figure out who rules them. The current (and some former) rulers are here. Using D&D layer names.

Layer Name Archdevil Deadly Sin (Mine) 1 Avernus Druaga/Tiamat/Bel/Zariel * 2 Dis Dispater Envy 3 Minauros Mammon Greed 4 Phlegethos Belial/Fierna Sloth 5 Stygia Geryon/Levistus Wrath 6 Malbolge Beherit/Moloch/Malagard/Glasya Lust 7 Maladomini Baalzebul/Beelzebub Gluttony 8 Cainia Mephistopheles Pride 9 Nessus Asmodeus *I do like the idea of aligning Lord/Layer with a Deadly Sin.

Now, not all of these Archdevils are OGC, and frankly I would rather use one of the Ars Goetia demons as the rulers. In other cases, I am making changes. Tiamat is a Chaotic Evil "Eodemon" in my games. Geryon is also now a "rage demon." Druaga, or maybe now just Druj, will also be something else.

At the moment I have about 650 demons and devils detailed for my Basic Bestiary II but none are sorted or detailed beyond basic descriptions. I need to start figuring out who "lives" where.

Links

Artworks found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Artworks found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here is a monster that has been rummaging around in the back of my mind for a while now. I have renewed my search for this creature thanks to getting all caught up on the new "Nancy Drew" series which has a solid supernatural vibe to it.

The word seems to come from Beowulf, but there is a lot of debate over what it means exactly.

We can go to the root word, āglāc, which can mean distress, torment, or misery. It later derived the Middle-English word egleche meaning warlike or brave. The Dictionary of Old English describes it as an awesome opponent, a ferocious fighter. There is so much confusion and speculation on this word there is even a recent Master's Thesis on it, Robinson, Danielle, "The Schizophrenic Warrior: Exploring Aglæca in the Old English Corpus." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015.

Given the Beowulf connection, I did look to the troll connection; I always thought of Grendel as some sort of troll. But I have already done a Troll-wife (a type of hag) and a Trolla (a type of troll witch). There also seems to be a demonic or even diabolic association with this creature. But I have also already done demonic trolls. Given the Old-English and Middle-English sources of the word I even thought that something along the lines of a proto-hag might work, but I have done those as well in the Ur-hag.

Robinson details some comments from Tolkien on his reading of Beowulf and spends time talking about the monster (and true to her thesis, the noble warriors) that appear in the poem.

Both Grendel and his mother are described as aglæca. While I like to think of Grendel as a troll and his mother as more of a troll-wife, maybe there is more to it.

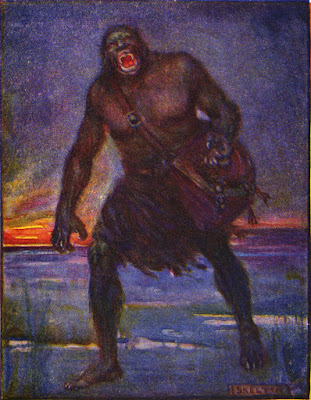

Grendel by Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton

Grendel by Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton

Aglæca

Large Humanoid

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1)

Alignment: Chaotic [Chaotic Evil]

Movement: 180' (60') [18"]

Armor Class: 4 [15]

Hit Dice: 8d8**+16 (52 hp)

HD (Large): 8d10**+16 (60 hp)

Attacks: claw, claw, bite

Damage: 1d6+4 x2, 1d8+4

Special: Cause fear, magic required to hit, regenerate 1 hp per round, infravision, sunlight sensitivity.

Size: Large

Save: Monster 8

Morale: 12 (12)

Treasure Hoard Class: XIX [D] x2

XP: 1,750 (OSE) 1,840 (LL)

The aglæca is a large humanoid creature that appears to be something of a mix of both ogre and troll. It is blue-ish grey in color with patches of dark blue that are the color of bruises. It smells of rotting meat, decay, and the sea. Its long muscular arms end in large hands with great claws. Its mouth has large fangs and tusks and maybe most disturbingly, its eyes burn with a fierce intelligence.

It is believed to be a descendant of the great giants and Jötunns of the north and the ancestor to the more common ogre and troll. Some scholars speculate that there is a bit of demonic blood in this creature, or even something more evil and primal.

The aglæca causes fear (as per the magic-user spell cause fear) to any that sees it. It will use this power to fearlessly attack opponents. It will use its claws and bite in an attack. While it is intelligent and knows the value of weapons in combat, its berserker-like fury will cause it to abandon weapons in favor of its own hands. The aglæca will take anything it kills back to their caves to eat. Their preferred food is humans followed by elves, halflings, and dwarves.

Only magic weapons or magic can hit it and it can regenerate 1 hp per round. The aglæca prefers to fight at night or in the dark. It attacks at -1 in light and at -2 in bright sunlight. Aglæca speaks the local languages and giant. They are fearless in battle.

The origins of the aglæca are a mystery. It is speculated that they are very, very old creatures. Thankfully they are very rare and getting rarer to find all the time.

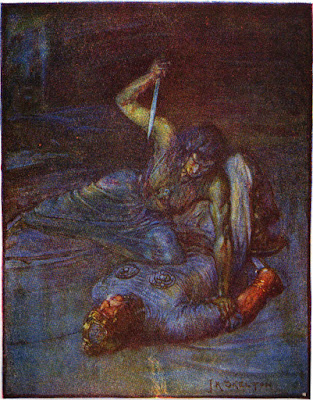

Grendel's Mother by Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton

Grendel's Mother by Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton

Aglæc-wif

Medium Humanoid

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1)

Alignment: Chaotic [Lawful Evil]

Movement: 180' (60') [18"]

Swim: 180' (60') [18"]

Armor Class: 4 [15]

Hit Dice: 6d8**+12 (39 hp)

Attacks: claw, claw, bite

Damage: 1d6+3 x2, 1d8+3

Special: Cause fear, magic required to hit, regenerate 1 hp per round, infravision, witch magic.

Size: Medium

Save: Monster 6

Morale: 12 (12)

Treasure Hoard Class: XIX [D] x2

XP: 1,250 (OSE) 1,280 (LL)

The aglæc-wif is the smaller female of the aglæca species. It is conjectured that there may in fact be larger female aglæca that are not aglæc-wif and the aglæc-wif might be another related creature. So far the only aglæc-wif that have been recorded have been a pair with a larger aglæca.

Like the aglæca, the aglæc-wif appears to be related to the troll and/or ogres. They also are quite intelligent and while they are perfectly happy to murder and eat any human they see, they are not just ravenous monsters. The aglæc-wif also possesses the infravision of the aglæca but is not hampered by light or sunlight. Also, like the aglæca, these creatures feed on humanoids, but they prefer humans to all other forms of food.

An aglæc-wif can attack with claws and bite like the aglæca, but she is also capable of using spells as a 4th level witch of the faerie, sea, or winter traditions. Their preferred spells are charm-based. Any magic that provided protection from or special damage to Sea Hags is also effective on an aglæc-wif.

It is speculated that like a troll-wife the aglæc-wif can join a covey of hags as a third hag. Though none have ever been reported as doing so.

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

Name: Hand of Glory

Name: Hand of Glory

The artwork is on display at Musée du Luxembourg.

The artwork is on display at Musée du Luxembourg.  Imagine a roleplaying game which gives you two hundred pages of character options. Imagine a roleplaying game with a large expansive setting. Imagine a roleplaying game which builds the details of its setting from its character options—all two hundred pages of them. Imagine that Player Character generation in such a roleplaying game—with all two hundred pages of its options would take a mere five minutes. Actually less. Imagine a roleplaying game in which the Player Characters are adventurers and treasure hunters across this large expansive setting. Imagine that such a roleplaying game has Old School Renaissance sensibilities in terms of its simple mechanics—simple mechanics which are explained in four pages—and the dauntingly dangerous nature of its world. Combine all of these aspects together and what you have is Electric Bastionland, a roleplaying game of failed careers, debt and treasure hunting, and exploration and survival, across, under, and beyond a vast metropolis which is created and improvised through play and from tables.

Imagine a roleplaying game which gives you two hundred pages of character options. Imagine a roleplaying game with a large expansive setting. Imagine a roleplaying game which builds the details of its setting from its character options—all two hundred pages of them. Imagine that Player Character generation in such a roleplaying game—with all two hundred pages of its options would take a mere five minutes. Actually less. Imagine a roleplaying game in which the Player Characters are adventurers and treasure hunters across this large expansive setting. Imagine that such a roleplaying game has Old School Renaissance sensibilities in terms of its simple mechanics—simple mechanics which are explained in four pages—and the dauntingly dangerous nature of its world. Combine all of these aspects together and what you have is Electric Bastionland, a roleplaying game of failed careers, debt and treasure hunting, and exploration and survival, across, under, and beyond a vast metropolis which is created and improvised through play and from tables. As the Kickstarter for The One Ring Roleplaying Game, Second Edition continues apace, one of the most interesting additions to the new version is that of a Starter Set. Now The One Ring, originally published by Cubicle Seven Entertainment never actually did not receive a Starter Set, but publisher of the forthcoming second edition, Free League Publishing has an interesting track record with both the Alien Starter Set for the Aliens Adventure Game and the Tales from the Loop Starter Set for Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the ’80s That Never Was—and the forthcoming The One Ring Starter Set looks interesting. If Cubicle Seven Entertainment did not publish a Starter Set, then what it did publish was Bree. Instead of a Starter Set, what Bree can be best described as is a starting supplement.

As the Kickstarter for The One Ring Roleplaying Game, Second Edition continues apace, one of the most interesting additions to the new version is that of a Starter Set. Now The One Ring, originally published by Cubicle Seven Entertainment never actually did not receive a Starter Set, but publisher of the forthcoming second edition, Free League Publishing has an interesting track record with both the Alien Starter Set for the Aliens Adventure Game and the Tales from the Loop Starter Set for Tales from the Loop – Roleplaying in the ’80s That Never Was—and the forthcoming The One Ring Starter Set looks interesting. If Cubicle Seven Entertainment did not publish a Starter Set, then what it did publish was Bree. Instead of a Starter Set, what Bree can be best described as is a starting supplement.Although this is not a starter set, it is focused on a smaller area and its three scenarios are designed for beginning Player Characters. It takes The One Ring further west from the Misty Mountains, Rivendell, and Eriador, and can serve as both an expansion to that supplement and region, both in terms of its description of the village of Bree and its immediate environs. And then, the three scenarios presented in Bree could easily be added to those set in Eastern Eriador, as detailed as in Ruins of the North. Alternatively, the Loremaster can use the content and scenarios in Bree as an introduction to The One Ring for both the players and their characters, and then go on to explore the wider area and undertake the scenarios set there with Rivendell and Ruins of the North. Essentially, come west from Rivendell with experienced Player Characters or go east from Bree with new ones. With established Player Characters, they could be of any Heroic Culture, but for new ones, it is intimated that players select either Hobbits of the Shire, Men of Bree, Bree-Hobbits, and perhaps the odd Dwarf Heroic Cultures for their Player Characters. This will serve to keep some of the mystery of the wider world to be revealed through the three scenarios in Bree and then on to Rivendell and Ruins of the North. This option would also work well with the forthcoming The One Ring Starter Set from Free League Publishing which focuses on The Shire, so the Hobbits who have had adventures in their homeland, can have their next in and around Bree.

Bree presents Bree-land and its four constituent villages—Archet, Combe, Staddle, and of course Bree for The One Ring. In character, despite the number of traders passing through Bree itself, the village and area is conservative, its inhabitants, both the Men of Bree and the Hobbits of Bree, its Big Folk and Little Folk, sensible and not given to adventures and wild doings. Those that are, of course, are deeply frowned upon, because there is just not something right about them. There is relatively little history to Bree and Bree-land, the village having stood at the crossroads of the Greenway which runs north into a land of dark hills and ruins and south towards the Gap of Rohan, and the East Road which runs from the Misty Mountains in the east to the Shire in the west, for many centuries. It is a bastion of quiet civilisation beyond which lies wilderness and danger, which mostly obviously relies upon the Bree-Wardens and their big sticks and the ancient hedge which encircles the village of Bree for its protection, but the reality is that neither could truly withstand a concerted effort by a force of Orcs or the influence of the Shadow… Thus, at the direction of Gandalf the Grey, the Rangers of the North undertake the duty to protect both Bree and Bree-land, though few Bree-landers realise it and most distrust any Ranger they see.

All four villages of Bree-land are described in some detail, though only Bree is given a map of its own. Understandably, The Prancing Pony, perhaps the most famous inn in all of Middle Earth is described in detail, as the owner, Barnabus Butterbur—the forgetful Barliman is his son—and full plans of the building are provided as is a table of encounters. The Prancing Pony is likely to be the focal point of most of the Player Characters when in Bree, but the supplement suggests several new activities which members of a Fellowship can conduct during the Fellowship Phase. The first is Opening Bree as a Sanctuary—though Bree is so small that the Fellowship will need to earn the trust of Bree’s important personalities and of the Rangers, and become regulars at The Prancing Pony. The others include Guard the East Road, Building the Refuge at Girdley Island—the latter to better support Ranger missions in the area; Write a Letter—this needs to be delivered, but can inform the recipient of the author’s arrival, ask for aid, arrange a meeting, and more; have a Chance-Meeting in the Inn; and more.

Bree adds one new Heroic Culture and makes alterations to a second. The former is Men of Bree, which enables players to create characters from Bree-land with one of six Backgrounds, as per other Heroic Cultures in The One Ring. They include a character having been away to the Blue Mountains as a caravan guard, serving as a Gate-warden, and having become aware of the presence of the Rangers in and around Bree-land. The Heroic Culture captures the sheltered nature and upbringing of the Bree-landers. For Bree-Hobbits, the supplement mixes elements of the Men of Bree and Hobbit of the Shire Heroic Cultures.

Although there are suggestions as to adventuring in and around Bree, the supplement comes with three scenarios which take place over the course of two to three years. They can take place in any year, but the supplement suggests that the first, ‘Old Bones and Skin’ takes place in the autumn of 2950, then the second, ‘Strange Men, Strange Roads’, the summer of 2951, and the third, ‘Holed Up in Staddle’, in the autumn of 2951. The scenarios could be run separately, but really work together as a trilogy which forms a mini-campaign. Each is nicely set up with an explanation as to when, where, what, why, and who before breaking the scenario down into easy parts. All three scenarios are relatively lengthy, and should take two to three sessions to complete.

The first scenario is ‘Old Bones and Skin’, which is in part inspired by a song by Sam Gamgee. It opens amidst a scandal, young Tomas Heatherton having failed to attend his uncle’s funeral, but the discussion of scandal is interrupted when the young man rushes into The Prancing Pony, white as a sheet and blathering about a ghost in the graveyard! This is the opportunity for the Player Characters to strike out as heroes for the first time, and lengthy investigation of the graveyard reveals a more corporeal threat—an old Troll! Chasing the Old Troll across the South Downs is a challenging task, but success leads to a trove of treasure—using the rules for treasure from the Rivendell supplement—and revelation of family secrets. These family secrets tie into the plot behind the trilogy, whilst the adventure will see the Player Characters first make a name for themselves. Although the Player Characters will find themselves going up hill and down dale, this adventure is a bit of a romp, in turns exciting and scary, and mysterious.

The second scenario, ‘Strange Men, Strange Roads’ requires a little bit of a set-up, but this gets the Player Characters their first assignment—meet a contact at the Forsaken Inn, a disreputable and unwelcoming stop further along on the East Road. Unfortunately, the contact is found dead and the most likely culprits are amongst a trade caravan heading back to Bree and beyond. Investigating a trade caravan on the move is a challenge and will require a mix of stealth and guile. The Loremaster has a good cast of NPCs to portray—perhaps slightly too many for the Loremaster new to roleplaying—and even as a murder mystery set in Middle Earth, the scenario has echoes of Film Noir. There are some pleasing encounters along the way, not all of them dangerous, and not all of them casting the villains as truly black-hearted. It should all come to a head in the corridors of The Prancing Pony and present the Player Characters with a moral dilemma. If there is an issue with the scenario it is perhaps that the events it sets up happen off screen. Now these could be played out, but would require more experienced Player Characters and the Loremaster to design the situation to be played out. Otherwise, this is another good scenario, one which brings the darkness to found beyond the borders of Bree to within its thick hedge.

The third scenario, ‘Holed Up in Staddle’ takes place entirely in Bree-land and in bringing the trilogy of scenarios in Bree to close, also brings the consequences of the first two scenarios to head as well. The Player Characters come to the aid of the Rangers in tracking down some of the villains, but despite the aid of a notable figure in the area, lose track of them. With no further leads, the Player Characters are forced to return to Bree. There rumour spreads that one of the richer families of Hobbits in nearby Staddle is acting out of the ordinary, its members having become more reclusive and insular than is the norm. Ideally, Player Characters will follow up on this and ferret out an idea or two as what might be going on. The finale of the scenario and the campaign will see them launch an attack on a Hobbit hole! Which will be a challenge for anyone not Hobbit-sized. The scenario is decent enough, but not as satisfying as the first two and it does feel like the authors are in a hurry to get to its climax and that of the campaign.

Overall, the campaign should ready the Player Characters for adventuring in the wider world beyond the borders of Bree-land. The three scenarios are sophisticated and deep and rich, and involve a good mix of tasks and challenges—physical, social, and combat. The campaign has more of a self-contained feel to it, being confined to one small area, but this more readily allows the Loremaster and her players to bring this smaller part of Middle Earth to life and to have the Player Characters invest themselves in it and in protecting it, likely to open up Bree as their first Sanctuary. One thing that the Loremaster will need to do is prepare a list of NPC names for inhabitants of Bree-land that the Player Characters might run into in any one of the villages and thereabouts, as well as for nefarious ne’er-do-wells—like certain members of the Ferny family—and strangers who might take an interest in their activities.

Physically, Bree is a relatively slim book by the standards of supplements for The One Ring. It is a pretty book, done in earthy tones throughout that give it a homely feel that befits the setting of Middle Earth. The illustrations are excellent, the cartography decent, and the writing is clear and easy to understand. It even comes with a good index.

Bree nicely fits onto the realm of Eriador as an expansion to or lead into Rivendell and Ruins of the North, as much danger and mystery as there is presented—and that danger is very well-presented and explained in Bree—there is ultimately a pleasing cosiness and homeliness to both the supplement and the area it describes. Bree is a charming introductory setting for The One Ring and a fantastic stepping stone onto exploring the wider Middle Earth.

It's been a bit since I did a Friday Night Videos, but maybe it's the dark of winter that has my mood looking to some new music from some of my favorite women-fronted bands. And while we are at it let's make this a #FollowFriday too! Follow them all and don't forget to buy their songs, albums, or whatever they have. People have been saying "we don't need artists during this quarantine" and to that I say bullshit! Artists have kept me living in all of this. We need them more than ever.

Let's get into it!

Up first is a favorite of The Other Side, Arden Leigh.

Arden fronted the band Arden and the Wolves. Now she has a new project she is doing Prospertine. Which consists of her and Jeremy Bastard. Their first single is Home.

You can follow her, The Wolves, and Prospertine on the web at:

Arden

Arden and the wolves

Prospertine

Another favorite here is the sister group Neoni. Their newest song Notorious is now out. It has a serious Lorde vibe and I mean that is the best possible way.

Neoni also gave Fandom the gift of covering "Carry On (Wayward Son)" for the Supernatural Series Finale. For this alone they have earned a solid place in geekdom.

You can find and follow Neoni at:

Taylor Momsen of The Pretty Reckless has been putting out some great music for while now. Their newest album, Death by Rock and Roll has a lot of great songs on it. Personal, Taylor is getting better with each album and I have to admit I am pleased she quit acting to do this full time.

Witches Burn grabbed my attention right away.

It's going to be interesting to see where she is in a few years because I think she is just getting better with each album.

Find The Pretty Reckless here:

Speaking of getting better.

Confession time. When they first came out I really didn't care for Evanescence. I mean I recognized that Amy Lee had a powerful voice, but they never connected with me really. Fast forward a few years and I am listening to her doing duets and singing background on other artists' songs and I am just impressed with her. I think she is a better singer now than she was 20 years ago. Here is Evanescence's most recent one and as a bonus Lzzy Hale is singing backup.

You can find Evanescence on the web here:

Check them all out!

Published in 2014, Colt Express is a super fun game of bandits raiding a train in the Wild West, which would go to be the 2015 Spiel des Jahres Winner. From one round to the next, each player programs the actions of bandit and then at end of each round, these actions are played out in order, and as each action happens, the bandits aboard the train interact with each other, plans go awry, and chaos ensues! The fact that this takes place aboard a cardboard model of a train that sits on the table in front of the players and they get to program their bandits’ maneuvres up and down and along the train, only serves to make the game more entertaining. In the years since, Colt Express has been supported by a handful of expansions, such as Colt Express: Horses & Stagecoach, including even a Delorean! However, as good as it looks and as fun as it is to play, Colt Express is at its best when there are players sat round the table and all six bandits are involved, and a game can devolve into maximum chaos and in the space of thirty minutes or so, tales of how each bandit successfully—or unsuccessfully robbed the Colt Express. So, what do you do if there are fewer than six players? Five players is fine, four maybe… With fewer players how do you back up to that maximum fun? Well, publisher Ludonaute has a solution—the Colt Express Bandits series.

The Colt Express Bandits series consists of not one expansion, but six. One for each of the six bandits in Colt Express— Belle, Cheyenne, Django, Doc, Ghost, and Tuco. Each expansion replaces its particular bandit in the game, but not when the bandit is being played by a player. Rather an expansion takes the place of a bandit who is not being controlled by a player and hands that control to the game itself. Each Colt Express: Bandits expansion adds new deck of eight Action cards which will control the bandit from one turn to the next and two special moves or effects.

So, what can each bandit do?

In Colt Express, with a “Liddle ol’ me?”, Belle cannot be targeted by a Fire or Punch action if another Bandit can be targeted instead. In Colt Express Bandits – Belle, her Action cards consist of Move—always towards where there is the most jewels to be picked; Punch—everyone in the same carriage and always towards the back of the train!; Theft—steal a Jewel from every Bandit in the same carriage; Robbery—jewels if she can; and Charm—make all of the Bandits aboard the train move towards her. Lastly, when she encounters the Marshal, she charms him into not shooting her! Belle is all about using her charm to steal as many jewels as she possibly can.

In Colt Express, with a “Liddle ol’ me?”, Belle cannot be targeted by a Fire or Punch action if another Bandit can be targeted instead. In Colt Express Bandits – Belle, her Action cards consist of Move—always towards where there is the most jewels to be picked; Punch—everyone in the same carriage and always towards the back of the train!; Theft—steal a Jewel from every Bandit in the same carriage; Robbery—jewels if she can; and Charm—make all of the Bandits aboard the train move towards her. Lastly, when she encounters the Marshal, she charms him into not shooting her! Belle is all about using her charm to steal as many jewels as she possibly can. In Colt Express, Cheyenne is a pickpocket and when she punches a Bandit, also steals a Purse from her victim. In Colt Express Bandits – Cheyenne, her Action cards consist of a Double Move—two carriages if in the train or four if on the roof, or a Single Move—one carriage if in the train or two if on the roof, and always towards the most Bandits, after which she pickpockets a Purse from a random Bandit in her new location. She also a Bow Attack which replaces her pistol attack, enabling her to fire poisoned arrows at her rivals. These are treated like bullets as in the standard game and clog up a Bandit’s Action Deck. A poisoned Bandit must grab one of the Antidotes—to be found throughout the train—to be consumed per Poisoned Arrow taken. A Bandit who has suffered one or more Poisoned Arrows cannot win the game. Thus, Cheyenne is all about stealing Purses from her rival Bandits and preventing them from winning with her Poisoned Arrows.

In Colt Express, Cheyenne is a pickpocket and when she punches a Bandit, also steals a Purse from her victim. In Colt Express Bandits – Cheyenne, her Action cards consist of a Double Move—two carriages if in the train or four if on the roof, or a Single Move—one carriage if in the train or two if on the roof, and always towards the most Bandits, after which she pickpockets a Purse from a random Bandit in her new location. She also a Bow Attack which replaces her pistol attack, enabling her to fire poisoned arrows at her rivals. These are treated like bullets as in the standard game and clog up a Bandit’s Action Deck. A poisoned Bandit must grab one of the Antidotes—to be found throughout the train—to be consumed per Poisoned Arrow taken. A Bandit who has suffered one or more Poisoned Arrows cannot win the game. Thus, Cheyenne is all about stealing Purses from her rival Bandits and preventing them from winning with her Poisoned Arrows.  In Colt Express, Django is a crackshot and when he shoots another Bandit, he or she is knocked into the next carriage. In Colt Express Bandits – Django, he still has that capability, but here he fires a volley, the bullets hitting the nearest group of Bandits rather than a single Bandit! In addition, at the beginning of the game, each other Bandit receives two Ejection tokens, and at the beginning of each turn, Django places a Dynamite token in the carriage he is currently in if it does not have one. When the Explosion Action card is draw, all of the Bandits caught in the explosions are ejected from the train and must use their next action to reboard the train. Any Bandit ejected from the train in this fashion must give one of their Ejection tokens to Django and these are worth money at the end of the game. Django then, is also about using brute force, with a big gun or a big bang to drive everyone off the train and enable him to scoop up the loot.

In Colt Express, Django is a crackshot and when he shoots another Bandit, he or she is knocked into the next carriage. In Colt Express Bandits – Django, he still has that capability, but here he fires a volley, the bullets hitting the nearest group of Bandits rather than a single Bandit! In addition, at the beginning of the game, each other Bandit receives two Ejection tokens, and at the beginning of each turn, Django places a Dynamite token in the carriage he is currently in if it does not have one. When the Explosion Action card is draw, all of the Bandits caught in the explosions are ejected from the train and must use their next action to reboard the train. Any Bandit ejected from the train in this fashion must give one of their Ejection tokens to Django and these are worth money at the end of the game. Django then, is also about using brute force, with a big gun or a big bang to drive everyone off the train and enable him to scoop up the loot. In Colt Express, Doc is in smartest Bandit and always starts each round with seven Action cards rather than six like everyone else. In Colt Express Bandits – Doc gets to be cleverer too. First the Bandit who shoots or punches Doc earns his respect and his Respect card, allowing that Bandit’s Player to control Doc until another Bandit shoots or punches Doc. Doc also shoots special bullets which deny the shot Bandit particular actions, such as Fire, Floor Change, Punch, or Move, depending on the card. Doc also sets up a Poker Game, which forces every Bandit with loot to participate by contributing one of their already purloined loot, with Doc adding one from his stake. The player controlling Doc gets to redistribute this loot, Doc receiving two, and everyone else one bar a single Bandit who gets nothing. This is a slightly fiddly, slightly more complex expansion, the player controlling Doc getting to feather his Bandit’s own nest whilst ensuring his rival Bandits, including Doc does not receive as much.

In Colt Express, Doc is in smartest Bandit and always starts each round with seven Action cards rather than six like everyone else. In Colt Express Bandits – Doc gets to be cleverer too. First the Bandit who shoots or punches Doc earns his respect and his Respect card, allowing that Bandit’s Player to control Doc until another Bandit shoots or punches Doc. Doc also shoots special bullets which deny the shot Bandit particular actions, such as Fire, Floor Change, Punch, or Move, depending on the card. Doc also sets up a Poker Game, which forces every Bandit with loot to participate by contributing one of their already purloined loot, with Doc adding one from his stake. The player controlling Doc gets to redistribute this loot, Doc receiving two, and everyone else one bar a single Bandit who gets nothing. This is a slightly fiddly, slightly more complex expansion, the player controlling Doc getting to feather his Bandit’s own nest whilst ensuring his rival Bandits, including Doc does not receive as much. In Colt Express, Ghost is the sneakiest of the Bandits and can place his first Action card face down into the common deck rather face up as is standard. In Colt Express Bandits – Ghost, he is after the Special Suitcase which replaces the Strongbox which begins play in the locomotive, guarded by Marshal. Any Moves he makes is always towards the Special Suitcase, but he also has combined action which enable him to do a Floor Change and then Fire, and his Fire and Punch actions affect every Bandit in the same carriage. Ghost is all about obtaining the Special Suitcase and will win the game if he has at game’s end, so when Ghost is in play, the game becomes about denying him the Special Suitcase as much as it is stealing as much loot as possible.

In Colt Express, Ghost is the sneakiest of the Bandits and can place his first Action card face down into the common deck rather face up as is standard. In Colt Express Bandits – Ghost, he is after the Special Suitcase which replaces the Strongbox which begins play in the locomotive, guarded by Marshal. Any Moves he makes is always towards the Special Suitcase, but he also has combined action which enable him to do a Floor Change and then Fire, and his Fire and Punch actions affect every Bandit in the same carriage. Ghost is all about obtaining the Special Suitcase and will win the game if he has at game’s end, so when Ghost is in play, the game becomes about denying him the Special Suitcase as much as it is stealing as much loot as possible. In Colt Express, Tuco can shoot up or down through the roof of the carriage he is, targeting a Bandit who is on the roof if he is in the carriage or a Bandit who is in the carriage if Tuco is on the roof. In Colt Express Bandits – Tuco, he can still do that. When he takes a Move Action, it is always towards the largest group of Bandits and as with other Bandits, his Punch and Shoot attacks affect multiple Bandits in or on the same Carriage. Tuco’s double-barrelled shotgun fires more bullets though and although Tuco cannot win by expending all of his bullets, he gets extra bullets and receives loot for each bullet fired. In addition, Tuco can swap places with the Marshal and if another Bandit forces Tuco to be in the same carriage as the Marshal, the offending Bandit receives a Wanted token. Each Wanted token adds to a Bandit’s final score, including Tuco’s. So Tuco wants to avoid the Marshal if he can because he is wanted and rival Bandits want to get Tuco and the Marshal together.

In Colt Express, Tuco can shoot up or down through the roof of the carriage he is, targeting a Bandit who is on the roof if he is in the carriage or a Bandit who is in the carriage if Tuco is on the roof. In Colt Express Bandits – Tuco, he can still do that. When he takes a Move Action, it is always towards the largest group of Bandits and as with other Bandits, his Punch and Shoot attacks affect multiple Bandits in or on the same Carriage. Tuco’s double-barrelled shotgun fires more bullets though and although Tuco cannot win by expending all of his bullets, he gets extra bullets and receives loot for each bullet fired. In addition, Tuco can swap places with the Marshal and if another Bandit forces Tuco to be in the same carriage as the Marshal, the offending Bandit receives a Wanted token. Each Wanted token adds to a Bandit’s final score, including Tuco’s. So Tuco wants to avoid the Marshal if he can because he is wanted and rival Bandits want to get Tuco and the Marshal together.Set-up is simple enough. The Action deck for each Colt Express: Bandits expansion is placed to the right of the first player. Between the first player’s action and the second player’s action, one card is drawn randomly from the Bandit’s Action deck and added to the common deck which will be resolved at the end of the round. Each of the Bandits in the Colt Express Bandits series can be shot by his or her rival Bandits and when shot three times, he or she loses her next action. Each also has his or her own winning conditions. Belle wins by having the most jewels at the end of the game. In which case all of the actual players and their Bandits lose! Cheyenne wins by being the richest of the Bandits at the end of the game who has not been poisoned. Django wins the game immediately if he gets all of the Ejection Tokens—essentially if every other Bandit is blown or shot from the train twice! He can also win by being the richest Bandit. Doc wins by having the most loot. Ghost wins by having the Special Suitcase at the end of the game or having the most loot. Tuco wins by having the most loot.

What is interesting is that elements of the Colt Express Bandits could be incorporated into the main game. So Belle could use her charm on the Marshal, Cheyenne could use her Poisoned Arrows, Django could seed the train with Dynamite and set off the explosions, Doc could play the Poker game, Ghost by possessing his Special Suitcase, and Tuco by avoiding the Marshal. However, they are not necessarily designed for that and they are not designed as written to be used as more than one entry in the Colt Express: Bandits expansion at a time. This is not to say that an enterprising group could do that, or even an enterprising player, with the latter actually controlling his own Bandit, whilst the game controls the rest. This would make it fairly complex in working out what happens and when, but if the players are methodical about it, then it should not necessarily be an issue.

Physically, each entry in the Colt Express: Bandits series is well done. The cards are the same quality as those found in Colt Express, the tokens are on thick cardboard, and the little rules leaflet—print in French and English is generally easy to read. However, the English translation is not quite as smooth as it could have been and it could have done with another edit.

Each of six entries in the Colt Express: Bandits series is, to varying degrees, interesting and engaging, and brings out more character from each of the Bandits. The owner of the game is free to pick and choose which of them he wants to, but the likelihood is that he will want all of them, to give him and his gaming group the option to play the Bandits that they want and still have the equivalent of six Bandits in the game. However, this does feel like an expensive option, when perhaps all six expansions could have been collected into the one box (that said, all six expansions in the series will fit the box for Colt Express) and then expanded perhaps with advice on using them for solo play—that is, one player Bandit and five game-controlled bandits and how they might interact. Or on adding the abilities given in this series to the standard play of the Bandits with any of the entries in the Colt Express: Bandits series. As it is, a gaming group, and possibly a single player will have to find that out for themselves how the entries in the series for themselves.

Colt Express is still a great game and the Colt Express: Bandits series adds further flavour and character to each of the Bandits in play. Some options are more complex than others, but overall, adding one or two of these to game should keep the game play fun and add a little challenge and chaos at the same time.