Outsiders & Others

The Aftermath: Dallas Oddities & Curiosities Expo 2021 – Introduction

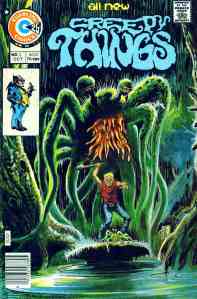

Monstrous Mondays: Monster Collections

So no monster today. I am getting ready for my big April A to Z of Monsters later this week.

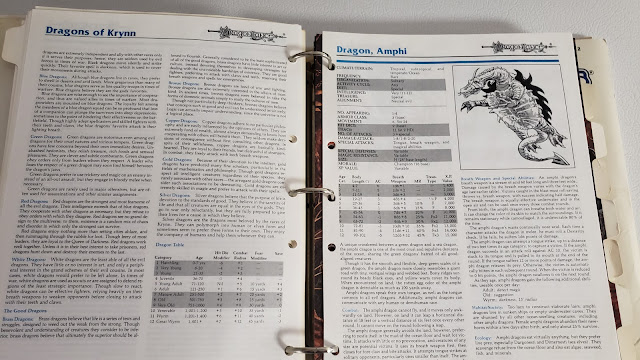

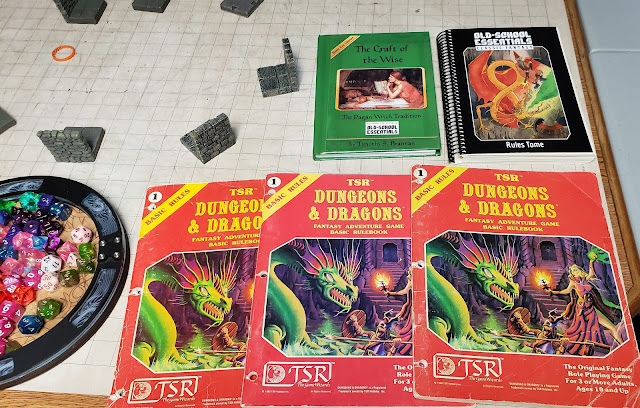

I was on vacation last week and getting these "new" AD&D 2nd Edition setting books made me think a bit about what I might do with them. But since monsters are also on my mind I decided it was high time to pull out my old Monstrous Compendiums for AD&D 2nd Ed, and finally get them organized.

I don't recall exactly when, but I misplaced, lost, or sold my original Monstrous Compendiums. I kinda regret it really, I got them on the days they were released. I loved the idea of them. A monster per page full of information. Even some bits on the ecology of each. I had ideas of cutting out the various "Ecology of" articles from Dragon and putting them in each one for a full encyclopedic entry of every monster.

While the idea sounds great, in practice the Monstrous Compendiums were a bit of a hassle. They were large and unwieldy and yes the pages kept getting torn. The big thing for me was the fact I could note "really" put the monsters in true alphabetical order since they were printed back to back. I know, gamer problems.

So I pulled everything I had, everything I have managed to round up at actions, used book stores and even a few others, and got both folders finally put together.

In addition to the first two sets (all in the first binder) I got the sets for the Forgotten Realms, Dragonlance, the Outer Planes, and my beloved Ravenloft all in the second binder.

I just need to replace my Greyhawk and Mystara ones now.

I know I have some more in boxes somewhere, so I'll get those added as well. Since I am not longer a transient college student with all my D&D books in a couple of milk crates they can live nicely on my bookshelves. Here they would likely to get more use and less wear and tear.

They live nicely next to my Castles & Crusades Monsters & Treasure Compendium, Next to them is something I am working on printing out; the contents of the Swords & Wizardry versions of Monstrosities and Tome of Horrors Complete. It is going to be about 1200 or more pages of monsters. This time I am not printing them back to back, but a true one page per monster. Yeah, that means a lot more paper, but also a lot more ease of use and lots of room for me to include notes. IT will also be hard on my printer.

While there is a core of about 400-500 monsters that are shared across all editions of D&D and clones, there are something like 6,000+ monsters that have been stated up in official products. Once upon a time, I would have wanted all of them. Today I am a bit more reasonable.

OR at least that is what I tell myself.

Miskatonic Monday #62: The Highway of Blood

The Highway of Blood: A Call of Cthulhu Scenario for the 1970s is a one-shot scenario for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, published on the Miskatonic Repository. It stands out as being different for four reasons. First, it is set during the nineteen seventies. Second, it is inspired by the low-budget horror, splatter, and exploitation films of the period, shown in a ‘grindhouse’ or ‘action house’ cinema, such as Duel, I Spit on Your Grave, Last House on the Left, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes, and the more recent Death Proof. Third, in doing so, the scenario involves a number of elements which the players may find disturbing. In fact, more disturbing than is the norm for a Call of Cthulhu scenario. These include drug use, sadistic violence, implied rape (against NPCs), torture, cannibalism, body horror, and violence against children. Consequently, the scenario comes with a warning and advice on how to handle such topics, including making clear to the players the nature of the content of the scenario and discussing any boundaries they may have—essentially a ‘Session Zero’, if necessary fading to black and drawing a veil in what might otherwise be a personally harrowing scene, and ultimately respecting a player’s limits. Even if that means ending the current session. So to be clear, The Highway of Blood is not a scenario for the timid or the easily offended, its content is of a grittily adult nature and so requires mature players, but it goes out of its way to be upfront about this and gives advice on how to handle it.

The Highway of Blood: A Call of Cthulhu Scenario for the 1970s is a one-shot scenario for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, published on the Miskatonic Repository. It stands out as being different for four reasons. First, it is set during the nineteen seventies. Second, it is inspired by the low-budget horror, splatter, and exploitation films of the period, shown in a ‘grindhouse’ or ‘action house’ cinema, such as Duel, I Spit on Your Grave, Last House on the Left, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes, and the more recent Death Proof. Third, in doing so, the scenario involves a number of elements which the players may find disturbing. In fact, more disturbing than is the norm for a Call of Cthulhu scenario. These include drug use, sadistic violence, implied rape (against NPCs), torture, cannibalism, body horror, and violence against children. Consequently, the scenario comes with a warning and advice on how to handle such topics, including making clear to the players the nature of the content of the scenario and discussing any boundaries they may have—essentially a ‘Session Zero’, if necessary fading to black and drawing a veil in what might otherwise be a personally harrowing scene, and ultimately respecting a player’s limits. Even if that means ending the current session. So to be clear, The Highway of Blood is not a scenario for the timid or the easily offended, its content is of a grittily adult nature and so requires mature players, but it goes out of its way to be upfront about this and gives advice on how to handle it.The Highway of Blood takes place in 1975, along The Devil’s Backbone, a scenic drive along a limestone ridge in the Texas Hill Country. It is purportedly one of the most haunted spots in the Lone Star State. The Player Characters, who might be friends on a week-long road trip through West Texas, or FBI agents from the Dallas office who are investigating a series of disappearances in the area, begin play on the road, getting low on fuel and in one of the worst heat waves the region has ever seen, also in need of a cold drink. When they see a sign up ahead promising ‘Gas & Food’, the Player Characters make the necessary right turn onto the unpaved road and find themselves in the crumbling, mouldering former uranium-mining town of Abattoir, West Texas (population of 850, but probably much less…). Unfortunately, getting into Abattoir, West Texas, is the easy part. Getting out is going to be challenging, not to say nigh on impossible, and is likely to be tortuous. In some cases, literally…

The fourth reason why The Highway of Blood is different, is the format. It is not a traditional Call of Cthulhu scenario in that it is a strong plot driven by an investigation, with layers of the mystery being peeled back layer by layer as the Investigators make their enquiries. Instead, it is written as a sandbox-style scenario in which the Player Characters are free to go anywhere they like, though they are likely to be harried and hindered by the evil inhabitants of Abattoir and its environs everywhere they go. To that end, The Highway of Blood describes the town and surrounding locations in some depth, including the inhabitants and the items which might be found there—sometimes on lengthy random tables. The locations include the gas station, the diner, the church, and the few surviving shops in the town itself. Then beyond the confines of the town, the roads which crisscross the area, the camp and mine shafts for the long since shutdown uranium mine, a horridly bloody compound, and below the mine, a series of strange caves and tunnels. All described in some detail and all sites which the Investigators can visit as part of their sojourn in and around Abattoir.

The plot—as much as there is a plot in The Highway of Blood—is primarily driven by two urges. One is the urge by the debased and often inbred townsfolk to harass and harry, even play, with the Player Characters, and keep them in Abattoir, whilst the other is Player Characters’ urge to escape Abattoir. The highlight of this—if there is one—is the set piece car chase over the roads surrounding the town. This is ‘The Hunt’, and it is very obviously inspired by the car chases seen in the Grindhouse genre. Beyond this hunt, the motivations and plans of the scenario’s antagonists are discussed in some detail, as are possible outcomes or endgames…

The Highway of Blood is supported by a number of appendices. The first provides an overview of ‘The Hunt’, including optional car rules to supplement the chase rules in Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition; and rules for non-lethal attacks (since the antagonists do not want to actually kill the Player Characters) and driving stunts. The second provides environment rules for the desert and various hazards; the third the full statistics and write-ups for the various NPCs; the third the monsters; and the fifth, descriptions of new spells and items, plus new rules for radioactive dust and water. The sixth gives the scenario’s various handouts, including numerous maps and floor plans, plus portraits for all of the NPCs and details of the vehicles the Player Characters and their enemies drive during the scenario. The seventh appendix provides two sets of pre-generated Player Characters. One is a quartet of twenty-somethings on a week-long road trip, whilst the other is a pair of FBI agents looking into a rash of disappearances in the area. The eighth and last appendix provides a thumbnail guide to playing in the seventies—news and pop culture in 1975, slang, and recommended films. All useful for anyone who was not born then or was too young to remember the period, or was alive back and then, and has forgotten what it was like.

So what then is The Highway of Blood actually about? It can be best described as the desert version of H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth’. The town of Abattoir is dominated by a cult dedicated to an ancient god whose members seek victims for conception, consumption, and consecration. This is no Escape from Innsmouth though, the emphasis being on the ‘no escape’, again in keeping with the Grindhouse genre. There is a touch of Mad Max in the scenario’s set piece car chase and of Deliverance in the encounters between the Player Characters and the NPCs. Instead of hillbillies of Deliverance or the bachtrachian inbreds of Innsmouth, what The Highway of Blood has is ‘Dustbillies’. There are potential allies to be found in Abattoir, but to a man—and there are no active female NPCs in the scenario—all have either been cowed by the cult or actively choose to ignore it. This adds to the challenge of what is already a challenging scenario.

Physically, The Highway of Blood is decently appointed. It is presented in full colour with a mixture of period colour photographs and photographs, as well as black and white photographs from the nineteen thirties onwards. The floorplans are clean and easy to read, as are the maps in general. Some thought has been given to highlighting the key points in the scenario and in particular, key trigger warnings for the horrific situations in the scenario. Throughout, there is staging advice and directions for the Keeper, most notably appropriate music to play at certain points, as well as the voiceover from a state radio disc jockey. In addition to it needing an edit in places, if there is an issue with The Highway of Blood, it is that the Keeper could have been given a bigger, better map of the region and it be placed more upfront for her reference.

As a scenario, The Highway of Blood is difficult to quantify. This is because as a sandbox scenario, a form more readily seen in the Old School Renaissance rather than in Call of Cthulhu, it very much being very player driven with relatively little in the way of the plot or NPC to pull them along. In fact, the plot more pushes the Player Characters along as the inhabitants of Abattoir harass and harry them in and around, but not of, the town. In addition, the format means that unlike a traditional Call of Cthulhu scenario, there is not the readymade trail of breadcrumbs or clues for the Player Characters to follow, so that because The Highway of Blood is a sandbox, the Player Characters can more easily avoid any and all clues, run into a major threat and get captured and/or butchered in the first hour or so, or simply wander around never finding anything, just desperate to escape… So a play through of The Highway of Blood could last an hour or hours over multiple sessions. And even if the Player Characters do manage to escape, they may not necessarily succeed or find a solution which deals with the threat they face in Abattoir. That said, the players and their characters have to be both lucky and resourceful if they are to fully deal with this threat, the likelihood being that they will ultimately fail, get captured, and the scenario fades to black as the Player Characters scream in terror. Such an ending though, would be in keeping with the Grindhouse genre that The Highway of Blood is inspired by.

Ultimately, the nature of The Highway of Blood is what will make a gaming group decide whether to play it or not. The triggering issues it contains means that it is definitely one to avoid for some players, but those issues are part of the genre and the authors should be praised for addressing how to handle them as well as they do. The scenario is also less useful for a campaign, though there is advice to that end, being better suited to one-shot play. For a gaming group looking to play a grim, gritty, and gruesome Grindhouse scenario, The Highway of Blood: A Call of Cthulhu Scenario for the 1970s is the perfect choice.

A Mythic Neo-Noir Starter

City of Mist is a roleplaying game of neo-noir investigation and superhero-powered action. The intersection between the film noir and superhero genres has invariably derived from the Pulp fiction of the thirties and forties, with such characters as The Shadow or Batman, with generally low-key and low-powered heroes and villains in comparison to what would follow with the Four Colour subgenre. City of Mist does something different. It brings in the powers and personalities of legends and gods of different Mythos—King Arthur, Red Riding Hood, Hercules, Athena, and Bast—and then obscures them. These powers and personalities manifest through Rifts, inhabitants of The City, a fog-shrouded, corrupt, and crime-ridden metropolis which could be Los Angeles of the thirties, New York of the fifties, or London of the sixties. It is simply known as The City. As Rifts, the Player Characters investigate Cases, and if necessary, fight crime, some of it committed by other Rifts, some not. Yet as powerful as each Rift is, the ordinary citizens of The City, the Sleepers, cannot see them for what they are and never see them manifest their powers. The Mist, a strange mystical veil renders each manifestation of a power or legend ordinary. Wallcrawling? Parkour. Lightning bolt? Broken electrical substation. Each Mythoi—god or legend or even abstract concept wants to manifest itself in The City, but the Mist works to prevent this, for the result might be chaos which could rip The City apart, so instead it allows them to manifest through the Rifts. Equally, as there is a tension between the Mythoi and the Mist, there is tension between the Mythos, both the legend which wants to become more and a mystery as to why it manifested, and the Logos, the ordinary self, safe and mundane in each Rift.

City of Mist is a roleplaying game of neo-noir investigation and superhero-powered action. The intersection between the film noir and superhero genres has invariably derived from the Pulp fiction of the thirties and forties, with such characters as The Shadow or Batman, with generally low-key and low-powered heroes and villains in comparison to what would follow with the Four Colour subgenre. City of Mist does something different. It brings in the powers and personalities of legends and gods of different Mythos—King Arthur, Red Riding Hood, Hercules, Athena, and Bast—and then obscures them. These powers and personalities manifest through Rifts, inhabitants of The City, a fog-shrouded, corrupt, and crime-ridden metropolis which could be Los Angeles of the thirties, New York of the fifties, or London of the sixties. It is simply known as The City. As Rifts, the Player Characters investigate Cases, and if necessary, fight crime, some of it committed by other Rifts, some not. Yet as powerful as each Rift is, the ordinary citizens of The City, the Sleepers, cannot see them for what they are and never see them manifest their powers. The Mist, a strange mystical veil renders each manifestation of a power or legend ordinary. Wallcrawling? Parkour. Lightning bolt? Broken electrical substation. Each Mythoi—god or legend or even abstract concept wants to manifest itself in The City, but the Mist works to prevent this, for the result might be chaos which could rip The City apart, so instead it allows them to manifest through the Rifts. Equally, as there is a tension between the Mythoi and the Mist, there is tension between the Mythos, both the legend which wants to become more and a mystery as to why it manifested, and the Logos, the ordinary self, safe and mundane in each Rift.The City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is designed as an introduction to the setting. Published by Son of Oak Game Studio LLC, it provides everything necessary to play through at least one Case. Designed to be played by five players and a Master of Ceremonies—as the Game Master is known—the starter set comes richly appointed. There are two books labelled ‘The Players’ and ‘The Master of Ceremonies’; five pre-generated character folios, one each for Baku, Detective Enkidu, Job, Lily Chow, Iron Hans, and Tlaloc; a deck of twenty Tracking cards and a Crew Card; two twenty-two by seventeen-inch poster maps; forty-one illustrated character tokens; and two City of Mist dice—one purple Mythos die and one ivory Logos die. There is a lot on the box, all of it presented in full colour and illustrated throughout with artwork which invokes the two inspirations for City of Mist.

The starting point for the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are five pre-generated Player Characters or Rifts. The quintet consists of Baku, Detective Enkidu, Job, Lily Chow and Iron Hans, and Tlaloc. Baku is a monster hunter, mythological Japanese chimera who hunts ghosts and devours nightmares; Detective Enkidu is an experienced police detective who hides a creature of the wild from Sumerian myth inside her which drives her to break the rules; Job is an unkillable priest whose family was killed by The City’s criminal underworld; Lily Chow is a runaway teen able to unleash Iron Hans, a magician-giant who is her companion, protector, and big brother; and Taloc is a small time crook with a gift of the gab and the power of the Aztec god of rain and water, thunder and lighting. Each of the five character folios is done on heavy, glossy card in A3-size. This does mean that there is quite a lot of information on each folio and that each folio takes up quite a bit of space on the table.

The starting point for the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are five pre-generated Player Characters or Rifts. The quintet consists of Baku, Detective Enkidu, Job, Lily Chow and Iron Hans, and Tlaloc. Baku is a monster hunter, mythological Japanese chimera who hunts ghosts and devours nightmares; Detective Enkidu is an experienced police detective who hides a creature of the wild from Sumerian myth inside her which drives her to break the rules; Job is an unkillable priest whose family was killed by The City’s criminal underworld; Lily Chow is a runaway teen able to unleash Iron Hans, a magician-giant who is her companion, protector, and big brother; and Taloc is a small time crook with a gift of the gab and the power of the Aztec god of rain and water, thunder and lighting. Each of the five character folios is done on heavy, glossy card in A3-size. This does mean that there is quite a lot of information on each folio and that each folio takes up quite a bit of space on the table.Unlike a traditional roleplaying game, a Rift is not described in terms of skills or attributes, but rather what he can do. Each of the five has the same set of Core Moves, or actions that they can attempt. What marks a Rifts out as special is the fact that he has four Themes, represented by four cards on the folio. They are divided between Mythos and Logos Themes, the legendary and the ordinary aspects of a Rift. Some Rifts have Mythos Themes than Logos Themes, and vice versa, and it is possible to lose Themes, so that a Mythos Theme might Fade and be replaced by a Logos Theme, whilst a Logos Theme might Crack and be replaced by a Mythos Theme. There are consequences to having Themes all of one type. For example, a Rift who replaces all of his Logos Themes with Mythos Themes, becomes an avatar of his Mythos, whilst losing his last Mythos Theme means he becomes a Sleeper and denies the existence of the Mythos. Whilst each Mythos Theme has a Mystery that the Rift wants to explore, and each Logos Theme has an Identity which represents a defining conviction, belief, or emotion, all Themes have Power Tags which can be invoked to help achieve a Rift’s intended goal, plus a Weakness.

For example, Tlaloc has the Mythos Theme ‘God of Rain and Lightning’. This has the Mystery, “Who Threatens to Blot Out the Fifth Sun?”, the Power Tags, ‘Call Upon the Storm’, ‘Thunderbolt Manipulation’, and ‘Electrifying Gaze’, plus the Weakness, ‘Indoor Spaces’. He also has the ‘A Dimond in the Rough’ Logos Theme, which as the Identity, “This Will Be The Last Time, I Swear!”, the Power Tags, ‘Good, deep down inside’, ‘Relentless Schmoozer’, and ‘Sticky Fingers’, as well as the Weakness, ‘Pangs of Remorse’.

Learning the game begins with ‘The Players’ booklet. It runs to forty-four pages and introduces the concepts behind roleplaying and City of Mist, explains the character folios and how the roleplaying game is played—the ‘Moves’ or actions a Rift can take and their potential outcome, describes the various districts of The City, and provides a lengthy, eight page example of play. The latter includes two of the pre-generated Rifts in the starter set and showcases the various types of Moves that the Rifts can perform as part of an investigation and then combat scene. In general, the Moves are well explained, but do come with fine print and do require a little bit of study. The example of play though, is more than helpful in showing the prospective player and Master of Ceremonies how the game works.

Whilst the Master of Ceremonies has to read the ‘The Players’ book to understand the basics of City of Mist, the ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book is all hers. This explains the role of the Master of Ceremonies, the Moves or actions she can take—and when, explains how to present challenges and dangers to the Rifts, and so on. A Danger encapsulates a threat to the Rifts, whether that is an NPC, a location, or a situation, which might be a crime lord’s chief enforcer, a car chase through the streets of The City, or a building on fire. The bulk of the ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book is given over to ‘Shark Tank’, the first case for ‘All-Seeing Eye Investigations’, the crew which the Rifts in the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are members of. ‘All-Seeing Eye Investigations’ has its own ‘Crew Theme card, complete with its own Mystery and Power Tags which the Rifts can invoke as part of their investigation.

Mechanically, City of Mist and thus the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’, which means that it uses the rules first seen in Apocalypse World in 2010. These rules are player-facing in that the Master of Ceremonies does not make dice rolls, but rather that the player do. So from the Core Moves below, a player would roll ‘Convince’ to persuade an NPC, but ‘Face Danger’ to avoid being influenced. The rules in City of Mist have eight Core Moves—‘Change The Game’ (give an advantage or remove a disadvantage), , ‘Face Danger’ (avoid harm or resist a malign influence), ‘Go Toe to Toe’ with someone, ‘Hit With All You’ve Got’ (harm someone in the worst way you can), ‘Investigate’, ‘Sneak Around’, and ‘Take the Risk’ (perform a feat of daring). When a Rift undertakes an action, his player states the Move he is using, applies any bonuses from Tags—short descriptors for a quality, resource, advantage, disadvantage, or object in the game—and applies the resulting Power value for the sum of positive and negative tags and statuses affecting an action, and rolls two six-sided (or the included City of Mist dice) dice. A player can use all manner of Tag Combos to build up the Power value, as long as the Master of Ceremonies agrees. Several Tag Combos tailored to each pre-generated Rift are listed in their respective folios.

A result of a six or less is a Miss, a result of between seven and nine is a Hit, but with complications, whilst a result of ten or more is a Hit with a great success. Each Move works slightly differently and will give different results depending upon the roll. For example, the ‘Investigate’ Move gets a Rift answers to questions. If a Hit—seven or more—is rolled, the player can ask the Master of Ceremonies a number of questions and so gain a number of Clues equal to the Power value applied to the roll. If a Hit with complications—seven or more, but less than ten—is rolled, the Master of Ceremonies can expose the Rift to danger, give fuzzy, incomplete, or partly-true partly-false answers, or have the NPC ask the Rift a question, which he must answer. The aim in many Moves is to inflict a Status such as ‘Prone-2’ or ‘Befuddled-1’ or ‘Knife Wound-3’, which will give a Rift an advantage when rolling against that NPC who has suffered such a Status and a disadvantage when suffered by the Rift. A status like this is recorded on a Status card and kept in play until it is got rid of.

In addition, the Rifts can enter a Downtime sequence between the investigation or action, and undertake actions such as ‘Give Attention to a Logos’, ‘Work the Case’, ‘Explore Your Mythos’, ‘Prepare for your next Activity’, and ‘Recover for your next Activity’. This is handled as a montage scene and the effects of each action are automatic, whilst ‘Burning for a Hit’ grants an automatic success without complications, but also makes the Tag unusable until a Downtime sequence has been completed. Lastly, there is ‘Stop.Holding.Back.’, a special Move which enables a Rift to push his powers beyond their limit, though at the cost of a sacrifice to one of the Themes in a Rift’s folio.

The Master of Ceremonies has her own Moves, divided between Soft Moves and Hard Moves. A Soft Move is an imminent threat or challenge to the Rifts and their investigation, and really only consists of the Master of Ceremonies complicating things for the Rifts as a means to spur them into action. A Hard Move is a major complication or a significant setback to the Rifts and their investigation, and includes more options for the Master of Ceremonies. ‘Give a Status’ inflicts a Status on a Rift, but this can be resisted by a ‘Face Danger’ Move. Other Hard Moves, such as ‘Burn a Tag’, ‘Complicate Things, Big-time’, and others cannot be resisted and are more narrative effects and consequences than Moves as such. Essentially, they can come into play when a Rift fails to take an action or fails—rolls six or less—when undertaking an action. The Master of Ceremonies also has Intrusions, which really codify her using her judgement when adjudicating the rules.

The Case in the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set, ‘Shark Tank’ is organised in a couple of ways. First, it is a pyramid diagram of scenes, arranged by depth into a series of layers, which after the briefing, the Rifts can visit and investigate. Second, it is as a series of programmed steps which take the Master of Ceremonies and her players through the process of learning to play both City of Mist and the scenario. For example, when the Rifts encounter a group of enforcers shaking down a shop owner, ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ book says, “If this is the crew’s first fight, stop the story and move over to the players’ booklet, starting at Exhibit #8: Playing Through a Conflict on page 21 (see also MC Skill: Running a Fight Scene on the next page).” At which point, the players and Master of Ceremonies can set up and run the fight scene. However, this does not mean that the Master of Ceremonies can necessarily run ‘Shark Tank’ without any preparation, but it does mean that once prepared, she really has all of the references, pointers, and advice at her fingertips, including advice specific to each of the five Rifts which come pre-generated with the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set. The scenario itself has the Rifts interviewing the owners of several businesses on Miller’s Square where All-Seeing Eye Investigations has its shabby office, potentially exposing police corruption, confronting villains who bring a whole new meaning to the term ‘loan shark’, and having a showdown at the chief villain’s lair. Beyond the confines of ‘Shark Tank’, there are extra scenarios available which can be played using the content from the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set.

Also included in the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set are two twenty-two by seventeen-inch poster maps and forty-one illustrated character tokens. The maps depict various locations which appear in the scenario, ‘Shark Tank’, and tokens cover all five Rifts and the various NPCs in the scenario. The single purple Mythos die and single ivory Logos die are decent twelve-sided dice marked with one through five twice, and then the domino mask symbol on the six face for the Logos die, and power icon on the six face for the Mystery die. Each icon also appears on the Themes in each folio.

Physically, the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is very nicely put together. The poster maps are on sturdy paper, the counters thick cardboard, the folios on glossy card stock, and both of ‘The Players’ and ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ booklets done on glossy paper stock. Inside, both booklets are superbly illustrated in a slightly cartoonish, but suitably film noir style, and their layout is excellent. Not only designed to look like a set of case files for a crime, but also designed to be accessible with effective use of devices to highlight text and boxed text for useful information. If there is a physical downside to the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set, it is the box it comes in. It is not particularly sturdy and unlikely to do a good job of protecting its otherwise excellent contents.

The City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is at first confusing. The box contains a lot of components and it is a little difficult to quite know where to start. However, once you dig into the rules in the ‘The Players’ booklet it begins to make a little sense, but really where it comes together is in ‘The Master of Ceremonies’ booklet, especially in the scenario, ‘Shark Tank’, which gives context for the rules and whether through nudges to the Master of Ceremonies to use particular rules or direct referral back to the rules in ‘The Players’ booklet. Once grasped, what the City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set reveals is a flexible ruleset which drives and pushes the narrative. The setting itself, combines urban fantasy with super heroics, but that combination avoids much of the trappings of the superhero genre. It shrouds them in the fog of the film noir genre just as The Mist masks The City from them. The City of Mist: All-Seeing Eye Investigations Starter Set is an excellent introduction to The City and the ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ mechanics of City of Mist.

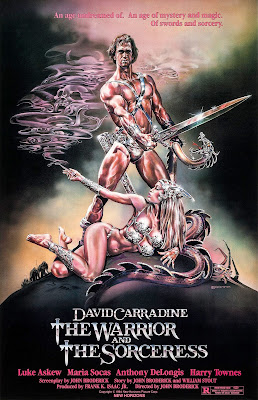

Sword & Sorcery & Cinema: The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982)

Another fairly notorious one. I can recall gamers in my Jr. High talking about how to stat up the sword from this. The start of this one is fun, love the wall of screaming faces.

Another fairly notorious one. I can recall gamers in my Jr. High talking about how to stat up the sword from this. The start of this one is fun, love the wall of screaming faces.Among others, this features Richard Lynch as Titus Cromwell the evil king (naturally) and Richard Moll as Xusia the evil sorcerer. On the side of good, we get Lee Horsley as Prince Talon just before he became Matt Houston and Kathleen Beller, the future Mrs. Thomas Dolby*, as Princess Alana.

I only mention her as the "future Mrs. Thomas Dolby" because that was my first real knowledge of her, on the cover of his "Aliens Ate My Buick" album.

So let's get to this!

The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982)

So Richard Lynch summons Richard Moll to help him fight King Richard (Christopher Cary). Of course, no sooner had he got help from the sorcerer Xusia, Cromwell kills him.

We also get our first look at the ridiculous three-bladed sword. It can cut, slice, and fire blades!

Eleven years later Talon (now looking like Lee Horsley) comes back home to avenge his father and mother.

There is a bit with Manimal I mean Prince Mikah played by Simon MacCorkindale and George Maharis, a long way from Route 66, as Machelli. We also get another showing of S&S&C MVP Anthony De Longis appears as Rodrigo.

I have never watched it all the way through. I honestly could never get past the sword firing blades. Watching it now I remember why.

The prince is rescued but they fight their way out. There seems to be a bit of Raiders of the Lost Ark envy here; Talon's escape could be taking place in Cario, Egypt.

Talon fights Cromwell only to have Xusia come back. I have to admit Xusia's return is kind of fun, it would have been better if they hadn't telegraphed it. Xusia and Talon fight over who gets to kill Cromwell. Talon kills the sorcerer and then he and Cromwell fight.

Not a great movie but a cult film all the same. I know a lot of people love it, but I could not get into it in the 80s and didn't do much better now.

Gaming Content

Seems fitting seeing how they call out D&D on the poster and there is not a dragon to be found in this.

The Triple-Sword. This sword is +3 to hit and damage. On striking it does 3d6+3 points of damage.

The sword can launch one of two of its outside blades doing 1d6+3 damage. Its range is 30/60/120 feet. Reattaching a blade requires one round in which the wielder cannot attack.

Tomorrow's Future Today

The Future We Saw is a near-future, post-scarcity, post-labour roleplaying game of A.I. and precognitive manipulation of politics, power, privacy, and information in a world of radical political, corporate, and social factions. This is a future in which corporations and other organisations not only have their own public relations teams to make themselves look good, but teams of undercover fixers whose task is to ensure that their employer looks good and their employer’s rival looks bad, that they have the inside information on their rivals, whilst denying inside information to their rivals. Working in small team ‘Special Forces’ style operations, these fixers will conduct acts of blackmail and kompromat, assassination and intimidation, infiltration and hacking, extraction and kidnapping, sabotage and discovery, and more. Each team will comprise combat and protection Veterans, technical Specialists, Psy-Ops who provide medical and psychological support, and Seers, precogs capable of seeing Glimpses and Gazes into the possible future, and so potentially avoid them—though not without suffering high degrees of stress such that it is not uncommon for Seers to burn out.

The Future We Saw is a near-future, post-scarcity, post-labour roleplaying game of A.I. and precognitive manipulation of politics, power, privacy, and information in a world of radical political, corporate, and social factions. This is a future in which corporations and other organisations not only have their own public relations teams to make themselves look good, but teams of undercover fixers whose task is to ensure that their employer looks good and their employer’s rival looks bad, that they have the inside information on their rivals, whilst denying inside information to their rivals. Working in small team ‘Special Forces’ style operations, these fixers will conduct acts of blackmail and kompromat, assassination and intimidation, infiltration and hacking, extraction and kidnapping, sabotage and discovery, and more. Each team will comprise combat and protection Veterans, technical Specialists, Psy-Ops who provide medical and psychological support, and Seers, precogs capable of seeing Glimpses and Gazes into the possible future, and so potentially avoid them—though not without suffering high degrees of stress such that it is not uncommon for Seers to burn out.The Future We Saw is published by Lost Pages, best known for its Old School Renaissance titles such as Genial Jack Vol. I and the Burgs & Bailiffs series. It employs the mechanics from Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition to provide four Classes—each of which goes up to Fifth Level, near-future skill and tool Proficiencies, and the spell-like Glimpses and Gazes of the Seer. In addition, it covers the types of factions found tomorrow—if not today—and the means to set up a Scheme, or campaign, in which factions will send teams on Missions against their rivals to gain or prevent leverage, perhaps discovering other information, which will lead to further Missions, and so on. Lastly it includes a campaign setting, set-up, and scenario in tomorrow’s Dublin written by the author of Macchiato Monsters: Rules for Adventures In a Dungeonverse You Build Together.

The Future We Saw is not a Cyberpunk roleplaying game. Not only does it lack the chrome and neon aesthetics, it is not about technology and our inability to integrate with it, and it is not about the masses versus megacorporations or working to bring them down. The various factions in The Future We Saw are in power, so it is about sabotaging them, manipulating them, and controlling them rather than destroying them, and all for the benefit of another faction rather than society. The Future We Saw is about the manipulation of a future that has already been lost to the control of corporations and other factions whose promises have failed to deliver as discourse polarised and technology either drove out the need for labour or began to direct it. What technology there is has been subsumed into society, whether that is robot delivery drones or mobile devices or A.I.-driven vehicles—essentially all recognisable from today, and in terms of game play there are no hacking rules. Instead hacking is handled offscreen by an NPC, if at all. However, labour is at least useful for providing a human face, or stepping in when A.I. cannot cope or needs to be repaired, but in the main, robots do much of the work. However, constant working with A.I. has caused mental illness in many, even triggering a precognitive ability in some. Typically, this comes in the form of a hallucination which suggests the best possible outcome, but not whether the action will succeed, such that the powers of a Seer are powerful, but not absolute. However, such predictions, known as Sights, can fail due to errors in belief, the blurring of details, focus upon incidental details, and personal bias as well as the Seer’s mental health.

An Agent in The Future We Saw has the six attribute scores of Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition—Strength, Constitution, Dexterity, Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma. Each of the four Agent Classes grants various Proficiencies—Saving Throws, Armour, Weapons, and Skills, as well as a series of features. For example, the Specialist starts with Expertise—double Proficiency with two skills and Specialist Training. This can be Thug, essentially the equivalent of the Rogue’s Backstab; Contacts, which grants Advantage on Charisma checks when dealing with criminal contacts; or Meaningful Practice, which grants a bonus action with one particular tool the Agent has Proficiency with. Two means of Agent creation are given. One is an array for the ‘Typical Professional’, whilst the standard three six-sided dice are rolled for those ‘From Other Walks of Life’. An Agent then receives some bonuses to these and then selects a Class. An Agent does not begin with equipment as this is provided by his employer on a Mission by Mission basis.

Marilyn Hilliard was an actuary working for Solid Life Health Insurance supporting an expert A.I. when she began to see the times of deaths of her customers. This drove her into having a mental health episode and eventually hospital. Her policy and employment was subsequently purchased from Solid Life Health Insurance and she found herself working for an entirely different employer.

Marilyn Hilliard

First Level Seer

Strength 12 (+1)

Constitution 06 (-2)

Dexterity 13 (+1)

Intelligence 14 (+2)

Wisdom 18 (+4)

Charisma 16 (+3)

Hit Points 7

Proficiencies: Light Armour, Simple Weapons

Saving Throws: Intelligence, Wisdom

Skills: Insight, Investigation, Persuasion

Features

Stress Prevision (People)

Future Sight: Emotional Button Mashing, Evil Eye (Glimpses); Alpha-Beta Approach Pruning (Gazes)

A Seer’s capacity to see into the future is divided into ‘Glimpses’ and ‘Gazes’. ‘Glimpses’ grant visions of the future about the Seer’s immediate environment—to see how a combat plays out to pre-empt an action, to determine how a conversation might play out, or to predict the worst possible outcome from a situation. In general, this is to gain a bonus action, a reaction, and so on. ‘Gazes’ take longer, often days at a time, and grant long range predictions, perhaps about the plans of a rival faction or the best possible course of action. Although The Future We Saw does not have hacking rules or mechanics, but the difference between ‘Glimpses’ and ‘Gazes’ maps onto the shift on how hacking is handled in cyberpunk and similar roleplaying games. Originally, hacking was always handled by a Player Character working from a base or home whilst the rest of the team goes on the Mission, essentially ‘Gazes’, but in more recent iterations, hacking needs to be done on scene, that is, the hacker has to go on the Mission. Which is this case, the equivalent of the ‘Glimpses’, visions of the future which happen on site, during the Mission. Predicting the future does not come without its cost. Invoking ‘Glimpses’ and ‘Gazes’ inflicts stress and suffering stress can led to burnout and exhaustion, which can greatly impede an Agent’s capacity to operate. Combat is also dangerous in The Future We Saw as it is possible to suffer grisly wounds.

Ideally, The Future We Saw should be played with four players and thus one of each of the four Agent types in the roleplaying game, though with more players, the doubled up Agents should opt for different specialities to enable each Agent to shine in different ways during play. Doubling up with Seer Agents may set up an interesting dynamic of differing views of the immediate future, but will also complicate the efforts of the Game Master to what that ‘best’ future might be in any given situation. Even with just the one Seer in a team, determining the ‘best’ future might be in any given situation is still one of the more challenging tasks in the roleplaying game for the Game Master.

In terms of setting, The Future We Saw does three things. First it presents and discusses five Factions—Hegemon, Innovator, Movement, Rentier, and Zaibatzu—and what their objectives are, why they are hated and why they are useful, and the three perks they can grant once per Mission. For example, an Innovator represents the Power of Progress, which could be cutting edge technology, pervasive data hoarders and manipulators, and the like, such as gig economy delivery and taxi services, and political consulting firms specialising in data analysis and manipulation. It is hated because it pursues improvements without any qualms about collateral or financial damage, but useful because it is building the future. Their perks include ‘Benefit: SIGINT’—harvesting data means great briefing material, Support: Cutting Edge—new technology; and Ultimate: Hack from the Stash—the possibility that the data breaches have already made in the target of the Mission, but not yet revealed. A diagram shows the relationships between the five types of Factions, so that the Game Master can see the alliances and enmities at a glance.

Second, it examines the types of Missions and Schemes that the Agents can be sent on. Whether an Extraction, Cover-Up, or Kompromat, Missions are played out in seven phases—Briefing, Procurement (assign equipment), Deployment, Execution, Extraction, Debriefing, and Consequences. What is interesting here is that in terms of game play, failure is as interesting as success, since the target Faction (or other Faction) might be running its own team of Agents and failure means approaching the problem again, but from a different angle, even a different type of Mission. Further, throughout the Game Master has her own character to roleplay in addition to the various NPCs in situ, and that is Control, a voice in the Agents’ ears, offering advice, help, and warnings, a la Control of John le Carre’s espionage fiction.

Schemes are the overall objectives of the Faction the Agents are working for, the equivalent of a campaign in other roleplaying games, but relatively short and meant to be flexible and be developed as the Agents play through Missions, make discoveries and the target Factions acts in response. These are mapped out on a ‘FTM’ or ‘Faction Tension Map’, which sets out the specific relationships between the Factions and other organisations or persons involved in the Scheme, willing or not. The relative brevity is supported by the number of Missions the Agents go on to acquire Levels—two Missions to get to Second Level, then three to get to Third Level, and so on, for a maximum of fourteen Missions to get to Fifth Level, the maximum available in The Future We Saw.

Third, The Future We Saw presents a Scheme setting, ‘Dublin 2020’. It details a city divided by wealth and a security Fence, dominated by corporate interests, alco-tourism, and tax breaks. It is supported by complete scenario, ‘L❤VE’s Data’s Lost’, in which the Agents are working for L❤VE, an Innovator and start-up company desperately on the make whose data, much of it private and harvested from its app, has been hacked into on the servers at a nearby server farm. The Faction responsible, ZPLNTR, a radical hacker group, is holding the data hostage and the Agents’ task is to prevent further leaks and get control of the data back. Mix in rival Factions, rival events, and more, and this is a decent starting Scheme which feels just a little too real.

Currently, The Future We Saw is only available in an ‘Ashcan’ or ‘Zero Edition’. This does not mean that it is roughly presented. The layout is clean and tidy, and there is a lot of white space. This is by design, and whilst some may complain, it does give the content room to breath and it makes it easy to read. The artwork is decent and though it needs a slight edit in places, the book is well written.

The Future We Saw is a heist roleplaying game, a roleplaying of small teams of experts conducting missions in small amounts of time. It is like the television series Leverage or Hustle, but with a twist. It is like those television series, but backwards—or rather forwards. In Leverage, the team achieves its aims, playing out a con on its mark, but how the mark is played, how each switch or misdirection is made, is revealed in flashbacks, showcasing the skills and abilities of the team’s members. In The Future We Saw, there are no flashbacks, but there are flashforwards, quick peeks and squints mostly into the immediate future(s), and they occur throughout the mission rather than at the beginning or the end.

Overall, The Future We Saw is an interesting take upon the heist and the post-cyberpunk roleplaying game, set in a tomorrow that we can already see.

Have a Safe Weekend

Friday Filler: Exploriana

In the nineteenth century there remained much of the world to be explored and discovered, so men and women would set out to chart and catalogue the great unknowns in Africa, Asia, and South America. Many would be sponsored by august bodies such as the Royal Geographical Society, the Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, and Société de Géographie, as well as many museums, and in turn the most successful of explorers would return with tales of their explorations, bringing back with them charts of where they have been, fantastic animals and beautiful plants, amazing treasures, and even lost explorers. They would go on to be famous, whilst their sponsors—the societies and the museums—would gain prestige, able to conduct greater scientific work and open greater exhibits to the public. This is the set-up for Exploriana, a board game of exploration and discovery, published by Triple Ace Games, following a successful Kickstarter campaign in which august scientific bodies will send out intrepid explorers and naturalists to chart and catalogue the world, and come back with great discoveries. Each player is the head of one these scientific bodies, who Recruits and sends out Explorers to the far flung corners of the world where they explore regions, and make and return with discoveries that the scientific organisations so covet. It combines ‘Card Drafting’, ‘Push Your Luck’, ‘Set Collection’, and ‘Worker Placement’ mechanics, is designed for between two and five players, aged fourteen and up, and takes roughly forty-five to sixty minutes to play.

In the nineteenth century there remained much of the world to be explored and discovered, so men and women would set out to chart and catalogue the great unknowns in Africa, Asia, and South America. Many would be sponsored by august bodies such as the Royal Geographical Society, the Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, and Société de Géographie, as well as many museums, and in turn the most successful of explorers would return with tales of their explorations, bringing back with them charts of where they have been, fantastic animals and beautiful plants, amazing treasures, and even lost explorers. They would go on to be famous, whilst their sponsors—the societies and the museums—would gain prestige, able to conduct greater scientific work and open greater exhibits to the public. This is the set-up for Exploriana, a board game of exploration and discovery, published by Triple Ace Games, following a successful Kickstarter campaign in which august scientific bodies will send out intrepid explorers and naturalists to chart and catalogue the world, and come back with great discoveries. Each player is the head of one these scientific bodies, who Recruits and sends out Explorers to the far flung corners of the world where they explore regions, and make and return with discoveries that the scientific organisations so covet. It combines ‘Card Drafting’, ‘Push Your Luck’, ‘Set Collection’, and ‘Worker Placement’ mechanics, is designed for between two and five players, aged fourteen and up, and takes roughly forty-five to sixty minutes to play.Fundamentally, Exploriana consists of five decks of cards and four boards. Three of the decks of cards are Region decks, consisting of Discovery cards, one each for Africa, Asia, and South America. Each Region deck has an associated Region board. The fourth board is the Renown/Score Track, whilst the fourth and fifth decks of cards consist of Explorer cards and Mission cards respectively. Each Discovery card in a Region deck indicates its type—Animal, Location, Treasure, Map, or Orchid, as well as the number of Victory Points it awards at game’s end, Renown for determining turn order, coins it awards, and potentially the Hazard it presented in acquiring. The three types of Hazard are ‘Wrong Turn’, ‘Animal Attack’, and ‘Rockfall’. If a player reveals the three different or three of the same Hazard types during a turn exploring, his turn is over. The three Region deck decks vary in terms of risk and reward, with South America having the lowest and Asia the highest.

The Explorer cards consist of individuals like the Entrepreneur who can draw new Mission cards and choose open to keep, the Medic who can turn over the top card of a Discovery deck and if has one, can ignore the Hazard it reveals, and the Photographer who can take two cards from a Region. Explorer cards are recruited in the first phase of each turn, but each has a cost to be paid if a player wants to use their effects, and an Explore card is discarded after use. Each Mission card has a task such as ‘My Hero!’ (rescuing three or more lost explorers), ‘Bloomin’ Marvelous!’ (collect a set of orchids, one of each type), and ‘Location, Location, Location!’ (collection a location from each of the three different Regions. Each Mission card awards four Victory Points.

Each of the three Region boards has spaces to place the players’ Explorer pawns and Lost Explorer tokens. They are also double-sided, one side being for two to four players and the other for five players. The Renown/Score Track is used to keep track of the players’ Renown throughout the game. Both Renown/Score Track and the three Region boards are designed to click together jigsaw fashion to form one long board.

Set-up of Exploriana is simple enough. The Renown/Score Track and the three Region boards are placed in a line down the table and the three Region decks shuffled and placed alongside them with three cards in reserve on one side and the rest on the other. Two cards from each deck are drawn and placed face up so that everyone can see them. Each player is given his two Explorer pawns, six coins, and two Missions, which will score them Victory Points if completed.

Each round of Exploriana consists of four phases. Turn order goes from the highest Renown to the lowest, but at the game’s beginning, the player who most recently travelled to another continent goes first. In the ‘Recruit Explorers’ phase, the players each choose one Explorer card from those face up. There is always one more Explorer card than the number of players and any Explorer card left has a coin added to it. A player who takes an Explorer card with coins on it, also gets the coins. This can be a consideration as players rarely have quite enough coins necessary to hire their Explorers and use their abilities. In the ‘Send Explorers’ phase, the players take in turns to assign one of their Explorer pawns, then the other, onto one or two of the Region boards. A player can only explore a Region deck if he has an Explorer pawn on the associated Region board. It is possible to completely fill the spaces on a Region board, forcing a player to place his Explorer pawn elsewhere.

Then, starting on the South America Region board and moving to the Africa Region board and then the Asia Region board, each player takes any number of actions for one of his Explorer pawns in the third phase, Explore Regions’, before going round again for each player’s second Explorer pawn. There are three types of action a player can take. First, he can ‘Explore’, turning over cards from the Region deck adjacent to Region board; second, he can ‘Hire a guide’, every player having a guide token he can use to cover a Hazard symbol on a face-up Region card, though this costs coins; and third, ‘Use an Explorer card’, a simple matter of following its instructions. A player’s turn with one Explorer pawn continues until one of four conditions are met. Either three different or three of the same Hazard types are revealed face-up on the Region cards, in which case the Explorer becomes lost and a random Lost Explorer token is added to the Region board and all of the face up Region cards in the Region are shuffled back into the Region deck, and two cards are drawn again. Lost Explorer tokens are worth two, three, or four Victory Points, and are placed face down. Either because there are five face-up Region cards adjacent to the Region board or the player decides to stop exploring, or because an Explorer card tells the player to stop.

If there are five face-up Region cards or the player decided to stop exploring, and there are not sufficient Hazard types revealed face-up to get the player lost, the last action he gets to do is ‘Take Picks’. If there are four or fewer Regions face-up to choose from, a player only gets one pick, but if there are five, he gets two. A pick can either be all of the Region cards with Animal symbols on them in the Region, a single Region card with a non-Animal symbol on it (Location, Treasure, Map, or Orchid), or a single Lost Explorer token on the Region Board. A player can then repeat this all with his second Explorer pawn, in either the same Region or a different one, depending upon where it is placed.

The fourth and last phase of a round is ‘End of the Round’. It is actually only triggered when any Region deck or its reserve pile, or the Explorer deck is depleted, and indicates the end of the game. Each player is awarded Victory Points for the number of Renown points scored, Mission cards completed, Lost Explorer tokens, coins, and Region cards with Location and Treasure symbols collected, for each Animal on their Region cards collected, the number of Map symbols collected, and the number of sets of Region cards with Orchid symbols collected. The player with the most Victory Points is the winner.

Essentially, each player is attempting to push his luck when exploring a Region and turning over its Region cards, attempting to find the Region cards he wants that will score him the most points or helps him fulfil the requirements of a Mission card. This is balanced against the possibility of too many Hazard symbols being revealed, and so making an Explorer lost, as well as the need to find coins which a player will need to pay in order to use the special ability of an Explorer card. The first player to any Region—typically dictated by Renown order—has the benefit of making use of the first two cards face-up in a Region, thematically, the equivalent of entering undiscovered territory. Later players will probably find that the face-up Region cards have changed, potentially with the best Region cards already having been picked or too many Region cards with Hazard symbols left to be revealed. The ‘Set Collection’ aspect of the game involves getting as many Region cards with Map symbols or sets of the three types of Orchid symbols on the Region cards. A last aspect of the game’s ‘Push Your Luck’ play, is whether or not to Explore the more dangerous Regions of Africa or Asia, which have higher rewards, but more risks in the form of a greater number of Hazard symbols.

Beyond the race to place Explorer pawns in choice slots on the Region boards, Exploriana is not a game with any real direct interaction between the players. This does not mean that it is a bad game however, rather that its competitive play is relatively gentle and probably suited to a younger audience than the minimum age of fourteen years old already given. Certainly twelve-year-olds would have no issue with relative complexities of Exploriana and those complexities are not that complex. Further, the playing time of forty-five minutes to an hour is a little long, except for the first playthrough perhaps. After that, it should play in thirty minutes or so.

That though, is the basic game. Exploriana includes much more than just the basic game. For two players, it adds a dummy third player to act as a rival, though this is not as enjoyable to play, and then there are several advanced rules and variants. These add valuable relics which can be discovered by collecting particular symbols for the Region the relic is from; a bonus of two coins for Explorer pawns which become lost, which encourages a player to actually push his luck even further exploring a Region and drawing cards; and Expansion cards which are taken as soon as they are drawn, such as the Poisoned Chalice which is given to another player (and later possibly to another player when an Explorer becomes lost) and losing the player who has it at the end of the game Victory Points. There are a total of nine advanced options and variants, which the players are free to pick and choose from, and that is in addition to the solo rules and variants included. Adding these to the play of the game will increase its play length though.

Physically, Exploriana is very well presented. A good cardstock is used for all of the cards, the playing pieces and tokens are of thick cardboard or wood, and everything is done in full colour. The rulebook is generally well written, but needs a careful read through in places.

Exploriana is quite a light game, with scope to make it as complex as the players want, but without getting overly so. Its engaging theme, attractive production values, and light mechanics make it a decent family game as well as something that can be enjoyed by the more experienced boardgamer too.

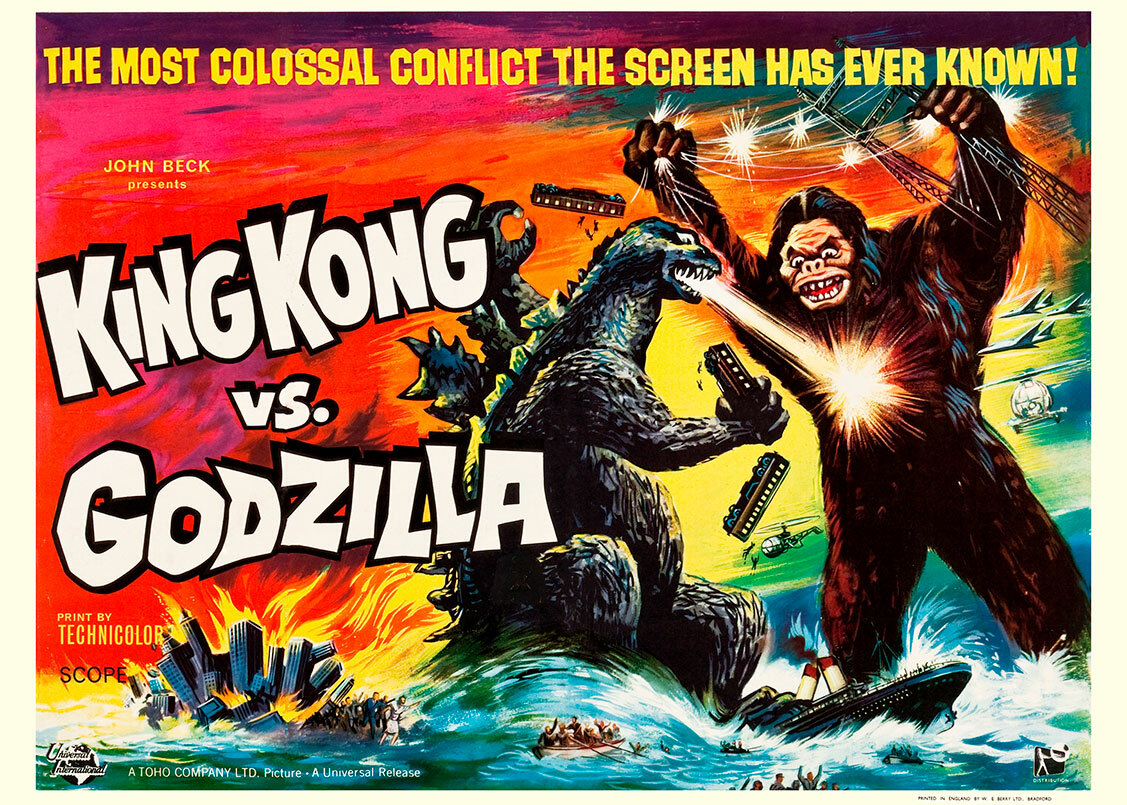

The Greatest Shōwa on Earth: 1962’s ‘King Kong vs. Godzilla’

Alex Adams / March 25, 2021

Ishiro Honda’s 1954 Godzilla is perhaps the most widely praised Kaiju film ever made. A special effects masterpiece at the time, the monochrome mother of all monster movies had bleak, fume-laden visuals, a gloomy, mournful tone, and an unambiguous anti-nuclear message. Even its conclusion, in which the pained Dr. Serizawa unleashes his hyper-toxic Oxygen Destroyer to finally rid Japan of its avenging lizard king, sees no redemption, as the weapon that banishes the beast also irreversibly poisons the Earth. Godzilla is rightly remembered as a serious, somber, and politically insightful cinematic monument with a powerful message and internationally historical significance. Its first dozen or so sequels, however, are quite another matter—a different beast, you could say.

For Godzilla would not remain an icon of manmade devastation for long. In the course of the next two decades, Godzilla would grow from a nightmarish God of Destruction into mankind’s dependable, child-friendly ally. “The dragon has become St. George,” wrote New York Times film critic Vincent Canby on the 1976 US release of Godzilla Vs. Megalon, in which Godzilla defends the Earth against the giant cockroach Megalon and his sinister ally, the buzzsaw-chested robot chicken Gigan. Godzilla’s role as the bane of modern Japan would be assumed by the many Kaiju successors he confronted, and the beast who had once embodied the apocalypse would now stand heroically between his antagonists and their desire to destroy the Earth.

Varying wildly in tone, the corpus of movies from the Shōwa era of the Godzilla series veers vertiginously between family-friendly entertainments—such as All Monsters Attack (1969), Son of Godzilla (1966), and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1964)—and the more adult tone evident in the environmentalist psychedelia of Godzilla Vs. Hedorah (1971) or the WrestleMania spectacles of Destroy All Monsters (1968) and Godzilla Vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). These movies are fondly remembered by fans for their rough and ready practical special effects, their cartoonish, preposterous pugilism, and their deliriously inventive storytelling, which could use anything at all as the pretext for a monster battle—from an insect invasion of the Earth to a 24-hour dance competition.

Nevertheless, their lack of the thematic seriousness and visual restraint so evident in Honda’s first film means that they are often looked down on as a silly dilution of the original movie, a goofy world cinema novelty of interest only to kids, nerds, or the sort of weirdo who used to load up on caffeine and stay up late to watch men in rubber suits wrestling on cheaply painted sound stages. Naturally I, as just such a weirdo, think that this sneering, while understandable, underplays a great deal of the sophistication and interest of these wacky, silly, excellently distracting films. Not simply the impoverishment of a once-grand icon in the pursuit of ever-dwindling box office returns (although Toho has certainly never been shy of ruthlessly commercially exploiting Godzilla), Godzilla’s evolution from cosmic punishment to benevolent savior also makes him one of the most interesting, flexible, and dynamic popular cultural icons of the Cold War years.

Rumble in the Jungle: King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)King Kong vs. Godzilla is perhaps the best remembered of the Shōwa-era Godzilla movies, after the original Godzilla. The first time either creature would be seen in color, it remains the most successful and popular Godzilla movie to this day, in terms of ticket sales at least, perhaps due to the way in which it was marketed—almost like a high-stakes boxing match or wrestling bout. The genius of its combination of two iconic monsters at a time when both of them still remained fearful beasts, rather than comic or heroic figures, was powerful enough for the movie to remain a genre high-water mark for years to come.

This double-headliner structure, in which two A-list monsters were brought together in order to double the appeal of the movie, would initiate a run of versus battles that would last for over a decade. From 1964 onwards, Toho produced at least one Godzilla movie every year until the financial failure of Terror of Mechagodzilla drew the franchise to a screeching halt in 1975. Though Godzilla had fought against the Ankylosaur Kaiju Anguirus seven years earlier in Godzilla Raids Again (1956), it would be King Kong Vs. Godzilla that truly cemented the formal template for the many monster clashes to come: on some pretext or other, Godzilla would face off against invading life forms from outer space, such as his arch-nemesis King Ghidorah, or against creatures with more Earthly origins, such as the mysterious and oddly beautiful Mothra, the sea-monster Ebirah, or, indeed, the American myth King Kong.

At the same time as it is great knockabout fun at face value, the “versus movie” format also provides a tremendously flexible and rich conceptual palette for filmmakers to engage with social and political ideas. In his extraordinary book of mini-essays Mythologies (1957), French critic Roland Barthes observes that amateur wrestling is a kind of broad-brush theater in which good and evil battle for symbolic supremacy. “In the ring,” he writes, “wrestlers remain gods because they are, for a few moments, the key which opens Nature, the pure gesture which separates Good from Evil, and unveils the form of a Justice which is at last intelligible.” The very simplicity and crudeness of the drama, he writes, is what makes these bouts transcendent. Further, he claims, its ramshackle nature—and the foundational role of the audience’s gleeful suspension of disbelief—also means that its value as symbolic play is brought to the forefront: “There is no more a problem of truth in wrestling than in the theatre. In both, what is expected is the intelligible representation of moral situations.”

So it is in the Kaiju clash film, that unique brand of spectacle cinema that shares many formal and thematic traits with wrestling as well as other Japanese cultural forms such as anime and manga. The bold, lurid language of gesture, the vivid play of symbol and myth, and their open environmentalist and anti-nuclear ethical commitments make them a kind of powerful moral theater, at once sublime and ridiculous, at once ostentatiously silly and deathly serious. Crucially, it is equally redundant to point out that the special effects are unconvincing in King Kong Vs. Godzilla as it is to point out that wrestling is “not real” or that a play is made up (or indeed, that your Extreme Noise Terror record features a lot of shouting—what exactly did you expect?). What matters is not verisimilitude, or even a coherently sequential narrative, but the experience of grand moments of sensory power, scenes of epic destruction and wrenching pathos, and the realization of overwhelming visions of primal, fantastical worlds previously not imaginable.

You don’t, after all, go to a film about wrestling monsters expecting subtlety. But this doesn’t mean, of course, that they are without content. Even the original Godzilla derives its power from its total commitment to the enactment of one broad, bold idea.

The Meaning of MonstrosityToho’s first Godzilla film had such a potent social and political message that the creature would always be thought of in semiotic terms, always interpreted as a metaphor for the pressing concerns of the time. The subsequent Shōwa films, though, are chaotically flexible in this regard, and Godzilla cannot be read consistently as any kind of fixed or coherent symbol from film to film. More often, it is his foes who “embody” some social or political force against which the Earth needs to be defended, whether it is arms-race militarism (Mechagodzilla), pollution (Hedorah), renewed atomic testing (Megalon), or intergalactic imperialism (King Ghidorah, Gigan). Most of all, though, in his initial incarnation at least, Godzilla represents the unstoppable force, the mute, brute power of nature, the principle of sheer indestructibility.

This characterization of Godzilla remains, for many, the most compelling. Shusuke Kaneko, director of Millennium-era fan favorite Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001), famously commented that Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Hollywood interpretation of Godzilla was disappointing in part because of its fear of American ordnance. “Americans seem unable to accept a creature,” he said, “that cannot be put down by their arms.” (Rather than an adaptation of the Toho legend of the mysterious force of nature, Emmerich’s version recalls nothing more than the climax of the previous year’s Jurassic Park: The Lost World, in which a T-Rex runs amok in San Diego.) Godzilla is at his most attractive when he is at his ugliest, when he embodies a total disaster that can be momentarily deflected but never truly defeated.

In “Mammoth,” the 74th essay in Minima Moralia (1951), Theodor Adorno writes that “the desire for the presence of the most ancient is a hope that animal creation might survive the wrong that man has done it, if not man himself, and give rise to a better species, one that finally makes a success of life.” Adorno’s reflections on the appeal of prehistoric beasts have more than a little relevance to Toho’s reptilian colossus. Very often Godzilla is conceived of as the resistance or revenge of the natural world, an embodiment of nature’s apocalyptic judgement upon mankind, a kind of demonic scourge unleashed by the obscure yet vengeful conscience of the wronged planet. He retains this character in King Kong Vs. Godzilla—when he bursts out of an iceberg at the start of the movie, nobody is pleased that he has arisen from his slumber to save the day, as would happen in later films. Here, he is a wild, unpredictable cataclysm that cannot be stopped, a symbol of the natural world’s dominance over us and its indifferent ability to survive us.

Kong, too, is no stranger to social and political interpretations. There is a long and distinguished critical tradition of reading King Kong as a problematic and racist engagement with themes related to slavery, imperialism, and moral panics about Black masculinity and sexuality. Merian C. Cooper’s 1933 original, which draws heavily on the representational traditions of lost world adventure fiction, is widely considered to be an allegory of slavery and imperial exploitation, a tragic parable of man’s ruthless, irreverent, and self-involved abuse of the world’s majestic wildness. John Guillermin’s 1976 US version would more explicitly locate the story in the context of petropolitics, as the colonizing expedition to Skull Island is motivated not by a desire to capture a mythic beast but, more prosaically perhaps, to drill for oil. When Peter Jackson remade the movie in 2005, he made it a satire of the entertainment industry, casting Carl Denham as a roguish, self-destructive genius, an Orson Welles figure whose visionary talent threatens to destroy all of those near to him, and whose pledges to complete his work in the honor of the people who died in its course recalls the increasingly desperate dedications of documentarian-cum-unintentional-murderer Remy in 1992’s Man Bites Dog. For Jackson, Denham is like Kong, an unstoppable and doomed force of nature who destroys by loving.

Every Hollywood version of the original story, though, however sophisticated, simultaneously exploits the persistent racist panic about Black male desire for white women that is embedded into the fabric of the story. King Kong is, at its heart, a story about the violent death that inevitably looms at the horizon of Kong’s love for human women, a fable that has always been read as a racist allegory of the tragedy and illegitimacy of Black men’s supposedly insatiable appetite for the love of white women.

King Kong Vs. Godzilla is no exception here, as Kong’s storyline fuses critique of corporate colonialism with a problematic representation of Black desire. The characters’ extractivist plunder of Kong’s home island—changed from the enigmatic and unlocatable Skull Island to Pharaoh Island, a fictionalized landmass among the Solomon Islands—is the incident that prompts the confrontation between the two legendary beasts, and the Pacific Pharmaceutical execs who exploit Pharaoh Island for its pleasantly intoxicating fruit are shown as single-minded, hubristic buffoons as they capture Kong with the insane intent of using him to advertise their company. The clash of titans still makes time for a comedic critique of the ruthlessness of the capitalist advertising industry; so too does it retain Kong’s fascination with human women, as he scales a government building while clinging to a beautiful young woman he has captured.

The natives of Skull Island, too, are always a problem for these films. From Cooper’s original painted tribe of Kong-worshippers, to Jackson’s violent brutes (who recall the Uruk-Hai orcs from his Lord of the Rings trilogy), to the noble savages of 2017’s Kong: Skull Island (who recall Kurtz’s sinister and silent tribe in 1979’s Apocalypse Now), the human inhabitants of Kong’s home are routinely represented in extraordinarily dehumanizing ways.

Once again, King Kong Vs. Godzilla follows suit. The tribe of Faro Island is portrayed by actors in full-body blackface, and the Pacific Pharmaceutical employees bribe them with a transistor radio and tobacco. This patronizing bargain, in which they steal the island god in return for habit-forming poison and toys, is part of the film’s critique of exploitative capitalism; it is also, however, played for laughs. No matter how progressive the themes, a film that features dehumanizing ridicule like this is irredeemably racist. It is interesting, too, that the first major development in the Godzilla franchise’s relationship with its US audience foregrounds anti-Black racism, as though one of the safe territories on which the US and Japan could rebuild their relationship was the imperialist dehumanization of Black people.

For King Kong vs. Godzilla is historically and politically significant most of all because it was an international co-production between Japanese and American filmmakers. Where the original Godzilla is a fable of the nuclear suffering that the US inflicted upon Japan, made only two years after the conclusion of the post-war American occupation, King Kong vs. Godzilla is a symbol (and product) of the renewed Pacific alliance and the reestablishment of geopolitical cooperation between the US and Japan. Ishiro Honda returned to direct the original Japanese version for Toho, released in 1962, and John Beck helmed the adaptation of the US version for Universal Pictures, which was released the following year. This collaboration would fuel a monster movie franchise that endures today.

“This is UN reporter Eric Carter with the news”Prior to Emmerich’s 1998 adaptation, every time a Godzilla movie appeared in Western markets it would be bowdlerized in some way. The movies were often retitled, recut, or given comically bad English dubbing; some of them, such as the original Godzilla and Godzilla 1985, were reshot, with American stars retroactively given focalizing roles in order, it was thought, to make the films more appealing to American and European audiences. Many of the recuts were extraordinarily unforgiving—the NBC screening of Godzilla vs. Megalon, for example, savagely streamlined the movie down to just 48 minutes, cutting out almost half of the movie in order to accommodate commercials and a Godzilla-suited John Belushi’s accompanying skits.

King Kong vs. Godzilla is unique in the way it is recut. A great deal of Honda’s original is brusquely shaven off and replaced, not with dramatic scenes featuring American actors, but with newscast-style footage of a reporter, Eric Carter, explaining the events of the plot directly to the audience. There is an amusing irony here: in the Japanese version, Pacific Pharmaceutical needs to use Kong for advertising because their own TV show is “dull, boring, and without imagination.” Carter’s broadcasts are almost as dry as the output of Pacific Pharmaceutical’s fictional TV network, as clumsily direct and awkwardly literal an expository device as you are ever likely to see in any film. Carter, the voice of the movie, is the antithesis of “show, don’t tell,” sometimes dictating not only the events but the way we should feel about them, too.

This clunkily oratorical exposition may be dramatically flat, but it has the virtue at least of being swift. One of the enduring problems of the Shōwa Godzilla series is the grinding slowness of some of the utterly turgid exposition, so it is in a way gratifying for an audience to be simply given the facts rather than having to yawn through interminable dialogue. And Carter’s scenes are also, sometimes, wonderfully comic. The scene in which he invites a paleontological expert into the studio to explain Godzilla’s origins and anatomy, for instance, features this expert—purportedly from New York University—using a child’s illustrated guide to dinosaurs as a visual aid.