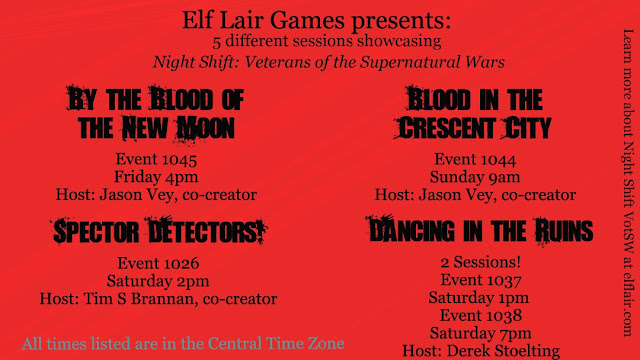

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko – A City Adventure Supplement for Labyrinth Lord

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko – A City Adventure Supplement for Labyrinth Lord details a borderlands city where life takes a strange fever-dream cast, where confidence tricks and scams are an accepted way of life, where its each of four contradas—or quarters—worships one of the four gods (and pointedly ignores the fifth) entombed in the squat, black bulk of the Tomb of the Town Gods, and where adventurers can find respite, relaxation, rumours, and more from the wilderness beyond… It stands amidst the Greater Marlinko Canton in the world of Zěm—as detailed in

What Ho, Frog Demons! – Further Adventures in Greater Marlinko Canton, not too far from the

Slumbering Ursine Dunes, and from there,

Misty Isles of the Eld. It is published by

Hydra Collective LLC and is an Old School Renaissance setting supplement designed to be run using Goblinoid Games’

Labyrinth Lord. Of course, it can easily be adapted to the Retroclone of the Game Master’s choice.

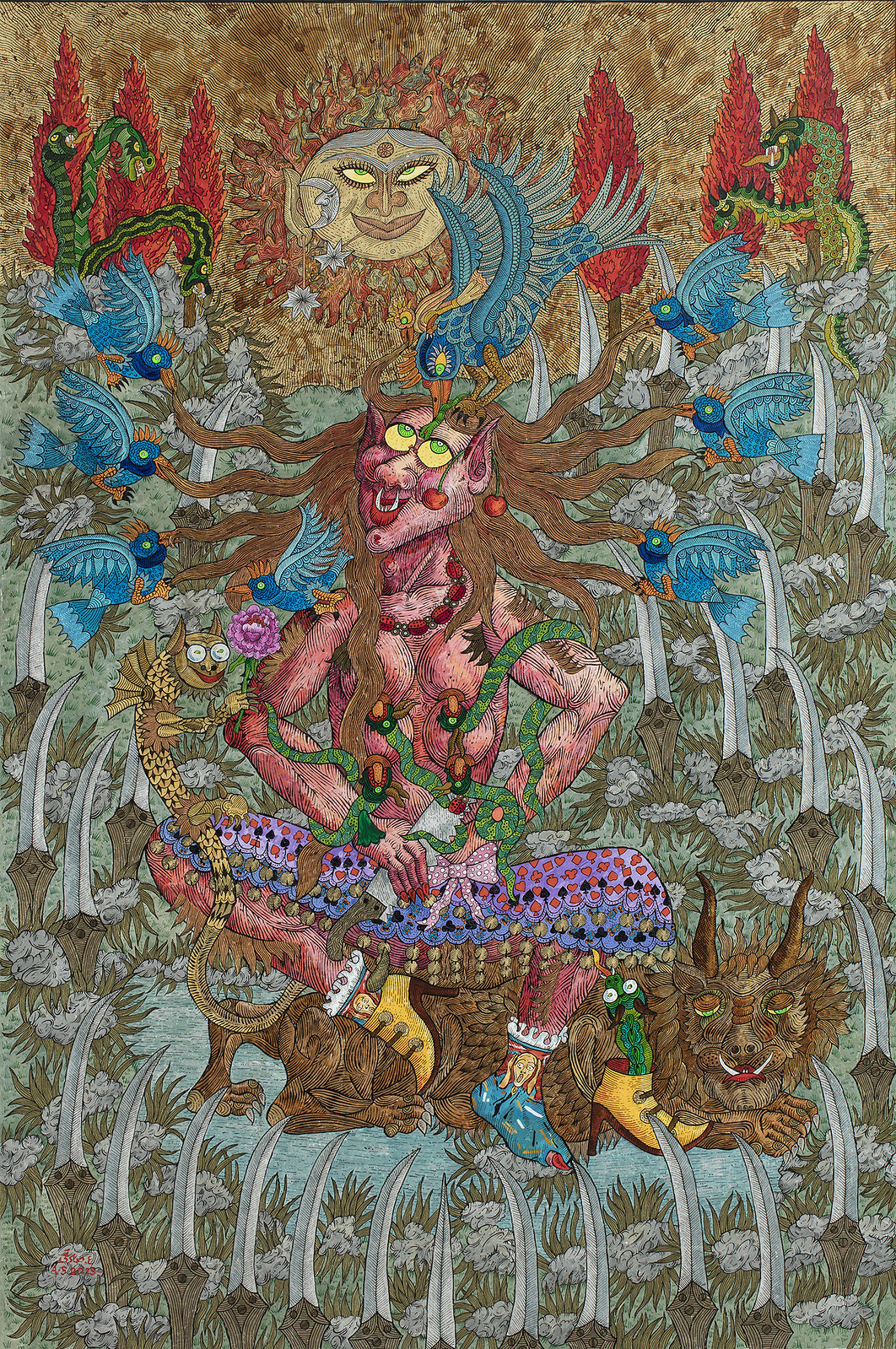

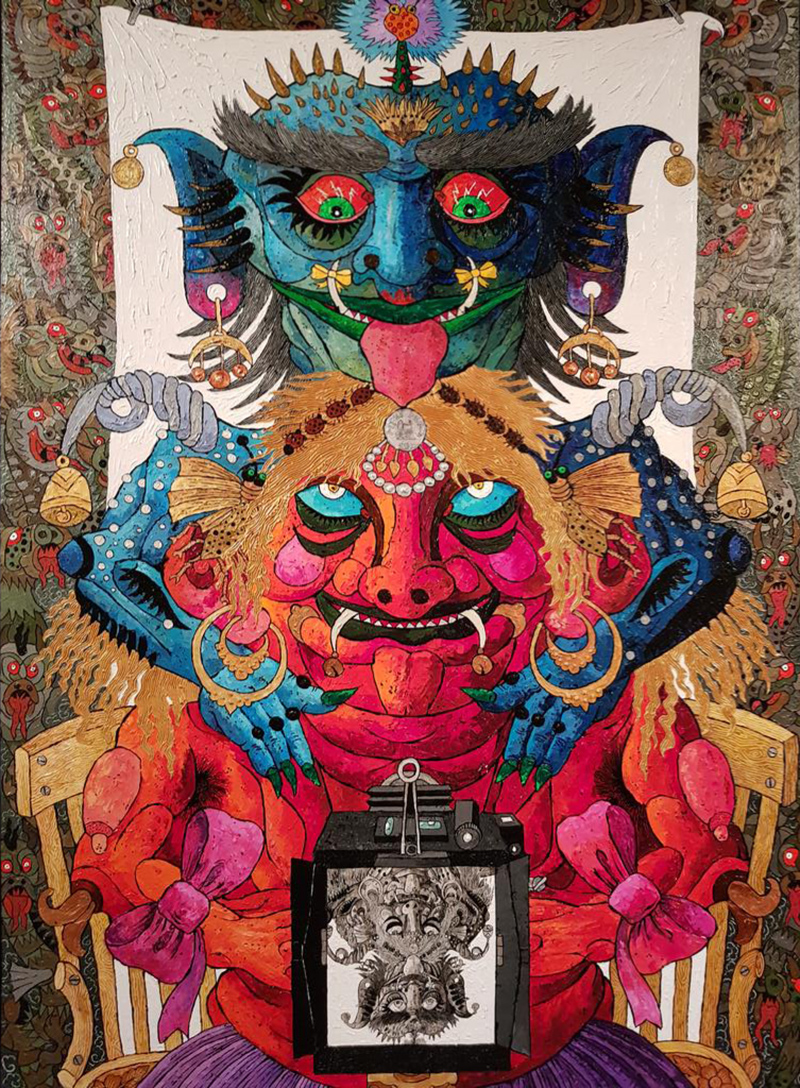

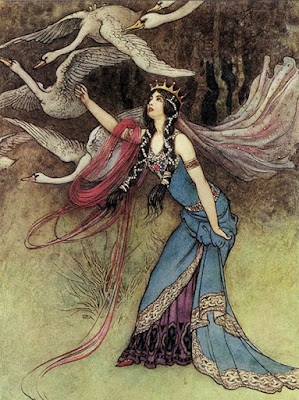

As a city located in the Hill Cantons, a region described as, “A Slavic-myth inspired, acid fantasy world of Moorcockian extradimensional incursions and Vancian swindlers and petty bureaucrats.”, Marlinko matches much of that description. Both of its four contradas and their inhabitants have Slavic names and many of its monsters are drawn from Slavic legend. For example, one of the city’s leading socialites is Lady Szara, organiser of the annual Bathe in the Blood of your Servants charity ball, is secretly an ancient and evil strigoi—a Romanian version of the vampire—who it is suggested, should speak in the style of the actress, Zsa Zsa Gabor, only more sinister. She may even employ the Player Characters to locate certain magical gewgaws and knick-knacks, that is, if she simply does not decide to consume them... The Eld—essentially ‘space elves’ from another dimension with a distinctly Melnibonéan-like, decadent sensibility—slink secretly into the city, and the bureaucracy extends to unions, such as The Guild of Condottiere, Linkboys, Roustabouts, and Stevedores, a union for adventuring party hirelings, which really objects to scab hirelings! Numerous swindlers and scam artists are mentioned throughout the description of the city, and there is even a section on ‘Running Long and Short Cons’.

Intended to be regularly visited by Player Characters of Second and Third Levels, what

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko – A City Adventure Supplement for Labyrinth Lord is not, is a traditional city supplement. There is no building-by-building description, no great history of the city, or great overview. Instead, it focuses on the pertinent details about four contradas and the things that can be found there and more importantly, can be interacted with by the Player Characters. Včelar is home to Marlinko’s wealthy, dominated by their great painted-plastered town-manses and famed for Jarek’s Manse and Tiger Pit where the perpetually name dropping and bragging owner has built a domed all-weather tiger pit in which he stages tiger wrestling! Obchodník is the city’s business district, where at Fraža’s Brokerhouse, the Player Characters might make purchases from the radically—for Marlinko, that is—honest and unfortunately terribly racist, Fraža the Curios Dealer, or pay for at fortune at The Serene Guild of Seers, Augurs, Runecasters, and Wainwrights—the clarity (at least) of any such fortune depending on the cost. Svině is home to Marlinko’s slums, but also many guilds, such as The Illustrious Workers of Wood or The Guild of Condotierre, Linkboys, Roustabouts and Stevedores’ Dome of Supernal Dealings, but also home to the Catacombs of St. Jack’s Church of the Blood Jesus, whose disturbingly bloody misinterpretations of Christianity has the potential to unleash murderous mayhem upon the city. Soudce is home to the city’s suburbs, their skyline dominated by the Onion Tower of the Checkered Mage, the home of the city’s resident arch-mage, František, a surprisingly level-headed wizard, who might pay well for certain items.

Each of the four contradas is accompanied by a table of random encounters, a mixture of the mundane, the silly, and the weird. For example, a group of flirts who if a Player Character parties with might wake up the next morning at his own shotgun wedding; Kytel the Duellist, a thoroughly bored swordmaster who will fight anyone to first blood; Old Slinky Panc, an escaped tiger, probably drugged and quite harmless, who Jarek the Nagsman would probably want returned—and returned unharmed; and a Hairless Hustler who will offer to sell the Player Characters two bars of surprisingly warm to the touch silver metal—and there is a reason that the Hairless Hustler lacks hair… These are all engaging encounters which make getting about the city memorable and interesting, some of them having the capacity to turn into interesting adventures depending upon the actions of the Player Characters.

Marlinko’s notables are described in some detail, but perhaps the best part of their descriptions are the suggestions on how to speak like them. The Game Master should have enormous fun portraying any one of them. In comparison, only two adventure sites are detailed in Fever-Dreaming Marlinko—‘Lady Szara’s Town-Manse’ and ‘Catacombs of the Church of the Blood Jesus’. Ultimately, they are both places to raid and ransack, home to respective evils present in the city, but not raid and ransack without reason. A Player Character might be kidnapped and find himself locked up in the catacombs first or the Player Characters all together might be hired to find a missing person, whilst Lady Szara could hire the Player Characters rather than give them cause to attack her and so have them visit her home. Of the two, ‘Lady Szara’s Town-Manse’ is the more interesting and the more thoughtful in its design, being an actual home rather than just another monster lair. It is also better mapped.

Beyond describing might be found in each contrada,

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko details crime—sanctioned and unsanctioned crime—and punishment in the city, advice on running cons in the city, and buying and selling in the city—everything from War Ocelots and Radegast’s Dark ale to the Poignard of the Overworld and a campy, faux-barbarian meadhall. Emphasising Marlinko as a place to visit and unwind in its taverns and other entertainment establishments,

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko includes a guide to carousing in the city and potential outcomes whichever contrada the Player Characters are visiting. There are even three locations for the Labyrinth Lord to expand as potential adventure sites, though of course, it would be nice to have had more ready-to-play adventure sites in the book.

However, as odd and as weird as the city of Marlinko is, it can get weirder. As with the other titles set in the Hill Cantons,

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko has a Chaos Index, which tracks the ebb and flow of the weirdness in the city, much of it being driven by the actions of the Player Characters, including making trips back and forth to the Slumbering Ursine Dunes. This is indicative of the design of

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko, that it is ideally meant to be played in tandem with

Slumbering Ursine Dunes. As the weirdness factor grows, the cultists of the Church of the Blood Jesus might commit more, and bloodier murders, mass hallucinations might break out, hundreds participate in a group wedding, and more. The weirdness factor also affects the ‘News of the Day’, the rumours and truths which spread throughout the city.

Rounding out

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko is a set of five appendices. The first is a bestiary which adds three monsters—the Robo-Dwarf, the Wobbly Giant, and the Cantonal Strigoi, whilst the second, a ‘Tiger Wrestling Mini-Game’, provides the rules for handling events at Jarek’s Manse and Tiger Pit, the only tiger-wrestling arena in town. It is definitely a dangerous pastime, but good luck to any Player Character who throws his hat into the ring! Two new Classes are detailed in the third appendix. The Mountebank is a Thief-subclass which has the Sleight-of-Hand skill for moving and switching out objects as part of a scam, can use Illusionist spells—though they can only be learned by swindling them out of actual Illusionists, and even temporarily raise their Charisma to eighteen! The other Class is the Robo-Dwarf, which is more of a strange mechanical variant upon the actual Dwarf Class. The last two appendices provide the Labyrinth Lord with a useful list of ‘Common NPC names and Nicknames’ and a pronunciation guide.

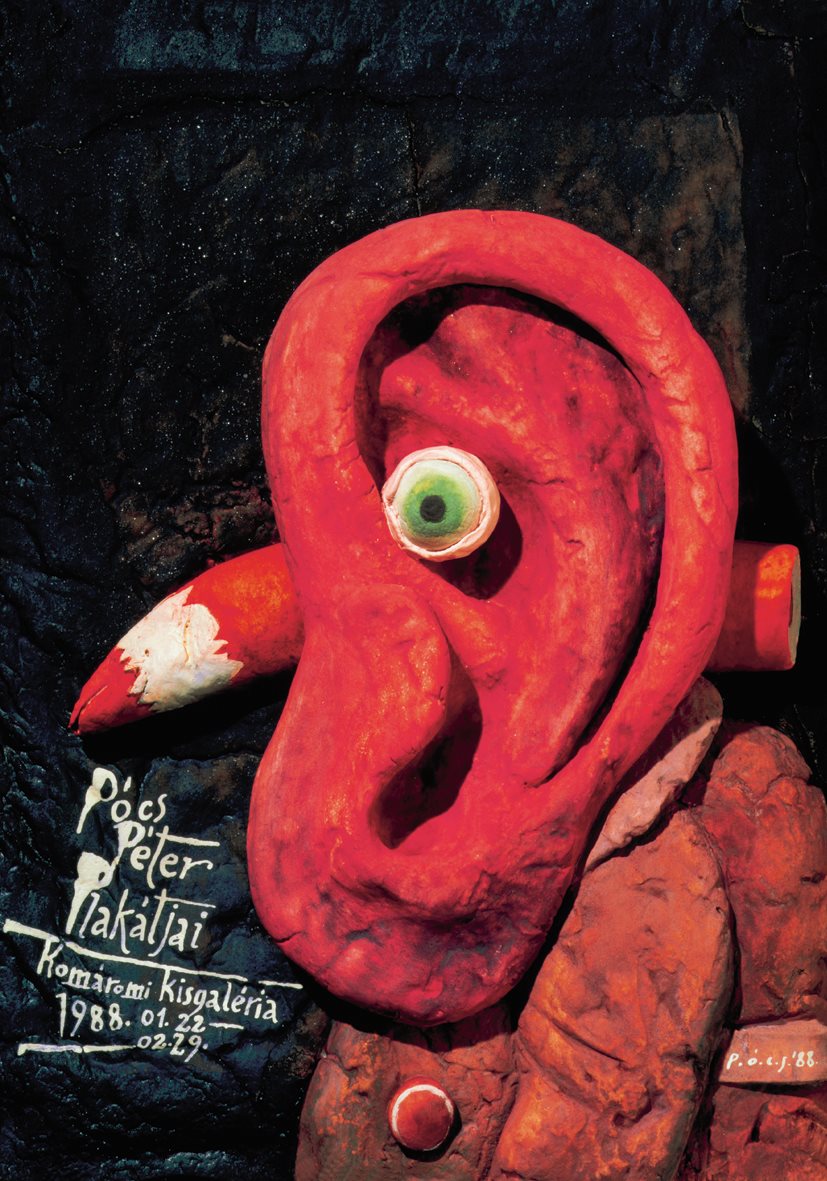

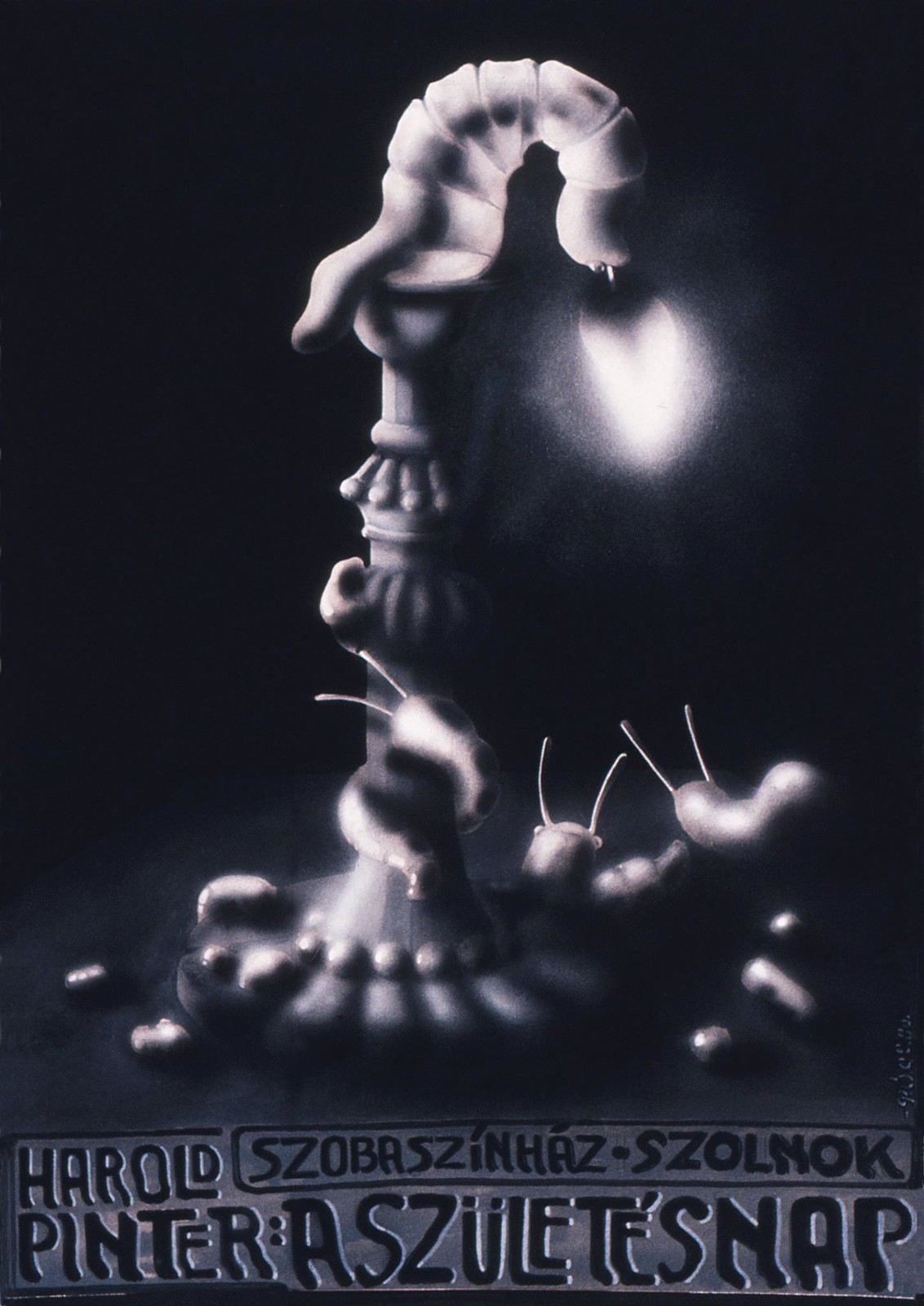

Physically,

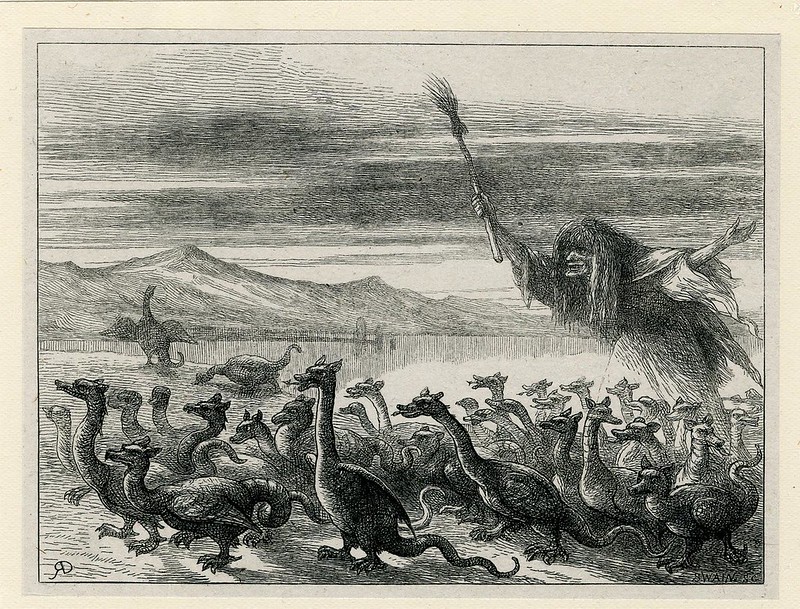

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko is generally well laid out, the writing is clear, and the artwork is excellent. It needs an edit in places, the real problem with the physical book is that it is not well organised, lacking an introduction which would help the Labyrinth Lord understand how the city functions as a game setting and the order in which the book’s contents come not always in the right place. Once the Labyrinth Lord has read through the book, it is relatively easy to grasp how the city works as a setting.

Apart from the less than useful organisation, there are really only one or two other issues with

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko—both of which could cause offence. The first is that St. Jack’s Church of the Blood Jesus is a potentially offensive misinterpretation of Christianity, whilst the second is that one or two of the NPCs are described as fervent racists and that the Labyrinth Lord is expected to portray this in character. Now this does take place in a fantasy world, but that does not mean that neither a player nor the Labyrinth Lord cannot or should be necessarily comfortable about this. This is one aspect of the setting which will require a discussion between all of the players before play begins to see whether they are prepared to accept it or not as part of the setting. The likelihood is not and the Labyrinth Lord should be prepared to replace it with potentially less offensive character quirks or attitudes for the NPCs concerned.

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko is designed as campaign base, one which the Player Characters will return to again and again after exploring first the Slumbering Ursine Dunes, then the Misty Isles of the Eld, and from there, the wider world of Zěm as detailed in

What Ho, Frog Demons! – Further Adventures in Greater Marlinko Canton. Although the Labyrinth Lord could use it in another setting, it does work best with those other books. And each time the Player Characters visit Marlinko, the Labyrinth Lord is given the means to make that visit memorable—with locations they might want to go to, random encounters which can become something more, rumours, and eventually weird things going on around them. There is no part of Marlinko as described which cannot be interacted with or does not add to the sense of oddness which pervades the city and which will probably be worse with every visit. Overall,

Fever-Dreaming Marlinko – A City Adventure Supplement for Labyrinth Lord is a brilliantly written, incredibly gameable setting supplement which provides the Labyrinth Lord with an excellent toolkit to bring a fantastical city setting to life.