Alex Adams / March 25, 2021

Ishiro Honda’s 1954 Godzilla is perhaps the most widely praised Kaiju film ever made. A special effects masterpiece at the time, the monochrome mother of all monster movies had bleak, fume-laden visuals, a gloomy, mournful tone, and an unambiguous anti-nuclear message. Even its conclusion, in which the pained Dr. Serizawa unleashes his hyper-toxic Oxygen Destroyer to finally rid Japan of its avenging lizard king, sees no redemption, as the weapon that banishes the beast also irreversibly poisons the Earth. Godzilla is rightly remembered as a serious, somber, and politically insightful cinematic monument with a powerful message and internationally historical significance. Its first dozen or so sequels, however, are quite another matter—a different beast, you could say.

For Godzilla would not remain an icon of manmade devastation for long. In the course of the next two decades, Godzilla would grow from a nightmarish God of Destruction into mankind’s dependable, child-friendly ally. “The dragon has become St. George,” wrote New York Times film critic Vincent Canby on the 1976 US release of Godzilla Vs. Megalon, in which Godzilla defends the Earth against the giant cockroach Megalon and his sinister ally, the buzzsaw-chested robot chicken Gigan. Godzilla’s role as the bane of modern Japan would be assumed by the many Kaiju successors he confronted, and the beast who had once embodied the apocalypse would now stand heroically between his antagonists and their desire to destroy the Earth.

Varying wildly in tone, the corpus of movies from the Shōwa era of the Godzilla series veers vertiginously between family-friendly entertainments—such as All Monsters Attack (1969), Son of Godzilla (1966), and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1964)—and the more adult tone evident in the environmentalist psychedelia of Godzilla Vs. Hedorah (1971) or the WrestleMania spectacles of Destroy All Monsters (1968) and Godzilla Vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). These movies are fondly remembered by fans for their rough and ready practical special effects, their cartoonish, preposterous pugilism, and their deliriously inventive storytelling, which could use anything at all as the pretext for a monster battle—from an insect invasion of the Earth to a 24-hour dance competition.

Nevertheless, their lack of the thematic seriousness and visual restraint so evident in Honda’s first film means that they are often looked down on as a silly dilution of the original movie, a goofy world cinema novelty of interest only to kids, nerds, or the sort of weirdo who used to load up on caffeine and stay up late to watch men in rubber suits wrestling on cheaply painted sound stages. Naturally I, as just such a weirdo, think that this sneering, while understandable, underplays a great deal of the sophistication and interest of these wacky, silly, excellently distracting films. Not simply the impoverishment of a once-grand icon in the pursuit of ever-dwindling box office returns (although Toho has certainly never been shy of ruthlessly commercially exploiting Godzilla), Godzilla’s evolution from cosmic punishment to benevolent savior also makes him one of the most interesting, flexible, and dynamic popular cultural icons of the Cold War years.

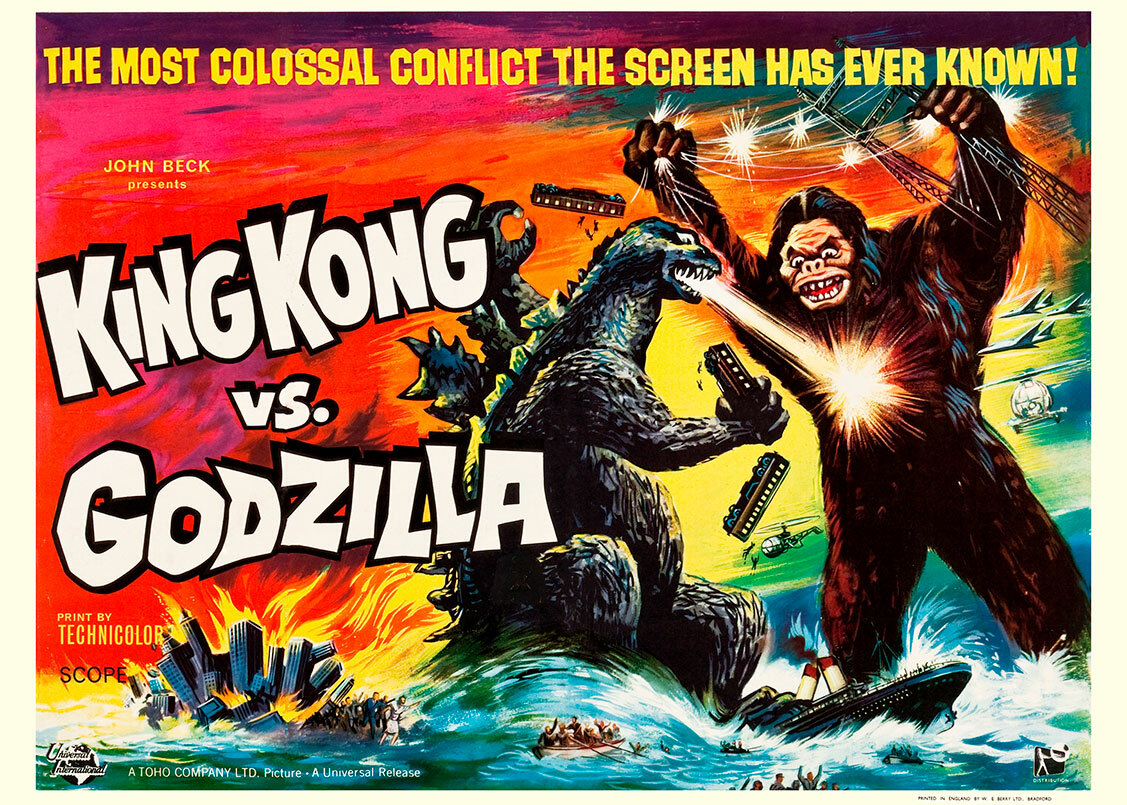

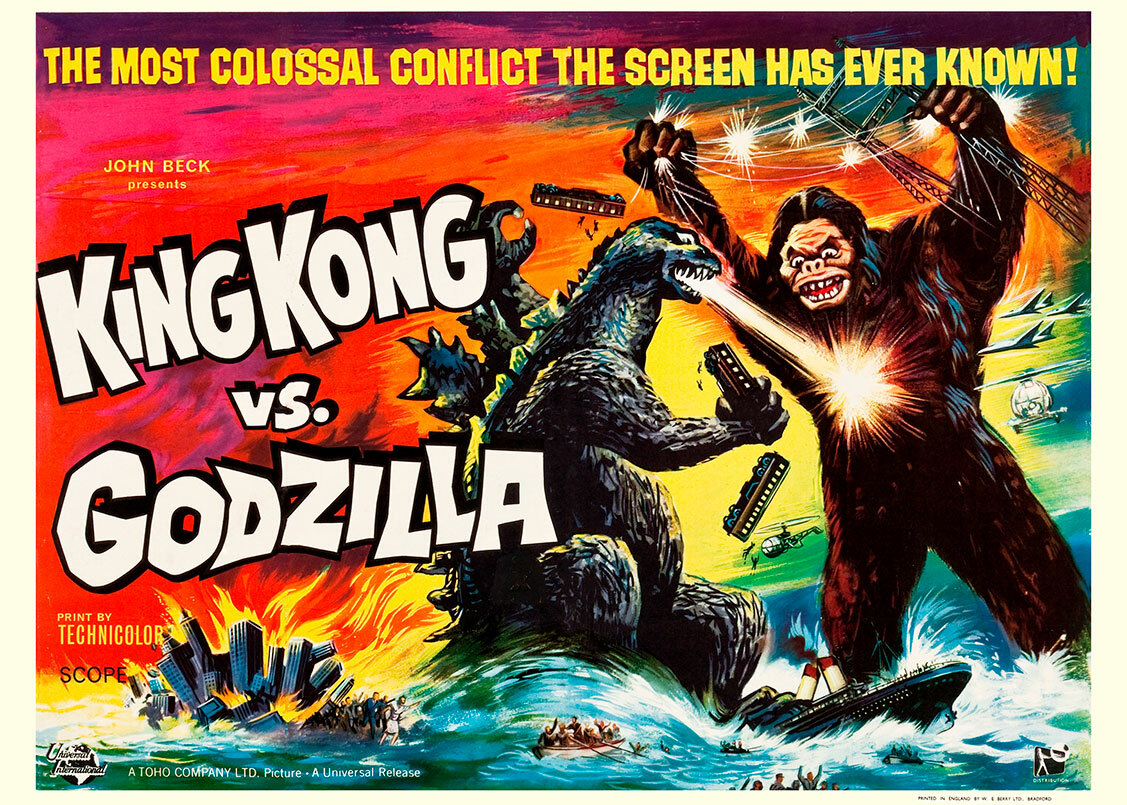

Rumble in the Jungle: King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

King Kong vs. Godzilla is perhaps the best remembered of the Shōwa-era Godzilla movies, after the original Godzilla. The first time either creature would be seen in color, it remains the most successful and popular Godzilla movie to this day, in terms of ticket sales at least, perhaps due to the way in which it was marketed—almost like a high-stakes boxing match or wrestling bout. The genius of its combination of two iconic monsters at a time when both of them still remained fearful beasts, rather than comic or heroic figures, was powerful enough for the movie to remain a genre high-water mark for years to come.

This double-headliner structure, in which two A-list monsters were brought together in order to double the appeal of the movie, would initiate a run of versus battles that would last for over a decade. From 1964 onwards, Toho produced at least one Godzilla movie every year until the financial failure of Terror of Mechagodzilla drew the franchise to a screeching halt in 1975. Though Godzilla had fought against the Ankylosaur Kaiju Anguirus seven years earlier in Godzilla Raids Again (1956), it would be King Kong Vs. Godzilla that truly cemented the formal template for the many monster clashes to come: on some pretext or other, Godzilla would face off against invading life forms from outer space, such as his arch-nemesis King Ghidorah, or against creatures with more Earthly origins, such as the mysterious and oddly beautiful Mothra, the sea-monster Ebirah, or, indeed, the American myth King Kong.

At the same time as it is great knockabout fun at face value, the “versus movie” format also provides a tremendously flexible and rich conceptual palette for filmmakers to engage with social and political ideas. In his extraordinary book of mini-essays Mythologies (1957), French critic Roland Barthes observes that amateur wrestling is a kind of broad-brush theater in which good and evil battle for symbolic supremacy. “In the ring,” he writes, “wrestlers remain gods because they are, for a few moments, the key which opens Nature, the pure gesture which separates Good from Evil, and unveils the form of a Justice which is at last intelligible.” The very simplicity and crudeness of the drama, he writes, is what makes these bouts transcendent. Further, he claims, its ramshackle nature—and the foundational role of the audience’s gleeful suspension of disbelief—also means that its value as symbolic play is brought to the forefront: “There is no more a problem of truth in wrestling than in the theatre. In both, what is expected is the intelligible representation of moral situations.”

So it is in the Kaiju clash film, that unique brand of spectacle cinema that shares many formal and thematic traits with wrestling as well as other Japanese cultural forms such as anime and manga. The bold, lurid language of gesture, the vivid play of symbol and myth, and their open environmentalist and anti-nuclear ethical commitments make them a kind of powerful moral theater, at once sublime and ridiculous, at once ostentatiously silly and deathly serious. Crucially, it is equally redundant to point out that the special effects are unconvincing in King Kong Vs. Godzilla as it is to point out that wrestling is “not real” or that a play is made up (or indeed, that your Extreme Noise Terror record features a lot of shouting—what exactly did you expect?). What matters is not verisimilitude, or even a coherently sequential narrative, but the experience of grand moments of sensory power, scenes of epic destruction and wrenching pathos, and the realization of overwhelming visions of primal, fantastical worlds previously not imaginable.

You don’t, after all, go to a film about wrestling monsters expecting subtlety. But this doesn’t mean, of course, that they are without content. Even the original Godzilla derives its power from its total commitment to the enactment of one broad, bold idea.

The Meaning of Monstrosity

Toho’s first Godzilla film had such a potent social and political message that the creature would always be thought of in semiotic terms, always interpreted as a metaphor for the pressing concerns of the time. The subsequent Shōwa films, though, are chaotically flexible in this regard, and Godzilla cannot be read consistently as any kind of fixed or coherent symbol from film to film. More often, it is his foes who “embody” some social or political force against which the Earth needs to be defended, whether it is arms-race militarism (Mechagodzilla), pollution (Hedorah), renewed atomic testing (Megalon), or intergalactic imperialism (King Ghidorah, Gigan). Most of all, though, in his initial incarnation at least, Godzilla represents the unstoppable force, the mute, brute power of nature, the principle of sheer indestructibility.

This characterization of Godzilla remains, for many, the most compelling. Shusuke Kaneko, director of Millennium-era fan favorite Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001), famously commented that Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Hollywood interpretation of Godzilla was disappointing in part because of its fear of American ordnance. “Americans seem unable to accept a creature,” he said, “that cannot be put down by their arms.” (Rather than an adaptation of the Toho legend of the mysterious force of nature, Emmerich’s version recalls nothing more than the climax of the previous year’s Jurassic Park: The Lost World, in which a T-Rex runs amok in San Diego.) Godzilla is at his most attractive when he is at his ugliest, when he embodies a total disaster that can be momentarily deflected but never truly defeated.

In “Mammoth,” the 74th essay in Minima Moralia (1951), Theodor Adorno writes that “the desire for the presence of the most ancient is a hope that animal creation might survive the wrong that man has done it, if not man himself, and give rise to a better species, one that finally makes a success of life.” Adorno’s reflections on the appeal of prehistoric beasts have more than a little relevance to Toho’s reptilian colossus. Very often Godzilla is conceived of as the resistance or revenge of the natural world, an embodiment of nature’s apocalyptic judgement upon mankind, a kind of demonic scourge unleashed by the obscure yet vengeful conscience of the wronged planet. He retains this character in King Kong Vs. Godzilla—when he bursts out of an iceberg at the start of the movie, nobody is pleased that he has arisen from his slumber to save the day, as would happen in later films. Here, he is a wild, unpredictable cataclysm that cannot be stopped, a symbol of the natural world’s dominance over us and its indifferent ability to survive us.

Kong, too, is no stranger to social and political interpretations. There is a long and distinguished critical tradition of reading King Kong as a problematic and racist engagement with themes related to slavery, imperialism, and moral panics about Black masculinity and sexuality. Merian C. Cooper’s 1933 original, which draws heavily on the representational traditions of lost world adventure fiction, is widely considered to be an allegory of slavery and imperial exploitation, a tragic parable of man’s ruthless, irreverent, and self-involved abuse of the world’s majestic wildness. John Guillermin’s 1976 US version would more explicitly locate the story in the context of petropolitics, as the colonizing expedition to Skull Island is motivated not by a desire to capture a mythic beast but, more prosaically perhaps, to drill for oil. When Peter Jackson remade the movie in 2005, he made it a satire of the entertainment industry, casting Carl Denham as a roguish, self-destructive genius, an Orson Welles figure whose visionary talent threatens to destroy all of those near to him, and whose pledges to complete his work in the honor of the people who died in its course recalls the increasingly desperate dedications of documentarian-cum-unintentional-murderer Remy in 1992’s Man Bites Dog. For Jackson, Denham is like Kong, an unstoppable and doomed force of nature who destroys by loving.

Every Hollywood version of the original story, though, however sophisticated, simultaneously exploits the persistent racist panic about Black male desire for white women that is embedded into the fabric of the story. King Kong is, at its heart, a story about the violent death that inevitably looms at the horizon of Kong’s love for human women, a fable that has always been read as a racist allegory of the tragedy and illegitimacy of Black men’s supposedly insatiable appetite for the love of white women.

King Kong Vs. Godzilla is no exception here, as Kong’s storyline fuses critique of corporate colonialism with a problematic representation of Black desire. The characters’ extractivist plunder of Kong’s home island—changed from the enigmatic and unlocatable Skull Island to Pharaoh Island, a fictionalized landmass among the Solomon Islands—is the incident that prompts the confrontation between the two legendary beasts, and the Pacific Pharmaceutical execs who exploit Pharaoh Island for its pleasantly intoxicating fruit are shown as single-minded, hubristic buffoons as they capture Kong with the insane intent of using him to advertise their company. The clash of titans still makes time for a comedic critique of the ruthlessness of the capitalist advertising industry; so too does it retain Kong’s fascination with human women, as he scales a government building while clinging to a beautiful young woman he has captured.

The natives of Skull Island, too, are always a problem for these films. From Cooper’s original painted tribe of Kong-worshippers, to Jackson’s violent brutes (who recall the Uruk-Hai orcs from his Lord of the Rings trilogy), to the noble savages of 2017’s Kong: Skull Island (who recall Kurtz’s sinister and silent tribe in 1979’s Apocalypse Now), the human inhabitants of Kong’s home are routinely represented in extraordinarily dehumanizing ways.

Once again, King Kong Vs. Godzilla follows suit. The tribe of Faro Island is portrayed by actors in full-body blackface, and the Pacific Pharmaceutical employees bribe them with a transistor radio and tobacco. This patronizing bargain, in which they steal the island god in return for habit-forming poison and toys, is part of the film’s critique of exploitative capitalism; it is also, however, played for laughs. No matter how progressive the themes, a film that features dehumanizing ridicule like this is irredeemably racist. It is interesting, too, that the first major development in the Godzilla franchise’s relationship with its US audience foregrounds anti-Black racism, as though one of the safe territories on which the US and Japan could rebuild their relationship was the imperialist dehumanization of Black people.

For King Kong vs. Godzilla is historically and politically significant most of all because it was an international co-production between Japanese and American filmmakers. Where the original Godzilla is a fable of the nuclear suffering that the US inflicted upon Japan, made only two years after the conclusion of the post-war American occupation, King Kong vs. Godzilla is a symbol (and product) of the renewed Pacific alliance and the reestablishment of geopolitical cooperation between the US and Japan. Ishiro Honda returned to direct the original Japanese version for Toho, released in 1962, and John Beck helmed the adaptation of the US version for Universal Pictures, which was released the following year. This collaboration would fuel a monster movie franchise that endures today.

“This is UN reporter Eric Carter with the news”

Prior to Emmerich’s 1998 adaptation, every time a Godzilla movie appeared in Western markets it would be bowdlerized in some way. The movies were often retitled, recut, or given comically bad English dubbing; some of them, such as the original Godzilla and Godzilla 1985, were reshot, with American stars retroactively given focalizing roles in order, it was thought, to make the films more appealing to American and European audiences. Many of the recuts were extraordinarily unforgiving—the NBC screening of Godzilla vs. Megalon, for example, savagely streamlined the movie down to just 48 minutes, cutting out almost half of the movie in order to accommodate commercials and a Godzilla-suited John Belushi’s accompanying skits.

King Kong vs. Godzilla is unique in the way it is recut. A great deal of Honda’s original is brusquely shaven off and replaced, not with dramatic scenes featuring American actors, but with newscast-style footage of a reporter, Eric Carter, explaining the events of the plot directly to the audience. There is an amusing irony here: in the Japanese version, Pacific Pharmaceutical needs to use Kong for advertising because their own TV show is “dull, boring, and without imagination.” Carter’s broadcasts are almost as dry as the output of Pacific Pharmaceutical’s fictional TV network, as clumsily direct and awkwardly literal an expository device as you are ever likely to see in any film. Carter, the voice of the movie, is the antithesis of “show, don’t tell,” sometimes dictating not only the events but the way we should feel about them, too.

This clunkily oratorical exposition may be dramatically flat, but it has the virtue at least of being swift. One of the enduring problems of the Shōwa Godzilla series is the grinding slowness of some of the utterly turgid exposition, so it is in a way gratifying for an audience to be simply given the facts rather than having to yawn through interminable dialogue. And Carter’s scenes are also, sometimes, wonderfully comic. The scene in which he invites a paleontological expert into the studio to explain Godzilla’s origins and anatomy, for instance, features this expert—purportedly from New York University—using a child’s illustrated guide to dinosaurs as a visual aid.

And this formal oddness did nothing to stop the film’s popularity, as it was a hit on both sides of the Pacific. Strangely, though, given the film’s walloping success, Godzilla and Kong would never meet again until this year’s Godzilla vs. Kong, produced as part of Legendary’s MonsterVerse, which will be released almost a full sixty years after the movie it pays homage to. This seems odd, given that Toho retained the rights to Kong long enough to make King Kong Escapes in 1967, and that Toho was keen to make Godzilla face off against certain foes repeatedly—notably Mothra (four times), King Ghidorah (six times), and Mechagodzilla (five times).

The original was also uniquely difficult to acquire on home video for years, which meant that King Kong Vs. Godzilla became something of a myth, a legendary “lost” movie, particularly in my wet corner of Tory England. It was rarely if ever screened on British TV (not even in the small hours of the morning), and when a series of affordable VHS releases of Shōwa classics was released to coincide with Emmerich’s Hollywood Godzilla, King Kong Vs. Godzilla was nowhere to be seen among them, much to my adolescent disappointment. The US version was unavailable on DVD before 2006, and until the release of the 2019 Criterion Shōwa Blu-Ray box set, one of the only ways to get hold of the Japanese cut of the film was through obscure mail-order catalogs or DVD-R bootlegs.

Its iconic success, its lack of repetition, and its unavailability led to the attachment of a quasi-mythological status to this singular and mysterious film—a film that for many years of my pre-internet youth I couldn’t even confirm existed. Tantalizing half-truths and outright falsehoods circulated among fans like whispered playground rumors, further distorted in the retelling. The most enduring of these claimed that the two versions ended differently, with Kong winning in the US version but with Japanese audiences seeing Godzilla emerge victorious.

Perhaps inevitably, when I saw the film for the first time it was extraordinarily disappointing. The US cut is far less coherent than the Japanese, with characterization, comedy, and subtext stripped out; the Godzilla suit looks tired; and the Kong suit is almost unbearably goofy (despite what I said about special effects not being important, it still smarts to see them be quite so poor). But such is the unpleasable nature of fans: nothing, no matter how spectacular, could have lived up to the King Kong Vs. Godzilla in my head, nurtured by years of feverish daydreaming and speculation.

In the final analysis, what is perhaps most striking about this movie is that its legacy—the structuring principle of the Kaiju battle film—saturates every Godzilla film to come. The natives of Infant Island, home of Mothra, bear a striking resemblance to the natives of Faro Island, and the franchise as a whole is more than a little indebted to the problematic Kong mythos, not least in its representations of monster-infested lost world islands that seem to have avoided the great extinctions. This movie, and the trans-Pacific alliance of which it is so powerful a product, is in some ways the distilled essence of all the Shōwa Godzilla films: goofy, imperfect, but magically suggestive.

Alex Adams is a cultural critic and writer based in North East England. His most recent book, How to Justify Torture, was published by Repeater Books in 2019. He loves dogs.

Alex Adams is a cultural critic and writer based in North East England. His most recent book, How to Justify Torture, was published by Repeater Books in 2019. He loves dogs.

Another fairly notorious one. I can recall gamers in my Jr. High talking about how to stat up the sword from this. The start of this one is fun, love the wall of screaming faces.

Another fairly notorious one. I can recall gamers in my Jr. High talking about how to stat up the sword from this. The start of this one is fun, love the wall of screaming faces.