Let's start off the week with a game that is brand new. How new? It was only two months ago that I was interviewing the author and designer, Christopher Grey, for the Kickstarter.

Last week or so I go my physical copy in the mail and codes for my DriveThruRPG downloads. That was fast. So such a speedy response deserves a review.

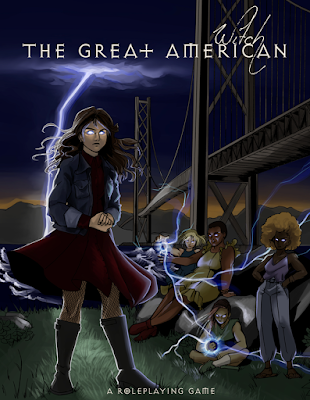

The Great American Witch

The Great American Witch

by Christopher Grey

For this review, I am considering the hardcover, letter-sized book, and the PDF. On DriveThruRPG you get two different layouts of the core book (1 and 2 page spreads), and several ancillary files for the covens and the crafts. I was a Kickstart backer and got my products via that. Both the hardcover and the pdfs are available at DriveThruRPG.

The Great American Witch is 162 pages, all full color, with full color covers. The art is by Minerva Fox and Tithi Luadthong. There are also some photos that I recognize from various stock art services, some I have even used myself. This is not a criticism of the book; the art, all the art, is used effectively and sets the tone and mood of the book well.

The rule system is a Based on the Apocalypse World Engine variant. Over the last couple of years I have had mixed, to mostly negative feelings about the Apocalypse World Engine. Nothing to do with the system itself, but mainly due to how many designers have been using it. I am happy to report that the version being used in TGAW is a stripped-down version that works better for me.

It is also published by Gallant Knight Games, who has a solid reputation. So out of the gate and barely cracking open the book it has a lot of things going for it.

The Great American Witch is a cooperative, story-telling game of witches fighting against perceived injustices in the world. I say "perceived" because of what injustices the witches fight against is going to largely depend on the witches (and the players) themselves. The framework of the game is built on Grey's earlier work, The Great American Novel. TGAW is expanded from the earlier game.

Like many modern games, TGAW has a Session 0, for everyone to come together and talk about what the game should be about, what the social interaction rules are, and what the characters are. The older I get the more of a fan of Session 0 I become. As a Game Master, I want to make sure everyone is invested in the game, I want to be sure everyone is going to have a good time. So yes. Session 0 all the way. The first few pages detail what should be part of your Session 0. It's actually pretty good material that can be adapted to other games.

The game also wears its politics on its sleeve. Frankly, I rather like this. It helps that I also happen to agree with the author and game here. But besides that, there is something else here. This game takes the idea, or even the realities and the mythologies of the witch persecutions and "Burning Times" and revisions them into the modern age. It is not a bridge to far to see how the forces of the Patriarchy and anti-women legislation, politics, and religion of the 16th to 17th centuries can be recreated in the 21st century. After all, isn't "The Handmaids Tale" one of the most popular and awarded television programs right now? There is obviously something to this.

The main narrative of the game comes from the players themselves. The Guide (GM) plays a lesser role here than in other games; often as one running the various injustices, NPCs, or other factions the players/characters/witches will run up against. The system actually makes it easy for all players to have a character and rotate the guide duties as needed.

True to its roots games are broken down into"Stories" and "Chapters" and who has the narrative control will depend on the type of chapter. A "Story" is a game start to finish. Be that a one-shot or several different chapters over a long period of time. A "Montage" chapter is controlled by the players. A "Menace" chapter is controlled by the Guide. A "Mundane" chapter is usually controlled by the player and the details of that chapter are for that character alone. "Meeting" chapters involve the characters all together and are controlled by them. "Mission" chapters are the main plot focus that move the story forward. "Milestones" are what they sound like. This is where the witch would "level up."

The game uses three d6s for the rare dice resolution. Most times players use a 2d6 and try to roll a 7 or better. "Weal" and "Woe" conditions can augment this roll. The author makes it clear that you should roll only when the outcome is in doubt. There are a lot of factors that can modify the rolls and the conflicts faced. It is assumed that most conflicts will NOT be dealt with with a simple roll of 7 or better. The author has made it clear in the book and elsewhere that more times than average a conflict is not just going to go away like defeating a monster in D&D. Conflicts are akin to running uphill, that can be accomplished, but they will take work and they will not be the only ones.

Once gameplay is covered we move into creating the player character witches. The book gives the player questions that should be answered or at least considered when creating a witch character. Character creation is a group effort, so the first thing you create is your group's Coven. This also helps in determining the type of game this will be as different covens have different agendas. There are nine different types of Covens; the Divine, Hearth, Inverted, Oracle, the Storm, Sleepers, the Town, the Veil, and Whispers. Each coven has different specialties and aspects. Also, each Coven has a worksheet to develop its own unique features, so one Coven of the Storm is not exactly the same as another Coven of the Storm from another city or even part of the city. These are not the Traditions of Mage, the Covenants of the WitchCraftRPG, or even the Traditions of my witch books. These are all very local and should be unique to themselves. Once the coven is chosen then other details can be added. This includes things like how much resources does the coven have? Where does it get its money from? Legal status and so on.

If Covens cover the group of witches, then each witch within the coven has their own Craft. These are built of of archetypes of the Great Goddess. They are Aje, the Hag (Calilleach), Hekate, Lilith, Mary (or Isis), Spider Grandmother, and Tara. These are the Seven Crafts and they are the "sanctioned" and most widespread crafts, but there are others. Each Craft, as you can imagine, gives certain bonuses and penalties to various aspects of the witch and her magic. Aje for example is not a good one if you want a high value in Mercy, but great if you want a high number in Severity and mixed on Wisdom. All crafts are also subdivided into Maiden, Mother, and Crone aspects of the witch's life.

Character creation is rather robust and by the end, you have a really good idea who your witch is and what they want.

The Game Master's, or Guide's, section covers how to run the game. Among other details, there is a section on threats. While there are a lot of potential threats the ones covered in the book are things like demons, vampires, other witches, the fey, the Illuminati, ghosts and other dead spirits, old gods and good old-fashioned mundane humans.

The end of the book covers the worksheets for the various Covens and Crafts. You use the appropriate Craft Sheets for a character.

The PDF version of the book makes printing these out very easy. It would be good for every player to have the same Coven sheet, or a photocopy of the completed one, and then a Craft sheet for their witch.

While the game could be played with as little two players, a larger group is better, especially if means a variety of crafts can be represented. Here the crafts can strengthen the coven, but also provide some inter-party conflict. Not in-fighting exactly, but differences on how to complete a Mission or deal with a threat. After all, no one wants to watch a movie where the Avengers all agree on a course of action from the start and the plans go as though up and there are no complications. That's not drama, that is a normal day at work. These witches get together to change the world or their corner of it, but sometimes, oftentimes, the plans go sideways. This game supports that type of play.

The Great American Witch works or fails based on the efforts of the players. While the role of the GM/Guide may be reduced, the role and responsibilities of the players are increased. It is also helpful to have players that are invested into their characters and have a bit of background knowledge on what they want their witch to be like. To this end the questions at the start of the book are helpful.

That right group is the key. With it this is a fantastic game and one that would provide an endless amount of stories to tell. I am very pleased I back this one.

Plays Well With Others, War of the Witch Queens and my Traveller Envy

I just can't leave well enough alone. I have to take a perfectly good game and then figure out things to do with it above and beyond and outside of it's intended purposes. SO from here on out any "shortcomings", I find are NOT of this game, but rather my obsessive desire to pound a square peg into a round hole.

Part 1: Plays Well With Others

The Great American Witch provides a fantastic framework to be not just a Session 0 to many of the games I already play, but also a means of providing more characterization to my characters of those games.

Whether my "base" game is WitchCraftRPG or Witch: Fated Souls, The Great American Witch could provide me with far more detail. In particular, the character creation questions from The Great American Witch and Witch: Fated Souls could be combined for a more robust description of the character.

Taking the example from WitchCraft, my character could be a Gifted Wicce. Even in the WitchCraft rules there is a TON of variety implicit and implied in the Wicce. Adding on a "layer" of TGAW gives my Wicce a lot more variety and helps focus their purpose. While reading TGAW I thought about my last big WitchCraft game "Vacation in Vancouver." Members of the supernatural community were going missing, the Cast had to go find out why. The game was heavy on adult themes (there was an underground sex trafficking ring that catered to the supernatural community) and required a LOT of participation and cooperation to by the player to make it work. It was intense. At one point my witch character was slapped in an S&M parlor and I swear I felt it! But this is also the same sort of game that could be played with TGAW. Granted, today I WAY tone down the adult elements, but that was the game everyone then agreed to play. The same rules in TGAW that allow for "safe play" also allow for this. The only difference is that those rules are spelled out ahead of time in TGAW.

Jumping back and forth between the systems, with the same characters and players, and a lot of agreement on what constitutes advancement across the systems would be a great experience.

I could see a situation where I could even add in some ideas from Basic Witches from Drowning Moon Studios.

Part 2: Traveller Envy

This plays well into my Traveller Envy, though this time these are all RPGs. Expanding on the ideas above I could take a character, let's say for argument sake my iconic witch Larina, and see how she manifests in each game. Each game giving me something different and a part of the whole.

Larina "Nix" Nichols

CJ Carrella's WitchCraft RPG: Gifted Wicce

Mage: The Ascension: Verbena

Mage: The Awakening: Path Acanthus, Order Mysterium

Witch: Fated Souls: Heks

NIGHT SHIFT: Witch

The Great American Witch: The Craft of Lilith OR The Craft of Isis.*

There is no "one to one" correspondence, nor would I wish there to be. In fact, some aspects of one Path/Order/Tradition/Fate/Craft will contradict another. "The Craft of Lilith" in GAW is a good analog to WitchCraft's "Twilight Order" and the "Lich" in Witchcraft: Fated Souls. But for my view of my character, this is how to best describe her.

* Here I am already trying to break the system by coming up with a "Craft of Astarte" which would be the intersection of Lilith and Isis. Don't try this one at home kids, I am what you call a professional.

Part 3: War of the Witch Queens

Every 13 years the witch queens gather at the Tredecim to discuss what will be done over the next thirteen years for all witches. Here they elect a new Witch High Queen.

One of the building blocks of my War of the Witch Queens is to take in as much detail as I can from all the games I can. This is going to be a magnum opus, a multiverse spanning campaign.

What then can the Great American Witch do for me here? That is easy. Using the coven creation rules I am planning to create the "coven" of the five main witch queen NPCs. While the coven creation rules are player-focused, these will be hidden from the players since the witches are all NPCs. They are based on existing characters, so I do have some external insight into what is going on with each one, but the choices will be mine alone really.

Looking at these witches and the covens in TGAW they fit the Coven of the Hearth the best.

Coven of the Hearth, also known as the Witches' Tea Circle (tea is very important to witches).

Five members, representing the most powerful witches in each of the worlds the Witch Queens operate in.

Oath: To work within witchcraft to provide widespread (multiverse!) protection for witches

Holy Day: Autumnal Equinox. Day of Atonement: Sumer Solstice. Which was their day of formal formation as well.

Hearth: A secured build in an Urban setting.

Sanctuary: Lots of great stuff here, and all of it fits well.

Connections & Resources: Organization charged with finding those in need.

Going to the Coven Worksheet:

Resources: Wealthy coven (they are Queens)

Makes money? A shop. Let's say that the "Home, Heart & Hearth" stores from my own Pumpkin Spice Witch book are the means to keep this operation funded.

Distribution: Distributed based on need.

Status: Mainstream. They ARE the mainstream.

Importance? Witches need to come together.

Mundanes? Mundanes are important. but not for the reasons listed. Mundanes are the greatest threat.

Influence: Extraordinary.

Members: Five or six local, but millions in the multiverse.

Authority: Through legacy and reputation

Wow. That worked great, to be honest.

Here's hoping for something really big to come from this.

Snowbeast

Snowbeast