Outsiders & Others

Feculent Fantasy

The primary drive behind the Old School Renaissance is not just a nostalgic drive to emulate the fantasy roleplaying game and style of your youth, but there is another drive—that of simplicity. That is, to play a stripped back set of rules which avoid the complexities and sensibilities of the contemporary hobby. Thus, there are any number of roleplaying games which do this, of which Ancient Odysseys: Treasure Awaits! An Introductory Roleplaying Game is an example. Ordure Fantasy, published by Gorgzu Games is an incredibly simple Old School Renaissance-style fantasy roleplaying game using a single six-sided die with a straightforward mechanic throughout, and providing four character Classes, offbeat monsters, and table upon table for generating elements of the world, from setting, quests, and locations to NPCs, dungeons, and random encounters.

The primary drive behind the Old School Renaissance is not just a nostalgic drive to emulate the fantasy roleplaying game and style of your youth, but there is another drive—that of simplicity. That is, to play a stripped back set of rules which avoid the complexities and sensibilities of the contemporary hobby. Thus, there are any number of roleplaying games which do this, of which Ancient Odysseys: Treasure Awaits! An Introductory Roleplaying Game is an example. Ordure Fantasy, published by Gorgzu Games is an incredibly simple Old School Renaissance-style fantasy roleplaying game using a single six-sided die with a straightforward mechanic throughout, and providing four character Classes, offbeat monsters, and table upon table for generating elements of the world, from setting, quests, and locations to NPCs, dungeons, and random encounters.Ordure Fantasy: A simple d6 roleplaying game starts with its mechanic. To undertake an action for his character, a player rolls a single six-sided die, aiming to get equal to or under the value of a Skill or Ability to succeed. Easy and Hard Tests are made with two six-sided dice, the lowest value kept for Easy Tests, the highest value retained for Hard Tests. For deadly, dangerous, cataclysmic or annoying situations, the Referee can demand that a player make an ‘Ordure Test’. On a result of a six, the ‘Ordure’ of the situation happens, on a result of four or five, the Player Character gets a rumbling, warning, or unsettling portent of the ‘Ordure’. If the ‘Ordure’ situation persists, the ‘Ordure’ range on the die expands from a six to five and six, then four, five, and six, and so on. Essentially, the ‘Ordure’ Test is a random response generator to dire situations, enforcing the fact that the world is a dangerous place, one in which the ‘heroes’ are not actually capable of dealing with based on their own abilities or skills—more random fortune. However, Ordure Fantasy does not suggest what such situations might be.

Combat is more complex in Ordure Fantasy. Initiative is handled by lowest rolls acting first, and attacks by a player rolling under his character’s Combat skill. If a Player Character is hit, then his player can roll a Body or Mind Test for his character to defend. All attacks inflict a single point of damage which is deducted from the Health of a Player Character or NPC. Enemies—whether a monster or an NPC, have only the Ability, that is, Health, and when Health, whether that of a Player Character, monster, or NPC, is reduced to zero, then they are dead. In addition, some Player Characters, NPCs, and monsters have abilities and skills that will inflict various effects in addition to the deduction of a single point of Health—and they can be quite nasty. Thus, the Nursing Acid Wing has a grasp attack and the Mercenary Class’ Sword Skill can be good enough to lop off the limbs and appendages of his enemies—if the rest of the Combat Test is good enough.

Ordure Fantasy provides a half-dozen monsters—not really enough, but very much not traditional fantasy in terms of their design, a page of notes and advice for the Referee, all decent enough, before it gets down to creating Player Characters. A Player Character is defined by three Abilities—Body, Mind, and Luck, plus his Health, Class, equipment, and money. There are four Classes—Mercenary, Conjurer, Scoundrel, and Curate, each of which maps onto the four Classes of classic fantasy roleplaying. The Mercenary is soldier of fortune, trained in the arts of war without loyalty to any lord or realm; the Conjurer an autodidact explorer of unreal realms and summoner of fey things; the Scoundrel a charming alley rat unconcerned with the law; and the Curate, the neophyte scion of some cult excommunicated for heretical and gnostic preachings. So, there is a sense that the characters of the world of Ordure Fantasy are ne’er-do-wells, brutes, uncaring, cynical bastards in a landscape of grim and dangerous peril.

Each Class has four Skills and a Boon. Skills can be used as often as necessary, whilst Boons can be used once per game session. For example, the Mercenary has Bow, which provides a ranged attack; Sword, a melee attack capable of taking off limbs; Shield, which improves a Mercenary’s defence for a melee turn; and Intimidate. The Mercenary’s Boon is ‘Execute’. Simply, the Mercenary declares a target and his next successful attack against them is instantly fatal. Ouch!

To create a Player Character in Ordure Fantasy, a player assigns a value of three to one Ability, two to another, and one to the third. All Player Characters have a Health of five. The player selects a Class and picks three of its Skills, and just like Abilities, assigns a value of three to one, two to another, and one to the third. It is a simple, fast process.

Evota the evasive

Scoundrel, Level 1

Body 1 Mind 2 Luck 3

Skills: Negotiate 1, Hide and Sneak 3, Lockpick 2

Boon: An Old Friend (Roll twice on each side of the Random Reaction table and select combination for the relationship).

Money: 30 sp.

Magic in Ordure Fantasy is both interesting and banal. The Curate simply gets Heal, Curse, and Resurrect as Skills, and these feel banal and flavourless. They ape the divine magical abilities found in other fantasy roleplaying games and they are simply not that interesting. In comparison, the Conjurer has interesting magic and really gets to do things with it. What a Conjurer can do is summon. This is modelled with the Summon Emotion, Summon Element, and Summon Being Skills. The first of these enables a Conjurer to flood a sentient being’s mind with an emotion of the Conjurer’s choice, the second to summon a fist-sized ball of an element the Conjurer has seen before, and the third a being the Conjurer has seen before—and the Conjurer can control numerous beings once he rises far enough in Levels. Simply, there is a flexibility to these Skills, a flexibility limited only by the player’s imagination and the Referee’s agreement. So there is potential for a lot of fun with the Conjurer Class, whereas the Curate not so much.

Experience again is simple in Ordure Fantasy. A Player Character who survives an interesting, dangerous, exciting, or entertaining session goes up a single Level. When he does, the Player Character is awarded a single point which his player can assign to an Ability or Skill to increase its value by one. The maximum value for any Ability or Skill is four, a Player Character can learn its fourth Skill at Third Level, and the maximum Level for any Player Character is six.

Equipment—especially enchanted and mythical equipment, is again simply handled. The former, for example, magical maps or a master thief’s tools, make Skill Tests easy, whilst the latter are so well crafted and infused with magic that they grant a +1 bonus to a particular Ability or Skill. Given the one to six scale of Ordure Fantasy, such mythical items are really powerful and may provide benefits beyond the simple bonus.

Over a third of Ordure Fantasy is devoted to ‘Referee’s Tables’. These start out with a table for what the Player Characters doing when the first session starts, and then goes on to define the danger in the particular realm, what adventurers are needed for or do, and what the town where the Player Characters are is, what quest is available there, what the dangerous region outside the town is, and so on. There are twelve tables here, each with multiple options, which with just a few rolls of a die, the Referee can generate a sheaf of hooks and elements around which she can base an encounter, a scenario, or even a mini-campaign, perhaps even as the game proceeds.

Physically, Ordure Fantasy is a nineteen page, 2.78 Mb, full colour PDF. The layout is clean and tidy, and it is illustrated with okay, if scratchy pen and ink drawings. The use of colour is minimal though and although attractive, does not add to the look of the game. It does need an edit in places. The last page in Ordure Fantasy is the character sheet, which clear and easy to use, and as a nice touch, includes the basics of rolling Tests and the Combat Rules for easy reference by the players.

If there is anything missing from Ordure Fantasy, it is a scenario. Certainly, the inclusion of such a sample adventure would have supported its ‘pick up and play’ quality, for Ordure Fantasy is really easy to learn and lends itself to quick and dirty games. Similarly, It would have been nice to have seen more monsters, though there is a table for generating foes, but it is kind of buried in the back of the game. The only other issue is the Curate Class, which is more useful to have someone playing it rather than actually being interesting to play.

Overall, Ordure Fantasy does what it sets out to do, and that is present a stripped down, fast-playing grim and gritty set of mechanics, that support its grim and gritty tone.

[Free RPG Day 2020] The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

The third offering from Renegade Game Studios is The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl, a quick-start for Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys. It presents a full scenario—with room for expansion and development by the Game Master, an explanation of the rules, and four pregenerated Player Characters, all designed to introduce both players and Game Master to the world of Overlight. This is a world of seven great continent, known as Shards, hanging in the sky under each other in a sky of limitless, unending light. These continents may shift horizontally, but never vertically, night only falling when one continent passes over another. Each continent is different, from the rocky towers and crumbling mesas across an expanse of blasted desert that is Nova, home to giant, sentient and meditative centipedes, called Novapendra, to Pyre, a landscape swathed in tundra and steppes, rarely lit beyond the fiery glow of its volcanos. They are home to numerous species, not just Humans or Haarkeen, but also Teryxians, the small, feathered reptilians of Quill, once emperors, but now renowned as academics and philosophers; the tribal, sometimes tree-like Banyan; and the eerily tall and thin, mask-wearing Aurumel of Veile, who aspire to build great things.

To a certain few, the brilliant, white light of the Overlight can split into a spectrum of different colours and Virtues—Compassion (green), Logic (blue), Might (red), Spirit (white), Vigor (orange), Wisdom (purple), and Will (yellow). So with ‘Root!’, a Banyan can encourage the vines and branches in his body to grow and grasp something—a person, an object, the ground—in a particularly tight grip or with ‘Speaker’s Fire’, an Embertongue can influence others in a soothing subtle fashion. The Overlight flows through and around everything, but those who can manipulate it are known as Skyborn and their powers of the Overlight as Chroma.

A character in Overlight and thus The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is defined by the seven Virtues—Compassion, Logic, Might, Spirit, Vigor, Wisdom, and Will. Most Virtues have Virtue has two or skills attached to it and both skills and Virtues are rated by die type. The exception is Spirit, which is just a pool of points for activating Chroma. Besides a name, a character will also be defined by his Folk—species and culture, core Virtue, a background, and wealth. To undertake an action, a character’s player rolls a Test, which depending upon the circumstances can be a Skill Test, an Open test, a Wealth Test, or a Chroma Test. For any Test, the player rolls seven dice, usually consisting of three dice equal to the character’s skill, three equal to his Virtue, plus the Spirit die, which is always four-sided die. For example, a Banyari faced by an angry animal which he wants to calm down, his player would roll three ten-sided ice for his Compassion Virtue, three six-sided dice for his Beastways skill, plus the Spirit die. Results of six or more count as a success and at least two successes are required to succeed at a Test, though without any flourish. A roll of four—or Spirit Flare—on the Spirit die can add a further success. The type of dice rolled varies depending upon the type of Test, but all are built around a pool of seven dice. For example, Chroma Tests, used to active Chroma abilities, typically use a combination of two Virtues plus the Spirit die—and it is the result on the Spirit die which determines how many Spirit points activating the Chroma costs. If it is too many and the character is low on Spirit points, the character suffers a Shatter as the raw divinity of the Overlight powers through him. This can lead to strange side effects and once a character has suffered his third Shatter for a Chroma, he is burnt out and cannot use that Chroma again. Overall, the rules in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl are succinctly described in just seven pages, including the skills list.

Four pre-generated characters are provided to play the scenario in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl. They include a Banyari Rootlord capable of using the Overlight to photosynthesise healing, grasp others with its vines and branches, or lash out in a fury of red fists and spectral fire; a Pyroi Embertongue capable of making friends and influencing others, and creating fire; a Haarken Grifter capable of hearing conversations at a distance; and a Teryxian Tutor capable of issuing uncompromising commands. Every character comes with three or pages of backgrounds and stats.

The scenario in The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is the eponymous ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’. This is a four-act mystery and missing persons adventure, which offers a mix of horror and exploration as well combat and interaction. It takes place on the on the forested Shard of Banyan where the Player Characters come across The Aquila, a ship-beast known as a Chrysoara, stricken with a sickness, its crew dead from acts of self-inflicted violence. This may simply at random, or they may be going to the rescue of the crashed ship-beast, or they may look for a missing scholar, Zubidiah Molok, who may or not be known to one of the Player Characters, and who even be mentor to one of them. From clues aboard The Aquila, the Player Characters will learn that scholar has made a great discovery deep in the forest. Following these clues will lead the Player Characters into dangerous territory and reveal some of the secrets of Overlight’s past.

As a scenario, ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’ is okay. It presents some of the setting to Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys and it provides a good mix of action and investigation, interaction and exploration, combat and horror. Each of the four Player Characters should certainly have a chance to shine. However, because the setting for Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys, and thus, ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’, is different, this scenario is not going to be one that flows. There will be plenty of stops and starts along the way as the Game Master has to explain—if not the rules, for they are quite straightforward, then aspect of the setting after setting. As a quick-start, The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl needs a cheat-sheet for it background more than it does for its mechanics. That said, from the information contained in its pages, the Game Master should be able to create one, just as she will be able to create the maps that would have been useful to frame and reference ‘The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl’. Of course, if she is doing that, then a handout or two would make the scenario a whole lot easier for both Game Master and her players.

Physically, The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is well presented. It is decently written, full colour, and comes with nice artwork. The lack of maps is an issue, but more of a problem is the fact that what is probably meant to be read aloud purple prose is not clearly marked as such and it feels like the author is repeating himself with every location description. This is frustrating experience for the Game Master trying to use the descriptions—both in the purple prose and the write-ups intended for her, because they look the same.

If a Game Master is already running an Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys campaign, then The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatll is likely easy enough to add to a campaign and it provides a decent enough scenario. For a group new to Overlight: The Roleplaying Game of Kaleidoscopic Journeys, then The Lost Spire of Tziuhuquatl is a decent introduction or a one-shot, although it needs a bit more work and a bit more of an explanation than it really should.

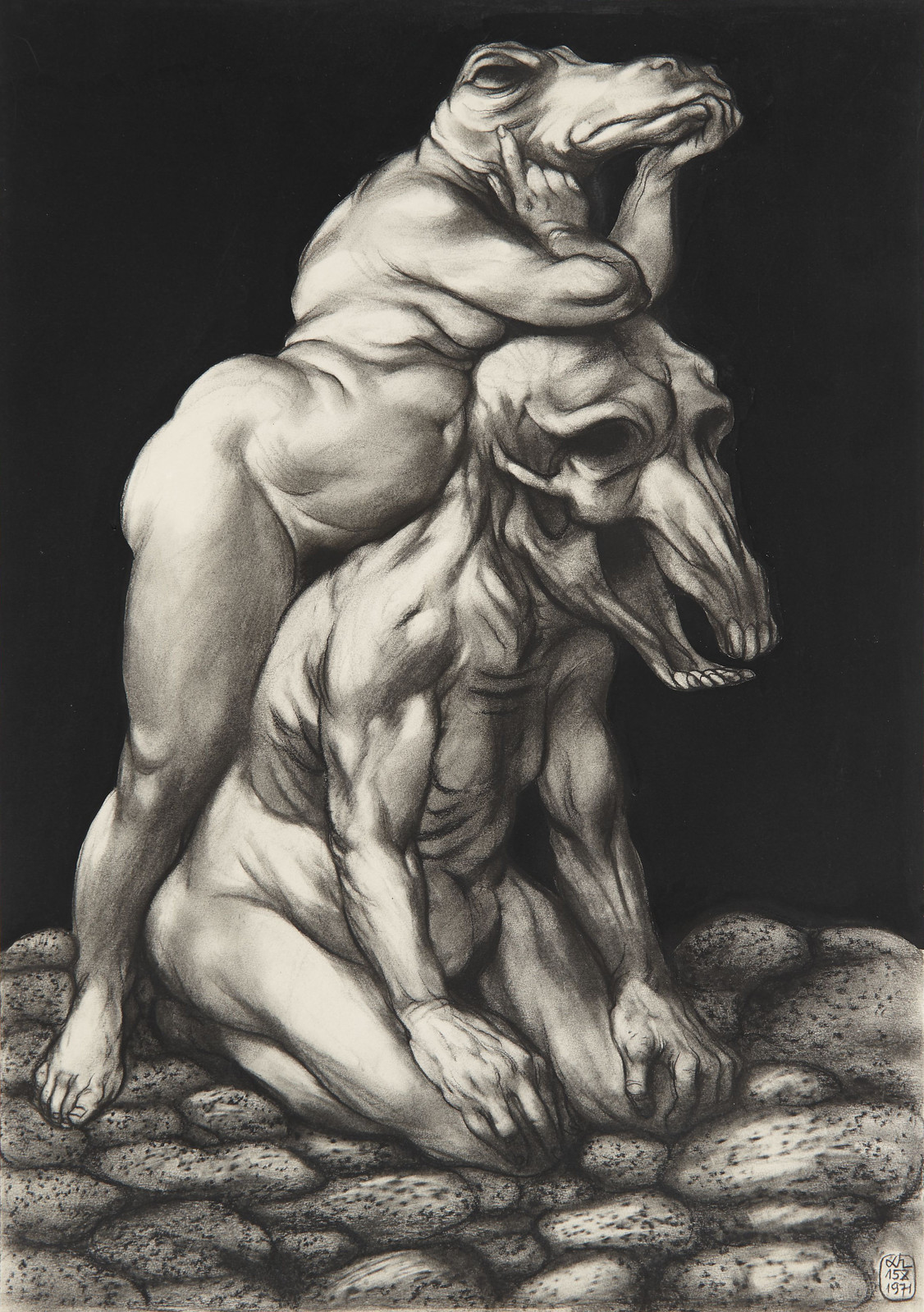

Richard Taylor (1902 - 70) - The Document

"Although Taylor is most known for his gag cartoons which poked fun at society, and humorous illustrations for a variety of books (Fractured French, My Husband Keeps Telling Me To Go To Hell, Half a Dollar Is Better Than None etc), it seems his private passion–and one he would pursue til late in life without seeking commercial benefit–was fantasy art. Taylor created a fantasy world called Frodokom, in which he based an entire series of watercolor, print and oil paintings that featured surrealistic creatures and landscapes. Maurice Horn’s Encyclopedia of Cartooning says of Taylor’s work “There is an individuality to his large-eyed, heavy lidded characters that makes one think of fairy tales and other worlds…” In the mid 1930s, he created 40 illustrations for Worm’s End, an adult fantasy book by Lionel Reed." - quote source.

Artwork found at Heritage Auctions.

A selection of Arkham House book covers by Taylor were previously shared here.

State of the Gallery: September 2020

Sunday Morning Porch Sale: September 20, 2020. Life’s No Fun Without A Good Scare.

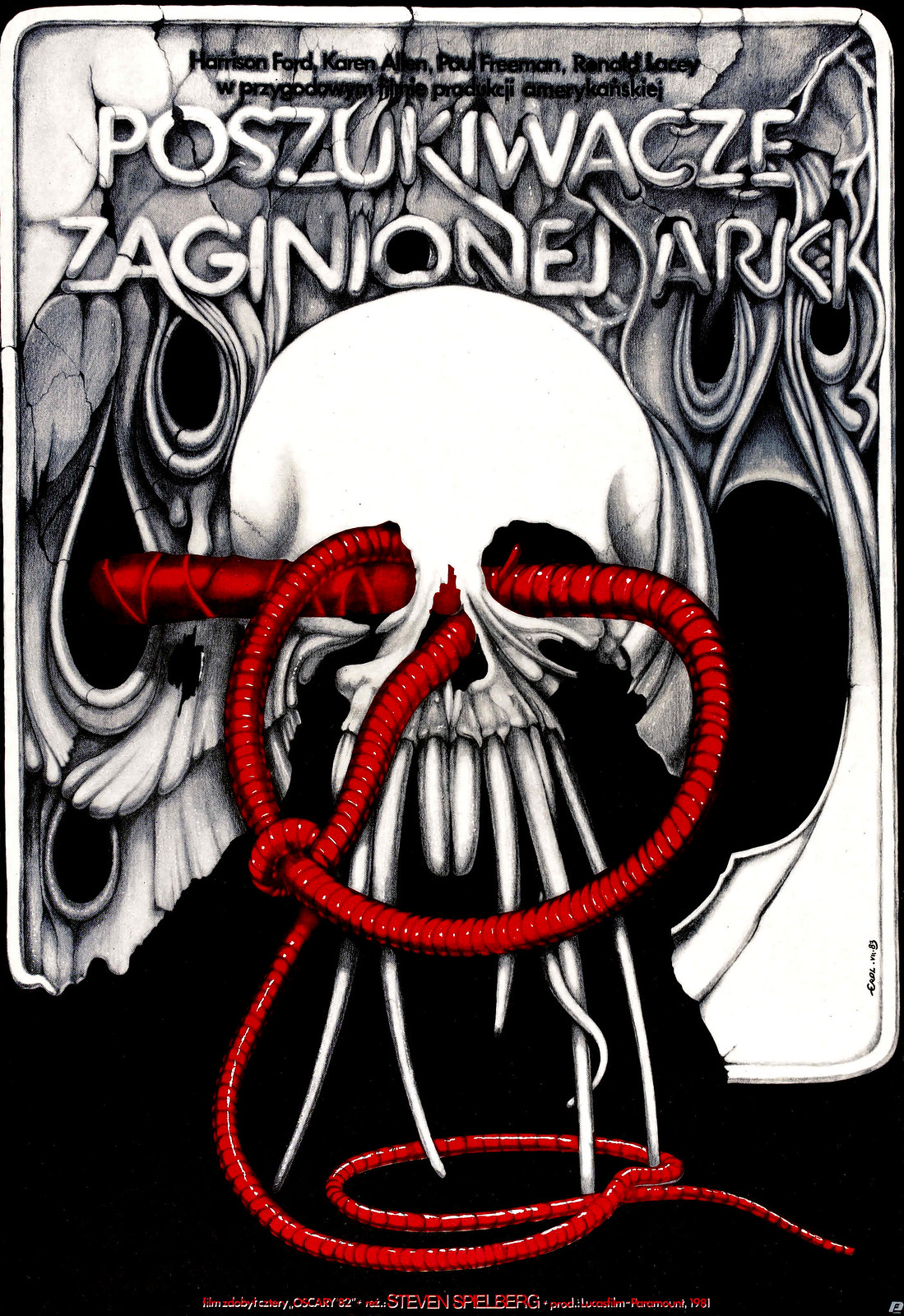

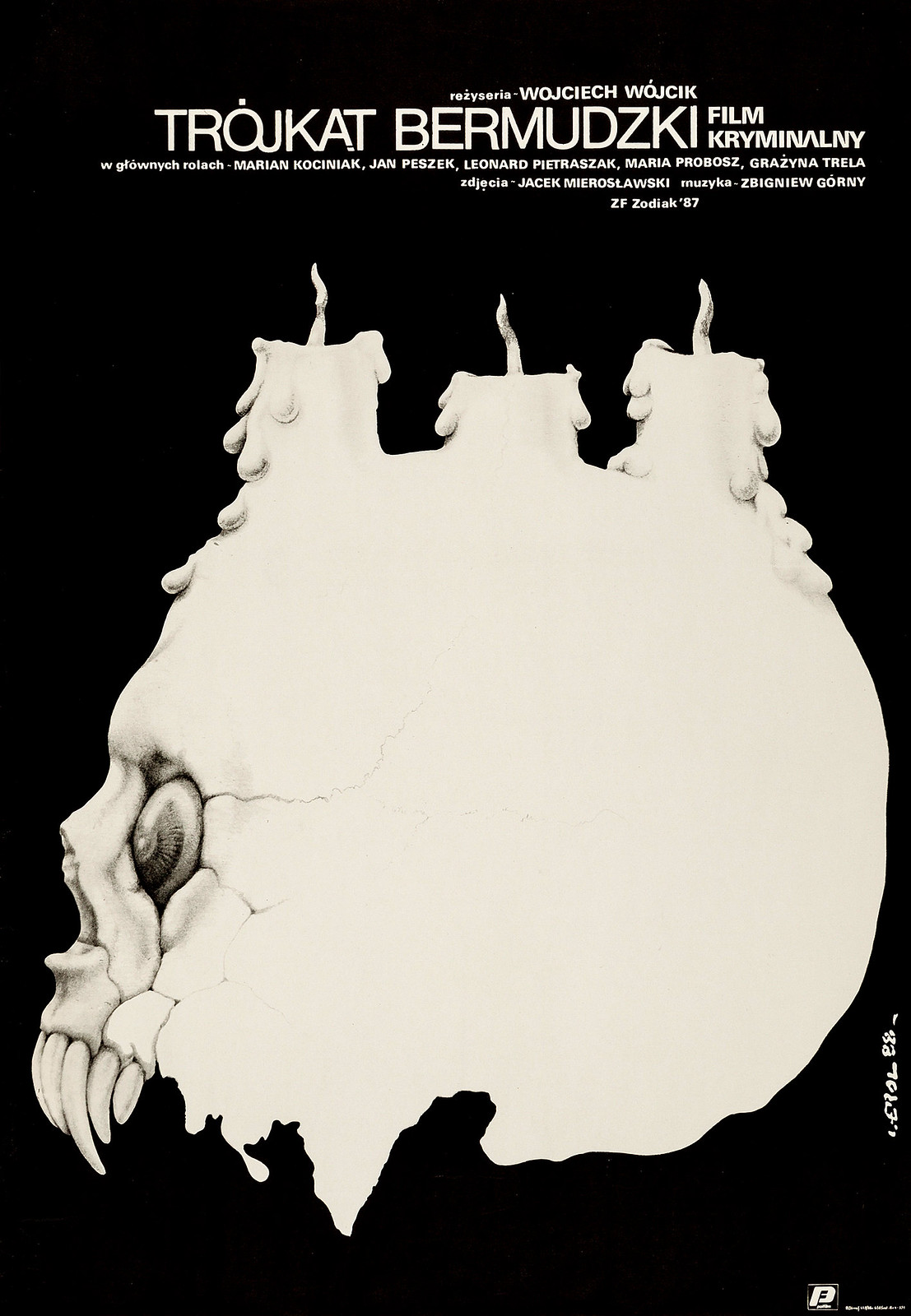

Jakub Erol (1941 - 2018) Polish Film Posters

Excited, Thrilled, Golly-Gee-Whizzed, and Titterpated too!

Been a while since I made a good Battletech post. I just finished Mr. Pardoe's recent novella "Divided We Fall". It's a great BT yarn, exciting, fast moving, engaging, and a real page turner. Also it has a special charm for me, as, in it, I am one of the fans Mr. Pardoe honors with an official alter ego in the Battletech Universe.

I've loved the game since it was first shown to me in 1987... Ah, High School, a terrible time in many respects, but my first friends were made over games of Battletech, and the universe has had my, sometimes near obsessive, attention ever since. Lord knows how much mayhem my imaginary other world self has caused, though I take pride in knowing I've always done all I could to minimize casualties, avoid the Civvies, and uphold the Aries Conventions...

I couldn't be more jazzed that a Character with my name is now a Cannonical part of the Universe; Brianne Elizabeth Lyons (Battletech Me) is a Colonel in Wolf's Dragoons! the best of the best! assigned to Logistics, which is exciting to me because I love thinking about Battletech logistics and strategic problems, and always imagined myself in that universe doing Operational Planning more than tactical field work. And, to boot, the Character pilots one of my favorite of all Battlemechs; the Urbanmech. I couldn't have asked for a more delightful and perfect representation, and it was all unasked, making it all the sweeter! Thank you Mr. P! You made one of my dreams a reality!

Anyhow, in the real world I've never quite felt comfortable with other super fans of the franchise, being a transwoman kinda has it's complications, even if they are usually inner ones, and I've shunned the community for the most part. It certainly doesn't help that the one tournament I entered; Amigocon '89, was ruined for me when I had to abandon the game because my Dad showed up and made me leave as we entered the final heat. I am sure I would have placed, but the cost to my familial relationships would have been severe... You know when you are really "in the zone" on something? you can see a few moves ahead, you know exactly what to do, and how to do it, and you can feel the victory in your fist? yeah, it's a rare exhilaration, I've felt it a few times, some hard fought chess games, and a couple of really busy Battletech games... And that day I totally had it. my Lance of Mediums; my Griffin, my pals playing an Assassin, a Centurion, and a Hunchback, we'd bested Warhammers, Riflemen, Marauders, and were still in good shape, fighting on a neat underground terrain board, using first rate tactics; scooting and shooting with care... it was a good free for all, and I would give my eyeteeth to see how it would have ended if I'd been allowed to stay and finish. it's my third greatest regret in my life. Well, that's all ancient history and water under the bridge as they say.

Times have changed since the late 80s... in the real world and in the game world. The Dragoons have a new logo...classic mech designs are re-imagined, and the clans have come, changing everything, everything except the one eternal truth; there will always be war so long as humanity remains...human.

Plans for October 2020

Adam Hoffmann (1918 - 2001)

Miskatonic Monday #52: Down New England Town

Between October 2003 and October 2013, Chaosium, Inc. published a series of books for Call of Cthulhu under the Miskatonic University Library Association brand. Whether a sourcebook, scenario, anthology, or campaign, each was a showcase for their authors—amateur rather than professional, but fans of Call of Cthulhu nonetheless—to put forward their ideas and share with others. The programme was notable for having launched the writing careers of several authors, but for every Cthulhu Invictus, The Pastores, Primal State, Ripples from Carcosa, and Halloween Horror, there was a Five Go Mad in Egypt, Return of the Ripper, Rise of the Dead, Rise of the Dead II: The Raid, and more...

The Miskatonic University Library Association brand is no more, alas, but what we have in its stead is the Miskatonic Repository, based on the same format as the DM’s Guild for Dungeons & Dragons. It is thus, “...a new way for creators to publish and distribute their own original Call of Cthulhu content including scenarios, settings, spells and more…” To support the endeavours of their creators, Chaosium has provided templates and art packs, both free to use, so that the resulting releases can look and feel as professional as possible. To support the efforts of these contributors, Miskatonic Monday is an occasional series of reviews which will in turn examine an item drawn from the depths of the Miskatonic Repository.

—oOo—

Name: Down New England Town

Name: Down New England TownPublisher: Chaosium, Inc.

Author: Michael LaBossiere

Setting: Small town, modern New England

Product: Scenario

What You Get: Ten page, 3.15 MB Full Colour PDF

Elevator Pitch: Hometown Horror Maestro Horror

Plot Hook: Sheriff stumped by removed remains of the recently deceased director of horror movies. Could his death have become a horror movie?

Plot Support: Five NPCs, new Mythos creature variant, and a map.Production Values: Tidy layout and decent illustrations.

Pros

# Potential hometown sidequest

# Simple story, one session scenario

# Good mix of NPCs for the Keeper to roleplay

# Potential convention scenario

# Easy to adapt to other time periods

# Roleplaying focused investigation

# Scope to play up the horror movie aspects

Cons

# Simple story, one session scenario

# Uninspiring new Mythos monster variant

# Underwritten investigation# one note, combat climax

Conclusion

# Solid addition to any ghoul campaign

# Scope to play up the horror movie aspects

# Roleplaying investigation needs development

Tour de Tabletop

A minor side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has delayed this review, because it has also delayed the reason for this review. The 2020 Tour de France was due to have started on June 27th and finish three weeks later on July 19th, but its starting date was delayed until 29th August and it is due to finish today, 20th September. Consequently, this review—of a cycling-themed game—is equally as late. Published by Lautapelit.fi, Flamme Rouge is a cycling racing game designed for two to four players, aged eight and above, which can be played in between thirty and forty-five minutes. The mechanics involve racing on a modular board, the hand management of dual decks, and simultaneous action selection, supporting play that is both simple and tactical, and ultimately, providing a game that really feels like a stage of one the Grand Tours—the Giro d'Italia, Tour de France, and Vuelta a España. Plus, there is nothing to stop a playing group to play Flamme Rouge more than once to simulate a Grand Tour!

A minor side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has delayed this review, because it has also delayed the reason for this review. The 2020 Tour de France was due to have started on June 27th and finish three weeks later on July 19th, but its starting date was delayed until 29th August and it is due to finish today, 20th September. Consequently, this review—of a cycling-themed game—is equally as late. Published by Lautapelit.fi, Flamme Rouge is a cycling racing game designed for two to four players, aged eight and above, which can be played in between thirty and forty-five minutes. The mechanics involve racing on a modular board, the hand management of dual decks, and simultaneous action selection, supporting play that is both simple and tactical, and ultimately, providing a game that really feels like a stage of one the Grand Tours—the Giro d'Italia, Tour de France, and Vuelta a España. Plus, there is nothing to stop a playing group to play Flamme Rouge more than once to simulate a Grand Tour!In Flamme Rouge, each player controls a team of two riders. One is the Rouleur, a good all-rounder, capable of maintaining a good pace throughout a race, the other is the Sprinteur, capable of bursts of great—typically as they are racing for the finishing line. Throughout the game, each player will control the speed of both his Rouleur and his Sprinteur, each of whom has a sperate movement deck. In general, he will keep his cyclists in the pack—or peloton—to conserve energy and speed, protecting the Sprinteur until close to the end when he can launch a sprint attack or he might launch a breakaway from the peloton and get to the finishing line before anyone else. However, this will exhaust a cyclist and probably enable the peleton to catch up. All cyclists though can take advantage of the slipstream effect to catch up and keep up with the cyclists in front of them. Since every team is trying to do this, the cyclists will be jockeying for position throughout the game.

Open up the box and you will find twenty-one double-sided Track Tiles consisting of Start and Finish sections, plus various straight and corner sections. All of the Track Tiles have two lanes and on the reverse are marked with Ascent and Descent sections which indicate mountain sections. There are eight custom plastic Cyclists—one Rouleur and one Sprinteur per player, marked with an ‘R’ and an ‘S’ respectively, and four Player Boards, one per player. Each board has spaces for the two decks of cards a player will draw from throughout the game. The game’s almost two hundred cards are divided into ten decks. Four of these are Energy decks for both the Rouleur and the Sprinteur, whilst the other two are Exhaustion decks, again one for Rouleurs and one for Sprinteurs. Each player has two Energy decks, one for his Rouleur and one for his Sprinteur. The two Exhaustion decks are drawn from by all of the players. Both Rouleur and Sprinteur Energy decks consist of numbered cards—each indicating the number of spaces a Rouleur or Sprinteur can move, the Rouleur’s between three and seven, and the Sprinteur’s between two and five, plus several nines. The value of the Exhaustion cards are all equal to two. Lastly, there are four Reference cards and six Stage cards. Each of the latter gives a layout for the Track Tiles to model a Stage from one of the Grand Tours. Lastly, the large, four-page rulebook explains how to set up and play Flame Rouge.

All of these components are of an excellent quality. Both the cards and Track Tiles have a linen finish and the Track Tiles are of thick cardboard. The rulebook is short and easy to read, and includes samples of play where necessary. Lastly, the plastic cyclists are not quite as nice as the other components, but both the Rouleur and the Sprinteur have different poses and the back of their jerseys are marked with an ‘R’ or an ‘S’ respectively for easy identification. The look of the game, of French cycling the 1930s, is really attractive and gives the game a classic feel.

Game set-up is simple. Each player receives a Rouleur and Sprinteur, Rouleur deck and Sprinteur deck, and player board, all in the same colour. The Track Tiles are laid out according to one of the Stage cards or a Stage of the players’ own design, and both Exhaustion decks are put beside the Stage layout. Then each player places his Rouleur and Sprinteur at the start of the Stage layout, the order determined by age and the last time the players each rode a bicycle.

Each round of Flamme Rouge consists of three phases—the Energy, Movement, and End phases. In the Energy phase, each player draws four cards from either his Sprinteur or Rouleur Energy deck, selects one to play, and returns the other three to the bottom of the appropriate deck. Then he does it to the other deck so that he one card from both of the Sprinteur and Rouleur Energy decks ready to play in the Movement phase. This can be done in any order, but once a card has been selected, a player cannot go back and change it.

In the Movement phase, the players reveal their cards and begin moving their cyclists, starting with the one at the front and working backwards in order. Each cyclist is moved forward a number of spaces as indicated on the respective Energy cards. A cyclist can be moved past another cyclist, but cannot land on a space occupied by one. Instead, the cyclist moves in behind the other. This will typically forces a player to be conservative in the choice of Energy cards he plays in order to prevent his wasting them in attempts to get his cyclists to pass those ahead of him, and whilst the players with cyclists at the front have a wider choice in the cards they play, they not do want necessarily to separate their cyclists from the ones behind them lest they begin to gain Exhaustion cards.

The End phase, all played Energy cards—for both Sprinteur and Rouleur—are discarded, and Slipstreaming and Exhaustion occur. If a cyclist ends his movement with exactly one empty space between him and the cyclist in front of him, then the cyclist can move exactly one space forward and close the gap. If there is more than one space between cyclists, then they are considered to be separate groups. It is also perfectly possible and legal to slipstream multiple groups, the slightly strung out cyclists taking advantage of the slipstream effect to come back together form a larger pack.

However, if there is still a gap of more than one space between any cyclists after those able to take advantage of the Slipstream effect, then those cyclists earn an Exhaustion card each. This is added to their respective Energy decks and when drawn and played, only enable a cyclist to move two spaces. What this means is that it pays for a cyclist to be conservative in his use of Energy. In the peleton, he can maintain the same speed as his fellow cyclists and gain advantage of the Slipstream effect if a rival cyclist decides to speed up. There is nothing to stop a cyclist making a break from the peleton, and just like in an actual Grand Tour, racing off into the distance, his player using the high value Energy cards in a cyclist’s deck to gain an advantage over his fellow cyclists. Just like a Grand Tower though, this will tire the cyclist out fairly quickly, modelled by the breakaway cyclist picking up more and more Exhaustion cards over the course of several turns. These will come to clog up a cyclist’s Energy deck, even as his player uses the higher value Energy cards up and discards them, ultimately slowing a cyclist down.

In the base set-up, a game will typically see the cyclists jockeying for position right down to the finishing line when Sprinteurs make a break for it in an attempt to win the stage. In the advanced game—which really only adds one or two rules, mountains can be added to Stages. Mountain sections on the tiles are marked into two colours—orange for ascent and blue for descent. When a cyclist is in an ascent section, and therefore travelling fairly slowly, the maximum value of any Energy card played is always five. If a higher value card is played, the number of spaces of movement it grants is reduced to five. Conversely, on the descent sections, when the cyclist is travelling really quickly, the minimal value of any Energy card played is five. What this means is that lower value Energy cards can be played and the cyclist gets the benefit of the increased value and because the card is also discarded from the game, it means that the player is not forced to use it later when it will not help his cyclists. This includes Exhaustion cards, and this is one way in which to remove them from a cyclist’s Energy deck.

Effectively, Flamme Rouge is a finely balanced energy management game, with players needing to keep their cyclists up with those of the other players and either not let their rivals get to far ahead—or at least keep up with them when they are! A player can also keep track of what Energy cards his rivals have played, but it is still possible to be outfoxed by a rival especially when mountains come into play and break up the cyclists into smaller groups. The mountains are all but a necessity as without them, Flamme Rouge is well, a bit flat, and just as the mountains break up the terrain, they provide an opportunity for the players to break up the bigger groups and form breakaways.

Flamme Rouge looks good and is both easy to learn, play, and teach. Above all, Flamme Rouge plays and feels like a stage of a Grand Tour, and there is a great ebb and flow to it—just like the real thing. For gamers who are also fans of cycling, Flamme Rouge is a game they are going to appreciate, whilst being accessible by gamers who are not cycling fans and cycling fans who are not gamers.

Magic, Murder, & Mystery

Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road is not a wholly new book for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. This is because it combines one of the first scenarios published for the then new version of the venerable Lovecraftian investigative horror with a wholly new scenario and several scenario seeds. The ‘old’ scenario is ‘Dead Light’, published in 2014 as Dead Light: Surviving One Night Outside Of Arkham, which in this new anthology published by Chaosium, Inc. has been joined by the new scenario, ‘Saturnine Chalice’. What connects the two—or at least what they have in common—is that they take place whilst the investigators on the road, and either because of the weather or because they get lost, the investigators will be confronted with mystery, magic, and mortality. Both scenarios are set in the 1920s, are quite nasty, both are self-contained, and both are nominally set in Lovecraft Country. What this means is that either can be slotted into an ongoing campaign whilst the investigators are travelling between locations or run as oneshots, and be moved to any remote location—all with relative ease. With a little effort, they could also be shifted to time periods other than the Jazz Age of the 1920s. Other than that, each scenario is very different in terms of structure, tone, and story, and so will provide very different roleplaying experiences.

Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road is not a wholly new book for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. This is because it combines one of the first scenarios published for the then new version of the venerable Lovecraftian investigative horror with a wholly new scenario and several scenario seeds. The ‘old’ scenario is ‘Dead Light’, published in 2014 as Dead Light: Surviving One Night Outside Of Arkham, which in this new anthology published by Chaosium, Inc. has been joined by the new scenario, ‘Saturnine Chalice’. What connects the two—or at least what they have in common—is that they take place whilst the investigators on the road, and either because of the weather or because they get lost, the investigators will be confronted with mystery, magic, and mortality. Both scenarios are set in the 1920s, are quite nasty, both are self-contained, and both are nominally set in Lovecraft Country. What this means is that either can be slotted into an ongoing campaign whilst the investigators are travelling between locations or run as oneshots, and be moved to any remote location—all with relative ease. With a little effort, they could also be shifted to time periods other than the Jazz Age of the 1920s. Other than that, each scenario is very different in terms of structure, tone, and story, and so will provide very different roleplaying experiences.‘Dead Light’ opens with the investigators on the road out of Arkham, heading for the town Ipswich. The weather has drawn and as the road is lashed by a fierce storm, the investigators are forced to slow—which proves to be fortunate when a disheveled and bewildered girl runs into the road. Thankfully, the investigators can take refuge with other travellers at the roadside Orchard Run Gas and Diner. Here they can also learn who the girl is and where she came from, but that begs the question of what forced her to flee into the night when the weather is as bad as this? Another question is what caused a local farmer to swerve his truck so leaving the road all but blocked and left him incoherent with shock? Is it because he is just drunk or are his claims of a bright light that caused him to swerve on the road true?

Further checking on the girl reveals more of the mystery and something of the threat that the investigators will face in and about the Orchard Run Gas and Diner. The threat almost has a Science Fiction feel to it and that is perfectly in keeping with the nature of Cosmic horror. Although its origins are never quite revealed, the purpose to which it has been put can be discerned, and it is horribly rational and thoroughly in keeping with the wider miscegenation found in Lovecraft Country.

‘Dead Light’ is both a tale of jealousy and greed, and a survival horror scenario. As a survival horror scenario, it is light both in terms of the traditional Mythos and detailed investigation. As a tale of jealousy and greed, there are plenty of opportunities for roleplaying though as the consequences of both come to roost in and around the Orchard Run Gas and Diner. The likelihood is that the scenario is much physical in nature as the investigators and the NPCs are stalked in the woods surrounding the roadside stop. Yet as physical as the scenario is likely to become, any investigator attempting to confront the threat with brute force is likely to end up sorely disappointed and quite possibly dead. What this means is that the investigators will need to look for the means to stop the threat—and doing so will reveal the origins of the threat and perhaps the human folly that led to its release.

The issue with survival horror and with a threat as deadly as that in Dead Light is that it is too easy to kill the investigators. Whilst the thing is hunting them and everyone at the café, the Keeper needs to pace the scenario and not have it hunt down and kill everyone. This does not mean that she should be lenient should a player have his investigator act foolishly, but with plenty of NPCs around to show how the monster works, the Keeper should sacrifice them and so hint at the thing’s lethality and give time for the investigators to uncover what is really going on. The danger here is that in the hands of an inexperienced Keeper, ‘Dead Light’ has the potential to result in the death of everyone at the Orchard Run Gas and Diner—including the investigators. A more experienced Keeper will know to play and draw the events of the scenario and the deaths of everyone present out over the course of the evening. Pleasingly, ‘Dead Light’ gives the Keeper the means and advice to that end. Essentially, the second or revised edition of the original scenario, minor tweaks and edits having been made here and there, ‘Dead Light’ is a still as good a scenario as it was in 2014.

‘Saturnine Chalice’ is a radically different scenario in comparison to ‘Dead Light’. It is very much smoke and mirrors, a drawing room mystery bordering on farce, all contained within a puzzle box. The scenario opens again with the investigators on the road and then, whether they have got lost or their vehicle has run out of petrol, needing to go for help. They find themselves at the home of Augustus Weyland and his daughter, Veronica, their hosts welcoming, offering to help them with their plight, and even inviting them to dinner. Surprisingly, both father and daughter are willing to not only entertain the existence of the occult, but openly discuss it, which seems all the stranger given that the investigators have not come looking for it—at least not at the Weyland house. As they interact with the hosts and servants, things get odder and there seems to be gaps in what each knows, culminating in what is a truly bizarre dinner—a scene which the Keeper should really relish portraying.

This and other clues should indicate that there is something strange going on in the house, which should ideally drive the investigators to search the house further—and if they refrain, then other events certainly will. What the investigators find is a clue-rich environment pointing to the events which lead up to the current situation, what is going on when the investigators enter the house, and how they can escape their predicament. Two methods are suggested in ‘Saturnine Chalice’ for handling these clues. One is to rely for the investigators’ skills and abilities, but the other is for the players themselves to take the clues and work out themselves aspects of the puzzle their investigators find themselves in. Certainly, the latter option adds a degree of physicality not normally present in Call of Cthulhu investigations. However, this may complicate play for some players and potentially increase the playing length of the scenario’s single session. Here the Keeper needs to take into account her players’ playing preferences—or at least be aware of their being expressed if ‘Saturnine Chalice’ is run for relatively inexperienced or new players.

In comparison to ‘Dead Light’, ‘Saturnine Chalice’ is far more of cerebral affair, though there are still moments of action. Both possess a fair degree of back story as well as potential hooks which could be developed by the Keeper—especially if either is run as part of a Lovecraft Country campaign. Even if the links are not developed, both are easy to slot into a campaign, or simply run as oneshots.

Rounding out Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road is a half dozen scenario seeds. In keeping with the theme of the book, these all start on the road. They take the investigators to a roadside cabin camp where the fellow guests are up to something in the nearby woods, past a strange, giant animal attraction which could be something more, to a suitcase left in the middle of the road, and then on past the same signpost—again, to be diverted into a deadly game of cat and mouse in a scrapyard, and at last, to a chance to be charitable and pick up a pair of innocent looking hitchhikers. In some cases, the scenario sees include one or more explanations as to what is going on, and a couple do include some interesting historical background. That said, some of them are perhaps a bit mundane. All though require some effort upon the part of the Keeper to develop into a full scenario.

Physically, Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road is nicely presented. It is well written, cleanly laid out, and the artwork, cartography, and handouts are all decent. The only thing which could be held against the book is that it is in black and white in comparison to the publisher’s other for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, but to be fair, this does not detract from the production values and this is still a good looking book.

Even with just the two scenarios, Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road is a nicely versatile anthology. Both scenario are very different in terms of their structure, tone, and play style, but both are easy to use. Whether the Keeper is looking to taunt her investigators with a night’s survival horror or a puzzle to unlock, Dead Light and other Dark Turns: Two Unsettling Encounters on the Road delivers both for Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition, along with a few extras.

Have a Safe Weekend

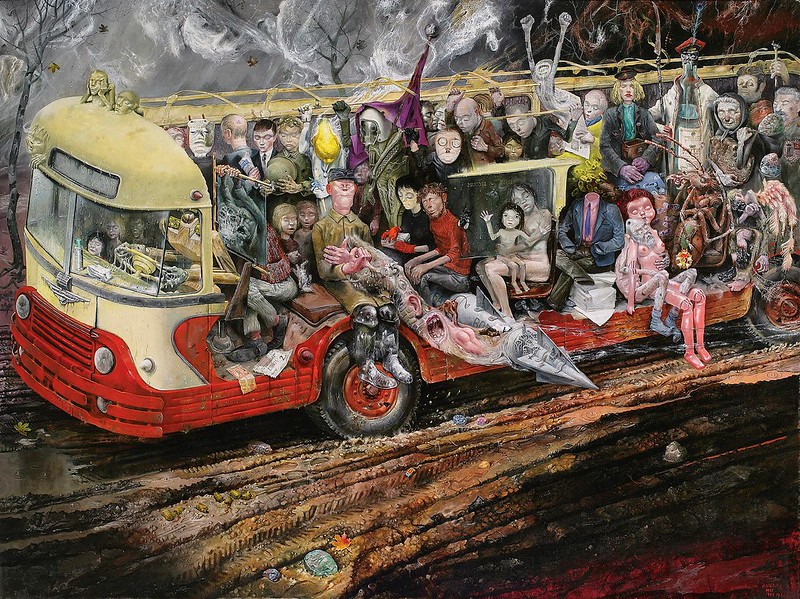

Bronisław Wojciech Linke (1906 - 1962)

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

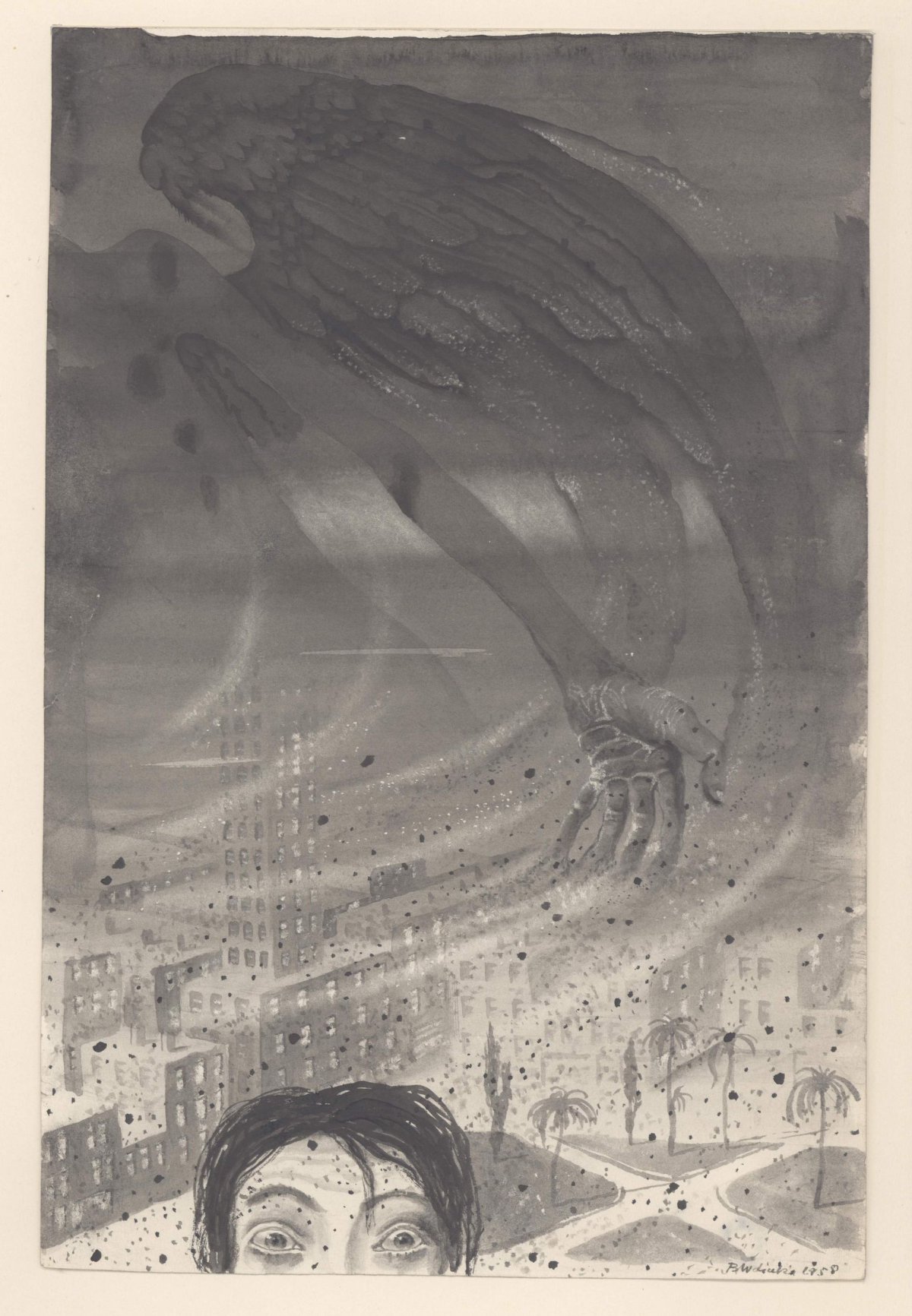

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

A biography on the artist's life can be found here.

[Free RPG Day 2020] Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.The contribution to Free RPG Day 2020 from Fantasy Flight Games is Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas. This is a quick-start for use with Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible, the roleplaying game based on the setting for Richard Garfield’s KeyForge: Call of the Archons, the world’s first Unique Deck Game. It uses the Genesys Narrative Dice System—first seen in Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, Third Edition—but ultimately derived from the original Doom and Descent board games. Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas comes with everything necessary to play—an explanation of the rules, four pregenerated characters, and an exciting, action-packed scenario for the Game Master to run. What it does not come with is dice and the fact that both the Genesys Narrative Dice System and Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible—and therefore Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas—use propriety dice is a problem. Not an insurmountable one, but a problem, nonetheless.

Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas opens with a rules summary. The core mechanic requires a player to roll a pool of dice to generate successes and should the roll generate enough successes, his character succeeds in the action being attempted. The complexity comes in the number of dice types and the number of symbols that the players need to keep track of. On the plus side, a player will be rolling Ability dice to represent his character’s innate ability and characteristics, Proficiency dice to represent his skill, and Boost dice to represent situational advantages such as time, assistance, and equipment. On the negative side, a player will be rolling Difficulty dice to represent the complexity of the task being undertaken, Challenge dice if it is a particularly difficult task, and Setback dice to represent hindrances such as poor lighting, difficult terrain, and lack of resources. Ability and Difficulty dice are eight-sided, Proficiency and Challenge dice are twelve-sided, and Boost and Setback dice are six-sided.

When rolling, a player wants to generate certain symbols, whilst generating as few as possible of certain others. Success symbols will go towards completing or carrying out the task involved, Advantage symbols grant a positive side effect, and Triumph symbols not only add Successes to the outcome, but indicate a spectacularly positive outcome or result. Failure symbols indicate that the character has not completed or carried out the task, and also cancel out Success symbols; Despair symbols count as Failure symbols indicate a spectacularly negative outcome or result, and cancel out Triumph symbols; and Threat symbols grant a negative side effect and cancel out Advantage symbols. Only Success and Failure results indicate whether or not a character has succeeded at an action—the effects of the Advantage, Triumph, Despair, and Threat symbols come into play regardless of whether the task was a success or not. Task difficulties range from one Difficulty die for easy tasks up to five for Formidable tasks, and in addition, certain abilities enable dice to be upgraded or downgrade, so an Ability die to a Proficiency die or a Challenge die down to a Difficulty die.

In general, the dice mechanics in the Genesys Narrative Dice System—and thus, Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas—are straightforward enough despite their complexity. They are perhaps a little fiddly to assemble and may well require a little adjusting to, especially when it comes to narrating the outcome of each dice roll.

Combat is more complex. Initiative is handled by a skill roll—using Cool or Vigilance, and attack difficulties by range and whether or not the combatants are engaged in melee combat. Damage is inflicted as either Strain, Wounds, or Critical Injuries. Strain represents mental and emotional stress, Wounds are physical damage, as are Critical Injuries, but they have a long effect that lasts until a Player Character receives medical treatment. When a Player Character suffers more Wounds than his Wound Threshold, he suffers a Critical Injury, and when he suffers Strain greater than his Strain Threshold, he is incapacitated. The various symbols on the dice can be spent in numerous ways in combat to achieve an array of effects. So a Triumph symbol or enough Advantage symbols could inflict a Critical Injury, allow a Player Character to perform an extra manoeuvre that round, and so on, whilst Threat and Failure symbols inflict Strain on a Player Character, three Threat symbols could be spent to knock a Player Character prone, and so on. Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas includes a table of options for spending Advantage, Triumph, Threat, and Despair in combat, as well as a table of critical Injury results. It does not, however, include a table for spending Advantage, Triumph, Threat, and Despair out of combat—a disappointing omission for anyone wanting to do a bit more with their character’s skills. That said, the Game Master should be able to adjust some of the options on the table to non-combat situations.

Lastly, the rules in Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas cover NPCs and Story points. Apart from nemesis-type NPCs, most NPCs treat any Strain they suffer as equal to Wounds, and Minions work together as a group. In Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible, there are two pools of Story Points—one for the Player Characters, one for the GM. They can be used to upgrade a character’s dice pool or the difficulty of a skill check targeting a character—NPC or Player Character in either case, or to add an element or aspect to the ongoing story. The clever bit is that when a Story Point is spent, it does not leave the game, but is shifted over to the pool of Story Points. So if the Game Master spends a Story Point to increase the difficulty of a Player Character’s Perception check to determine the motives of an NPC, she withdraws it from her own Game Master pool of Story Points and adds it to the players’ pool of Story Points. As a game proceeds and Story Points are spent and move back and forth, it adds an elegant narrative flow to the mechanics and will often force the players to agonise whether they should spend a Story Point or not as they know it is going to benefit the Game Master and her NPCs before it comes back to them.

A character in Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible has six characteristics—Agility, Brawn, Cunning, Intellect, Presence, and Willpower, plus a range of skills from Charm, Computers, and Cool to Ranged (attacks), Skulduggery, and Vigilance, as well as range of special abilities. The four pregenerated Player Characters include a Saurian Crœniac with a Cybersensor Implant for better perception and a hacking rig; a Human Discoverer whose Zoomclaw is a rocket-propelled grappling hook that both climbing tool and weapon; a Spirit Arbitrator, an incorporeal being clad in containment armour who was exiled from his knightly order for bounding with a sentient sword called Vizer; and an Elf of the Shadowws whose faerie companions aid him in mechanical tasks and acts of skulduggery. All four Player Characters are nicely presented in a busy, but easy to access character sheet.

Each Player Character also has a way to use Æmber, the golden, glowing substance found only on the Crucible—the setting for Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible—which is often processed to perform a single, specific function, such as currency. In its raw state it can be used to do strange and wondrous things. For example, Saurian Crœniac uses it to fuel a hazard field which makes attacks against more difficult, the Human Discoverer to make attacks with Zoomclaw jet-propelled, and so on. These are all one-shot abilities until the characters can obtain some more raw Æmber.

The setting for ‘Maw of Abraxas’, the scenario in Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is Crucible, the ‘Impossible World’, a Jupiter-sized world made up of innumerable different zones, each a different environment or climate. In effect, it is a multiverse in one place, a multi-genre setting made up of multiple settings. In ‘Maw of Abraxas’, the Player Characters will see just a few of them—a glass jungle, a tightly regulated agrisector, a lake wrought with multiple storms, and the ancient ruins of a lost civilisation. In the scenario, the quartet of heroes have been asked by their boss, the tentacular Fixer, to recover the Cube of Realities, a weird artefact with the capability of warping the world around its user. He wants to ensure that it does not fall into the wrong hands. Unfortunately, the militant, xenophobic Martians already have it, but to prevent it being stolen or falling into the hands of their enemies have hidden it aboard a prototype saucer ship which even they cannot track or scan for! However, contact with the saucer has been lost, but fixer has learned that its designer created a device, the Vez Q-37 Scanulator, which can detect where the saucer is. So all the Player Characters have to do is steal the Vez Q-37 Scanulator from a Martian base and fight their way out, get across several sectors by Teleporter Cannon and then a couple more by whatever means necessary, find the lost saucer ship and grab the Cube of Realities. Easy, right? Of course not!

Consisting of just three acts, ‘Maw of Abraxas’ begins by dropping the Player Characters in media res and never lets up on the action or pacing. It should provide a session or so’s worth of play and comes with suggestions as to what each Player Character could do in a scene, and showcases a little of the diversity of the Crucible as a setting. The Player Characters all feel very different and the adventure should give them each a chance to shine.

Physically, Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is very nicely presented, in full vibrant colour. The artwork is excellent, if a little busy in places, and the book is well written and easy to understand.

The one downside to Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is that it uses the Genesys Narrative Dice System and that means using propriety dice. Now on the weekend of Free RPG Day 2020, the dice app for Genesys was available for free and that was very generous of the publisher. Of course, if a group is already playing Genesys or Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible, and has either the dice or the app, then Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is easy enough to run and play, whether that is as extra scenario for an existing Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible campaign or as an introduction to the setting. If not, then Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is unplayable, which is a pity because it is a fun scenario, though of course, a Game Master might be inspired to get either dice or app after reading though it so that she can run the scenario.

That issue aside, Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible – Maw of Abraxas is an entertaining and fun introduction to Keyforge: Secrets of the Crucible. As a quick-start to both rules and setting, it is exactly the type of thing you want to pick up on Free RPG Day.

The Jewel in the Skull: ‘James Cawthorne: The Man and His Art’

Richard McKenna / September 17, 2020

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art

James Cawthorn: The Man and His ArtBy Maureen Cawthorn Bell

Jayde Design Books, 2018

Stuff has to happen when it has to happen, I suppose. Back in the summer of 2018, I’d pre-ordered a copy of James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art, but by the time it was released, the family health issues that had been increasingly dominating my life over previous years had consumed it completely. When the book arrived, I didn’t even leaf through it; just unwrapped it and stuck it on a shelf, registering only that it weighed a ton and must be hundreds of pages long. And perhaps because of its association with a sad time, I completely forgot about its existence for a couple of years, only finally opening it the other night on a sudden impulse. Would what it contained be powerful enough to burn off any negative personal associations and also not be the kind of dismal self-congratulatory fannery that makes you want to chuck all your books away and start getting into metalworking or something? Well, yes it would—James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art is absolutely fucking mind-blowing.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, Cawthorn was everywhere: the covers of his comic book adaptations of Michael Moorcock’s Elric stories were a fixture on the wall of every head shop, goth shop, comic shop, second-hand bookshop, and pawn shop I entered until I was in my mid-20s, and I’d grown up seeing his illustrations in things like New English Library’s Strange World of Science Fiction, the Savoy Books edition of Moorcock’s The Golden Barge, and the four kids’ sci-fi anthologies that Armada books put out in the 1970s. But, weirdly, it wasn’t until I sat down with this volume that I realized just how deeply his work saturates my own aesthetic life. Which is to say, my life. Not that I’m claiming my aesthetic or actual life are of two shits’ worth of interest to anyone except myself, of course, but it’s a strange feeling to suddenly realize that the blur that’s always been there at the edge of your attention is actually one of the spinning flywheels driving your mind—reminding you how many of those people existing on the margins of the culture remain marginal despite their contributions to shaping it. Cawthorn—who passed away in 2008—is a recognized figure among genre obsessives, but how did someone so interesting and idiosyncratic, who was once so ubiquitous, fall into such relative neglect?

Cawthorn was a child of the North East, an unfairly disregarded region of England, historically far from the money of London or Manchester, that has suffered massively since the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher set in motion the definitive closing down of the mines, heavy industry, and shipyards that had been the area’s backbone for centuries. As the final remnants of the steelworks and shipyards are gradually sold off to venture capitalists, that process of neglect is now pretty much complete, yet it’s a beautiful and magical place with its own strange magic, with deep links both to the ancient past and to the future—which makes sense, given how much of the future the locals dug, hammered, and welded together before they were sold out by the Tories. If you’re in any doubt about the North East’s futurist vocation, just remember that some of our culture’s most pervasive images of the future are the handiwork of another product of the region, one Ridley Scott, who certainly took inspiration from the vast petrochemical complexes lining local rivers (as anyone who ever flew into Teesside airport at night can testify). A self-taught, working-class illustrator, Cawthorn seems like a perfect reflection of that local genius, and in a way his relative anonymity mirrors that of his native land.

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art contains (apparently—I didn’t count) something like 800 color and black and white illustrations that cover his entire career. The contrast between the scratchy detail and dense chiaroscuro of his b&w work and the vaguely lysergic glow of his color art highlight how the two exist as entirely distinct entities, which, however, complement and complete one another when seen together here. And his color work also inspires the thought that perhaps Cawthorn’s relative oblivion is partly due to his style being too outsider-ey, too delicate and lurid (in a good way) to work at its best in the medium that was most lucrative and that offered most visibility during the time he was working—the paperback cover.

In fact, one striking thing about Cawthorn’s work is that it always retains the beauty of the obsessive amateur, never feeling glib or by-the-numbers. Even in the drawings that look most rushed, you can feel the commitment animating each piece—the euphoric sensation of watching cheap felt-tip pens somehow create entire new worlds. And unlike many other artists, Cawthorn’s aesthetic becomes more, not less, compelling and intense the more of it you see, as he endlessly mines and refines the mineral splendors of his own imagination in pursuit of his totally individual aesthetic. Looking through the book, it rapidly becomes clear that Cawthorn’s best-known images—to those who know them—aren’t even his most striking. In fact, it’s difficult to illustrate this review properly because some of his most memorable work doesn’t exist even in the daunting repository of everything that is the internet, and I don’t want to bugger up the spine on my copy.

The book has clearly been a labor of love for Cawthorn’s sister Maureen and publisher John Davey, and Maureen’s evocative and delicate memoir of him casts a lot of light on the personality behind the portfolio of artwork. Alan Moore and Michael Moorcock (a close friend of Cawthorn from his youth until Cawthorn’s death) both provide genuinely touching contributions, and the ever-reliable John Coulthart does a lovely job of arranging and presenting everything in a way that makes sense of the ridiculous amount of material, which ranges from the comics Cawthorn drew at school to the lovely t-shirts and birthday cards he produced in mind-boggling numbers for family and friends.

So like I said, James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art is absolutely fucking mind-blowing, a reminder of the violently surreal and inspiring power that imagery of this kind can possess when emptied of retrogressive cliché and self-satisfied rhetoric and filtered through a distinctive talent. It’s a potent inducement to pick up a pen, or a pencil, or a keyboard, or just anything, and put your imagination into use.

![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Portals and Presences: The Surreal Landscapes of Hipgnosis

Michael Grasso / September 16, 2020

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis CatalogueBy Aubrey Powell

Thames & Hudson, 2017

There’s always a danger of excessively romanticizing the era of the vinyl LP. Issues of sonic fidelity and durability aside, though, there’s one aspect of records on 12-inch wax that seemingly everyone does miss, and that’s the full-size record cover. Album covers during the heyday of psychedelic rock and roll were gateways to other worlds, their art often the province of esteemed painters and illustrators, their cryptic surrealism often filled with esoteric codes and symbols. Probably no other artistic collective was more famous during this decadent era than the London partnership known as Hipgnosis. From its edenic origins palling around with the rising stars of the late-’60s London psychedelic underground through to its mature period making iconic platinum album covers for global sensations like Pink Floyd, Paul McCartney, and Led Zeppelin, the creative forces behind Hipgnosis gained a rightful reputation as artistic visionaries whose work didn’t merely create identifiable brands and images for a musical group. Hipgnosis covers added to the mystique of the music, creating a visual component that rendered itself an indelible part of the listening experience.

“Album covers… defined you,” says Hipgnosis founder Aubrey “Po” Powell in his “Welcome to Hipgnosis” history in 2017’s Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue, a 300 plus page full-color hardcover monster that reproduces the collective’s entire album cover output from 1967 to 1984. “The covers gave an inkling of your personality, your musical tastes and preferences, and just how up to date and hip you were.” Powell, Hipgnosis’s photographer, met his creative partner Storm Thorgerson at a hashish-suffused party across the street from his rooming house (that was suddenly raided by the police) attended by much of Pink Floyd. In that afternoon, a bond was formed between Powell and Thorgerson, a graduate student in film at the Royal College of Art. In these swinging, soon-to-turn-psychedelic times, Thorgerson and Powell were at the center of a music and art scene that would break out of the cozy confines of a few odd students and onto the global stage. Named after a piece of graffiti that Floyd’s Syd Barrett scrawled on the door to their apartment in pen, Thorgerson and Powell’s partnership (Throbbing Gristle member Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson would join in the mid-1970s) created some of the most memorable album covers of the era.

Hipgnosis’s first rock client was Pink Floyd: seen here are three of their Floyd covers: the Dr. Strange-meets-real-life-alchemy of 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets, the recursive design of 1969’s double album Ummagumma, and the iconic 1973 cover for The Dark Side of the Moon.

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art . itself is equal parts fond (post-)hippie memoir and hard-nosed realistic account of what it was like to run a business in the often high pressure, big-money business of 1970s rock ‘n’ roll. The book contains a brief—if frank and fascinating—foreword from Peter Gabriel, who worked with Hipgnosis while leading Genesis and for his first three solo album covers. Throughout the hundreds of album covers, Powell provides a wry and informative running commentary on the personalities, problems, and sudden moments of inspiration—provided by both musicians and the cultural and natural environment—that contributed to Hipgnosis’s success. The Surrealist movement of the 1920s and specifically photographer Man Ray get quite a few name-drops in Powell’s assessment of the Hipgnosis catalog, and it’s easy to see why. The nude human form, out-of-place manmade objects juxtaposed with the organic, obvious, and often unnatural-looking photo collage: all of these definitive Surrealist techniques appear with frequency in Hipgnosis’s early output.

Much of the overall aesthetic of psychedelic rock took its inspiration from long-past artistic movements with Romantic, back-to-nature overtones: Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts, notably. With the surrealist edge of Hipgnosis’s designs, however, a flash of danger and alien weirdness was added to rock’s visual lexicon. Hipgnosis’s efforts at whimsical storybook-style covers for the Hollies and Genesis stick out like sore thumbs: solid efforts, but very much against the subversive grain of most of their work at the time. The covers where Hipgnosis unites Victorian twee with counterculture edge—such as using century-old techniques to hand-tint pastel color on Powell’s contemporary photos—do provide a pleasing synthesis of old and new.

Gentle nostalgic folkie Al Stewart’s understated style might not seem like it jibes with the fantastic scenes conjured on Past, Present and Future (1973) and Time Passages (1978). On the other hand, Dark Side of the Moon producer-turned-bandleader Alan Parsons’s 1978 album Pyramid was directly influenced by Parsons being “preoccupied with the Great Pyramid of Giza,” to the point of “obsession” and “out-of-body experience.”

But it’s not just the art movements of the past that provided Hipgnosis with ambient inspiration. The counterculture’s well-attested conscious fusion of old and new, of the esoteric with contemporary pop and outsider culture, including science fiction and comic books, is on display throughout the Hipgnosis corpus. One of their very first commissions, Pink Floyd’s 1968 A Saucerful of Secrets, very obviously embodies this fusion, with its mixture of images from “Marvel comics and alchemical books.” Powell and Thorgerson attest to their being “avid followers of Stan Lee… Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby,” all while recognizing that “in those heady days of 1968—a man was soon to land on the Moon, alchemy was a hot topic, extraterrestrials were a certainty, Tarot readings and throwing the I Ching were de rigueur—the search for enlightenment in the East was a definite must.”

Whichever way the cultural winds were blowing, Thorgerson and Powell always forged a link to the music in their designs. Even in cases where the imagery looks too mystically epic or weird for the music on the disk, such as the covers for Scottish folk musician Al Stewart’s Past, Present, and Future (1973) and Time Passages (1978), the music’s overall themes—remembrance, nostalgia, prophecy, and folk memory—contain a tenuous throughline justifying figures leaping through strange mystic portals or tuning into a radio station that glitches out all of reality. All these strains of the magical and surreal, from Renaissance alchemists to haunted Victorian portraitists to avant-garde plumbers of the post-World War I collective unconscious to Dr. Strange and the Silver Surfer—Hipgnosis synthesized these with the subconscious themes of the music to create visions that defied reality. Powell’s photographic eye and Thorgerson’s dreamlike visions found common cause in composing images that looked like set pieces on strange alien worlds or in magical faerie realms. But even with all the photographic trickery and post-production flourishes available to them as they moved out of student darkrooms and into their own studio, Hipgnosis still found inspiration out there on our Earth’s weirdest real-life spots. From the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland to a cracked, dry Tees estuary in the North of England to deserts in North Africa and the American West, Hipgnosis’s most memorable landscapes are worlds where something has gone awry, where weird monuments, alien beings, and strange hauntings abound.

Hipgnosis had a knack for using unique real-world backdrops to create eerie scenes for their album covers. Italian rock progressivo group Uno’s self-titled 1974 album depicts a mysterious hieratic harlequin with a glowing geodesic dome for a brain emulating the pose of the famous English chalk figure, the Long Man of Wilmington.

Of course there are the usual stories of rock star excess in the book, with the personnel from Hipgnosis being flown all across the world for photo shoots and consultations with the biggest names in ’70s corporate rock. In many cases, the musicians and managers themselves couldn’t resist being part of the process. Paul McCartney enjoyed hamming it up on the cover of Band on the Run, and a few years later Macca wanted to be the one to personally place the giant letters on a London theater marquee for the cover of Wings At The Speed Of Sound. Noted hard case Peter Grant, the imposing manager of Led Zeppelin, was giddy—he “burbled with glee,” according to Powell—over Hipgnosis’s proposal for a worldwide scavenger hunt of a thousand replicas of the eerie totem from the cover of 1976’s Presence. One could argue that Hipgnosis, Led Zeppelin, and Peter Grant invented the music industry alternate-reality game in 1976 (sadly, the surprise Presence publicity stunt never got off the ground after it was leaked by the music trades).

Powell is honest throughout the book about the various misfires; he finds some of their ideas in ridiculously poor taste upon reassessment and most modern observers would be hard-pressed to disagree. The collective’s pinpoint arch visual humor certainly sometimes misses the mark. If I were to sum it up: the Hipgnosis catalog contains a few dozen stone-cold classics, a bunch of forgettable designs, and a few that look like rejects for Spinal Tap’s album Shark Sandwich. Hipgnosis’s wit was used to best effect when channeling those common cultural currents mentioned above: for example, 10cc’s classic cover for their album Deceptive Bends—the creation of which is broken down in great detail by the late Thorgersen in a contemporary piece from 1977 included in the book—talks about the physical and logistical challenges in place from the beginning but also places the imagery of the diver carrying the helpless damsel in its proper context with “monster” B-movies like Creature From the Black Lagoon (1954) and Robot Monster (1953). Trawling our collective pop culture unconscious, Hipgnosis called forth all kinds of creatures from the deep over their less than two decades on Earth, creatures that walk amongst us long after the collective’s demise.

![]() Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Feliks Jabłczyński - Mephisto, 1893

A Coke and a Smile: Tsunehisa Kimura’s ‘Americanism’