Witch Week Review: Kids on Brooms

Let's go with one I have had since the Summer. I love the concept and can't wait to see what I do with it.

Kids on Brooms

Kids on BroomsBefore I get too far into this review I want to start off by saying how much I love the art by Heather Vaughan. It just fits, or more importantly sets, the tone of this book. This could have been a cheap "Harry Potter" knock off, but Vaughan's art makes it feel darker and more dangerous. The kids in her art have power, but they also have fear, and even a little hope. So kudos to Vaughan for really setting this book up for success from the cover and into the book.

Again for this review, I am considering the PDF from DriveThruRPG and the physical copy I picked up at my FLGS.

The game is 96 pages, roughly digest-sized. The art is full color and used to great effect. The layout is crisp and clean and very easy to read.

Kids on Brooms (KoB) is a new (newish) game from the same team that gave us Kids on Bikes. Authors Doug Levandowski and Jonathan Gilmour with artist Heather Vaughan. New to the team is author Spenser Starke. If Kids on Bikes was "Stranger Things" inspired then the obvious inspiration here for Kids on Brooms is Harry Potter. If it were only a Harry Potter pastiche then there would be nothing to offer us.

The game follows in the footsteps of many newer games in that narrative control is shared. The players help decide what is going on. So our Session 0 for this game is to have the players come up with their school. This can be just about anything to be honest, Harry Potter's Hogwarts is the obvious model, but I also got some solid Night School from Chilling Adventures of Sabrina as well. Also, I could see a Breakbills Academy easily being created here, though the characters in Magicians were older. These students are very much of the 12+, highschool age, variety.

The players create their school and even provide some background history and some rumors. It all looks rather fun to be honest. This section starts with the first of many questionnaires to do your world-building. None are very long, but they are rather helpful to have. I should point out that prior to this school building you are tasked with setting the boundaries of the gameplay. What is and what is not involved. A LOT of people think this is a means to stifle creativity. It is not. It is a means to keep everyone at the table comfortable and playing what they want. I mean a drug-fueled sex party prior to a big magical battle is not something you would find in Harry Potter, but it is the exact sort of thing that happens in Magicians or Sabrina.

Something else that is a nice added touch is talking about the systems of power in the game world. So figuring out things like "This form of bigotry exists (or doesn't) in the game world and is different/same/better/worse than the real world." To quote Magicians, "magic comes from pain." Happy people in that world are not spell-casters. Quentin, the star, was depressive and suicidal. The other characters had their own issues, or as Quentin would say "we are fucked in our own ways, as usual." To ignore this page is to rob your game of something that makes your world fuller.

Character creation is equally a group effort, though the mechanic's piece of it is largely up to the player. The player selects one of the Tropes from the end of the book, these are only starting points and are more flexible than say a D&D Class. You introduce your character (after all they are young and this is the first day of class) and then you answer some questions about your character to build up the relationships.

Mechanics wise your six abilities, Brains, Brawn, Fight, Flight, Charm, and Grit are all given a die type; d4 to d20, with d10 being average. You roll on these dice for these abilities to get above a target number set by the Game Master.

As expected there are ways to modify your rolls and even sometimes get a reroll (a "Lucky Break"). The "classes" (not D&D, but academic levels) also gain some benefits. You also gain some strengths and flaws. So if it sounds like there are a lot of ways to describe your character then yes! There is.

There is a chapter on Magic and this game follows a streamlined version of the Mage-like (as opposed to D&D-like, or WitchCraftRPG-like) magic system. You describe the magic effect and the GM adjudicated how it might work. Say my witch Taryn wants to move a heavy object. Well that would be a Brawn roll, but I say that since her Brawn is lower and instead I think her Grit should come into play. So that is how it works. Rather nice really.

At this point, I should say that you are not limited to playing students. You can also play younger faculty members too.

Filling out the details of your character involves answering some questions and getting creative with other ideas. You also fill out your class schedule, since there are mechanical benefits to taking some classes.

The mechanics as mentioned are simple. Roll higher than the difficulty. Difficulty levels are given on page 45, but range from 1 to 2 all the way up to 20 or more. Rolls and difficulties can be modified by almost anything. The first game might involve the looking up of mods and numbers for a bit, but it gets very natural very quickly. As expected there are benefits to success above and beyond the target difficulty numbers and consequences for falling short of the numbers.

Some threats are covered and there is a GM section. But since a lot of the heavy lifting on this game is in the laps of the players the GM section is not long.

There is also a Free Edition of Kids on Brooms if you want to see what the game is about. It has enough to get you going right away.

This game is really quite fantastic and there is so much going on in it. Personally, I plan on using it as a supplement to my own Generation HEX game from NIGHT SHIFT.

Plays Well With Others, Generation HEX, and my Traveller Envy

I am SO glad I read this after I had already submitted my own ms in for Generation HEX in NIGHT SHIFT.

Thankfully I can see a game where I would use both systems to help expand my universe more. The questionnaires here for both the school and the characters would also work well for a Generation HEX game. In this case though everyone knows about magic and the school is AMPA. OR Use the background of the hidden school like in KoB and then add in some GenHEX ideas.

So let me take another character today, Taryn, Larina's daughter. Taryn is my "Teen Witch" and a bit of a rebel. She was my "embrace the stereotype" witch, but has grown a little more since then. Compared to her mother her magic came late (Larina was 6, Taryn was 12) so she feels like she has a lot to make up for. Her father is a Mundane and her half-sister has no magic at all.

Taryn is cocky, self-confident, but also a little reckless. Now that she has magic she is convinced it can solve all her problems. She feels she has a lot to prove and is afraid there is some dark secret in her past (spoiler there is).

She spends her nights in an underground, illegal broom racing circuit. She is very fast and has already made a lot of cash and a few enemies. She is worried that one of her secrets, her red/green colorblindness, will affect her races.

Her other weakness is guys on fast motorcycles. She is particularly fond of the Kawaski Ninja Carbon. Yeah, she judges people based on their bikes.

Speed is her addiction of choice. Not the drug, the velocity. Though that might be an issue in the future.

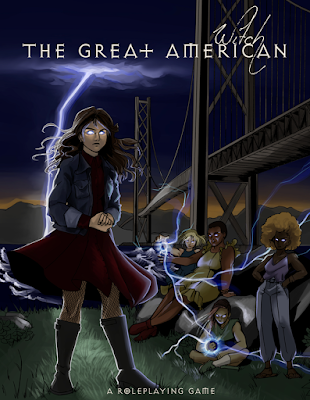

I find I am able to depict her rather well in Kids on Brooms, NIGHT SHIFT and Dark Places & Demogorgons. I even gave her a try in the Great American Witch (she is Craft of Lilith).

This game has a bunch of solid potential and I am looking forward to seeing what I can do with it.

Snowbeast

Snowbeast