1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that

Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version,

Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles—and so on, as the anniversaries come up. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

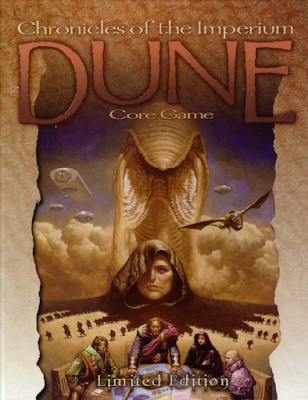

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium was published by Wizards of the Coast in the year 2000. With the forthcoming

DUNE: ADVENTURES in the IMPERIUM roleplaying game from

Modiphius Entertainment as well as a new film directed by Denis Villeneuve, the 2020 is the perfect time to re-examine the hobby’s first attempt to bring Frank Herbert’s seminal Science Fiction work to tabletop roleplaying. That Wizards of the Coast published

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium in a limited release is something of surprise, for it had originally been designed by Last Unicorn Games, a publisher best known for its three, highly regarded roleplaying games based on the

Star Trek franchise. When Wizards of the Coast purchased Last Unicorn Games, it agreed to publish the roleplaying game, but declined to renew the licence with the Herbert Estate and so there it ended.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium, limited to just three thousand copies, was destined to become a collector’s piece, often selling for hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars. It would never get a reprint and the supplements announced in its pages, including

Federated Houses of the Landsraad and

The Spacing Guild Companion, would never see print. Similarly, a

d20 System version of

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium from Wizards of the Coast would not see print either, although one of the designers did release

The Voice from the Outer World, Chapter One, an excerpt from what would be one the first adventure.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is set before the events of the first novel,

Dune. The Imperium has ruled mankind across the Known Universe for some ten millennia following a fierce anti-technological backlash—the Butlerian Jihad—which led to the rejection of all thinking machines and the profound development of the human potential. Over the centuries since these have coalesced into several great schools—the Spacing Guild, many of its members forcibly evolved into the Guild Navigators capable of folding space and enabling interstellar travel; the Bene Gesserit sisterhood and its genetics programme to protect humanity; the Mentat school, its graduates capable of great acts of computation and analysis; the Suk Medical School, its doctors incapable of harming their patients due to their ‘imperial conditioning’; and the Swordsmaster’s School of Ginaz, its graduates peerless soldiers and duellists.

For millennia, power in the Imperium has rested on several pillars. These are the Padishah Emperor, backed by his elite Sardaukar military forces; the Landsraad Council which represented the Imperium’s Great Houses—was headed by the Emperor; and CHOAM—or Combine Honnete Over Advanced Mercantiles—the great mercantile body which controlled the Imperium’s economy and every product or service manufactured, sold, and purchased. Most of the Great Houses hold directorships in CHOAM as well as their fiefdoms from the Emperor. The most important of these products is the Spice melange, which is only mined on the planet Arrakis, and as well as its anagathic properties, also enables the Guild Navigators to fold space. The last pillar is the Space Guild, which holds a monopoly on space travel and maintains a strictly neutral stance when it comes to Imperial politics.

Although the Imperium is at peace and open warfare is rare, both the Great Houses and the Houses Minor feud with each other, sometimes over rivalries going back to the foundation of the Imperium. The Rules of Kanly guide negotiations and diplomacy, but also govern how the Houses wage war on each other—typically through formal duels, assassination, and political hostage-taking and ransoms. These rules are very likely to play a great role in any campaign of

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium, because the default set-up for such a campaign is to cast the Player Characters as members of the Entourage belonging to a House Minor allied to one of the Great Houses. They will be House Adepts of the Bene Gesserit, House Assassins, House Strategists, House Mentats, House Nobles—perhaps even the heir, House Swordmaster, or House Suk. This leaves a lot of character options, whether that is Fremen Warrior or spice smuggler, to be covered in other supplements—which of course, never appeared.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium presents six Great Houses—three known and three new—to which the Player Character House Minor can ally—and three Houses Minor for each. The three Great Houses are House Atreides, both feted and hated for its leadership, courage, and morality—and whose fortunes are the subject of the novel; House Corrino, the Imperial House which sits on the Golden Lion Throne and which fears the influence of the Atreides; and House Harkonnen, the rapaciously mercantile and treacherous enemies of the Atreides. The three new Great Houses are House Moritani, which successfully waged a War of Assassins against House Ginaz and now occupy the world of Grumman; House Tsieda, a withdrawn and traditionalist House which specialises in legal consultation and representation; and House Wallach, a military House staunchly loyal to the Emperor. Each of the six Great Houses is given a solid write-up, whilst allied Houses Minor are given shorter, though enough to develop more details from, descriptions, and one is given full stats.

Alternatively, the Game Master and her players could create their one House Minor. Each House Minor is defined by four Attributes, each of which has two Edges, or particular talents related to the attributes. The Attributes are rated between one and five and the Edges between minus two and plus two. The House Attributes and their Edges are Status plus Aegis and Favour, Wealth plus Holdings and Stockpiles, Influence plus Popularity and Authority, and Security plus Military and Intelligence. A House Minor also has an Ancestry, including Name and Homeworld, a Title and a Fiefdom, Renown, and Assets. The Fiefdom can anything from a City District to a Subfief, and the Title from Magistrate to Siridar Governor or Baronet. To create a House Minor, a House Minor Archetype is selected from a choice of six—House Defender, House Pawn, House Favourite, House Reformer, House Pretender, and House Sleeper—which provide the base stats for House Minor, and fifteen Development Points are spent on various House aspects.

—oOo—

House Molo claims its origins date back to before it was granted to House Harkonnen. Its relationship with its liege has always been rocky and House Molo has long agitated under the Harkonnen grasp, almost to the point of rebellion on a number of times. To date, the Imperial Charter granted to the Tormburg School of Engineering—famed for its petrochemical and chemical engineers—has afforded the House Minor a degree of protection as has a number of careful marriages. The family has a strong tradition of fielding arena champions, which goes to back to the clan matriarch, Althena IX von Molo, successfully settling a legal dispute with the House Minor’s liege, the Harkonnens, some centuries ago. House Minor von Molo has also fielded champions on behalf of other Houses Minor on Gedi Prime and consequently, it is not unknown for the Harkonnen Barons in frustration to appoint von Molo champions to represent its enemies. House Minor von Molo is all but loyal to the Harkonnens, but wants better treatment for the populace and less avaricious policies.

House Minor Profile

Name: von Molo

Ancestry: Harkonnen

Homeworld: Gedi Prime

Title: 3 (Siridar-Ritter)

Fiefdom: 2 (Free-City of Tormburg)

Renown: 1

Assets: 5

Attributes (House Sleeper archetype)

Status: 3

Wealth: 3 (Stockpiles +1)

Influence: 2 (Authority -1, Popularity -1)

Security: 3 (Intelligence +1)

—oOo—

The stats for the Player Characters’ House Minor come into play during ‘Interludes’, the periods between adventures when both players and the Narrator conduct a ‘Narrative Debriefing’ during which they can discuss how the Player Characters’ actions furthered their House’s goals, the aim having been to complete anyone of a number of Narrative Ventures. These might be an act of diplomacy or political campaign at the Sysselraad—the planetary equivalent of the Lansraad for all of the Houses Minor on a planet, training military forces, intelligence or counter-intelligence manoeuvres, investing in a business venture, and so on. Mechanically, they require investment upon the part of the players using the House Minor’s Asset points and their success depends upon a Test similar to Skill Test. However, the rewards are simply numerical—more Asset points to spent on developing the House Minor. Arguably there is a missed opportunity here to present something more interesting and more involving, perhaps not dissimilar to what Green Ronin Publishing did for

A Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying, the RPG based on the fantasy works of George R.R. Martin. Perhaps more interesting and more involving would have been published in the unpublished

Federated Houses of the Landsraad?

A character in

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is defined by Attributes, Edges, Skills, Traits, Renown, Caste, and Equipment. There are five Attributes, and each has four Edges. The Attributes are rated between one and six—the latter the limits of Human potential, and the Edges between minus two and plus two. The character Attributes and their Edges are Physique plus Strength and Constitution, Coordination plus Dexterity and Reaction, Intellect plus Perception and Logic, Charisma plus Presence and Willpower, and Prescience plus Sight and Vision. Skills are rated between one and five, and typically require a specialisation, for example, Culture (House), Computation (Straight-Line), and BG Way (Petit Betrayals). It should be pointed out that the skill list is fairly extensive, and there is no little nuance to them, especially in the Specialisations. For example, the Statecraft skills has the Specialisations of Artifice, Equivocation, Mind Games, and Perjury. In addition, there is some overlap between some Skills and Specialisations, such as Statecraft (Threats), Interrogation (Coercion), and Racketeering (Extortion), which could be used to blackmail or intimidate an enemy—all depending upon the circumstances, of course. Now this is can either be interpreted as too many skills or it could simply be a matter of nuance and as well as circumstances, could represent differing approaches to a task. A nice touch is how example difficulties are given for each skill.

Of course,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium being set in the

Dune universe, it needs certain skills to reflect the special abilities of graduates of schools such as the Mentat and the Bene Gesserit. So for the Mentat there is Computation, Mentat Trance, and Projection, whilst for the Bene Gesserit, there is BG Way, Ritualism, and Voice. Also included are the Prescience and Prophecy Skills, which when used grant glimpses of the future. Apart from the latter two Skills—since they are less likely to appear in a campaign—these all do feel as if they are could use further development and explanation. As useful as the example difficulties given to each skill description are, one thing that is missing is explanations of what the Specialisations are. In general, this is not a problem, it can in some cases leave Narrator and player alike scratching their head. For example, the Mentat Computation Skill has the Specialisations of Probability Computation, Straight-line computation, and Comparative Induction, whilst the Projection skill has the Approximation Analysis, Factual Analysis, Proximity Hypothesis, and Zero-bias Matrices Specialisations, but in neither is there any explanation of how they work or what they are. Given that the Mentat will have these Specialisations, it is frustrating to have them explained. In the short term, the Narrator could probably have said that more information was forthcoming in a supplement—perhaps the

Narrator’s Guide?—but not in the long term.

Traits are advantages or disadvantages, such as Bimanual Fighting, Latent Prescience—necessary to raise the Prescience Attribute to one and to be able to choose its associated Skills, Shield Fighting, Addiction, Human—meaning you have been tested as the Bene Gesserit, Genetic Eunuch, and so on. Some Traits are particular to certain Schools, such as Prana-Bindu Conditioning, Truthsaying, and Weirding Combat for the Bene Gesserit, Imperial Conditioning and Pyretic Conscience of the Suk Doctors, and Machine Logic and Mental Awareness of the Mentats.

Every character will have a place on the ‘Faufreluches’ or Imperial caste system. The Emperor, the Imperial Family, the Great Houses, Houses Minor, and so on, are Regis-Familia. Most Player Characters will Na-Familia—named family, Household vassals, or Imperial citizens, or Bondsman—Bonded Professionals.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is not a roleplaying game which dwells particularly on equipment, though there is some discussion of it since it has distinct ramifications upon play, whether that is the use of melee weapons or slow projectile weapons against opponents wearing shields—infamously, shooting a lasgun at a shield can result in an atomic explosion, or the need to contract the Spacing Guild to travel from one star system to another. In general though, a Player Character will have whatever he needs to do his job.

Once the players and Narrator have decided upon or created their House Minor, each player can create his character who will be part of the House Minor’s Entourage. Three methods are provided to create a character. The first is to choose one of the seven pre-generated templates—House Adept, House Assassin, House Strategist, House Mentat, House Noble, House Swordmaster, and House Suk—and then personalise it a few Development Points. The second is to build it out of a series of four packages and overlays. These consist of a character’s House Allegiance, which determines which Great House the House Minor is allied to and his base Attributes, Skills, and Traits; Vocational Conditioning, such as Bene Gesserit Adept or Master Strategist; and a Background History package like Mentat Priming or Slave Pits, House Service like Personal Confidante or Warmaster, ad Personal Calling like Advocate or Sleeper Agent. Lastly, a player has a few Development Points to personalise his character with, and his Caste and Renown to set. The third method is point-based, a player being give one-hundred-and-thirty Development Points to spend. This is the longest and most complex method.

—oOo—

Olifer Taheri grew up in the notorious Harkonnen slave pits on Gedi Prime. He not only survived, but was part of a rebellion in his youth. This was put viciously by the planetary police and many of Olifer’s friends were killed, even butchered. He was captured and thrown into the arenas to fight again and again until he was killed. Not only did he survive, but defeated his first opponents, and eventually he gained some notoriety. House Harkonnen came to hate him and was planning to execute for his ‘crimes’ during the slave rebellion, but House Molo instead offered to purchase him. The Harkonnens did, and House Molo sent him to Ginaz. Currently he serves as the House Swordmaster and takes pleasure defeating Harkonnen fighters in the arena.

Olifer Taheri

House Allegiance: House Harkonnen

House: Molo

Vocational Conditioning: Swordmaster

Background History: Slave Pits

House Service: Weapons Master

Personal Calling: Arena Fighting

Attributes:

Physique 2 (Constitution +1, Strength +1)

Coordination 4 (Reaction +1)

Intellect 2 (Perception +1)

Charisma 2 (Presence +2, Willpower +1)

Prescience 0

Skills:

Armament 3 (Operation 2, Repair 2)

Armed Combat 3 (Duelling 4)

Athletics 2 (Climbing 1, Running 1)

Charm 1 (Flattery 1)

Culture 1 (Harkonnen 1)

Dodge 4 (Evade 2, Sidestep 1)

First Aid 1

History 1 (Harkonnen 1)

Leadership 2 (Guerrilla Operations 2)

Military Operations 2 (Guerrilla Warfare 2)

Observation 1 (Search 1)

Politics 1 (Harkonnen 1)

Ranged Combat 2 (Stunner 1)

Security 1 (Systems 2)

Stealth 1

Survival 1

Unarmed Combat 3

World Knowledge 1 (Gedi Prime 1)

Traits

Alertness 1, Bimanual Fighting 2, Duelling 3, Heroism 2, Information Network 1, Resilience 1, Shield Fighting 1, Whipcord Reflexes3, Code of Conduct +3

Renown: Valor 1

Caste: 3 (Bondsman)

Karama: 3

Equipment: House uniform, personal shield, slip-tip, stunner, sword

—oOo—

Mechanically,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium uses the

ICON System, as used in Last Unicorn Games’

Star Trek: The Next Generation,

Deep Space Nine, and

Star Trek Role Playing Game. It is a six-sided dice mechanic. To undertake an action a player rolls a number of dice equal to an Attribute plus an applicable Edge, one which should be of a different colour. This is the Drama Die. The player takes the highest value rolled on the dice and adds the Skill to get a total. This is compared to a Test Difficulty, which ranges from four or Routine all the way up to thirteen or Difficult. If a six is rolled on the Drama Die, then the player can use that and add the result of the next highest die to the total. Rolling a six on the Drama Die will typically result in a critical success, whilst rolling a one on the Drama Die and not succeeding, a grievous failure.

For example, Olifer Taheri is attending some arena games with his master, Tobias Molo and they are accompanying Adan Fosconi, the Master of the Arena on a tour of the training area. Fosconi asks Taheri his opinion of the fighters there and the swordmaster decides to flatter the Arena Master. The Narrator describes this as a Routine Test, giving Taheri a Difficulty number of six. Taheri’s player will be rolling a total of four dice, two for his Charisma and another two for his Presence Edge. He will be adding one for his Charm Skill and one for his Flattery Specialisation. Taheri’s player rolls one, three, six, and six on the Drama Die. This means he adds the next highest value die—also a six—plus Taheri’s skill for a total of fourteen. This is an exceptional roll and being both six higher than the Difficulty and a six was rolled on the Drama Die means that a critical success has been scored. Master Fosconi laps up Taheri’s praise and is already thinking of how much money he can win by betting on his fighters in the arena that afternoon.In addition, each Player Characters also has Karma, which can be spent on a one-for-one basis to modify the results of Test. However, he will only have a few points and this may not be enough given how difficult it is to roll overcome a Moderate or Test Difficulty of seven if a character has a low skill value, and a Challenging or Test Difficulty of ten or more with medium or high skill values. The problem here is that rolling high is dependent on roll a six on the one die—the Drama Die. Thus, rolling high is a relatively rare occurrence. Otherwise, the

ICON System is generally simple and easy to use.

In comparison, combat in

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is much more complex. Its focus is on personal combat and it leaves the larger combats, guerrilla actions or other acts of warfare to be handled as House Ventures. What this means is that combat is tactically rich, but strategically poor, which undermines so much of what the roleplaying game is about—the fortunes of a House Minor and the Player Characters’ involvement in that. The rules do cover elements particular to the

Dune universe, and much like the setting there is an emphasis on melee combat and duelling. So the Duelling Trait grants access to various special manoeuvres in combat, as does Shield Fighting, which teaches a fighter to be slower in combat in order to penetrate an opponent’s shield, but penalises them when unshielded, because he trained to be slow. The Bene Gesserit have their own form of martial arts, called Weirding Combat.

Mechanically, combat is not merely a matter of trading blows back and forth from one round to the next. Combatants receive a pool of Option Points to spend on manoeuvres in combat, but effectively this pool becomes two, because each combatant will be spending and tracking points spent on two types of manoeuvre Option—Actions and Reactions—and each combatant can spend an equal number of points on both. Actions include Aim, Hand attack, Slow Attack, and Autofire, whilst Block, Parry, and Riposte, are Reactions. Some can be both, such as Attack Sinister and Slow Sinister Attack. With each subsequent manoeuvre—Action or Reaction—the cost in terms of Action Points goes up, and as long as a character has Action Points to spend, he can act. Traits such as Weirding Combat and Duelling grant access to particular subsets of manoeuvre, invariably better than the standard attack and defensive manoeuvres. The range of manoeuvres available in combat is what makes combat so tactically rich and used effectively, it can reflect the cut, thrust, block, counter strike, and more of a duel or combat. Although it helps that there is extensive example of combat in the rules, there is no denying their complexity and the fact that they give a lot for both Narrator and player to keep track of from round to round.

For example, later the same day at the arena, Adan Fosconi, the Master of the Arena enraged at the loses made on the bets he placed on his gladiators decides to take his revenge by sending some thugs to beat up Olifer Taheri and perhaps even kidnap his master, Tobias Molo. Olifer Taheri has the Alertness Trait and the Narrator has rolled in secret to determine if the swordmaster spots the thugs. He does and with a shout of, “Get behind me, my lord!”, reaches down to his belt to activate his shield and draw his sword and dagger. Taheri’s Initiative is equal to his Coordination of 4 and Reaction +1, so a total of five, and this is also the number of Option Points his player has to spend. The Criminals have Coordination of 2 and Reaction +1, so have three Initiative and three Option Points. The Narrator declares that the first action of the Criminals is to Attack. This costs them one Option Point each, leaving one point remaining for Attack Options and three for Reaction Options. Taherio declares that his is to Parry Sinister, a Reaction which will cost him one, leaving five points remaining for Attack Options and four for Reaction Options. The Narrator rolls for the first Criminal—two dice for his Coordination of 2 and adds his Armed Combat of 3—and gets a total of eight. Tehari’s player rolls five dice for his Coordination of 4 and adds his Armed Combat of 3 and Duelling of 4. His total of ten easily beats the Criminal’s eight, and Tehari blocks the attack with his dagger. Tehari then declares a Riposte. This has a cost of one, but because he has done one Reaction, its cost goes up to two, leaving him with two for Reaction Options. The Narrator states that the first Criminal will attempt to Dodge, which will set the Difficulty Test for Tehari’s Riposte. The Dodge will leave the Criminal with one point for Reaction Options. The Criminal rolls three dice—two for his Coordination of 2 and one for his Reaction +1—and adds the Criminal Dodge Skill of 1. The Narrator rolls a total of 6. Tehari’s player rolls four dice for his Coordination of 4 and adds his Armed Combat of 3 and Duelling of 4. Unfortunately, Tehari’s player rolls a total of 13. This is more than the Criminal’s Dodge value and likely a critical hit, so the first Criminal is probably badly hurt. However, there are still two other Criminals to Tehari to defeat and they have not attacked yet…In terms of background,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium provides a history of the Imperium—though no timeline, a discussion of the Great Convention which keeps the peace, details of six of the Great Houses and their worlds, technology and equipment, the Great Schools, and some of the personages of the Imperium. It is overall, a good overview, but in the long term will likely be found wanting as the Narrator wants more information. Where there is focused information is in the presentation of ‘Chusuk, the ‘Music Planet’’, which gets a whole chapter of its own. This is the presentation of a single planet as an example setting, Great House, and Houses Minor. It is home to a relatively new Great House, House Varota, renowned for its musicianship, craft as instrument makers, its devotion to the arts, and also spies. Chusuk is also home to a notable religious sect, the Navachristians. It is a good example of what a Narrator could come up with as a world for his own chronicle and showcases perhaps what a supplement devoted to the worlds of the

Dune universe would have looked like. It is followed by short scenario in its own chapter, ‘Instrument of Kanly’, which continues the musical theme and sees the Player Characters’ Entourage come to Chusek in search of a stolen musical instrument. Again, this is a decent, a low-key adventure suitable for beginning players and characters, only really let down by the fact that it is the first part of a two-chapter story arc. It involves lots of diplomacy, interaction, treachery, and some combat, effectively showcasing various elements of the rules, and along the way, allowing the authors to have fun with some musical puns. That said, both chapters containing the adventure and the planetary description do feel out of place in the middle of the book.

In addition, the Narrator is given not one, but effectively two chapters on how to be a good Game Master. ‘Chapter VI: A Voice from the Outer Void’ is general advice, covering how to set a scene, using the mechanics, keeping the players interested, and so on. It is useful, solid advice. It is followed by ‘Chapter VII: Pillars of the Universe’ which delves into themes and ideas particular to

Dune—Human Conditioning, Plans within Plans, Preservation of Bloodlines, Messianic Prophecy, and more, before going on to discuss how to create a chronicle of the Narrator’s own. The discussion of the themes and ideas is fascinating, but ultimately feels too short. Hopefully the release of a supplement like the

Narrator’s Guide would have presented these subjects in much more of the depth they deserved, but of course, this was not to be.

Physically,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is very nicely presented. There is plenty of artwork, much of it very good, the book is generally well written, and well laid throughout. No little thought has been given to the organisation of the book thematically. So, the book is divided into ‘Book One: Imperium Familia’, introducing the setting and rules, and ‘Book Two: DUNE Oracle’ and ‘Book Three: Imperial Archives’ providing more background and a scenario. Then Skills and Traits are organised thematically into Valour of the Brave, Learning of the Wise, Justice of the Great, and Prayers of the Righteous—covering physical and combat, knowledge, political and social, and other Skills and Traits respectively.

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is a fantastic game, there is an undeniable depth to its treatment of the Frank Herbert’s

Dune universe—which comes the quantification necessary when designing and playing a roleplaying game, it enables players to create characters which feel right for the setting, it provides a decent enough of background, and it provides both a reason to play in what the player characters do and something for them to play in the form of the scenario. However, that background is unlikely to be enough to support a campaign in the long term, especially when delving into the intricacies of the Bene Gesserit or the Mentats, and the other Great Schools, and much of the background is not presented in an easy-to-use fashion—for example, there is no chronology attached to the extensive history. The focus of

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is also narrow in terms of what you can play, the types of campaign, and the scope of the background—Arrakis is very much an afterthought and it is not possible to create characters from there with any ease. The rules feel overwritten in places, for example, in the number of Skills available, and underwritten in others, in their explanation, whilst the ICON System does not feel quite up to the task. Nor do the rules effectively support or explain the House progress through the use of the House Ventures, which is disappointing given the fact that the

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is all about roleplaying the fortunes of a House Minor.

Today,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is a collector’s piece, worth no little amount of money. Unless you are a collector or an avid fan of the

Dune setting, it probably is not worth your having. As a roleplaying game,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is everything that want to start playing the

Dune universe—characters, background, advice, starting adventure, and more. Only in a particular way though—as a House Minor Entourage—but a resourceful playing group could deconstruct the rules to run other games in the

Dune universe with some effort. However, as written, the scope of

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium is limited, indeed the clue is on the front cover where it says, ‘Limited Edition’, and any Narrator would probably exhaust those limitations fairly quickly. This is not necessarily the fault of the

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium Core Rulebook itself, which really should be seen the starting point for the rest of the line, just as with any other roleplaying game. Although underdeveloped in places,

Dune: Chronicles of the Imperium successfully gives you the means to roleplay in the

Dune universe and makes the setting a believable one to roleplay in, both for fans of the

Dune universe and roleplayers in general, but ultimately, its potential will remain lost and untapped.

The Ecotopians are much more cagey about whether their society is “socialist” or not; certainly, the seizure of corporate capital in the first months of the Ecotopian revolution qualifies as classically socialist (“the forced consolidation of the basic retail network constituted by Sears, Penneys, Safeway, and a few other chains,” Weston notes), but Ecotopia is more properly classified as a mixed economy, as a private market and currency backed by a central bank does still exist. But it’s clear that at its base, Ecotopia is an essentially syndicalist-socialist state, with self-determination regarding labor being its organizing principle. Small groups of people numbering in the few dozens spontaneously form communes, farms, factories, educational foundations, and research facilities based on their common interests and goals. In addition, work assignments change depending on need and demand; students spend more time in university trying out different occupations, and every Ecotopian inevitably ends up owing service to their society outside their own job. The nuclear family has been largely upended by the Ecotopian revolution, with Ecotopian children raised by their “village.” On the larger scale, Ecotopian living communities are smaller and more self-contained. Along with the nuclear family, the commuter suburb has been destroyed in favor of self-sufficient “ring towns” surrounding larger urban conurbations, all linked by low-pollution high-speed trains. These basic changes in living structures have, within a generation, altered the Ecotopian psyche deeply. There is a greater openness to experience and to emotion, a greater sense of the interconnectedness of all Ecotopians.

The Ecotopians are much more cagey about whether their society is “socialist” or not; certainly, the seizure of corporate capital in the first months of the Ecotopian revolution qualifies as classically socialist (“the forced consolidation of the basic retail network constituted by Sears, Penneys, Safeway, and a few other chains,” Weston notes), but Ecotopia is more properly classified as a mixed economy, as a private market and currency backed by a central bank does still exist. But it’s clear that at its base, Ecotopia is an essentially syndicalist-socialist state, with self-determination regarding labor being its organizing principle. Small groups of people numbering in the few dozens spontaneously form communes, farms, factories, educational foundations, and research facilities based on their common interests and goals. In addition, work assignments change depending on need and demand; students spend more time in university trying out different occupations, and every Ecotopian inevitably ends up owing service to their society outside their own job. The nuclear family has been largely upended by the Ecotopian revolution, with Ecotopian children raised by their “village.” On the larger scale, Ecotopian living communities are smaller and more self-contained. Along with the nuclear family, the commuter suburb has been destroyed in favor of self-sufficient “ring towns” surrounding larger urban conurbations, all linked by low-pollution high-speed trains. These basic changes in living structures have, within a generation, altered the Ecotopian psyche deeply. There is a greater openness to experience and to emotion, a greater sense of the interconnectedness of all Ecotopians.