Feed aggregator

[Friday Fantasy] Down There

With Down There both author and publisher expand their range into a whole other genre, a whole other game system, and a whole other setting. Both Adam Gauntlett and Stygian Fox Publishing are best known for their ventures in Cosmic Horror and titles for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition and Trail of Cthulhu. Adam Gauntlett for titles such as The Man Downstairs and Stygian Fox Publishing for titles such as Things We leave Behind. With Down There, both author and publisher have released their first fantasy adventure, their first scenario for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, and their first scenario set in the Forgotten Realms.

With Down There both author and publisher expand their range into a whole other genre, a whole other game system, and a whole other setting. Both Adam Gauntlett and Stygian Fox Publishing are best known for their ventures in Cosmic Horror and titles for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition and Trail of Cthulhu. Adam Gauntlett for titles such as The Man Downstairs and Stygian Fox Publishing for titles such as Things We leave Behind. With Down There, both author and publisher have released their first fantasy adventure, their first scenario for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, and their first scenario set in the Forgotten Realms.Down There—subtitled ‘A Fight Against the Shadows of a Sunken Temple from the Award-Winning Maker of Horror RPG Adventures’—is set in Curgir in the northern vales of the Evermoors in north-west Faerûn, a village famous for its apples and its cider, but also for its strange past. The village was once the site of a great temple which was built following the defeat of a cult devoted to the Horned Devil Caarcrinolaas and subsequently swallowed up by the ground, never to be seen again. Inhabited by a mix of Humans, Halflings, and Half-Orcs, the land on which the village sits is owned Greystone Abbey, which has established a Chapter House in the village. The monks of the Chapter House collect rent, settle disputes, and maintain common land. More recently, the monks at the Chapter House have decided to re-establish the temple with the aim of this one not sinking into the ground like the last one. To that end, the head of the Chapter House hired Marin Chain-Breaker, a Dragonborn Exorcist to determine a means of preventing that—and now he has. He plans to hold a holy wedding on the land where the new temple will be, the ceremony aiding in the reconsecration of the ground. Designed for Player Characters of First to Fourth Level, Down There will see them encounter strange creatures of shadow, dark secrets of the past, and Halfling Monks who are not what they seem!

The Player Characters are hired by Marin Chain-Breaker to escort him to Curgir and help him in his plans to re-establish the temple and prevent its disappearance. The story kicks into action when they come across signs of an abduction on the path and a note that should have been taken to Greystone Abbey. It appears that of late, the villagers are upset about the Chapter House’s leadership of Curgir, but do not give specifics as to why. Once the Player Characters reach Curgir, they find its inhabitants slightly subdued, but they can learn more with a bit of gossip. All clues point to the Chapter House, and there the Player Characters will have the first of the scenario’s two confrontations with darkness and evil. The second will likely follow after—though the scenario’s two big encounters can be played in any order—and take place in the remains of the temple that was lost… There the Player Characters will battle for the souls of the bride and groom to be, and more!

Down There involves a good mix of investigation and interaction, as well as the two combative confrontations. It comes very well appointed, as you would expect for a scenario from Stygian fox Publishing. The artwork is excellent and the maps very clear, whether for the players or the Dungeon Master. It does need an edit in places, though. Unfortunately, that is a minor problem when compared to the difficulty that the Dungeon master might have in running Down There. The issue that the contents of the scenario are not very organised. Once past the short introduction, the reader is quickly into a list of rumours and clues relating to the mystery of what is going on in Curgir, followed by an explanation of what Marin Chain-Breaker wants, and then into the scenario itself. Down There simply does not take the time to explain to the reader and potential Dungeon Master what exactly is going on in the village before diving into the plot itself. The result is that Dungeon Master has to learn it fully as she reads and thus everything is at first a surprise followed by a greater effort to pull its various elements into something that she can run.

Despite the issue with the organisation, Down There is a more than serviceable scenario. It is well presented with good maps and nicely done NPCs. It neatly subverts both the jolly image of both the Halfling Race and the reserved characters of the Monk Class, together a default combination in Dungeons & Dragons since Dungeons & Dragons, Third Edition, and turns them into something greedy and venal. There is a strong streak of horror too, with some creepy moments, primarily involving the shadows which permeate the village. Whilst it needs more preparation than it really should, Down There is a good combination of the horror genre with the fantasy and would add a darker, slightly twisted feel to any Dungeons & Dragons setting, not just the Forgotten Realms.

“YES, WE’VE GOT A TWITCH CHANNEL!”

#AtoZChallenge2021: G is for Glaistig

Another creature from the stories and myths of Scotland. This time a creature that is either a faerie or a ghost. While the desire is there to classify everything, sometime the creature in question has many properties and game designers do the best they can. So today I am presenting the Glaistig; the Woman in Green or the Witch of the Wood.

Like the Banshee, the Glaistig is one of many different types of faerie women that might also be ghosts that inhabit the stories, myths, and legends of the British Isles. While the Banshee can be slotted, game-wise, as a ghost, the Glaistig makes more sense as a living faerie creature.

Woman in Green by Gary Dupuis

Woman in Green by Gary Dupuis

Glastig

aka Witch of the Wood, Green Lady

Medium Fey

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1)

Alignment: Neutral [Chaotic Neutral 75%, Chaotic Good 20%, Chaotic Evil 5%)

Movement: 120' (40') [12"]

Armor Class: 7 [12]

Hit Dice: 9d8+9** (50 hp)

THAC0: 12 (+7)

Attacks: 1 slam or spell

Damage: 1d6+2

Special: Witch spells, Fey qualities, become ethereal at will.

Save: Witch 9

Morale: 10 (10)

Treasure Hoard Class: None

XP: 2,300 (OSE) 2,400 (LL)

A glastig is a green-skinned woman with the legs of a donkey. She will often hide these in long dresses. Since she has the ability to become ethereal she is often thought of as a ghost.

She prefers not to attack physically but can do so by launching herself with her powerful legs to slam into a creature. Otherwise, she can cast spells as a Witch of the 7th level and make herself ethereal at will.

As a fey creature, she is immune to the effects of a ghoul's paralysis. Silver or magic weapons are required to hit. Cold iron weapons can be used and will do double damage.

The glastig protects her lands and area fiercely. She will attack invaders but can aid those that also protect her lands. Glastigs will work with other fey creatures to keep their lands safe. For this and her magic use, they are often called "the witch of the woods." They are also known as "The Green Lady" due to their skin color and the color they are favored to wear.

To appease a glastig it is common to leave a bit of milk in a bowl on a rock near where the glastig is believed to live. When no one can see the glastig will drink the milk and add whoever left it out to her circle of protection and be inclined to be Good towards them. If the milk is spoiled when left out the glastig will disfavor the humans and become Evil. Most times the glastig is neutral to humans.

--

She is a bit like a dryad and a bit like a nymph but a lot more powerful. This is not the first monster I have made that uses witch magic, nor will it be the last.

#AtoZChallenge2021: F is for Faun

My interest in RPGs and D&D, in particular, came from my love of Greek myths. I was already a fan of Greek myths when I first picked up a copy of the AD&D Monster Manual all the way back in 1979. So I could not in good conscious even think about bringing a new monster book to life if it did not somehow honor both my love for those old myths and that original book. So to that end, here is the Faun, a creature from Greek/Roman myths and related to the satyr of those myths and the Monster Manual.

Faun

Medium Fey

4d8+4* (22 hp) THAC0: 18 (+1) 15 (+4) Attacks: 1 weapon, song 1 weapon, song Damage: 1d6 1d6+1 Special: Song, fey qualities Song, fey qualities Save: Elf 1 Elf 4 Morale: 8 (8) 8 (10) Treasure Hoard Class: XVI (G) XVI (G) XP: 15 (OSE), 15 (LL) 200 (OSE), 215 (LL)

Fauns are fae people of the forest who love to entertain guests and go on dangerous quests. They can be rash and temperamental, and sometimes are reckless with the powers of their music. They are friendlier to men than most faeries, though are quickly angered by the destruction of woodland. Fauns, like satyrs, are the male counterparts to nymphs and dryads. When not playing music or drinking they are usually found chasing after nymphs. The offspring of a faun and nymph is a satyr if male and a nymph if female. As a creature of the fey, the faun is vulnerable to iron. They take double damage from any weapon made from cold iron. Additionally, they are immune to the effects of charm, sleep or hold spells unless they are cast by another fey creature of greater level/HD.

Fauns are the wilder cousins of the satyr. Like satyrs, they are rarely surprised (1 on a 1d8). Fauns all play musical instruments like pan pipes, flutes, or drums. If a faun plays everyone that hears must make a save vs. Spells or be affected by an Irresistible Dance spell. If the faun is with a mixed group of satyrs then their song of charm, fear, or sleep can also be in effect, with separate saves.

A faun will engage in combat to protect their lands, their fellow fauns, and nymphs or their herds of goats. Typically a faun is very much the stereotype of a lover and not a fighter. They can be bribed with wine, the stronger the better.

A faun appears to be much like a satyr. They are medium-sized with human-like broad hairy chests and muscular arms. Their lower half is that of a goat. Their faces are a combination of elf and goat with elongated faces, goat-like years and horns, and a beard.

Greater Faun: Greater Fauns are the larger and wilder varieties of fauns and satyrs. They are stronger and tougher than normal fauns and will act as leaders. Greater Fauns will claim descent from some god, typically Pan or some other primal nature diety.

Each greater faun has a True Name. Anyone that knows the True Name of a greater faun has power over him as per the spell Suggestion.

Some greater fauns are shamans and can also cast spells as a 2nd level druid.

--

So a tabled monster block today with two varieties. These are proper fae creatures so they have the vulnerability to iron.

Doing this table has pointed out some deficiencies in my approach though.

For starters, my Treasure Type/Horde Class needs some work. While XVI (G) makes sense to anyone that plays Labyrinth Lord and/or OSE, it is fairly inelegant. One, XVI or G would suffice. I guess I could just put the treasure types in the back of the book and work it out that way.

Secondly, and this is related to the same larger issue, my XP values are also a bit of an eyesore. Yes I am happy with the numbers I am getting. But while OSE and LL are covered this does nothing for the GM using say Swords &Wizardry or AD&D. I could just leave it blank, but XP listings are one of the really great things about later books and editions of the game.

Likely there will be a table in the back of the book with all the monsters listed with their XP values for various systems. That makes the most sense. But likely I will leave at least one there.

Contest: Win a Unique Triffid Ranch Enclosure For Your Workplace!

#AtoZChallenge2021: E is for Elf, Shadow

Back in September, I did a Shadow Week where I looked at various types of Shadow Elves for the various editions of the game. I mentioned then I had my own in the works. Well, it took me a bit, but here they are. Meet the Shadow Elves. Masters of their arts, but their art can kill you.

Elf, Shadow

Elf, Shadowaka Umbral Elf

Medium Humanoid (Fey)

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1d8 (2d8)

Alignment: Neutral [Chaotic Neutral]

Movement: 120' (40') [12"]

Armor Class: 8 [11]

Hit Dice: 1d8+1* (6 hp)

THAC0: 18 (+1)

Attacks: 1 weapon or special

Damage: 1d6

Special: See below; Fear immunity

Save: Elf 1

Morale: 8 (10)

Treasure Hoard Class: XX (C)

XP: 19 (OSE) 21 (LL)

Shadow Elves trace their ancestry back to the sundering of the elves and the elvish diaspora. Where some elves fled to the forests of the mortal world, some to deep underground, and others back to their ancestral lands in Faerie, these elves fled to the in-between planes of shadow. Here they changed and became something different than their kin. Like the Ranagwith or "Free Elves" they are rarely encountered.

The Umbral Elves as they are also known are tall, 6 to 6 1/2 feet tall, but thin, weighing only 150 lbs. Their skin is pale white to pale blues. Their hair varies from white to pale blonds to dark blacks. Redheads are rare and are taken as a great omen of change. They speak Elven and any other languages their intelligence scores allow. Due to their life living in the shadowy planes the shadow elf can also see the spirits of the dead and can speak to them (per the Speak to Dead spell). Shadow elves have infravision to 90' and low light vision to 120'. They are not unduly affected by sunlight as the dark elves are but they still do not prefer it. Umbral elves are not just immune to the touch of ghouls they are also immune to the touch of ghasts as well.

These elves are like other elves in that they produce great art, but their art, songs, and poems are all of a melancholic sort. It is said that listing to a Shadow Elf aria can move one to tears. Listing to an opera can move one to suicide. Suicides among shadow elf opera singers are so widespread it has become part of their cultural history. After a perfect performance, knowing they can never achieve more the singer will end their life. Likewise, all their art is breathtakingly beautiful but heartbroken. This has had an effect on the shadow elves as a people. They are completely immune to all fear. Even magical fear, such as from dragons or various fiends, has the effect of angering shadow elves. A failed save on any fear effect only causes them to pause for around. Then they react with anger.

Shadow elves do not have clerics. They feel the gods have forsaken them so they no longer offer them worship or devotion. They do have witches and warlocks that have patrons of primal forces, as well as wizards. For every group of 8 or more shadow elves, one will be a wizard or warlock of the 2nd level. For every group of 12 or more, there will be a wizard or warlock of 3rd level or higher. Shadow elves can take any class elves can save for cleric or paladin. Shadow elves find the "light" elves too frivolous and the "dark" elves too brutal. They do get along well enough with the Ranagwithe (Free Elves) as they see them as fellow outsiders.

Shadow elves, like all elves, are excellent archers, but most prefer not to use missile attacks if they can avoid it. Shadow elves have strict rules of honorable combat. They use specially designed short swords that they dedicate their lives to mastering. The shadow elf warrior prefers hand-to-hand combat. He considers combat to be the highest form of his art and his opponent should not be considered his enemy but something more akin to a dancing partner. Combat without a combatant is only practice. To this end, despite their chaotic alignments, the shadow elf will fight with honor. For example, if their opponent drops or breaks their weapon they will wait till they gain a new one. If they are fighting with a shield and their opponent does not have one the shadow elf will drop their shield as well. Older (higher level) shadow elves will be covered with scars from practice and previous battles. Shadow elves have even been known to weep openly at the death of a particularly powerful combatant; knowing in the pursuit of their own "art" they have destroyed another "artist."

Shadow Elves are found living in underground lairs, particularly dense and dark forests, and in the lands that overlap the Faerie World, the mortal world, and the shadow worlds.

--

Elves are as ubiquitous to the game as dragons are. I wanted an elf that was not something we have seen before. These are not the light elves of Tolkien or the dark elves of myth or even the Drow of Gygax or Salvatore. But they are not the Shadow Elves of Mystara either.

Elves in D&D are immune to the touch of ghouls. Shadow Elves, because part of their origin is the Plane of Shadow, extend that to Ghasts as well.

Since they are elves and not faerie creatures proper their type is Humanoid (Fey). They have some fey properties, but not all. For example, there are no hospitality codes for these creatures and they can handle iron with no issues.

Tomorrow I'll post a proper Fey creature, or maybe two!

New Triffid Ranch Events – April 2021

The Aftermath: Frightmare Collectibles Spring Slasher Camp 2021

#AtoZChallenge2021: D is for Dragon, Purple

I am SO glad I watched Dragonslayer over the weekend because it really puts me in the mood for today's monster.

Dragons are a huge part of the games we play at home. My oldest son LOVES dragons and has, well, I have no idea how many, scattered all over the place. His games are filled with dragons. So when I want to add new dragons to my games or books, I first turn to him. Especially if I want a fresh take.

I remember the Purple, Yellow, and Orange dragons from Dragon Magazine 65 and then updated in Dragon magazine 248. I included my own take on an Orange dragon in my Pumpkin Spice Witch book. This dragon was originally conceived for my High Witchcraft book. This is the dragon that has given us so many draconic bloodline sorcerers.

Dragon, Purple

Dragon, Purpleaka Draco Arcanis Occultis, Arcane Dragon

Huge Dragon

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1)

Alignment: Chaotic [Neutral Evil]

Movement: 180' (60') [18"]

Fly: 240' (80') [24"]

Burrow: 90' (30') [9"]

Armor Class: 0 [19]

Hit Dice: 10d8+20* (65 hp)

Huge: 10d12+20** (85 hp)

THAC0: 11 (+8)

Attacks: 2 claws, 1 bite, + special

Damage: 1d6+3x2, 2d8+3

Special: Breath weapon (magical energy), dragon fear, low-light vision (120’), magic use

Save: Monster 10

Morale: 10 (10)

Treasure Hoard Class: XV (H)

XP: 2,300 (OSE) 2,400 (LL)

Habitat: Underground or Urban areas

Probability Asleep: 25%

Probability of Speech: 100%

Breath Weapon: 75’ long, 5' wide beam of magical energy

Spells: First: 3, Second: 3, Third: 3, Fouth: 2, Fifth: 1

Purple dragons are a very rare mutation among prismatic dragons. They are born mostly to red, blue, or black dragons and rarely among green or white. Even then only 5% of all dragon births can result in a purple dragon. It is believed they are born most often in areas of high magic. Since all of the prismatic dragons are very vain, the wyrmling purple is often abandoned. Green dragons usually kill them outright. The ones that survive learn that their most important weapon is guile, trickery, and deceit.

Like all dragons, the purple can fight with its claws and bite. Their breath weapon is a 75' long beam of magical energy. They will also fight with spells in any form.

The purple dragons are among the smartest of all dragon-kind. They will always speak and use magic. They can cast spells as a magic-user/wizard of 9th level. These dragons are fond of casting Polymorph Self (fourth level) and masquerading as a human. In this form, they will be found living in cities where they will often study magic and accumulate wealth. Their lairs will have an underground area where they will keep their treasures and sleep in their dragon form.

These dragons are very solitary in regards to other dragons, but they do keep humanoids nearby. These are often servants, slaves, thralls, and the occasional victim. They have been known to also become the patrons of Draconic Warlocks and Witches. Wizards will also seek them out for advanced training in the magical arts. A purple dragon can speak draconic, common, its alignment language, and up to four more languages. Typically elven is learned.

--

This block has the extra details needed for dragons. Additionally, we see our first Huge creature. It can use the normal d8 for hp if you wish to stick to the rules of your particular Basic game, or you can use a d12 instead to reflect its larger size. In the case of this 10 HD monster, the difference is 20 hp.

AND

If you are doing the A to Z Challenge Scavenger Hunt, you just found a Dragon!

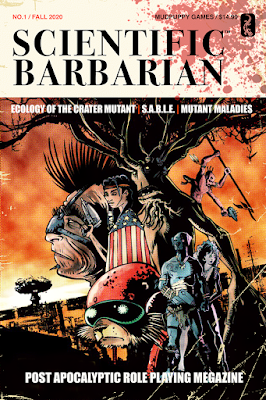

[Fanzine Focus XXIII] Scientific Barbarian #1

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will be compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry. However, fantasy is not the only genre to be explored in the pages of the fanzine renaissance.

Just as a number of fanzines have appeared to support Goodman Games’ Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game, such as Crawl!, a number have also appeared to support Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic and the Post-Apocalypse genre. For example, Bunker, Gamma Zine, and Meandering. The latest is Scientific Barbarian, its content written for use with the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game and published by Mudpuppy Games. Edited by Jim Wampler, designer of the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, its contents can of course, be adapted to other Post-Apocalypse roleplaying games.

Scientific Barbarian #1 was published in the autumn of 2020 following a successful Kickstarter campaign. As you would expect, it comes full of robots, mutations and maladies, and monsters aplenty, as well as a sizable techno-dungeon. With its excellent cover aping the look of Scientific American, Scientific Barbarian #1 is cleanly laid out, illustrated with a range of decent artwork, and is an easy read. It opens with ‘Bunker Briefings’, an editorial in which Wampler sets out his stall, stating that the fanzine is designed to support the ‘Mutant Murder Hobo’ style of play and welcomes those who have come across the fantasy genre to this one. The latter theme is continued with ‘Apocalyptic Visions – It’s Okay to have 87 Eyes’, in which Tim Kask extolls the virtues of mutations in Post-Apocalypse roleplaying games, particularly the joy of playing and roleplaying defects.

The contents get a proper start with Levi Combs’ ‘Ecology of the Crater Mutant’. This describes the barbarous, hardy mutants who worship and are mutated by a great source of radiation located at the heart of the crater where they live. Their faith in The Gospel of the Glow drives them to kidnap others and expose them to the radiation and so transform them into members of the ‘family’. The Crater Mutants are cross between Orcs and hillbillies and definitely support the ‘Mutant Murder Hobo’ style of play. It does feel overwritten, as if it could have been shorter, but that tends to be the way of such ecology articles. It is followed by ‘S.A.B.L.E. Rangers – Security Automations for Basic Law Enforcement’ by Michael Stewart and Elizabeth Stewart which details a law enforcement initiative begun in the ‘before times’ of the thirtieth century, aiming to combine the impartial judgement of A.I. law enforcement with the moral oversight of a human partner, thus mitigating human prejudices and sympathies. The programme developer, Automates, Inc., built several prototypes before the Great Disaster which buried its manufacturing complexes. Recent tectonic shifting has exposed the complexes, allowing the prototypes, each in the friendly form of a robotic horse, to escape and begin their duties as law enforcement devices. A S.A.B.L.E. Ranger unit—of which three types are detailed in the article—might already be found with a partner sitting astride it, but the obvious option and the one explored more fully is ‘A Sentient and the Horse’, in which the robot teams up with a Player Character. In addition to the obvious nod to A Dog and his Boy, the article nicely explores the idea and sets up great roleplaying potential between the Player Character and the S.A.B.L.E. Ranger unit, effectively giving the Judge a Player Character of her own to play. This would lend itself to play with just the Judge and a single player, but it could also work with another player roleplaying the S.A.B.L.E. Ranger unit too, although that is not supported in the article. Which is a pity as it is a missed opportunity. There is a Saturday morning cartoon and very American Wild West feel to the article, but otherwise an engaging piece.

‘Mutant Maladies’ by Skeeter Green is a preview of a forthcoming supplement of the same name which adds diseases and contagions to the Post Apocalypse. It gives stats and effects for several diseases, including AMD-6 or ‘Marrowblight’, which hardens the bone marrow of Pure Strain Humans, or Ultra-Coagulation or ‘Thickblood’, which turns the liquid blood of its sufferers into goop. The three diseases are described in some detail, but whilst their utility is obvious, it may be limited, since the Judge may not want to expose her Player Characters to such maladies too often, since their debilitating effects may impede game play. This is not to say that the diseases are not well designed or that the article is not decently written, but of limited scope. More useful then, is ‘Glowing Good Looks’ by James M. Ward, the designer of both Metamorphosis Alpha and Gamma World, which presents a set of three tables to be rolled on whenever a saving throw versus radiation is missed or fumbled. There are tables for humanoids, winged-folk, and four-legged mutants, all of which provide minor mutations. As promised, these are quick and easy, and sufficiently utilitarian that they work with any post-apocalyptic roleplaying game.

Pride of place in Scientific Barbarian #1 goes to Jim Wampler’s ‘The Gene Looms of Janeck-Vac’. Designed for Player Characters of Fourth and Fifth Levels, this scenario has a traditional set-up—a village suddenly imperilled by a rash of strange creatures with new mutations appearing from the nearby jungles and the Player Characters ordered by the tribal elders to investigate and put a stop to it. After a few encounters in the jungle with these strange creatures—swarms of Batslugs, Spiderhogs, and Cobrapedes—they come upon a caldera and below that a facility of the ancients full of strange devices the interfering of which will have unfathomable consequences for the Player Characters, but then again, they are Player Characters and this is the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, so of course they will interfere. As the title of the scenario suggests, the underground complex is a genetics laboratory, and if they are careful, there are lots of secrets to be discovered and even the real Janeck-Vac to be encountered. If they are really lucky, there are some singular artefacts of the Ancients which would make fine additions to the Player Characters’ equipment and provide some excellent roleplaying opportunities into the bargain. As well as a decent set of floorplans for the facility, the scenario is accompanied by stats and write-ups for all eight of the weird mutant strains that the genetics laboratory has released to date, which of course, could appear elsewhere in the Omega-Terra of the Judge’s own campaign. The structure of the scenario does feel familiar, having been seen in multiple scenarios for Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game and other Post-Apocalypse roleplaying games before, but it is nicely detailed and adds a twist or two on the threat from the past coming back to haunt the future.

The monsters found in ‘The Gene Looms of Janeck-Vac’ are not the only ones to be found in Scientific Barbarian #1. ‘Creature Cryptology’ provides a half dozen new creatures which the Judge can include in her campaign. Some, like the ‘Eye-Cap’ is a weird variation upon a Dungeons & Dragons-style monster, the occasionally mobile, sentient fungus covered in chitinous plates and eyestalks which grant it 360° vision and which can launch a cloud of tiny flying eye spores each capable of firing an infrared laser beam! This is a nasty creature whose main means of attack can only be targeted by area effect attacks. Others are particular to the genre and the setting, such as the ‘Gem Thief’, a holographic data crystal which attempts to mind control its current possessor and subtly directs him to where others of its kind might be found. In fact, each ‘Gem Thief’ once belonged to a lost A.I. deity and seeks to find others of its kind to resurrect the A.I. deity. The nature and identity of the lost A.I. deity is left up to the Judge to decide. Overall, the selection to be found in ‘Creature Cryptology’ is variable in terms of quality or usefulness, but that is the nature of the fanzine, plus the Judge can easily adjust any one of the new creatures in the issue.

Rounding out Scientific Barbarian #1 is a ‘Retro-Review’ of Jack Kirby’s Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth. Written by Scott Robinson, the review focusses mainly on the reviewer’s personal reaction to the collected omnibus—now and original issues when he was thirteen years old. The result is oddly uninformative and so not all that helpful to the reader when determining his interest in Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth. This could have been addressed by the editor as well. The review is followed by a pair of cartoon strips, one an excerpt from the comic strip, Knights of the Dinner Table, the other entitled ‘Onto the Wasteland…’ Together they bring the first issue of Scientific Barbarian #1 to an entertaining close.

Scientific Barbarian #1 is something of a curate’s egg—partly bad and partly good. Or rather partly merely adequate and partly good. There are perhaps a few too many monsters in the issue, what with monsters in both the scenario and their department, the review could have been much tighter, and other articles shorter. Oddly, for a fanzine dedicated to Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, there is a lack of new technology described in its pages. However, the table of new mutations is efficient and useful, the write-up and development of the S.A.B.L.E. Ranger unit concept is nicely done, and of course, ‘The Gene Looms of Janeck-Vac’ is a decent scenario with some hidden depths to it. Overall, the good definitely outweighs the not so good and just like the magazine it pastiches, Scientific Barbarian #1 is the first issue of fanzine which should be worth subscribing to, whatever Post-Apocalypse roleplaying game you already have a subscription for.

[Fanzine Focus XXIII] Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs

On the tail of Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another Dungeon Master and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry.

On the tail of Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another Dungeon Master and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry.Echoes From Fomalhaut is a fanzine of a different stripe. Published and edited by Gabor Lux, it is a Hungarian fanzine which focuses on ‘Advanced’ fantasy roleplaying games, such as Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and Advanced Labyrinth. The inaugural issue, Echoes From Fomalhaut #01: Beware the Beekeeper!, published in March, 2018, presented a solid mix of dungeons, adventures, and various articles designed to present ‘good vanilla’, that is, standard fantasy, but with a heart. Published in August, 2018, the second issue, Echoes From Fomalhaut #02: Gont, Nest of Spies continued this trend with content mostly drawn from the publisher’s own campaign, but as decent as its content was, really needed more of a hook to pull reader and potential Dungeon Master into the issue and the players and their characters into the content. Echoes From Fomalhaut #03: Blood, Death, and Tourism was published in September, 2018 and in reducing the number of articles it gave the fanzine more of a focus and allowed more of the feel of the publisher’s ‘City of Vultures’ campaign to shine through.

Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs continues this focus and again keeps the article count down to just four. Published in January, 2019, the issue opens with ‘The Technological Table’, a list of futuristic weapons and gadgets, ranging from laser pistol and laser spear to the God-box and The Dark Eye. Many of these items will be familiar from Science Fiction and other gaming articles, so it is refreshing to see some interesting entries alongside the usual electro-whip and laser sword. For example, Aquastel is a liquid so weighty, that when mixed with other liquids, it separates their constituent parts into layers according to their density, so could be used to neutralise poisons or extract valuable metals. The God-box is a communications link to an information bank located deep underground which can be consulted for information, though it is likely to be out of date or phrased on language that the Player Characters do not understand. This sort of article supports a setting where the campaign planet has links to a star faring civilisation or the various weapons and gadgets are remnants of a prior civilisation, fallen long ago. There are echoes of the lost civilisation set-up in the scenario, ‘Terror on Tridentfish Island’, published in Echoes From Fomalhaut #03: Blood, Death, and Tourism.

The scenario in Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs is the eponymous ‘Revenge of the Frogs’. The has always been an element of batrachian horror in Dungeons & Dragons, going back to Dave Arneson’s scenario, ‘Temple of the Frog’ and creatures such as the Bullywug, as well as drawing on H.P. Lovecraft’s short story, ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth’. Frogs can be alien and emotionless creatures, so make a weird, but worthy enemy in any Dungeons & Dragons scenario. Designed for Player Characters of Third to Fifth Levels, ‘Revenge of the Frogs’ maroons them in the mouldering port of Silvash. The winds have ceased and the local high-priest of Murtar, God of Murky Waters hires the Player Characters to locate the means to restore them in the nearby marshland and prevent the rising of a frog-cult and its dread god that in ages past was destroyed by the priesthood of Murtar. The scenario is designed as a sandbox which will see the Player Characters delving deeper and deeper into the marshland, encountering various dank dangers and independently-minded inhabitants, all of whom are nicely fleshed out and bring colour to the region. Originally written as a companion piece to ‘Cloister of the Frog God’, part of Frog God Games’ Rappan Athuk megadungeon, Revenge of the Frogs’ is a bit rough around the edges and underwritten in terms of set-up and its explanation, especially in the placement of one of its magical items needed to complete the scenario. Otherwise, the scenario has a Lovecraftian tinge combined with a pleasing sense of mouldering decay.

Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs comes with a map which depicts the outline of a city. This of ‘Arfel – City State of the Charnel God’, which is fully detailed in the issue of the fanzine. This is a city dominated by Ozolba the Zombie God from his labyrinth temple-complex and necropolis which overlooks the city. He and his priesthood—both undead and living—can claim what they want and who they want, and to object is a sin. The nobility of Arfel abide by the stifling Necrotic Traditions, rarely if ever leaving their mansions which are perpetually shrouded in mourning, giving parts of Arfel a sepulchral feel. In the absence of civil government, crime syndicates and gangs have stepped in to run the city, though only unofficially. Only the Outer City beyond its walls is free from Ozolba the Zombie God’s reach, though it a lawless, rough place, where protection much be bought. Meanwhile, throughout the city can be found cat after cat after cat, which hunt in packs against the cat-catchers of the Outer City and know its secret ways from one end to the other. Again, there is the sense of the Lovecraftian to Arfel, it having a Dreamlands-like feel, though heavily influenced by Clark Ashton Smith’s Mordiggian, the Charnel God.

As with Echoes From Fomalhaut #03: Blood, Death, and Tourism, the remaining half of Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs is dedicated to one article. In the previous issue, this was ‘Erillion, East’, in this issue it is ‘Erillion, West’. This is the second half of a gazetteer detailing the island of Erillion, previously described in Echoes From Fomalhaut #02 and for the most part completed here—there are still plenty of locations mentioned here to be fully detailed in future issues. It continues to detail numerous locations and aspects of this end of the island, some forty or more of them. There is a strand of religiosity which runs through the location descriptions, notably the ‘Lunar Path’, a pilgrimage which leads from black lunar stones to black lunar stones and which will grant those successful with access to the world of dreams, but test them mightily in the process, and the ‘Isle of Trials’, an island west of Erillion, but connected by a pirate infested bridge, which is home to numerous persecuted cults and religious movements. Here the thumbnail descriptions never get as far as living up to their promise, since the reader is left wondering more about the cult or the religious movement and what their religious beliefs are. Hopefully, these might be detailed in a future issue. Otherwise, the thumbnail descriptions are decently done, such as the band of Ogre bandits which capture children and fatten them up for the pot, the court of Lord Virguard the Besieger who keeps five chairs empty in memory of his lost adventuring companions and who will reward tales of brave adventuring, and a marble chess high in the mountains, where two legendary wizards, one transformed into a mountain, the other a cloud, play out an endless game with living figures for the Staff of Power. There are also lots of bandits and thieves and berserkers to encounter too. This western half of Erillion is even more lawless than the Eastern half, and like the earlier ‘Erillion, East’, this half consists of many locations that might be passed through or discovered rather than necessarily visited with any purpose and the Dungeon Master will want to create that purpose or use the scenarios published in the earlier issues which are set on the island.

Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs definitely feels all the better for having just four articles, their content being allowed to breath and not feel crammed in. It is lightly illustrated, but much of the artwork is really quite good, whether it is public domain or commissioned for the issue, it all fits the oppressive ‘Mitteleuropa’ feel of the author’s ‘City of Vultures’ campaign and is well chosen. It needs an edit here and there, but is generally well written. Of the content, ‘The Technological Table’ is the outlier. It is a good article, but it feels out of place with the rest of the content, whilst the enjoyable ‘Revenge of the Frogs’, creepy ‘Arfel – City State of the Charnel God’, and completing overview that is ‘Erillion, West’, all feel as if they are in the same world. And that perhaps is a problem too, because so far Echoes From Fomalhaut is only giving us snapshots of the ‘City of Vultures’ campaign, not quite a partwork, but getting there. Overall, Echoes From Fomalhaut #04: Revenge of the Frogs is sol'd issue of the fanzine, but it is beginning to feel as if something is wanted to begin pulling the ‘City of Vultures’ campaign together.

Sword & Sorcery & Cinema: Dragonslayer (1981)

Since April is Monster Month here I thought it might be fun to check some monster-themed Sword & Sorcery & Cinema movies. Up first is a classic and premiered at the height of the 80s fantasy craze. Here is 1981's Dragonslayer from both Paramount and Disney.

Since April is Monster Month here I thought it might be fun to check some monster-themed Sword & Sorcery & Cinema movies. Up first is a classic and premiered at the height of the 80s fantasy craze. Here is 1981's Dragonslayer from both Paramount and Disney.We are introduced to one of the most famous dragons outside of Westeros or Erebor, Vermithrax Pejorative. Though he is mentioned among the dragons in Game of Throne's first season.

The movie is a little slow, but on par with what was normal at the time. Peter MacNicol is fine as the apprentice turned dragonslayer Galen, but I can't help but think if someone else would have been better in the role. Caitlin Clarke was great as the girl pretending to be a boy Valerian. She returned to theatre work after this and this was her only major role. She sadly passed of ovarian cancer in 2004.

Sadly the movie under-performed in the box office and some of the reviews were not great, but the movie was fun then and to be honest the effects have held up well enough. It has achieved "cult movie" status and that is not a bad thing. It certainly is a great one to have on a Dragon-themed movie night.

The effects are good and the director gets away with a lot of "showing less is more." We only see bits and pieces of the dragon until the very end when it is most effective. Sure some of the stop motion looks very stop motion-y, but Vermithrax still looks like he could go toe to toe with Smaug or Drogon. I really can't help but think that this dragon wasn't at least some of the inspiration for the DragonRaid game.

The musical queues in this are pure Disney so they are also very effective.

Gaming Content

Now THAT is a Dragonlance! The Sicarius Dracorum really shows that a spear, or a lance, is the best weapon for fighting a dragon. The forging scene where Galen heats the metal with magic is really one of the best. If you are not forging your magic weapons like this then you are missing out!

Caitlin's dragon scale shield, while less theatric, is just as magical.

I am sure there are those that will nitpick that the "dragon" only has two legs and not four, but I can't get worked up over that. He is still a fantastic dragon.

#AtoZChallenge2021: C is for Cat-sìth

Another creature in the guise of an animal and we do not go too far astray from the homes of the barghest. This time the animal is a cat and creature is a Cat-sìth.

Cat-sìth

Cat-sìthaka Cait Sídhe

Medium Fey

Frequency: Rare

Number Appearing: 1 (1d8)

Alignment: Neutral [Chaotic Neutral]

Movement: 180' (60') [18"]

Armor Class: 3 [16]

Hit Dice: 4d8+4* (22 hp)

THAC0: 15 (+4)

Attacks: 2 claws, 1 bite, + special

Damage: 1d4+1 x2, 1d6+1

Special: Bad luck, fear, low-light vision (120’), scent, speech

Save: Monster 4

Morale: 6 (6)

Treasure Hoard Class: None

XP: 200 (OSE) 215 (LL)

Cait Sídhe or Cat Sìth (Caught SHEE) are magical cat-like creatures that populate the same lands of faeries and other woodland creatures. They appear to be large cats with black fur and a spot of white on their chest. Sometimes they have white paws or even white faces. All cat-sìth have eyes that glow yellow, orange, or green. In the lands they call home the cat-sìth are often feared to be demons or a witch in the form of a cat. In any case, the appearance of a cat sìth is a sure sign that a witch is nearby.

Cat-sìth makes sudden sprints to bring down prey. It prefers to attack small mammals and birds and rarely physically attack humanoids, though it has been recorded of a Cat-sìth adding a pixie or brownie to their diet once in a while. When dealing with humanoids a cat-sìth can defend themselves physically but prefer to use their spell-like abilities.

Bad Luck: The cat-sìth can target one victim as a recipient of a Bad Luck curse. This cast as a Bestow Curse spell by a 4th level witch. The victim is at a -2 on all rolls till sunrise the next day. The cat-sìth may do this up to 3/day but multiple uses on the same target are not cumulative.

Fear: The sight of a cat-sìth is so disturbing to most that it emanates a Fear Aura that acts like a fear spell cast by a 5th level caster. The difference is that the aura is limited to 5’ and the victim must be able to see the cat sìth.

The cat-sìth has low-light vision to 120’. A cat-sìth is capable of speech and can speak any language its intelligence allows. They can speak Common, Sylvan, any local language, and the language of Cats.

The cat-sìth makes an excellent familiar. Their association with witches is long and not without cause. Most cat-sìth avoid humanoids, with the exceptions of the fey, so the only ones likely to be encountered by humanoids are the ones in the charge of a witch. They are all believed to be in the service of the King of Cats (Cat Lord).

--

A fun little beastie. This one adds an "AKA" line under the name, many monsters are known by other names as well.

While this one looks like a cat it is actually a faerie creature. Now I could have listed it as Beast (Fey) like the Barghest is Beast (Demonic), but I felt that it fit better as a proper creature of the fey.

[Fanzine Focus XXIII] Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will be compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry.

Delayed Blast Gamemaster is a fanzine of a different stripe. Published by Philip Reed Games following successful Kickstarter campaigns, Delayed Blast Gamemaster is a fanzine dedicated to supporting roleplaying fantasy games, but a particular style of fantasy roleplaying games—Dungeons & Dragons. Yet the issues are entirely systemless, which means that their contents can be used in Dungeons & Dragons, any of the fantasy roleplaying retroclones you care to name, and most fantasy roleplaying games with a little effort. Published following a successful Kickstarter campaign as part of the inaugural Zine Quest, the first issue of Delayed Blast Gamemaster was published in September, 2019, followed by the second issue a year later in September, 2020, again following a successful Kickstarter campaign.

Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2 is as physically striking as Delayed Blast Gamemaster #1. Its graphical design is all white art and text on matt black pages (a printer friendly version is also available), the effect being striking, almost jauntily creepy and oppressive in its artwork’s depiction of mad mages, wiggle cubes, undying angers, gnashing rock beasts, and more. Again, the text is both heavy and large, so is a lot easier to read than it otherwise might have been.

As to the concept behind Delayed Blast Gamemaster it is simply that of inspiration scattered subject by subject across nine tables. So ‘OneDTen Urban Locations’, ‘OneDSix Forgotten Spellbooks’, ‘FiveDSix Unusual Treasures’, ‘OneDEight Dungeon Oddities’, ‘OneDSix Magic Shields’, ‘TwoDSix Potions’, ‘OneDSix Warped Monsters’, ‘OneDTwelve Adventure Hooks’, and ‘OneDFour Dungeon Doors’. So all that the Game Master has to do is pick a table or subject, roll the die, check the relevant entry, and use it as inspiration to create something of her or adapt the entry to the roleplaying game of her choice. The most obvious choice to adapt the entry to, is of course, Dungeons & Dragons, due to the similarities in language, but other roleplaying games would work too.

The concept behind Delayed Blast Gamemaster and thus Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2 is tables of inspiration accompanied by more tables. There are eleven such tables in the issue, ranging from ‘OneDSix Dungeon Characters’ and ‘FiveDSix Unusual Treasures’ to ‘OneDEight Dungeon Conditions’ and ‘OneDSix Pockets Picked’. Thus, all that the Game Master has to do is pick a table or subject, roll the die, check the relevant entry, and use it as inspiration to create something of her or adapt the entry to the roleplaying game of her choice. The most obvious choice to adapt the entry to, is of course, Dungeons & Dragons, due to the similarities in terminology, but other roleplaying games would work too.

For example, roll a five on ‘OneDEight Adventure Hooks’ and the Game Master has her adventurers encounter a ‘Grizzled Warrior Questioning His Career’. The veteran, the worse for wear from drink readily shares tales of his exploits, the type of exploits that the Player Characters are likely going to want to emulate, though somewhat ruefully since he seems to regret his career choice. However, his ramblings might contain a nugget of truth or two, necessitating a further roll of a four-sided die. For example, a roll of a three determines that he regales the party of the time that he and his companions were attacked by a giant whose mighty Warhammer crushed many of them, and the last time he saw the giant, it was wandering away with the possessions of those he had slaughtered. Could the giant still have their possessions, and just were they?

Alternatively, roll a fourteen on ‘FiveDSix Unwanted Treasures’—a sequel to ‘FiveDSix Unusual Treasures’ from Delayed Blast Gamemaster #1—and the adventurers find a small book bound in metal with pages of thick parchment, half full with the incomplete memoirs of a halfling merchant which tell of his life as a great lover and warrior. Similarly, ‘OneDEight Dungeon Oddities’ is another sequel to a table from Delayed Blast Gamemaster #1. It provides more monstrous encounters, such as the ‘Wizard’s Goblinoid’, a result of a roll of one on the table, which describes a goblin who really, weirdly enjoys being a Wizard’s familiar and knows a few cantrips, whilst a roll of five would give a ‘Wiggle Cube’, a very rare orange gelatinous cuboid with sufficient awareness to track down and take control of other oozes and slimes. Perhaps one of the most engaging table is ‘OneDSix Guards’, which describes the personalities of six town guards so making them more than just the local watch ready to step in when the party causes trouble!

With eleven tables, there are a lot of entries and ideas in Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2, which is the point. In comparison to the first issue, there is a better range of entries in Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2, including oddities, memorable weapons, adventure hooks, magic scrolls, dungeon conditions, and the contents of pockets picked. There are, however, a few tables and entries which are designed for single use only given their suggested rarity. The ‘Wiggle Cube’ from ‘OneDEight Dungeon Oddities’ is one such entry, whilst the ‘OneDSix Goblins’ table gives six strange, even singular goblins that it is advised that the Dungeon Master consult the table rarely lest their overuse lessen their impact. This slightly reduces the utility of Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2.

Rounding out Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2 is ‘Cave of Eyes’, a six-location set of caverns which comes with a background and some broad detail such that it needs to be fleshed out and detailed by the Dungeon Master. It is not a particularly interesting location as written and really needs that input, and perhaps it might have been more interesting if it had included suggestions as to which tables the Dungeon Master could roll on to further develop the cave complex. Otherwise, a table might have been more useful.

Once again, Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2 presents a plethora of things a Game Master can bring to her game. She will need to do some work to bring them into her campaign, but the ideas will work with Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition as much as they would with Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy, Dungeon Crawl Classics, or The Fantasy Trip. Whatever your choice of fantasy roleplaying game, further inspiration is never unwanted and Delayed Blast Gamemaster #2 yet more.

Have a Safe Weekend

#AtoZChallenge2021: B is for Barghest

Here is an old favorite of mine that I have done a couple of different versions of in various postings and books. Is this the final version? No idea! But it is getting close.

This one is a nasty little beastie from English lore.

Barghest

Large Beast (Demonic)

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 1d6 (1 or 1d4)

Alignment: Chaotic [Chaotic Evil]

Movement: 180' (60') [18"]

Humanoid: 120' (40') [12"]

Hybrid: 150' (50') [15"]

Armor Class: 3 [16]

Hit Dice: 6d8+12** (39 hp)

Large 6d10+12** (45 hp)

THAC0: 13 (+6)

Attacks: 2 claws (humanoid/hybrid) or 1 bite (dog/hybrid)

Damage: 1d6 x2 claw or 2d4 bite

Special: Stare, hit by silver or magical weapons.

Save: Monster 6

Morale: 10 (10)

Treasure Hoard Class: None

XP: 950 (OSE) 980 (LL)

A Barghest is an evil shape-changing fiend that hungers for the souls of mortals. A barghest may appear as a huge demonic black dog the size of a bear, or in a humanoid form nearly seven feet tall, resembling a goblin or wingless gargoyle, or a combination of both forms. A barghest never uses weapons, even in its humanoid form, preferring to feel the blood of its enemies run down its claws. It is tenacious; if a barghest fails its morale check and flees, it will return in 1d6 turns to attack again.

Anyone who meets the gaze of a barghest will feel the heat of the monster's stare; such characters must save vs. Paralysis or be paralyzed in terror for 1d6+1 turns (or until the barghest is slain). A character is deemed to have met the gaze of the barghest if he or she faces it in combat, or if the character is surprised by the monster. Fighting a barghest with gaze averted results in a penalty of -4 on all attack rolls. Those who succeed at the saving throw are immune to the monster's gaze for the remainder of the combat (at least one full turn at the minimum).

Although it is not undead, a barghest is inherently unholy and can be Turned by Clerics (as a spectre). They can only be harmed by silver or magical weapons. A barghest generally speaks Common as well as the languages of infernals, goblins, hobgoblins, and bugbears, and can communicate with wolves. One can sometimes be found ruling over goblins or hobgoblins, but most commonly a barghest haunts a lonely stretch of road, preying on travelers.

Barghest lairs will only have a single creature or a creature and up to three whelps. A barghest whelm is weaned at one year and kicked out of the lair. If encountered by a parent or siblings it will be attacked. Barghests have no sense of family and hate all creatures except for themselves.

Their coats are of the darkest of blacks and often matted with blood. Their eyes burn red and it is said the fires of hell can be seen in them.

--

What's new today?

This creature has a few more things going on.

First, it is a Large Beast (Demonic). Let's break that down.

In my Basic Bestiary, I am going to give different HD for different sized creatures. A Large creature will use a d10. Medium creatures will still use a standard d8, Small a d6, and Tiny a d4. On the other side of things, a Huge creature will use a d12 and a Gargantuan creature will use a d20. This is much the same as D&D 5e uses.

For the purists, you can continue to use the d8 but I will include both numbers as I am doing above. AD&D First Edition only used Small, Medium, and Large creatures. The vast majority will be these three sizes.

It is a beast, but also Demonic. So it's intelligence is higher and has some demonic traits. In this case, it can change shape, can only be hit by magic or silver, and has a special gaze attack.

I am also including a THAC0 line with a BAB in parentheses.

Things are shaping up.

[Fanzine Focus XXIII] Crawl! No. 7: Tips! Tricks! Traps!

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry. Another choice is the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game.

On the tail of the Old School Renaissance has come another movement—the rise of the fanzine. Although the fanzine—a nonprofessional and nonofficial publication produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, got its start in Science Fiction fandom, in the gaming hobby it first started with Chess and Diplomacy fanzines before finding fertile ground in the roleplaying hobby in the 1970s. Here these amateurish publications allowed the hobby a public space for two things. First, they were somewhere that the hobby could voice opinions and ideas that lay outside those of a game’s publisher. Second, in the Golden Age of roleplaying when the Dungeon Masters were expected to create their own settings and adventures, they also provided a rough and ready source of support for the game of your choice. Many also served as vehicles for the fanzine editor’s house campaign and thus they showed another DM and group played said game. This would often change over time if a fanzine accepted submissions. Initially, fanzines were primarily dedicated to the big three RPGs of the 1970s—Dungeons & Dragons, RuneQuest, and Traveller—but fanzines have appeared dedicated to other RPGs since, some of which helped keep a game popular in the face of no official support.Since 2008 with the publication of Fight On #1, the Old School Renaissance has had its own fanzines. The advantage of the Old School Renaissance is that the various Retroclones draw from the same source and thus one Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG is compatible with another. This means that the contents of one fanzine will compatible with the Retroclone that you already run and play even if not specifically written for it. Labyrinth Lord and Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay have proved to be popular choices to base fanzines around, as has Swords & Wizardry. Another choice is the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game.Published by Straycouches Press, Crawl! is one such fanzine dedicated to the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. Since Crawl! No. 1 was published in March, 2012 has not only provided ongoing support for the roleplaying game, but also been kept in print by Goodman Games. Now because of online printing sources like Lulu.com, it is no longer as difficult to keep fanzines from going out of print, so it is not that much of a surprise that issues of Crawl! remain in print. It is though, pleasing to see a publisher like Goodman Games support fan efforts like this fanzine by keeping them in print and selling them directly.

Where Crawl! No. 1 was something of a mixed bag, Crawl! #2 was a surprisingly focused, exploring the role of loot in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game and describing various pieces of treasure and items of equipment that the Player Characters might find and use. Similarly, Crawl! #3 was just as focused, but the subject of its focus was magic rather than treasure. Unfortunately, the fact that a later printing of Crawl! No. 1 reprinted content from Crawl! #3 somewhat undermined the content and usefulness of Crawl! #3. Fortunately, Crawl! Issue Number Four was devoted to Yves Larochelle’s ‘The Tainted Forest Thorum’, a scenario for the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game for characters of Fifth Level. Crawl! Issue V continued the run of themed issues, focusing on monsters, but ultimately to not always impressive effect, whilst Crawl! No. 6: Classic Class Collection presented some interesting versions of classic Dungeons & Dragons-style Classes for Dungeon Crawl Classics, though not enough of them.

As the title suggests, Crawl! Issue No. 7: Tips! Tricks! Traps! is a bit of bit of a medley issue, addressing a number of different aspects of dungeoneering and fantasy roleplaying. The issue opens with ‘Lost in Endless Corridors’ by Kirin Robinson. It contrasts the attraction and joy of the maze with the challenge of not making the play of mazes in fantasy roleplaying games, well, boring. What it highlights is the potential frustration of playing through a maze and the loss of player agency. It suggests two solutions to avoid this. The first is to set time limits on resources and character statuses during their exploration of the maze, such as their torches running out or their beginning to feel light-headed after a time. The second is move the exploration of the maze from being procedurally-based to clue-based, and so make the maze more interesting rather than an endless series of empty of corridors. This would need more work for the Judge than simply drawing out a map, but the potential pay-off would be greater and make the maze more memorable than frustrating.

Thom Hall’s ‘Roguelike Fountains’ is inspired by Roguelike computer adventure games, in particular, the fountains with their messages and effects to be found in such games. It comes with a number of tables for determining the nature of any fountain found and what its accompanying message might be. Thus magical or non-magical, and various effects and messages, with even the non-magical fountains often having some kind of effect. The use of the ‘Square’ font for tables, as used in the computer game adds to the nostalgic feel of the piece.

Sean Ellis continues his irregular Monster Column with ‘Consider the Ogre’. It points out the discrepancy between the Troll and the Ogre in Dungeons & Dragons, that the Dungeons & Dragons Troll with its rubbery skin and regenerative health is not the traditional Troll of myth and legend. That role actually falls to the Ogre. Although it does not suggest replacing one with the other, it does offer ways of making the Ogre more interesting than simply as a coarse, chaotic baby-snatching species of humanoids. It suggest the possibility that some might even be repentant and there might be multiple types of Ogre. This possibility is supported by tables for rolling an Ogre’s appearance and how different it is, and a power and a weakness, and then connecting the three together to create a cohesive design. Overall, it is a quick and dirty way of creating more individualistic Ogres.

‘Critical Table T: Traps – Traps and Crits’ by Jeffrey Tadlock details six traps ready to be placed in a Judge’s dungeon. These are simple enough—the spiked pit trap, the poison needle lock, the scythe hall, falling block, and repeating poison arrow trap—and arguably, classics of the fantasy gaming genre. Rather than have the Player Character affected by a trap make a saving throw against the effects of the trap when triggered, the Judge makes an attack roll against the Player Character for the trap. This means that traps, just as other forms of attack in the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game, need to have a table for determining what happens when a critical result is rolled on the attack. This is rolled on Critical Table T: Traps, a table of thirty results, the die rolled for any one trap determined by the attack modifier for the trap. So on a roll of one on any die, the trap springs perfectly and inflicts extra damage, but an attack modifier of +10 or +11 and the Judge is rolling a fourteen-sided die on Critical Table T: Traps, which might give the result of eleven, the damage inflicted strikes the target’s spinal area or if poison, overwhelms her central nervous system. Either way, the player needs to make a Fortitude Saving Throw for his character to remain conscious and the character also suffers two five-sided dice’s worth of extra damage. This makes traps even deadlier and makes the Thief Class far more important in disarming traps.

The ‘Shadowsword of Ith-Narmant’ is a write-up of a demonic shadow sword by Jürgen Mayer. It was forged from the demon’s own shadow by bound shadow warlocks and artificers, and like many of their creations may be found scattered across many worlds. It is treated as a longsword, but two six-sided dice are rolled for damage and when doubles are rolled, there is an extra effect, such as on double threes, ‘Taintburst’ inflicts three extra damage on the wielder and target, this damage, if it kills wielder or target, the demonic energies in the sword fuses with them, making them rise as a demon minion of Ith-Narmant. There are six such effects, one each for the six sets of doubles, but the very first, rolls of double ones, ‘Lifesucker’, sucks permanent Hit Points from the wielder and when enough is sucked out, the ‘Shadowsword of Ith-Narmant’ gains a Level. Each Level increases the viciousness and intelligence of the blade and inflict demonsigns on the wielder, which will have deleterious effects on the wielder’s alignment, ultimately turning him into a Champion of Ith-Narmant. The sword, ‘Shadowsword of Ith-Narmant’ is by any other name, Stormbringer from the novel by Michael Moorcock—or at least is inspired by it. Even if it is a bit too obvious, the mechanics are well done and bringing the sword into a campaign should give it an epic feel.

Rounding out the issue is ‘My Gongfarmer Can’t Do Sh*t!’ by Paul Wolfe. It is a call for the Zero Level characters of Character Funnel in Dungeon Crawl Classics to have skills and to be able to do things that reflect their backgrounds and occupations rolled during character creation. Not through an extensive list of skills, but rather through player creativity and narration when his Zero Level Player Character needs to do something which does not involve fighting, running, or screaming (or dying). It will require a little extra adjudication upon the part of the Judge, but the method will add to the background of any Zero Level character who survives a Character Funnel.

Physically, Crawl! Issue No. 7: Tips! Tricks! Traps! is decently put together. The few pieces of art vary in quality, some of it being a little cartoonish. The contents though, vary in quality and usefulness. This is not to say that none of the contents of the issue are useless, but none really quite stand out as being so useful that the Judge has to have access to them. The advice in ‘Lost in Endless Corridors’ and ‘My Gongfarmer Can’t Do Sh*t!’ feels a little obvious, unless of course, the Judge is new to Dungeon Crawl Classics, and whilst ‘Critical Table T: Traps – Traps and Crits’ and ‘Shadowsword of Ith-Narmant’ both add to the game, neither feels vital to a Judge’s game. Crawl! Issue No. 7: Tips! Tricks! Traps! feels like a mixed bag, containing good content, but just not good enough to be a must have.

#AtoZChallenge2021: A is for Allip

“El sueño de la razon produce monstruos”The sleep of reason produces monsters.Francisco Goya, 1799

“El sueño de la razon produce monstruos”The sleep of reason produces monsters.Francisco Goya, 1799It is April and that means it is time for the AtoZ Challenge for 2021. I didn't do this for a few years, but this year I wanted to give it a go again to see how it has changed, see what is new, and mostly to motivate me to get all my monsters done!

My monster book idea grew from my love of monster books in general. I have spoken about my love for the original Monster Manual here a few times. I have talked about other monster books too. For me it was monsters that were my gateway to D&D. I still love them.