Feed aggregator

October Horror Movie Challenge: Il Sesso Della Strega (1973)

Wait...didn't I watch this one last night? Well, you would think so just comparing the posters.

Wait...didn't I watch this one last night? Well, you would think so just comparing the posters.Also known as "Sex of the Witch" this one came out a year after Byleth did. Though in fairness BOTH movies do have a scene that the cover could represent.

An old wine merchant is dying so he curses his family, in particular his greedy grand-children.

One by one people start to die.

The plot, minus the sex and witchcraft, could have been a thriller or even a comedy. There are some parallels to some murder mysteries like Clue and Knives Out. In the sense that people keep dying and there are a bunch squabbling children trying to get Daddy's wealth.

There is lots of sex and nudity and it is pretty much the ultimate evolution of the Italian Giallo, Eurosleaze flick. It was only missing a deformed henchman in my mind. Though there is a creepy dude in black.

I will admit that I am now likely to use "fondling the goldfish" as a sexual euphemism after watching this movie. The said scene is about 40 mins into my copy.

It is notable that Camille Keaton of "I Spit On Your Grave" fame appears in this one as well as one of the nieces, Anna. she gets clawed by the previously mentioned creepy dude.

The movie's biggest crime though is that it is a slog and actually kind of dull.

Maybe a Byleth + Il Sesso Della Strega supercut is needed. In fact, I know just how to do it.At least we know what poster to use.

Watched: 6

New: 6

NIGHT SHIFT Content

The rich brother writes his sister out of his will because she was a witch and seduced him when they were younger. Now their illegitimate daughter is back. She is also a witch (more powerful since her blood is "concentrated") and begins to kill off all her half-siblings (they think she is "just" a cousin) so she can have all the inheritance for herself.Since she is a diabolic witch her patron is Byleth, the Demon Prince of Incest. While Byleth, or Beleth, has a history this version is closer to the D&D/Pathfinder demon Socothbenoth.

Now, this would obviously be a more R or even NC-17 rated game. To borrow a Scooby-doo trope one of the characters is a distant relative to the brother's wife (so no weird blood relations here).

The Official Music of the OSR is Run-DMC

Seriously. It is.

Like Old-School D&D was a pioneer of gaming, Run-DMC was a pioneer of old-school rap and hip hop. Many hip-hop groups cite Run-DMC as their primary influence and for many of us Run-DMC was out first exposure to the wider world of rap and hip-hop. Could there have been a Public Enemy without Run-DMC? Wu-Tang Clan? NWA? Snoop-Dogg? Outkast? Salt-n-Peppa, De La Soul? Cypress Hill? US3? Digable Planets? TLC? (damn, I still love TLC).

We owe it all to Run-DMC.

Silly? Yeah, a little. But my love of Run-DMC is pure and true. And yeah I know all the words to these songs.

But making a claim, any claim, about the OSR is pointless. While there are trends, there are no main drivers here. No one setting policy or dictating terms save for collective memory of a time when you could turn on your radio and hear "It's Tricky."

Consequently, the claim that OSR is conservative only track because the OSR is as has been often pointed out, full of old fucks.

I am pretty far left and get more liberal and more left and more blue with each passing year.

I shouldn't need to say this, but here it is.

Like THAC0 BLOG and The Elf Game, I don't just reject Nazis and White Supremacists, I utterly reject them and condemn them, and they are not welcome in any part of the games I play, write or enjoy. They can take their orange shitgibbon Trump with them.

Oh.

And Black Lives Matter.

And fuck Trump.

Don't like it? Get the fuck out of the OSR.

Monstrous Monday: Zombie Witch

Welcome to the FIRST Monstrous Monday of October 2020.

If you are on social media you might have seen this little gem from last week.

The answer of course is, me. I had Zombie Witches on my bingo card!

Well if I didn't I do now.

Photo by Thirdman from PexelsZombie Witch

Photo by Thirdman from PexelsZombie Witch

Medium Undead (Corporeal)

Frequency: Very Rare

Number Appearing: 2d4 (2d4)

Alignment: Chaotic [Chaotic Evil]

Movement: 90' (30') [9"]

Armor Class: 5 [14]

Hit Dice: 4d8+4** (22 hp)

Attacks: 2 claws + 1 bite, Cause Fear

Damage: 1d6, 1d6, 1d4

Special: Only harmed by silver, magic. Cause Fear 1x per day as per spell. Curse.

Size: Medium

Save: Witch 4

Morale: 12 (12)

Treasure Hoard Class: None; see below

XP: 100

When a powerful lord or lady dies they are often interred with fine weapons, treasures, and other grave goods that will support them in the after-life. But these lords also know that these good are desired by the less pious and greedy. So the lords will often arrange for a coven of witches to be sacrificed in a dark ritual and buried with the grave goods. The witches do not volunteer for this task, they are captured and sacrificed after the lords' death. It is believed that the anger of the witches will transcend death and the tomb will be protected.

This is true and the undead witch, now a mindless zombie will attack anything living that enters the tomb. Appearances may differ, but they are all undead witches in various states of decay or mummification.

Often lower level witches are used (under 6th level) and the only remains of their magic is a cause fear ability they can use as a group 1x per day. They then attack as fast-moving zombies (normal initiative). They will fight until they are destroyed. If the last zombie witch is destroyed and there are still combatants alive they will lay their final curse. Anyone taking goods away from the tomb must save vs. death or be afflicted with a rotting disease that drops their HP by 1d6 per day until death. Healing magics, potions, or other means will not stop the spread of the curse. Only a remove curse or similar magic can stop this curse. Then the victim can be healed.

If destroyed, zombie witches will reform by the next new moon. Only a cleric casting bless or a witch casting hallow or remove curse on the tomb will stop their return.

Zombie witches are turned as wights or 4HD undead.

Zombie Witch

(Night Shift)

No. Appearing: 2-8

AC: 5

Move: 30ft.

Hit Dice: 4

Special: 3 attacks (2 claw, bite), cause fear, bestow curse

Weakness: Vulnerable to silver, magic weapons and holy items. Holy water does 1d6+1 hp of damage to them.

If you want to see the other undead witches I have made over the years here is a list:

DMSGuild Witch Project: The Witch from Greg Baxter

Today I want to focus on a Witch class proper. I grabbed this one a bit ago and it has been languishing on my harddrive ever since.

Today I want to focus on a Witch class proper. I grabbed this one a bit ago and it has been languishing on my harddrive ever since.Again, here are my rules for these reviews of this series.

A lot of pdfs on DMSGuild are named "The Witch" and I guess I am not really any better on DriveThruRPG, so to distinguish them I am going to include the author's name in the titles.

This is an eleven-page PDF (8 pages of content, 1 cover, 1 title, 1 legal) that sells for $1.33 on DMSGuild (PWYW, suggested). So just a little over that 10 cents per page rule of thumb.

This product covers an entire witch base class.

These witches are very tied in with Hags and have the first witches as human women that have broken free from their transformation into hags.

The main ability of these witches is Intelligence.

The subclasses for this witch are Haglore Scholar, Athame Witch, and Rune Witch. They have a lot of flavor, to be honest, and would be fun to try out.

No new spells, but the spell lists are rather extensive covering the Player's Handbook and many of the other sourcebooks.

The art is minimal, but at least there are credits to the artists.

All in all there are some fun options here and I'd give them a try

Miskatonic Monday #53: The Mummy of Pemberley Grange

Best known as a manufacturer of props—both gaming and comic book related, Type 40 has now entered the actual gaming industry with the first of its ‘Seeds of Terror’ for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. Each Seed is designed to be concise and easy to run, and not only that, be easy to purchase, prepare, and run all within a single session. To that end, each includes a set-up and a plot, all of the necessary maps and handouts, and five ready-to-play pre-generated Investigators. The very first in the series is The Mummy of Pemberley Grange.

Best known as a manufacturer of props—both gaming and comic book related, Type 40 has now entered the actual gaming industry with the first of its ‘Seeds of Terror’ for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh Edition. Each Seed is designed to be concise and easy to run, and not only that, be easy to purchase, prepare, and run all within a single session. To that end, each includes a set-up and a plot, all of the necessary maps and handouts, and five ready-to-play pre-generated Investigators. The very first in the series is The Mummy of Pemberley Grange.The Mummy of Pemberley Grange: A 1920s Call of Cthulhu Seed of Terror for 4 or 5 investigators takes place at a country mansion in the 1920s to which the Investigators have been invited. Their host, Jessica Pemberley, rich socialite and Egyptophile, has shipped a mummy to her home all the way from Cairo and has invited them to an exclusive ‘unwrapping party’. This is a great event, an especially prestigious event which promises great, even macabre spectacle, made all the more so because of its intimacy, just a handful of attendees rather than the very public spectacle of a Mummy unwrapping as had occurred during the Victorian Era.

Essentially, the unwrapping in The Mummy of Pemberley Grange goes ahead as planned. Then something happens and the Investigators find themselves in a perilous situation—hunted from room to room and down corridor after corridor by a nigh-on unstoppable monster. All the Investigators have to do is keep out of the monster’s clutches and find a means to stop the threat facing them. Fortunately, everything that the Investigators needs is contained within the walls of Pemberley Grange—maps, clues, books, et cetera. The solution, once found, is gruesomely entertaining, though some players and their Investigators may find it quite unpalatable.

For all that there is a plot in The Mummy of Pemberley Grange, it is a simple plot and a straightforward plot. In fact, The Mummy of Pemberley Grange is primarily the set-up for a trigger event, and once that event is triggered, whatever happens next is driven by the actions of the Investigators. Aided, of course, by the occasional nudges from the Keeper in the form of the unstoppable monster…

The Mummy of Pemberley Grange comes with five ready-to-play pre-generated Investigators. They include an Egyptian archaeologist, a reporter, a businessman, a socialite, and a dilettante. Each comes with a little background, but for the most part, the players have plenty of space in which to create the details of their Investigators’ backgrounds. The three handouts are also well done.

However, there are a couple of issues with The Mummy of Pemberley Grange. The first is the map, which shows the floorplans of Pemberley Grange. The floorplans are in fact excellent and have a period feel, but they are only of the ground floor. Which is a bit of a problem should the Investigators want to go upstairs. The second is that there are twenty or so locations given on the map, but only a handful are given any description, which means that the Keeper is going to have to make up whatever might be found in these rooms. This should not be a problem if the Keeper has watched her fair share of episodes of Downton Abbey or Poirot, but if not, the flavour and feel of the scenario might suffer, let alone the pacing if the Keeper has to improvise too much.

Physically, The Mummy of Pemberley Grange is presented and easy to read. The handouts and the map are available to download separately, as are the Investigator sheets. They are also easy to use.

A classic Mummy unleashed horror scenario rather than a Mythos scenario, The Mummy of Pemberley Grange has potential to be great fun and the nature of its monster and set-up makes it easy to run as a Cthulhu by Gaslight scenario during the Victorian Era. Equally, it could be shifted to the USA or Australia just as easily—or another country with a few name and language changes. In fact, those changes would only take a few minutes, but really, that would only double the set-up time, because The Mummy of Pemberley Grange really can be downloaded, read through, and prepared in ten minutes—and that is being generous. Overall, The Mummy of Pemberley Grange really delivers on its low preparation promise; after that, it is up to the Keeper to deliver the horror and the Investigators to run scared as the Mummy stalks them in the halls of Pemberley Grange.

—oOo—

A full play through of The Mummy of Pemberley Grange is available to watch on YouTube recorded as part of Melbourne International Games Week.

October Horror Movie Challenge: Byleth: The Demon of Incest (1972)

This is another one from last year. The Blu-Ray was not available till November, so here we are. This is another one of those notorious movies of the 70s Euro-sleaze horror. One I had been looking for a while mostly because I never thought I'd find it.

This is another one from last year. The Blu-Ray was not available till November, so here we are. This is another one of those notorious movies of the 70s Euro-sleaze horror. One I had been looking for a while mostly because I never thought I'd find it.Byleth: The Demon of Incest is a little Italian gem that features murders, gratuitous nudity and enough brother/sister incest for an episode of Game of Thrones.

Let's get right to the point. It's not good. It is slow and the lead Mark Damon as Duke Lionello is not great.

The movie revolves around Duke Lionello, his sister Barbara and Barbara's new husband Giordano. This is a problem of course since Lionello and Barbara have been having an incestuous affair. An affair that Lionello is loathed to give up.

The movie does make use of the demon Beleth, which is expected. At one point Barbara asks her brother, Lionello, if he still has his white horse. They later talk about "Byleth" on his white horse.

Of course, you are never sure if Lionello is possessed by Byleth or just crazy. I like to think possessed because that is what I do here.

The Severin Blu-Ray version is really good. There are some color issues from the original negative, but otherwise, it looks great. Too bad the movie could not live up to the hype.

Watched: 5

New: 5

NIGHT SHIFT Content

Come back tomorrow night for my ideas on this one!

Nika Goltz (1925–2012)

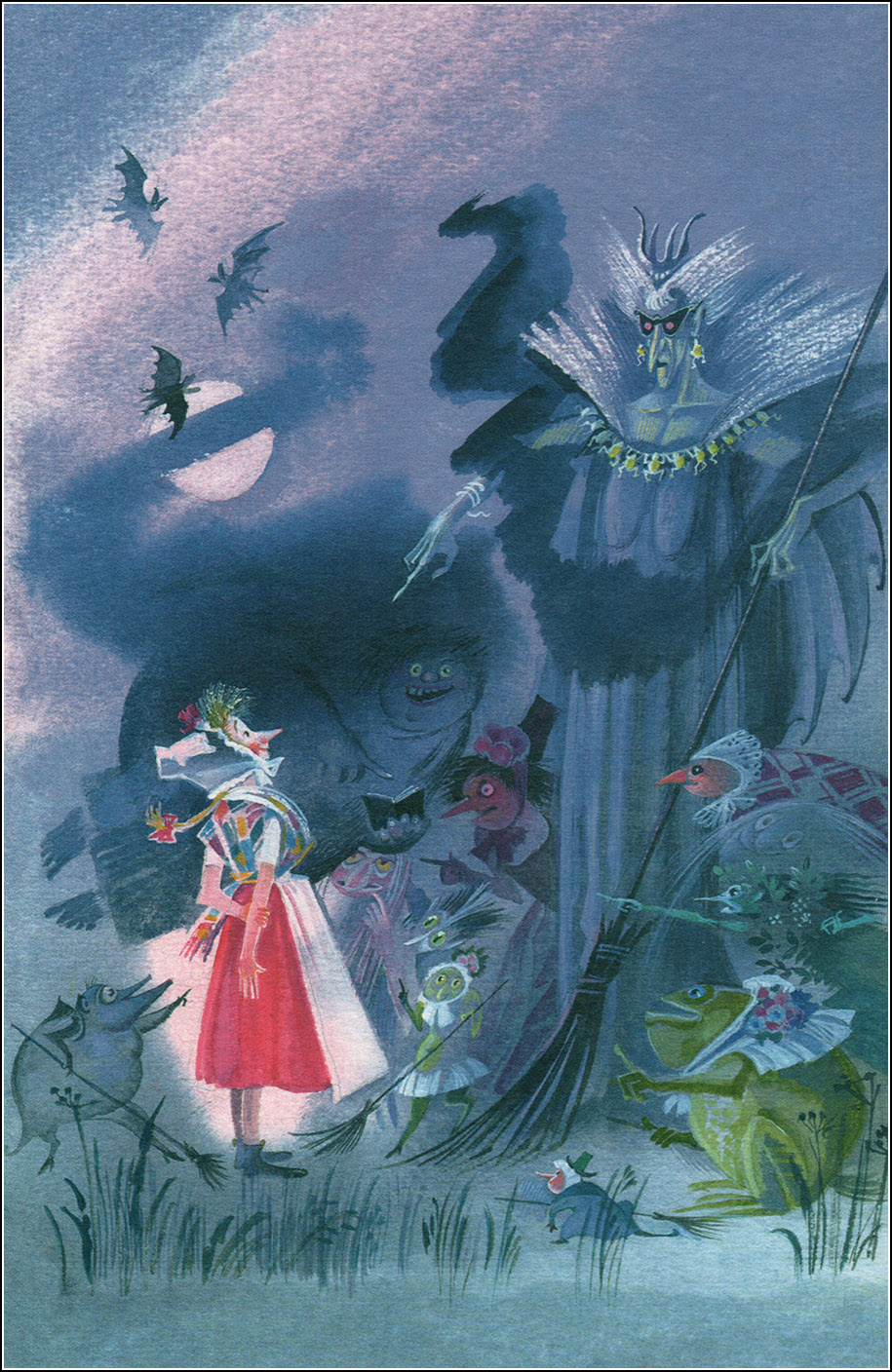

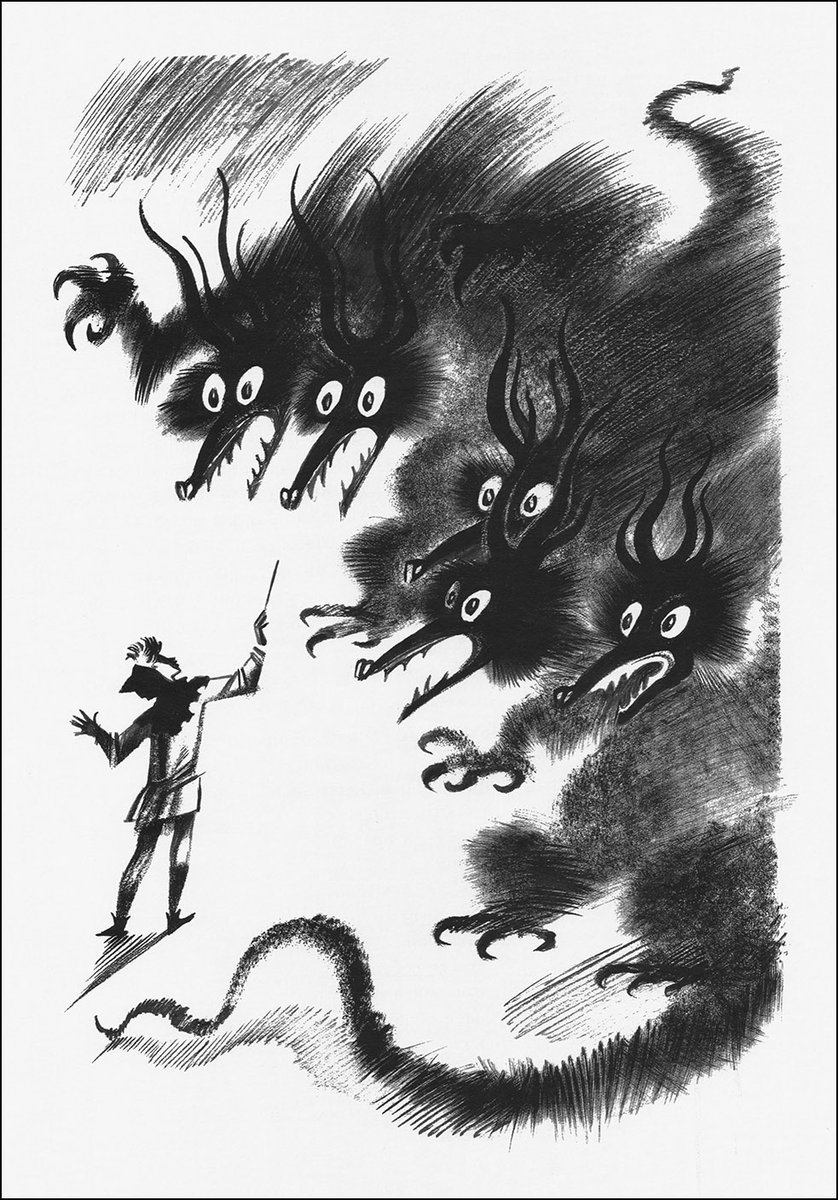

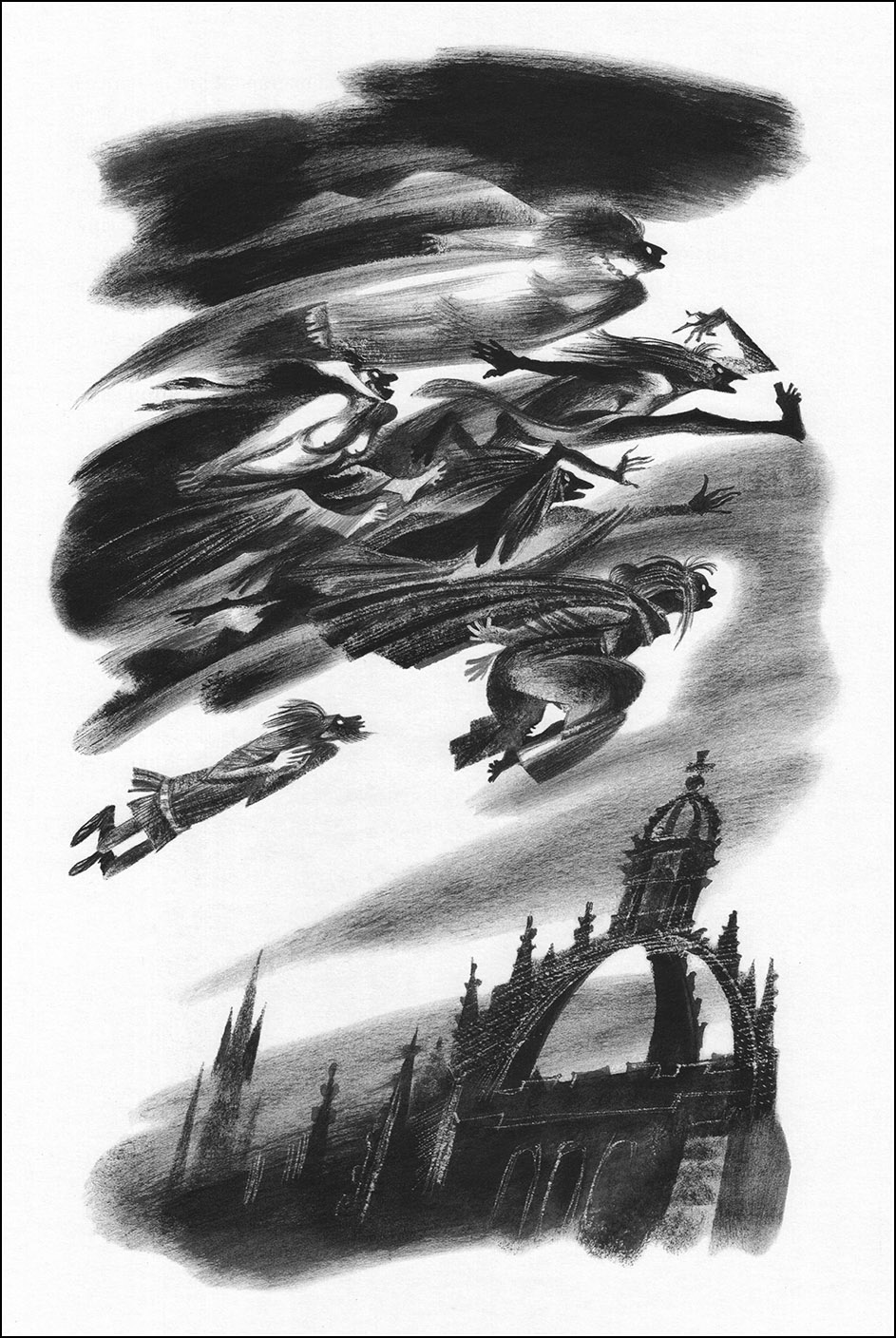

Illustration from "The Snow Queen"

Illustration from "The Snow Queen"  Illustration from "The Little Witch"

Illustration from "The Little Witch"  Illustration from Alexander Sharov's "Wizards Come to the People" The book about Fairy Tales and Storytellers.

Illustration from Alexander Sharov's "Wizards Come to the People" The book about Fairy Tales and Storytellers.  Illustration from Otfried Preussler's "The Little Water-Sprite"

Illustration from Otfried Preussler's "The Little Water-Sprite"

Illustrations from "English Folk Tales"

Illustrations from "English Folk Tales"

Illustrations from Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid"

Illustrations from Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid"

Illustrations from "Scottish Folk Tales and Legends"

Illustrations from "Scottish Folk Tales and Legends"

Illustrations from Otfried Preußler's "The Little Ghost"

Illustrations from Otfried Preußler's "The Little Ghost"Most artworks found at Book Graphics.

Artist previously shared here.

Psycho-Sexual Killer Qu'est-ce que c'est

Lover in the Ice, a scenario for Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game carries the proviso that it is, “Recommended only for the most resilient players and Agents”. Be advised that this warning is well deserved, for the horror in Lover in the Ice is of a horrifyingly adult nature, being body horror akin that of the 1979 film Alien, but combines it with the almost viral-like vector of John Carpenter’s The Thing and a psycho-sexual drive of a David Cronenberg film that ramp up its intimately sexual elements to disturbing levels. Whilst most horror scenarios are of an adult nature and require a mature audience, the horror in Lover in the Ice is of an unremittingly intense, if not extreme timbre, which would be very difficult to tone down. However, if a playing group is prepared for it and are forewarned about the strength—though not necessarily the nature—of horror in its pages, Lover in the Ice will deliver a memorably vile investigation into something that should not be…

Lover in the Ice, a scenario for Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game carries the proviso that it is, “Recommended only for the most resilient players and Agents”. Be advised that this warning is well deserved, for the horror in Lover in the Ice is of a horrifyingly adult nature, being body horror akin that of the 1979 film Alien, but combines it with the almost viral-like vector of John Carpenter’s The Thing and a psycho-sexual drive of a David Cronenberg film that ramp up its intimately sexual elements to disturbing levels. Whilst most horror scenarios are of an adult nature and require a mature audience, the horror in Lover in the Ice is of an unremittingly intense, if not extreme timbre, which would be very difficult to tone down. However, if a playing group is prepared for it and are forewarned about the strength—though not necessarily the nature—of horror in its pages, Lover in the Ice will deliver a memorably vile investigation into something that should not be…Published by Arc Dream Publishing, what Lover in the Ice has in common with so many other scenarios for Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game, is that it is about ‘Investigation, Containment, & Denial’—and it really plays up the Containment angle. As is tradition for a Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game scenario, it begins with a telephone call. The Agents are to go to Lafontaine, Missouri which is currently caught up in an apocalyptic ice storm which has shut down and isolated the town. As the Agents may come to realise, although this might hamper their investigation, this is a very, very good thing. An alert has been triggered on a Green Box, one of the private storage areas—typically a rental storage unit, but it could be the boot of a car in a used vehicle dealership—where Agents can store valuable resources such as equipment and arms and materiel, as well as dump evidence of their activities and investigations in relative safety. In this case, the Green Box is at a storage rental facility in Lafontaine and the Delta Green ‘Friendly’—the employee at the facility paid to keep an eye on its has not responded. The Agents need to ride the relief efforts in Lafontaine, locate the ‘Friendly’ and find out what he knows, then verify the contents of the Green Box, determine if any of it is missing or has been stolen, and if so, get it back.

This though, is only the start. The Agents will at least need to establish the veneer of their cover before launching the investigation proper, but clues can be found almost from the off, and the Investigators are likely to be faced by a steady flow of them as they conduct their investigation—almost dauntingly so. The players really do need to be taking notes throughout and linking the clues to gain an understanding of both the backstory and what is actually going on—and ultimately, the threat that represents. Which means that the handler needs to read Lover in the Ice carefully to have that understanding herself. For the most part, the clues veer from signs of weirdly sexual activity to bloody murder scenes and back again, but the author gives the Agents a pause early in the scenario with an inventive array of weird and peculiar artefacts and not-tomes—mostly unexplained—which they need to examine and verify that were stored in the Green Box. Of course, major clues as to what was going on can be found here too, and the Agents are likely to suspect that they tie into some the oddness they will already have discovered. All of this should hopefully prepare them for the horribly bloody, even intimate encounters and confrontations with the threat at the heart of Lover in the Ice which become more dangerous each time they happen.

The environment for the investigation in Lover in the Ice also plays a part, although not as an active a part as you would think, and a Handler might want. It has two effects, one immediately obvious, one not. Not wanting to spoil the nature of the not so obvious one, the primary and obvious effect of the ice storm is to constrain the limits of the investigation. Not just in terms of geography, but also in the size of the cast in the scenario—the Handler really only has the one NPC to roleplay throughout the whole scenario. This only serves to heighten the sense of isolation in Lover in the Ice already present from limitations upon the physical senses due to the storm and the weather and the limited capacity to contact the outside world. However, the weather has no other physical effect on the scenario, and it will be up to the Handler whether she wants to enforce the effects and limitations upon her Agents when investigating in a severely cold environment.

As constrained as the environment for Lover in the Ice is, one of its major problems is that it is lacking a map of Lafontaine. The investigation has a Geographic Profiling aspect to it, and it would have been nice if the Agents had been able to spread open a map and plot the clues on a handout. The other issue is that not all of the monster NPCs are given stats. Neither problems are insurmountable, and the Handler should be able to create both the stats and a map with a little effort. That said, she should not have to, given that the last two pages of Lover in the Ice consist of a Delta Green Agent sheet, which to be honest, is superfluous here.

Lover in the Ice is very much a player and their Agents driven scenario. Its plot is already in motion and the Agents are essentially tracking that down in order to contain the threat. Again, a map of the location for the scenario’s denouement—climax would probably have been an inappropriate description—would have been useful, but again the Handler should be able to find one. In comparison to the investigation, the denouement does feel slightly underwritten, but the conclusion does highlight how the Agents’ failure to contain the situation in Lafontaine is likely to turn into a storm of another nature…

Physically, Lover in the Ice, as with so many other scenarios for Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game, is for the most part neatly laid out and well written. Its clues and handouts are nicely done and the details on the floorplans included are a huge improvement in terms of detail in comparison to other scenarios.

Essentially, The Thing in the ‘Show Me State’—as Missouri is also known—the likelihood being that the players will be going, “No, please don’t show me!”, is as nasty a slice of physical horror that Delta Green: The Roleplaying Game has ever served up. Its adult tone and the nature of the horror simply will not be for every player—and the Handler should take that into account when deciding to run Lover in the Ice. If however, the Handler does decide to run it and with the right group of player, Lover in the Ice combines a rich welter of clues and investigation with desperately disturbing horror.

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Sonata (2018)

This was a fun one. It reminds me a bit of "The Mephisto Waltz" and a little bit of the "Music of Erich Zahn", only in reverse.

This was a fun one. It reminds me a bit of "The Mephisto Waltz" and a little bit of the "Music of Erich Zahn", only in reverse.Rose Fisher (Freya Tingley) is a world-class violinist and she learns that her estranged father, and brilliant strange composer, Richard Marlowe (Rutger Hauer) is dead.

She inherits his home and all his belongings including a very strange violin sonata. Her agent Simon Abkarian (Charles Vernais) investigates and learns that the sonata was part of a work linking it to a cult of Satan worshipers in France and it appears to have been written just for Rose.

The movie is more of a thriller, but there is the summoning of the antichrist and the ghosts of the children sacrificed by Marlow in the process of composing his masterpiece sonata.

The movie was rather good. Frey Tingley is great as Rose and I wanted more Rutger Hauer.

The end was a nice little twist so I enjoyed that.

I am a sucker for any story that mixes music with magic.

Watched: 4

New: 4

NIGHT SHIFT Content

Frankly, I would lift this plot wholesale to use as a NIGHT SHIFT adventure. Investigate the scary mansion of a composer that commits suicide. Horrible tapes found in the basement. All sorts of great things here. Though stopping it would require an active antagonist.

Brilliantly Sunny Handouts

As well as introducing players to the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft and the concept of playing ordinary persons—or investigators—pitched stopping the entities and their servants borne of an uncaring universe, Call of Cthulhu introduced something else. And that is, clues, and in particular, their associated handouts. For Call of Cthulhu is a literary game and an academic game, a game in which clues come in the form of letters, diaries, newspaper clippings, excerpts from Mythos tomes, and more. Which of course, means that they can all be copied and cut out for the players and their investigators’ perusal, and from the clues found, so push the play of the game forward. As scenarios and then campaigns grew in complexity, then so did their clues, and then so did their handouts...

As well as introducing players to the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft and the concept of playing ordinary persons—or investigators—pitched stopping the entities and their servants borne of an uncaring universe, Call of Cthulhu introduced something else. And that is, clues, and in particular, their associated handouts. For Call of Cthulhu is a literary game and an academic game, a game in which clues come in the form of letters, diaries, newspaper clippings, excerpts from Mythos tomes, and more. Which of course, means that they can all be copied and cut out for the players and their investigators’ perusal, and from the clues found, so push the play of the game forward. As scenarios and then campaigns grew in complexity, then so did their clues, and then so did their handouts...Of course, the first sophisticated handout for Call of Cthulhu would arguably be the match book for the Tiger Bar in the Shanghai chapter of Masks of Nyarlathotep, and in some ways, just as Masks of Nyarlathotep has remained the preeminent campaign for Call of Cthulhu, so its handouts have remained as correspondingly important. Thus to accompany the most recent edition of the campaign, updated and adjusted for use with Call of Cthulhu, Seventh edition, The H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society has created the Masks of Nyarlathotep: Gamer Prop Set. With its one hundred and more props and handouts, this—even in its standard form—is a gorgeous looking collection and would deservedly go on to win the 2019 Ennie Award for ‘Product of the Year’. (Note that Reviews from R’lyeh has only had a chance to examine the Masks of Nyarlathotep: Gamer Prop Set and is not ashamed to admit that it would like to write a review of this and other prop sets.)

However, not every campaign or scenario warrants so lavish a treatment, but over the years there have been many efforts to support Call of Cthulhu’s use of handouts as props. For example, Chaosium, Inc. published the Beyond the Mountains of Madness Game Aid, which collected all of the handouts and supporting material for the pre-millennium campaign, Beyond the Mountains of Madness Game Aid. Similarly, Pagan Publishing published GM Packs for many of its campaigns, such as that for Realm of Shadows. Many of these extras have become highly collectible, with correspondingly high prices, even though in some cases, they have not amounted to much more than a few sheets of paper.

Alongside this, another trend has allowed the Keeper to create more and more of her own handouts—the use of the personal computer and inexpensive Desktop Publishing software. Previously, a Keeper might have written out a handout and then soaked it in tea before drying it out in the oven to get that effect of its being old, and whilst she might still do that today, she is just as likely to create something her computer—a letter, a diary entry, a newspaper article, a map, and the like. This also means that publishers can do the same, whatever their size. So it is with Dave Sokolowski and Weird 8, who has released the Sun Spots Prop Kit, a set of handouts for the 2016 scenario, Sun Spots. Set in 1926, west of a wintery Boston in the resort town of Red Valley where sun-worshippers are taking advantage of the unseasonably warm weather and a father—accompanied by the investigators—have come to retrieve his daughter, whom he believes to have fallen into immoral company. Of course, nothing is as it seems, for that immoral company turns out to be sun-worshipping cultists, more and more of whom flocks to the town the heat grows and grows, threatening burn it—and more—down.

The Sun Spots Prop Kit is a simple envelope, inside of which are just four items. The first of these is the first of three maps in the Sun Spots Prop Kit. This is an A3-sized, double-page spread of the town, drawn in topographical style, and done as the sort town map you might find at a tourist office or a hotel. It even comes with marked and numbered location as well as list of adverts down one side. This gives it a lovely verisimilitude. The second prop consists of several entries in the daughter’s diary over a couple of sheets and they are nicely presented with a slightly rough and idiosyncratic feel to the handwriting. The handwriting is large and easy to read, but with elements that make it just a little harder to read in places—just like the handwriting of you or I.

The second map—and third prop—is a simple plan of the town of Red Valley. This feels much more a handout rather than an in-game map like the first one, but is clear and simple. The likelihood is that this map was designed to accompany the third map—and fourth prop, an elevation map of the valley around the town of Red Valley. Now in Sun Spots, only the fourth prop was included in its pages, rather than including a map of the town. So, the Sun Spots Prop Kit certainly fixes that omission. Of the two maps, the elevation map is the only one done in full colour and it has a pleasing delicacy to it matching the area maps of the period.

Physically, the Sun Spots Prop Kit is solidly presented. All four items are printed on weighty paper stock and feel good in the hand.

The Sun Spots Prop Kit is smartly done and all four props have a lovely feel to them. Now if you have a copy of Sun Spots, then the truth is that the props in the Sun Spots Prop Kit are not entirely necessary to play the scenario. However, they do add a degree of verisimilitude when running the scenario—especially the tourist-style map and the diary. Which means that the Sun Spots Prop Kit does what it is intended to do and that is, help make the play Sun Spots all the better.

Mutant Cosmic Horror

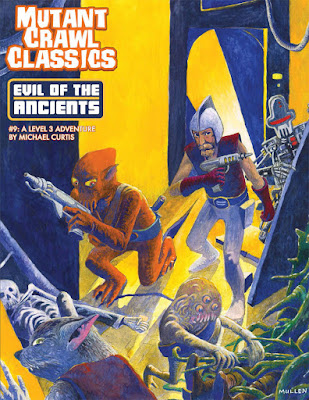

Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is the eighth release for Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic, the spiritual successor to Gamma World published by Goodman Games. Designed for Third Level player characters, what this means is that Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is not a Character Funnel, one of the signature features of both the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game and the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game it is mechanically based upon—in which initially, a player is expected to roll up three or four Level Zero characters and have them play through a generally nasty, deadly adventure, which surviving will prove a challenge. Those that do survive receive enough Experience Points to advance to First Level and gain all of the advantages of their Class. In terms of the setting, known as Terra A.D., or ‘Terra After Disaster’, this is a ‘Rite of Passage’ and in Mutants, Manimals, and Plantients, the stress of it will trigger ‘Metagenesis’, their DNA expressing itself and their mutations blossoming forth. By the time the Player Characters in Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients reached Third Level, they will have had numerous adventures, one of which might have been Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension. This is important because both scenarios are written by Michael Curtis and because Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients can be played as a sequel to Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension.

Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is the eighth release for Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game – Triumph & Technology Won by Mutants & Magic, the spiritual successor to Gamma World published by Goodman Games. Designed for Third Level player characters, what this means is that Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is not a Character Funnel, one of the signature features of both the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game and the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game it is mechanically based upon—in which initially, a player is expected to roll up three or four Level Zero characters and have them play through a generally nasty, deadly adventure, which surviving will prove a challenge. Those that do survive receive enough Experience Points to advance to First Level and gain all of the advantages of their Class. In terms of the setting, known as Terra A.D., or ‘Terra After Disaster’, this is a ‘Rite of Passage’ and in Mutants, Manimals, and Plantients, the stress of it will trigger ‘Metagenesis’, their DNA expressing itself and their mutations blossoming forth. By the time the Player Characters in Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients reached Third Level, they will have had numerous adventures, one of which might have been Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension. This is important because both scenarios are written by Michael Curtis and because Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients can be played as a sequel to Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension.In Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension visited a strange island off the coast, home to a scientific research facility which has been invaded by, guess what, an Incursion of the Ultradimension. It combined a sense of the weird with a hint of Blue Collar Science Fiction Horror a la the 1979 film, Alien. The facility also contained a map indicating the location of other facilities in the time before Terra A.D., which might actually still be found, possibly even found intact, in the here and now of Terra A.D. The location for Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is such facility located on the map. However, it need not be run as a sequel, but simply as an encounter along the way as the Player Characters travel from one place to another. However, it may lose a certain resonance if played as a standalone and playing Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients as a sequel to Mutant Crawl Classics #3: Incursion of the Ultradimension will go towards building a sense of a campaign, something that is not necessarily a strong feature of the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game.

Most scenarios for Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game are a combination of the gonzo and the weird, Science Fiction with an element of fantasy. Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is different in that it is less fantasy and less gonzo, and very much a weird horror scenario. Once the Player Characters descend into the facility, they at first find scenes of death, but the more they explore, they find that these deaths appear to be the result of a manic outbreak of madness and violence. Of course, the apocalypse that brought Terra A.D. into being, killed millions, but in many of the thirteen rooms and corridors underground, the Player Characters will discover signs of the staff having run amok, signs of their not only having inflicted bloody violence, but of have actually committed acts of torture upon each other. The question is, what drove them to act in such a way?

What drove them to act in such a way was an extra-dimensional creature, a thing dragged into this world by the comic researches being conducted at the facility—think the Large Hadron Collider, but significantly more compact—and in its efforts to persuade the scientist to find a way of getting it home, its viral emanations drove the staff mad and they killed each other. Unfortunately, for the Player Characters, it is still trapped, and it still wants to get home, and it will go to any means to make it possible, even if it means sacrificing a sufficiently powerful enough psychic mutant as part of the process. Which means communicating with the Player Characters, which means that just like the facility before them, it means driving the Player Characters crazy! And is something of a problem when it comes to running Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients as part of a campaign.

Essentially, Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is a haunted house scenario whose horror is cosmic in nature. Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game is not a horror roleplaying game and does not have a Sanity mechanic a la Call of Cthulhu, but as the Player Characters explore the facility, they will receive—initially, but then eventually suffer echoes of memories of the staff before they died, and then when they died. It is horrific and it is horrible, and worse, the most terrible of memories not only inflict harm on the Player Characters, they also force the Player Characters to inflict harm on both each other and themselves—and that is a big problem.

Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game is not a horror roleplaying game and so does not normally deal with situations in which the Player Characters are trapped in a closed environment and in some cases driven to inflict bloody torture on each other and themselves. In a horror scenario for a horror roleplaying game, this would not be as much of an issue because it is within the remit and the nature of the genre. In the post-apocalyptic genre of the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game it is so much. So as consequence, the first issue with the scenario is that it should have included warnings as to its nature and the traumas it entailed. The second issue is that the scenario’s events and traumas are divisive and will see the Player Characters acting against each other—physically and mentally given that this is a scenario for the Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game. Ultimately, this could see the Player Characters killing each other, potentially leading to a ‘Total Party Kill’, and not every group will be happy with this. For such a group, it could break the game or even the group itself! And again, the scenario should have included warnings as to its nature and the traumas it entailed.

However, if the players are happy with the horrific nature of Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients, then it is a horrifically atmospheric scenario, its creepiness building and building as the Player Characters encounter memory echo after memory echo and become aware of the true nature of past events in the underground facilities. Ultimately, it is likely to lead to an outbreak of bloody violence amongst themselves, and perhaps their best course of action is to retreat, to count the exploration as at best, a horrifying experience best left unrepeated. Its horrible nature means that it also works as a one-shot, and its short length, means that it could also be played in a single session, possibly as a convention scenario (doing so, would definitely require the warnings that the scenario is sadly lacking).

Lastly, it should be pointed out that Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients discusses possible outcomes to the scenario and gives an alternative ending involving a more physical confrontation—rather than the Player Characters running away. An appendix details the viral nature of the threat they will face in the scenario.

Physically, Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is nicely presented. It needs an edit in places, but is generally well written and the artwork involves a lot of the signature characters seen in other Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game titles. The double-page spread map is excellent though.

For all of its issues, Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients is a good scenario—creepy and weird, with a growing sense of horror as the Player Characters explore the facility. However, the scenario is also nasty in its horror, and some playing groups are not going to be happy with that and its divisive effects, especially in a game like Mutant Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game which normally does not feature either. The Judge is advised to read the scenario carefully and consider its effects on her campaign and her players before running Mutant Crawl Classics #8: Evil of the Ancients, and perhaps if Goodman Games publishes a scenario of a similar nature in the future, advisory warnings might be a good idea.

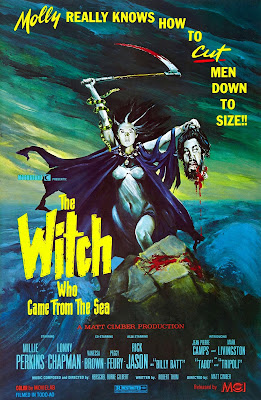

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976)

Another "leftover" from a previous challenge.

Another "leftover" from a previous challenge.This might be the most "1976" movie I have seen in a long time. Lots of drugs, naked hot tubbing, and a busted up Volkswagen Karmann Ghia.

The main character, our "Witch", Molly is fairly insane. She tries to repress the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father while lusting after all these different men.

She also seems to be killing men but not remembering it.

Molly is not just deranged, she is also very simple like she is still stuck somehow back at being a child.

Molly keeps spiraling deeper into madness and the police are quickly on to her.

In some of her flashbacks, it's hard to tell what was real and what is only her delusional state. So she either killed a few men or a lot of them.

What I don't get is how in the hell did she get up and kill people with all those drugs and alcohol in her system.

IMDB said this movie had witchcraft in it, but not really.

There is horror here, but not of the conventional sort.

Watched: 3

New: 3

NIGHT SHIFT content

Not every supernatural occurrence is a bad one as I have tried to show in Ordinary World. Some times the supernatural occurrence is not even really supernatural. In the case of this movie, there is a supposed "witch" but really it is just a mentally disturbed woman that kills men. A ruse like this only works once to be honest so use it sparingly. Too much and you turn your "Supernatural Horror" into "Scooby-Doo."

Friday Night Videos: The Hex Girls

It's Friday! It's October! Let's start some Friday Night Videos!

Since I am also doing my October Horror Movie Marathon posts I am writing these posts early to autopost.

So let's get started.

Tonight I have the music of my favorite all-girl, eco-goth band of witches, the Hex Girls! Not just the songs from their Scooby-Doo episodes but some clever coplayers and cover bands.

And all the Hex Girls songs in one place.

Happy Halloween!

Have a Safe Weekend

October Horror Movie Challenge: The Horrible Sexy Vampire (1970, 1971)

Well. One of the words in the title is a lie, but one is spot on.

Well. One of the words in the title is a lie, but one is spot on.Also known as "El Vampiro De La Autopista" this is a movie that never really knows what it wants to do. Both titles tell us this is a Vampire film, but it is often treated (right up to the end in fact) as a mundane murder mystery. They make a big deal of the murders happening every 28 years, but the ending does nothing to explain that.

Not to spoil it, but the movie is kind of dull, the police detective pins the murders on an escaped mental patient. One we don't even hear about till the very end. This is despite the fact that the murders have an obvious supernatural element to them. How obvious? Well, the killer is invisible.

Now under other circumstances, this might be interesting, but here it is just cheesy.

Sadly some interesting ideas lost in this Spanish "Hammer-envy" movie.

Watched: 2

New: 2

Night Shift ContentWell. The best thing to do with this one really is to have a serial killer in your games. Everyone thinks it is a vampire, but it really just a human psychopath. This works well in Ordinary World if all the characters are supernatural and they are worried that one of their own is going to get them exposed.

Kickstart Your Weekend: Bitchin Chimera and the Jaquays' Archive

Quite the collection today!

Lost Tomb of the Bitchin' Chimera - Dead Milkmen RPG Module

The Dead Milkmen are releasing a D&D adventure about a "Bitchin Chimera." Do I really need to tell you more than that? No idea if Tony Orlando and Dawn, Beelze-bubba, Mojo Nixon, or a Punk Rock Girl will appear.

Judges Guild Deluxe: Dark Tower, Caverns of Thracia, & More

Ok, first and foremost this Kickstarter will not benefit any of the current racist owners of the Judges Guild. This collects some of the best material of the early days of JG and all written by Jennell Jaquays. Some very, very solid stuff here, and Goodman Games puts out a solid product.

and finally one more look at this one now that it has made it's funding goal.

Hellbringers: The Sacred Heart

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/hellbringers/hellbringers-the-sacred-heart?ref=theotherside

All are ending soon!

DMSGuild Witch Project: Witches of Rashemen

Today I have three products again that work well with each other, but this time they are not by the same author.

These products all deal with the area of the Forgotten Realms known as "The Unapproachable East" and Rashemen in particular. This is of course one of the strengths of doing a product for the DMSGuild as opposed to doing it via the OGL; the ability to access Wizard's IP to use.

While that is certainly attractive in some cases, I much prefer to use the OGL. But if these authors had then we not have these products.

Again, here are my rules for these reviews of this series.

The Great Dale Campaign Guide

The Great Dale Campaign GuideThis one is huge and has ten authors. The pdf and hardcover book fills it's 144 pages with full-color art and details on all sorts of details on the Great Dale section of the Unapproachable East. This book actually rivals such books from WotC like The Sword Coast guide and the Icewind Dale. This book covers the people of the lands with new classes (sub-classes), new backgrounds, new feats as well as new spells and magic items. The lands are covered with geography, history, factions, friends, and foes. There are guides for playing in the lands as well. The author's introduction sets the stage for the book AND I think it also a good selling point for why people would want to use the DMSGuild rules over the OGL.

In the case of this book it works well. I also appreciate that authors not only took the time to properly credit the artists, the obtained commissions for some art as well. This more than justifies the $19.95 price tag for the PDF. It is also one of the few DMSGuild books I would want as a hardcover too. If I played in the Realms more. If I ever get a Realms 5e going then this will be on my list for getting the hardcover version.

While the Witches of Rashemen are mentioned, there is no "Witch" class. Plenty of Warlock and Wizard sub-classes though.

Spells of the Unapproachable East

This is a modest PDF that punches above its weight class. It gives us 13 pages of 5e style spells that are conversions of earlier spells from the Unapproacble East area. A few I recognized from Unapproachable East (3.5) and from Spellbound (2e). No art, but 39 spells that were not part of the D&D 5 corpus at the time the PDF was made. All of that for just a PWYW of $0.50. Not to bad really.

Again, no Witch class in this one. But plenty of spells.

Homebrewed Class: Wychlaran Witch

Ah! Now here is what I have been wanting. You can't write about witches in D&D as long as I have and not come across the Wychlaran Witch, the Witches of Rashemen. It was one of the reasons I finally put down my Greyhawk books to see what this "young upstart" of the Forgotten Realms was about.

This PDF is modest, only 8 pages, written by Bryan Williams. It covers the Wychlaran Witch class as a full class. It covers the class and all the class features, but it is missing the advancement tables and spells per level. It looks and reads like it should be akin to a sub-class of the Sorcerer, and that works to a degree, still I would have liked to see the table. There is a section on new equipment, which is good, and 13 new spells. I supposed the advantage to this particular PDF is if you have a Witch class you like you can use this in conjunction with it to create a more witch-y Wychlaran. So that is a bonus in it's favor.

Also the PDF is PWYW with a listed price of $0, but I say use my guideline of ¢10 per page and give the author ¢80 (or ¢60 for the actual content). For less than...well just about everything, you can have a class and some new spells.

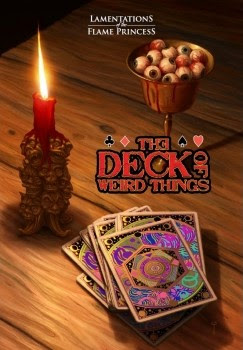

[Friday Fantasy] The Deck of Weird Things

Dungeons & Dragons has given the hobby a great many things, many of them signature things. In terms of treasures and artefacts, none more so than The Deck of Many Things. Since it appeared on page one-hundred-and forty-two of the Dungeon Master’s Guide for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, First Edition in 1979, The Deck of Many Things has been a wondrous thing, an artefact which dealt out fantastic gifts—both beneficial and baneful, which wrought amazing changes upon a Player Character and the world around them. These ranges from being given a beneficial miscellaneous magic item and fifty thousand Experience Points, being granted between one and four wishes, gaining an enmity between the Player Character and a devil to the Player Character losing all of his magical items—all of them and forever, having their Alignment radically changed, and being imprisoned—instantly! Once found and as each card is drawn from The Deck of Many Things, that card will change the drawing Player Character, the world about him, and the campaign itself. The Deck of Many Things is not just a wondrous artefact, but very probably, a box/bag—whatever it came in, of chaos.

Dungeons & Dragons has given the hobby a great many things, many of them signature things. In terms of treasures and artefacts, none more so than The Deck of Many Things. Since it appeared on page one-hundred-and forty-two of the Dungeon Master’s Guide for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, First Edition in 1979, The Deck of Many Things has been a wondrous thing, an artefact which dealt out fantastic gifts—both beneficial and baneful, which wrought amazing changes upon a Player Character and the world around them. These ranges from being given a beneficial miscellaneous magic item and fifty thousand Experience Points, being granted between one and four wishes, gaining an enmity between the Player Character and a devil to the Player Character losing all of his magical items—all of them and forever, having their Alignment radically changed, and being imprisoned—instantly! Once found and as each card is drawn from The Deck of Many Things, that card will change the drawing Player Character, the world about him, and the campaign itself. The Deck of Many Things is not just a wondrous artefact, but very probably, a box/bag—whatever it came in, of chaos.Over the last forty years, The Deck of Many Things has always been part of Dungeons & Dragons, from edition to edition, and in the twenty-first century, there have been numerous attempt to turn The Deck of Many Things from the description in a rulebook into the handout of all handouts—an actual physical Deck of Many Things. Some of them are, like Green Ronin Publishing’sThe Deck of Many Things, have become highly collectible and so surprisingly expensive. Of course, numerous other physical versions of The Deck of Many Things can be found—and for a whole less than what you would pay for a copy of Green Ronin Publishing’s The Deck of Many Things. The latest edition is from Lamentations of the Flame Princess, best known as the publisher of Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay retroclone and its line of associated adventures, but it is not as The Deck of Weird Things.

As an in-game artefact, The Deck of Weird Things is designed to be left in the collection or library of some wizard, the point being that it should be found with some relative ease rather than being secreted away under a mound of treasure in a deep dungeon. It consists of a deck of fifty-two cards, but when found, there will be between two and twenty cards missing, these having been drawn by a previous finder of The Deck of Weird Things. As soon as anyone finds the box or bag containing The Deck of Weird Things, they know what it is, how it works, and that its rules bind all those who find it. These are simple—three or more persons must be present to draw from The Deck of Weird Things, they must all agree to draw, they must agree to draw the same number of cards, and that it must be shuffled before drawing. Then cards are drawn one-by-one, the effects described on each card taking place, and once they have, each card disappears, so further depleting The Deck of Weird Things.

So what effects might happen when a Player Character draws a card? The drawer’s hair—all of it, becomes brittle, inflexible, and like straw; a particularly frail and elderly person becomes obsessed with the drawer and joining the party, and generally though not of any real use, grants a bonus to reaction rolls when present; the drawer’s player must swap their drawer’s highest ability score with the lowest; the drawer can buy one single item or service for free; the drawer is immune to poisons and diseases; once everyone has drawn their cards, the current drawer can choose to draw more just for himself; and suddenly, duplicates appear of those drawing cards, but they do not want to attack their respective drawers, but go and settle down and live an entirely mundane life! There is a huge variety of effects in The Deck of Weird Things, some obviously mechanical, some world related, and so on, and given that each card disappears after having been drawn and taken effect, they are extremely unlikely to see them repeated unless there are multiple copies of The Deck of Weird Things in a game world. Further, given the number of effects in The Deck of Weird Things, its effects are still unlikely to be duplicated even if it turns up in an entirely different campaign.

The Deck of Weird Things requires some preparation before play. For this, two standard decks of playing cards are required. One is used to determine the category, that is, the page to refer to, whilst the other to random determine which of the four possible effects given on the page come into play. As per The Deck of Weird Things, cards are removed from the first deck to reflect cards actually disappearing after being drawn from The Deck of Weird Things.

Essentially, The Deck of Weird Things is a book of—not tables—but of one big table. One big table with what is effectively over two hundred entries. These are divided into categories, one category per page, and four entries per category. These are clearly presented on each page, so that that process from drawing a card to determine the category to drawing a card to determine the specific effect all plays out fairly quickly.

Physically, The Deck of Weird Things is a sturdy, digest-sided book. It is well written and there are nicely done standard deck of playing cards-themed illustrations of Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay signature figures dotted throughout the book. However, the look of the book is pedestrian at best. Not so, the cover, which is a really attractive piece depicting the actual The Deck of Weird Things. The extra slipcover for The Deck of Weird Things is very nice, but entirely optional.

The Deck of Weird Things offers exactly what it promises—a means to change a campaign, to add random effects, to upset the proverbial apple cart, and to add weird effects to campaign. It will do that, and if that is what you as the Game Master want for your campaign and your players are happy with that, then fine, certainly add The Deck of Weird Things to change, potentially really change your campaign. And it should be noted that this does not have to be a campaign just for Lamentations of the Flame Princess Weird Fantasy Roleplay—The Deck of Weird Things will work for any Old School Renaissance retroclone, just as it would work for Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition.

However, there is just one reason why you would not add The Deck of Weird Things to your campaign—and that is price. The Deck of Weird Things was released as a fundraiser and so is correspondingly expensive, and even more expensive with the now-unavailable limited-edition slipcover which goes with it. Notably, even the publisher does not think that this book is worth its purchase price and for its price, you almost wish that The Deck of Weird Things was actually a copy of The Deck of Weird Things and not a book. Such a thing would really work to entice your players and their characters, to tempt them with ultimate power, or ultimate ruin. Such a physical object would be magical in terms of game play, whereas drawing ordinary playing cards and referring to a big table, not so much. To be fair though, The Deck of Weird Things is not a deck of cards and was never intended be a deck of cards. It is though, given its price, more of a collector’s item than an actual supplement you would bring to the table.

October Horror Movie Challenge: Doctor Mordrid (1992)

As typical, I start with some of the left-overs from last-year. This one was high on my list due to some chatter online. I guess the deal is that it was supposed to have been a Doctor Strange movie with Jeffery Combs playing the Strange role. Here he is now Anton Mordrid, and it suits him better I think. Brian Thompson is in this as well, playing, what else, the bad guy.

As typical, I start with some of the left-overs from last-year. This one was high on my list due to some chatter online. I guess the deal is that it was supposed to have been a Doctor Strange movie with Jeffery Combs playing the Strange role. Here he is now Anton Mordrid, and it suits him better I think. Brian Thompson is in this as well, playing, what else, the bad guy.The effects are a little cheesy, but that is to be expected, this was low budget even 1992 standards. It was fun to see some old-school stop-action effects.

The horror is roughly on par with the Doctor Strange comics. All the elements are there, but you are never really expected to be afraid.

Combs and Thompson make for great adversaries, it is a shame we have not seen them in something else together. Both look so damn young in this. But I guess this movie is nearly 30 years old.

The "I'll see ya again I promise," leads me to believe that there was going to be more, but sadly we never got it.

All in all a fun little movie.

Watched: 1

New: 1

NIGHT SHIFT Content

Doctor Mordrid's world is so adaptable to Night Shift that one wonders why I never watched it before this! He is in all respects a version of Doctor Strange, but there is more to it than that. Mordrid, for example, seems to be much older than Strange having waited 150 years for the return of Kabal.

Anton Mordrid, Ph.D.20th Level WarlockStr 12 (+0) Dex 10 (+0) Con 17 (+2) Int 18 (+3)* Wis 18 (+3)** Cha 15 (+1)**XP: 4,000,000Hit Dice: 11d4+18 (20) Hit Points: 66 AC: 7Attack Bonus: +6Check Bonus: +8*/+6**/+4Armor: Magic cloakSaves: +7 vs. spells and magical effectsFate Points: 10Class Abilities: Arcana 150% (knowledge about magic, rituals, cults, and spellcasting), Spellcasting 150% (160% if he has his Amulet of Kronos).Other Special Abilities: Arcane Bond (Amulet of Kronos, adds +10% to spellcasting), Blaster, Enhanced Senses, TelekinesisSpells Levels: 1:6 2:5 3:5 4:5 5:4 6:4 7:4 8:3 9:3

Anton Mordrid, Ph.D.20th Level WarlockStr 12 (+0) Dex 10 (+0) Con 17 (+2) Int 18 (+3)* Wis 18 (+3)** Cha 15 (+1)**XP: 4,000,000Hit Dice: 11d4+18 (20) Hit Points: 66 AC: 7Attack Bonus: +6Check Bonus: +8*/+6**/+4Armor: Magic cloakSaves: +7 vs. spells and magical effectsFate Points: 10Class Abilities: Arcana 150% (knowledge about magic, rituals, cults, and spellcasting), Spellcasting 150% (160% if he has his Amulet of Kronos).Other Special Abilities: Arcane Bond (Amulet of Kronos, adds +10% to spellcasting), Blaster, Enhanced Senses, TelekinesisSpells Levels: 1:6 2:5 3:5 4:5 5:4 6:4 7:4 8:3 9:3Mordrid has an extensive library so all spells in the core NIGHT SHIFT book are available to him