Feed aggregator

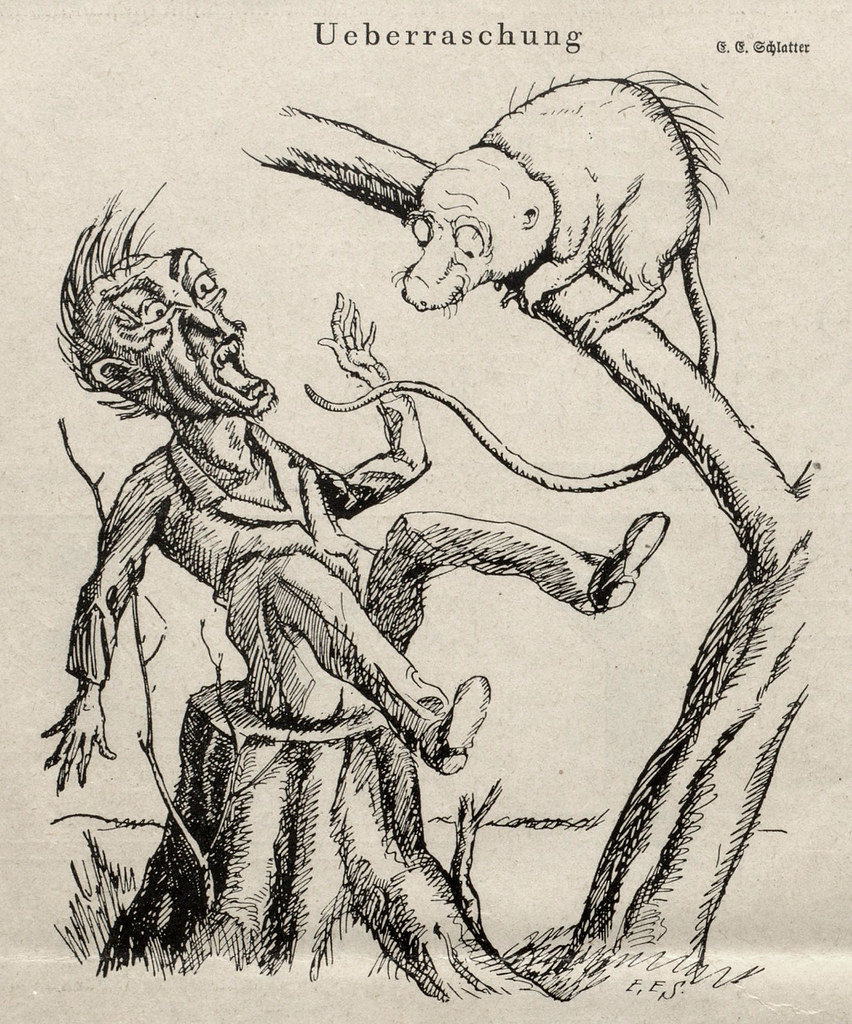

Ernst Emil Schlatter (1883 - 1954)

The Great Horror - Nebelspalter, 1924

The Great Horror - Nebelspalter, 1924

The New Teachings - Nebelspalter, 1922

The New Teachings - Nebelspalter, 1922

Message From Far Away - Nebelspalter, 1922

Message From Far Away - Nebelspalter, 1922

Education - Nebelspalter, 1923

Education - Nebelspalter, 1923

The Frightened - Nebelspalter, 1920's

The Frightened - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Court Session - Nebelspalter, 1924

Court Session - Nebelspalter, 1924

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1923

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1923

Internalized Walk - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Internalized Walk - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Pursuit - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Pursuit - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Indoctrination - Nebelspalter, 1923

Indoctrination - Nebelspalter, 1923

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1924

Admonition - Nebelspalter, 1924

Penitential Sermon - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Penitential Sermon - Nebelspalter, 1920's

Artworks originally published in Swiss humor magazine "Nebelspalter" from the 1920's.

DMSGuild Witch Project: The Hedgewitch

Let's start this off with two products that are used in conjunction.

Let's start this off with two products that are used in conjunction.As a reminder the "rules" for reviews are here, http://theotherside.timsbrannan.com/2020/10/the-dmsguild-witch-project.html

The Hedgewitch (player class) by PCSpinner and Covens (for the Hedgewitch) by PCSpinner

Both products feature the same cover art with some color variation.

The Hedgewitch PDF is a PWYW with a suggestion of $1.00 for 9 pages.

Covens is $0.50 for 4 pages.

It looks like the math here is about ¢10 a page. Let's see if that holds up across the DMSGuild titles.

Both come in standard format and printer-friendly format.

The Hedgewitch is true to its name and presents a Hedgewitch class. She gets spell levels up to level 5 only. The class has a nice variety of features and powers and all have a really nice witchy feel to them.

The "sub-classes" or archetypes of the hedgewitch are "covens" which is exactly what I would do and would expect since "Traditions" were taken by the Wizards class. There is a nic variety here.

The layout and art look really nice. I think some of it is public domain art and photos. At least they look a little familiar.

There are no "new" spells, but it does use spells that were new at the time of publication.

Covens for the Hedgewitch is similar in terms of art, layout, and options. This pdf offers another four covens to use with the Hedgewitch.

So a couple of thoughts.

These easily could have been combined into one product, but I think I see the rationale for keeping them separate. Either way it is fine.

The layout and art is really nice, the creator spent some time on this and it shows. This was released four years ago and I thought the creator would have done more, but I only see six total titles in the DMSGuild. The inclusion of printer-friendly versions is a very nice touch.

I would try this class out. I think there are some good ideas here.

ETA: The Hedge witch class was taken down since I wrote this review.

The DMSGuild Witch Project

October is here! I am not sure about you, but my thoughts have turned to Halloween. Ok, that’s not true. I was thinking about Halloween back in August. But since most everyone else is now thinking about Halloween I thought it might be nice to delve into reviews.

October is here! I am not sure about you, but my thoughts have turned to Halloween. Ok, that’s not true. I was thinking about Halloween back in August. But since most everyone else is now thinking about Halloween I thought it might be nice to delve into reviews.My kids have been wanting me to create a 5e Witch class ever since 5e came out. I have not done it because, well, I think I can get out of the warlock and druid and some deft multiclassing the witch character I want. Presently I am playing a wizard who also has the magical scholar background that is working out well. I am also playing multiclass warlock/paladin to cover a “Green Knight” and Warlock that has been picking up various feats from sorcerer, wizard, and bard to get a more witchy feel. But since I play so rarely (I am always the DM) it is hard for me to get out of these characters what I want. Plus I feel the need to playtest everything.

So with Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything on the near horizon, I have turned to the DMSGuild for ideas.

There are so many witch classes on the DMSGuild I figure I would try a few. And I have. And my experiences...well...let’s just say they have been all over the place.

Now, I am planning to review these witch classes and witch related materials. BUT I want to set some ground rules for myself.

The Rules

I normally feel a little bad when reviewing someone else’s witch class. Not to be too blunt, but there is just no way they have been writing about this as long as I have. So I can’t knock them down for missing something that is obvious to me, but maybe not to someone else.

Also, I have to remember that these publications, by their very nature, are amateur. I can’t expect high levels of layout, art, or design in most of these. Yes, there is some absolutely stunning pdfs there in terms of production values and art. But most of these are not going to be at that level; most of the books there are not at that level period.

In truth, art is going to be a big issue since a lot of the PDFs I have grabbed seem to have a lot of “borrowed” art. I’ll mention art issues as they come up.

The price point also seems to be an issue. A lot of these products are priced much higher than similar-sized ones on DriveThruRPG. Like the art, I’ll talk about the price if it is a big issue for the item. My mental comparison on price here is going to be about ¢10 per page.

I want to give each product a fair shot, given that I know that many of these could be the first effort of the author/designers.

Some products I’ll be reviewing here are quite small. Others are linked to other products. Some others still are naturally paired with other products. In any case, I have bought and downloaded enough to cover the entire month.

I am going to leave this page like this with the rules and what I am doing so I can link back to it with each review.

With each class/pdf I am going to be looking for the following:

- Is it a playable class?

- What new things does it offer?

- How “Witchy” is it?

- Are there any new powers, feats, or spells?

My goal is to find something to recommend for each product and no to unfairly compare it to other, more polished witch products.

I might also make a distinction between a "witch" and a "Witch" or class that can act like a witch vs a class named Witch. This is a distinction that might only matter to me, but hey, this is my blog.

Happy October! From the Other Side!

It is now October!

Larina by Djinn

Larina by DjinnLet's celebrate the most wonderful time of the year at The Other Side!

October Horror Movie Challenge: Getting Ready

This year lacks a real theme save for "movies I have had laying around forever and I need to watch them or sell back the DVDs" and "movies I have been meaning to watch forever".

I am going to lean heavily on my preferred time of the late-60s to mid-70s. And I have more than a few Italian horror films.

I have about 110 movies here. Some I have already seen so won't do those. There are also more than a few overlaps. I'll try to hit more than one per day, but often that is not really doable. I'll also hit more over the weekends.

I am going to also try to include as much NIGHT SHIFT content as I can.

Let's see where I end up at the end of the next month!

Review: Pages from the Mages

As I mentioned earlier, The Pages from the Mages feature of Dragon Magazine was one of my favorite features and I looked forward to seeing what new spells Ed Greenwood would relay from the great sage Elminster. I was very pleased when I saw that the entire collection was pulled together into a single tome. The original Pages from the Mages spaned roughly 10 years from 1982 to 1992 and both editions of AD&D.

As I mentioned earlier, The Pages from the Mages feature of Dragon Magazine was one of my favorite features and I looked forward to seeing what new spells Ed Greenwood would relay from the great sage Elminster. I was very pleased when I saw that the entire collection was pulled together into a single tome. The original Pages from the Mages spaned roughly 10 years from 1982 to 1992 and both editions of AD&D. For this review, I am considering both the original print version sold by TSR and the PDF version sold through DriveThruRPG. Presently there is no Print on Demand option.

The book is 128 pages. Color covers, black & white interior art with full color, full-page art. Designed for the AD&D 2nd Edition game.

The PDF sells for $9.99 on DriveThruRPG.

The softcover book originally sold for $15.00 in 1995.

This book covers some 40 or so unique spell books from various spellcasters from the Forgotten Realms. Some of these spellcasters are well known such as Elminster and others less so or at least nearly mythic in the Realms. This is one of the book's greatest strengths. While this could have been just a collection of books with known spells, it is the stories and the myths behind the books that make this more.

While many of the spells found within these books are fairly well known, there are plenty of brand new and unique spells. This is what attracted me to the original Dragon magazine series. Within these pages, there are 180 or so "new" spells. I say new in quotes because most, if not all, these spells appeared first in the pages of Dragon magazine and then again in the pages of the hardcover Forgotten Realms Adventures for 2nd Edition.

Additionally, there are a number of new magic items and even a couple of new creatures.

The true value for me, as a DM and a player, is to provide these new spell books as potential treasure items or quest items. Even saying the name of some of these books, like Aubayreer's Workbook, is enough to get my creative juices flowing. Where is it? Where has it been? What other secrets does it contain?

I often refer to a product as punching above its weight class. This is one of those books. While overtly designed for the 2nd Edition game there is nothing here that can't be used with any version of the D&D game, from Basic all the way to 5th edition with only the slightest bit of editing needed.

While I have a print copy and the PDF, a Print on Demand version would be fantastic.

A complete list of the spells, spellbook, creatures and characters in this book can be found on the Forgotten Realms wiki, https://forgottenrealms.fandom.com/wiki/Pages_from_the_Mages

This Old Dragon: Retrospective, Pages from the Mages

Another This Old Dragon Retrospective today. Today I want to cover one of my favorite series in the run of Dragon, and one that had far fewer entries than I thought, Pages from the Mages. Again this series is by Ed Greenwood writing to us as Elminster. It's a wonder I wasn't a fan of the Realms until pretty much 2001.

The premise is laid out in the first installment, Elminster (or Ed, sometimes it is hard to say) wondering aloud why we don't find more unique spell-books in treasure hordes. He goes on to explain that such tomes are very rare. The set up is solid and less in-universe than The Wizard's Three. But like The Wizard's Three, this is used to give us some new spells and some magic tomes worthy to build an adventure around. So let's join Ed and Elminster and pour through these pages of a nearly as legendary tome, Dragon Magazine, and see what treasures we can find.

Pages from the Mages

Our first entry is in Dragon #62 which has one of my all-time favorite covers; the paladin on horseback challenging three orcs. This takes us all the way back to June 1982, the height of my D&D Basic/Expert days. The magic books we discover here are:

Mhzentul’s Runes, with details for making a Ring of Spell Storing. Rings that become guardian creatures (but no details) and the spells Fireball, Fire Shield, Fire Trap, and Delayed Blast Fire Ball.

Nchaser’s Eiyromancia, this book gives us two new spells, Nulathoe’s Ninemen and Nchaser’s Glowing Globe.

Book of the Silver Talon, this sought after tome has a number of good spells, Read Magic, Burning Hands, Comprehend Languages, Detect Magic, Erase, Write, Identify, Message, Shocking Grasp, Shield, Darkness 15’ Radius, Detect Invisibility, Knock, Ray of Enfeeblement, Web, Wizard Lock, Blink, Dispel Magic, Gust of Wind, Infravision, Phantasmal Force, and Protection From Normal Missiles. Additionally, it has recipes for the ink for Read Magic, Buring Hands, Comprehend Languages, Detect Magic, Erase, Write, Identify, Message, Shocking Grasp, and Shield. All in-universe and fluff, but fun all the same AND an often overlooked aspect of magic.

Chambeeleon, the unique spellbook is described as a treasure. In contains the spells, Water Breathing, Fly, Lightning Bolt, Fire Shield (cold flame version only), Ice Storm, Airy Water, Cone of Cold, Conjure Elemental (new version), Disintegrate, Glassee, Part Water, Spiritwrack, Cacodemon, Drawmij’s Instant Summons, Reverse Gravity, and Vanish. Which leads to the obvious conclusion that Drawmij was also moving between the planes between Greyhawk and the Realms. This book is also considered to be a religious text by many priesthoods of aquatic gods. In each case, we also get a little history and the last known or suspected whereabouts of the tomes. I say tomes, but thankfully Ed was not so limited in his thinking. Some are books, some are collections of pages and others are stranger still. I find it interesting that this entry is followed by the classic NPC class, the Scribe, also by Ed.

More Pages from the Mages

Our next entry comes from Dragon #69 which I also covered as part of my This Old Dragon Issue #69. Again a fantastic cover from the legendary Clyde Caldwell. The article is titled "More Pages from the Mages" and has art by Jim Holloway. Interestingly there is a book in the art named "Holloway's Guide to Everything" could that be the next 5e book to come out? The actual books covered here are:

The Magister, this particular tome has no title so it is just called "the Magister". It consists of 16 sheets of parchment between two ivory covers. It includes a treatise on illusion magic and the spells Change Self, Color Spray, Phantasmal Force, Detect Illusion, Mirror Image, Dispel Illusion, Nondetection, Massmorph, Shadow Door, Programmed Illusion, and True Sight. There is also an alternate version of the Clone spell. There is also a lot of debate on what is exactly on the last page.

Seven Fingers (The Life of Thorstag), this tome is bound in leather. It describes the Void Card from the Deck of Many things. How wonderfully random! Yet so on point for an academically minded wizard. There is also a recipe for Keoghtom’s Ointment, which may or may not be correct. There is also some local history.

The Nathlum, is a rather non-descript book. But there is some saying about books and covers. This one will cause damage to anyone of Good alignment holding it! It includes recipes for poisons, so not all these books are limited to spells. Something that honestly is not stressed enough.

The Workbook, there is no accurate description of this tome. So Elminster isn't all-knowing (ok to be fair, Elminster and Ed would be the first to point this out). This is rumored to include the spells Spendelarde’s Chaser, Caligarde’s Claw, Tulrun’s Tracer, Tasirin’s Haunted Sleep, Laeral’s Dancing Dweomer, Archveult’s Skybolt, and Dismind. All are new.

As I mentioned in my original post, back in the day I would go right for the spells, today I am more interested in the story behind the spellbooks. Maybe the spells inside are some I have already seen, but that is not what makes it valuable to me now. It's the story, the history, maybe there is something really special about this book. Maybe the spellcaster is still alive. Maybe his/her enemies are and want this book. My cup runneth over with ideas.

Pages From the Mages III

We jump to December 1984 and Dragon #92. Damn. Another classic cover. This time it is "Bridge of Sorrows" by Denis Beauvais and he has updated it on his website. what a great time to be a classic D&D fan. This one is very special for me for many reasons. First, this was the very first PftM I had ever read. I didn't know a damn thing about the Realms (and I only know slightly more now) but as I mentioned in my This Old Dragon Issue #92 I remember going on a quest to recover Aubayreer's Workbook having only the glyph as a clue. I don't remember all the details save that the quest was dangerous and the spells in the book were a bit anti-climatic given the quest. Not that the spells are bad (hardly!) it is the quest was that hard.

This is also, at least from what I can tell, our very first mention of The Simbul, "the shapeshifting Mage-Queen". I guess she is looking for a copy of this book too! I think I see a plot hook for my next Realms game (and playing on the events in The Simbul's gift). MAYBE that quest was only half of the tale! Maybe the other half was really to get this book to The Simbul. I am only 30+ years late. Thank you Ed! Of course, that is only one of FOUR magic books. Let's have a look.

Aubayreer's Workbook, this "book" is a long strip of bark folded accordion-style between two pieces of wood with a rune carved on it. The spells are read magic, burning hands, dancing lights, enlarge, identify, light, message, write, ESP, wizard lock, dispel magic, explosive runes, fireball, and extension I. There three special spells hailcone (a version of ice storm), and two new spells, Aubayreer's phase trap and thunderlance.

Orjalun's Arbatel, not to be overshadowed this book's pages are beaten and polished mithril! Lots of Realms-centric details here. In fact this might be where many of these topics saw print for the very first time. This one includes two new spells Encrypt and Secure.

The Scalamagdrion, bound in the hide of some unknown creature this book has a little surprise. The spells included are (and in this order): Write, erase, tongues, message, unseen servant, wizard lock, identify, enchant an item, permanency, blink, disintegration, feeblemind, fly, death spell, flame arrow, delayed blast fireball, invisibility, levitate, conjure elemental, minor globe of invulnerability, wall of force, remove curse, and dispel magic. The book also has a unique monster bound up in the pages that will protect the book!

The Tome of the Covenant, named for the group of four mages that gathered together to stop the onslaught of orc from the north. What this entry makes obvious is exactly how much detail Ed had already put into the Realms. There are four new spells in this book, named for each one of the Covenant wizards. Grimwald's Greymantle, Agannazar's Scorcher, Illykur's Mantle, and the one that REALLY pissed me off, Presper's Moonbow. It pissed me off because I had written a Moonbow spell myself. Only mine was clerical and it was a spell given by Artemis/Diana to her clerics. My DM at the time told me it was too powerful at 5th level and here comes Ed with a similar spell, similarly named and his was 4th level! Back then it was known as "Luna's Moonbow" named after one of my earliest characters. Ah well. Great minds I guess.

Pages from the Mages IV

We jump ahead to Dragon #97from May 1985. I also covered this one in This Old Dragon Issue #97. Rereading this article years later is the one where I thought I should stop being such a spoiled Greyhawk twat and see what the Realms had to offer. It would still be a long time before I'd actually do that. This one also had a bit of a feel of the Wizard's Three to it. The books covered here were:

Bowgentle's Book, a slim volume bound in black leather. It has a ton of spells in it, so many I wonder how "slim" it actually was. Cantrips clean, dry, and bluelight, and the spells affect normal fires, hold portal, identify mending, push, read magic, sleep, continual light, darkness 15' radius, detect evil, detect invisibility, ESP forget, knock, levitate, locate object, magic mouth, rope trick, strength, wizard lock, blink, dispel magic, fireball, fly, hold person, infravision, Leomund's Tiny Hut, lightning bolt, protection from evil 10' radius, protection from normal missiles, slow, tongues, water breathing, charm monster, confusion, dimension door, enchanted weapon, fire shield (both versions), minor globe of invulnerability, polymorph other, polymorph self, remove curse, wizard eye, Bigby's Interposing Hand, cone of cold, hold monster, passwall, and wall of force. The two new spells are dispel silence and Bowgengle's Fleeting Journey.

The Spellbook of Daimos, this one has no title on the cover and described as very fine. Very little is known about who or what "Daimos" is. The spells included are, identify, magic missile, invisibility, levitate, web, fireball, monster summoning I (a variant), slow, suggestion, confusion, fear, fire trap, polymorph self animate dead, cloudkill, feeblemind, anti-magic shell, disintegrate, geas, globe of invulnerability, reincarnation, repulsion, Bigby's Grasping Hand, duo-dimension, power word stun, vanish, incendiary cloud, mind blank, astral spell, gate, and imprisonment. The new spells are flame shroud, watchware, and great shout.

Book of Num "the Mad", this one is interesting. It is loose pages held in place by two pieces of wood and a cord. Num was a reclusive hermit who learned a bit of druidic lore. There are a few more spells here. But what is more interesting are the new ones. Briartangle, Thorn spray, and Death chariot.

Briel's Book of Shadows. Ok, the title has my attention. Though it has little to do with the Books of Shadows I am most often familiar with. This one has the following new spell, Scatterspray. It does have some details on uses of Unicorn horns and a recipe for a Homonculous.

These books really upped the number of spells included in each book. Was this intentional? Is this the "Power creep" that was starting to enter the game at this point? It was 1985 and this was not an uncommon question to ask with the Unearthed Arcana now out (and now these spellbooks all have cantrips!) and classes like the Barbarian and Cavalier making people say "D&D is broken!" The more things change I guess...

Pages from the Mages V

Dragon #100 from august 1985 was a great issue all around. From the Gord story, to Dragon Chess, to this. I really need to give it a proper This Old Dragon one day. But until then Ed is back with some more magic. Sabirine's Specular, the first book from a wizardess. It has a good collection of standard spells. The new spells are Spell Engine, Catfeet, Snatch, Spark (Cantrip), Bladethirst, and Merald's Murderous Mist. Glanvyl's Workbook, what is neat about this book is it appears to be the book of a lesser magic-user and these are his notes. So like the workbook a student might have in a writing class. There are three new cantrips, Horn, Listen, and Scorch. One new spell, Smoke ghost, which is level 4 so he had to be at least high enough level for that. and the preparations for inks for the Haste and Lightning Bolt spell. The Red Book of War, this is a prayer book for clerics of the war god Tempus. I liked seeing that spells for clerics were also offered. These of course would differ from the arcane counterparts in many ways, or, at least they should. Ed makes the effort here to show they do differ and that is nice. Many often forget this. There are a number of prayers here that are common. Also the new prayers/spells are Holy Flail, Reveal, Bladebless, and Sacred Link, one I enjoyed using back then. None of these spells though would late make it to the AD&D 2nd published version of Pages from the Mages. The Alcaister, this is a book with a curse. Not the spell, but rather a poison worked into the pages that is still potent 600 years after it was written. Among the common spells it has three new cantrips, Cut, Gallop, and Sting. There is one new spell, Body Sympathy, and the last page of the spellbook is a gate! Destination determined at random.

Arcane Lore. Pages From the Mages, part VI

It is going to be a five-year jump and new edition until the next Pages comes in Dragon #164. The article has some subtle and overt changes. First there is a little more of the "in character" Elminster here. Ed has had more time to write as the Elminster and I think this is part of the success of the novels. The overt change is now the spells are in AD&D 2nd Edition format. Not too difficult to convert back (or even to any other edition) but it is noticed. It is December 1990, lets see what Ed and Elminster have for us. Book of Shangalar the Black, a deeply paranoid wizard from 700 years ago you say? I am sure this will be fun! There are only new spells in this short (4 page) spellbook. Bone Javelin, Negative Plane Protection, Repel Undead, and Bone Blade. Well, the guy had a theme to be sure. The Glandar's Grimoire, now here is something else that is rarely done, at least in print. This book is only a burnt remnant. What is left of what is believed to be a much larger tome is four pages with new spells. Fellblade, Melisander's Harp, Disruption, and Immunity to Undeath. The Tome of the Wyvernwater Circle, this is a druids prayer book. Now I know D&D druids are not historical druids that did not write anything down. So a "Druid book" still sounds odd to me. But hey when in the Realms! This book has a few common spells and some new ones; Wailing Wind, Touchsickle, Flame Shield, and Mold Touch. The Hand of Helm, another clerical prayer book. This one is of unknown origin. It has 27 pages (and thus 27 spells; one spell per page in 2e), four of which are new; Exaltation, Forceward, Mace of Odo, and Seeking Sword.

Is it because I know TSR had gone through some very radical changes between 1985 and 1990 that I think the tone of this article is different than the one in #100? I can say that one thing for certain is that Ed Greenwood is more of a master of his craft here. The history of the Realms is, for lack of a better word, thicker in these entries. There is more background to the spellbooks and their place in Realms lore. This is a positive thing in my mind in terms of writing. It did make it hard to add them to my Greyhawk campaign, but by 1990 I was hard-core Ravenloft; shit just randomly popped out of the Mists all the time. If I needed one of these books I could make an excuse to get them there.

Pages From the Mages

It is now May 1992. I am getting ready to graduate from University now and Dragon #181 is giving us our last Pages from the Mages. It has been a fun trip. A little bit of framing dialogue starts us off. I did notice we have gone from talking about "the Realms" to now saying "FORGOTTEN REALMS® setting" instead.

Galadaster's Orizon. This book is actually considered to be a "lesser work" in the eyes of the wizard-turned-lich Galadaster, but this is all that survived of his tower's destruction. Among the common spells there are three new ones. Firestaff, Geirdorn's Grappling Grasp, and Morgannaver's Sting. Arcanabula of Jume, another book from a wizardess (rare in this collection of books). This one is written in the secret language of Illusionists (which are, as a class, slightly different in 2nd Ed) and is a traveling spellbook. It has four new spells, Dark Mirror, Shadow Hand, Prismatic Eye, and Shadow Gauntlet. Laeral's Libram. I was just about to comment that while these books are fantastic, none of the names have the recognition factor of say a Tenser, Bigby, or even Melf. Then along last comes Laeral. Now here is someone famous enough that I have box of her dice sitting next me! Laeral Silverhand is of course one of the famous Seven Sisters. So not just a name, but a Name. This spellbook has the common spells of feather fall, magic missile, spider climb, and forcewave. As well as the new spells of Laeral's Aqueous Column, Jhanifer's Deliquescence, and Blackstaff. The blackstaff spell was created by another Name, Khelben Arunsun. This one would be worthy of a quest to be sure. Tasso's Arcanabula. Our last spellbook comes from an illusionist named Tasso. Tasso is almost a "Name." I recognize it, but I am not sure if it was because of this article or some other Realms book I read. The spell book has what I consider to be the common illusionist spells and four new ones. Tasso's Shriek, Shadow Bolt, Shadow Skeleton, and Prismatic Blade. That's where I have heard of him. I have used that Prismatic Blade spell before,

After this series, the Wizard's Three took over as our source of spells from Ed.

I have read that Ed created this series based on his love of some of the named spells in the AD&D Player's Handbook. He wanted to know more about the characters and how they came to be associated with those spells. I think that he showed his love here in this series. I also think it was made clear that sometimes the spell creator's name gets added to a spell not just by the creator, but by those who chronicle the spell, spellbook, or spellcaster later. Sometimes centuries later.

We got away from this but now it looks like it is coming back. especially with the recent Mordenkainen, Xanathur, and now Tasha books coming out from WotC.

Dungeons & Dragons Animated Series: Requiem The Final Episode

Well here is an unexpected treat.

Growing up I didn't watch much of the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon. I caught it when I could, but I worked most Saturdays and didn't always see it. This was also back before DVRs or even on-demand viewing, so unless recorded it on VHS, well I missed out.

Many years later I picked it up on DVD when it was packaged with some wonderful 3rd Edition content. This was about the same time my oldest was getting interested in D&D and the D&D animated series was the perfect gateway drug for him. If it is possible to wear out a DVD then he would have done it.

On the DVD extras were a lot of neat little things. One of them was the script for Requiem, the last episode of the series. Written by series writer Michael Reeves it detailed the last adventure of Hank, Eric, Diana, Bobby, Sheila and Uni. It had been put on as a radio play in 2006 and was also included in the DVD release.

Now some enterprising animators pulled together clips from the series and new animations to give us the final episode in full animated form.

Watch it while you can.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QsNHTnY6HQg

I think they did a pretty good job, to be honest, all things considered.

The Aftermath: NARBC Arlington September 2020 – 3

The Aftermath: NARBC Arlington September 2020 – 2

New Page: Appendix O and the Purpose of Research

So I am calling it Appendix O.

Just a small portion of my library.

Just a small portion of my library.If you are interested in seeing the sites on the web that I found useful or have good witch content then check out my other page Witch Links.

If you want to know what movies I have been influenced by to write witch, vampire, and other horror-related content then check out my October Horror Movie Challange.

And occasionally I do make an Appendix N post.

Nothing in the citations will tell you how to play a better game of D&D, Ghosts of Albion, NIGHT SHIFT, or any other RPG.

Nor will they allow you rebuild one of my books or classes from just the content they have. They all however have lead me to a place where those books could be written.

Current research pile.

Current research pile.Also, this is not scholarly-level research here. I did not come up with a thesis statement, a research question, or anything like that and then carried out a systematic literature review. This is 100% books that were within my grasp at the time (eg growing up in a small midwest town with a larger than average personal and public libraries), then access to one of the largest open shelve university libraries in the state, and of course then the internet. These are titles that captured my attention at the time and then left a mark on my RPG writing.

As with all my Pages here, I'll update this one periodically. In fact looking at the pictures above I see there are a few entries that I missed.

The Purpose of Research

Back when I was getting my Ph.D. in Ed. Psych my advisor was going over my records and my Master's Thesis and asked me why I did not go into Cognitive Psychology, which is what my academic life had been up to that point. I told him I was (and am) more interested in how people learn. We talked about my Master's Thesis where I showed that it takes about 550 ms to activate a memory from long-term memory when it had been properly primed by a queue. It was situated in the current Information Processing theories of the time. My advisor, who was one of the nicest people you could ever meet, looked at me and said "so what?" I was floored. So what? I spent months working on that theory, and then more weeks writing the software to test it, weeks testing undergrads, weeks of eating nothing but popcorn and pineapple while writing a 180-page thesis. So what?? And, he was right. I was in an Ed. Psych program now, not Cog Psych. My research had to mean something. If I could not tell that Fourth Grade teacher at CPS what my research meant to her then why should I do it?

This page came about not because I kept getting asked for it. That is true and a good enough reason, but the real reason is I am constantly going back and re-examining my own work and research.

I love to research for research's sake. But that is not the degree I ended up with. Research is fun, but it needs a goal. Appendix O started out without a goal in mind. But that doesn't mean I can't have one now.

Presently I am working on two books for my "Basic-era Games" banner; "The Basic Bestiary" and "The High Witchcraft" books. I wanted at least one of these to be ready by Halloween. That's not going to happen. The Basic Bestiary is moving along well, but not as fast as I would like. High Witchcraft...that's another matter.

I have been calling High Witchcraft my last book on Witches. I want that to mean something. But I think I am setting up too many mental roadblocks for myself. So I am going back to my first assumptions. Back to my first "research questions" as it were. It might take me a little longer, but I want something really good. Something that is worthy of being called my "last witch book."

Basic Bestiary is moving along fine. I have a ton of material, I just need to edit it.

The Secret Order is a call back to the witches of Dragon Magazine (but not setting them up the same way, I gotta do my own thing) and to that very strange time between 1981 and 1983 when we freely mixed in both Basic and Advanced D&D concepts. I am publishing it with my "Basic-Era Compatible" logo as opposed to "Labyrinth Lord" or "Old-School Essentials" (and either of those would be fine) because I do want a lot more freedom to express my witch how I want.

For the cover art, I am a huge fan of the Pre-Raphaelites. So there was really only one choice for the high Witchcraft book and that was "Astarte Syriaca" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Astarte was one of the Goddesses I researched the most in those early days of my first witch. I even made my first version of Larina a worshipper of Astarte, and not the more obvious Hecate.

For the Basic Bestiary I wanted a Pre-Raphaelite, but "The Nightmare" by Henry Fuseli was calling to me. I always loved that painting.

Back to the books!

The Aftermath: NARBC Arlington September 2020 – 1

The Aftermath: NARBC Arlington September 2020 – Introduction

1980: Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age

1974 is an important year for the gaming hobby. It is the year that Dungeons & Dragons was introduced, the original RPG from which all other RPGs would ultimately be derived and the original RPG from which so many computer games would draw for their inspiration. It is fitting that the current owner of the game, Wizards of the Coast, released the new version, Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition, in the year of the game’s fortieth anniversary. To celebrate this, Reviews from R’lyeh will be running a series of reviews from the hobby’s anniversary years, thus there will be reviews from 1974, from 1984, from 1994, and from 2004—the thirtieth, twentieth, and tenth anniversaries of the titles. These will be retrospectives, in each case an opportunity to re-appraise interesting titles and true classics decades on from the year of their original release.

—oOo—

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was published by Fantasy Games Unlimited in 1980 and has the distinction of being the first roleplaying game set in the Ancient World. It is a roleplaying game in which heroes of the age adventure, travel the known world and sail the Aegean Sea and beyond, battle heroes from other lands, and maybe face the monsters that lurk in the seas and caves far from civilisation. It is also a man-to-man combat system, a trireme-to-trireme combat system, a guide to a combination of Greece in the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, and all that packed into thirty-two pages. However, it is very much a roleplaying of its time and vintage—and what that means is there is at best a brevity to game, a focus on combat over other activities, and a lack of background to the setting. Now of course, many of the gamers who would have played Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age in the early nineteen eighties—just as they are today—would have been knowledgeable about the Greek Myths and so been able to flesh out some of the background. However, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age still leaves the Moderator—as the Game Master is known in Odysseus—with a lot of work to do.

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was published by Fantasy Games Unlimited in 1980 and has the distinction of being the first roleplaying game set in the Ancient World. It is a roleplaying game in which heroes of the age adventure, travel the known world and sail the Aegean Sea and beyond, battle heroes from other lands, and maybe face the monsters that lurk in the seas and caves far from civilisation. It is also a man-to-man combat system, a trireme-to-trireme combat system, a guide to a combination of Greece in the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, and all that packed into thirty-two pages. However, it is very much a roleplaying of its time and vintage—and what that means is there is at best a brevity to game, a focus on combat over other activities, and a lack of background to the setting. Now of course, many of the gamers who would have played Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age in the early nineteen eighties—just as they are today—would have been knowledgeable about the Greek Myths and so been able to flesh out some of the background. However, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age still leaves the Moderator—as the Game Master is known in Odysseus—with a lot of work to do.A hero in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age—and it is very much a case of it being a hero rather than a hero or a heroine, is a young warrior ready to set out on a life of adventure and myth building. Aged between seventeen and twenty-three, he is defined by his home province, which also determines his patron god, his lineage, which determines his primary profession—which he shares with father, and his other skills. Rolls are also made for his family and the armour he begins play with. Notably, a hero has the one skill or ability—his Fighting Skill Number or FSN, initially rated between eleven and twenty, and can go higher. As well as Fighting Skill Number, a player also rolls for his hero’s armour—type, what it covers, and its composition. Heroes with a high FSN are likely to have better, even iron, armour.

Alastair

Age: 23

Home Province: Messenia

Patron God: Hephaestus

FSN: 20

Skills: Accountant (Major), Barber, Architect

Family: Only son, father deceased

Armour: Type II Body Armour (bronze torso and shoulders, greaves, and aspis)

Arms: Shortsword, spear, bow & twenty arrows

So character generation out of the way—although as we shall see, it is not complete—Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age dives not into the mechanics of a skill system (there is none) or the man-to-man ‘combats’ system (as it is described), but the rules for ship-to-ship combat. They describe Greek naval warfare as complex and are essentially a miniatures combat system, for which it is suggested that a large floor space and miniatures are needed. The rules cover movement—by sail and by oars, as well as the effect of the wind, maneuvering, missile fire—from both arrows and spears, collisions and ramming, plus grappling and boarding, taking on water, mast damage, and more. All of this is done in the captain’s orders, which are written down at the beginning of every combat round. The rules cover everything in just three pages.

Man-to-man combat or ‘Combats’ as Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age describes it, is actually more complex than ship-to-ship combat. Initiative is generally handled by weapon range—weapons with longer range or reach indicating that a warrior attacks first. Then each combatant selects two cards, one an Attack Position Card, the other a Defence Position Card. The Attack Position Card indicates where the attacking warrior intends to strike, for example Head, Abdomen, or Calf, whilst the Defence Position indicates where the defending warrior wants to protect, for example, ‘Parry Middle Without Shield’ or ‘Punch with Shield High’. The chosen Attack Position Card and Defence Position Card are cross referenced on the ‘ATK POS/DEF POS’ table. This can generate an ’NE’ or ‘No Effect’ result, in which case the attack is blocked or the attacker missed, or it can generate a modifier which is applied to the chance to hit number. This is determined by cross referencing the weapon used in the attack against the protection value of the armour on the location struck. This is a percentage value under which the attacking player must roll to succeed. Conversely, the player needs to roll high on the percentage dice to determine how much damage is inflicted, which determined by the Attack Position—as determined by the Attack Position Card cross referenced with the roll, the result varying from ‘No Effect’, ‘Stun’, and one or more Wounds to ‘Kneeling’, ‘Unconscious’, and ‘Kill’.

So the question is, where does a warrior’s Fighting Skill Number come into this if it is not being used to determine whether or not he successfully attacks or defends? Well, it does two things. First, it acts as a warrior’s Hit Points, with points being deducted equal to the number of Wounds suffered. Second, for each five points or part of, a warrior’s Fighting Skill Number is ten or above, he gains an extra attack each round. So between ten and fourteen points, a warrior has two attacks, three attacks for between fifteen and nineteen, and four attacks for twenty and above. When a warrior suffers Wounds and his Fighting Skill Number is reduced, if drops past the threshold, so does his number of attacks per round. Although a Warrior’s Fighting Skill Number can rise above twenty by being a successful combatant, the maximum number of attacks he can make is four. Thus points in Fighting Skill Number above twenty four represent just his Hit Points.

Beyond the mechanics for ship-to-ship combat and man-to-man combats, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age includes some campaign notes for the Moderator, primarily movement and encounters—by land and by sea, and done daily. The encounter table includes some classic mythic creatures like Gorgons and Centaurs, but essentially, they have no more stats than Player Character. All of the encounters are accorded thumbnail descriptions, as are the gods. The only major piece of advice for the Moderator is how to handle warrior versus god combat, that comes down to allowing it, but inflicting a high degree of bad luck upon the warrior for being so presumptuous!

There are two other mechanics in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age and both concern the Player Characters, but both are secret. In fact, they are so secret that the Moderator rolls them and never reveals them to his players. Both are straight percentage values. One is the Deity Empathy Score, which reflects how much a warrior’s patron likes or dislikes him, whilst the other is the warrior’s Luck Number. The only suggested use for this is determining how well other people react to the warrior.

In terms of background, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is very lightly written, its treatment of the Homeric Age very broad. Oddly, warriors cannot be from Crete or Troy, the choice of weapons is limited, and there is very little historicity to the whole affair. There are also some oddities in Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age. The first is that the example of play appears on the book’s last page. The second is that in the middle of rules there is a quiz about the rules. Which is very probably unique in the history of the hobby. The third is that given its vintage, it is surprising that Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age does not explain what roleplaying is, but that it does not explain what a Moderator really does either.

Physically, Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is a slim book with rather underwhelming production values. Although the pen and ink illustrations are really quite good, the maps are bland and lack detail. It needs another edit and it is not quite sure what the title is—Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age, Odysseus the Wanderer, or Odysseus Legendry & Mythology (sic). The main issue perhaps is the odd organisation which dives in ship-to-ship combat before personal combat, in the inclusion of a pop quiz about the rules rather than more examples of play, and so on. The game includes a card insert which is intended to be removed and used in play, and includes the Attack Position Cards and Defence Position Cards, and two ship’s deckplans.

—oOo—

Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age was reviewed by Elisabeth Barrington in Space Gamer Number 31 (September, 1980), who commented that, “The character generation rules are a little skimpy at times, and some of the numerous tables are difficult to figure out.” before concluding that, “As new RP systems go, this one is above average. Only one book, and it is well-designed. Historical gamers specialising in the classic period, this is for you.” However, Donald Dupont, writing in Different Worlds Issue 11 (Feb/Mar 1981) was far less positive, opening with the comment, “Odysseus is apparently an attempt at a roleplaying system for the Homeric Age of Greece, the Heroic Age of which Homer sings in his epics Iliad and Odyssey. As a mise en scene for the Bronze Age in the Aegean Basin it fails miserably. As a role-playing system it is disorganized, clumsy, and incomplete. The game lacks color, both of the Homeric Age, which it claims in its title, and of the later Classical Age which, in fact, it more closely approximates.” He finished the review by saying that, “Odysseus is a disappointment. The roleplaying world could use a good Heroic Age game system. With a great deal of interpretation and interpolation, Odysseus is perhaps usable by players familiar with role-playing systems, but the confused nature of its rules, and the lack of color in its world hardly make it worthwhile.”

—oOo—

It is debatable whether Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is a roleplaying game, its wargaming origins being so evidently on show, its focus being mainly on combat, and there being very little in terms of character to either roleplay or develop. This is not to say that the game cannot be played as either a wargame or a roleplaying game, but it would require a great deal of input from both player and Moderator—especially the Moderator, and whatever roleplaying experience might ensue, would definitely come from their efforts rather than be supported by the game itself. Of course, there are many roleplaying games like this, and this is with the benefit of hindsight, but even then, there really is very little to recommend Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age. It simply does not have the right sort of rules to be a roleplaying game and it does not have the background to really do what the author intended. Odysseus – Role Play for the Homeric Age is very much a collector’s curio, a design from the beginning years of the hobby when not every publisher quite knew what a roleplaying game should be or what it should do, a design still influenced too much by the wargaming hobby before it.

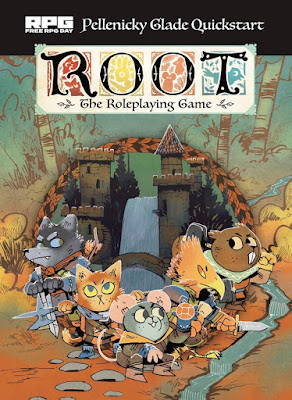

[Free RPG Day 2020] Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, Reviews from R’lyeh has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.Published by Magpie Games, Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is a roleplaying game based on the award-winning Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, about conflict and power, featuring struggles between cats, birds, mice, and more. The Woodland consists of dense forest interspersed by ‘Clearings’ where its many inhabitants—dominated by foxes, mice, rabbits, and birds live, work, and trade from their villages. Birds can also be found spread out in the canopy throughout the forest. Recently, the Woodland was thrown into chaos when the ruling Eyrie Dynasties tore themselves apart in a civil war and left power vacuums throughout the Woodland. With no single governing power, the many Clearings of the Woodland have coped as best they can—or not at all, but many fell under the sway or the occupation of the forces of the Marquise de Cat, leader of an industrious empire from far away. More recently, the civil war between the Eyrie Dynasties has ended and is regroupings its forces to retake its ancestral domains, whilst other denizens of the Woodland, wanting to be free of both the Marquisate and the Eyrie Dynasties, have formed the Woodland Alliance and secretly foment for independence.

Between the Clearings and the Paths which connect them, creatures, individuals, and bands live in the dense, often dangerous forest. Amongst these are the Vagabonds—exiles, outcasts, strangers, oddities, idealists, rebels, criminals, freethinkers. They are hardened to the toughness of life in the forest, but whilst some turn to crime and banditry, others come to Clearings to trade, work, and sometimes take jobs that no other upstanding citizens of any Clearing would do—or have the skill to undertake. Of course, in Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, Vagabonds are the Player Characters.

Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’, the mechanics based on the award-winning post-apocalyptic roleplaying game, Apocalypse World, published by Lumpley Games in 2010. At the heart of these mechanics are Playbooks and their sets of Moves. Now, Playbooks are really Player Characters and their character sheets, and Moves are actions, skills, and knowledges, and every Playbook is a collection of Moves. Some of these Moves are generic in nature, such as ‘Persuade an NPC’ or ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’, and every Player Character or Vagabond can attempt them. Others are particular to a Playbook, for example, ‘Silent Paws’ for a Ranger Vagabond or ‘Arsonist’ for the Scoundrel Vagabond.

To undertake an action or Move in a ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game, a character’s player rolls two six-sided dice and adds the value of an attribute such as Charm, Cunning, Finesse, Luck, or Might, or Reputation, to the result. A full success is achieved on a result of ten or more; a partial success is achieved with a cost, complication, or consequence on a result of seven, eight, or nine; and a failure is scored on a result of six or less. Essentially, this generates results of ‘yes’, ‘yes, but…’ with consequences, and ‘no’. Notably though, the Game Master does not roll in ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying game—or Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game.

So for example, if a Player Character wants to ‘Read a Tense Situation’, his player is rolling to have his character learn the answers to questions such as ‘What’s my best way out/in/through?’, ‘Who or what is the biggest threat?’, ‘Who or what is most vulnerable to me?’, ‘What should I be on the lookout for?’, or ‘Who is in control here?’. To make the Move, the player rolls the dice and his character’s Cunning to the result. On a result of ten or more, the player can ask three of these questions, whilst on a result of seven, eight, or nine, he only gets to ask one.

Moves particular to a Playbook can add to an attribute, such as ‘Master Thief’, which adds one to a character’s Finesse or allow another attribute to be substituted for a particular Move, for example, ‘Threatening Visage’, which enables a Player Character to use his Might instead of Charm when using open threats or naked steel on attempts to ‘Persuade an NPC’. Others are fully detailed Moves, such as ‘Guardian’. When a Player Character wants to defend someone or something from an immediate NPC or environmental threat, his player rolls the character’s Might in a test. The Move gives three possible benefits—‘ Draw the attention of the threat; they focus on you now’, ‘Put the threat in a vulnerable spot; take +1 forward to counterstrike’, and ‘Push the threat back; you and your protected have a chance to manoeuvre or flee’. On a successful roll of ten or more, the character keeps them safe and his player cans elect one of the three benefits’; on a result of seven, eight, or nine, the Player Character is either exposed to the danger or the situation is escalated; and on a roll of six or less, the Player Character suffers the full brunt of the blow intended for his protected, and the threat has the Player Character where it wants him.

The release for Free RPG Day 2020 for Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart. It includes an explanation of the core rules, six pregenerated Player Characters or Vagabonds and their Playbooks, and a complete setting or Clearing for them to explore. From the overview of the game and an explanation of the characters to playing the game and its many Moves, the Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is well-written. It is notable that all of the Vagabonds are essentially roguish in nature, so in addition to the Basic Moves, such as ‘Figure Someone Out’, ‘Persuade an NPC’, ‘Trick an NPC’, ‘Trust Fate’, and ‘Wreck Something’, they can ‘Attempt a Roguish Feat’. This covers Acrobatics, Blindside, Counterfeit, Disable Device, Hide, Pick Lock, Pick Pocket, Sleight of Hand, and Sneak. Each of these requires an associated Feat to attempt, and each of the six pregenerated Vagabonds has one, two, or more of the Feats depending just how roguish they are. Otherwise, a Vagabond’s player rolls the ‘Trust to Fate’ Move.

The six pregenerated Vagabonds include Ellora The Arbiter, a powerful Badger warrior devoted to what she thinks is right and just; Quinn The Ranger, a rugged Wolf denizen who left the Woodland proper to escape the war and their past as an Eyrie soldier; Scratch The Scoundrel, a Cat troublemaker, arsonist, and destroyer; Nimble The Thief, a clever and stealthy Raccoon burglar or pickpocket who is on the run from the law; Keilee The Tinker, a Beaver and technically savvy maker of equipment and machines; and Xander The Vagrant, a wandering rabble-rouser and trickster Opossum who survives on his words. Most of these Vagabonds have links to the given Clearing in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart and all are complete with Natures and Drives, stats, backgrounds, Moves, Feats, and equipment. All a player has to do is decide on a couple of connections and each Playbook is ready to play.

As its title suggests, the given Clearing in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is Pellenicky Glade. Its description comes with an overarching issue and conflicts within the Clearing, important NPCs, places to go, and more. The overarching issue is the independence of the Clearing. The Goshawk have managed to remain neutral in the Eyrie Dynasties civil war and in the face of the advance of Marquisate forces, but the future is uncertain. The Conflicts include the future leadership of the Denizens of Pellenicky Glade, made all the more uncertain by the murder of Alton Goshawk, the Mayor of Pellenicky Glade. There is advice on how these Conflicts might play out if the Vagabonds do not get involved and there are no set solutions to any of the situations. For example, there is no given culprit for the murder of Alton Goshawk, but several solutions are given. Pellenicky Glade is a scenario in the true meaning—a set-up and situation ready for the Vagabonds to enter into and explore, rather than a plot and set of encounters and the like. There is a lot of detail here and playing through the Pellenicky Glade Clearing should provide multiple sessions’ worth of play.

Physically, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is a fantastic looking booklet, done in full colour and printed on heavy paper stock. It is well written and the artwork, taken from or inspired by the Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right board game, is bright and breezy, and really attractive. Even cute. Simply, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is physically the most impressive of all the releases for Free RPG Day 2020.

If there is an issue with Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart it is that it looks busy and it looks complex—something that often besets ‘Powered by the Apocalypse’ roleplaying games. Not only do players need their Vagabond’s Playbooks, but also reference sheets for all of the game’s Basic Moves and Weapon Moves—and that is a lot of information. However, it means that a player has all of the information he needs to play his Vagabond to hand, he does not need to refer to the rules for explanations of the rules or his Vagabond’s Moves. That also means that there is some preparation required to make sure that each player has the lists of Moves his Vagabond needs. Another issue is that the relative complexity and the density of the information in Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart means that it is not a beginner’s game and the Game Master will need a bit of experience to run the Pellenicky Glade and its conflicts.

Ultimately, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart comes with everything necessary to play and keep the attention of a playing group for probably three or four sessions. Although it needs a careful read through and preparation by the Game Master, Root: The Pellenicky Glade Quickstart is a very good introduction to the rules, the setting, and conflicts in Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game—and it looks damned good too.

Grindhouse Sci-Fi Horror

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is many things. It is a lost ship to encounter and salvage and survive—and even steal. It is a means to create the layout of any starship you care to encounter. It is a moon to visit, a hellhole of auto-cannibalism, desperation, and caprinaephilia. It is a list of nightmares. It is a planetcrawl on a dead world including a bunker crawl five levels deep. It is a weird-arse incursion from another place, which might not or not be hell. It is all of these things and then it is one thing—a mini campaign in which the Player Characters, or crew of a starship, find themselves trapped around the dead planet of the title. Desperate to survive, desperate to get out, how far will the crew go in dealing with the degenerate survivors around the dead planet? How far will they go in investigating the dead planet in order to get out?

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is many things. It is a lost ship to encounter and salvage and survive—and even steal. It is a means to create the layout of any starship you care to encounter. It is a moon to visit, a hellhole of auto-cannibalism, desperation, and caprinaephilia. It is a list of nightmares. It is a planetcrawl on a dead world including a bunker crawl five levels deep. It is a weird-arse incursion from another place, which might not or not be hell. It is all of these things and then it is one thing—a mini campaign in which the Player Characters, or crew of a starship, find themselves trapped around the dead planet of the title. Desperate to survive, desperate to get out, how far will the crew go in dealing with the degenerate survivors around the dead planet? How far will they go in investigating the dead planet in order to get out?Published by Tuesday Knight Games, Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is the first supplement for MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game, which does Science Fiction horror and action. The action of Blue-Collar Science Fiction such as Outland, the horror Science Fiction of Alien, and the action and horror Science Fiction of Aliens. It works as both a companion and a campaign for MOTHERSHIP, but also as a source of scenarios for the roleplaying game. This is because it is designed in modular fashion built onto a framework. This framework is simple. The starship crewed by the Player Characters suffers a malfunction and is sucked into a star system at the heart of which is not a sun, but a dead planet upon which stands a Dead Gateway which spews dark, brooding energy from somewhere else into our universe. The crew is unlikely to discover this until later in the campaign, by which time they will have encountered innumerable other horrors and nightmares. With their ship’s jump drive engines malfunctioning and the ship itself damaged, the crew find themselves floating through a ships’ graveyard of derelicts. Could parts be found on these ships? How did they get here—was it just like their own ship? And where are their crews? Close by is a likely ship for exploration and a boarding party.

Beyond the cloud of derelict ships is a moon and this moon is a community of survivors. How this community has survived is horrifying, it having to degenerated into barbarism, to a point of potential collapse. Indeed, the arrival of the Player Characters is likely to drive the factions within the community to act and send it to a tipping point and beyond. Not everyone in the community welcomes their arrival, and even those that do, do so for a variety of reasons. However, in order to interact with the community, the Player Characters are probably going to have to commit a fairly vile act—and do so willingly. This may well be a step too far for some players, though it should be made clear that this act is not sexual in nature and will be by the Player Characters against themselves individually rather than against others. Nevertheless, it does involve a major a major taboo, and whilst that taboo has been presented and explored innumerable times onscreen, it is another matter to be confronted with it in as a personal a fashion as Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game does.

Then at last, there is the Dead Planet itself. This is a mini-hex crawl atop a rocky plateau with multiple locations. Not just the source of the system’s issues, nightmares, and madness, but a swamp, a crashed ship, wrecked buildings, a giant quarry, and more. Most of these locations require relatively little exploration, only the deep bunker of the Red Tower does. Plumbing its depths may not seem the obvious course of action for some players and their characters, but it may contain one means of the Player Characters escaping the hold that the Dead Planet has over everyone. Certainly, the Warden—as the Game Master in Mothership is known—may want to lay the groundwork in terms of clues for the Player Characters to follow in working out how they are going to escape.

Taken all together, these parts constitute the mini-campaign that is Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. Separate these parts and the Warden has extra elements she can use in her own game. So, these include sets of tables for generating derelict ships and mapping them out, jump drive malfunctions, weapon and supply caches, colonists and survivors, luxuries and goods found in a vault, and nightmares. All of these can be used beyond the pages of Dead Planet, but so could the deck plans of the Alexis, an archaeological research vessel, the floor plans of the bunker, and so on. Not too often, and likely not necessarily if Dead Planet has been run.

Physically, Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is like MOTHERSHIP itself, a fantastic exercise in use of space and flavour of writing. However, the cost of this wealth of detail is that text is often crammed onto the pages and can be difficult to read in places. It also needs a slight edit. The maps are also good, though artwork is unlikely to be to everyone’s taste.

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is very good at what it does and it is exactly the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game needed—more of the near future setting, the monsters, and the horror that it hinted at. Dead Planet goes further in presenting a mini-campaign and elements that the Warden can use in her own game, although it is still not what MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game really needs and that is the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror RPG – Warden’s Horror Guide. As a horror scenario, the set-up in Dead Planet is both creepy and nasty, but definitely needs the input of the Warden to bring it out. There is no real advice in Dead Planet for the Warden, and both it and its horror will benefit from being in the hands of an experienced Referee, if not an experienced Warden.

Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is a nasty first expansion for MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game, and that is exactly so delivers on the horror and the genre action first promised in the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game. Ultimately though, the horror in Dead Planet: A violent incursion into the land of the living for the MOTHERSHIP Sci-Fi Horror Roleplaying Game is not for the fainthearted, being a Grindhouse Sci-Fi combination of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Event Horizon.

[Free RPG Day 2020] LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 [https://www.fanboy3.co.uk/] in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.

Now in its thirteenth year, Free RPG Day in 2020, after a little delay due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, took place on Saturday, 25th July. As per usual, it came with an array of new and interesting little releases, which traditionally would have been tasters for forthcoming games to be released at GenCon the following August, but others are support for existing RPGs or pieces of gaming ephemera or a quick-start. Again, global events meant that Gen Con itself was not only delayed, but run as a virtual event, and likewise, global events meant that Reviews from R’lyeh could not gain access to the titles released on the day as no friendly local gaming shop was participating nearby. Fortunately, has been able to gain copies of many of the titles released on the day, and so can review them as is the usual practice. To that end, Reviews from R’lyeh wants to thank both Keith Mageau and David Salisbury of Fan Boy 3 [https://www.fanboy3.co.uk/] in sourcing and providing copies of the Free RPG Day 2020 titles.LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is a little different. Published by 9th Level Games, Level 1 is an annual RPG anthology series of ‘Independent Roleplaying Games’ specifically released for Free RPG Day. LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is a collection of fifteen featuring role-playing games, standalone adventures, two-hundred-word Roleplaying Games, One Page Dungeons, and more! Where the other offerings for Free RPG Day 2020—or any other Free RPG Day—provide one-shot, one use quick-starts or adventures, LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is something that can be dipped into multiple times, in some cases its contents can played once, twice, or more—even in the space of a single evening! The subject matters for these entries ranges from the adult to the weird and back again, but what they have in common is that they are non-commercial in nature and they often tell stories in non-commercial fashion compared to the other offerings for Free RPG Day 2020. The other differences are that Level 1 includes notes on audience—from Kid Friendly to Mature Adults, and tone—from Action and Cozy to Serious and Strange. Many of the games ask questions of the players and possess an internalised nature—more ‘How do I feel?’ than ‘I stride forth and do *this*’, and for some players, this may be uncomfortable or simply too different from traditional roleplaying games. So the anthology includes ‘Be Safe, Have fun’, a set of tools and terms for ensuring that everyone can play within their comfort zone. It is a good essay and useful not just for the fifteen or so games in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020.

The difference in LEVEL 1 - volume 1 2020 is that it carries advertising. This advertising is from its sponsors, but it gives Level 1 an old-style magazine feel.

Level 1 opens with the odd. Kira Magrann’s ‘Moose Trip: a game about moose who eat psychedelic mushrooms’. It turns out that as part of their idyllic life in the human-occupied wilds of Montana, Moose actually eat psychedelic mushrooms to get high. Which is what they do in this game and then they engage in relaxed conversation about how they feel and their emotions. It includes twenty different ‘Mushroom Feelings’ and offers a short but relaxed, reflective game.

Density Media’s ‘A Clan of Two: A two-person storytelling game’ is inspired by Shogun Assassin or Lone Wolf and Cub. Whether as an assassin and his son on the run from the Shogun or a bounty hunter protecting his bounty rather than taking him in—see Midnight Run, one player takes the role of the protagonist, a warrior without peer who will adhere to a code. This might the code of Bushido, code of chivalry, and so on, but he will have broken part of the code and gone on the run. The other player takes the role of both Game Master and seer, that is, the baby of the baby cart assassin or the bounty hunter’s quarry, as well of the world around them. He will both roleplay this character and the world. ‘A Clan of two’ uses a table of descriptors and prompts derived from the I Ching to push the story along and to see how the world reacts to the protagonist’s actions. This gives a nice balance between player agency and setting, the player able to roleplay free of rolling dice, whilst the Game Master can focus on the setting and interpreting the results, but together telling a story.

Designed for one player and no Game Master, ‘Dice Friends’ by Tim Hutchings is a one-page game in which stories are built around dice to represent characters and their lives and adventures. Mechanically very simple, there is no genre or setting to this game and beyond some dice dying and some dice leaving, there is little in the way of prompts in the game. Its brevity means that the players need to have strong buy-in to the game and will need to work hard create the world in which the dice/characters live and leave or live and die. The lack of a hook and the need to build the whole world means that despite it being easy to pick up and play, ‘Dice Friends’ may well be too daunting for some.

‘After Ragnarök’ by Cameron Parkinson and Tyler Omichinski, is a post-life, post-apocalyptic roleplaying game of Viking adventure and legends! The player take the role of the Einherjar, the great heroes destined to feast and drink in Vahalla until Ragnarök. That day has come and gone, and with the Gods dead, the Einherjar remain, but with Valhalla decaying, they decide to set out and adventure for the great drinking halls which are still said to exist. This is a roleplaying game in which the Player Characters start out as great heroes with Legends that they create, but as they face Jotun, the great hounds of Hel, and worse, they will fall in battle. However, when they die, there is a chance that their ‘Legends’ will ‘Fade’ and so lose their legendary capabilities. This is much more of traditional roleplaying game, a heroic game of fighting against the dying of the light—that is, the dying of the Player Characters’ light.

Oat & Noodle’s ‘Sojurn’ is a second one-page game for one player and no Game Master. This idea is that the players are leaving on a journey and take three objects with them, such as a mask, an imp, and a key, and when they return from the journey, something has changed. This is another one-player game in which the player is prompted to tell a story, but with actual prompts and an implicit genre, is much less daunting than the earlier ‘Dice Friends’. ‘Breaking Spirals: A single-player RPG inspired by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance & Commitment Therapy’ by Cameron and Colin Kyle is also for one player and no Game Master, but is more complex in that it presents a reflective, self-help game as a tool for active meditation and perspective. To be honest, it is more exercise than game, for although steps can be taken and there can be a sense of achievement in going through the process, there is no sense of winning in traditional way or of a story told. Not that there necessarily has to be either, but the lack either makes it an exercise rather than something to be played.

‘Bird Trek: A game about raptors in space’ by Maarten Gilberts & Steffie de Vaan is a co-operative game of sentient raptor birds in space who as a flock to steal things, but must make its annual migration from Caldera to Frigia via several moons. Many of these moons are strange and growing stranger every year, making the migration more difficult and increasing the likelihood of the flock’s hunger and exhaustion grow. This is a storytelling game about survival and loss as well as exploration and just as well could have been set between Africa and Europe as it could outer space.

In Graham Gentz’s ‘In the Tank: Roleplaying the life of an Algae Colony in a Tank’, the players take on the role of aspects of algae living in a tank. Individually they control aspects such as width, cell, green, and so on, but together they control it collectively. Their aim is achieve sentience and to avoid death, but from Moment to Moment, they must respond to complications, problems and stimulations from inside the tank and outside the tank—the latter often at the hand of ‘The Dave’. Exactly what ‘The Dave’ is, is up for speculation—tank owner, laboratory technician?—but the Dave Master creates the Complication and the Algae responds to it. Successfully overcome a Complication and the Algae moves closer to sentience, the player with the successful means of overcoming the Complication becoming the new ‘Dave Master’. As a game, ‘In the Tank’ is likely to escalate into sentience and success, or spiral into death and disaster, the point being that either result is acceptable, and it is the story told along the way that matters.