We live in The Extant, an isolated bastion of light and creation. It sits in The Nether, a seemingly endless sea of primal chaos whose ectoplasmic forces known as shadow or umbra constantly washes up and crashes down upon The Extant. A veil known as The Curtain protects us, not just from the ebb and flow of the umbra, but also from what lies in the Echos, the distorted, memory-altered reflections of The Extant which sit on the other side of The Curtain, and then beyond that, the Cosmos, dream worlds and nightmares—if not both. Out in the Echoes live ghost-like ephemera, thoughtforms, and further out reside aberrations with alien minds, and then, visages further out, stranger still, mythical even… And oh so many of them want to play in The Extant.

Unfortunately for mankind The Curtain is imperfect, marked with rifts, fissures, and worse that entities from beyond can slip into our world and infect it. They find victims and servants and masters. Things of nightmare lurk in the alleyways, others manipulate and take advantage of our baser natures, whilst covens and cults make dark pacts for power, influence, and worse. Such things might be ghosts, demons, vampires, doppelgängers, the undead, or they might not, but like monsters under the bed or boogeymen in the closet, they are all real. As the strangeness and the monsters emerge into our world and magic grows, there are those who have reacted to this—investigators, mystics, occultists, hunters, and even monsters, seeking to protect the fragility of our existence. Such persons are cast in two lights—Illuminated and Shadowed. The Illuminated are ordinary persons driven to face the supernatural and do something about it—protect others from it, hide it, or even learn more about it, whilst the Shadowed have been changed by it, and may be a bloodsucker, one of the living dead, a host to an inhuman entity, a warlock, or something else. Whatever it is, it is now part of their nature and as much as they work against the incursions of the supernatural, their unnatural nature means that they will never be truly regarded as heroes.

This is the set-up for

Sigil & Shadow: A Roleplaying Game of Urban Fantasy and Occult Horror, in which myth, magic, and urban legend crash upon a very modern post-truth world. Not our world exactly, but a parallel one. Published by

Osprey Games,

Sigil & Shadow employs the simple percentile mechanics of the

d00Lite System and presents the means to create a range of beings and entities drawn from the horror and urban fantasy genres, a flexible—potentially too flexible—magic system, and solid advice for the Guide—as the Game Master is known, to set up her own campaign typically based on an area she knows or a maps she has adapted.

A Player Character in

Sigil & Shadow is defined by his Casting, Background, Oddity, Ability scores, Skill Trainings, special features—including perks and powers, descriptors. Each Casting represents an archetype and an associated Drive, or motivation,. There are eight Castings, four belonging to The Illuminated and four to The Shadowed. The Illuminated have Drives which push them to interact with the supernatural, whilst The Shadowed are driven by their supernatural, often monstrous natures. The four Castings for The Illuminated are the Seeker, the Hunter, the Protector, and the Keeper, whilst the four Castings for The Shadowed are the Afflicted—inheritors of a cursed bloodline, the Devoted—granted power by a patron, the Host—possessed, willingly or unwillingly, by an Inhabitant, and the Ravenous—which is forced to consume a specific thing in gross quantities. An Oddity might be a Birthright, Altered Reality, Raised in a Cult or as an Experiment, and so on, and not every Player Character has one.

A Player Character has four Abilities rated out of one hundred, Strength, Dexterity, Logic, and Willpower. A Background is a Player Character’s occupation, from Activist, Artist, and Athlete to Techie, Thrill-Seeker, and Wealthy, and determines his Lifestyle and gives his player a choice of three Perk, or advantages, to choose from. For example, the Politician has an Upper Class Lifestyle Rating and offers the Perks of Well-to-Do, and either Skill Training in either Social or Education. Perks can add bonuses to a Player Character’s Abilities, advantage on particular skills, and other benefits. There are ten Skills, each rated between levels zero and five. A Player Character with level zero in a skill is trained in it, but adds +10% for each level above that to a maximum of Level Five and +50%.

If a Player Character is trained in Mysticism, then he also gains a Gift, which starts with Sixth Sense, and with further training can unlock Heal, Mesmerise, Psychometry, or more. A Shadowed Player Character will have a Manifestation, a paranormal ability or boon, such as Animal Companion, Blink, Ethereal Form, Heightened Senses, Inhuman Ability, Terrifying, and more. He will also have a Burden, like a Dreadful Feature or Strange Compulsion, and can have more should a player want his character to have more Manifestations.

To create a character, a player selects a Casting, rolls for a Background, and assigns ten Advancements to his Abilities. These begin at 40% each, and each Advancement adds +5%, to a maximum of 70%. Alternatively, an array is provided. He then effectively selects two skills and sets them at Level 1 (+10%). Lastly he writes two descriptors, one positive, one negative, to flesh out the Player Character, chooses some equipment, and determines secondary factors. Throughout, a player has access to his character's pool of five Bones, which can be permanently expended at certain steps during the Player Character creation process to choose an aspect of the character instead of determining it randomly, to gain extra Perks, and Skill Training.

Our sample Player Character is Heath Carlson, an assistant professor of comparative theology who came into an inheritance from his late uncle—a set of papers and journals that dated back to the eighteenth century. They revealed the occult activities and supernatural links of his ancestors and spoke of someone close to the family that aided them in their doings, an older figure only identified as ‘H’. Ultimately Heath returned to his teaching position in the autumn with only hazy memories of what he had done that summer. In the months since, he has suffered more lapses in memory and found himself associating with others he would ordinarily have avoided. There is a voice in his head whispering ideas and suggestions. He has strange new abilities and people are reacting differently to him…

Name: Heath Carlson

Calling: Shadowed (Host)

Drive: Dominion

Oddity: Ancestral Conduit

Rank: 1

Strength: 45% Dexterity: 50%

Logic: 60% Willpower: 55%

Bone Pile: 4

Hit Points: 22

Initiative: 2 Damage Resistance: 0

SKILLS

Arcana (Untrained—Umbra), Combat (Untrained), Education (Theology) Level 1 (+10%), Investigation (Untrained), Larceny (Untrained), Medicine (Untrained), Mysticism Level 1 (+10%), Social (Untrained), Survival (Untrained), Technical (Untrained)

Background: Scholar

Lifestyle: Middle Class (2)

DESCRIPTORS

Insatiably Curious

Gullible

POWERS

Perk: Encyclopedic Mind

Gift: Sixth Sense

Manifestations: Channel (Arcanum), Terrifying

Burden: Misfortune

NOTES

Heath is Timid, but Kind, whereas ‘H’ is Assertive and Cruel.

EQUIPMENT

Investigator Pack, Occultist Pack, Plain Clothes, Midsize car

The character creation process in

Sigil & Shadow is not difficult, but it does get involved in places, particularly when creating one of The Shadowed. It specifically asks a player to explain how his character came to embrace the change and how it manifests, but what it does not do is give examples or suggestions. This is intentional, since it frees both players and Guide from necessarily adhering to traditional monsters, such as vampires or werewolves or ghosts or… Now there is nothing to stop both players or Guide from creating versions of The Shadowed which would fit into those archetypes, and certainly, the rules would easily support that. Plus there is an option to add Shadowed Origins which do fit into categories such as Undead, Aberrant, Fey, Eldritch, or Engineered. As much as this openness supports player and Guide inventiveness alike, it also means that

Sigil & Shadow lacks off the shelf archetypes that might have eased the creation process.

In terms of its mechanics,

Sigil & Shadow uses the

d00Lite System and is quite light. To have his character undertake an action, a player rolls percentile dice aiming to roll equal to, or under a Success Value. Typically, a Success Value is equal to an Ability plus a Skill—though untrained skills count as a -20% penalty. A roll of 00 to 05 is always a success, whilst a roll of 95 and more is always a failure. A high roll under the Success Value is considered a better result, especially when comparing rolls, and a roll of doubles under the Success Value is a crucial success, whilst a roll of doubles over the Success Value is a crucial failure. If a Player Character has advantage, his player can rearrange the dice roll for his character’s benefit, but the dice roll is rearranged the other way if the Player Character has disadvantage.

Combat is kept similarly short and simple—and potentially deadly. For a horror game,

Sigil & Shadow has no specific systems for handling fear or terror, instead using conditions like Frightened, suffered after a failed Willpower resistance roll when a Player Character is exposed to the unnatural or the supernatural.

In addition, each Player Character has his own personal Bone Pile. The Bones in this pile have a number of uses in

Sigil & Shadow. During character creation, they can be used to improve a character, but this permanently expends them and reduces the size of a Player Character’s Bone Pile in play. During play, they are primarily expended to allow rerolls of failed rolls, to gain Advantage on a roll tied into a character’s positive Descriptor, or to negate Disadvantage triggered by his negative Descriptor. A Bone Pile refreshes at the beginning of a new adventure or scenario, but a player can earn Bones for good roleplaying and for his character adhering to his Drive.

The Illuminated have further uses for Bones that The Shadowed do not. The player of one of The Illuminated can expend a Bone to force the Guide to reroll and use the result which benefits the Player Characters; to let another player reroll a failed roll; automatically succeed at a resistance roll; automatically inflict maximum damage on a successful attack; and guarantee that for one round any action taken by the character—or against him, cannot kill him (though injury may ensure…). Essentially, The Illuminated are lucky where The Shadowed are not.

In addition to The Shadowed, ‘Modern Magic’ plays a major role in

Sigil & Shadow. It has found a greater place in society, openly discussed and dismissed in equal measure, whether at the coffee shop round the corner or the social network of your choice. Learning is a matter of hard work and effort, more so than just belief, whilst casting requires a catalyst—a physical or symbolic offering tied to a spell’s nature to trigger the spell. For example, a Hydromancy spell might require a splash of water. Spells often require a focus, such as a wand or crystal ball, and are fuelled via an invocation or ritual. However, invocations take time. Alternatively, sorcery is a more immediate form of magic, the caster channelling the forces of arcanum through his body, effectively becoming the catalyst, though this is dangerous because it can backfire and there is a karmic backlash as the power for a spell has to come from somewhere. For example, if a sorcerer douses a fire with a sudden downpour, the fire engine sent to fight the fire might suddenly run out of water. Ultimately, practitioners of sorcery may suffer from Sorcerer’s Stain, a sort of karmic mark that identifies the sorcerer to the victims of his magic.

In play, magic in

Sigil & Shadow is intended to be freeform, the player discussing with his Guide the aims of the spell and the Guide setting the Difficulty to apply to the Success Value before rolling. A spell is built from its intended effect, method of delivery, form, and catalyst, and from these the Guide determines whether the spell is Low-, Mid-, or High-Magic. Low-Magic is generally easy, discreet, and quicker to cast, with Mid- and High-Magic growing in complexity, obtrusiveness, and casting time. Magic is broken down into a number of Arcana, each of which is studied separately using the Arcanum skill. The Arcana are divided into the Fundamentals, such as Aero, Aqua, and Umbra, and the Apocrypha, like Musicorum or Techno. Where the Fundamentals cover the traditional Platonic Elements, the Apocrypha are very modern magic—too modern according to some traditionalists. Each Arcana has four aspects and several foci. For example, Aqua’s aspects are water, empathy, illusion, and cleansing, its foci being cups, chalices, bowls, and jars, which covers quite a broad range and gives a Player Character plenty of scope in terms of what he can within an Arcanum.

In addition,

Sigil & Shadow can summon and bind entities for arcane aid; place Sigils which capture and hold magic until the seal is broken, whether on an item, a person, or a place; and create relics and artefacts, though most take the form of consumables charged with spell-like effects, rather than permanent items, which are rare. Now whilst

Sigil & Shadow is not a roleplaying game of modern magic with lists of spells as such, there is a list of sample spells, three per Arcanum. These do help Guide and player alike get a feel for what spells can look like in

Sigil & Shadow, whilst the process is eased with the inclusion of a summary and a cheat-sheet. Both are necessary, because despite its stated aim of spell-casting being easy and freeform, magic in

Sigil & Shadow is not quick in play. Magic is a matter of negotiation and discussion between player and Guide, a player setting out what he wants his character to achieve and the Guide setting the terms. This takes time, especially when first learning to play

Sigil & Shadow, though this is eased by a Player Character typically only knowing the one Arcanum at the start of play. Nevertheless, the need to negotiate and discuss the desired spell effect breaks the flow of the play, as effectively it has to stop to discuss game mechanics. Which is fine for the Guide and the player of the magic-using Player Character, but not necessarily for the other players sitting round the table. Initially at least, it might be an idea for the Guide and player to work through ideas together before start of play as to what the player might want his character to to use his Arcanum for and develop some modifiers and outcomes that will be easier to adjust in play rather working through them on the spot. At least until both Guide and player are at ease with the system.

For the Guide there is a solid cast of antagonists and entities. These are kept nicely simple, just a few lines, including sample Crpytids like Impish Aberrations and Zombies, whilst Strange Encounters provides more detailed creatures, entities, and things, with write-ups more like that of a Player Character. For example, Cadence appears as a sickly old man with pale skin, yellow teeth, uncomfortable grin, and seemingly dead eyes at dance venues, raves, nightclubs, concerts, and the like, encouraging attendees to dance, dance, and dance… Included are several opinions as to what Cadence might be, which nicely add colour to his description, and then the descriptions of each of the other Strange Encounters. Just eight are detailed, but they feel contemporary and very much suit the modern setting of

Sigil & Shadow.

The advice of the Guide covers safety tools, themes, styles, and discussions of what The Illuminated, The Shadowed, and the Cosmology are. The discussions are brief, perhaps too brief, and this is not helped by a lack of a campaign setting or ready-to-play scenario. There is advice for creating, in particular building a campaign around a real-world map and adding descriptors and details, as well as setting up feuding and allied factions, and there is a scenario outline. An appendix provides further suggestions of add to campaign. Overall, the advice is good, but it is underwhelming and ultimately leaves a lot for the Guide to do before being able to bring

Sigil & Shadow to the table. This includes learning the magic system as well as setting up a campaign location and writing a scenario.

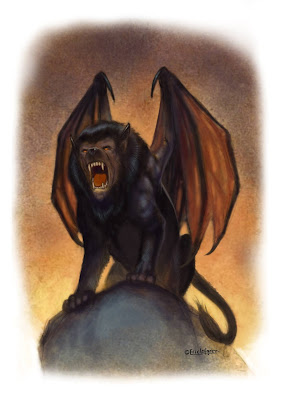

Physically,

Sigil & Shadow is nicely presented as you would expect for a book from Osprey Games. The artwork is excellent, though it does need another edit, and in comparison to other titles from this publisher, it is not as dense, making it an easier, more accessible book to read. It could perhaps have done with some more detailed examples of play and even some sample Player Characters to further enhance that accessibility.

As its title suggests,

Sigil & Shadow: A Roleplaying Game of Urban Fantasy and Occult Horror is a much darker take upon the Urban Fantasy genre and provides the means to explore from the angles of protecting against that horror, exploring it, or even embracing it, depending upon what character types the players create and the campaign the Guide wants to create and run. And it is very much a matter of ‘creating’ and running, as the Guide will need to create her campaign or adapt a setting or scenario to run

Sigil & Shadow. And this adds to the work of the system, if not the complexity, which despite the simplicity of the mechanics, still leaves

Sigil & Shadow with a magic system that equally requires work in play.

Overall,

Sigil & Shadow: A Roleplaying Game of Urban Fantasy and Occult Horror is a solid combination of simple rules and conceptual complexities that needs effort upon the part of both players and Guide to set up and run. For the gaming group looking for a toolkit to run a darker, urban fantasy campaign,

Sigil & Shadow: A Roleplaying Game of Urban Fantasy and Occult Horror is a solid choice.