Magazine Madness 5: Tabletops and Tentacles #1

The gaming magazine is dead. After all, when was the last time that you were able to purchase a gaming magazine at your nearest newsagent? Games Workshop’s White Dwarf is of course the exception, but it has been over a decade since Dragon appeared in print. However, in more recent times, the hobby has found other means to bring the magazine format to the market. Digitally, of course, but publishers have also created their own in-house titles and sold them direct or through distribution. Another vehicle has been Kickststarter.com, which has allowed amateurs to write, create, fund, and publish titles of their own, much like the fanzines of Kickstarter’s ZineQuest. The resulting titles are not fanzines though, being longer, tackling broader subject matters, and more professional in terms of their layout and design.

—oOo— Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition sets out to bring you a variety of content. Published by Deeply Dapper Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it promises to give the reader a variety of content, including reviews, RPG adventures, columns, dice tables, world building, interviews, original art, and more—and it certainly lives up to that. However, from the outset, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 looks to be and promises to be a gaming magazine, with its title of ‘Tabletops & Tentacles’ and the cover reading, “The monthly magazine of RPGs, Tabletop Games, Comic Conventions, Art Reviews, Adventures & More! In this prodigious premiere issue, you will find adventure hooks for roleplaying games, RPG dice tables, reviews, artist and game designer interviews, original art, tips, tricks, NPCs, treasure and maps.” Which is a lot, and makes it sound like a gaming magazine, which it is not, because the focus of the magazine and the issue is much broader than gaming, very much on the ‘more’, so it is less like Dragon or Dungeon magazine, and more like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and SFX—all of which inspired the editor and publisher—with some gaming. Thus the reader should not go into it expecting a lot of gaming content or indeed to get anything in the way of gaming content until quite a few pages in. However, this does not mean that the non-gaming content is not interesting, but since it was published in 2020, some content will have something of a retrospective quality (but to be fair, that is exacerbated by this late review) and much of it has a very American focus.

Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition sets out to bring you a variety of content. Published by Deeply Dapper Games following a successful Kickstarter campaign, it promises to give the reader a variety of content, including reviews, RPG adventures, columns, dice tables, world building, interviews, original art, and more—and it certainly lives up to that. However, from the outset, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 looks to be and promises to be a gaming magazine, with its title of ‘Tabletops & Tentacles’ and the cover reading, “The monthly magazine of RPGs, Tabletop Games, Comic Conventions, Art Reviews, Adventures & More! In this prodigious premiere issue, you will find adventure hooks for roleplaying games, RPG dice tables, reviews, artist and game designer interviews, original art, tips, tricks, NPCs, treasure and maps.” Which is a lot, and makes it sound like a gaming magazine, which it is not, because the focus of the magazine and the issue is much broader than gaming, very much on the ‘more’, so it is less like Dragon or Dungeon magazine, and more like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and SFX—all of which inspired the editor and publisher—with some gaming. Thus the reader should not go into it expecting a lot of gaming content or indeed to get anything in the way of gaming content until quite a few pages in. However, this does not mean that the non-gaming content is not interesting, but since it was published in 2020, some content will have something of a retrospective quality (but to be fair, that is exacerbated by this late review) and much of it has a very American focus.After the editorial in which editor Kris McClanahan, sets out his stall—far better than the cover to be fair—Tabletops and Tentacles #1 provides a previews of a few then-forthcoming tabletop games, which would have very rapidly out of date anyway, and with that hindsight, is really of interest to see what happened to them. It is followed by a preview of the LEGO Haunted House, which feels less of a preview and more of an advert. The first real article is a travelogue, an entry in the regular ‘Tales from the Cthulhu-Haul’, this time around, ‘Tales from the Cthulhu-Haul: Keep Portland Weird’. Written by the editor, it describes a visit to the city and some of its weirder corners, including a tiki bar and curiosity shops. The travelogue has a certain colour to it, but looking back from 2021, it feels weird even to be going out and visiting places like this, so there is an even stronger sense of the other to the piece. Kris McClanahan also contributes two Star Wars-related articles to the magazine. In the regular column, ‘The Binge’ he rewatches the Star Wars Saga via The Machete Order and records his thoughts, and the response is far more entertaining than his other Star Wars article in ‘The Top Ten’ column, ‘The Top Ten: Star Wars Aliens’, which is just an uninspiring list.

In fact, editor Kris McClanahan writes several columns in Tabletops and Tentacles #1. ‘Tales from the Cthulhu-Haul’ and ‘The Top Ten’ are followed by ‘50 Films You DON’T Need To See’, with its first entry being ‘50 Films You DON’T Need To See: Toy Story’. Given more of a focus than the earlier columns, this is an enjoyable appreciation of the film, warts and all. He provides a not dissimilar treatment of H.P. Lovecraft’s The Dunwich Horror, which breaks down its plot, history, what he liked and disliked, along with his final thoughts, trivia, and more, and again is an enjoyable appreciation.

‘Quarter Ben’—probably written by Ben Cowell, but is not clear—expounds upon the writer’s love of the bargain bin in his childhood with ‘Quarter Ben: Hawkeye’ and a particular mini-series starring the Marvel character, Hawkeye. It is very much a nostalgia piece and a personal piece, so there is a degree of separation there between reader and writer. The identity of the author of ‘The Contrarian’ column is kept deliberately secret, but it is barely worth owning up to as said author tells why he has not seen Tiger King—and?

Kris McClanahan also writes almost all of the entries in the Reviews section, the various board games, odd RPG, books, and various television series all given thumbnail treatments bar the first series of Locke & Key, so readers wanting more depth will want to look elsewhere. The other contributor to the Reviews is Lindsay Graves-McClanahan, who also has her own column in ‘This Geek In History’, a timeline of something interesting, in this case, ‘This Geek In History: The Magazine’, which provides a thumbnail history of the printing and the magazine from the invention of the printing press in 1440 through to the last print issue of Dragon magazine in 2013 and the publication of Tabletops and Tentacles #1 in 2020. It is actually quite interesting as a bit of trivia.

Two pieces of fiction appear in Tabletops and Tentacles #1, both presented in two parts. The first is ‘Sowing Dragon Teeth’ by James Alderdice and the second, ‘Dice Eyes at the Palace of Midnight’ by Aidan Doyle. Both are enjoyable, the first is a fantasy story with pulpy tones, the second a Cyberpunk-style tale set in the remnants of a sunset online game, and there is potential for both to inspire a Game Master in developing more from their settings. Hopefully, future issues of the magazine will give scope to develop either story and then lend themselves to further inspiration?

Interviews in Tabletops and Tentacles #1 cover a range of fields of endeavour. These include comics with an interview with T.J. Daman, creator of the indie noir comic series, ENIGMA; graphic design in ‘Graphic Content’, with John J. Hill; and playing boardgames with the members of the podcast, Meeple Nation. Welcome to Artist Alley not only provides a monthly spotlight on artists and creators, it also serves as a series of mini-interviews with each of the subjects and points to the core concept behind Tabletops and Tentacles #1, that it provides a similar experience to attending a gaming convention. Which in this case, of course, includes visiting the artists’ sections. Overall, the interviews are perhaps the lengthier pieces in the issue and informative enough.

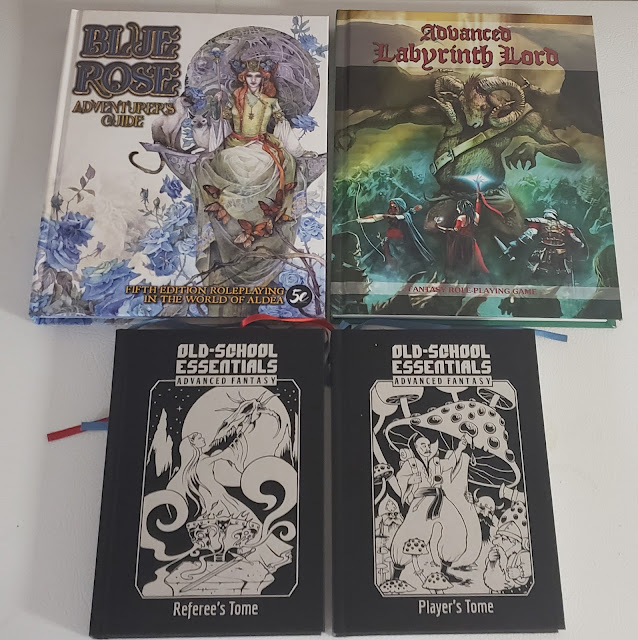

The first real nod to gaming content in Tabletops and Tentacles #1 is Devon Marcel’s ‘Neon Futures: The Road to Cyberpunk 2077’. Written before the release of the controversial roleplaying game, this charts the rise of the cyberpunk, first as a literary genre, and then out into other media—music, television, roleplaying games—Cyberpunk 2013 and Shadowrun in particular, but especially computer games. It is a good overview of the genre, ripe for further exploration in any one of the directions it covers. Introductions to gaming are provided first by Kristopher McClanahan and then Alan Bahr. Kristopher McClanahan suggests a number of gateway board games in ‘The Reformed Grognard: Gateway Board Games’, games suitable for those looking to get into board games, whilst with ‘Tiny Thoughts: OSR and Indie Roleplaying Games’, Alan Bahr suggests points of entry for the Old School Renaissance. His five suggestions in the opening entry for his column stray far from the Old School Renaissance, or at least from the classic retroclones based on Dungeons & Dragons. This makes them more interesting than they otherwise might have been, and perhaps more space might be given for the games themselves.

However, the actual gaming content does not appear until almost one hundred pages into the issue (that is, one hundred out of one-hundred-and-forty pages…). They begin with Kristopher McClanahan’s ‘Blackspittle’s Horde Fantasy Adventure’, a systemless scenario intended for fantasy games like Dungeons & Dragons, Fifth Edition. It is a classic ‘village-in-peril’ set-up coloured by the sap taken from the nearby forest which is put to a number of interesting uses. It is serviceable enough. More enjoyable is ‘Realm of the Moon Ghouls Part 1: The Starship Poe’, also by Kristopher McClanahan, again systemless, but definitely for Pulp Sci-Fi roleplaying games with a tinge of horror, particularly, Lovecraftian horror. The first part of a series which details the universe beyond the walls of the starship Poe, this is enjoyable for what it is as much as what the rest of the series promises. Hopefully, further issues will live up to the pulpy Sci-Fi promised in this issue.

‘H’AKKENSLASH! An original RPG system’ by Benjamin C. Bailey is the start of a roleplaying game which presumably will be detailed further in future issues. An experienced Game Master and her players will have no issue grasping how this works—essentially the difficulty of a task is measured by die type, a Player Character needing to succeed rolling an appropriate skill, again rated by die type, and attempting to beat the difficulty rolled by the Game Master. This is not clearly explained though, and a less experienced player or Game Master will probably need some help with this. It could have done with fewer magical items and more explanation.

Gaming dice tables include ‘In the Inn’ by Kristopher McClanahan and Lindsay McClanahan, which gives twenty things to be found in the draws of your room at an inn, and Lindsay McClanahan’s ‘The Cave’ gives six adventure seeds leading into, or deeper into, a cave. The latter tend to be more interesting than the former, but there is a decent amount of inspiration to be found here. Lastly, another column, ‘Merchants of the Realm’ begins with ‘Merchants of the Realm: Crag’s Reliable Adventuring Gear’ by Lindsay McClanahan, a likeable description of a travelling salesman and his packed bison caravan, accompanied by some fun gewgaw and doodads.

Physically, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 is generally well-presented, being bright and cheerful. In places, the editing could have been stronger, but hopefully that will get better with future issues. The nature of the layout and the relative shortness of many of the articles means that it looks busy in places though.

The initial reaction to Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition is one of disappointment, because it is not a gaming magazine as the cover, or even the title, suggests—the ‘more’ mentioned on the cover making up the bulk of the issue. Yet get past that, and Tabletops and Tentacles #1 actually turns out to be a readable magazine dedicated to fandom in general. It covers a breadth of subjects, not always in any depth, but many of the articles are interesting and informative, even entertaining. Others though, are fluff and filler, even hard work. As to the gaming content, much of it is decent enough, but really needs development—to one degree or another—by the Game Master to be of use.

If you are looking for a gaming magazine, then there really is not sufficient gaming in its pages to recommend Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition. If you are looking for a general fandom magazine with some gaming content that can you work with and develop, Tabletops and Tentacles #1 – The Kickstarter Edition is serviceable enough. Hopefully, it will get better and more substantial in future issues.

—oOo—

A Kickstarter for Tabletops and Tentacles Magazine #3: The Cryptid Issue ends on Wednesday, July 14th, 2021